Matching Supply and Demand in ADF Specialist Health Support: A Proposal

Abstract

The Australian Defence Force has a need for procedural medical specialists in garrison healthcare, on major exercises and on operations. Employing such specialists in the full-time component of the ADF has proved largely impossible, leading to reliance on civilian contractors. However, the ADF Reserves include many procedural medical specialists who could potentially perform this work. Underemployment of the Reserves is a costly lost opportunity. This article proposes a method of better matching resource to requirement that would reduce reliance on expensive civilian contractors, increase ADF capacity, reduce wasteful expenditure on the Reserves, and provide a more viable option for procedural specialists wanting a military career.

Preface

This article concentrates on the provision of specialist procedural medical support to the Australian Defence Force (ADF). These functions are largely performed by either civilian contractors or Reserve personnel. Other essential aspects of garrison and deployed medical care, such as primary care, rehabilitation, public health and occupational medicine, are principally performed by full-time ADF personnel. Reserve procedural specialists—specifically general surgeons with knowledge of trauma surgery and orthopaedic surgeons (both with Fellowships of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons), anaesthetists (Fellows of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists) and intensive care physicians (Fellows of the College of Intensive Care Medicine)—have been essential to many recent ADF deployments. These specialties also receive the bulk of contracted private medical billing in garrison healthcare. In concentrating on procedural specialties, the intent is not to devalue the contribution of other Reserve medical specialists, general practitioners, career non-specialist doctors and doctors-in-training, nor to ignore the work of nursing and allied health practitioners. The proposal made in this review might apply equally to each of these groups.

Situation

The ADF needs the services of procedural medical specialists in three main areas.1 First, in garrison healthcare, where soldiers require procedures as a result of injuries or illness, whether or not acquired in the course of their ADF service. Garrison procedural specialist medical care is currently largely provided by private practitioners in private hospitals. Second, on major operations, as both ‘real world’ support in the event of major trauma in a location remote from civilian medical infrastructure, and as ‘exercise’ support for the operational, logistic and medical aspects of the exercise. Third, on operational deployments overseas.

At present, the ADF relies heavily on civilian contractors in each of these three areas.2 Contracting has provided a clinically effective—though expensive—solution. However, a large number of procedural specialists in the ADF Reserve are substantially underemployed. Many are particularly frustrated by the lack of opportunity for overseas deployments, and indeed, some have resorted to working as civilians (for salaries much greater than those on offer in the Reserve) for the organisations that are contracted to the ADF.

Factors Explaining the Current Situation

The ADF has only one full-time procedural specialist: a naval orthopaedic surgeon, who also works in civilian practice in order to maintain a diverse skill-set. While the ADF has occasionally been able to attract other surgeons, anaesthetists and intensivists into its full-time component, the scope of clinical practice in garrison healthcare is insufficient to maintain the required range of clinical skills. Even if there was a sufficient quantity of work available, these doctors must work primarily in civilian hospitals in order to maintain proficiency. Historically, ADF full-time conditions of service have been substantially worse than those for equivalent civilian practitioners. Paid less than half their colleagues’ wages for the same work, there have also been the added disadvantages of uncertain future posting locations and the possibility of deployment at short notice. It was not surprising that specialists employed in such positions did not remain in the full-time component of the ADF for very long.

Even if there was a sufficient quantity of work available, these doctors must work primarily in civilian hospitals in order to maintain proficiency.

In contrast, the ADF has some success in recruiting full-time general duties medical officers. Full-time medical officers recruited through the undergraduate sponsorship scheme are able to integrate part of their postgraduate training into their military service while at the same time providing primary care under remote supervision. Most are encouraged to train in general practice as many ADF postings are accredited by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Training in procedural specialties is more difficult. Full-time training in civilian hospitals takes at least seven to eight years from graduation. As it is impossible to work full-time in a civilian hospital while also working in the ADF, this is not a realistic source of procedural specialists. Moreover, even if a full-time doctor was committed to this career path, qualification after ten to twelve years of part-time training would be long after the return of service obligation was passed, presenting the same problems of retention as those described above.3

From time to time, better conditions of service are entertained as a means of attracting a limited number of procedural specialists into the ADF’s full-time component.4 Even if two or three doctors in each specialty could be appointed, this is unlikely to guarantee the ability to provide year-round staff to a deployed surgical team, or to respond to emergencies at very short notice.

