Implications for Contemporary Defence Leaders of Air-Land Integration as Part of the Burma Campaign During the Second World War

[I]n Burma our Armies are advancing on the wings of the Allied Air Forces.[1]

Introduction

The campaign in Burma during the Second World War provides an excellent case study of the vital importance of air power to the eventual defeat of a determined adversary. The quote above from Air Chief Marshal Keith Park highlights the interdependence of the land and air forces in Burma. Some have argued that this interdependence was the closest integration between the services achieved in any theatre of war.[2] Air power would not have been able to play its vital role without close integration with the land forces. This close cooperation and integration started from the humblest beginnings and was by no means inevitable. At the start of hostilities with the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), Allied air power in South-East Asia was virtually non-existent.[3] Yet by late 1944 the Commonwealth and American air forces in Burma had participated in one of the war’s most outstanding feats of air support for a land campaign.[4]

I have previously written that the roles of air power were vitally important to an ostensibly land campaign.[5] Air superiority provided the necessary precondition to enable the other roles. There was significant innovation and adaptation in the air mobility role, which provided the solution to the Japanese tactics of encirclement. The strike and reconnaissance role worked in synergy. Air power was vital to the land forces, and its effective use during the campaign was attributable to the development of processes for close integration between the services.

The system or process for organising and executing tactical air support of land operations is now termed air-land integration (ALI). British Army doctrine highlights that ALI requires three key elements: an understanding of each component’s capabilities and limitations, the knowledge of component doctrine and validation through joint training, and the development of strong relationships to engender cooperation and mutual trust.[6]

Henry Probert’s book The Forgotten Air Force is a comprehensive study of air operations in Burma, but it does not identify the challenges of establishing effective ALI.[7] The Forgotten Air Force and other existing literature covers the final mechanisms and organisations for conducting ALI during the Burma Campaign; however, the literature does not discuss how ALI was established. Crucially, because the explanation of the process is missing, the challenges and solutions for effective ALI during this campaign were unknown. My subsequent research has established that there were three key factors that explained the achievement of ALI during the Burma Campaign.[8] The purpose of this essay is to explain why education, external inquiries and receptive commanders were key factors in achieving ALI in Burma. Based on these three key factors, the second purpose is to share the implications of this research for contemporary joint operations.

Key Factor One—Education

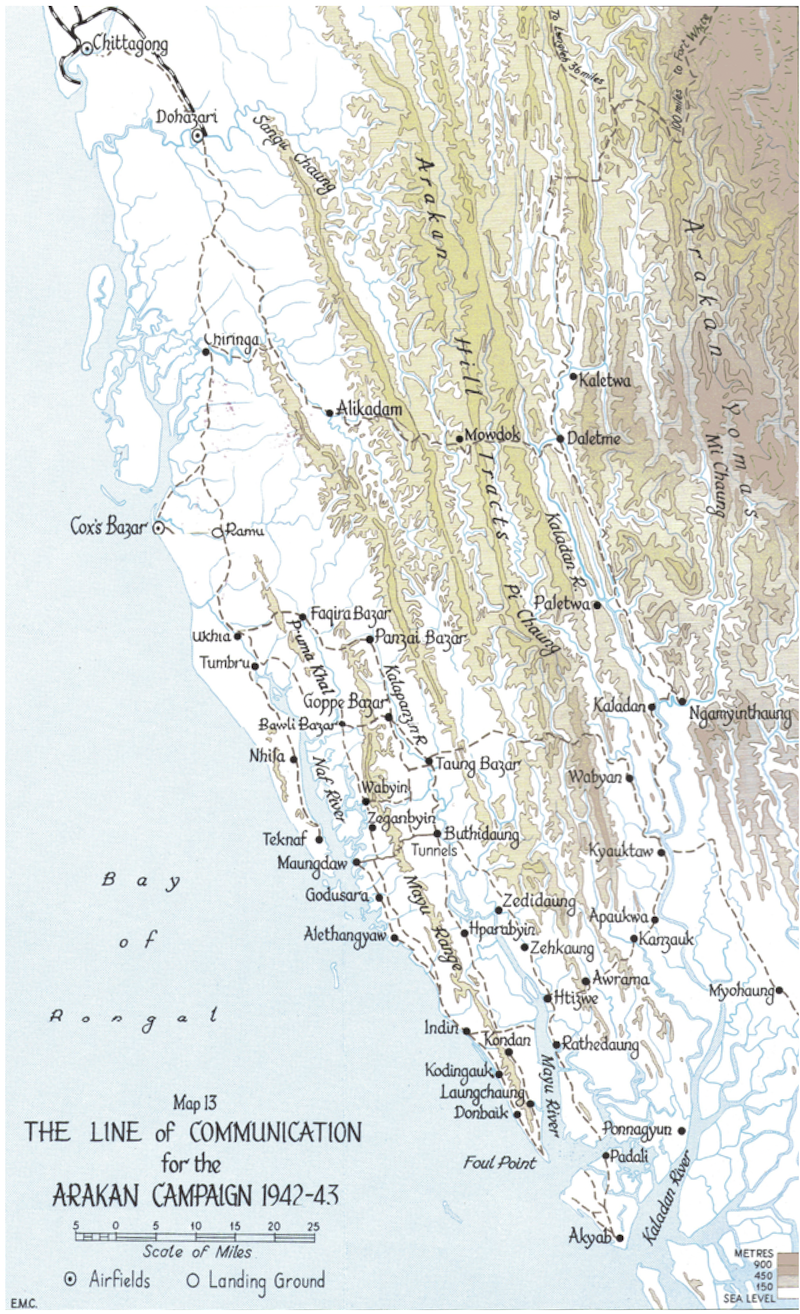

The first key factor in the development of close integration between the services in Burma was the recognition by the RAF that they needed to educate the Army on the capabilities and limitations of air power. This would enable the Army to employ effectively the most powerful weapons in the theatre. The services would not achieve ALI if the Army planned a campaign and then asked the RAF how it could contribute. The RAF identified this requirement for inter-service education from the disappointing results of the First Arakan Campaign (a map is provided at Appendix 1).

