Non-Linear Manoeuvre - A Paradigm Shift For The Dismounted Combat Platoon

Abstract

The evolving lethality and accuracy of weapon systems in the battlespace should drive dismounted combat platoons to continually modify Tactics, Techniques and Procedures in order to mitigate threats. Implementation of Manoeuvre Support Section down to Company and Platoon level combined with improving communication systems offer new opportunities for dismounted combat platoons to disperse and manoeuvre sub units far more effectively than ever previously seen. This article examines the ways in which dismounted platoon commanders may implement the intent of Army Capability Requirement, Infantry 2012 to achieve success in close combat, utilising the Infantry Battalion Modernisation 2012 model.

Success in Close Combat: Infantry forces will operate in smaller, semi- autonomous teams that adopt swarming tactics. They will be dispersed and ensure survivability by generating a tactical ‘suppression envelope’ of precise fires with enhanced situational awareness and mobility. When required they will concentrate their effects to overwhelm an enemy operating under battle control from an on-scene commander.

- Army Capability Requirement, Infantry 20121

Introduction

he last 50 years have witnessed significant technological advances in the lethality of weapon systems, in communication systems and in situational awareness on the battlefield. Land manoeuvre forces now possess the means to disperse further across the battlefield with commensurate security, yet infantry minor tactics have been slow to adapt and exploit the potential tactical advantages. Rather than exhibiting innovative tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) that complement technological advances and structural reforms within the company and platoon environments, TTPs appear, in fact, to be resisting change.

The recent introduction of manoeuvre support sections (MSS) down to infantry company and platoon level is one case in point. Implementation of the Infantry Battalion Modernisation 2012 (IBM) structure, complete with MSS, has the potential to provide significant additional capability to the modern rifle company. Company commanders are delivered greater organic firepower and options to concentrate three separate MSS into a manoeuvre support platoon (MSP) or detach each to the three rifle platoons. However, these options do not of themselves realise the full potential of IBM 2012. Rather, there needs to be a commensu- rate development of TTPs which exploit the non-linear manoeuvre options now available at platoon level.

Analysis of the platoon TTPs detailed in LWP-CA 3-3-1 Dismounted Minor Tactics (Developing Doctrine) reveals that these are inconsistent with the characteristics of dismounted combat platoons as described in Table 1. Indeed, the TTPs fall short of realising the intent of Army Capability Requirement (ACR) Infantry 2012, specifically concerning the utilisation of small, semi-autonomous teams, swarming tactics, separation of command and control, and robustness. Utilising the MSS capability down to platoon level while still operating with pre-MSS dismounted doctrine will not realise the full potential of the resources and flexibility of command now available to the modern dismounted platoon commander.

Table 1. Characteristics of Dismounted Combat Platoons2

|

Characteristics of dismounted combat platoons according to LWP-CA 3-3-1 |

|

|

1.23 |

Small semi-autonomous teams |

|

1.24 |

Task Organisation |

|

1.25 |

Adaptive Action |

|

1.26 |

Swarming Tactics |

|

1.27 |

Suppression |

|

1.28 |

Separation of Command and Control |

|

1.29 |

Integration of Lethal and Non-Lethal Measures |

|

1.30 |

Application of Fire |

|

1.31 |

Devolved Situational Understanding |

|

1.32 |

Robustness |

|

1.33 |

Close Combat |

The attachment of MSS to a dismounted platoon provides the commander with significantly greater flexibility. Platoon sub-units will be more resilient if the MSS firepower and weight of firepower is maximised to facilitate the freedom of bricks to manoeuvre. Under the IBM 2012 structure, MSS comprises a 12-man section made up of three 4-man manoeuvre support teams (MST). The MST is led by a team leader or commander armed with the standard F88 Austeyr assault rifle. The key firepower within the MST and the platoon as a whole is provided by the Mag58 carried by a gunner. The grenadier carries the grenade launcher attachment and, if deemed appropriate for the mission, will also carry the 84mm Carl Gustav, providing the MST’s explosive capability. The fourth member of the MST is the sharpshooter or ‘squad designated marksman’ to use the terminology favoured by coalition nations. Currently, the MST sharpshooter in Australian infantry battalions carries the Heckler and Koch 417 (HK-417).

