‘No Other System Could Have Achieved the Result’

Australian Beach Groups, 1943-1945

The process of getting men and vehicles ashore during an assault landing and maintaining them at their full fighting efficiency is complicated by the very nature of the operation … it is no exaggeration to say that once a beach head has been secured, the success of the operation will depend very largely on the early establishment and smooth running of an efficient beach organisation.[i]

Introduction and Context

By 1943, the American and Australian forces had gained the initiative against the Japanese in New Guinea, and General Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA) went on the offensive. In broad terms, he wished to leapfrog along the northern coast of New Guinea, capturing footholds from which to launch subsequent air and amphibious attacks on increasingly isolated Japanese positions. These subordinate operations were part of the larger one—Operation Cartwheel—whose goal was to isolate and reduce the pivotal Japanese garrison on Rabaul. One such subordinate attack was Operation Postern in September 1943. It combined an amphibious landing near Lae with a flanking parachute drop and air landing at Nadzab. While it achieved its objective, the amphibious landing conducted by the 9th Australian Division generated many lessons relating to logistics and management of an amphibious beachhead. The planned scheme of manoeuvre, wherein the Australians would be carried and landed by American vessels, was influenced by the general lack of amphibious ships and landing craft available to the SWPA at that time. However, several of these lessons pertained to the compressed training and preparation time that had been available before the landing. For example, there had been limited opportunity to train with the 2nd Engineering Special Brigade (2 ESB) (the specialist United States Army amphibious force that provided the smaller landing craft in the ship-to-shore connector role) as well as the troops allocated the tasks of onshore stevedoring and beach management.[ii] There were other key issues identified during and after Operation Postern. Foremost was the gross miscalculation of logistics requirements within the beachhead and a general lack of experience in amphibious logistical planning.[iii] This resulted in the diversion of fighting battalions from operational tasks to the beachhead, where they acted as labour to unload stores and equipment from the landed craft. Further, poor layout and management of the beachhead and beach maintenance area (BMA) resulted in crowded, unprotected and misplaced stores.[iv]

The BMA was a linchpin in any amphibious operation. This was the term given to the beaches developed for landing and the logistical area immediately inland of the shore. Here beach groups established stores dumps, workshops, and transit areas to maintain the formations and units in the forward area and to maintain a steady flow of traffic through the beaches. Operation Postern highlighted the need for clear and unified responsibility for the beachhead. For that landing, the 9th Australian Division with some attached units (most notably elements of 2 ESB) was responsible for the beachhead and later the BMA, all the while trying to push inland and fight to its objective. The integration of 2 ESB into 9th Division’s command structure did not result from a desire to keep a key logistic element ‘in house’ but was instead born of a misunderstanding about the role of a divisional headquarters in such landing operations. As a result, responsibilities (and therefore command authorities) were not well understood or specified by the divisional headquarters, resulting in mismanagement at the beachhead. For example, 2 ESB would be responsible for aspects such as beach signage, organisation of the beach, control of landings, unloading of craft and handling of labour—including attached Australian pioneers assigned to this task. The divisional deputy assistant quartermaster-general (DAQMG) was responsible for the design of the ‘key plan’ (the planned layout of the BMA) but also had ongoing supply responsibilities once the division was ashore. The divisional chief Royal Engineers (CRE—senior engineer planner) was responsible for beach exits, which were a fundamental part of the key plan, but the ESB would actually do the engineering work with Australian plant operators attached.[v] It was a less than ideal situation leading one post-landing analysis to observe that ‘beach organisation and unloading must be under control of one officer who should not be concerned with other administrative functions’.[vi]

Many of the issues with beachhead management had been already identified in the amphibious training prior to Postern. These too may be grouped into matters of command and control, sufficiency of troops to task, planning considerations around the layout of a BMA, and general familiarity with the demands and nuances of amphibious operations. For example, one report on the exercises conducted by the 6th Australian Division in August 1943 noted ‘poor organisation of labour’, ‘slow discharge of stores and personnel’, ‘absence of flank protection on the actual beach’, ‘absence of any markings on beach to indicate areas searched and cleared of mines’ and ‘congestion on the beach’.[vii] Likewise, the 9th Division, in a pre-Postern training report, recorded that it needed more time to operate with 2 ESB. It noted that the ‘pioneer battalion complete has not functioned in conjunction with [2 ESB] Shore Battalion’ and that Australian engineers ‘have not participated in construction of Maintenance Area’ and ‘have not trained with this unit [2 ESB]—always dets replaced by other units. Hence liaison by essential personalities not made’.[viii] After the landing, the 9th Division identified that the current system—essentially grafting several attached Australian and US units onto the division—was no longer fit for purpose. In response, it recommended:

[A] Beach Group … should be so formed that it contains units of all the services and should … provide local protection from within its own resources. Shortly after D-Day it should be responsible for all reception and holding in the beach maintenance area, for forward distribution as far as the divisional rear dump area and for evacuation to and from the beach and beach maintenance area.[ix]

Importantly the beach group did not remove the fighting division’s need to undertake logistical planning or conduct the normal logistical replenishments of its units once ashore. Instead, the beach group was an interface to help a landed force transition from sea to land:

The interposition of a beach organisation into the normal system of maintenance in the field should not create any special difficulties. The only difference between a landing operation and land warfare is that Beach Group commander has been given an organisation with which to shoulder the responsibility of ensuring the smooth delivery of the force and its requirements from ships and craft to suitably prepared transit areas and dumps.[x]

Thus exercises and operations conducted in 1943 illustrated that the Australian Army was deficient in certain logistics and command and control functions, hindering it from becoming a fit-for-purpose amphibious organisation. One such deficiency was the management of the beachhead during the landing and initial breakout stages, along with conduct of all aspects of logistics to, from and through the beachhead and beach maintenance area, linking the fighting formations ashore with their seaborne support. In response—and absorbing the British experience from the North Africa and Sicily landings—the Australian Army created the 1st and 2nd Australian Beach Groups in late 1943 and early 1944. These units would be instrumental in 1945 when the 7th and 9th Australian Divisions conducted three large-scale amphibious landings in Borneo as part of the Oboe operations.[xi]

The Response—Organisation, Training and Doctrine of the Australian Beach Groups

The Army’s response to the recommendations of the Operation Postern after-action report was swift. The exact timeline of events between the report’s submission and the decision to raise a beach group is unclear; to date the author has not been able to find an executive document ordering the beach groups’ formation. Indeed, it is entirely possible that the decision to create a beach group was made before or concurrent with Operation Postern. By tracking unit movements into the Cairns-Atherton Tablelands area, where non-deployed Australian forces were training, one may determine that a decision to raise the 1st Australian Beach Group was made in late September 1943.[xii] Throughout October, Land Headquarters informed those units that had been identified for inclusion in the beach group.[xiii] With a concentration date set for 17 November 1943, the compressed time frame meant that the majority of units selected were already located nearby in the Atherton Tablelands.[xiv]

The 1st Australian Beach Group coalesced from 15 November 1943, when the various component units concentrated at Deadman’s Gully just north of Cairns.[xv] The group was originally placed under command of the 6th Australian Division (indeed, some early correspondence referred to it as the ‘Beach Group, 6th Australian Division’). Its first training instruction was released the next day, 16 November, by the inaugural chief instructor, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Lionel Rose. Rose had been attached from Headquarters, I Australian Corps to the 6th Division since 6 October, charged with ‘the formation of [the] Beach Group and [its] training … at Cairns’.[xvi] He was a good choice: he had previously been a staff officer at the Directorate of Military Operations and Plans at Land Headquarters, an instructor at the First Australian Army Combined Training School and a liaison officer to the US 2 ESB.[xvii] Rose was also ably assisted by several officers who had been instructors at the recently disestablished Amphibious Training Centre at Toorbul Point in Queensland. In February 1944, these specialists would form the 1st Australian Military Landing Group, the expert body of amphibious staff planners who would augment divisional and brigade headquarters during the planning and execution of amphibious operations.[xviii] Rose would later move back to corps headquarters, assisting in overall amphibious training and doctrine development. In 1945 he would observe the actions of the beach groups during the three Oboe landings and pen the after-action reviews to refine the structures and procedures further.