During this campaign, Major General Wilfrid Lloyd’s 14th Indian Division was the main tactical formation under the operational command of Eastern Army Headquarters. Lieutenant General William Slim’s XV Corps Headquarters only took operational control towards the end of the campaign on 14 April 1943.[9] For the RAF, Headquarters 224 Group moved from Calcutta to Chittagong on 14 December 1942 for the First Arakan Campaign and cooperated with XV Corps.[10] It was commanded by Air Commodore Alexander Gray, who succeeded Air Commodore Wilson on 2 January 1943.[11]

The campaign commenced on 19 November 1942 and by 17 December, Maungdaw was occupied. Maungdaw, on the west Arakan coast, was important as it provided a secure airfield to co-locate 14th Indian Division Headquarters with 28 Squadron (Tactical Reconnaissance or Tac/R) on 7 January 1943. The 28 Squadron detachment operated about 100 yards from Divisional Headquarters, and ‘no time was wasted in getting information back to Army’.[12]The benefits of this co-location and the development of a habitual relationship are important to the later development of ALI. It was in early January 1943 that the fortunes of the Commonwealth forces started to turn. The Japanese built a defended position a mile north of Donbaik. This position was attacked no fewer than five times from 7 January until the final attempt on 18 March 1943, with the entire strength of 224 Group deployed in close support for the final attack.[13] Each formation attack was a direct frontal assault, with increasing air support, but they were beaten off by the IJA, unmolested in their bunkers.[14]

While there were a number of lessons for the RAF, such as the need for a dedicated close air support (CAS) aircraft type, the most important lesson was the need for joint planning from the inception of the design of a new operation. The early inclusion of the RAF in combined planning was vital to ALI. This was because the relevant Army commanders and staffs needed a thorough education on the importance of the preconditions of air superiority, the need for joint training and the requirement for secure airfields. Prior to the land campaign starting, the RAF needed sufficient time to wrest control of the skies from the Japanese. Only once the RAF had the degree of air control it required could all of the other roles, including reconnaissance, CAS, air transport and heavy bombing, be brought to bear. While the RAF was heavily committed to operations against the enemy air force, joint training would develop the procedures to effectively conduct CAS. Finally, the RAF was a sophisticated organisation with modern but comparatively delicate equipment, operating in one of the most hostile environments in the world. The RAF required secure airfields during the advance to maintain its sophisticated aircraft within effective range of the front. The capture of these airfields was an important requirement. The RAF needed to educate Army senior officers on these requirements, and devised a Senior Army Commanders’ Course.

The Air Force Headquarters (AHQ) India Senior Army Commanders’ Course was supported by the Commander-in-Chief of India, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, and it attracted attendance from across India and Ceylon. The course must have been important to General Headquarters India (GHQ), as it was held at the same time as the First Arakan Campaign was in danger of failing, during the last week of March 1943.[15] Of interest to this essay, attendees included Lieutenant General William Slim as Commander of XV Corps (Eastern Army) and Lieutenant General Philip Christison as Commander of XXXIII Corps (Southern Army), and the course was organised by Group Captain (later Air Commodore) Percy Bernard, 5th Earl of Bandon (shortened to Bandon for the rest of this essay).[16]

This course was important in educating Army officers, as modern doctrine was not yet available in March 1942.[17] The course consisted of a series of lectures on the various aspects of air power and a ‘Subjects for Discussion’ section on Army/Air matters, with topics generated by GHQ and AHQ India. This was clearly the most important part of the course, as a considerable amount of time was allocated to these discussions (almost four hours on the second day) and 17 pages of notes were typed up to provide the context prior to the event. These notes to support the ‘Discussion on Subjects for Discussion on Army/Air Matters’ are illuminating as they clearly set out the important features of air power that the RAF was trying to communicate to the Army.

