The Organisational Transformation of the US Army: The Next Six Years

* This article is based on an edited transcript of a presentation delivered by the author to the Australian Chief of Army’s Exercise in Canberra in October 2004.

The next six years are likely to be extremely difficult for the US Army both operationally and on the organisational front. This article will concentrate on the organisational changes that the Army is attempting to make in order to meet its many operational commitments. It is important to understand the challenges of the environment that the US Army faces, not only from an external standpoint, but also from an internal point of view. The article concentrates on trying to explain why the US Army has had to rethink its philosophy of transformation and then outlines how the process of transformation might occur. Since it is not possible to discuss these aspects without some consideration of their context, this article begins with an analysis of the rationale behind change.

Why the US Army must change

In the present war in Iraq there is no uniformed, or uniform, opponent. Iraq represents not just the Three Block War; it is the Three Block War under a microscope. Everything that the US Army does on the ground takes place in an atmosphere of accountability in which every individual action, from the level of a private soldier to that of a high ranking officer, is open to scrutiny by higher authority. Under these conditions of heightened scrutiny, some individuals have become infamous, with Private Lynndie England of Abu Ghraib being perhaps the most well known. There are no heroes in the war in Iraq. Indeed, it is not possible to name one private soldier that has performed a heroic act in this war, at least not in the US Army. While many American people believe that they are at war intellectually, they are certainly not aware of the fighting on an emotional level. Those of us in the Army mourn our losses, but with the realisation that many of our fellow citizens probably do not feel our sorrow. Such a gulf between soldier and nation creates a danger that the US Army may become increasingly isolated from the wider society from which it springs and whose safety military professionals are sworn to uphold.

Operational Tempo and Military Personnel

While the US Army is faced with many challenges, perhaps the greatest challenge that it confronts at the moment is that its combat forces are overcommitted in the field. Currently, the US Army has 350 000 soldiers deployed around the world. One quarter of its Reserve Forces, both National Guard and Army Reserve, have been called up for active duty at sometime since 2001. The present high level of deployment shows little sign of diminishing. Of the Army’s thirty-three brigade-sized force, between seventeen and eighteen brigades are required for the Afghanistan and Iraq theatres. Based on deployment requirements soldiers know that they are going to be at war about every two years or on an almost continuous series of deployments with a rotation pattern of 1:1. However, there are other contingencies outside the current war in Iraq—contingencies that require a military reserve of approximately four or five brigades. As a result, the US Army will soon reach a point where its soldiers are almost continuously deployed.

A recent study of military personnel found that somewhere around 47 per cent of soldiers are the sons and daughters or brothers and sisters of soldiers. As a self-perpetuating group, professional soldiers are being drawn from an increasingly narrow part of American society. The risk is that the commitment of military personnel to uniformed service will become a personal affair rather than an issue of public awareness. At the same time, as noted above, the Army’s reserve component has also been heavily committed to operational duty. Indeed, the volunteer US Army has now reached a situation where, if it continues to operate as it has in the past, its personnel will ‘burn out’ very quickly.

In the late 1990s, 60 per cent of the Army’s personnel were married. Today, that figure is less than 50 per cent. The reason for this decline is not necessarily that of divorce and separation; it is simply that soldiers do not stay in any one place long enough to form relationships that can lead to the status of marriage. What such statistics mean is that the US Army’s operational tempo is determining the lifestyle of its soldiers. In the long term, the sheer pressure that contemporary military service produces on the personal lives of soldiers and officers will lead to military personnel making decisions about quality of lifestyle that are likely to be detrimental to both the Army’s retention system and its recruitment base. In order to avoid these problems in the future, the Army must change its personnel practices.

Rethinking Military Transformation

When General Peter Schoomaker became US Army Chief of Staff, he examined the concept of military transformation and decided that it had to change. In the late 1990s, under General Eric Shinseki, the Army had come up with a concept for transformation that was lovingly called ‘The Big Bang Theory’. Essentially, the Shinseki theory of transformation was based on the premise that the global strategic environment would change gradually rather than rapidly. This model of gradualism allowed the military to take advantage of a strategic window of opportunity in which it was believed that it was unlikely that the United States would have a peer, or even near-peer, competitor for the foreseeable future. In addition, by around 2010 or 2012, the process of transformation would begin to deliver a great number of new military capabilities. Indeed, the Army concentrated on investing US $1.4 billion a year on science and technology and research and development that, with a very few exceptions, did not change the lives of American soldiers.

