Understanding Defeat

Introduction

Understanding defeat is vital to understanding the Australian Army approach to warfare. Land Warfare Doctrine 1 states that the Army denies and defeats threats to Australia and its interests.[1] While the 2020 Defence Strategic Update modified the terminology somewhat,[2] to defeat an enemy is still central to the Army’s purpose. Yet, despite its importance, doctrine is strangely quiet on exactly what defeat is, and how it relates to other warfighting concepts.

For example, doctrine exhorts commanders and staffs to employ defeat mechanisms, yet does not explain what these mechanisms are or how they go about achieving defeat. Doctrine tells us that we must focus all efforts on the centre of gravity to defeat the enemy, but does not describe the relationship between centre of gravity and defeat. Doctrine tells us to shatter the enemy’s moral and physical cohesion, without explaining what cohesion is or why shattering it is of benefit. It is difficult, therefore, for a commander or planner to reconcile all these concepts to develop a plan that links tactical action on the ground to the enemy’s defeat.

The aim of this article is to provide a framework for defeat. It seeks to fill the gaps in doctrine, provide context, and link disparate concepts into one coherent whole. The article will first look at defeat itself, by defining it in useful terms and discussing its temporary and compounding nature. It will then bridge the gap to defeat mechanisms by introducing the components of defeat, as well as defining the relationship with the centre of gravity. It will conclude by discussing defeat mechanisms, and suggesting a hierarchy for their employment.

Defining Defeat

Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations defines defeat as ‘to diminish the effectiveness of an individual, group or organisation to the extent that it is either unable or unwilling to continue its activities or at least cannot fulfil their intentions’.[3] The US Army provides a similar definition, which is ‘defeat is to render a force incapable of achieving its objectives’.[4] Both of these define defeat in terms of the enemy’s objectives—the enemy is defeated when they cannot accomplish their objectives. However, this is a flawed definition of defeat, as it is not the achievement of the enemy’s objectives that is our concern, but the achievement of our own.

Consider, for example, the fate of the French Maginot Line in World War Two. Built to defend the border with Germany, the Maginot Line was a formidable series of fortifications extending from the Swiss to the Belgian border. However, the Germans wisely avoided this strength, and bypassed the Maginot Line by penetrating through the Ardennes Forrest, encircling the British and French mobile forces in Belgium. The French were forced to capitulate without the Germans having to directly assault the Maginot Line. By the current definition, therefore, the Maginot Line and its garrison remained undefeated, as they remained capable of their mission—defending the German border—until the armistice. By any reasonable standard, however, the Maginot Line was defeated, as it was unable to prevent the Germans from achieving their mission of defeating the French Army.[5] Defining defeat in terms of the enemy’s mission, therefore, is flawed.

US military analyst Brett A Friedman hints at an alternative definition of defeat. In his introduction to tactics, he states:

[W]hatever the mission, the tactician must confront an enemy that will attempt to prevent the accomplishment of that mission. To accomplish the mission, the tactician will have to defeat this opponent in some manner.[6]

This highlights that the current definition of defeat is backwards. Defeating the enemy is not preventing them from achieving their mission; it is preventing them from being able to prevent the success of the friendly mission. Put in the context of a commander or staff developing a plan to achieve a mission, no other definition of defeat makes sense. Why fight an enemy that is not going to prevent you from accomplishing your mission? Why fight an enemy more than is necessary for you to accomplish your mission? Defeat, therefore, might reasonably be defined as ‘to render a force incapable of preventing the success of the friendly mission’.

However, this too is an incomplete definition, as it invites a circular logic trap for missions focused on the enemy. For example, if our mission is to destroy an enemy force, this definition would imply that to defeat this enemy force we must prevent them from being able to prevent us destroying them. While this sounds like a good idea for a skit between General Melchett and Captain Blackadder, it has very little value to the commander or staff. In this case, it is the purpose of the friendly operation that defines defeat, not the mission. For example, our mission might be to destroy the enemy counterattack force for the purpose of preventing interference with an attack by the main body. In this instance, to defeat the counterattack force we must render them incapable of preventing the success of the friendly purpose (a successful attack by the main body). A complete definition of defeat, therefore, is ‘to render a force incapable of preventing the success of the friendly mission or purpose’.