These changes to platoon manning have increased the size of a platoon under the IBM structure to some 40 or more personnel. TTPs that restrict the IBM 2012 platoon to operating as a single manoeuvre element in almost all operational environments will not realise the full potential of MSS. Indeed, the signature generated by the size of this single manoeuvre force is so significant that it reduces its ability to remain concealed in order to seek out and close with an enemy element, particularly one with modern intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance capa- bilities. The attachment of MSS down to platoon level provides the modern platoon commander far greater flexibility and this will need to be better reflected in future doctrine and TTPs.

This article will examine how dismounted platoon commanders can utilise the IBM 2012 model to realise the intent of ACR Infantry 2012 to achieve success in close combat. Alternative methods for infantry platoons that seek to operate in non-linear, dispersed, smaller, semi-autonomous teams will also be analysed. Part of this analysis will focus on swarming tactics that generate a tactical suppression envelope which ensures survivability in the future battlespace. The characteristics of dismounted combat platoons as detailed in LWP-CA 3-3-1 will also be examined as part of this analysis.

How Could The Dismounted Combat Platoon Operate Differently?

Increasingly dispersed operations are inevitable — part of a natural battlefield evolution given the growing lethality of modern weapons and improved communi- cation and information systems.3 For this reason, greater dispersion should be a prime consideration for modern dismounted platoon commanders under the IBM 2012 system. The standard MSS deployment by a majority of dismounted platoon commanders involves the callsign and platoon manoeuvring as a complete element. MSS is often broken down into separate MST and attached to another section or patrol as a complete section, located in the vicinity of platoon headquarters (PHQ). Depending on the nature of the terrain, the platoon position can extend anywhere up to 300 metres. This method of deployment is reminiscent of pre-MSS dismounted doctrine, which ignores the full potential of the IBM 2012 model. Current platoon formations incorporating MSS lack responsiveness, flexibility and manoeuvrability. The single platoon entity is predict- able, easy to target and remains conspicuously above the detection threshold. Although this method of patrolling should not be entirely discounted, more variation in the way dismounted platoons operate will be required to more effectively utilise assigned assets.

Swarm Tactics Through Dispersed Patrolling

ACR Infantry 2012 and LWP-CA 3-3-1 describe swarm tactics as highly successful in close combat. Swarm tactics refer to non-linear manoeuvre by several units conducting a convergent attack on a target from multiple axes utilising either long- range or short-range fires coordinated by an on-scene commander.4 Swarming does not necessitate surrounding the enemy; rather, the emphasis is on forces or fires that can strike at will. Examples of swarm tactics abound throughout history in both the natural and human worlds with well-timed, multidirectional assaults from ants, bees and wolf packs to ancient Parthians and medieval Mongols.5 Today’s insurgents use swarming as a form of asymmetric warfare against superior conventional armies from the mountains of Afghanistan to the cities of Iraq with varying degrees of success.6 Swarming in force or by fire has often proven a very effective way of fighting, but it is only now that it is evolving as a doctrine in its own right. This is because swarming largely depends on the devolution of authority to small units and an ability to interconnect those units, something that has only recently become feasible with the improved firepower and developing communications systems of the IBM 2012 model.7