These factors combine to ensure that the ADF’s ability to perform surgical operations under general anaesthesia in the garrison, exercise and operational environments will continue to rely exclusively or nearly exclusively on Reserve or contracted civilian medical procedural specialists.5

Nature of the Problem

Reliance on the Reserves for procedural specialist medical personnel is not necessarily a problem, at least in terms of the skills required. In each of the three environments they are employed (garrison, exercises and operations), familiarity with the military environment confers many advantages, including an appreciation of the occupational health implications of treatment options, a willingness to work in suboptimal conditions and with portable equipment, and an understanding of military command structures and the role of healthcare in the overall operational plan. For this reason, civilian contractors often prefer to employ doctors with previous military service. The essential military skills are nonetheless relatively limited, and outside command roles procedural specialists appear to function well after one to two years of non-continuous Reserve service along with three to four 2-week courses. In terms of knowledge acquisition, there would appear to be no great advantage to having such doctors in the full-time component. The bulk of the ongoing training liability for procedural specialists is their continuing medical education. In Australian state public health services this requires up to four weeks of leave per year, in addition to a large financial allowance. For Reservists, this cost is borne by state departments of health and by the doctors themselves rather than the ADF. By relying on Reservists, the ADF also avoids the cost of superannuation, leave, medical indemnity insurance and practice overheads.

... civilian contractors often prefer to employ doctors with previous military service.

There is a large pool of Reserve procedural specialists who could potentially work in each of the three environments. The ADF’s operational focus in the last eight years has been an effective recruiting tool, with most entrants during this time joining with the intention—that is rapidly downgraded to hope—of working on an overseas deployment. There is an understanding that providing support on major exercises is a necessary prelude to such deployments, as is the acquisition of military skills, not only on the Specialist Service Officer courses but also the All Corps Officer Training Continuum and Logistics Officer series of courses. As the dates of these courses and exercises are usually known six months to a year in advance, organising time away from public hospital practice is rarely a problem.

Even doctors engaged in private practice no longer have a significant financial disincentive, as the Employer Support Payment Scheme6 covers at least part of a doctor’s practice costs while away.

In summary, there is a large pool of highly experienced procedural medical specialists who have completed the necessary military training and are willing to work for up to a few months at a time, for less than they are paid in their civilian employment, in support of the ADF. Why does the ADF rely on civilian contractors rather than utilise this resource?

As currently administered, the procedural specialists in the Reserves are rightly perceived as an unreliable source of manpower by some in the full-time component. Commanders of the specialist medical elements of the Army Health Support Battalions receive regular requests for surgical and even general-duties medical officer support to major and minor exercises in Australia. These requests are typically less than two months in advance of the task. Virtually no doctor in public hospital practice is able to reorganise their roster with such little notice without calling in substantial favours from colleagues, all of whom then have to reorganise other aspects of their work (such as private practice, academic and administrative work) to accommodate the request. Most doctors in private practice have appointment bookings at least two months in advance. At the same time, doctors perceive the ADF as unreliable. A doctor who volunteers to support a particular exercise and rearranges his or her schedule to accommodate this can often find the task cancelled by the ADF at short notice, leaving them with no income during this period and having expended considerable goodwill from patients and colleagues. Task requests are therefore routinely not filled.

Virtually no doctor in public hospital practice is able to reorganise their roster with such little notice ...

In contrast to inability to support routine tasks, procedural medical specialists (along with others) have often made extraordinary efforts to respond to emergencies. Humanitarian aid deployments to Pakistan and Banda Aceh were easily staffed at extremely short notice. A number of factors are responsible—the relative ease of asking a colleague to contribute to such a high profile mission by covering gaps in a civilian roster, the understanding of patients who need to be rebooked, and the knowledge that such events do not occur frequently and that they warrant calling in the once-in-five-year favour. Paramount, of course, is the attraction of the task itself, which is also why there is seldom a difficulty finding volunteers for more prolonged operational deployments, given sufficient notice. This unfortunately leads to criticism that Reserve medical specialists only want to work with the ADF in high-profile desirable activities, a seemingly unprofessional approach.