The Temporary and Compounding Nature of Defeat

Before moving on to the components of defeat, it is necessary to explore the temporary and compounding nature of defeat. Firstly, defeat is almost always temporary. The Romans described by Tacitus may have been able to inflict permanent defeat (‘they make a desert, they call it peace’[7]), but that is very rarely the case in the modern world. Given time, any defeated force will regenerate its combat power and capability. A destroyed tank battalion will, given enough time, replace its equipment and personnel casualties. A routed force will, given enough time, regain its cohesion and will to fight. Defeat therefore has a temporal aspect that is often overlooked. When developing a plan to defeat the enemy, it is necessary to appreciate for how long the enemy must be defeated (prevented from interfering with the friendly mission or purpose). This temporal aspect may determine how that defeat is achieved. For example, a destroyed tank battalion will be defeated for longer than a tank battalion that is merely dislocated. As will be discussed again later, this temporal aspect may determine which defeat mechanism is most appropriate.

Secondly, defeat compounds. Small defeats compound into later and larger defeats. This compounding effect occurs both ‘vertically’ and ‘horizontally’. Vertically refers to the idea that defeat compounds upwards from lower levels of command to higher levels of command. Thus, the defeat of a battalion contributes to the defeat of the brigade of which it is a part. This is not to say that every battalion must individually be defeated for the brigade as a whole to be defeated, only that defeat compounds upwards. Horizontally refers to the idea that defeat of the current enemy contributes to the defeat of the next enemy that is fought in sequence.

The Battle of Waterloo provides an example of the compounding nature of defeat. As the battle unfolded, the Allies were successful in a number of actions throughout the day that compounded towards the final defeat of Napoleon. In succession, the Allies were successful in holding Hougoumont, defeating d’Erlon’s infantry attack, defeating Ney’s cavalry attack, capturing Plancenoit and defeating the culminating attack by the Imperial Guard. Each action built on the one that proceeded it towards the final defeat of Napoleon. Thus the defeat of d’Erlon’s infantry attack contributed both to the defeat of Ney’s cavalry attack that followed (compounded horizontally) and to the defeat of Napoleon’s army as a whole (compounded vertically).

The Battle of Waterloo also provides an example of the temporary nature of defeat. In accordance with his tactic of the central position, Napoleon sought first to defeat the Prussian army at Ligny before turning his army to defeat the Anglo-Dutch army at Waterloo. However, due to some indifferent generalship by Grouchy, the Prussians were able to regain their cohesion in time to assist Wellington at Waterloo and were decisive in the defeat of Napoleon. Thus it was Napoleon who was unable to account for the temporary nature of defeat. Napoleon was unable to defeat the Prussians for long enough for his victory at Ligny to compound into victory at Waterloo.[8]

From this we can understand the importance of the control of sequence in war. Indeed, in Fighting by Minutes, Robert Leonhard states that ‘victory in warfare is linked inextricably with the positive control of sequence’.[9] The aim of campaign planning is sequencing successful actions which compound both vertically and horizontally towards the achievement of the strategic goal. However, the gap between the actions must not be such that the enemy defeated in early engagements is able (due to the temporary nature of defeat) to regain their combat power prior to later engagements. This, for example, reinforces the importance of a pursuit following a successful engagement to keep pressure on the enemy during gaps in sequence. Understanding defeat is critical to the control of sequence and tempo.

The Components of Defeat

Now that we understand the meaning of defeat, how do we go about achieving it? Here the discussion normally turns immediately to defeat mechanisms, where, despite significant gaps in modern Australian doctrine, the literature is very rich. However, what is rarely described is exactly how defeat mechanisms achieve defeat. Why does dislocating an enemy lead to their defeat? What about disruption? What is needed is something to explain how those mechanisms work. I will call this ‘something’ the components of defeat.