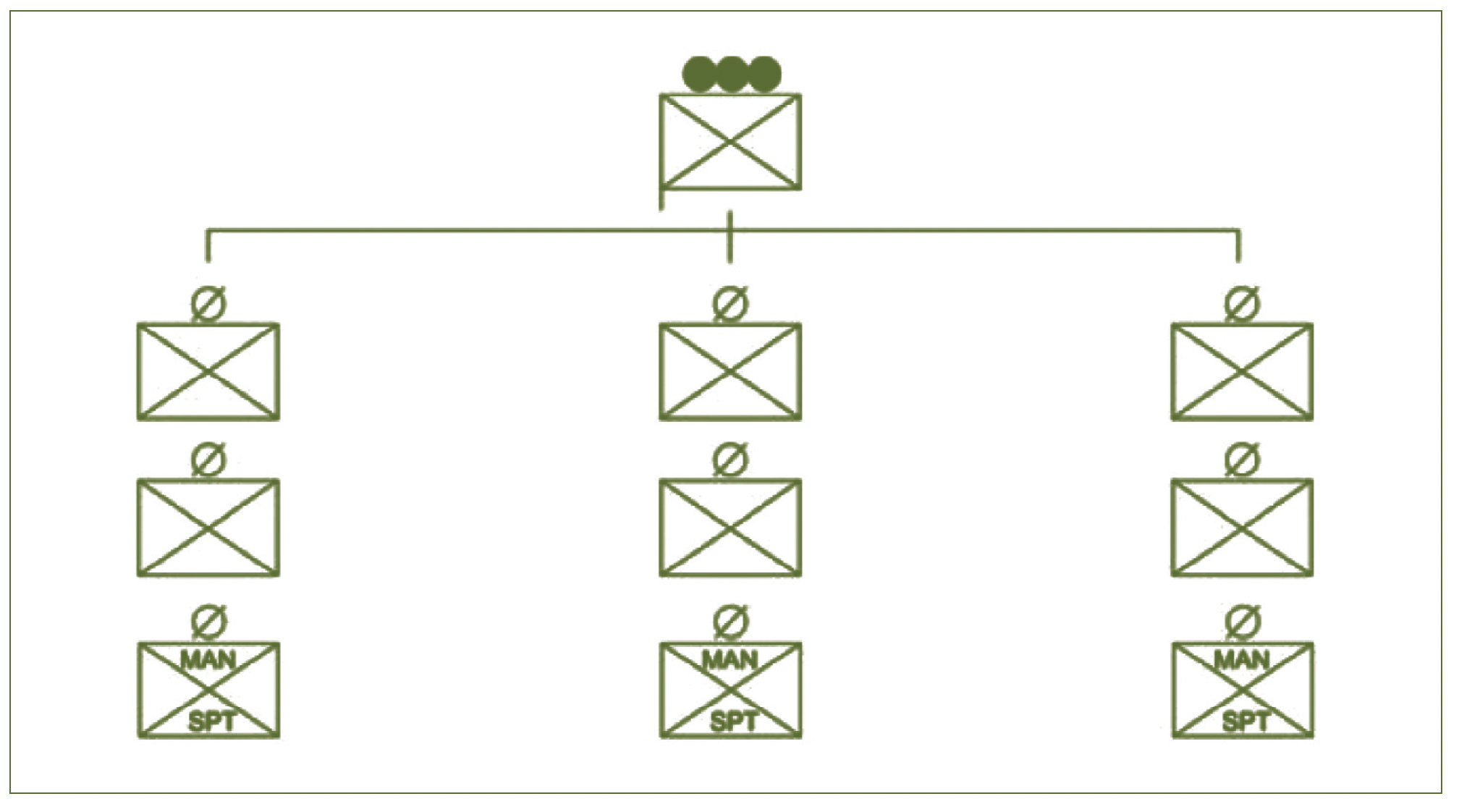

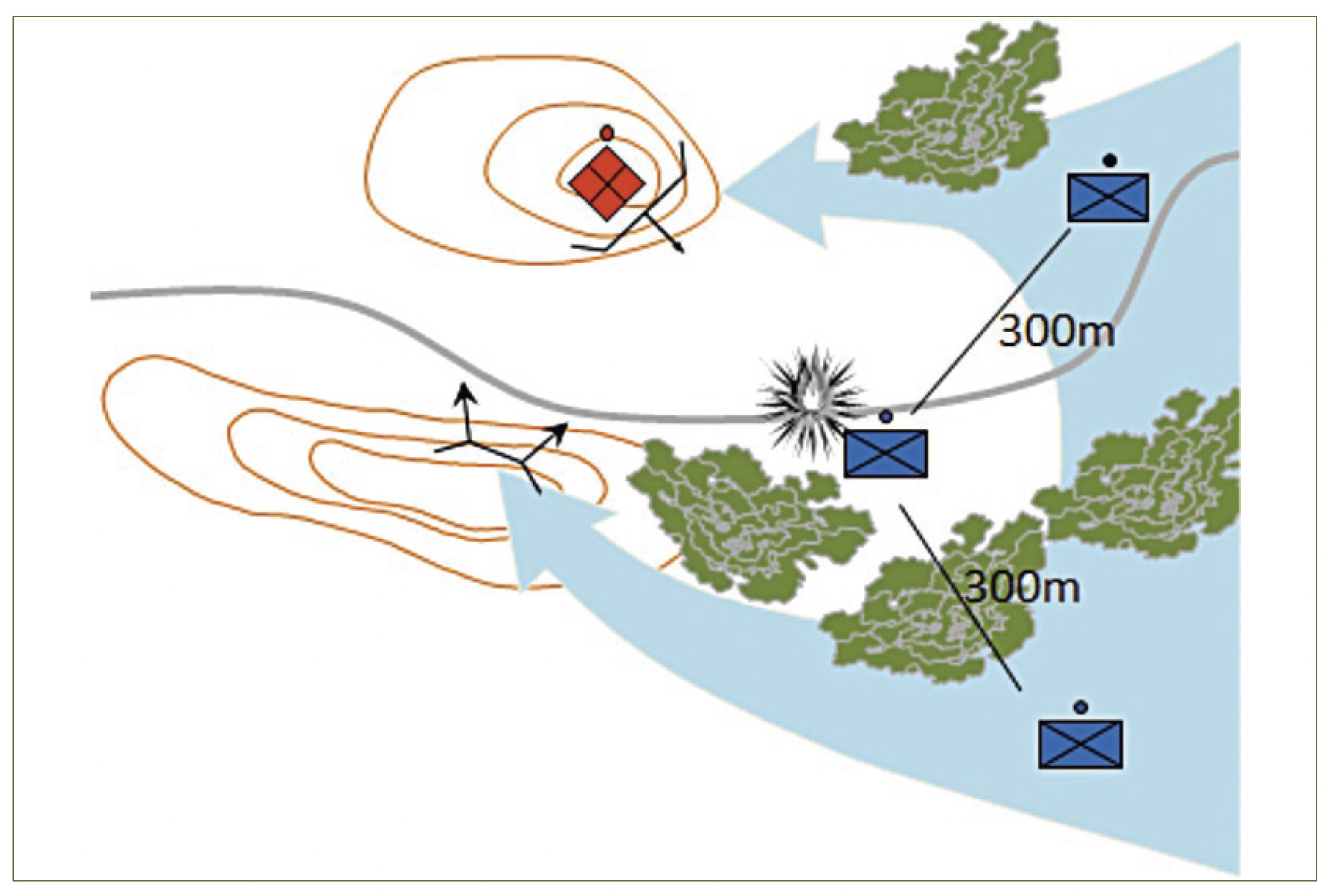

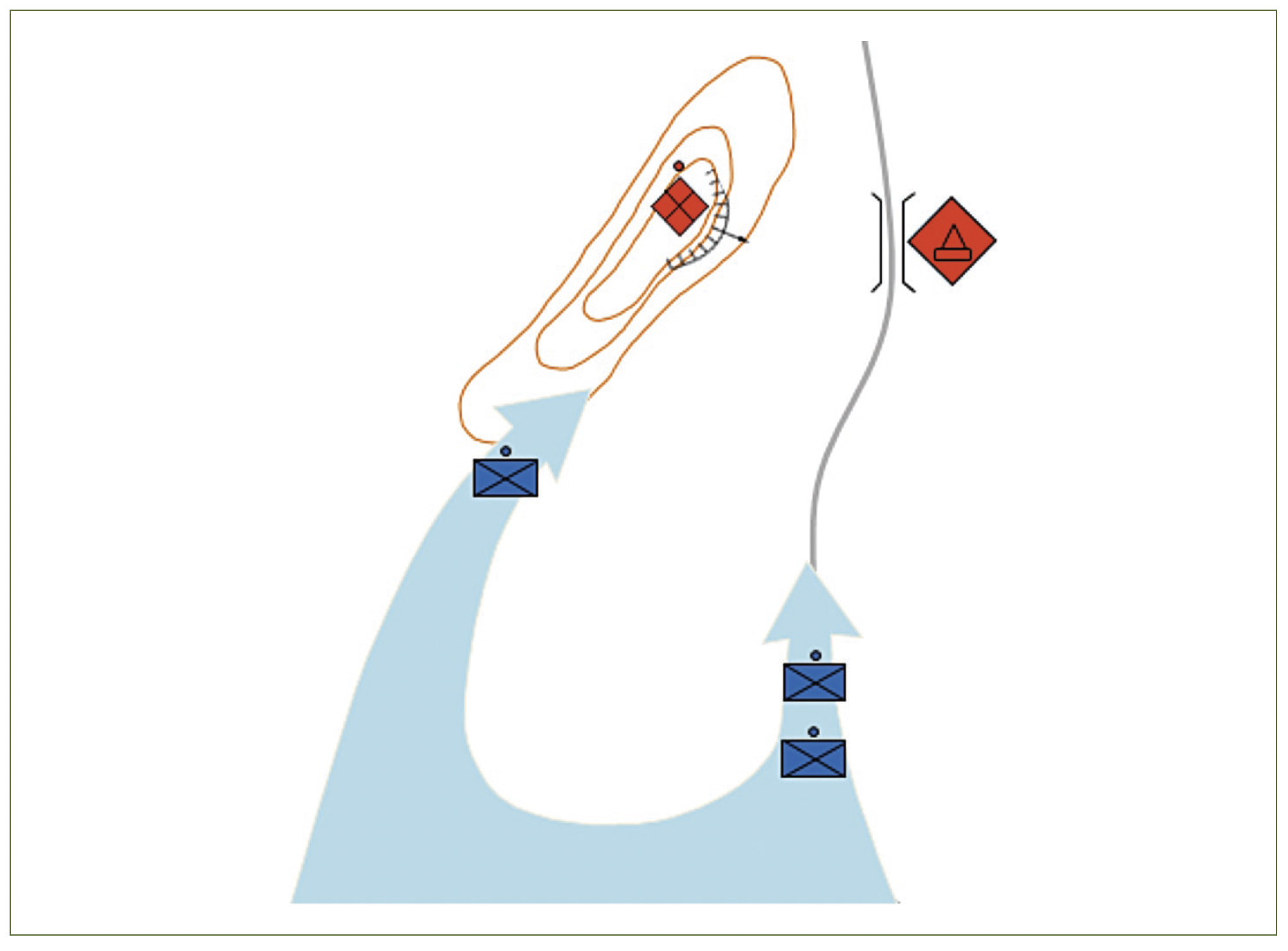

By attaching a MST to each of his sections, the platoon commander holds three 12-man manoeuvre elements (three section model — see Figure 1).8 Each can theoretically provide its own security (depending on the threat) and engage targets at a distance of anywhere up to 2000 metres utilising the Mag58. Ideally, PHQ should be split across two sections. The platoon commander and signaller should be positioned within a forward section, while the platoon sergeant and platoon medic should be located within a section patrolling in depth. Including PHQ attachments, the strength of the three manoeuvre sections now sits at 14, 14 and 12. By dispersing these three manoeuvre sections along or across a patrol route and allowing them to manoeuvre independently of one another, the sections will still be close enough to provide intimate support if required (the distance of dispersal will depend on the terrain and threat). In this way, the platoon commander not only reduces his signature on the ground, but will also achieve a far greater level of surprise against an enemy which may initially assume that it has contacted a section plus element. With the range and weight of firepower now available down to section level and improved communication systems organic to the platoon, the platoon commander has the ability to significantly increase the level of dispersion between each section, provided that the correct control measures have been implemented and rehearsed. On contact with an enemy element, the platoon commander may allocate battle control to an on-scene commander until he arrives in location and can assume control. With the platoon operating as dispersed manoeuvre sections, swarm tactics can be utilised, with sections converging rapidly on a target from multiple directions (governed by control measures to prevent fratricide), utilising long-range or close- range fires to fix and destroy the enemy element coordinated by a variety of commu- nication systems previously not available. Figure 2 illustrates a possible swarming scenario. It is important to note that, during an assault, depth may be provided by the section conducting the assault (depending on the size of the enemy force) as it has an additional fire team at the on-scene commander’s disposal. Alternatively, depth may be provided by manoeuvre elements not in contact.