Australia decided to base the new beach group organisation on the British model—but with certain differences and adaptations.[xix] Indeed, the term ‘beach group’ itself was British in origin. Australia would maintain the Royal Navy/Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Beach Commando organisation that was attached for landings. The RAN Beach Commando marked the landing beach, coordinated the beaching and turnaround of craft with the senior naval officer afloat, and conducted recovery and salvage of damaged landing craft.[xx] During Operation Postern this function was shared between US Navy and 2 ESB personnel.[xxi] Australian planners determined to allocate one beach group per division, not one per brigade as the British had done. Landings in Europe were planned to be multi-divisional in nature, landing on wide open beaches with easy exits. By contrast, in the SWPA, the Australians considered an amphibious landing beyond divisional size unlikely. Accordingly, there was no need for the beach groups to work with each other or come under an umbrella command. Likewise, the terrain of the SWPA was one of small and narrow beaches hemmed in by dense jungle with few, if any, usable tracks for vehicular traffic. This would influence the types of units allocated to the beach group. Differences in beach terrain in the SWPA placed far greater emphasis on engineers with heavy plant to make exits and roads into the jungle and on transport units for negotiating restricted tracks that were likely to be soft surfaces. By contrast to the European theatre, where dump areas were ordinarily located some miles from the beach, under jungle conditions dump areas were often no more than 800 metres inland.

The nature of the SWPA operating environment highlighted the importance of the key plan selecting the best terrain at the beachhead in which to place the various dumps, workshops, vehicle parks and so on. Port operating companies—which were part and parcel of the British model—were deemed unsuitable for the predicted operating environment with few developed ports. They were, however, kept at corps level and could be allocated to the beach group if required. Two other terrain influences in the SWPA modified the Australian model. Many amphibious landings in the SWPA had been ‘wet-shod’—that is, the landing craft had not been able to beach due to shore gradients and other oceanographic features. As a result, many vehicles ‘drowned’ when disembarking. This necessitated the addition of a salvage unit. Likewise, in the SWPA tropical diseases had often taken more of a toll than enemy action, so the Australian model included a malaria control unit capable of spraying large areas with insecticides.[xxii]

It is fascinating to observe the ongoing tension between the British and American models and doctrine within the Australian Army at that time. For example, the amphibious command and staff courses run by I Australian Corps used a combination of US and British texts. Those studied included British combined operations pamphlets such as Beach Organisation and Maintenance and the US FM 31-5 Landing Operations on Hostile Shores and FTP 167 Landing Operations Doctrine, US Navy.[xxiii] One may observe that the conduct of amphibious operations themselves, with the almost complete reliance on US Navy ships and US Army landing craft commanded by the US 7th Amphibious Force (which also assumed carriage of amphibious training), steadily infused the American methods and doctrine into Australian training and operations. However, the British influence (Australia relied almost wholly on British-issued manuals and doctrine until 1941) remained strong.[xxiv] Use of British nomenclature (‘combined operations’) continued and it remained the case that several key staff officers at corps headquarters were British or had been exposed to British amphibious schooling. For example, the general staff officer (GSO) 1 (Combined Operations) at I Australian Corps was Lieutenant Colonel TK Walker, Royal Marines.[xxv] In the structure and doctrine of the beach group, the British model held almost total sway. Indeed, the Australians had specifically rejected the US engineer boat and shore regiments as a basis for a potential beach organisation after Operation Postern. The after-action report noted that the landing beaches in the operational area required an organisation that focused solely on the ‘shore’ aspects of a landing. This included the need for organic signals, supply, transport (with vehicles) and engineers (with plant) that could work independently without calling on divisional resources.[xxvi]

Initially the 1st Australian Beach Group comprised a pioneer battalion, a field engineer company, a heavy equipment platoon, an Army beach signals section, an anti-aircraft battery, a field ambulance, a field workshop, a beach ordnance detachment, a provost section and the RAN Beach Commando. The first 20-day training program was comprehensive. It was immersive and began with classroom theory, progressing to model and ‘dry-shod’ exercises before culminating in the practical—and most challenging—aspects of amphibious operations such as embarkation, landing and setting up a BMA. Although the group initially had access to only a limited number of small landing craft, they were incorporated constantly into all aspects of practical training. This meant there was some commonality—amphibious doctrine and general responsibilities—mixed with role-specific training. The pioneers focused on handling stores and beach defence; the field company (with the heavy equipment section attached) trained for road-making through the jungle with and without mechanical equipment, preparing beach exits, demolishing sandbars and mine clearance and gap marking; the ordnance detachment practised the creation and camouflage of stores dumps; and the field ambulance prepared for setting up a beach dressing station and the evacuation of wounded soldiers seawards.[xxvii] The Cairns surrounds admirably replicated the jungle, swamp and beach terrain that would subsequently be encountered in the SWPA.[xxviii]

On 29 December 1943, the group expanded with the addition of a general transport company, a RAN Beach Signals Section, a supply depot platoon, and malaria control and salvage units.[xxix] At this point its first commanding officer, Colonel Harold Redvers Langford OBE MC, also marched in, marking the point at which the group headquarters became a genuine command element rather than just a training one. This change would be later reflected in I Australian Corps routine orders, which officially designated it ‘Headquarters, 1st Australian Beach Group’.[xxx] From 1 January 1944, the beach group came under command of I Australian Corps, which was a far more fitting command arrangement reflecting the fact that the beach group would be in support of, but not part of, any landed divisional force.

| Unit Type | Role |

|---|---|

| Beach Group Headquarters | Conformation of key plan, BMA reconnaissance, linking up with brigade and divisional HQs, overseeing beach and construction of BMA |

| RAN Beach Commando | Marking of beach, control of inwards and seawards movement of craft to and from the beach |

| Beach Signals Section (RAN) | Communications between naval authorities ashore and those afloat |

| Beach Signal Section (Army) | Internal beach group communications, communications with landed units and headquarters, providing communications between units and headquarters afloat during assault |

| Pioneer Battalion | Assisting Royal Australian Engineers units in engineering tasks, provision of beach companies for stevedoring, close-in defence of BMA, guarding prisoner-of-war cage, building latrines |

| Royal Australian Engineers Beach Group Company (+) | Clearance of obstacles and mines, disposal of unexploded ordnance, marking of gaps, creation of dump areas, creation of lateral and inland roads, laying of mesh on beach for heavy vehicles, creation of beach exits, creation of water supply, construction of beach lighting |

| Supply Depot Platoon | Receiving and accounting for all forces supplies and bulk water coming ashore and within BMA dumps; providing stock states to HQ 9th Division |

| Bulk Issue Petrol Oil Depot (BIPOD) | Establishment of BIPOD as per key plan; handling and issue of all petrol, oil and lubricants; providing stock states to higher command formation |

| General Transport Company | Transporting stores to dumps within the BMA |

| Australian Army Medical Corps Beach Company | Establishment of field ambulance and beach dressing station, beach surgical team and casualty embarkation officer (back-loading of casualties from shore to ship) |

| Malaria Control Unit | Malarial control measures within the BMA |

| Ordnance Beach Detachment | Establishment and management of forward ammunition depot, replenishing units as required, sending ammunition state to higher command formation |

| Electrical and Mechanical Engineer Detachment | Establishment of beach workshop for first-line repairs and vehicle recovery section for ‘drowned’ vehicles |

| Beach Group Provost | Signposting, traffic management within and from the beachhead, straggler control, policing beaches to prevent looting |

| Salvage Unit | Collecting salvaged equipment from beaches and within BMA for either reissue to ordnance or evacuation seaward |

Note: It is notable that by the time the beach groups were employed in 1945, the Allies had complete air superiority and so there was no requirement for an organic anti-aircraft battery to defend the beachhead.

