Volume 20 Number 1

Major General Chris Smith DSC, AM, CSC

DEPUTY CHIEF OF ARMY

Last year in his foreword to Volume 19, Number 1 of the Australian Army Journal, Chief of Army Lieutenant General Simon Stuart, AO, DSC called on the Army to ‘adapt to war’s changing character’ and transform for littoral manoeuvre operations by sea, land and air from Australia, with enhanced long-range fires.[1] This edition of the Australian Army Journal responds to this call. It wrestles with new ideas spanning the past, present and future of land warfare, elucidating how they support the Chief’s vision. This edition includes articles, speeches and book reviews covering land warfare, theoretical concepts for how the Army might respond to changes to warfare, and lessons for strategic thinking.

For my introduction, I hope to situate these papers within the context of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR). It is of little utility to repeat here the big-ticket items out of the DSR; they are amply dealt with elsewhere. Rather, the DSR has three important implications for the Army, which I wish to focus on. Firstly, the DSR is the first Australian Government document since the Cold War focused on a specific threat and the prospect of a major war in the region.[2] Secondly, the DSR commends long-range precision strike as both a threat (with Australia now in range of regional capabilities) and an investment priority (required to threaten an adversary in Australia’s northern approaches). This recommendation is an important nod to the creation of strategic depth in an era defined by reduced strategic warning time. Finally, there is the crucial qualifier applied to Australia’s approach to deterrence: denial.

These three elements of the DSR are of great significance for the Army. They imply a focus on land-based long-range precision strike, land-based air and missile defence, manoeuvre through littoral spaces, and critically close combat from or through fortified positions. For the first time since perhaps the 1950s or 1960s the Army is elevated to a strategic peer of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force. Long-range maritime strike through the acquisition of High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) and a suitable anti-ship missile is particularly important because it gives the Army the capability to achieve some degree of sea denial from the land—a point long argued against, and one worth exploring in the context of public commentary about DSR ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, which I expand upon below. Additionally, the Army’s investment in air and missile defence aims to derive success equal to that of the Ukrainian military, which has curtailed Russian air force operations to a marked extent.

The Army now has an explicit role in denying access to places of strategic importance, and forcing an enemy from such places. For the first time since at least the end of the Vietnam War, if not earlier, there are government-endorsed planning scenarios.

Despite these excellent opportunities for the ADF’s land forces, there exist some enduring criticisms of the document as it relates to the Army. The first line of criticism is external, and it relates to the idea of a focused ADF expressed in the DSR. It contends that a future war will be a maritime one, and that investments in capability for land combat are unnecessary and work against the intention of focus. It is a problematic and ultimately reductionist perspective to believe that all Australia’s strategic problems are solvable by having an ADF solely capable of sinking an enemy invasion fleet at sea. It conflates the idea of focus on a threat with focus on one way to deal with that threat. It is an argument that questions the utility of tanks and infantry fighting vehicles for combat.

The other line of criticism, strangely, comes from inside Army. It is more a line of disappointment than of criticism, which dwells too much on the reduction in the infantry fighting vehicles from 450 to 129 as a serious loss. Both lines of criticism or disappointment are flawed—grounded in an oversimplification of the future we are facing, and a selective view of our history.

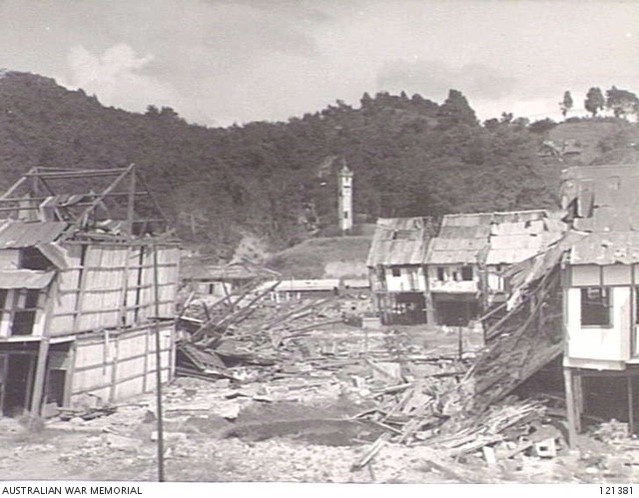

So how do we visualise the role of land forces in an all-domain integrated ADF? The Battle of Milne Bay during the Second World War is a particularly useful example because it represents well what the DSR authors had in mind. Both General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander South West Pacific Area, and the Japanese military recognised, almost at the same time, that the eastern tip of New Guinea was critical for exercising control of the Solomon Sea. Fortunately, MacArthur got Australian troops there first, occupying Milne Bay and commencing construction of three airfields. This led to a defensive battle against a Japanese amphibious force hoping to seize the airfields for their own use.[3] What resulted was a land battle to protect airfields, and the airfields were only important to the extent that they allowed for air power to control a large part of the Solomon Sea—a battle on land for control of the sea.

