Embracing Complexity: An Adaptive Effects Approach to the Conflict in Iraq

Abstract

This article examines the complexity of the conflict in Iraq as the backdrop for a practical approach to effects-based operations. The author proposes an adaptive approach embracing complexity, the goal being to develop a philosophy for the Australian Army that maintains the edge in complex warfighting.

Introduction

The conflict in Iraq demonstrates the complexity of the modern battlespace. This article examines the complexity of that conflict as the backdrop for a practical approach to effects-based operations (EBO) for the Australian Army. A close study of this conflict enables exploration of the human dimension of the operational environment facing the Australian Army. A methodical calculation of all possible scenarios resulting from military action in Iraq as a means to execute EBO underestimates the chaos of human interaction. As the adversary in Iraq is an adaptive human system, success in this battlespace requires an adaptive approach. The intent of this paper is not to dissect EBO or the conflict in Iraq, but rather to examine the points of convergence with the concept of ‘adaptive campaigning’.

The Conflict in Iraq

It is too simplistic to label the conflict in Iraq as an ‘insurgency’. Describing it as such can lead to misconceptions about the variety of armed groups and their motives and the nature of violence existing in that country. There is little doubt that dismantling Saddam Hussein’s regime dissolved the glue that held the fractious nation together. In addition, the removal of both the Ba’athist bureaucracy and the armed forces engendered a survival instinct within Iraqi society. Tribal and sectarian structures have always been important in Iraq, however this framework became the primary social constant in a country suffering significant upheaval. To complicate matters, the loss of border control and the existence of malleable neighbours enabled the jihadist network to establish an effective base in the country. Yet the jihadis represent only some of the armed groups that are active in Iraq.

Estimates vary regarding the number of groups and their shifting alliances, but 70 groups of varying size and capability is a reasonable assessment. Despite their diversity—in ethnicity, religion, goals or targets—one commonality between them has been the struggle for power in Iraq following Saddam Hussein’s downfall. Sunni extremists linked to the global jihad (such as al-Qaeda in Iraq and Ansar al-Sunnah) are focused on the establishment of a pan-Islamic caliphate and view the destabilisation of the formative Iraqi Government as fundamental to their agenda. They have been bolstered by a small but significant influx of foreign fighters. The Sunni extremists are very active in stoking the flames of self-sustaining sectarian violence by engaging in iconic and mass-casualty attacks and utilising tactics such as multiple suicide vests and vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs). Baghdad has borne the brunt of sectarian attacks because it is the centre of government and a target-rich environment.

Retaliatory attacks by Shi’a militias have been a hallmark of the violence throughout 2006, which increased significantly following the destruction of the ‘Golden Mosque’ in February. Jaysh al Mahdi (JAM) has been particularly active in killing Sunnis throughout Baghdad. It has used kidnapping and death squads to target Sunnis and intimidate their communities, and many of their target lists name members of the now defunct Ba’ath Party. Another Shi’a militia that has been very active in targeting the former regime is the Badr Organisation, which has been successful in infiltrating the Iraqi Government. Members of the former Ba’athist regime have now largely dispersed and joined groups termed ‘Sunni rejectionists’.

The Sunni rejectionists, such as the 1920s Revolutionary Brigade, have actively targeted the Multi-National Force in Iraq (MNF-I) and the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). Such groups are an embodiment of the dispossession felt by the Sunni community and joining them has given people a sense of purpose. Moreover, grievances felt by members have led them to support violence. An additional cause for concern is that many Sunni rejectionists have significant military expertise and interact with extremists to further their agenda of establishing a Sunni-dominated government. The Kurdish provinces in the north are reasonably stable due to effective policing by the Peshmerga militia, which acts as a guarantor for Kurdish autonomy. Still, this creates yet another factor in the complex cultural tapestry that is Iraq.

Militias continue to generate a climate of intimidation and disregard for the rule of law. Militia activities in the south are largely characterised by a Shi’a–Shi’a struggle for power and influence, with strong tribal influences. The south of Iraq has the least commonality with Baghdad and other regions as regards the nature of the struggle. However, attacks, particularly by JAM, continue on MNF throughout the southern provinces. Southern Iraq is a non-permissive environment for the staging and conduct of Sunni extremist and rejectionist operations, yet it still experiences the high levels of crime that are prevalent throughout the country.

