Reclaiming Volunteerism: How a Reconception an build a more Professional Army Reserve

Abstract

The focus of the Army Reserve has shifted from supplying deployable units for large-scale conventional warfare to providing individuals and small groups to support the Army’s current operations. The requirement for soldiers to be easily integrated into Regular units has caused us to increasingly train, treat and manage reservists identically to their full-time counterparts. This is ineffective because it fails to accept the real and important differences between Regular and Reserve service. Reservists should actually be seen as sharing more characteristics with volunteers than part-time employees. The strategies used and many of the lessons learnt in the voluntary sector could be applied to increase the Reserve’s capability and performance.

Introduction

It was once commonplace to refer to the Australian Militia and Army Reservists as volunteers. The United Kingdom Territorial Army still routinely refers to members as volunteers and retains the term ‘volunteer’ in some unit names.1 Believing that the term ‘volunteer’ somehow diminished the standing of reservists, the Australian Army slowly discarded the term from its collective vocabulary.

Replacing ‘volunteer’, the Australian Army now describes Australian Regular Army (ARA) members as ‘full-time’ and Australian Army Reserve (ARes) members as ‘part-time’. This perpetuates the popular mythology that reservist and regular soldiers are distinguishable only by the number of hours they work. This conception denies the extensive differences in motivators, experiences and capabilities of reservists. This article argues that a more accurate picture is gained of reservists if we conceive of them not as employees but as volunteers. This reconception provides a more realistic picture of the potential and limitations of our Army Reserve while prompting us to abandon the unhelpful belief that we can treat reservists in the same way as members of the Regular Army. If we adopt this reconception of reservists as volunteers we can begin drawing on the burgeoning research and literature about volunteer management. It should also prompt us to reassess whether our methods of training, rewarding, leading and recruiting are appropriate for a volunteer environment. Accepting reservists as volunteers, and adjusting our practices accordingly, will counterintuitively provide a more professional Reserve.

A Changing Role for the Army Reserve

The Defence White Paper 2000 announced that:

The strategic role for the Reserves has changed from mobilisation to meet remote threats to that of supporting and sustaining the types of contemporary military operations in which the ADF may be engaged.2

A decade on from this strategic overhaul and after the release of another white paper3 it is useful to evaluate how we conceive reservists.

The birth of the modern Reserve began in 1947 when Australian military forces were divided into the Australian Regular Army and the Australian Citizen Military Force. Australian defence planners had previously relied primarily on part-time militia forces. It was the decision to establish a permanent standing army in addition to a citizen force that created the modern distinction between part-time and full-time soldiers. It is this current dichotomy that this article seeks to understand and address.

The Defence Act 1903 illustrates the expanding role of the Reserves in Australia’s national security infrastructure. In 1964 call-out of reserve forces was extended to circumstances other than war and the geographical limits were removed from the legislation. Further amendments in 1988 and 2001 expanded the Reserve’s ability to be called out for situations ranging from war to community activities of significance to humanitarian aid.4

The likelihood of Australia confronting an existential threat from a nation-state is so small as to be insufficient as the sole raison d’etre for a reserve army.5 While threats from invasion have continued to diminish since the end of the Cold War, Australia’s participation in overseas operations has rapidly increased. This has stretched parts of the Regular Army and it is now the role of the Reserve to provide individuals and small groups to supplement Regular Army contingents on operations. The Army Reserve has also been tasked with providing larger groups for Operation ANODE, Operation RESOLUTE and Defence Assistance to the Civil Community operations.

'Integratable' Solderies and the Professionalism Myth

Under its former role, the Reserve Army would only be mobilised in times of national crisis. If reservists were required they would be deployed as part of their existing units and they would not need to integrate into ARA forces. However, with the Reserve’s current task of providing individuals and small groups to support the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) current operations, commanders are shifting their focus from maintaining a unit that is able to deploy en masse to building a reservoir of trained individuals with the capacity to integrate into Regular Army forces. The capacity to integrate into ARA teams about to deploy on operations is the benchmark against which reservists are now measured. Changing the role of the Reserve is a sensible response to an evolving strategic and military landscape, but the desire to have ‘integratable’ soldiers has resulted in the damaging trend to move the management, training and readiness requirements of reservists ever closer to the ARA standard.

The capacity to integrate into Regular Army teams about to deploy on operations is the benchmark against which reservists are now measured.