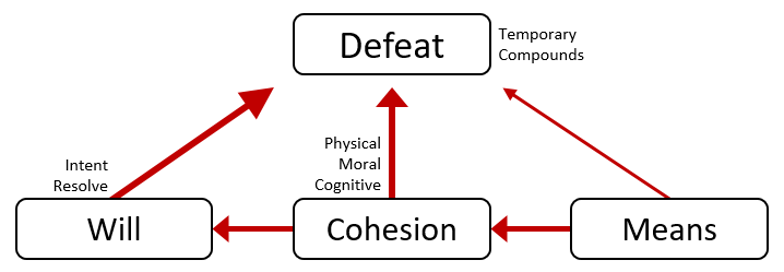

In his discussion of defeat mechanisms, Major Douglas J DeLancey of the US Army provides a starting point. He offers that ‘when an enemy has lost the physical means or the will to fight, he is defeated’.[10] This provides us two components of defeat: means and will. Means is simple to understand. It is the physical resources, such as weapons, vehicles, aircraft and soldiers, needed for the enemy to prevent the success of the friendly mission or purpose. Will is easy to understand in an intuitive sense, but much more difficult to define. A definition of will by Wayne Michael Hall, in his book The Power of Will in International Conflict, runs to 66 words.[11] Helpfully, British Army doctrine states that will has two components: intent and resolve.[12] Intent is thwarted when the enemy no longer believe their aim to be achievable. Resolve is the enemy’s strength of will, which is overcome when they are demoralised and no longer have the desire to continue. Therefore, when the enemy no longer have the means or the will (intent or resolve) to prevent the success of the friendly mission or purpose, they are defeated.

Cohesion

Is there a third component? Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations defines manoeuvre warfare as ‘the shattering, or at least disruption, of the adversary’s cohesion and will to fight, rather than concentrating on destruction of adversary materiel or the holding of territory’.[13] This definition includes both means and will as components of defeat, but also introduces the concept of cohesion. Like defeat, cohesion is a term often used but rarely defined. In fact, in researching this article I was unable to find a single definition of cohesion (used in this context) in any doctrine, book or article. Clearly, however, it is hard to shatter an enemy’s cohesion without knowing what it is. Understanding cohesion, therefore, is vital in understanding defeat.

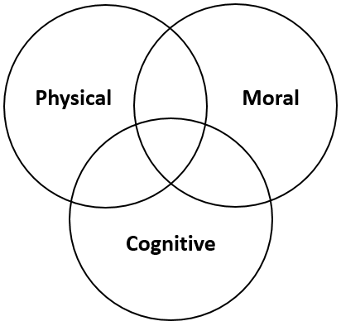

Cohesion can be thought of as the bridge between means and will. Cohesion is what allows an enemy’s will to leverage their means to achieve their desired end. Without cohesion, no matter their strength of will or the capability of their means, an enemy force would have no combat power. Cohesion is what allows combined arms teams to work together, and enables the synchronisation and orchestration of a force. Cohesion is physical, moral and cognitive. Physical cohesion is having the right capabilities at the right place at the right time to achieve the desired effects. For example, an enemy with their artillery out of range of the desired targets would lack physical cohesion. An enemy force that runs out of fuel for their tanks would lack physical cohesion. An enemy with combat forces spread over too great an area to mass decisively would lack physical cohesion.

Moral cohesion is the component most closely linked with the common definition of the word cohesion (‘the act or state of cohering, uniting or sticking together’[14]). It is closely linked to the concepts of both morale and will. Moral cohesion is the force that binds individuals into teams, allows them to withstand adversity and loss, and provides them the imperative to exercise initiative and exploit opportunity. For example, an enemy force that consisted of inexperienced soldiers led by unfamiliar leaders would lack moral cohesion. An enemy force that believed they lacked the support of their home population or did not believe in the righteousness of their cause would lack moral cohesion. By way of illustration, a non-military example of moral cohesion is the ball-tampering scandal involving the Australian men’s cricket team in 2018. After being caught, despite having the same Australian players opposing the same South African players, the Australian team performance dropped significantly. The Australian team were easily defeated as they had lost their moral cohesion.

Cognitive cohesion is related to an enemy’s ability to gather and process information, develop and communicate plans, make timely decisions and adapt to changing circumstances. Essentially, if it happens as part of a staff or inside a command post, it is related to cognitive cohesion. For example, an enemy force that lacked information about the enemy, the terrain, or itself would lack cognitive cohesion. An enemy force that is overwhelmed by information and cannot develop a coherent plan would lack cognitive cohesion. An enemy force that makes poor decisions, late decisions, or no decisions at all would lack cognitive cohesion. The popular expression to ‘get inside the enemy’s OODA loop’[15] is an example of attempting to degrade cognitive cohesion.

All the elements of cohesion overlap and interrelate, as shown in Figure 1 below. A lack of cognitive cohesion, with a force unable to develop a coherent plan, may result in a lack of physical cohesion, with the force not having the right capabilities at the right place at the right time to be effective. This lack of cognitive and physical cohesion may lead to a lack of moral cohesion, with soldiers losing confidence in their leadership and the effectiveness of their team.