Crime is a symptom of the economic malaise that has accompanied the instability and lack of security. Moreover, due to the very high levels of unemployment and lack of opportunities, the population has remained vulnerable to recruitment by criminal gangs and extremist groups who have been able to induce people to commit violent acts. In such circumstances, the offer of US$500 as payment to carry out an improvised explosive device (IED) attack against the MNF is very attractive when you have a family to support. A man may escort his children to school in the morning, conduct an attack and then return to collect them in the afternoon. Such an adversary blends into the local community because he is a member of that community.

Apart from economic deprivation, the dilapidated state of Iraq’s infrastructure was only fully understood when Coalition forces conducted assessments that exposed the enormity of the problem. Three examples serve to highlight this. Firstly, limited power generation and distribution grids mean that Baghdad receives about eight hours of electricity per day, and although transmission towers are attacked occasionally, the greatest danger is from high winds. (In addition, water pipelines and pumping stations also require significant attention, and communications towers have been targeted for destruction). Second is oil—the lifeblood of the Iraqi economy. It pumps along pipelines that regularly fail due to fatigue and the maintenance and repair of these economic arteries is hampered by security and environmental factors. Third, in addition to temperature extremes, the shifting sands reduce cross-country movement options, limiting the mobility corridors. Many rural areas in central Iraq have undulations, berms and canals with large date palm groves that provide suitable terrain from which to mount an ambush. These areas transition to an urban environment, where the traffic and bustle of everyday life provides effective cover for attacks, thereby complicating the Coalition forces’ ability to distinguish the enemy.

Difficulties in identifying the adversary can extend beyond local towns, with major cities providing a microcosm of the diversity in the country. These large urban centres also provide points of influence for those nations surrounding Iraq that sponsor and incite violence. Iran is an active sponsor of Shi’a militias. It provides munitions, finance and training to the militias, who remain embroiled in their ongoing conflict with the Kurds. In addition, Turkey maintains a close watch on northern Iraq while Syria facilitates the flow of fighters into Iraq across their permeable border. Iraq therefore represents an extremely diverse and complex warfighting scenario of which human organisations form the core. There are many interdependent variables that influence the effects of human interaction. A cycle of successive adaptations shape the current nature of the conflict. A systems analysis of Iraq would reveal that the country has reached ‘critical mass’ and is now self-sustaining: the feedback loops (such as economic dislocation, revenge and violence) continue to function without the initial stimulus.1 Iraq exhibits many of the attributes associated with the Australian Army’s Future Land Operating Concept, Complex Warfighting, such as threat diversity and lethality, urban environments, and complex physical, human and informational environments.2 Given the confused nature of conflict in Iraq, with asymmetric threats that require full spectrum operations, there remains little choice but to implement an EBO approach.

Effects-Based Operations

‘Effects-based operations’ has become increasingly popular as a description of the way in which military operations need to be conducted in the information age. At its core, EBO involves a whole-of-government approach, influencing the actions of an adversary through effects-seeking activities. The concept of using national power across the spectrum of conflict is not new, but it has rarely been successfully achieved. Indeed, the idea of an effects-based approach to warfare aligns easily with the theories of Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz and B. H. Liddell Hart, all of whom espoused the importance of the cognitive domain and the psychological dimension of war.3 A manoeuvrist approach, in which the aim is a massing of effects rather than the massing of force, has been a fundamental tenet of the Australian Army for many years.

Comprehending how information-age technologies and military force are integrated into the whole-of-government approach to conflict has been at the heart of the theories and discussions surrounding EBO. There has been an expectation that effective planning, using EBO as its base, enables the inclusion of second-and third-order effects in any action. However, warfare is characterised by chaos, and inferring that control can be exerted over a changing array of interdependent variables lacks logic. All actions and resultant effects are interrelated and, although the actions can be modelled, the exact way in which human beings will react to a situation, stimuli or action cannot be foreseen.