The ‘Discussion on Subjects’ notes, presented by Air Vice Marshal John Baldwin, the Deputy Air Officer Commander in Chief for India, stressed the importance of achieving air superiority by building the RAF’s strength. Once air superiority was obtained, the RAF would be in a position to turn all its resources to supporting the Army. The ‘by-products’ of gaining air superiority were air defence, indirect air support, CAS, heavy bombing, photographic reconnaissance and tactical air transport.[18] This led to a discussion on the challenges of combined training. The RAF were fully engaged with the enemy air force, with both their bomber and fighter forces. The Army was in the process of rebuilding its forces, and joint training with the RAF was gaining importance with GHQ. While the RAF argued that air operations must come first, they were aware of the ‘heartening effect’ on soldiers of seeing aircraft on exercises. The key to the issue was joint planning. If the officers from the RAF and the Army were involved in planning future operations from the beginning, air formations would be identified to cooperate with Army formations, which in turn would build habitual relationships (such as those between 28 Squadron and 14th Division) and assist with integration. Practical training would allow the shortcomings of Army Staffs in dealing with air power to come to light. As the notes succinctly state, ‘when air staffs and commanders are there in the flesh, and when aircraft are waiting to be used, the issue is forced into prominence’.[19]

The AHQ India Senior Army Commanders’ Course achieved the aims the RAF had set out for it. Senior and influential Army commanders had attended, and the RAF had skilfully educated the attendees on its capabilities and the limitations of air power by stressing the importance of achieving air superiority, conducting combined training, securing airfields and planning all future operations jointly. The next key issue for the development of effective ALI was the arrival of an influential external party with an interest in ALI.

Key Factor Two—External Inquiry Identifies Issue / Internal Committee Fixes Problem

The second key factor in the development of close integration between the services was an influential external party arriving into the theatre at exactly the same time as the retrained, re-equipped land forces were starting their offensive against the IJA in 1944. The 220 Military Mission, headed by Major General John Lethbridge, was dispatched by the British Chiefs of Staff to learn all that was possible about the war against Japan. The ‘Lethbridge Mission’ had already visited the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), where they were deeply impressed by the level of integration achieved by those forces.[20] By coincidence this was the same period in which XV Corps, as part of 14th Army, commenced their offensive against the IJA on the Arakan Coast of Burma. After the Lethbridge Mission visited the XV Corps headquarters, now commanded by Lieutenant General Philip Christison (attendee at the AHQ India Senior Army Commanders’ Course), they observed that the air and land forces ‘were not however, working together as smoothly and as satisfactorily as they were in NEW GUINEA’.[21]

Throughout 1943, efforts to bring Army and RAF commanders together in Burma were encouraged, but at this stage of the campaign, they were not ordered. The initial failures of XV Corps to secure the Razabil position during Operation JONATHAN led Christison or his staff to highlight to the Lethbridge Mission that a lack of artillery and air support was to blame. The lack of co-located commanders, incompatible personalities and friction over the use of tactical and heavy bombing were likely to have been factors in the criticisms made of the air support arrangements. The interview of Christison by the Lethbridge Mission highlighting his concerns was to have profound consequences for ALI in Burma.

A month after the visit to XV Corps Headquarters in the Arakan, Lethbridge had concluded his mission. He presented his observations to Lord Louis Mountbatten as the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (SACSEA) on 28 February 1944.[22] Lethbridge explained that his mission had been impressed by the successes in the South Pacific and South-West Pacific, which he attributed to mastery of the air and sea. He observed that the American fighting services ‘had been welded into one’.[23] Mountbatten picked up on the integration of the American forces and enquired if Lethbridge’s party would ‘suggest any means for achieving greater integration on the land front’. The members of the mission recommended that the commander of the Air Group should be co-located with the commander of the Corps when a battle was in progress. The arrangements between IV Corps and 221 Group were highlighted as satisfactory (this was the relationship between Slim and his counterpart). It was stated that 224 Group’s mobile headquarters was intended to achieve the same effect, but it was not recorded in the minutes what the actual effect was.

Over the next month Lethbridge’s party worked on two reports. The first report, titled 220 Military Mission Report, was published on 25 March 1944 and was 36 pages long.[24] The second report, also titled 220 Military Mission Report, was published in April 1944 and comprised two volumes.[25] It is the first report that is of relevance to this essay (for ease, it will be referred to as the Short Report). At paragraphs 37 and 38 of the Short Report, Lethbridge makes the only critical comments in his entire report; they are based on ALI in Burma. It is worth quoting his comments completely to gain their full context:

With the necessity for, and the advantages of, integration of forces fresh in mind, it was disturbing to find in India an apparent disposition to accept proximity of staffs as adequate substitution for integration of staffs, and it was clear that the degree of unification already achieved by the American forces has not been appreciated. The general impression left on the Mission in respect of the Burma front was that the Army was fighting one war and the Air Force another, and that in consequence much precious effort was going to waste … It was only too evident that on this front the enemy was not being subject to the full impact of the resources in spite of the fine quality of the fighting force. [26]

The phrase ‘acceptance of proximity’ related to the separation of the headquarters of XV Corps and 224 Group by 100 miles, and ‘precious effort going to waste’ related to the perceived lack of use of the RAF’s heavy bombers in support of XV Corps. On 13 April 1944, the Short Report was in front of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) at their 120th meeting. In the minutes for the meeting, reference was made to paragraph 37 of the Short Report and the contrast between the degree of inter-service integration which had been achieved in the Pacific theatre compared with Burma. The report identified that during fighting in the Second Arakan Campaign, 224 Group was charged with the air defence of Calcutta, in addition to the responsibilities of direct support to XV Corps. Even with 221 Group and IV Corps, ‘there was evidence of some lack of cooperation between the two services. This point should be referred to SACSEA for his comment’.[27]

Lord Mountbatten was required by the COSC in London to comment on the Short Report. Mountbatten now needed to determine whether to refute the reports of problems with ALI or to agree with the contents and adapt how his subordinates cooperated with each other.[28] Despite the criticism of his command, Mountbatten chose to agree with the contents of the Short Report and adapt how his Air Force and Army subordinates cooperated, by directing combined planning and co-located headquarters. The interview with Lethbridge and the subsequent correspondence, led Mountbatten to task his staff to comment on the Short Report, in a memorandum to the COSC in London. This task drove two important innovations.