Figure 1. Three Section Model9

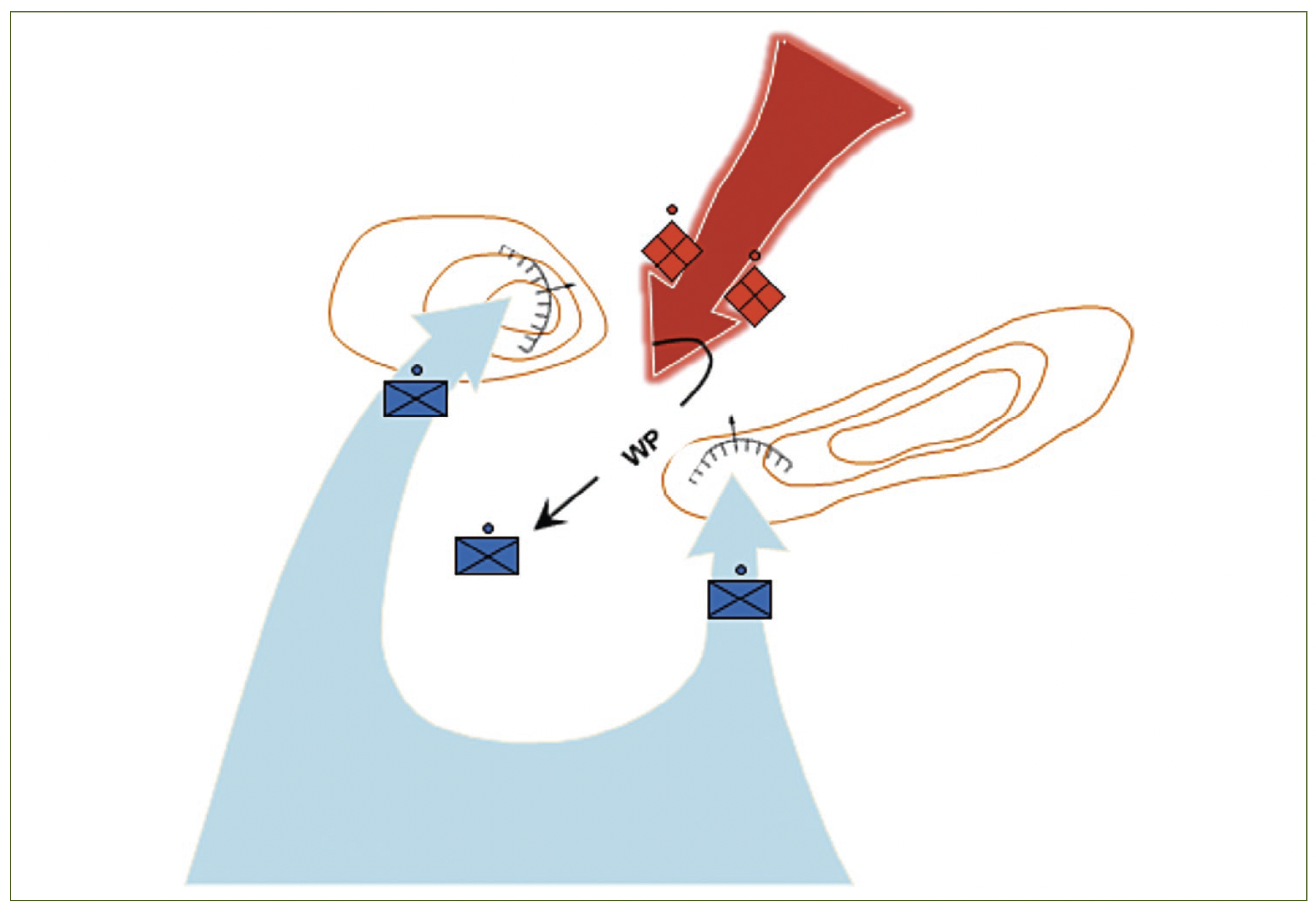

Depending on the scenario, the platoon commander may utilise alternative methods looking to achieve a push or pull effect. Circumstances may dictate that one of the manoeuvre sections creates a pull effect (Figure 3) by withdrawing through a designated engagement area, established by one or both of the remaining manoeuvre sections. Alternatively, the on-scene commander can exert a push effect by establishing and maintaining engagement utilising two manoeuvre elements and forcing the enemy to withdraw into a cut-off or blocking force established by the third manoeuvre section.

A conventional infantry platoon operating in mass provides an initial single linear threat to an enemy. The platoon may manoeuvre to threaten a flank or rear; however, such tactics are normally time consuming and likely to be detected. Unless direct or indirect fire is effective opportunities will exist for the enemy force to withdraw where it feels threatened by a superior force.

In contrast, swarming tactics are more likely to achieve a force multiplier effect both physically and psychologically. In circumstances where the enemy perceives that it has engaged a single section, the opportunity for surprise is considerably enhanced. Flanking semi-autonomous sections, not identified in the initial engage- ment, may simultaneously or successively engage in surprise attacks on the enemy flanks and to its rear. This will create confusion within the enemy over the direction of the main effort, its forces surprised by unexpected assaults and shocked by the realisation that their withdrawal route is cut off, thus destroying their will to fight.