The requirements to make a reserve soldier ‘integratable’ into a Regular Army unit are increasing inexorably. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of days required to train a Private-equivalent soldier in the Reserve has almost trebled over the past twenty years. Since 1997 Army reservists have been required to maintain their Army Individual Readiness Notice level at the same standard as the Regular Army. Reserve soldiers are managed in a very similar way to their ARA counterparts and reservists receive the same annual performance reviews and follow a similar promotion procedure. Some argue for even more assimilation by unifying the Reserve pay and conditions of reservists and regulars.6

The alignment of ARes standards with their ARA counterparts is a result of the professionalism myth. The professionalism myth maintains that if a reservist is to maintain the same professional level as the ARA, and therefore be easily integrated, then training, recognition, management and leading must be the same as a regular member. The myth borrows from the private-sector concept where full-time and part-time employees are treated almost identically. The professionalism myth is ultimately false because it does not appreciate the unique motivators and characteristics of reserve service.

Reservers' Work Is different to Part-Time Work

A consideration of the nature of Army Reserve service shows a number of superficial similarities with civilian part-time work. Reservists attend on a regular basis and are paid for the hours they work, at a rate determined by their skills and qualifications. High-Readiness Reserves and members of the Reserve Response Force are paid bonuses for undertaking particular training and readiness requirements. Reservists receive additional compensation such as health bonuses, access to the Defence home ownership scheme and other employee benefits.

These superficial similarities are deceptive. In reality, the motivation of a reserve soldier is dramatically different from a part-time employee. There are some younger reservists who join the Army while they are undertaking education and training, but these are a minority. The majority of reserve members undertake their service in addition to full-time employment; this is unusual because only 6 per cent of Australians work in two occupations and an even smaller percentage of these have a second occupation in addition to full-time employment.7 This tells us what we already know: if Reserve service suddenly ended, the majority of former reservists would not take up another occupation in its place. The reason why members work in the Reserve when they would not undertake any other type of part-time work is simple—reservists do not consider their service as work.8

... if Reserve service suddenly ended, the majority of former reservists would not take up another occupation in its place.

Voluntariness Rather Than Compulsion

The problem with the ‘professionalism myth’ is that it denies some of the fundamental differences between ARA and ARes service. Those who join the modern Australian Army are volunteers; they are not conscripted or compelled into compulsory national service. However, after enlistment the ARA member’s career will be dominated by compulsion. Initially the member will be subject to a Return of Service Obligation legally proscribing the individual from leaving the Army. During their service the organisation will be able to tell them where to live, which job they will be performing and they may be legally obliged to deploy on operations. If the member does not attend work they will be charged with a military offence. Moreover, for most ARA members the Army is their sole source of income so they are compelled to work for economic reasons. In other words, an ARA soldier is compelled to attend the Army by a number of strong economic and legal ‘push’ factors.

In stark contrast to the compulsion of Regular Army service, a reservist’s life in the Army will be characterised by voluntariness. The average Army reservist experience consists of attending parade nights and training weekends. Occasionally the reservist may complete a course or attend an annual exercise. While commanders and leaders may deem certain events compulsory, no member is ever compelled to attend. Commanders have the legal capacity to charge a member for being absent without leave but this authority is seldom used because commanders do not want to further deter members from returning to their roles. Reservists have almost total control over whether they attend trade or promotion courses and can leave the service at any time by either discharging or by not attending training or parade activities. The vast majority of reserves also have other occupations providing them with another source of income and therefore are not compelled to attend training for economic reasons. Reservists are routinely sent overseas on operations, but modern Reserve deployments are optional with the individual electing whether to deploy.

The vast majority of reserves also have other occupations providing them with another source of income ...

The voluntary nature of Reserve service, combined with the perception of members that Reserve service is not work, should prompt us to see them not as employees but as volunteers. The term ‘volunteer’ should not be seen as pejorative, but as recognition that while the reserve members may perform a very different role to a children’s soccer coach or soup kitchen attendant they have similar motivators and experiences. Reservists, in many ways, share more with a local State Emergency Service volunteer than their ARA counterparts. Failure to accept the voluntary nature of Reserve service ultimately results in less effective training, leadership, recognition and recruitment processes.

What Does a Reconception of Reservists Mean?