That is the vision of all-domain warfare: a battle fought in one domain for an effect in another. It is the vision for land power’s integral contribution to an integrated force. It is not new; we’re just going to do it with new stuff. The Battle of Guadalcanal was largely the same but the roles were reversed. In that example, the Japanese defended the airfield (Henderson Field), while US Marines and soldiers fought to capture it and then to hold it against strong Japanese counterattacks.[4] To this end, the focused all-domain ADF needs to be able to both defend and attack, and the land force is essential for both.

Indeed, the Pacific War was essentially a war fought in the littoral for control of airfields. For the Japanese, these airfields served as an essential means of defence, and for the Allies they were a way of extending the reach of bombers to the Japanese mainland. If you extend that idea to the present, imagine that land-based missiles offer an additional means to do what air forces and aircraft carriers did in the Second World War. Imagine that Australian offshore territories and nearby regional neighbours offer adversaries an opportunity to position ballistic missiles in range of Australian cities. And imagine that we would want to pre-empt any such attempt, or have the capacity to forcibly remove such a force. I think that is the best expression of the idea of the all-domain force, coupled of course with the new supporting capabilities of space and cyberspace.

If we are lucky, and if we have sufficient warning of an adversary’s intention to attack, and if we are called upon by a like-minded and concerned regional country, then pre-positioning land-based long-range missile batteries gives the ADF the capacity to exercise limited sea denial from the land. Land-based missiles have enormous advantages over ship-based missiles and even air-launched missiles. The launchers are incredibly difficult to find, and if they are struck, losses are limited to only a few missiles, a single launcher and its crew. Comparatively, the loss of a ship could include the loss of up to 50 launch pods, all the munitions to match, and several hundred crew. Needless to say, this advantage provided to Australia through land-based strike is a reason why the government increased its commitment to acquire HIMARS.

Being the first to realise this strategic opportunity is critical. Being on the ground first, however, is not easy, because you can’t be present all of the time at all potentially strategic places; it is prudent to be circumspect about assuming that we would be there first. It is not hard to imagine a fait accompli attack in our region, one that is grounded in surprise and takes advantage of the great strength of modern defence. Recent history gifts us with lessons from the Argentinian occupation of the Falkland Islands in 1982. Other examples include Russia’s occupation of the Donbass and the Crimea in 2014, as well as (to a lesser extent) the Chinese development and occupation of features in the South China Sea.

Those who have read Peter Singer and August Cole’s book Ghost Fleet will be familiar with the idea of using commercial vessels to hide a surprise invasion.[5] The employment of a fait accompli, in most if not all examples, is to occupy territory without (or with limited) resistance, rapidly set up for defence, and then use the great advantages of the modern defence and the likelihood of stalemate as a bargaining chip for political concessions. So, in this conceivable future, we have to be able to fight.

When we imagine fighting in this future context it is close-quarters fighting through fortified positions in difficult terrain, not the kind of manoeuvre seen in North Africa, the Sinai Peninsula, the Russian steppe, or the Kuwaiti and Iraqi deserts. Applying the regional DSR focus, fighting would look closer to that in Buna and Gona in 1943 or Balikpapan in 1945, or even the clearing of the North Vietnamese Army bunkers in South Vietnam. It would comprise tanks, infantry and engineers in intimate cooperation, similar to the type of warfare experienced in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War. If we are not already preparing for this future, and making a shift towards this style of warfare, we must start to do so now.

This perspective is also not without criticism. Dissenters from the close-combat logic often argue that if we succeed in deterrence we don’t have to fight. That statement is true, but deterrence is not bluff. Deterrence can be enacted as a function of threatened punishment (such as nuclear deterrence), or by denial (as discussed earlier and as is the preference articulated by the government). Deterrence by denial is akin to the role of NATO armies in Western Europe during the Cold War, or the South Korean and American armies in response to the threat of invasion by North Korea. Deterrence by denial is the idea that a potential aggressor, on seeing the defensive capability and posture of the defender, questions whether they can actually succeed.

In this sense, denial is identical to defence. It is not bluff or bluster. Rather, it is about actual capacity to defend and win in battle. Deterrence by denial is enacted by maintaining the ability to win the resulting battles if attacked and to defend the objective, thereby denying it to the enemy. If the enemy gets the jump on us, we might have to force it from some decisive terrain. In other words, to deny we must practise and prove that we can defend, and also attack.

The underlying challenge to this hefty, but not lofty, task is being able to defend, let alone attack, across the sea in an austere environment. This challenge is true for all capabilities but most significantly for logistics. To achieve deterrence by denial as a land force we require assurance that we can reach the fight, that we can receive reinforcements of personnel and munitions, that we can store excess supplies, and that we can repel attacks and penetrate enemy positions. Critically, though, we need to be able to answer one fundamental question in undertaking these tasks: how do we do it across the sea?