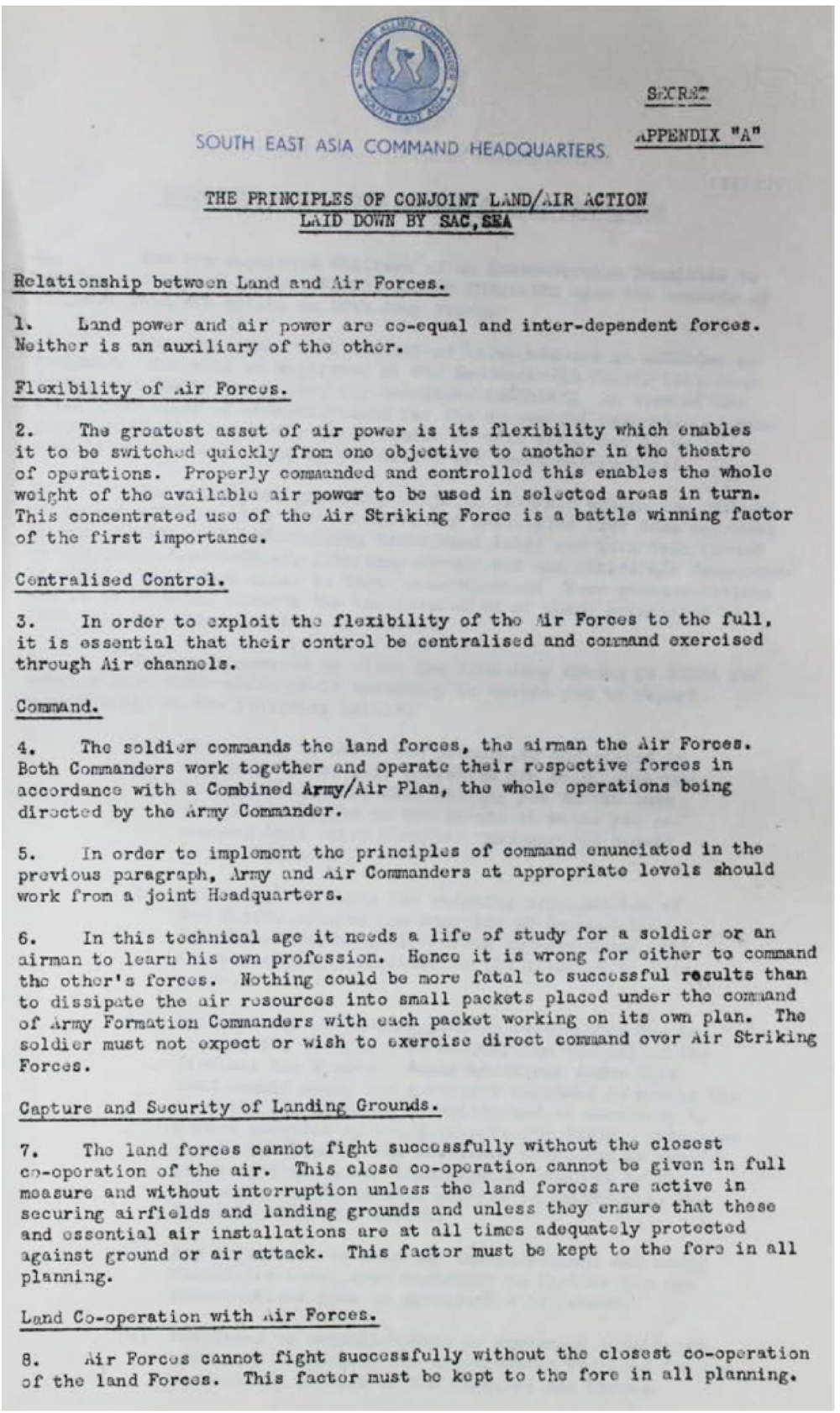

The first important innovation was the issue of The Principles of Conjoint Land/Air Action Approved by the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia in June 1944 (shortened to the Principles).[29] On one page, Mountbatten set out his guidance on ALI. The Principles (see Appendix 2) innovatively used respected evidence from North-West Africa, which included the requirement for joint headquarters and shared responsibility for landing grounds.[30] In essence the Army and the RAF were to be a joint force rather than one supporting the other.[31]

The second important innovation was SACSEA appointing an Inter-Service Committee to examine and report upon the methods of ALI on the 14th Army front, based on the guidance contained within the Principles. Importantly this committee was internal to the organisation, and its observations became recommendations that drove changes that improved ALI. Throughout the process, the committee was interested in identifying improvements to ALI rather than apportioning blame. The committee’s visits were well received by the respective commanders and organisations. This work led to the Memorandum to address the Short Report’s criticisms, which included requests to the COSC for manpower and signals equipment, officers experienced in Joint Composite Group/Army Headquarters, and the machinery of command and control for air supply. The COSC now shared some responsibility for resourcing closer inter-service cooperation in Burma. The impact of the Lethbridge Mission on ALI was not covered in the existing literature, but analysis of the archival material revealed that it was a key factor in the development of close integration between the services. The next key issue for the development of effective ALI was the receptiveness of the relevant commanders to drive integration within their formations.