For specialist medical support in Australia, the ADF provides the equivalent of private health insurance to its 55,000 full-time members, allowing quicker access to specialist opinions and procedures and a quicker return to work.7 This is very costly: $261 million was spent on purchased health services in the 2008/09 financial year.8 The referral habits of ADF primary-care doctors is no different to other Australian general practitioners, who choose procedural medical specialists on the basis of familiarity, past positive experience and an understanding of their particular areas of expertise. Not surprisingly, ADF members are often referred to specialists who are in the Reserve. However, very few provide such services on their Reserve time.

Not surprisingly, ADF members are often referred to specialists who are in the Reserve. However, very few provide such services on their Reserve time.

The current system of employment of Reserve procedural specialists and use of contracted civilian providers has therefore led to the following problems:

- Inability to reliably provide uniformed surgical support to major exercises and operations, with consequent expensive reliance on civilian contractors.

- Reservists working as civilians with contractors in support of field exercises and overseas operations, and as private practitioners in garrison healthcare in Australia, at considerably greater cost to the ADF than if they were working on Reserve time.

- The Reserves being perceived as an unreliable and (from a military if not clinical perspective) unprofessional source of health support.

- Frustration amongst Reservists that the ADF does not allow them to do what they joined to do, while at the same time making demands in training time which come at a financial cost.

- Wasteful ADF expenditure in using the Reserve service of procedural medical specialists in tasks such as first aid training for medics or attendance at administration courses.

- A sense amongst Reservists that the ADF has little appreciation of the realities of public hospital or private practice, when, for example, it makes requests for support with only two months’ notice or when it cancels tasks at short notice.