Figure 1. The overlapping and interrelated nature of cohesion

All that remains in discussing cohesion, therefore, is to propose a definition. Noting how broad and intangible the concept is, this is very difficult (which is perhaps why it is not defined elsewhere). However, the aim of the article requires that at least an attempt be made. Therefore a proposed definition is:

Cohesion is the largely intangible factor that enables a force to employ its physical strength to achieve its desired end. It is necessary for the different components of a force to work in a coordinated manner towards a common goal. Cohesion has physical, moral and cognitive components. Degrading cohesion degrades combat power; increasing cohesion increases combat power.[16]

Why Not Just Defeat Will?

Manoeuvre theory is the Australian Army’s philosophical approach to warfare, and defeating will is central to this philosophy. Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power states that manoeuvre’s ‘essence lies in defeating the enemy’s will to fight … rather than destroying his forces’,[17] adding that ‘the primary objective of manoeuvre is to defeat the enemy’s will to fight’.[18] Why then are there three components of defeat? Why do we not focus all efforts on defeating the enemy’s will alone? There are a number of reasons. Firstly, it is difficult to distinguish what to attack to influence will directly. For example, it is extraordinarily difficult, particularly at the tactical level, to identify a centre of gravity that undermines the enemy’s will to fight. Most attempts to do so lead to an ephemeral, intangible centre of gravity from which meaningful critical vulnerabilities cannot be derived.[19] If, as the tenet requires, we focus all actions on the centre of gravity, how can we attack will directly if we cannot make it the focus of the centre of gravity construct?

Secondly, attacking will directly often requires capabilities and assets that do not exist at all levels of command, and the use of these assets often requires more time and command authority than the circumstances allow. For example, information operations are often cited as a means of attacking will,[20] yet most levels of command do not have the capability to wage effective information operations and do not have the ability to measure the effectiveness of information operations; nor do their missions provide enough time for information operations to be decisive.

Thirdly, the enemy’s will, and the threshold at which it will break, is difficult to quantify, which can lead to miscalculation. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine provides a recent example. On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine over a wide frontage, from Kyiv in the north to Kherson in the south. The invasion force sacrificed security to facilitate a rapid penetration to points of strategic and political significance. Large-scale air and missile attacks, on targets throughout the length and breadth of Ukraine, were combined with the invasion. While it is perhaps too early to make concrete conclusions, it is likely that the Russians intended this sudden and massive attack to quickly break the Ukrainian will to resist. The Russians can perhaps be forgiven for their hubris, as even Western intelligence agencies expected Ukraine to capitulate in a matter of days. However, as we now know, the Ukrainian will was not broken and they ferociously defended their nation. The Russian invasion force, optimised as it was for a ‘shock and awe’ style attack, was not prepared for a prolonged campaign. The Ukrainians were therefore able to inflict significant defeats on the Russian forces, which simultaneously undermined the Russian and bolstered the Ukrainian will to fight. The initial Russian invasion failed—all due to a miscalculation as to the will of the Ukrainians.[21]

If it is difficult to attack will directly, it may be attacked indirectly. How to do this? Will can be attacked indirectly by attacking the other components of defeat—means and cohesion. This is because there is a relationship between means, cohesion and will. Degrading cohesion also degrades will. Degrading means degrades both cohesion and will. For example, we might choose to attack an enemy tank company (a component of their means), which forms the counterattack force as part of their defensive plan. Destroying this counterattack force will degrade the enemy’s physical cohesion, as a key capability is no longer in the correct place at the correct time. Cognitive cohesion will also be degraded, as the defensive plan is no longer appropriate and will have to be quickly adapted by the commander and staff. This reduction in means and degradation of cohesion will also result in a reduction of the defenders’ will to fight. Knowing there is no longer a counterattack force coming to aid them if they become decisively engaged, they will be more likely to break from their positions rather than continue to fight.

To sum up this section, means, cohesion and will are what the enemy needs to be able to prevent the success of the friendly plan or purpose. Therefore means, cohesion and will are the components of defeat. Remove one and the enemy is defeated. Defeating will is the preferred method to achieve defeat; however, attacking will directly is difficult. Therefore, will must often be attacked indirectly, through attacking means and cohesion. In this framework, all actions to defeat the enemy are aimed ultimately at defeating will, thus aligning with manoeuvre theory. This framework is illustrated in Figure 2 below. The size of the arrows represents the strength of the relationship between the components.