Key Factor Three—Receptive Commanders Capable of Developing Strong Relationships

The final key factor in improving ALI in Burma was the receptiveness of the tactical commanders to the guidance to drive integration within their formations from late 1944 and their ability to develop strong relationships. The leaders in position in October 1944 had the personalities and experience that enabled their forces to fully embrace ALI. On the Central Front, Lieutenant General William Slim (General Officer Commanding (GOC) 14th Army) was a firm believer in the need for the RAF and the Army to act as one and consistently co-located his headquarters with that of the air commander. He formed a very strong relationship with Air Vice Marshal Stanley Vincent as Air Officer Commanding (AOC) 221 Group. Indeed, by May 1945 the policy produced by the 14th Army / 221 Group Combined Headquarters was adopted by Allied Land Forces South East Asia as the official directive on ALI.[32] On the Arakan Front, Lieutenant General Philip Christison (GOC XV Corps) had been responsible for the observation that air and ground forces were not working smoothly and satisfactorily together that was reported by the Lethbridge Mission; however, by late 1944 he took active steps with his RAF counterpart, Air Commodore Paddy Bandon (AOC 224 Group), to form an integrated headquarters and they also developed a strong relationship.

Christison and Bandon had more obstacles to overcome to achieve effective ALI. Fortunately, Bandon had been responsible for the delivery of the AHQ India Senior Army Commanders’ Course back in 1943 and he had the existing relationship from that course with Christison. Bandon’s appointment in July 1944 gave him five months to sort out the challenges of co-locating two headquarters that were 100 miles apart and up to that point had no experience of working together. The interservice-committee had highlighted that the siting of a combined Corps / Group HQ would require a compromise location further back from the front than the Army Commander would prefer and further forward from the main airfields than the Air Commander would prefer. For the Army commander to maintain his command relationships, he would require the provision of additional communication aircraft.

As a first step, Christison was content to compromise on the location of his headquarters, to allow Bandon to come forward to Shalimar Camp near Cox’s Bazaar. Bandon’s staff had to tackle the twin problems of organising a mobile headquarters that was compatible with that of the Army and of gaining authority for the move. The release of the report of the inter-service committee in October 1944 provided the policy that led to the subsequent authority to form an Advance Headquarters with XV Corps. The joint attack on Letpan by XV Corps / 224 Group demonstrated that their headquarters was capable of managing complex combined operations (see Appendix 3).[33]

The principle that ‘Army and Air Commanders at appropriate levels should work from a joint headquarters’ was at last regarded as an essential element in successful ALI.[34] By the end of December 1944, two joint headquarters had been established: 14th Army / 221 Group, and XV Corps / 224 Group.[35] The Army and especially the RAF had come a long way from the first attempts at ALI in the First Arakan Campaign, when they seemed to be fighting separate wars. Now in Burma, 14th Army and XV Corps were advancing on the wings of 221 Group and 224 Group.[36] The leadership of the Army and Air Force commanders was vital to setting the example of cooperation to their staffs and driving their headquarters together and developing close integration between the services.

Implications for Contemporary Joint Operations

This examination of the three key factors that explain the achievement of ALI as part of the Burma Campaign during the Second World War has validated the key elements of ALI: an understanding of each component’s capabilities and limitations, the knowledge of component doctrine and validation through joint training, and the development of strong relationships. It has also revealed the following implications for contemporary military leaders:

- Have joint doctrine. The Principles set out the senior commander’s requirements for the land and air forces to operate together effectively. These are as relevant today as they were in July 1944.[37]

- Have co-located headquarters. Strong relationships between air force and land commanders spring from a shared understanding of the capabilities and limitations peculiar to their Service. Strong relationships require the commanders to live and work together. Slim understood this important factor and always co-located his headquarters with that of his Air Force counterpart. Christison learned the value of co-location during the Third Arakan Campaign. Importantly, both the land and the air commanders need to be receptive to compromising their headquarters’ location to achieve co-location.

- Conduct joint planning. A co-located headquarters enables joint planning. Joint planning identifies the tasks and the resources required to achieve the respective plans. The early identification of the Army and Air Force resources and of their part in achieving joint objectives allows combined training, the establishment of air superiority and the identification of secure airfields as operational objectives.

- Use external organisations empowered to identify problems and internal organisations to fix them. The Lethbridge Mission was not requested by Mountbatten and, whilst its terms of reference included ‘make recommendations upon which necessary executive decisions can be based’, its main purpose was ‘to look at the effective and economic prosecution of the war against Japan’.[38] However, its observations on the standards of ALI within South East Asia Command were useful for Mountbatten to highlight to his subordinates that there were problems. It would take the internal inter-service committee to find the solutions to the problems.

- Use evidence from other theatres. Mountbatten’s staff were able to develop the Principles in just over two weeks by innovatively adapting doctrine developed during the Mediterranean Campaign to the local environment. The use of quotations from respected commanders such as General Bernard Montgomery and Air Marshal ‘Mary’ Coningham prevented amendments to proven practices.

- Codify revised procedures into doctrine. Every conflict will have its own character, and broad doctrine will not always fit the local circumstances. Procedures will require modification to fit the environment, the enemy and the forces available. All of the commanders identified in this essay codified local arrangements in doctrine.