The Solution

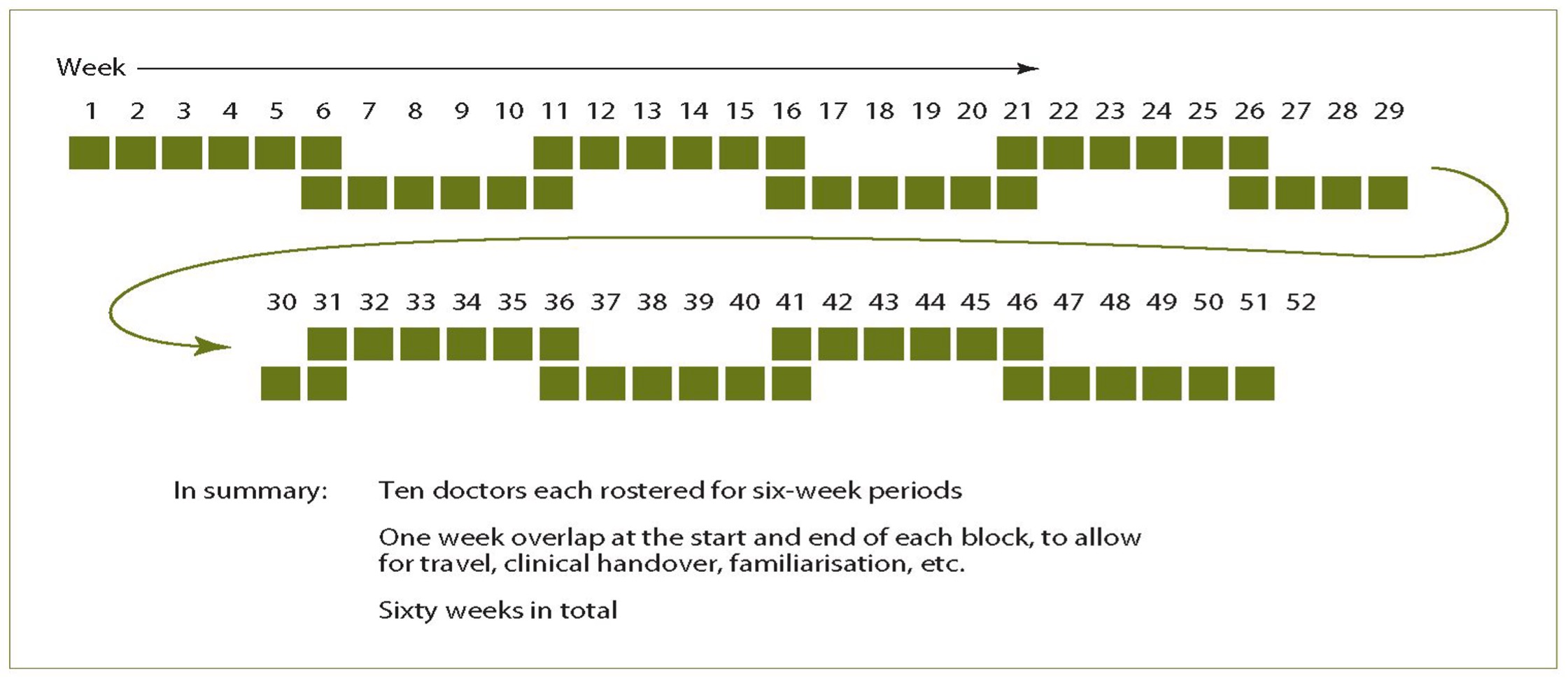

Each of these problems would be addressed by adopting a roster of doctors in each procedural specialty that would guarantee to employ the rostered practitioner for the duration of the nominated period (say, six weeks) with an overlap of one week at each end, as shown in figure 1. The total commitment would be ten doctors and sixty paid weeks in each specialty.

The essence of this scheme would be to guarantee work during the rostered period. Clearly, it will not be possible to know a year or more in advance what this work would be, but it is difficult to imagine that the ADF would be unable to find some form of productive task during each period. The primary focus—as for the rest of the ADF—should be support to operations. If the rostered doctor was considered ‘first in line’ for any operational deployment during the rostered period, signing on to the roster would become highly attractive to many. However, even doctors understand that deployments cannot be manufactured to satisfy their wish to serve overseas. In the absence of an operational need, the rostered doctor could be used in support of major exercises, in the development of policy and equipment relevant to their specialty, and perhaps most importantly from the perspective of the ADF, in the provision of garrison healthcare for ADF members as an alternative to using contracted private medical practitioners. ADF surgical inpatient facilities at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney,9 and possibly elsewhere around Australia, would clearly benefit from the continuous presence of ADF specialist medical staff. Co-location with a large civilian medical facility would still allow such staff to be removed for operations or exercises at short notice, with little impact on patient care.

ADF Reserve medical specialists serve in all three services. While the singleservice training requirements vary dramatically in time and content, procedural specialists employed exclusively in clinical roles do not draw heavily on their singleservice experience. Recent deployments to Afghanistan, in which Royal Australian Navy doctors have worked successfully in teams from both Army and the Royal Australian Air Force, attest to this. Therefore, to begin with, it is proposed that this roster scheme be tri-service and administered by Joint Health Command.

Figure 1. Year-long roster for one specialty position

In addition to requests for surgical teams on exercises, general-duties medical officers are also frequently sought from the Reserves when the full-time component cannot provide sufficient support. Specialists on the proposed rosters could also be used in these roles. While this would underutilise their clinical skills, this would be offset by the value to their general military training and also their ability to provide higher level specialist instruction to the full-time component. However, a similar roster scheme for Reserve general practitioners or non-specialist doctors able to perform general medical duties under remote supervision would equally fill this need. Units that are unable to identify the need for a medical officer more than two months in advance would then have the guarantee of a Reservist to fill the position if a full-time member was not available.

... general-duties medical officers are also frequently sought from the Reserves when the full-time component cannot provide sufficient support.

The system proposed would have many attractions for individual Reservists. Rather than having to rearrange civilian commitments, Reserve service could be integrated into a job plan in the same manner as occurs with hospital appointments. Few Reservists would find it difficult to commit to a six-week period given sufficient notice. Reserve service would change from an ad-hoc series of events that is justifiably considered by many as a ‘hobby’, to a core clinical commitment. However, not all Reservists would need to be on the roster every year. Eligibility for entry onto the roster would be a career goal and milestone, giving purpose to the completion of the various initial entry and professional courses required by the ADF. The skills required by rostered doctors would have to be actively managed, but the certainty of employment would make the acquisition of extra clinical skills a valid continuing medical education activity. Such training could be actively managed by the chairs of the relevant clinical consultative groups.