Figure 2. The components of defeat

Relationship with Centre of Gravity

The tenets of manoeuvre direct us to focus all actions on the enemy’s centre of gravity. However, what doctrine does not tell us is how focusing all actions on the enemy’s centre of gravity leads to their defeat. It is outside the scope of this article to discuss centre of gravity theory in detail; however, it is necessary to define the relationship between centre of gravity and defeat. To do this we will use the description of centre of gravity provided in legacy doctrine. While more recent joint doctrine has refined the description, the legacy description better illustrates the relationship with the framework for defeat.

Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power defines centre of gravity as the ‘characteristics, capabilities or localities from which a nation, an alliance, a military force or other grouping derives its freedom of action, physical strength or will to fight’.[22] This definition has a nice symmetry with the components of defeat previously discussed (means, cohesion and will). Physical strength is an obvious analogue of means, and will to fight speaks for itself. Freedom of action, in this context, can be thought of as the practical expression of cohesion. A force with cohesion has freedom of action; a force without freedom of action lacks cohesion. The centre of gravity construct, therefore, tells us what characteristics, capabilities or localities provides the enemy the means, cohesion and will to prevent the success of the friendly plan. Thus, the critical vulnerabilities identified in the centre of gravity construct tell us what to target to defeat the enemy’s means, cohesion and will.

This is the link between the centre of gravity and defeat, and why focusing all actions on the enemy centre of gravity leads to their defeat. The centre of gravity analysis quantifies the components of means, cohesion and will such that they can be precisely targeted. From this we can also understand more about the centre of gravity construct itself, and that not all critical vulnerabilities are created equal. For example, we know that degrading will is the preferred approach to defeating the enemy. Therefore, when identifying vulnerabilities, we should first seek to identify those that undermine the enemy’s will. We should next seek to identify vulnerabilities that undermine the enemy’s cohesion. Only then should we look for vulnerabilities that undermine the enemy’s means. Such a prioritisation better enables us to identify the best mechanism to quickly defeat the enemy.

Defeat Mechanisms

Now that we understand the components of defeat, we can turn our attention to defeat mechanisms themselves. Unhelpfully, Australian doctrine does not provide a definition of defeat mechanism. In its place, the US Army definition will suffice: ‘the method through which friendly forces accomplish their mission against enemy opposition’.[23] This definition nests nicely with the definition of defeat proposed in this article as it frames defeat mechanisms in terms of the accomplishment of the friendly mission. As previously discussed, the centre of gravity construct tells us what to attack to degrade the enemy’s means, cohesion or will. The defeat mechanism provides us the how—that is, the mechanism by which we attack critical vulnerabilities to degrade means, cohesion or will to defeat the enemy. It is with defeat mechanisms that the intellectual framework so far described turns into physical action on the ground.

There is no one accepted list of defeat mechanisms. Leonhard gives us pre-emption, dislocation and disruption.[24] US Army doctrine gives us destruction, dislocation, disintegration and isolation.[25] Delbruck gives us annihilation and exhaustion.[26] British Army doctrine gives us surprise, pre-emption, dislocation, disruption and destruction.[27] Wass de Czege gives us attrition, dislocation and disintegration.[28] Australian Army doctrine does not contain a list of defeat mechanisms; however, various parts of doctrine refers to pre-emption, dislocation, disruption and destruction.[29] There is no need for a definitive list of defeat mechanisms, as it would artificially limit creativity. However, it is the defeat mechanisms of pre-emption, dislocation, disruption and destruction that will be explored here.