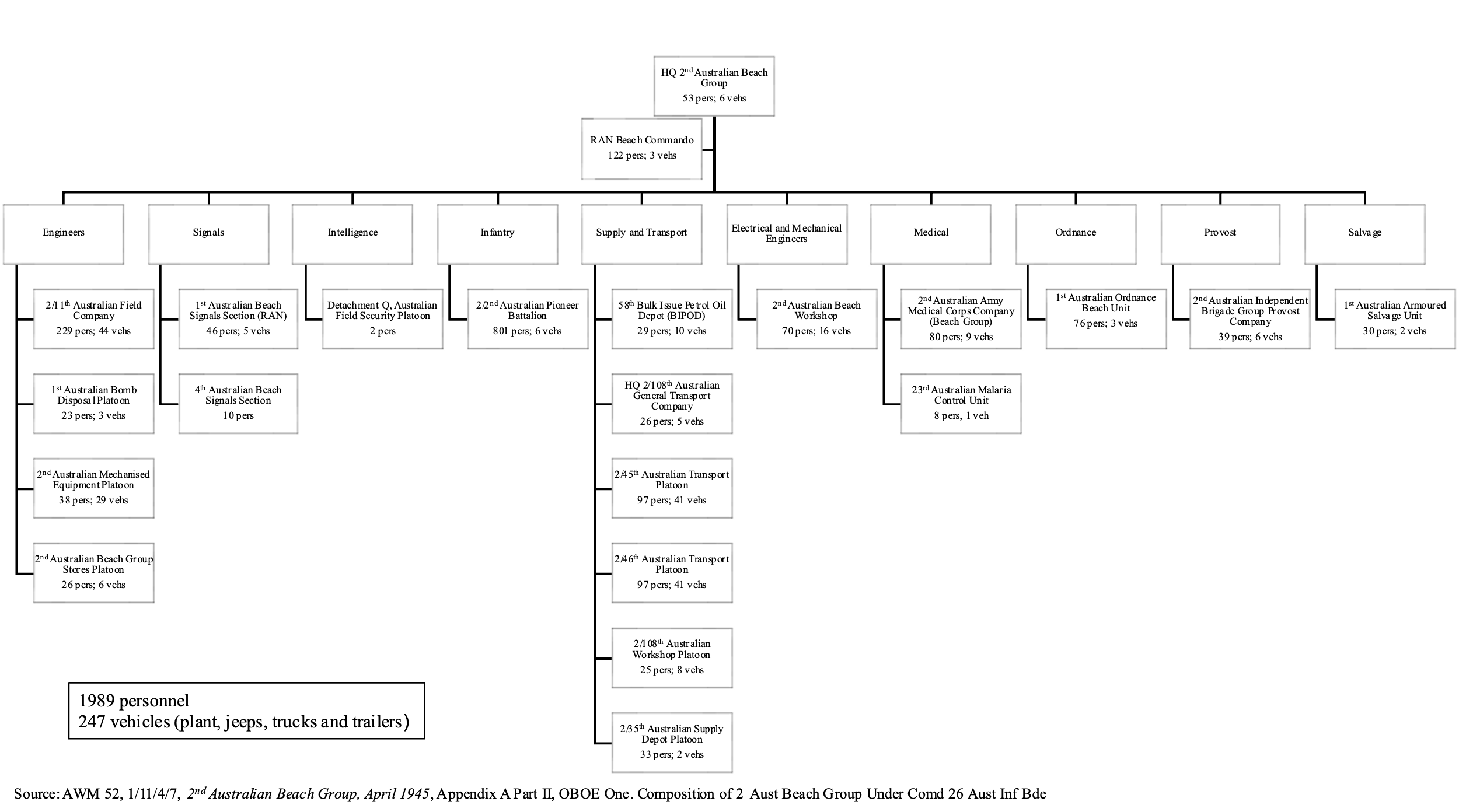

Initially the basic composition of the group headquarters was very lean. Its commanding officer was a colonel; this rank was usually reserved for staff appointments rather than command ones, but such a rank was necessary considering many of the group’s subordinate units were commanded by lieutenant colonels. The other officers comprised a staff captain (responsible for the administrative and logistical functions within the group), a major DAQMG (responsible for amendments to the key plan and oversight of the BMA); a lieutenant intelligence officer (siting of the BMA based on intelligence products); and a lieutenant GSO3 (responsible for the current operations functions). Within the other ranks, the headquarters had one draughtsman, six to seven clerks, one intelligence dutyman, six batmen, two cooks and three general duties staff. Later this headquarters would increase in establishment based on identified gaps in capability. For example, significantly more general duties soldiers were added along with two staff captains, assisted by staff learners, who were appointed to provide a dedicated officer for each of the ‘A’ and ‘Q’ functions.[xxxi] Attached to the group was the RAN Beach Commando of about 18 officers and 113 other ranks, which comprised a principal beachmaster, a deputy principal beachmaster, three beach parties, a boat repair and recovery team, and a naval signals section. In total, when all subordinate units of a beach group came together, including the standing headquarters and the RAN Beach Commando, the basic organisation was just over 1,800 men. This figure waxed and waned depending on unit strengths and ad hoc attachments to the beach group for specific tasks. For example, at the Tarakan landing (Oboe 1), the 2nd Australian Beach Group comprised 1,989 men and 247 vehicles of all types.[xxxii]

Figure 1. Units, with personnel strengths and associated vehicles, for the 2nd Australian Beach Group for Operation Oboe 1, May 1945

There is little evidence that a specific type of officer was selected to be a beach group commanding officer. However, the high quality of command and operational experience among appointees would suggest that the importance of the beach group to an amphibious operation’s success was well understood by the chain of command when selecting candidates. The only commonality was that all had been commanding officers as lieutenant colonels. Two had been wounded in action and three were decorated for performance during this previous command.[xxxiii] Two were older than average for officers at that stage of the war. Indeed, decisions of medical boards caused the 1st Australian Beach Group to cycle through its first two commanding officers (Langford aged 49 and Colonel William John Wain DSO aged 45) within eight months. Colonel Clement James Cummings OBE assumed command on 28 August 1944 and remained in command throughout the rest of the war.[xxxiv] The 2nd Australian Beach Group enjoyed far greater command continuity; its inaugural commanding officer, Colonel Charles Ralph Hodgson, remained with the group throughout, leading it at both Tarakan and Balikpapan. For the latter operation, Hodgson was awarded the DSO for ‘excellence and flexibility of his planning … organisation, leadership and energy’.[xxxv] The other key staff officers on the beach groups’ headquarters, the DAQMGs, had more homogenous backgrounds. Prior to his appointment as the DAQMG in the 1st Australian Beach Group, Major John Ebsworth Gannon, had been a ‘Q’ staff captain on the corps headquarters. Likewise, his equivalent in the 2nd Australian Beach Group, Major Keith Charles Collins, had completed staff courses prior to being posted to Headquarters I Australian Corps as a ‘staff learner’.[xxxvi]

The training program of the beach group expanded with the addition of new subordinate units in late December 1943. In addition to Beach Training Group Instruction No 1 and ‘applicable combined operations pamphlets as they become available’, training was guided by I Australian Corps Training Instruction No 2—Combined Operations, Beach Organisation and Maintenance of December 1943.[xxxvii] Indeed this latter instruction became the foundational document that guided the training, development and deployment of the beach group from that point forward.[xxxviii] Throughout 1944, the 1st Australian Beach Group conducted a series of exercises in support of various formations. This allowed a constant finessing of skills in the development of the key plan and the BMA. It also gradually progressed amphibious knowledge among the 7th and 9th Divisions, which the groups supported. When the Landing Ship Infantry (LSI—a troop carrier) HMAS Kanimbla became available, the group studied ship’s routine, lowering of craft and embarkation of troops.[xxxix] Likewise, when a Landing Ship Tank (LST—the large workhorse of the amphibious fleet, capable of beaching) was allocated for training, the group practised ‘tactical and economical loading … and the method employed and times required in unloading stores and vehicles’.[xl] Reviewing such training, it is apparent that the lessons learned from and before Postern were woven constantly into the group’s training throughout 1944. The training stressed unity of command and clear delineation of responsibility for creation and management of the beach area; inclusion of units of sufficient strength and capability to undertake all the identified functions necessary for a beachhead; deep familiarisation with working with, in and around ships and other craft, and finally constant practice in designing a key plan and then actually creating a beach maintenance area on the tropical north Queensland beaches. The guiding principle that underpinned training and organisation was that the beach group was to establish a BMA:

to receive and handle all stores, vehicles and equipment required by the fighting troops and have them available for issue on demand. The BMA fulfils the functions of an ordinary Base Sub-Area and of re-filling points in the field from the time of an assault landing to the time when the normal system of replenishment in the field is operating through captured ports.[xli]

Throughout 1944, the 1st and 2nd Australian Beach Groups participated in no fewer than five major brigade-level amphibious exercises wherein landing craft were used and full BMAs designed and constructed. In each of these exercises, personnel, stores and vehicles were unloaded so a genuine understanding of work rates and troops to task could be gained and improved upon. Such exercises also finessed the beach groups’ understanding of the priority of landing. A comparison of the landing tables of these exercises with those of the three Oboe landings is illuminating, showing that training informed operational practice. The first elements to land—either in the initial wave or not long after—were the RAN Beach Commandos and the beach control companies. Next were elements of the RAN and Army beach signals section. With these elements landed and operational, a command-and-control structure was present on the beach to coordinate landings. Within 10 to 20 minutes, elements of the medical section landed to establish a dressing station, while parties of engineers with dozers and mesh sleds began preparing the beach for the arrival and passage of heavy vehicles. At this time the reconnaissance party from the beach group headquarters landed. Its role was to determine the suitability of the first key plan and whether any modifications needed to be made once the true state of the terrain was understood. From that point forward, the beach group would build up, with the pioneers landing in time to unload the stores that came in the later post-assault waves.