The Modern Volunteer

Treating Army reservists as volunteers would seem irreconcilable with the increasing complexity of their role. First we must disabuse ourselves of the falsehood that volunteers cannot perform at a professional standard. With demands on volunteer organisations continually growing, volunteers are required to fill a number of demanding and complex roles. The requirement that community organisations comply with a duty of care to their volunteers, staff, customers and the general public has dramatically increased their training requirements. Many volunteers require occupational health and safety lessons, child abuse mandatory reporting training and police background checks just to begin learning their new role. Volunteers in a rural fire service are required to understand firefighting theory, the operation of a number of vehicle variants, communication equipment, and firefighting theory, personal protective equipment, and use these under situations of extreme physical danger. Much of Australia’s emergency response infrastructure is built around these volunteers, with communities trusting them with their lives. The success of these organisations’ recruiting methods is demonstrated by the fact that there are approximately ten times the number of volunteer firefighters as a there are ADF Reservists.9 This should prompt us to question what lessons we can learn from these successful organisations and how we can use their strategies to build a stronger Reserve Army.

Volunteers Have Different Needs

Volunteering Australia, the nation’s peak volunteer body, argues that:

While the knowledge and skill required of a volunteer is the same as would be required of a paid worker performing the same task, volunteers will have different needs, will find different things rewarding, will have varying expectations of their volunteering experience and will value training differently.10

The remainder of this article attempts to identify what these differences are and how we can tailor the way we treat reservists to meet their unique needs and expectations as volunteers in order to build a stronger Army.

Unfortunately in our drive for the ‘integratable soldier’ we have made the classic mistake of having ‘simply transferred established employment practices from permanent staff into the volunteer area’.11 If we are to enhance our Reserve force then we must make a considered decision about which employment practices are equally applicable across the entire Army and when these volunteer reservists need distinct and customised solutions.

... we have made the classic mistake of having ‘simply transferred established employment practices from permanent staff into the volunteer area’.

The most important of the differences in managing employees and volunteers is that motivation is indispensible in a volunteer environment because of the voluntary nature of the experience. One of the major challenges facing the Reserve is the tendency for Reservists to join, receive expensive training and then leave the service.12 This is indicative of a system where training activities are not successfully building members’ motivation to attend. The sacrifices of an ARA member are extensive; members elect to continue to serve with the ADF instead of seeking external employment, accepting the hardships that accompany the life of a soldier. Reservists make sacrifices as well, but face a different choice. They are not required to forgo civilian employment to serve in the ADF. When attending an activity a reservist does so rather than spending more time with friends and family, pursuing a hobby or joining the local sporting team. The fundamental difference between the way reservists are trained, recruited, recognised and managed must support their choices to participate in the Army over other activities. The tasks necessary to make the Reserve a ‘volunteer-friendly’ experience can be grouped into training, leadership, recognition and recruitment. Lessons learnt from managing emergency services volunteers are most applicable as the role and volunteer model they present are most similar to the Reserves.13 By incorporating strategies to make the Army Reserve volunteer-friendly while still maintaining rigorous, or even heightened, standards of professionalism we can build an Army Reserve with members who are both citizen volunteers and proficient professionals.