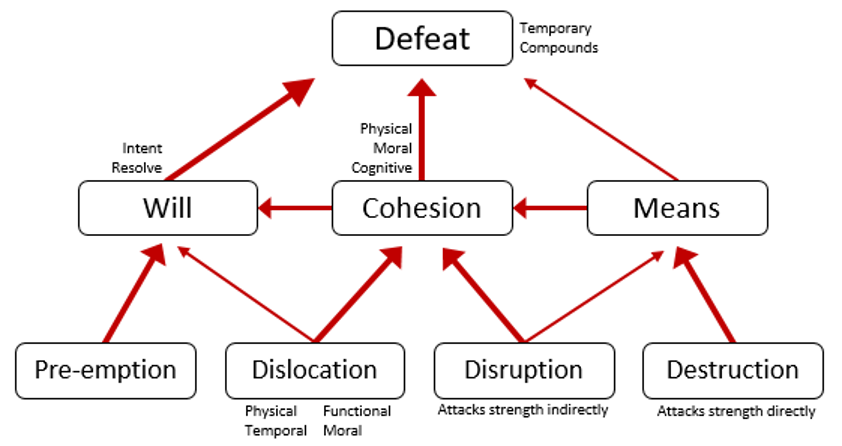

Pre-emption is the first and most powerful defeat mechanism. Pre-emption is acting before the enemy to seize or remove an opportunity. Thus, possible enemy courses of action are negated as they no longer have the opportunity to implement them. Pre-emption can be considered a special category of defeat mechanism, as successful pre-emption does not so much defeat the enemy as make defeat unnecessary. However, relating pre-emption back to the categories of defeat, we can say that pre-emption is aimed at defeating will. Specifically, it targets the intent component of will, as the enemy will believe their aim to be no longer achievable. This is why pre-emption is the most powerful defeat mechanism—it is the one that acts most directly on defeating the enemy’s will.

Dislocation is the second defeat mechanism. Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations defines dislocation as ‘action to render an adversary’s strength irrelevant’.[30] Leonhard identifies four types of dislocation—positional, temporal, functional and moral.[31] The types of dislocation (with positional dislocation changed to physical dislocation) were defined in obsolete versions of doctrine, but do not appear in current versions.[32] However, physical dislocation is causing the enemy strength to be in the wrong place. This can be achieved by moving the enemy strength away from the decisive point, or by moving the decisive point away from the enemy strength. Temporal dislocation is manipulating time and tempo such that the enemy cannot bring their strength to bear in time. Temporal dislocation is what powers the principle of war of surprise. Functional dislocation is causing the enemy to have the wrong type of strength for the current problem. Obliging the enemy to fight a mobile campaign with dismounted forces would be an example of functional dislocation. Moral dislocation is exploiting a force’s ethics, laws and political considerations such that they cannot employ their strength. Operating from an area filled with non-combatants, knowing that rules of engagement will prevent effective fire, is an example of moral dislocation.

Linking dislocation back to the components of defeat, dislocation primarily targets the enemy’s cohesion. It does not take a great leap of imagination to understand that physically dislocating the enemy leads to degrading physical cohesion, or that morally dislocating the enemy leads to degrading moral cohesion. Essentially, dislocation denies the enemy the physical, moral or cognitive cohesion needed to employ their strength effectively. As dislocation does not involve a direct attack it does not have any effect on means (which is what distinguishes it from disruption, discussed next). However, dislocation, particularly moral dislocation, also has some small effect directly against the enemy’s will.

Disruption and destruction are similar and will be tackled together. Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations defines disruption as ‘a direct attack that neutralises or selectively destroys key elements of the adversary’s capabilities’.[33] It defines destruction as ‘sufficient damage of an enemy state or non-state adversary that it is unable to return to conflict’.[34] Disruption and destruction can be confused as they both involve a direct attack. What then is the difference?

The key difference is that destruction attacks the enemy’s strength directly, while disruption attacks the enemy’s strength indirectly through vulnerabilities. For example, we might identify an enemy strength to be their tank company. Destruction would attack this strength directly. This would see the tanks themselves targeted and destroyed. Disruption would attack this strength indirectly by targeting the vulnerabilities identified for that tank company. For example, we might destroy command links to prevent the tank company from receiving coherent orders. We might destroy fuel trucks to prevent the tanks from being able to manoeuvre. We might destroy ground-based air defence assets so that the enemy commander will not deploy the tanks, fearing air attack. Clearly, disruption is reliant on having completed a centre of gravity analysis to determine vulnerabilities.

Destruction, then, works entirely against the component of means. Destruction takes away from the enemy the means to interfere with the friendly plan. Disruption, on the other hand, works primarily against the component of cohesion. Disruption attacks those things that are needed for the enemy to employ their means. Put another way, disruption attacks those things that provide the enemy force its cohesion. Disruption has no effect directly against the enemy’s will. However, as disruption involves a direct attack, it also has some effect on the enemy’s means.

To summarise, defeat mechanisms are the method (the how) by which we target identified vulnerabilities (the what) to degrade the components (means, cohesion and will) to defeat the enemy. The defeat mechanisms explored here are pre-emption, dislocation, disruption and destruction. Pre-emption works entirely against will, dislocation primarily against cohesion and secondly against will, disruption primarily against cohesion and secondly against means, and destruction entirely against means. Figure 3 below illustrates the complete framework for defeat. The size of the arrows represents the strength of the relationship.

Figure 3. The completed framework for defeat

Is Destruction a Defeat Mechanism?