Comprehensive training supported the overall infusion of amphibious competency in I Australian Corps generally. Staff from the 1st Australian Beach Group, with key amphibious experts at corps headquarters, assisted in the creation of the 2nd Australian Beach Group, which was raised in March 1944. In supporting a 10-day command and staff course, 1st Australian Beach Group established a full beach maintenance area so that students, equipped with the key plan, could understand the importance of selecting firm ground, the space required for a BMA to support a division, and what a BMA looked like up to H + eight hours after a landing. The group also instructed the students on the mechanics of landing, including the method of control by beach group headquarters, the method of RAN and Army control of the beaches, the system of traffic control, the movement of stores from craft to dumps, and the types and capabilities of mechanical equipment needed to create a BMA on narrow beaches surrounded by dense jungle.[xlii]

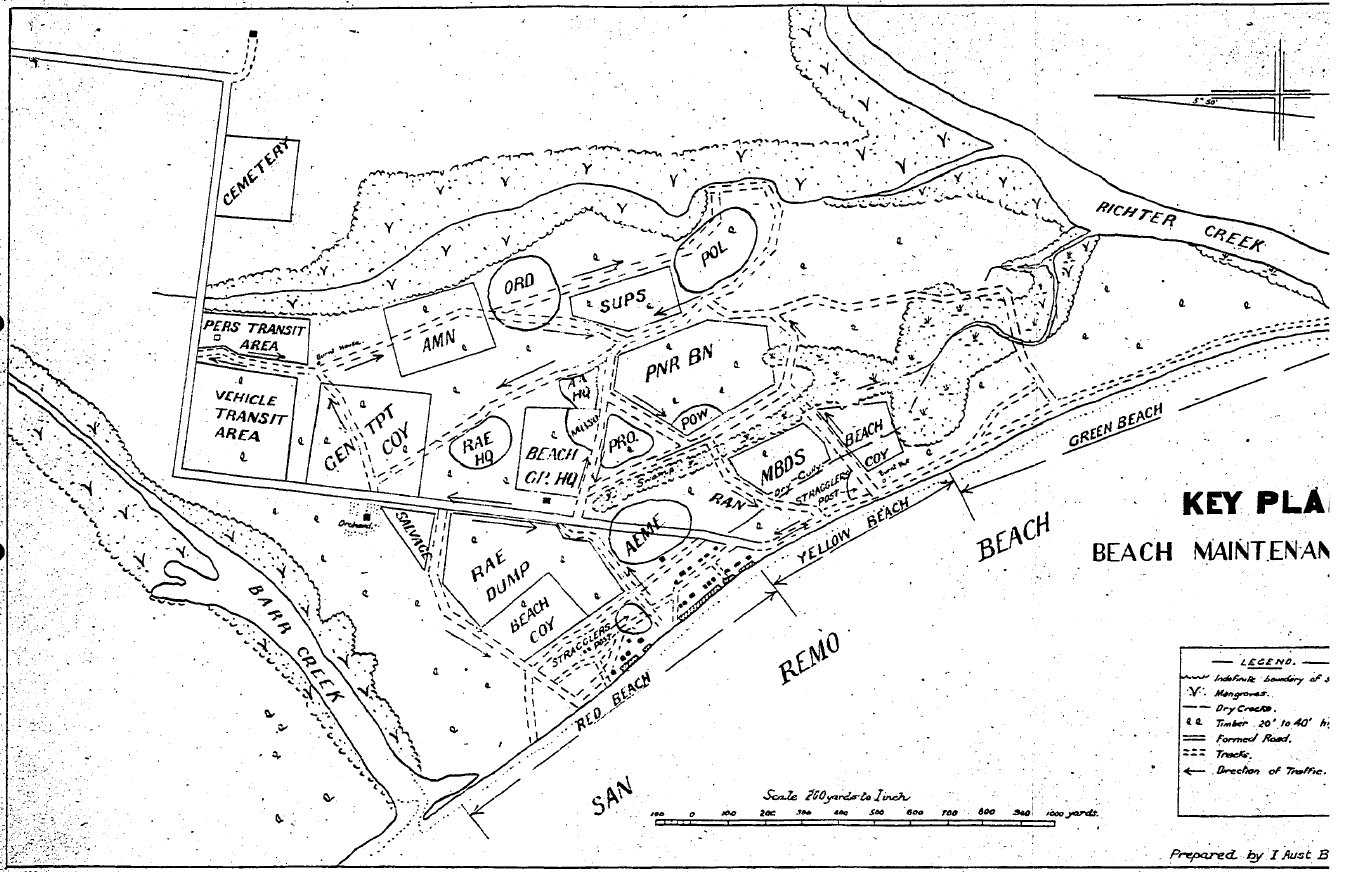

Figure 2. Key plan in support of the command and staff course An initial key plan set out the proposed layout of a BMA. A second key plan was released after landing and included changes resulting from on-the-ground reconnaissance that confirmed the suitability or otherwise of terrain. (Source: AWM 52, 1/11/2/2, 1st Combined Operations Section, July 1944, Amphibious Training)

Operation Oboe—the Organisation is Proven

It is not the intention of this article to detail the rationale or overall operational specifics of the three Oboe landings conducted by the 7th and 9th Divisions of I Australian Corps during May to July 1945. These matters have been debated before and have been covered elsewhere.[xliii] For the purposes here, a brief outline is sufficient. The landings took place at three locations on the island of Borneo. Each assault staged from Morotai and was heavily supported by US Navy ships and US Army landing craft. The Allies had air superiority and the Japanese defenders were fixed on the island—noting that MacArthur had already captured the Philippines, dislocating Borneo from the Japanese home islands.

Oboe 1 was the landing on Tarakan, a small island off the north-east coast of Borneo, by the oversized 26th Australian Infantry Brigade Group (a formation of the 9th Division) on 1 May 1945. The 2nd Australian Beach Group was allocated to this landing; since this was essentially a divisional (−) landing, it was appropriate and consistent with doctrine for the entire beach group to be used. For the duration of the operation, the beach group was placed under command of the brigade. The salient feature of this landing was that the objective beach was small, narrow and muddy, with a high tide to low tide differential of 250 metres and a tidal range of 3 metres depth. At low tide, this created a long and soft mud flat, whereas at high tide there was effectively no beach, other than a strip of black mud upon which to establish a beachhead. For the purposes of the assault landing, this area was divided into ‘Red’, ‘Yellow’ and ‘Green’ beaches. On ‘P’ Day, ‘H’ Hour was set at 0815. The lead battalions landed at 0816. Elements of the RAN Beach Commando were with the initial assault conducting wave control from a boat on the flanks.[xliv] Three beach control parties (one for each beach) comprising a beach company commander, a RAN beachmaster, two beach control officers and two RAN assistant beachmasters (with a signals section) landed with the first waves of infantry to control landings from the shore.[xlv] These elements were ashore by 0820.[xlvi] The advance headquarters of the 2nd Australian Beach Group was ashore at 0920. One may discern the importance and the role of this advance party by its composition: the DAQMG, the intelligence officer and the ‘Q’ staff captain. This group immediately checked to see whether the reality of the ground would be suitable for the first key plan, which had been designed previously based on intelligence products alone. Once on the ground, this group would have to make major adjustments to the first key plan because of the extremely limited amount of usable ground that was available until the Japanese were pushed further inland.[xlvii] The commanding officer of the group landed at 0930 and the main headquarters was established by 1100. By 1700, most of the group was ashore and discharging its duties.[xlviii]