Figure 2. Swarming

Figure 3. Utilising a Pull Effect

Further mission and threat-specific alterations can be made to the composition of these manoeuvre sections. Should he utilise the 84mm Carl Gustav with one of the manoeuvre sections, the platoon commander will have a light-skinned vehicle, hunter/killer group at his disposal. He can manoeuvre this group to the rear or flanks of the other two elements, closest to the most likely approach of enemy vehicles. Ideally, two 84mms should be utilised in mutual support, allowing the platoon commander to develop a manoeuvre section comprising two MST and a brick from another section. This would still leave him with three manoeuvre sections. In conjunction with this option, the platoon commander may also utilise the Mag58s at section level by having light support weapon (LSW) gunners who are qualified on the Mag58. This alteration will force the platoon commander to decide between the LSW’s mobility advantage as opposed to the Mag58’s weight of firepower and range overmatch.

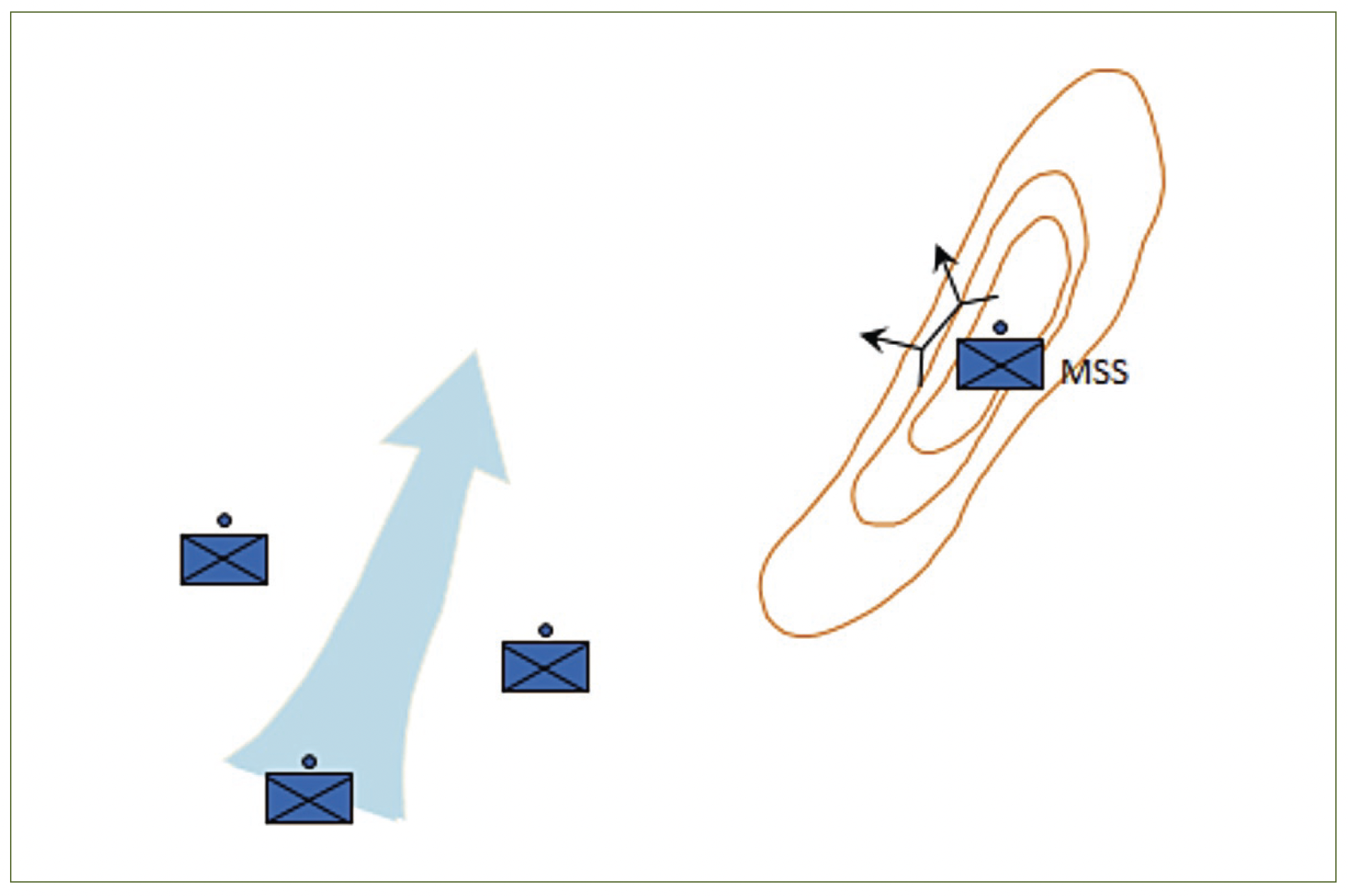

Depending on the terrain, the platoon commander may also look to utilise MSS complete as a bounding, organic overwatch position situated on key terrain within an area of operations. The positioned MSS can be incorporated with dispersed sections on the terrain below, capitalising on the relative security now provided by the increased firepower and weight of firepower organic to the IBM 2012 platoon (see Figure 4). This is a good example of the flexibility now available to the modern dismounted platoon commander as he is no longer as reliant on the direct fire support weapons platoon to provide that integral fire support when needed. Once on the ground he can adapt his scheme of manoeuvre as necessary.

Satellite Patrolling

Should the threat dictate that the platoon remain relatively congregated, the use of satellite patrols can provide security, physical depth and increased situational awareness. This means of patrolling, frequently ignored in Australian doctrine, can be utilised to deter ambushes, snipers and command detonation of IEDs. Satellite patrols utilise a base unit which controls smaller satellite units that leave and return to the base unit during the conduct of a patrol.10 The aim of the satellite unit is to increase the ‘buffer zone’ between the threat and the main body.11 This tactic forces the threat to increase its distance from the main body or risk being caught between the patrol elements.

Figure 4. Organic Overwatch provided by MSS