This edition of the Australian Army Journal begins with contributions to this question. In his paper Shallow Waters and Deep Strikes: Loitering Munitions and the Australian Army’s Littoral Manoeuvre Concept, Ash Zimmerlie asks how the Army might apply emerging technology to enhance how it operates in littorals. He explains how littoral manoeuvre and loitering munitions might ensure the future Army is capable of littoral manoeuvre, joint warfare, and strategic deterrence. John Nash seeks to contribute to this conceptual development through his paper Amphibious Audacity about the use of littoral manoeuvre in Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943. Nash presents lessons for the use of military forces today by exemplifying how ‘proper use of the sea grants options to ground forces … as an operational manoeuvre space to gain advantage over an adversary’. William Westerman also identifies critical capability elements for Army’s employment in the Indo-Pacific in his paper A Unique Tool?: Exploring the Value of Deployed Military Chaplains in Australia’s Region. He contends that the Army’s chaplaincy capability is integral to persistent presence in the region through their ability to build relationships, communicate with local populations and understand cultural nuances. These papers are important contributions to answers about capability investments and the application of land power.

Papers by Hannah Woodford-Smith, Andrew Carr and Albert Palazzo offer theoretical conceptions and assessments on emerging changes to warfare and ways the Army might respond to them. Bridging the gap between capability needs and conceptual thinking, Hannah Woodford-Smith’s paper Defining Land Force Mobilisation considers the DSR requirement for accelerated preparedness. It introduces the concept of ‘force-size effect’ and the capability requirements for generating an expanded force. Carr’s paper Owning Time astutely points out that tempo is about more than just speed. It claims that if tempo is understood based on the characteristics of change, congruence and control, Australia will be better placed to face challenges of strategic competition. In Climate Change and the Future Character of War, Palazzo describes a future in which troops will be required to operate in extreme temperatures, in locations with higher disease risks and at the end of increasingly vulnerable supply lines.

Finally, I commend to you the five book reviews in this edition. They cover several matters in relation to the DSR, and they provide insights into key resources that might foster better thinking and awareness within the Army. Dongkeun Lee’s review of The New Age of Naval Power in the Indo-Pacific, edited by Catherine Grant, Alessio Patalano and James Russell, provides an insight into the ‘five factors of influence’ that make warfare in the maritime Indo-Pacific so complex. These factors include the capacity to control sea lanes, deploy nuclear deterrence at sea, implement the law of the sea advantageously, control marine resources, and exhibit technological innovation.

Jordan Beavis further explores one of the DSR’s key themes in his review of David French’s book Deterrence, Coercion, and Appeasement: British Grand Strategy, 1919–1940.Beavis suggests that French’s dense book is a timely reference on the need for enhancing national strengths and being transparent with the public on the dangers posed by those that seek to upend the international rules-based order. Nick Bosio’s review of the latest edition of The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age highlights the value of the whopping 1,200-page historically grounded account of lessons relevant to contemporary great power competition. He notes that all formation/area libraries should have it available—not as a book to read cover to cover but as one to be perused when seeking inspiration and guidance.

Liam Kane reviews Armies in Retreat: Chaos, Cohesion, and Consequences, edited by Timothy Heck and Walker Mills, commending the book as a reminder to relinquish hubris and always prepare for the worst. He observes that the chapters have diverse historic references, leveraging examples from the Peloponnesian War to the Korean War and beyond, and he contends that the book is an important contribution to literature elucidating the civil–military divide. John Nash reviews a similarly historically literate publication by Lawrence Freedman covering the overlap between the civil and military spheres. Nash highlights two important relationships identified in Command: The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine: the critical and often fraught interaction between military and political leaders, and the need for cooperation between the military and civilians. While not all revelatory, as Nash notes, these lessons are critical to an understanding of our profession of arms.

Similarly, critical to development in light of the DSR are debates generated by key members of our community. Included in this volume are speeches presented by:

- John Blaxland to the Chief of Army Symposium 2023 in Perth on Australian regional engagement

- Nerolie McDonald to the Chief of Army Symposium 2023 in Perth on landing defence partnerships in the Indo-Pacific and beyond

- me to the Synergia Conclave in India on advanced computing and warfare.

This issue of the Australian Army Journal represents points of focus, new thinking and optimism as we implement direction from the DSR. Thank you to the authors for contributing to Army’s body of professional knowledge.

[1] LTGEN Simon Stuart, ‘Foreword’, Australian Army Journal XIX, no. 1 (2023): v.

[2] Commonwealth of Australia, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2023).

[3] See Nicholas Anderson, The Battle of Milne Bay 1942, Australian Army Campaigns Series, no. 24 (Newport: Big Sky Publishing, 2018).

[4] For a narrative of this battle and the broader campaign, see Richard B Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York: Penguin, 1992).

[5] PW Singer and August Cole, Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War (Boston: Eamon Dolan, 2015).

Journal Articles

Speeches

Book Reviews

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Australian Army Journal 2024 Vol XX No.1 (6.28 MB) | 6.28 MB |

Publication Identifiers

ISSN (Print) 1448-2843

ISSN (Digital) 2200-0992

DOI: https://doi.org/10.61451/267506