The group’s activities were complicated by the narrow, muddy shore, the inability to move heavy vehicles off the beach, and the falling tide that beached the heavier vessels just offshore. Several of these vessels remained stranded until the spring tide came in 12 days later. Nonetheless the group unloaded 1,500 tonnes of stores on P-Day and a further 1,200 tonnes on P+1. Lieutenant Colonel Rose, previously the first chief instructor of the 1st Australian Beach Group, was attached to the landing party as an observer on behalf of the 1st Australian Combined Operations Section within I Australian Corps. He later reported that ‘as this is the first operation in which an Australian Beach Group was committed, its activities have been watched with interest’.[xlix] A no-nonsense man who seldom minced words, Rose dryly recorded that the beach parties ‘did excellent work’ and their ‘early beach (mud) reconnaissance, beach marking (day and night) was also well done’. He observed that the pioneers ‘worked like Trojans’ and ‘all dump stocks [were] carefully sorted and stacked. Ammunition, rations, water, petrol, oil, and lubricants [were issued] on P Day’. Rose recommended that the provost element be increased by two sections as they were ‘overworked and totally inadequate in strength’. Overall, he assessed:

Serious congestion has been avoided so far by good organisation. BMA cramped by tactical situation and will not be easy till a traffic circuit is obtained through Tarakan … the doctrine is sound and faithfully carried out. In the worst conditions probably of any theatre, no other system could have achieved the result obtained.[l]

Worthy of note also was that the group’s organic pioneer battalion was required to act in the close defence role on the night of 1–2 May clearing Japanese remnants within 1 kilometre of the beach.

Figure 3. Troops landing at Tarakan after the initial assault waves. The image shows the LST berthed alongside pontoon bridges. In the foreground the narrow, muddy shoreline is covered in debris caused by the pre-landing bombardment. The RAN assistant beachmaster (white cap and beard) directs troops across the beachhead. (Source: AWM 090882)

The two subsequent landings, Oboe 6 in Brunei in June and Oboe 2 at Balikpapan in July, were successful. In Oboe 6, the 1st Australian Beach Group, supporting the 9th Australian Division (−), landed in good order, on time, and began operations according to the schedule and doctrine. The first key plan needed little adjustment and a BMA was constructed quickly, accompanied by the efficient unloading of stores.[li] The engineers’ heavy plant (graders and mobile cranes in particular) proved their worth. The commanding officer, Colonel CJ Cummings, later wrote that the group’s plan for, and action during, the landing:

was based wholly on the training the Group had received and was in accordance with the principle set out in I Australian Corps pamphlet Beach Organisation and Maintenance. It is considered … those principles … to be correct.[lii]

Cummings was also sure that his soldiers knew they had done well. In an order of the day, he passed on that the operation’s naval commander, Rear Admiral Royal, US Navy, had visited the beach area and ‘stated that it was the neatest job he had ever seen as far as control and clearance of the beaches and stacking at dumps was concerned’.[liii]