The ADF would derive numerous benefits from such a system. There would be more certainty that a specialist team could deploy at short notice, or on a continuous rotating basis, than is currently the case, or would be the case even if a small number of full-time specialists could be recruited. The financial cost of medical procedures performed in Australia could be substantially reduced in comparison to the current reliance on private practitioners. A large pool of ‘highly deployable’ Reserve specialists would emerge, reducing the overdependence on key personalities that has characterised deployments in the last ten years. While they would usually concentrate their Reserve service to a limited number of ADF health facilities, these doctors would be drawn from all around the country. This would allow the ADF to more effectively use the largest pools of medical expertise (in Sydney and Melbourne) to provide support to the largest concentrations of ADF members in northern Australia.

Cost Estimate

Procedural medical specialists are paid at Medical Level 4. Most procedural specialists are majors, earning $452.05 per day. In addition, the Employer Support payment for Reserve procedural specialists is $5600 per week. Therefore:

a. Each specialist would receive $18,986 (tax-free if on Army Reserve Training salary; taxed if on continuous full-time service) + $33,600 Employer Support Payment taxed for a six-week commitment

b. The total cost to Defence (including employer support payment) over one year would be $525,860 in each specialty.

This total cost figure appears quite large. However, in comparison with the $654 million currently spent by the ADF on garrison health services the figure is relatively small. 10 Reduction in expenditure on contracted health professionals was identified as a goal in the recent Australian National Audit office report on the provision of healthcare to the ADF. 11 In the 2008/09 financial year, the ADF spent $24.7 million on the Employer Support Payment scheme, 12 so even as a proportion of the figure currently spent on Reservists, the proposed expenditure is not unrealistic.

Reduction in expenditure on contracted health professionals was identified as a goal in the recent Australian National Audit office report on the provision of healthcare to the ADF.

Alternative Course of Action

There are a number of alternatives to the system proposed:

a. Continue with the current situation. This will mean continuing to support deployments in Timor Leste and the Solomon Islands with contracted civilian surgical teams, being unable to reliably provide surgical teams to support major exercises in Australia, and being uncertain of the ability to continuously staff even a limited surgical facility in an operational area thought too unsafe for civilian contractors. It will also mean continued reliance on civilian private practitioners for garrison healthcare. This approach calls into question the very need for the ADF to maintain any ability to provide surgical support in the field or at sea.

b. Develop a cohort of full-time specialist procedural medical officers. This would probably be a more expensive approach to developing the same capability, would not make use of existing resources, and would perpetuate a culture of having a ‘chosen few’ repeatedly selected for desirable tasks. The system would be more vulnerable to the possible appointment of doctors unsuited to their role, to the possibility of high staff turnover, and to the concentration of expertise amongst a select few.

c. Establish a roster in which Reserve medical specialists would agree to be ‘on call’ for short notice employment on exercises or deployments. This would not facilitate garrison healthcare (as described above) and would be markedly less attractive to most Reservists, as many civilian hospitals would require such a period to be free of clinical commitments. As the ADF would in essence be asking Reservists to take six weeks without pay, such a system would be unlikely to succeed.

Course of Action Development

Development of the proposed course of action will require:

a. Formal costing in comparison to current expenditure, much of which is not in the public domain;

b. Definition of the skills required for appointment to the roster in each specialty, and establishment of a clinical governance and administrative structure to support the work of the clinicians appointed; and

c. A call for expressions of interest amongst relevant specialist groups in order to confirm the viability of the scheme using current resources.

Conclusion

In recent years the ADF has successfully relied on a disaster management approach to staffing its deployed surgical facilities, at the same time as increasing its dependence on contracted specialist medical support. This has ignored the large, expanding and capable pool of Reserve specialist medical officers. Adoption of the system proposed could better align resources with need, increasing operational capability and reducing cost.

Endnotes

1 ‘Defence’s Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia’, Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, 2010.

2 Aspen Medical, <http://www.aspenmedical.com.au> 2010.

3 P Wilkins, ‘Retention of staff is still a problem’, ADF Health, Vol. 9, 2008, p. 1.

4 ‘Defence’s Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia’.

5 Ibid.

6 D Stedman, ‘Financial support: helping Reserve service by health professionals’, ADF Health, No. 8, 2007, pp. 22–23

7 ‘Defence’s Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia’.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Defence Reserve Support Council Report, <http://defence.wunderman.com.au/enewsletters/20090801/LP/lpage.html> 2010.