ALI was not inevitable in Burma during the Second World War. It required each of the key factors to achieve the high degree of interdependence that characterised operations in 1945. The adoption of joint planning, joint principles for integration and co-located headquarters will place future commanders in a better position to face a determined adversary from the start of a future conflict. If for reasons of inter-service friction these recommendations cannot be adopted, external reviews will help commanders identify problems for internal committees to fix. Adaptation of best practice from other theatres or from a recent conflict will provide a timely solution. Once relationships are strong, new procedures will need to be captured in doctrine.

About the Author

Colonel Mark Mankowski has held a range of leadership, operations and training appointments within Australia and overseas. Between 2003 and 2017, he held several operational command appointments in the Middle East. More recently, he commanded elements in support of Operation Bushfire Assist and COVID-19 Assist. Colonel Mankowski holds a Bachelor of Science, majoring in Chemistry, a Master of Arts in Military History and a Master of Military and Defence Studies (Advanced) with Honours. He is currently Colonel Effects at Headquarters 1st Division.

Appendix 1—A Map of the First Arakan Campaign.[39]

Appendix 2—The Principles of Joint Land/Air Action[40]

Appendix 3 – Picture of the Combined Chiefs of Staff[41]

Description

Letpan, Burma, 1945. Some of the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the bridge of the motor launch which took them to the beach-head in the landings by the 15th India Corps at Letpan. They are, left to right: Air Commodore the Earl of Bandon, Commander of No. 224 Group RAF operating on the Arakan front; Lieutenant General F. A. M. Browning, Chief of staff, South East Asia; Lieutenant General A. P. F. Christison, Commander of XV Corps.

Bibliography – Primary Sources

Archives

Australian War Memorial SUK14065. ‘Some of the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the bridge of the motor launch’. Collection Asia:Burma. Accessed May 15, 2021 at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C279683

Imperial War Museum 10516. ‘Letter from General Irwin to General Wavell’. Private Papers of Lieutenant General N M S Irwin CB DSO MC.

The National Archives. CAB 80/86. Serial 735, ‘Army Air Force Integration – Report No. 202 Military Mission’, Memorandum from Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. War Cabinet Chiefs of Staff Committee Memoranda: 230-231. Accessed January 17, 2017 at http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/downloadorder/download?ordernumber=I/140069582206222N&iaid=C387309&reference=CAB%2080/86.

The National Archives AIR 10/5547 Air Publication 3235 Air Support, 1955.

The National Archives Air 20/3593 Lethbridge Mission (220 Military Mission Report).

The National Archive AIR 23/2220 RAF Course for Senior Officers, 1943.

The National Archives AIR 23/4317 220 Military Mission Report Volumes 1 & 2.

The National Archives AIR 23/4318 The Lethbridge Mission and Report on Joint Air/Land Action on the 14th Army Front.

The National Archives AIR 25/942 F540 Operational Record Book for 224 Group, June 01, 1942 – December 1943.

The National Archives AIR 41/36. India Command. Volume 3, September 1939 – November 1943.

The National Archives WO 172/1707 Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (Mountbatten Diaries), February 27 to March 07, 1944.

The National Archives WO 172/1718 Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (Mountbatten Diaries), June 15-23, 1944.

The National Archives WO 178/45 220 Military Mission War Diary, June 11, 1943 –May 22, 1944.

The National Archives WO 202/881 220 Military Mission (Lethbridge) Report, March 1944.

The National Archives WO 202/882 220 Military Mission Report Volume 1, April 1944.

The National Archives WO 202/883 220 Military Mission Report Volume 2, April 1944.

The National Archives WO 203/2419 Army-Air liaison Policy, August 1944 – November 1945.

The National Archives WO 203/3327 Directive AVM Whitworth-Jones and Final Report, 1944.

The National Archives WO 203/5250 Lethbridge Military Mission Report and Comments March – September 1944.

Published

Christison, Philip. The life and Times of General Sir Philip Christison.(Held at the Imperial War Museum: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030004366)

Slim, William. Defeat Into Victory: Battling the Japanese in Burma and India 1942-1945. Cooper Square Press, 2000.

Wavell, Archibald. ‘Operations in India Command, January 1st to June 20th, 1943’. The London Gazette, (38266, 1948).

Bibliography – Secondary Sources

British Army Field Manual. ‘Air Land Integration’, Vol 1 Part 13. December 2009. Accessed January 20, 2016, http://drnet.defence.gov.au/vcdf/JCC/JointForceIntegrationBranch/BattlespaceIntegration/AirSurfaceIntegration-JointFires/Pages/Good-Gouge.aspx.

Kirby, Stanley Woodburn. The War against Japan: India’s Most Dangerous Hour Volume 2: HM Stationery Office, 1957.

Kirby, Stanley Woodburn. The War against Japan: The Decisive Battles Volume 3: HM Stationery Office, 1957.

Kirby, Stanley Woodburn. The War against Japan: The Reconquest of Burma Volume 4: HM Stationery Office, 1957.

Lyman, Robert. Slim, Master of War: Burma and the Birth of Modern Warfare. Constable, 2004.