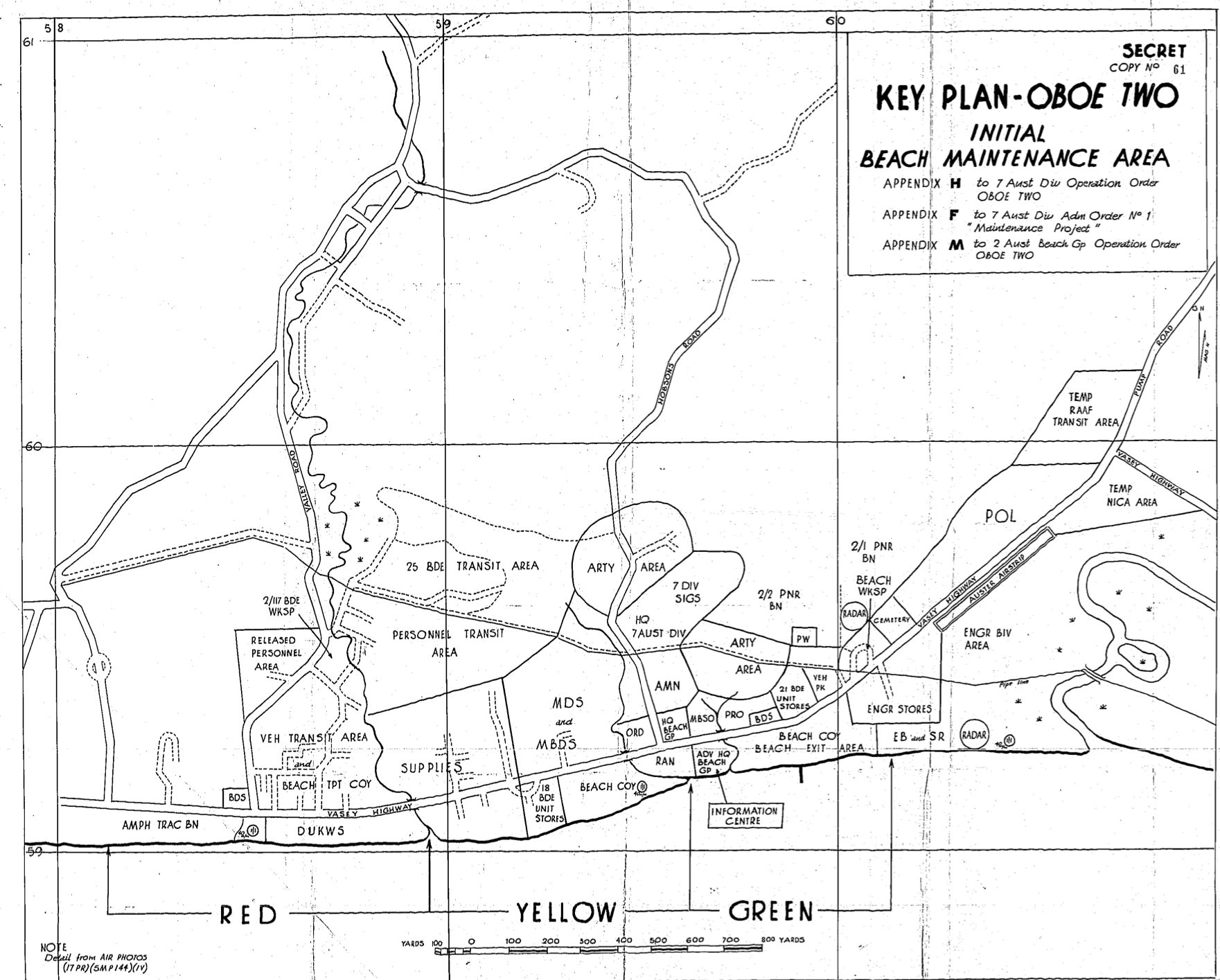

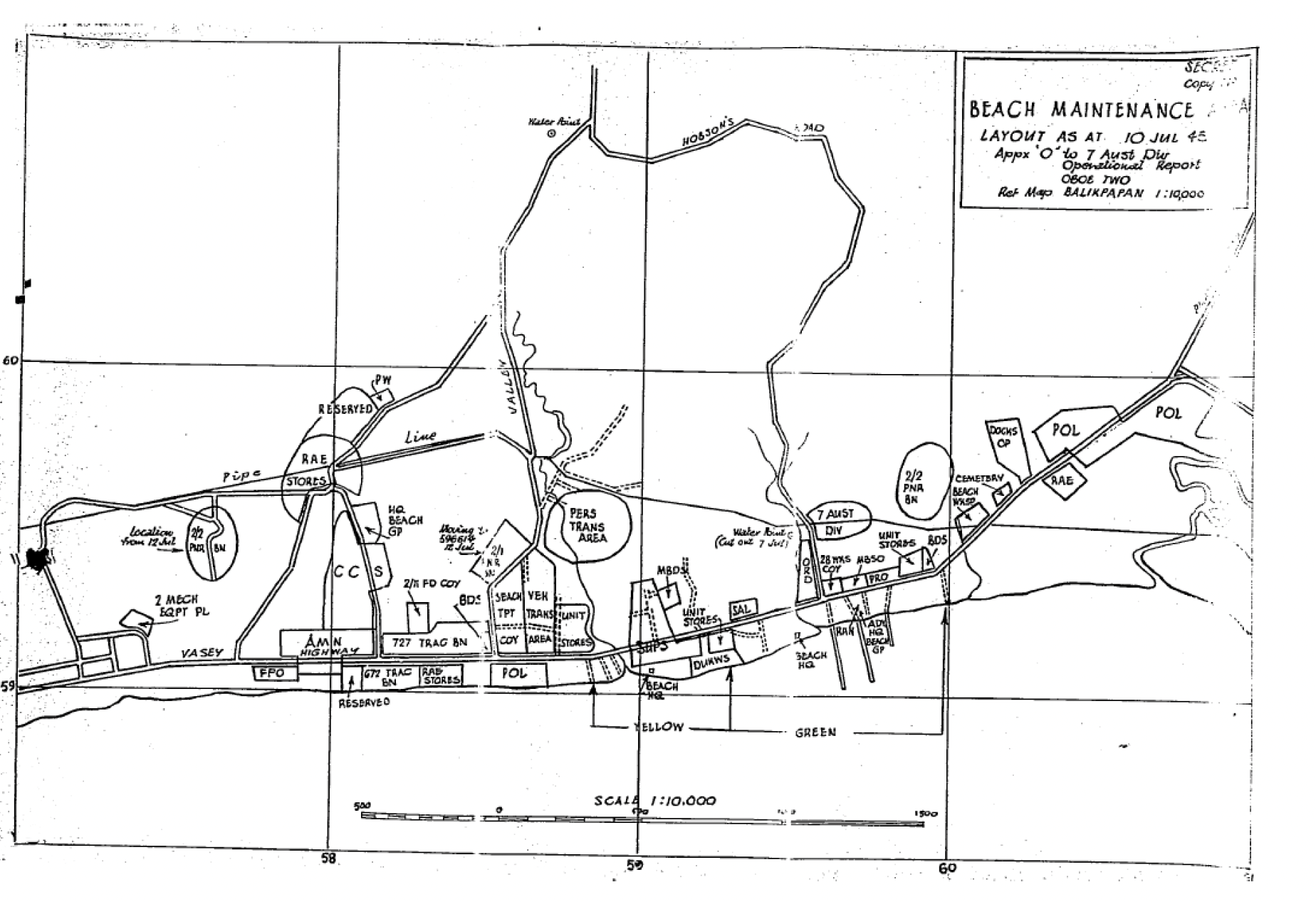

The landing at Balikpapan—Oboe 2—was conducted by the 7th Australian Division and supported by the 2nd Australian Beach Group, which had withdrawn from Tarakan in late May. This would be the first and last time an Australian beach group worked in concert with a full divisional landing. Again, the landing area was divided into three beaches—‘Red’, ‘Yellow’ and ‘Green’. F-Day was set for 1 July 1945; H-Hour was 0900. As per doctrine, beach control teams went in with the first waves. The next elements of the 2nd Australian Beach Group, including its commander, Colonel Hodgson, and the RAN beachmaster, Lieutenant Commander Morris, had landed in the fifth wave, setting up advanced headquarters on ‘Green’ Beach at 0935 and ‘Yellow’ Beach at 0945.[liv] The beach group’s medical company set up soon thereafter and treated its first casualty at 1005.[lv] The beach itself was superior to the mangroves and mud that Hodgson and Morris had experienced at Tarakan. The firm beach and lack of dense mangroves meant that vehicles were not bogged and could exit efficiently off the sand. The BMA was reconnoitred and signposted within two hours of the landing depots. Unit areas were established in accordance with the first key plan and were receiving stores by the evening of 2 July. In the initial stages, the small amphibious trucks known as DUKWs brought 3-inch and 4.2-inch mortar and 25-pounder ammunition directly from the ships to the weapons, while other ammunition was shipped to beach dumps operated by the 2/1st Ordnance Beach Detachment. These dumps remained in use longer than anticipated because the dump area allocated on the first key plan was found to be boggy and thus unsuitable.

Figure 4. The first key plan for Oboe 2, created before the landing (Source: AWM 52, 1/5/14/74, 7th Australian Division General Staff Branch, June 1945 Operations Orders, Oboe Two, ‘Appendix H to 7th Australian Division Operations Order for Oboe Two’)

The versatility and utility of the beach group was demonstrated in other ways. Elements of the 23rd Australian Malaria Control Unit landed on ‘F’ Day and began work almost immediately spraying the entire BMA with pyrethrum. Later this effort was augmented by DDT spraying to the point at which the unit was able to record a steady decline in both the adult and larval mosquito populations.[lvi] The beachmaster, Morris, ordered construction of two pontoon jetties on ‘Green’ Beach, using sections of pontoons that had been towed ashore by landing craft. This would create a U’ shaped jetty facility intended to handle four LST simultaneously. On ‘F’ Day he also ordered construction of a smaller pontoon causeway on ‘Green’ Beach. This allowed the first Landing Craft Mechanised (LCM) to land and unload at 1510. The larger project would take two days to complete, assisted by the famous ‘Seabees’ of the US 111th Naval Construction Battalion. When the U-shaped facility was operational on 3 July, it could only handle two rather than the planned four LSTs at a time, and it required LCMs to buttress the pontoons to stop them moving unduly in the swell. Nevertheless, it greatly sped up unloading of LSTs, for which the average unloading time was about seven hours. Despite this temporal success, the jetty could only be considered a stopgap measure; one report noted that it had been planned that 10,000 tons of supplies and all the vehicles would be unloaded in the first 48 hours. Instead, only 2,000 tons and half the vehicles had been unloaded in this time.[lvii] Due to the rapid collapse of the Japanese defences, this deficiency did not cause undue concern. Nevertheless, the beach group understood that an alternative beaching/docking arrangement was required and began scouting for alternative areas around Balikpapan. The group found a suitable location further into Balikpapan harbour and helped construct the landing area for the LSTs.[lviii] This allowed for a greatly expanded BMA that was also able to utilise port facilities. The 2/3rd Australian Docks Operating Company, who were corps troops, were attached to the 2nd Australian Beach Group for this phase of the operation.[lix]

Figure 5. The key plan of the BMA as of 10 July 1945 showing similarities and differences to the first key plan. Part of the beachhead proved unsuitable for certain functions once on-the-ground reconnaissance was conducted. (Source: AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945)

It is salient to note that after the conduct of all three Oboe landings, with beach groups involved in each, a conference was convened on 29 July 1945 to examine any proposed improvements to the beach group’s organisation or employment. No change in the method of the beach group’s employment was contemplated. The conference therefore reiterated that a beach group should be organised so that it could:

- develop a BMA for a division

- handle 900 tons of deadweight stores during the first 24 hours of an operation and an average of 1,500 tons per day thereafter

- hand over all responsibility to a base sub area from two to four weeks after the initial landing.

With the exception of adding some extra staff to the group headquarters, increasing the size of the provost detachment (as noted previously by Rose) and ensuring certain divisional attachments were assigned to the beach group for the conduct of the landing, no major organisational changes were recommended.[lx] It was observed that an entity akin to the US Navy construction battalions would be useful but unlikely to be raised by Australia; therefore the US unit should be attached to the beach group for any subsequent operation. Ultimately these deliberations were moot. There would be no further amphibious operations in the war and thus no further need for the beach groups. On 21 October, the headquarters of 2nd Australian Beach Group was ordered to disband immediately, and its remaining subordinate units were placed under command of the 7th Division.[lxi] The 1st Australian Beach Group, still in Brunei Bay, received its orders on 21 November and was disbanded on 25 November 1945.[lxii] The short-lived but immensely successful Australian beach groups were no more.