Military Change and Organisational Culture

General Schoomaker’s new assessment is that the strategic window of opportunity of the 1990s has now closed simply because the world of the early 21st century has changed fundamentally. The Chief of Staff now believes that the new model for transformation is one in which the Army will move from the present to the future but never achieve the future force that was its goal in ‘The Big Bang Theory’. Instead, the US military will now focus on those ideas and technologies that have the potential to save soldiers’ lives in contemporary operations. While there is a degree of uncertainty about the way in which the US Army’s future plans will be executed, it is important to understand that changes will happen quickly. The current plan for change will focus on four main points. The first and most pressing need is for the Army leadership to try to stabilise the current land force. Second and third, once this stabilisation has been achieved, the force will be rebalanced and made more modular in structure. Finally, while stabilisation and restructuring occurs, it will be important for the Army to maintain the warrior ethos and martial spirit in its personnel. All four of the above changes are closely interrelated, and all of them present military leaders with the challenge of maintaining the best features of the US Army’s organisational culture.

Military culture is, of course, a strange phenomenon. The author’s father was a soldier. Just before the writer’s commissioning he said, ‘You know, it’s very important that you get engraved name cards and that you understand that if you visit an officer’s house, there will be a silver dish next to his door. If you go by yourself, you must fold over one edge of the card’. In the author’s service he has never been to an officer’s house where there was a silver tray by the door. The author’s son is also an officer and has even less idea about the cultural relevance of name cards and silver trays. The point that must be grasped by observers is that aspects of the US Army’s culture have changed from generation to generation. The challenge of change is to maintain a balance between what features can be discarded and those vital aspects of organisational culture that must be preserved.

In the US Army, it is normal for a soldier to undertake a three-year tour of duty in a posting. Such a career pattern has had the benefit of making the Army a homogeneous force with wide experience. For example, the author has served in seven different regions of the United States, spent twelve years in Germany, and has served in South Korea. However, the drawback of such a career pattern is its impact on non-commissioned officers. For instance, a sergeant in the US Army will go into the operational force and may stay there for his or her whole career. The commitment to service involved is enormous because, at the same time, that sergeant will receive a new posting every three years.

Breaking with the Military Past

In the future, continuous rotation will cease. The goal of the Army leadership is for units to stay in one place and for military personnel to engage in a seven-year appointment. Such a reduction in posting will mean that the Army will need to reconsider what qualities make a good officer or a good non-commissioned officer. In the past, personnel who sought to stay in a single posting for an unusual length of time gained reputations as being ‘homesetters’.

Their punishment came in being overlooked by promotion boards, usually in the form of having their files stapled shut. In the future the US Army will have to move away from that punitive model. The military leadership will have to understand that a new system of longer assignments will help to develop soldiers and officers who gain detailed knowledge of a particular niche of the ground forces, but whose breadth of general experience will differ from that of the past. Another change in the future will involve the way in which military personnel are to be assessed and provided with feedback. In this area, the US Army is moving toward a 360-degree performance-rating process. Beginning with the national training centres, military personnel will write a report about their superiors at the end of a rotation of duty. The 360-degree rating process is already in use for general officers, and it can be a very emotional experience for senior leaders.

New Personnel Processes and Education

In the future, because Army officers will not be moving every three years, they will not receive the full range of developmental experiences that traditionally has equipped them for new environments. Longer postings will present challenges in equipping officers to undertake complex assignments, for example in joint operations. Such problems are not easily solved, but the Army has created a special taskforce that will undertake modelling of new and longer assignment patterns. The US Army believes that, in the future, it will be possible to develop a system of training and education that will produce officers who are competitive for both Army commands and senior joint positions.

In the case of non-commissioned officers, the Army’s intention is to maintain the current system of education. In general terms, when an aspect of knowledge is removed from the current training and education process, it is often replaced by a subject that is likely to make the process more responsive to the needs of the future. For example, the Army will re-examine the role played by knowledge of history in professional military education. This approach is based on recognition by the Army that there has been neglect of one of the great laboratories of the profession of arms.