Effects cascade from causes or actions, and human decisions influence the flow of physical and psychological effects. One useful insight is the circumstances of, and following the death of Abu Musab al Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq. Zarqawi was an effective leader who was known as much for his brutality as for his effectiveness in rallying the Sunni extremists to his cause. He was in many respects a cult figure who attracted foreign fighters and funding to the jihadist cause, but he also alienated many Iraqis by kidnapping and murdering their fellow citizens. Zarqawi had a penchant for beheading people (including foreign contractors) and directed a large number of suicide attacks against Shi’a civilians—attacks which resulted in estrangement from those communities. Most importantly for the American-led Coalition, he was a terrorist and their ‘most wanted’ individual in Iraq.

An unedited version of a video produced by Zarqawi in April 2006 was captured by the MNF-I and used effectively by the Strategic Effects Communications Division to lampoon him for his poor weapon handling and artificial staging of events. It also provided clues as to his whereabouts. Information came to hand that Zarqawi was in Diyala Province to the northeast of Baghdad and, due to the lengthy time necessary to deploy forces, the decision was made to undertake precision targeting of the building in which he was meeting with other members of his group. The attack was successful and Zarqawi was killed by a US air strike on 7 June 2006; however, there remained intense speculation regarding what effect this action would have on al-Qaeda in Iraq.

Killing Zarqawi was an unqualified public relations triumph which reverberated positively around the world, removed a brutal killer and highlighted the continuing success of operations in Iraq. Another excellent outcome was the volume of information gathered from a ‘thumb drive’, other equipment and documents found with Zarqawi, which enabled the targeting of other al-Qaeda personnel. Speculation continued as to whether this operational success mortally wounded al-Qaeda in Iraq or whether it meant that the group would simply adapt and, if so, in what direction. Eventually a replacement leader—Abu Ayyub al-Masri—emerged to continue the al-Qaeda agenda of fomenting sectarian violence by targeting Shi’a civilians with mass effect attacks. Although al-Masri does not have the cult status of Zarqawi, there have been indications that he is not as divisive and that he has, in some respects, already had a unifying effect on the disparate Sunni extremists. The example of Zarqawi illustrates many of the strengths and weaknesses of EBO, in particular how the direct physical effect has unseen and unknowable second- and third-order physical and psychological consequences.

The physical action of killing Zarqawi removed the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, it disrupted the group’s operations and exacted a psychological effect on its members. Other effects included the positive influence on the global media—a good news story that provided a perception of success both in the ‘war on terror’ and the rebuilding of Iraq. In summary, the Iraqi Government was bolstered by the death of this feared and brutal extremist; and it captured documents that enabled the cascading into further physical effects, such as the targeting of other members in the group. In response, al-Qaeda in Iraq proved to be adaptive when a less divisive leader emerged who continued along the stated jihadist path in Iraq. Only time will tell whether these cascading effects can match the successful aftermath immediately following Zarqawi’s removal.

It is clear that this action had effects well beyond the battlespace in Iraq that resulted in a chain of unpredictable consequences. As the reaction of an adversary will cause effects, which in turn have their own consequences, it is impossible to predict the second- and third-order effects. Success, when dealing with complex adaptive systems, is achieved by being able to adapt quickly, and the application of EBO, in embracing the resultant chaos, can lead to a successful completion of the adaption cycle.

Adaptive Effects Approach

A military force must understand and learn from the complex war scenario and be able to complete the adaption cycle faster than its adversary. This is understood by the Australian Army, which has articulated a response to Complex Warfighting in the concept paper Adaptive Campaigning.4 An ‘adaptive campaign’ is defined as ‘actions taken by the land force as part of the military contribution to a whole-of-government approach to resolving conflicts’.5 The concept absorbs the fundamental tenets of EBO, acknowledges the diffused nature of conflict with regard to a temporal rather than spatial regard for intensity, and accepts that a myriad of (often-unexpected and unforeseeable) tasks must be completed during an operation. A battlegroup may be required to conduct combat, peace support or humanitarian tasks on the same day, so defining a conflict such as the one underway in Iraq via tasks is not useful. A more flexible and realistic approach lies in accepting the complexity of operations and being able to adapt rapidly.