Conclusion—‘To Cope with Any Given Task’

The beach groups were an excellent example of adaptation in war, identifying a deficiency and a resulting need, then crafting a solution in turn. The hard work of adaptation was mainly done by the British. Despite being under US command and beholden to the US for ships and craft, the Australians were nevertheless able to leverage their deep interconnectedness with the British. Australia took the beach group model, finessed it for tropical service and then used it to great effect. It was a fit-for-purpose and a fit-for-environment organisation that enabled division-sized amphibious operations to be conducted within jungle-hemmed shorelines. It acted as the interface between the sea and the land, facilitating the transfer of the landed force and its sustainment from its transport and support afloat through the beachhead into the objective area. In modern parlance, the beach group linked the land and maritime domains, enabling cross-domain mobility.It was an organisation that could communicate with US forces but also incorporate British best practice, highlighting interoperability. By integrating RAN commandos, and coordinating ship-to-shore and shore-to-ship movement to support operations and sustainment, the beach groups were enabling cross-domain effects.[lxiii] Importantly—and in stark contrast to Operation Postern—there were clear lines of responsibility within a unified command and control structure, which itself is a prerequisite for successful amphibious operations.

As the Australian Army reconfigures as a littoral manoeuvre force, is there an enduring need for some organisation akin to the beach groups? The problem of sustainment in amphibious and deployed operations is well known. But the proliferation of long-range precision munitions, enabled by ubiquitous multi-domain surveillance and reconnaissance, would suggest that large beachheads with contiguous dumps are now a critical vulnerability. In response, dispersed operations and dispersed logistics have been put forward as a possible solution. While this briefs well, such a concept largely makes the sustainment afloat (i.e. ships conducting sea-basing) the new target instead of the beachhead. Other than caching, there remains a requirement to supply troops ashore and to evacuate them rearwards when needed. Certainly there is—presently anyway—no thought of conducting divisional landings à la 1945. Even if a battlegroup-sized unit is the largest organisation to be deployed and sustained, and a large beachhead and maintenance area is not required, a logistics challenge remains. Innovative use of technology may assist in some way, but it will not entirely remove the sustainment problem inherent in this type of operation. One thing is for certain: by determining that its raison d’être is littoral manoeuvre, the Australian Army must pay greater attention to deployed logistics and rebalance itself accordingly.[lxiv]

Ultimately ‘littoral’ means more than just ‘amphibious’. Nevertheless, given that the ADF’s nascent littoral manoeuvre concept is underpinned by the acquisition of Land 8710 landing craft and interoperability with the Australian Amphibious Force, sea–land domain interaction would seem to remain the primary one to develop. Within the primary area of military interest, there are far fewer virgin beaches and thick jungle shorelines than in 1945. Instead there will be urban-littoral areas of varying size and composition. This terrain change would certainly affect any manoeuvre and support plans and force compositions as a result. Seizing or securing an operational port may be easier than establishing a forward logistics node requiring over-the-beach sustainment. If so, the modern equivalent of the port operating companies may have some utility. The air domain will play a part in both manoeuvre and sustainment. Indeed, it is not beyond the realms of possibility to have air liaison officers, landing zone markers and controllers and other specific air-centric (rotary or fixed wing) enablers within a ‘littoral support group’. It remains to be seen whether the integration of space and cyber capabilities would be necessary (or possible) in such a group.

Whatever its makeup and the nomenclature chosen, and despite the very different operating environment to that of 1945, there would seem to be an enduring need for an organisation that can enable a combat force to move between domains and can then sustain it in the future operating environment. Perhaps as the Australian Army grapples with the definition, requirements and realities of littoral manoeuvre in a contested environment, it may be instructive to look back on the guiding principles behind the Australian beach groups 80 years ago. ‘The Australian Beach Group’, said one precis, ‘must be regarded as a trained and organised nucleus which is well able to absorb and employ increments which may be considered necessary to cope with any given task’.[lxv] The challenge now is to define the task so this nucleus can be ‘trained and organised’.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Dayton McCarthy is currently the Staff Officer Grade 1 Special Projects in the G5 Cell, Headquarters 2nd (Australian) Division. He served in the Australian Regular Army from 2005 to 2013 in a number of regimental, training and staff appointments. Transferring to the Army Reserves in 2014, he was the Commanding Officer of the 9th Battalion, Royal Queensland Regiment from 2021 to 2022. A defence analyst in his civilian career, LTCOL McCarthy is the author of several books and numerous conference papers, articles and book reviews. He has a Doctor of Philosophy and a Graduate Diploma in Science (Operations Research and Systems) from the University of New South Wales.

Endnotes

[i] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance, Chapter One’ dated 12 December 1943.

[ii] Within 2 ESB were several engineer boat and shore regiments. These comprised a boat battalion (small craft) and a shore battalion (beach management and stevedoring).

[iii] David Dexter, Volume VI—The New Guinea Offensives, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series One—Army (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1961), pp. 281, 332–335.

[iv] Rhys Crawley and Peter Dean, ‘Amphibious Warfare: Training and Logistics, 1942–45’ in Peter J Dean (ed), Australia 1944–45. Victory in the Pacific (Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2016), pp. 262–225; Rhys Crawley ‘Supplies over the Shore: Logistics and Australian Littoral Operations’, Australian Army Journal XIX, No. 2, pp. 73–76.

[v] AWM 52, 1/5/20/36, 9th Australian Division General Staff Branch, August 1943, ‘Notes on Conference held at Joint Planning HQ 14 Aug 43’ dated 14 August 1943.

[vi] AWM 52, 1/1/1, Land Headquarters, Directorate of Staff Duties, December 1943, Part 1, ‘Seventh Amphibious Force, Report on Operation POSTERN’ dated 30 September 1943.

[vii] AWM 52, 1/5/12, 6th Australian Division General Staff Branch, September 1943, ‘Notes on 6 Aust Div Amphibious Training, Period 16 to 28 Aug 43’ dated 2 September 1943.

[viii] AWM 52, 1/5/20/36, 9th Australian Division General Staff Branch, August 1943, ‘Reasons for ESB Participating in Training’ dated 2 August 1943.

[ix] AWM 52, 1/5/20/44, 9th Australian Division General Staff Branch, 1943–1944 Operations, ‘9 Aust Div Report on Operations, 2 Oct–15 Jan 44’, ‘Section II—Lessons General’ no date.

[x] AWM 52, 1/11/2/2, 1 Australian Combined Operations Section, July 1944, Amphibious Training, ‘Amphibious Training I Aust Corps, Command and Staff Course: 20 Jul–30 Jul 44. Precis No 7—Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ no date.

[xi] For more information on the three amphibious landings conducted by I Australian Corps (Oboe 1 at Tarakan, Oboe 6 at Brunei Bay and Oboe 2 at Balikpapan) see Dayton McCarthy, The OBOE Landings, 1945, Australian Army Campaign Series 32 (Newport: Big Sky Publishing, 2022).

[xii] AWM 52, 1/1/1/27, Land Headquarters, Directorate of Staff Duties, October 1943, ‘Location Statement—LHQ Units as at 30 Sep 43’ dated 6 October 1943. Unit serial number 45278 referred to the 2nd Australian Beach Signals Section.

[xiii] For example, see AWM 52, 1/2/1/15, Advanced Headquarters, Australian Military Forces General Staff Branch, October 1943, ‘Message Landops to Landforces SD1389 and SD 1390’ dated 27 October 1943.

[xiv] AWM 52, 1/5/12, 6th Australian Division General Staff Branch, October 1943, War Diary entry for 18 October 1943. Notable exceptions were 228th LAA Battery, which travelled from Western Australia, and 2/12th Field Ambulance, which was moved from New South Wales.

[xv] AWM 52, 1/11/3/1, 1st Australian Beach Group, October–December 1943, War Diary entry for 16 November 1942 and ‘6th Australian Division Training Instruction Number 21’ dated 16 November 1943.

[xvi] AWM 52, 1/5/12, 6th Australian Division General Staff Branch, October 1943, War Diary entry for 6 October 1943 and ‘Amphibious Training 6 Aust Div’ dated 3 October 1943.

[xvii] Australian Archives B883, NX34700, Service Record of Alfred Lionel Rose.

[xviii] AWM 52, 1/11/5/1, 1st Australian Military Landing Group, November 1943–August 1944, War Diary entries for 1 November 1943 and 1 February 1944,

[xix] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ dated 12 December 1943. This document notes that the ‘staff organisation, the beach group organisation and the methods to be used are based on those now in force in the Middle East’.

[xx] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ dated 12 December 1943.