Unit Stability and Career Patterns

In order to accommodate new changes, the Army will need to institute a number of new processes, beginning with the individual replacement system. Historically, the Army has operated with a system of individual replacements because it did not normally rotate units; it rotated individuals. In fact, the US Army only started tracking people by name after the Korean War of 1950-53. Before the early 1950s, the Army’s personnel method was to assign unnamed soldiers to particular units. When soldiers reported to a company headquarters they were entered on the company roll, thus creating a personnel system. It was a wonderfully inefficient system, and the Army has begun to study alternatives.

For example, the US Army has given some attention to the personnel system of the German Army during World War II. The Germans suffered terrible losses in the Russian campaign of 1941–45. Yet, when the size of the corps sectors is examined, the size of each sector is remarkably constant. In 1944 the German High Command questioned this situation. The High Command discovered that field divisions tended to report back at 30 per cent strength, while fielded corps levels were calculated at 60 per cent of their strength overall. Despite these losses, both divisions and corps on the Eastern Front continued to occupy the same ground. When the Wehrmacht command pursued this issue, it discovered that commanders in the field were giving their diminished formations the same mission once performed at full strength and that most units were performing to a high military standard. The reason for this efficiency, despite disparities in numbers, was human bonding by teamwork. Field veterans on the Eastern Front tended to form close-knit primary groups that were militarily proficient. Even at 30 per cent strength, a German unit often proved as capable of performing a mission as a brand-new formation at 100 per cent strength. In short, despite losses that stability of service brought, an operational success was its own career reward.

Another benefit of unit stability is that such a situation clearly aids the process of building quality performance in an army. In a high-quality, long-service army, it becomes possible to rotate units in the same way it is possible to replace one modular building block with another. As far as recruiting and retention goes, the reality is that soldiers enlist, but families must be re-enlisted. In the future, when stability is restored in the US Army, the overall aim will be to try to re-enlist the soldier’s spouse. The process might operate as follows. A combat unit on a three-year cycle of duty might go through a reconstitution process that lasts about two months. New personnel will be brought in to the unit as some 50 to 70 per cent of personnel rotate to new postings. These moves will occur in sequences that support the training process. Soldiers will enlist for a three-year period, during which time the unit will undergo a process of being stabilised. There will not be a two-year enlistment, while there will be an attempt to avoid any four-year enlistment of personnel.

After a unit is formed, it will be equipped, trained and, most importantly, fashioned as a team. At about the six-month mark, the unit will be declared ready and, for a thirty-month period, while its personnel are at their performance peak, they will be deployed. This new process should provide a unit that is capable of two six-month deployments over a thirty-month period. Of course, such a scenario is based on a relatively light operational tempo. In periods of high operational tempo, the unit may be deployed for a year or even two years. However, the benefit will be that many of the soldiers will have lived in a single area for about seven years. This new career pattern will mean that their families will have some familiarity with their posting environment and they will have been able to develop the community support mechanisms that, in many cases, the families of current Army personnel lack.

The seven-year career pattern will not apply to everyone in the US Army. Some combat units—special operations forces, for example—will not be able to work in such a way largely because there simply are not enough personnel for the longer process to work. Similarly, the Army’s logistics forces are not established on a one-for-one basis. Such a process would be inefficient because one logistics unit can usually support several line formations. The logisticians cannot have the same personnel cycle as the line units. Instead, they will have a yearly cycle in which they will go through a sustainment period of about one or two months. During that time, the logistics units will be allocated their new personnel and, after equipment and training, it will be some ten months before they are ready for deployment. The deployment period for these units will be about six months, depending on the nature of the operation. Another group in the Army that will need to be treated differently has been designated as high-demand, low-density (HDLD) units or personnel. These are units such as Civil Affairs or Psychological Operations and skilled individuals such as interpreters. About 85 per cent of these HDLD units and personnel are in the Reserves, and about 70 per cent of them have been mobilised four times in the past seven years. The idea of Reserve Forces is that they are not mobilised with any great frequency. However, the Army has been forced to violate that rule due to its all-volunteer post-Vietnam restructuring which, for reasons that made sound political sense at the time, saw many HDLD category units placed in the Reserves.