Activities and Training

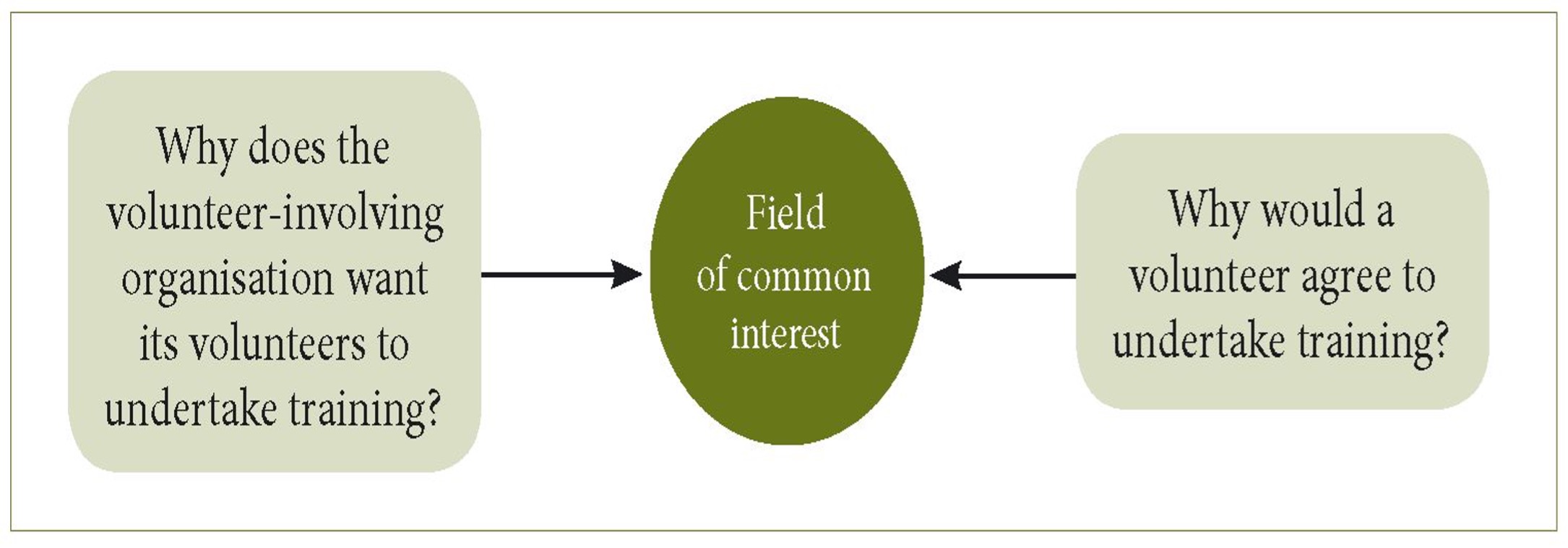

For the Army Reserve experience to become more volunteer-friendly, the most fundamental changes will be in activities and training. The increasing amount of training that reserves require to undertake their role should not itself be considered antithetical to a volunteer environment. If conducted successfully training can be one of the most effective tools to recruit14 and motivate15 volunteers; what we train and how we train will, however, need to be reassessed. Training must be relevant to a member’s service occupation because volunteers have been shown to have a limited interest in their non-core roles.16 Volunteering Australia observes that training in volunteer organisations has two goals; the capability of the organisation is enhanced by improving its human capital, while simultaneously ‘motivating volunteers by helping them achieve and maintain satisfaction in their role’.17 Therefore, the most effective training for both the organisation and the individual is one that fulfils both of these goals and that is the field of common interest (see Figure 1).

A prime example of an area of training that is important to the organisation but outside the area of volunteer interest, is the new requirement that all Reserve members holding the rank of corporal and above hold a competency in military risk management. The plan has the worthy goal of improving decision-making, but is also likely to lessen the motivation of volunteers. This type of training may marginally and temporarily improve the organisation as a skills gap is plugged, but in the long term it will have a detrimental effect on motivation and therefore the organisation’s capability.

Figure 1. Effective training for volunteers demands that it operates in the ‘field of common interest’18

The top two motivators of volunteering are ‘knowing that my contribution would make a difference’ (80 per cent) and ‘personal belief for a particular cause’ (67 per cent).19 A volunteer at a soup kitchen can see the homeless customer receiving and immediately consuming the food—the positive effect of the volunteering is obvious and immediate. In an Army context, although reservists make a very important contribution to Australian security, a direct and tangible effect is much more difficult to demonstrate to individual volunteers. Having such an intangible effect remains a fundamental challenge to motivating reservists. We need to ensure that we constantly reiterate that reservists have a positive and important role in Australian security. Moreover, reservists need to be given opportunities to complete tasks that have immediate and tangible results such as disaster relief and Defence Assistance to the Civil Community.

... although reservists make a very important contribution to Australian security, a direct and tangible effect is much more difficult to demonstrate to individual volunteers.

Leadership and Management

The leadership and management of volunteers should differ substantially from employees. In studies of volunteer firefighters one of the most common exclamations of respondents is, ‘Remember we’re only volunteers’—a statement that is interpreted to reflect a number of different volunteer emotions.20 The unspoken implications behind this statement of volunteer status are the feelings that ‘If we don’t like what you do we’ll stop being involved’; ‘You’re not my boss and I therefore have the right to question you if I don’t like what you say or do’; and ‘I don’t have to do anything I don’t want to’. It is neither possible nor desirable for all of these volunteer responses to be accommodated in a military context. However, these findings should prompt commanders to reconsider the type of leadership that is appropriate in the volunteer environment. Officers, warrant officers and non-commissioned officers are taught the Regular Army’s leadership style but are not given any training on leading volunteers. Insofar as it is consistent with the military environment, leaders should adopt a more egalitarian model when leading reservists.21