Destruction is often rejected as a defeat mechanism, either because it is viewed only as an effect that contributes to the other defeat mechanisms, or because it is viewed as inherently attritionist in nature, which is the antithesis of manoeuvre warfare. However, any framework for defeat must include destruction as a defeat mechanism to be complete and have practical value in application. The current definition of disruption (‘a direct attack that neutralises or selectively destroys key elements of the adversary’s capabilities’) requires that for disruption to be applied at a higher echelon, destruction will likely have to be applied at a lower echelon. For example, for a brigade to apply disruption as a defeat mechanism, they will likely have to task a battalion to destroy something. The battalion, therefore, will likely employ destruction as a defeat mechanism to achieve their mission. Not including destruction as a defeat mechanism would imply that we would never seek to destroy an enemy strength, at any echelon. While this might sound appropriate to the theoretician, such a framework would have very little value to the practitioner who must work within the practical realities of the battlefield.

In addition, under this framework for defeat, we use the mechanism of destruction not only to destroy the enemy’s means but ultimately to defeat their will. British Army doctrine lays this out clearly: ‘attacking and destroying physical capabilities is therefore required by the manoeuvrist approach as a means to an end of defeating the enemy’s will to fight’.[35] Thus, destruction is not inherently attritionist in nature and is a necessary part of manoeuvre warfare.

Is There a Hierarchy of Defeat Mechanisms?

Is there a hierarchy of defeat mechanisms? Should we prefer to use one rather than the others? Leonhard provides the hierarchy as pre-emption, dislocation, and disruption.[36] In accordance with the previous section, we can add destruction to this hierarchy after disruption. Based on the framework so far established, this order intuitively makes sense. If the primary objective of manoeuvre is to break the enemy’s will, we should therefore prefer the mechanisms that attack will the most directly. Logically, Leonhard’s order (with destruction added) makes sense. As pre-emption acts only against will, it is the most preferred. As destruction attacks will the most indirectly, it is the least preferred.

However, there is another way to look at the hierarchy of defeat mechanisms. Earlier it was identified that defeat is temporary and that defeat compounds. Much of the art of war is sequencing actions to compound defeat both horizontally and vertically, without providing the enemy the time to recover from their defeats. However, every action against the enemy costs resources. Those resources could be fuel, time, casualties or political will. Any resources expended now at the current enemy cannot be expended later at the next one. Therefore, we should seek to defeat the enemy with the least expenditure of resources, to retain as many resources as possible for the next action in sequence. Defeat mechanisms, therefore, should be preferred based on their efficiency—the amount of resources needed to be successful.

Using this logic, the order suggested by Leonhard cannot be the answer in all circumstances, as the most efficient defeat mechanism will change based on the circumstances of the mission. It was established earlier that defeat is temporary and that, when developing a plan, commanders and staffs must appreciate for how long the enemy must be defeated for them to achieve their mission. This temporal factor might determine which is the most efficient defeat mechanism. Revisiting the earlier example, a destroyed tank battalion will be defeated for longer than a tank battalion that is merely dislocated. In this instance, destroying the tank battalion may require less resources than seeking to keep the battalion dislocated for the entire length of the mission. In that instance, destruction might be the most efficient defeat mechanism and therefore the most preferred. Whatever the circumstances of the mission, it is vital to employ defeat mechanisms based on their efficiency, as this is what enables us to better control sequence in war.

Conclusion

Understanding defeat is vital to understanding the Australian Army approach to warfare. Yet current Army doctrine does not define defeat, or the component and mechanisms that achieve defeat, in a useful way that aids this understanding. This is a recent oversight, as legacy doctrine did include adequate descriptions of many of these concepts. This article has proposed a framework for defeat that fills these gaps in doctrine and links disparate concepts into one coherent whole.

It is recommended that Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power be updated to include a framework for defeat that defines and describes the concepts and terms discussed in this article. In addition, subordinate doctrine, such as Land Warfare Doctrine 3-0-3: Formation Tactics,should be updated to include how tactical tasks and techniques support the achievement of defeat mechanisms and thus contribute ultimately to the enemy’s defeat. Such an update would provide commanders and staffs the intellectual framework to develop plans that link tactical action on the ground to the enemy’s defeat, thus fulfilling the Army’s purpose.

About the Author

Major Mark Sargent is a Cavalry officer, with regimental service at the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and B Squadron 3rd/4th Cavalry Regiment, in addition to numerous training appointments in Australia and the United States. He has operational experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. Major Sargent is currently the Officer Instructor – Armour at Combat Command Wing, Combined Arms Training Centre.