Breaking with the Past: New Organisational Structures

The restructuring of the US Army will involve changing the work of 100 000 personnel. Many of those 100 000 people are in the Reserves and, during the restructuring process, some Reserve units will have to change into Regular units and vice versa. As General Shinseki once said, ‘when you go through a transformation, some things are actually going to change’—and change hurts people. As an old cavalryman, the author knows that God’s chosen soldiers are going to suffer hurt. However, the Army has to make changes because it needs to be able to meet the demands of today—and those of tomorrow—with the force that it has.

The American Theory of War and Military Organisation

In order to understand how the US Army will change, it is necessary to understand what the ground force looks like today. The current organisation (Figure 1) flows from soldier to army level. In the American theory of warfare the divisional level was, to borrow a grammatical term, parse the battlefield. The operational employment of forces starts at the upper end of the divisional fight, where ground forces begin to move into joint operations. At the corps level, ground units move from the operational level to the joint campaign plan. Below divisional level the fight was viewed as being at the tactical level of war. This theory of warfare and its hierarchical organisation gave the US Army a neat hierarchy of threes, beginning with the basic formation of the squad. Three squads make a platoon with each successive formation consisting of three sub-units in order to form a company, a battalion, a brigade and finally a division. There were some exceptions in which the Army fielded four platoons in a company and two or four brigades in a division, but generally the combat organisation was based on a hierarchy of threes, and it has proven to be a workable arrangement.

Figure 1. US Army Fighting Forces Today

However, a tripartite combat organisation is also a highly expensive arrangement of forces. For example, in a typical infantry division deployed to South Korea, one quarter of the 16 000 involved soldiers would have the status of a maintained Military Occupational Specialisation (MOS). If all the soldiers with an MOS that related to command and control were removed, another 3000 personnel would be involved. Stripping away the support functions, the personnel in the division are finally reduced to the infantry, who number about a third of the formations strength. This ratio of ‘teeth to tail’ in a large combat formation is an imbalance that the US Army must redress. At the heart of the problem is the methodology involved in employing ground divisions. As General Schoomaker has put it, ‘it’s like buying candy bars with a hundred dollar bill. You can’t get any change’. The US Army’s employment of a division was similar to the hundred dollar bill because, regardless of the scale of the operation and, even if only a small part of the division were employed, the whole formation would be incapacitated. General Colin Powell once said, ‘the night before every fight, I completely reorganised’. In that sense the US Army could get ‘no change’, no resilience, no campaign quality from its divisional structure.

Towards a Modular Force

At this point, it is necessary to consider the concept of modularity. The theory behind modularity is that a military organisation can build a set of units that look remarkably alike. General Schoomaker has directed the US Army to devise a division-level structure in which there are elements of the division whose MOS personnel perform combat duties while other elements are designed to provide the service and support capability required to conduct a military campaign. With such a structure, it will be possible to use a brigade from the 4th Infantry Division, and regiments from the 3rd Cavalry and the 101st Brigade respectively. Each formation might leave the United States from different airports but once united on the ground they would be capable of working together as an efficient amalgam. Unlike the current divisional structure, a modular approach will allow US ground forces to take part in a division and put it into combat without debilitating its chain of command. In the future, it will not be necessary for the Army to deploy the whole division in order to field the capabilities that are required for operations. Instead of following the historic American tradition of sending large, composite formations off to war, the Army will develop the capacity to employ smaller, tailored forces. In turn, these smaller units simplify logistical challenges while creating a larger pool of units that rotate into operations.

Critics of modularity argue that the division is a well-tested formation that goes back to the Napoleonic era. However, when an Army is searching for a new approach to warfare, it cannot become too bound up in military tradition. As part of modularity, the Army has deliberately distanced itself from traditional structures and terminology in order to ensure that the process has some intellectual rigour. Instead of the basic element of the new organisational system being called a brigade, it was initially referred to as a Unit of Action (UA). Other formations received different names as well. For example, divisions and corps were designated as Unit of Employment X (UEX) and Unit of Employment Y (UEY) respectively. The X and Y label indicates the size of the operational formation and its commitment. In late September 2004, the US Army made the decision to call these UA modular units Brigade Combat Teams (BCT). Yet, ultimately, whether the new modular formation is called a brigade or a UA is not the point of restructuring. What matters in restructuring units is that the UA, like the brigade, is still commanded by a colonel and still has a brigade-like structure, but its essential elements have a much more combined-arms flavour alongside the resources necessary to sustain itself in battle.