Mankowski, Mark. An essay on the Success of Air-Land Integration during the Burma Campaign in World War II–An illustration of the importance of leadership, adaptation, innovation, and integration. Australian Army Journal, Spring, Volume XIII, No 2. Accessed February 2017, at https://www.army.gov.au/sites/g/files/net1846/f/aaj_vol13-2_mankowski.pdf

Mankowski, Mark. An essay on What were the Key Factors that explain the Achievement of Air-Land Integration as part of the Burma Campaign during the Second World War, Masters of Military and Defence Studies – Advanced Thesis, Australian National University, 2018

Marston, Daniel P. Phoenix from the Ashes: The Indian Army in the Burma Campaign. Praegar, 2003.

Moreman, Tim. The Jungle, Japanese and the British Commonwealth Armies at War, 1941-45: Fighting Methods, Doctrine and Training for Jungle Warfare. Routledge, 2013.

Orange, Vincent. A Biography of Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park GCG, KBE, MC, DFC, DCL. Methuen, 1984.

Probert, Henry. The Forgotten Air Force: The Royal Air Force in the War against Japan 1941-1945. Brassey’s, London, 1995.

Ritchie, Sebastian. ‘Rising from the Ashes: Allied Air Power and Air Support for the 14th Army in Burma, 1943-1945’, in Peter Dennis & Jeffrey Grey The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943-1944. Chief of Army’s Military History Conference 2003. Accessed January 24, 2016 at http://www.army.gov.au/Our-history/Army-History-Unit/Chief-of-Army-History-Conference/2003-Chief-of-Army-Conference

Us Department of Defense. War Department Field Manual 100-20. Command and Employment of Air Power. 21 July 1943. Accessed August 18, 2018: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/documents/fm100-20_jul_1943.pdf

Endnotes

[1] Vincent Orange, 1984, A Biography of Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park G.C.G., K.B.E., M.C., D.F.C., D.C.L. (Methuen), Chapter 18.

[2] Tim Moreman, 2013, The Jungle, Japanese and the British Commonwealth Armies at War, 1941–45: Fighting Methods, Doctrine and Training for Jungle Warfare (Routledge), 156.

[3] On 7 December 1941, the air strength in Malaya and Singapore amounted to 181 serviceable aircraft. See Henry Probert, 1995 The Forgotten Air Force: The Royal Air Force in the War against Japan 1941–1945 (London: Brassey’s), 35.

[4] Sebastian Ritchie, 2003, ‘Rising from the Ashes: Allied Air Power and Air Support for the 14th Army in Burma, 1943–1945’, in Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey (eds), The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943–1944: The Chief of Army’s Military History Conference (Canberra: Department of Defence), accessed 29 August 2018, at: https://www.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/2003-the_pacific_war_1943-1944_part_1_0.pdf

[5] Mark Mankowski, 2016, ‘An Essay on the Success of Air-Land Integration during the Burma Campaign in World War II—An Illustration of the Importance of Leadership, Adaptation, Innovation, and Integration’, Australian Army Journal XIII, no. 2: 122.

[6] Ministry of Defence, 2017, Army Defence Publication, Land Operations accessed 18 September 2022, at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605298/Army_Field_Manual__AFM__A5_Master_ADP_Interactive_Gov_Web.pdf

[7] Probert, 1995.

[8] Mark Mankowski, 2018, ‘What Were the Key Factors that Explain the Achievement of Air-Land Integration as Part of the Burma Campaign during the Second World War’, Masters of Military and Defence Studies—advanced thesis, Australian National University.

[9] William Slim, 2000 (1956), Defeat Into Victory: Battling the Japanese in Burma and India, 1942–1945 (Cooper Square Press), 158.

The National Archives, AIR 41/36, India Command, Volume 3 (September 1939 – November 1943), 80; The National Archives, AIR 25/942, Operational Record Book 224 Group (1 June 1942 – December 1943); and The National Archives, AIR 10/5547, Air Publication 3235, Air Support (1955), 127. Headquarters 224 Group was formed on 2 March 1942; its original purpose was to control fighter operations in Bengal and Assam. By late 1942 it had responsibility for the light bombers and fighters over the whole of the Burma front from Assam to the Bay of Bengal. It had a number of mobile wings. The order of battle in June 1943 was 165 Wing at Comilla (with Hurricanes from 79 and 146 Squadrons), 166 Wing at Chittagong (with Hurricanes from 67 and 261 Squadrons), 167 Wing at Feni (with Blenheims from 11 Squadron and Bisleys from 113 Squadron) and 169 Wing at Agartala (with Hurricanes from 17 and 27 Squadrons).

[11] The National Archives, AIR 41/36, India Command, Volume 3 (September 1939 – November 1943), Appendix I; and The National Archives, AIR 25/942, Operational Record Book 224 Group (1 June 1942 – December 1943).

[12] The National Archives, AIR 41/36, India Command, Volume 3 (September 1939 – November 1943). The Commander of 14th Division later thanked the Commander of 224 Group for his support and specifically singled out 28 Squadron: ‘I wish to record the effective and whole-hearted co-operation given to this Division [14th Indian Division] by Det 28 Squadron, RAF, in Arakan from December 1942 to April 1943.’

[13] Probert, 1995, 133. Support was provided by three Blenheim Squadrons (direct and indirect support), 28 Squadron (tactical reconnaissance support with Lysanders and then Hurricanes) and 177 Squadron equipped with Beaufighters for long-range indirect support.