Volunteering Australia’s 2009 survey also indicated that volunteers are suspicious of bureaucracy, particularly if imposed from a distant headquarters.22 Reserve and ARA members alike would have noticed the increased the paperwork required of both individuals and units. Much of the corporate bureaucracy burden applies equally to ARA and reservists. Reservists, however, do not have the same time to complete these requirements and therefore spend a much larger proportion of their precious training time completing corporate governance tasks than their ARA counterparts. These tasks are placed on Reserve units in order to ensure accountability. Similarly, the administrative requirements placed on individuals aim to ensure that members can be integrated with the ARA. Although admirable in intent, the unintended consequences are that reservists, and the ARA members posted to Reserve units, spend a large proportion of their time completing administration tasks. Administrative and corporate governance activities do not fall in the field of common interest and so the long-term effect will be increased absenteeism and lower retention rates as members become dissatisfied and leave the service. A more careful and sophisticated application of administrative requirements on Reserve units and individuals would reduce the high levels of absenteeism and member turnover.

Performance appraisal procedures are an example of both leadership and administrative processes that have been unthinkingly applied to reserves and are ill-suited to a volunteer environment. Junior non-commissioned officers and above receive an annual Performance Appraisal Report (PAR) designed to provide feedback on their performance and information for promotion decisions. In the ARA the supervisor is required to observe the subject for three months to be eligible to write a PAR. In contrast, a Reserve supervisor is required to report on the subject after seeing the reservist for as little as twenty days; during this time the subject of the PAR may have been on a course or exercise which the supervisor did not attend. The piecemeal nature of Reserve service also prevents supervisors from assigning significant tasks to the subject that would normally comprise the basis of the report. Not only is this an inappropriately applied administrative process, it is often also the closest many members get to a recognition of their individual efforts. Recognition is now considered of profound importance to motivating volunteers.23 The Army periodically recognises members who make an outstanding contribution through awards such as the soldier’s medallion, corps prizes, or unit honours. Those soldiers who attend regularly and perform satisfactorily do not receive particular recognition because ‘they were just doing their job’. This mentality is inadequate for managing volunteers, because it fails to recognise that participating is largely voluntary and an inherently ‘good’ act.

Recruitment

The recruitment of volunteers is fundamentally different to that of employees and the Army Reserve recruitment strategy needs to reflect this. The Army Reserve recruits through the same organisation and generally the same methods as the ARA. Advertising for the Army Reserve in the employment section of newspapers fails to acknowledge that by far the most common method of recruitment to volunteer work is ‘through a friend or relative’. All the advertising combined (including newspapers, community notice boards, newsletters and websites) barely results in half the number of new volunteers as personal contacts.24 This should lead us to conclude that current and former reservists are being under-utilised in the recruitment process. Reservists can be the Army’s avenue for capitalising on professional and social networks. A recruitment strategy that aims to attract volunteers through a friend and relative would better use existing members and would aim to attract groups of friends rather than individuals.

Conclusion: Reserves as Volunteers

An emergency services respondent to Volunteering Australia’s 2009 national survey asserted that:

‘Many valuable vollies leave because the powers that be are trying to turn them into unpaid professionals’25

This could equally apply to many Australian Army reservists. The Defence White Paper 2009 states that there will be further integration of Reserve and Regular components of the ADF.26 During this process we need to be vigilant that we recognise the unique characteristics of Reserve service. Recognising that Reserve service is voluntary will prevent the unthinking transfer of Regular Army strategies onto reservists. The reconception of reservists as volunteers illuminates both dangers and opportunities. If we avoid the dangers and exploit the opportunities we will build a Reserve Army that is made up of members who are simultaneously citizen volunteers and proficient professionals.

Endnotes

1 For example, 103 (Lancastrian Artillery Volunteers) Regiment, Royal Artillery; 3 (Volunteer) Military Intelligence Battalion and 3 (Volunteer) Military Intelligence Battalion.

2 Defence White Paper 2000 – Our Future Defence Force, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2000, p. xii.

3 The Defence White Paper 2009 largely reiterates role of the Reserves and commits the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to ‘better integration between part-time and full-time service in the ADF’. Defence White Paper 2009 – Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2009, p. 90.