Currently, one of the major challenges that the US Army faces is the reality that half of America’s ground forces are committed to operations. Yet, the Army is simply not large enough to sustain such an operational tempo. If American ground forces are to continue operating at the present tempo, there will be a need for more brigades. However, recruiting another 10 000 military personnel will cost US $1.2 billion per year. Given such a financial cost, the Army cannot afford to increase markedly in size. As a result, the need is to find a way to create more brigades from the number of troops currently in service. Between 2004 and 2010, the US Army will seek to create a schedule that will add a fourth brigade to every single division. In the case of some formations, this process will mean adding two brigades to bring certain divisions up to a four-brigade strength. Eventually all American ground divisions will be similar in terms of their density of units.

Army Reserve and National Guard forces are likely to present another organisational challenge to change because, in many cases, these units have long been under-resourced. Currently, there are about three Reserve component brigades deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Army will continue to employ its reserve component while bringing reserve units up to the same state of modularity as the regular forces. In this manner it will be possible to add ten or eleven brigades to the Army’s entire strength up until 2010. Such a transformation will be carried out while operational commitments are maintained. The likely result will be a US Army that consists of both Active and Reserve components, and one that fields eighty-two brigades.

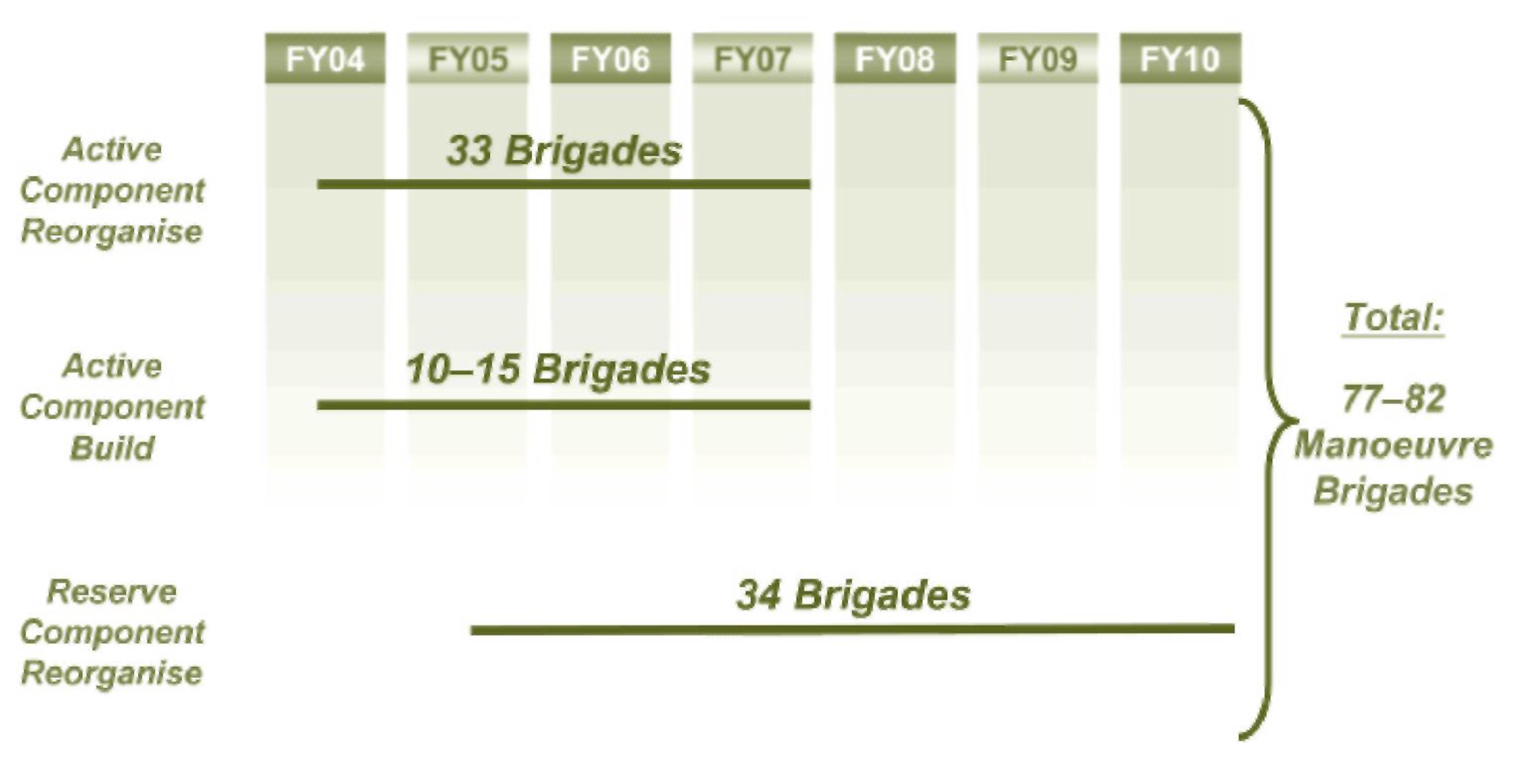

Figure 2 shows the schedule for this process of reorganisation. Formations such as the 10th Mountain Division will be assigned two additional brigades, because in the past it only had two.

The aim of American military reorganisation is to obtain greater density and create a deeper rotation pool in order to sustain the current war and meet the United States’ worldwide commitments. During the reorganisation process, the US Army will convert thirty-three brigades to a modular structure, thus generating about ten additional active-component brigades from within the current force’s strength. Formations such as the 3rd Infantry Division and 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) are at the cutting edge of this process of organisational change. At the same time the National Guard divisions will be similarly converted. By Financial Year 2010-11, it is expected that the US Army of the early 21st century will be a completely modularised force.