Endnotes

[1] Australian Army, 2017, Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia), 19.

[2] The 2020 Defence Strategic Update states three new defence objectives—to shape Australia’s strategic environment; to deter actions against Australia’s interests; and to respond with credible military force, when required. Implied in responding with credible military force is the need to defeat adversaries. Department of Defence, 2020, 2020 Defence Strategic Update (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia), 25.

[3] Poor syntax in the original. Department of Defence, 2021, Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations (Canberra: Australian Defence Force), 117.

[4] Department of the Army, 2019, Army Doctrine Publication 3-0: Operations (Washington DC: Department of the Army), 2-4.

[5] This paragraph is drawn from Robert A Doughty, 2014, The Breaking Point: Sedan and the Fall of France, 1940 (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books).

[6] Brett A Friedman, 2017, On Tactics (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press), 16.

[7] Cornelius Tacitus, 2015, The Germany and the Agricola of Tacitus: The Oxford Translation Revised, with Notes (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform).

[8] These two paragraphs are drawn from Gordon Corrigan, 2014, Waterloo: A New History (New York: Pegasus Books).

[9] Robert R Leonhard, 2017, Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (independently published), 130.

[10] DJ DeLancey, 2001, Adopting the Brigadier General (Retired) Huba Wass de Czege Model of Defeat Mechanisms Based on Historical Evidence and Current Need (Fort Leavenworth: School of Advanced Military Studies), 10.

[11] ‘The appearance of one’s desire, volition, life force—empowered by potency of resolve and willingness to sacrifice, that when yoked with strength of motive and appropriate capabilities, provides action sufficient to accomplish or satisfy an aim, goal, objective, strategy and thereby imposing one’s desires over and gaining the acquiescence of a resisting entity or understanding the phenomenon sufficiently to resist such attempts from another human entity.’ Wayne Michael Hall, 2018, The Power of Will in International Conflict (Praeger Security International).

[12] British Ministry of Defence, 2017, Army Doctrine Publication: Land Operations (Warminster: Ministry of Defence), 5-4.

[13] Department of Defence, 2021, 12.

[14] Macquarie Dictionary Online, 2021, Macquarie Dictionary Publishers.

[15] Observe, Orient, Decide, Act—a decision cycle developed by military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd.

[16] There is an interesting parallel between the elements of cohesion (physical, cognitive and moral) and the components of fighting power (physical, intellectual and moral).

[17] Australian Army, 2017, 31.

[18] Ibid. 33.

[19] Aaron P Jackson, 2017, ‘Center of Gravity Analysis “Down Under”: The Australian Defence Force’s New Approach’, Joint Force Quarterly 84: 84.

[20] Information operations: ‘The operational level planning and execution of integrated, coordinated and synchronised kinetic and non-kinetic actions against the capability, will and understanding of target systems.’ There is a symmetry between this definition and the components of defeat. Department of Defence, 2016, Australian Defence Force Publication 3.13.1: Information Operations Procedures (Canberra: Australian Defence Force), 1-3.

[21] This paragraph is drawn from Brian M Jenkins, ‘The Will to Fight, Lessons from Ukraine’, The RAND Blog, Rand Corporation, 29 March 2022.

[22] Australian Army, 2017, 34.

[23] Department of the Army, 2019, 2-4.

[24] Robert R Leonhard, 1991, The Art of Maneuver (New York: Ballantine Books), 61.

[25] Department of the Army, 2019, 2-4.

[26] Hans Delbruck, 1985, History of the Art of War within the Framework of Political History IV (Westport: Greenwood Press).

[27] British Ministry of Defence, 2017, 5-4.

[28] De Lancey, 2001, 20.

[29] Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power lists dislocation, disruption and destruction as means of defeating the enemy’s centre of gravity. Australian Defence Force Publication 3.0: Campaigns and Operations includes pre-emption as an effect that can be generated at the operational level. While neither document refers specifically to defeat mechanisms, the terms are used in that context.

[30] Department of Defence, 2021, 75.

[31] Robert R Leonhard, 1998, The Principles of War for the Information Age (Novato: Presidio Press), 65.

[32] Australian Army, 2002, Land Warfare Doctrine 1: The Fundamentals of Land Power (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia), 69.

[33] Department of Defence, 2021, 75.

[34] Ibid., 117.

[35] British Ministry of Defence, 2017, 5-4.

[36] Leonhard, 1991, 79–80.