[xxi] AWM 52, 1/5/20/36, 9th Australian Division General Staff Branch, August 1943, ‘Notes on Conference Held at Joint Planning HQ, 14 August 1945’.

[xxii] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ dated 12 December 1943.

[xxiii] AWM 52, 1/11/2/2, 1 Australian Combined Operations Section, July 1944, Amphibious Training, ‘Amphibious Training—I Aust Corps, Command and Staff Courses: 20 Jul–30 Jul 44. Inspection of a Prepared Beach Maintenance Area and Beach Group Equipment’ no date.

[xxiv] Adrian Threlfall, The Development of Australian Army Jungle Warfare Doctrine and Training, 1941–1945, PhD thesis (Victoria University, 2008), p. 29.

[xxv] AWM 52, 1/4/1, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, November 1943, War Diary entry for 2 November 1943.

[xxvi] AWM 52, 1/5/20/44, 9th Australian Division General Staff Branch, 1943–1944 Operations, ‘9 Aust Div Report on Operations, 2 Oct–15 Jan 44’, ‘Section II—Lessons General’ no date.

[xxvii] AWM 52, 1/11/3/1, 1st Australian Beach Group, October–December 1943, ‘Beach Group Training Instruction No 1—Outline Training Programme of Sub-units—19 Nov–10 Dec’ dated 16 November 1943.

[xxviii] AWM 52, 5/21/15, 2/3rd Australian Railway Construction Company, May–December 1943, War Diary entry for 31 December 1943.

[xxix] AWM 52, 1/11/3/1, 1st Australian Beach Group, October–December 1943, ‘I Australian Corps Training Instruction No 5’ dated 29 December 1943.

[xxx] AWM 52, 1/11/3/2, 1st Australian Beach Group, January 1944, ‘Routine Orders, No 1–3’ dated 18 January 1944.

[xxxi] See AWM 52, 1/11/3/2, 1st Australian Beach Group, January 1944, ‘Field Return of Other Ranks’ dated 1 January 1944 and ‘Field Return of Officers’ dated 1 January 1944; AWM 52, 1/11/3/16, 1st Australian Beach Group, June 1945, ‘Field Return of Officers’ dated 16 June 1945.

[xxxii] See AWM 52, 8/2/26/42, 26th Australian Infantry Brigade—April 1945, Planning Reports, Part 2 of 2, ‘Summary of Forces and Stores to be Loaded—OBOE One’, 14 April 1945.

[xxxiii] Australian Archives B883, QX53209, Service Record of Harold Redvers Langford; WX1576, Service Record of William John Wain; QX6011, Service Record of Clement James Cummings; NX70837, Service Record of Charles Ralph Hodgson.

[xxxiv] AWM 52, 1/11/3/9, 1st Australian Beach Group August–September 1944, War Diary entry for 28 August 1944.

[xxxv] Australian Archives B883, NX70837, Service Record of Charles Ralph Hodgson.

[xxxvi] Australian Archives B883. VX69275, Service Record of Keith Charles Collins; NX 3101, Service Record of John Ebsworth Gannon.

[xxxvii] AWM 52, 1/11/3/1, 1st Australian Beach Group, October–December 1943, ‘I Australian Corps Training Instruction No 5’ dated 29 December 1943.

[xxxviii] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ dated 12 December 1943.

[xxxix] AWM 52, 1/11/3/3, 1st Australian Beach Group, February 1944, Part 1, ‘1 Aust Beach Gp Trg Instruction No 11’ dated 18 February 1944.

[xl] AWM 52, 1/11/3/3, 1st Australian Beach Group, February 1944, Part 1, ‘1 Aust Beach Gp Trg Instruction No 12’ dated 25 February 1944.

[xli] AWM 52, 1/4/1/43, I Australian Corps General Staff Branch, December 1943, ‘I Aust Corps Training Instruction No 2. Combined Operations. Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ dated 12 December 1943.

[xlii] AWM 52, 1/11/2/2, 1 Australian Combined Operations Section, July 1944, Amphibious Training, ‘Amphibious Training—I Aust Corps, Command and Staff Courses: 20 Jul–30 Jul 44. Inspection of a Prepared Beach Maintenance Area and Beach Group Equipment’ no date.

[xliii] See McCarthy, The OBOE Landings; Peter Stanley, Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1997); several chapters in Dean (ed), Australia 1944–45. Victory in the Pacific.

[xliv] AWM 52, 1/11/4/8, 2nd Australian Beach Group, May 1945, War Diary entry for 1 May 1945.

[xlv] AWM 52, 1/11/4/7, 2nd Australian Beach Group, April 1945, ‘Appendix H to 2 Aust Beach Gp OO 1 of 19 Apr 45—2 Aust Beach Gp Landing Tables—OBOE 1’.

[xlvi] AWM 52, 1/11/2/5 1st Australian Combined Operations Section, June–September 1945, ‘Report on Beach Organisation in Operation Oboe One (Tarakan)’ dated 23 June 1945.

[xlvii] AWM 52, 1/11/2/5, 1st Australian Combined Operations Section, June–September 1945, ‘Operations OBOE 1, 2 and 6. Summarised Report on Beach Organisation’ dated 6 August 1945.

[xlviii] AWM 52, 1/11/4/8, 2nd Australian Beach Group, May 1945, War Diary entry for 1 May 1945.

[xlix] AWM 52, 1/11/2/5 1st Australian Combined Operations Section, June–September 1945, ‘Report on Beach Organisation in Operation Oboe One (Tarakan)’ dated 23 June 1945.

[l] AWM 52, 1/11/2/4, 1st Australian Combined Operations Section, September 1944–May 1945, ‘Operation Oboe One. Observer’s Interim Notes to 1400 P Plus 3 by LTCOL A.L Rose (GSO 1, 1st Australian Combined Operations Section)’ dated 5 May 1945.

[li] AWM 52, 1/11/3/16, 1st Australian Beach Group, June 1945, War Diary entry for 10 June 1945.

[lii] AWM 52, 1/11/3/16, 1st Australian Beach Group, June 1945, ‘Report on Beach Organisation Labuan Island Operation OBOE 6 by Colonel C.J Cummings DSO OBE Commanding 1st Australian Beach Group’ no date.

[liii] AWM 52, 1/11/3/16, 1st Australian Beach Group, June 1945, ‘To all Officers, ORs and Ratings 1 Aust Beach Group by Colonel CJ Cummings’ dated 14 June 1945.

[liv] AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945, War Diary entry for 1 July 1945.

[lv] AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945, ‘Medical Report—Operation OBOE Two’ dated 25 July 1945.

[lvi] AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945, ‘Appendix E to Medical Report—Operation OBOE Two’ dated 25 July 1945.

[lvii] AWM 52, 1/5/14/84 7th Australian Division General Staff Branch, September 1945, Report on Operations, OBOE Two, ‘Appendix P to 7 Aust Div Operational Report OBOE Two’ dated 28 September 1945.

[lviii] Ross A Mallett, Australian Army Logistics, 1943–1945, PhD thesis (University of New South Wales (ADFA), 2007), pp. 365–366.

[lix] AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945.

[lx] AWM 52, 1/11/2/5, 1st Australian Combined Operations Section, June–September 1945, ‘Beach Organisation and Maintenance. Review of Existing Australian Organisation’ dated 29 July 1945. It did, however, recommend that the RAN commando be reduced in size, after observations collated from the three Oboe landings indicated that it was in fact over strength.

[lxi] AWM 52, 1/11/4/11, 2nd Australian Beach Group, July–October 1945, War Diary entry for 21 October 1945.

[lxii] AWM 52, 1/11/3/19, 1st Australian Beach Group, September–November 1945, War Diary entry for 21 and 25 November 1945.

[lxiii] For expansion on these concepts—described as ‘tenets’—see Matthew Scott, ‘Tenets for Littoral Operations’, Australian Army Journal XIX, No. 2, pp. 33–38.

[lxiv] Crawley, ‘Supplies over the Shore’, p. 81.

[lxv] AWM 52, 1/11/2/2, 1 Australian Combined Operations Section, July 1944, Amphibious Training, ‘Amphibious Training I Aust Corps, Command and Staff Course: 20 Jul–30 Jul 44. Precis No 7—Beach Organisation and Maintenance’ no date.