From the current structure of divisions, corps and armies, the US Army will move to UA, UEX and UEY designations. While the brigade unit of action will still fight battles and engagements, it will also take some of the functions that, classically, have been assigned to a division. The Army also plans to possess the capacity to employ a brigade unit of action independently in certain operational situations.

Figure 2. Common organisational designs for Active and Reserve

A brigade unit of action will not go into battle by itself. However, in cases that require a stability force or military presence, a UA will have the capability to deploy as an entity and perform that type of mission without drawing on the strength of other units.

Other aspects of military activity also require improvement. Joint interoperability is one of these areas. Moreover, the US Army has not adequately focused on combined operations until its most recent deployments, and it is now accepted that such operations require development over the next few years. New organisational arrangements will also mean that the Army command structure will have to be flatter. A brigade unit of action will remain a colonel’s command, but for three years, rather than the traditional two-year period. There will be a military requirement for further training for UA commanders and, with the seven-year assignment pattern, a major will stay in the same posting for three years. To a degree, there will be winners and losers in the command stakes of the new organisational system, and there will be majors and lieutenant colonels that stay in their commands for a much longer period than they do at present. However, the Army’s planners believe that it will be possible to give all officers the necessary skills to become the type of independent brigade commanders that modern military operations require.

Conclusion

This article has outlined some of the major organisational changes that the US Army will undertake until 2010. There is little doubt that this period will be difficult for many military personnel. However, the benefits that the Army will eventually reap from these changes will be significant and will make a difference to American battlefield performance. General Schoomaker has realised that, in the current strategic environment, a ‘Big Bang’ approach to military transformation is no longer feasible. As he put the problem to some of his senior staff, ‘I’m in a war and most of my money is already committed... I can cancel some things and then I’ll have some money, what should I buy?’ The US Army will invest in its people and its structure over the next few years. As the General has repeatedly underlined, it is a process of change that may concern technology, new organisations or new processes, but it is not about these three factors. Rather, the process of change is about soldiers. Soldiers are at the heart of the American Army, and that truth must be grasped as a fundamental parameter in the new process of transformation. All of the US Army’s new developments must be focused on the soldier or else change will fail.