[14] Archibald Wavell, ‘Operations in India Command from 01 January to 20 June 43’, The London Gazette, 20 April 1948; Robert Lyman, 2004, Slim, Master of War: Burma and the Birth of Modern Warfare (Robinson), 80–99; Slim, 2000, 147–162; and Daniel Marston, 2003, Phoenix from the Ashes: The Indian Army in the Burma Campaign (London: Praeger), 86–91.

Imperial War Museum, 10516, ‘Letter from Field Marshal Wavell to General Irwin’, Private Papers of Lieutenant General N M S Irwin CB DSO MC (22 March 1943).

[16] The National Archives, AIR 23/2220, RAF Course for Senior Officers (1943). Bandon was promoted to the rank of Air Commodore and appointed AOC 224 Group in mid-1944.

[17] Military Training Pamphlet (MTP) No. 8 was originally published in mid-1942, and it was clear from the First Arakan Campaign and OPERATION Longcloth that adjustments were required. The course notes highlight that a new edition was due to be published in three parts. Part I was to deal with general relations of the Army with the RAF; Part II with direct support, which now required adjustment; and Part III with the RAF on the North-West Frontier. There was also the suggestion of a Part IV on air supply, ‘which is becoming very important’.

[18] The National Archives, AIR 10/5547, Air Publication 3235, Air Support (1955), 26-29. Air Support describes the history of the development of Army Air Support Controls (AASC). The publication also discussed the experiments in ALI led by Army Co-operation Command back in Britain from June 1940 until the middle of 1941. These ‘very vigorous experiments’ led to the first principles and rules for Army air support, which, while amended periodically, remained in place at the time of the course.

[19] The National Archives, AIR 23/2220, RAF Course for Senior Officers (1943).

[20] The National Archives, AIR 23/4317, 220 Military Mission Report Volume 1 (1944), Chapter 2.

[21] The National Archives, AIR 20/3393, Lethbridge Mission (220 Military Mission Report) (April 1944), 87.

[22] The National Archives, WO 172/1707, Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (Mountbatten Diaries, 27 February to 07 March 1944).

The National Archives, WO 203/5250, Lethbridge Military Mission Report and Comments (March–September 1944); and The National Archives, AIR 23/4317, 220 Military Mission Report Volume 1, 25–26. The Lethbridge Mission were so persuaded by the efforts on integration by the American forces that they wrote: ‘it is inconceivable that America, having progressed under the compulsion of war so far along the path to unification of her forces, will at the onset of peace, check and retrogress in response to the demands of petty departmental jealousies’.

[24] The National Archives, WO 202/881, 220 Military Mission (Lethbridge) Report (March 1944).

[25] The National Archives, WO 202/882, 220 Military Mission Report Volume 1 (April 1944); and The National Archives, WO 202/883, 220 Military Mission Report Volume 2 (April 1944).

[26] The National Archives, AIR 23/4318, The Lethbridge Mission and Report on Joint Air/Land Action on the 14th Army Front.

[27] The National Archives, Air 20/3593, Lethbridge Mission (220 Military Mission Report); The National Archives, AIR 23/4318, The Lethbridge Mission and Report on Joint Air/Land Action on the 14th Army Front; and The National Archives, CAB 80/86, Serial 735, ‘Army Air Force Integration’ – Report of No. 202 Military Mission, War Cabinet Chief of Staff Memoranda.

[28] Lethbridge’s experience was not lost to South East Asia Command. He became Slim’s Chief of Staff at Headquarters 14th Army. See Slim, 2000, 374, 387.

[29] The National Archives, WO 172/1718, Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (Mountbatten Diaries, 15–23 June 1944), 171–175.

[30] The National Archives, WO 172/1718, Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia (Mountbatten Diaries, 15–23 June 1944); and The National Archives, WO 203/3327, Directive AVM Whitworth-Jones and Final Report (1944),Enclosure 10. The Principles were derived from Field Manual 100-20, Command and Employment of Air Power, published by the US War Department on 21 July 1943; and Air Power in the Land Battle, issued by the British Chief of the Air Staff.

[31] Stanley Woodburn Kirby, 1965, The War against Japan: Volume IV: The Reconquest of Burma (London: HM Stationery Office), Appendix 2.

[32] The National Archives, WO 203/2419, Army-Air Liaison Policy (August 1944 – November 1945), Enclosure 9A.

[33] Philip Christison, 1986, The Life and Times of General Sir Philip Christison (held at the Imperial War Museum), 156; Slim, 2000, 460–461; Marston, 2003, 179; and Probert, 1995, 256.

[34] See Appendix 2.

[35] The National Archives, AIR 10/5547, Air Publication 3235, Air Support (1955), 133–134.

[36] Orange, 1984, Chapter 18.

[37] See Appendix 2.

[38] The National Archives, AIR 23/4317, 220 Military Mission Report Volumes 1 and 2, 1; and The National Archives, WO 178/45, 220 Military Mission War Diary (11 June 1943 – 22 May 1944), enclosure 12.

[39] Stanley Woodburn Kirby, 1958, The War against Japan: Volume II: India’s Most Dangerous Hour (London: HM Stationery Office), accessed under Open Government licensing arrangements in accordance with https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version…

[40] WO 203/3327, Directive AVM Whitworth-Jones and Final Report (1944), Enclosure 20A; and Kirby, 1965, Appendix 3.

[41] Australian War Memorial, Collection Asia: Burma, accessed May 15, 2021: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C279683