4 Defence Act 1903 (Cwlth), s.50D(2). For a more complete and chronological analysis of the see Andrew Davies and Hugh Smith ‘Stepping Up: Part-time Forces and ADF Capability’, Strategic Insights, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Vol. 44, November 2008, p. 4.

5 For a former Chief of Army’s appraisal of Australia’s strategic context in relation to the Army Reserve see Peter Leahy, ‘The Australian Army Reserve: Relevant and Ready’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, p. 11.

6 Davies and Smith, ‘Stepping Up’, p. 14.

7 The figure is even smaller when males are isolated within the data; only 4 per cent of Australian men have more than one job. Productivity Commission, Joanna Abhayaratna, Les Andrews, Hudan Nuch and Troy Podbury, Part Time Employment: The Australian Experience, Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper, Melbourne, June 2008, p. 195, available <http://www.pc.gov.au/research/staff-working/part-time-employment>.

8 It is useful to consider that in many ways the Australian Government does not consider Reserve service work. Reserve salary is not considered work by the Australian Tax Office and is therefore not subject to income tax. Defence does not pay superannuation to reservists unlike all its other workers. Reserve salaries for officer cadets and recruits also often fall below the minimum wage given the number of hours these personnel work.

9 In 2005 there were approximately 220,000 volunteer fire fighters while around in 2008 there were only 19,915 Reservists from all services. R Beatson and J McLennan ‘Australia’s Women Volunteer Fire Fighters: A Literature Review and Research Agenda’, Australian Journal on Volunteering, Vol. 10, 2005, p. 18; Department of Defence ‘Key Questions for Defence in the 21st Century: A Defence Policy Discussion Paper, 2008, p. 41.

10 Volunteering Australia, A Guide for Training Volunteers, Volunteering Australia, Melbourne, 2006, p. 10.

11 A Aitkin ‘Identifying the Key Issues Affecting the Retention of Emergency Services Volunteers’, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Winter 2000, p. 16–23.

12 Defence White Paper 2009 refers to the ‘the significant annual wastage rate among part-time personnel’ as one of the five challenges to the use of Reserves. Defence White Paper 2009, p. 90.

13 Emergency services are Australia’s second largest volunteer sector behind the ‘community/welfare’ sector. Volunteering Australia, National Survey of Volunteering Issues, Volunteering Australia, Melbourne, 2009, p. 6.

14 C Fahey, J Walker and A Sleigh, ‘Training can be a Recruitment and Retention tool for Emergency Service Volunteers’, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2002, p. 3–7.

15 G Lennox, C Fahey and J Walker, ‘Flexible, Focused Training: Keeps Volunteer Ambulance Officers’, Journal of Emergency Primary Care, Vol, 1, Iss. 1–2, 2002.

16 An example of this was detailed in one study that found rural firefighters ‘only want to get on the red trucks and go fight fires with sirens on and lights flashing!: they are not really interested in other activities’. Aitkin, ‘Identifying the Key Issues Affecting the Retention of Emergency Services Volunteers’, p. 17.

17 Volunteering Australia, A Guide for Training Volunteers, p. 2.

18 Ibid., p.13.

19 Volunteering Australia, The National Survey of Volunteering Issues 2011, Melbourne, p. 31, available <http://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/Policy/-National-Survey-of-Volunte…;.

20 Aitkin ‘Identifying the Key Issues Affecting the Retention of Emergency Services Volunteers’, p. 17.

21 Volunteering Australia, ‘National Survey of Volunteering Issues’, pp. 26–27.

22 Aitkin, ‘Identifying the Key Issues Affecting the Retention of Emergency Services Volunteers’, p. 18.

23 Volunteer firefighting literature identifies recognition as one of the four criteria for a successful volunteer organisation. J Snook, J Johnson, D Olsen and J Buckman, Recruiting, Training, and Maintaining Volunteer Fire Fighters, 3rd edition, Missisauga, 2006, p. 91. For more general explanation of why recognition is so important in volunteer organisations see J Esmond, ‘Count On Me! 501 Ideas on Retaining, Recognizing and Rewarding Volunteers’ Newseason Publications, Western Australia, 2005.

24 Volunteering Australia, ‘National Survey of Volunteering Issues’, p. 22.

25 Ibid, p. 12.

26 Defence White Paper 2009, p.90.