In order for land force action to be successful, a battlegroup must be able to step rapidly through the ‘Act-Sense-Decide-Adapt’ cycle.6 An army must be able to adjust to the actions of the complex adaptive system that is the adversary in an ongoing process, with multiple courses of action developed to deal with new permutations of the threat.7 As humans make errors, the information will never provide perfect situational awareness. Given that an adaptive approach acknowledges that these errors occur and accepts that the battlespace is opaque, perfect EBO is never achievable and should not therefore be the aim.

During the past decade, considerable effort has focused on removing humans from the loop—the development of the sensor-shooter paradigm. This was a mistake. It was wrong to believe that the complexity of conflict could be overcome by removing people from the loop. Instead, the effort must concentrate on informing the decision-maker (the commander) so as to enable him to make the most appropriate decision in any complex environment.

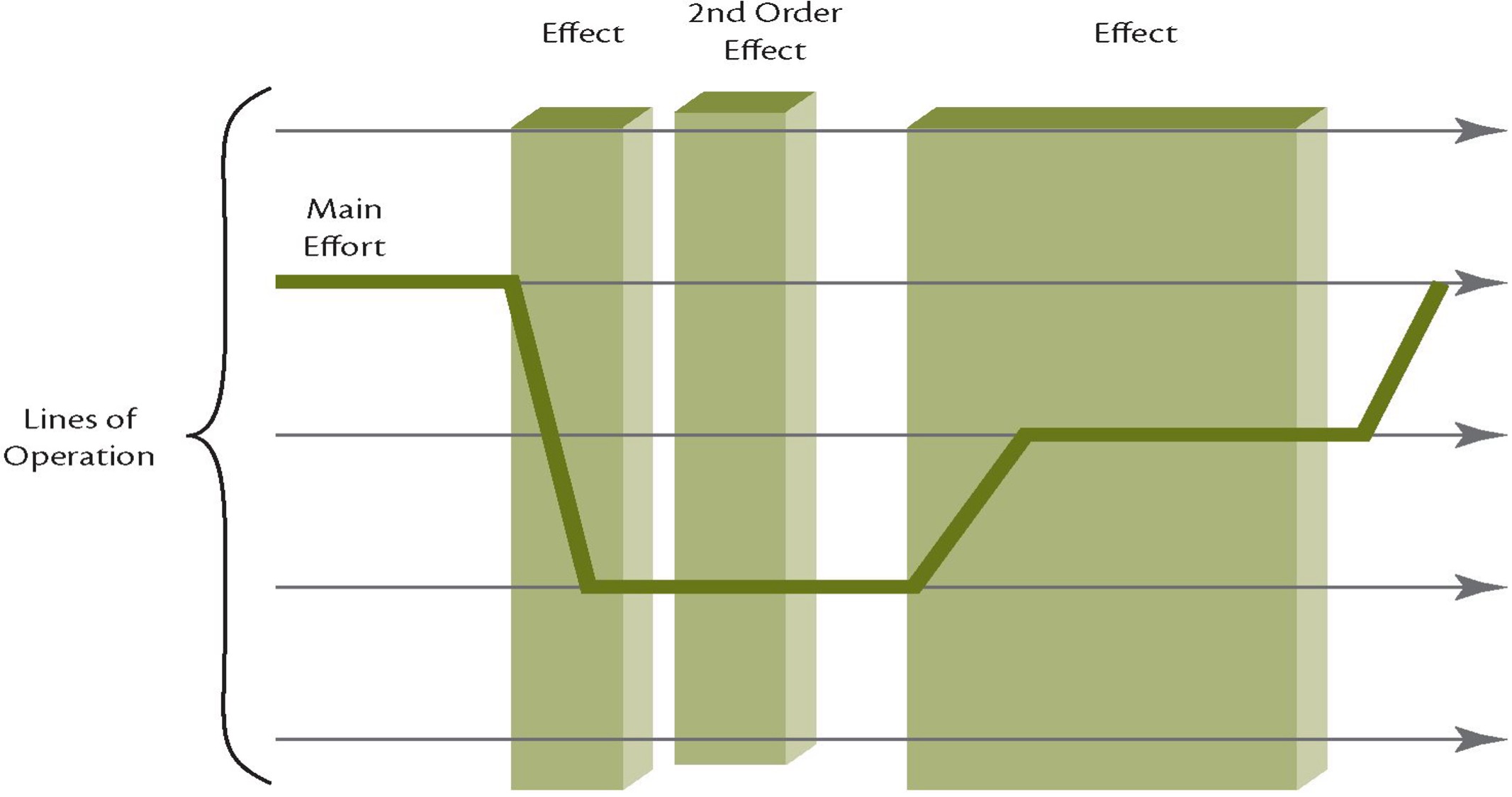

As clearly articulated in Adaptive Campaigning, the agility to switch between lines of operation is the key to successful prosecution of the complex fight.8 This agility requires flexible force structures, in the form of combined-arms teams, and highly-tuned situational awareness. There also needs to be a flexibility of thinking in the acceptance that switching between lines of operation is a natural evolution in the application of EBO (illustrated at Figure 1). As main effort is applied along a line of operation, the remaining lines do not disappear; rather they support it. When one effect is achieved, any second-order effect may require a switch in that main effort. Thus, the adaptive approach may require a sequence of switching in order to deal with cascading effects or to achieve a desired effect. A strong focus on mission command ensures that subordinate commanders have a clear understanding of purpose, and the initiative and ability to adapt to the second- and third-order effects generated by their actions.

In Iraq, there has been considerable criticism of the United States for failing to empower junior commanders, use options other than force, and nurture popular support.9 There is a strong inference that the United States was unable to switch between combat and other lines of operation that supported the population—that their elevated sense of moral righteousness and kinetic solutions, coupled with rigid structures, impeded operational agility. However, criticising the operations in Iraq ignores the tremendous success of many tactical actions and operations. Important lessons have been learnt and have led to an increased ability to adapt in any given conflict scenario.