The advantage of satellite patrolling lies in its unpredictability to the enemy.12 The size of friendly forces, location and overall axis of patrol remain unclear to enemy intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance if executed correctly. In addition, the platoon commander still has a manoeuvre element(s) available to use on contact with the enemy. As described in FM 3-24.2 Tactics in Counter Insurgency, the organisation of the patrol should incorporate as a minimum one base and one satellite unit, the size of each unit dictated by the situation on the ground.13 With the incorporation of MSS at platoon level, the commander now has a plethora of possibilities at his disposal to suit the mission requirements. By applying the three section model, the platoon commander can utilise one of the sections as a satellite unit, patrolling in proximity to the base unit. The satellite patrol can move away from the base unit for short periods of time, identifying and investigating locations that can be used as command positions for neighbouring IEDs and clearing dead spaces or potential ambush sites (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Satellite Patrol investigating Potential Ambush Location

Conclusion

In future conflict it is widely accepted that the Australian Army will have to learn to fight nimbly against an array of armed adversaries who are likely do all they can to avoid the confrontation of a traditional force-on-force battle. By reducing signature and predictability, increasing responsiveness, improving manoeuvrability and empowering section commanders with far greater mission command, well- rehearsed dispersed patrolling and swarm tactics will allow platoon commanders to take full advantage of the benefits that the IBM 2012 structure provides. The alternative methods discussed in this article are a base level for platoon commanders to begin delving deeper into the possibilities and variations to TTPs now available with the IBM 2012 structure. As the characteristics of dismounted combat platoons within LWP-CA 3-3-1 increasingly dictate the use of small, semi-autonomous teams and swarm tactics, further development of TTPs needs to occur. Only when TTPs are more closely aligned with these characteristics can the overarching intent of ACR Infantry 2012 and its vision for success in close combat be achieved.

Endnotes

1 Land Warfare Development Centre, Army Capability Requirement, Infantry 2012,

Puckapunyal, 2006, para 2.14.

2 Ibid.

3 S.J.A. Edwards, Swarming on the Battlefield: Past, Present and Future, RAND Corporation, USA, 2000, Chapter 5, p. 69.

4 S.J.A. Edwards, Swarming and the future of Warfare, RAND Corporation, USA, 2004, Abstract.

5 J. Arquilla and D. Ronfeldt, Swarming & The Future of Conflict, RAND Corporation, USA, 2000, Summary, p. VIII.

6 Edwards, Swarming and the future of Warfare, Abstract.

7 Arquilla and Ronfeldt, Swarming & The Future of Conflict, Summary, p. VI.

8 LWP-CA (DMTD CBT) 3-3-1, Dismounted Minor Tactics 2010, para 2.51.

9 Ibid., Figure 2-7.

10 FMI 3-24.2, Tactics in Counter Insurgency, 2009, para 5-212.

11 ‘Ideas and Issues – Snipers’, Marine Corps Gazette, September 2007, p. 44.

12 FMI 3-24.2 Tactics in Counter Insurgency, para 5-212.

13 Ibid., paras 5-213, 214.