Figure 1: Switching Main Effort between Lines of Operation

The interacting cycles of sectarian violence that peaked in Iraq during 2006, particularly in Baghdad, significantly impacted on MNF-I operational plans. The Baghdad Security Plan was enacted by the Force Commander to disrupt the selfsustaining violence that reflected a vicious feedback loop; however it did not result in the desired effect. Instead, the MNF-I hierarchy showed flexibility in adapting to the situation and modifying their operational planning. It recognised the need to account for adaptive adversaries in the form of Shi’a militias (such as JAM) and Sunni extremists (such as al-Qaeda in Iraq). The second iteration of the Baghdad Security Plan incorporated significant interaction with the community, ranging from rubbish removal to cordon and search activities, thereby demonstrating the flexibility to switch across lines of operation.

The Australian Battlegroup in Iraq

The Australian Battlegroup also needs to be adaptive in order to be successful in southern Iraq. It is responsible for conducting ‘overwatch’ activities in the provinces of Al Muthanna and Dhi Qar and is referred to as the Overwatch Battlegroup—West (OBG-W). To be successful in this role, the OBG-W needs to have an effects-based approach to their operations, as well as the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances. A typical operation may require the Battlegroup Commander and a combat team to conduct indigenous capacity-building activities by engaging the Iraqi leadership (for example, in visits to the Governor of Al Muthanna Province or the Brigade Commander of the Iraqi Army brigade responsible for the province). The Australian Army Training Team in Iraq is supporting such activities by building the professionalism and cohesion of the Iraqi Army. In so doing, it is nurturing civilian governance and strengthening the capabilities of the ISF.

These activities are supported in parallel by civil-military cooperation, which provides population support in the form of infrastructure such as bridges. Despite not being the main effort, it remains a supporting line of operation. Whilst conducting these engagement activities, the OBG-W is required to conduct protected mobility around the provinces. As such, it may need to switch instantly to a combat line of operation.

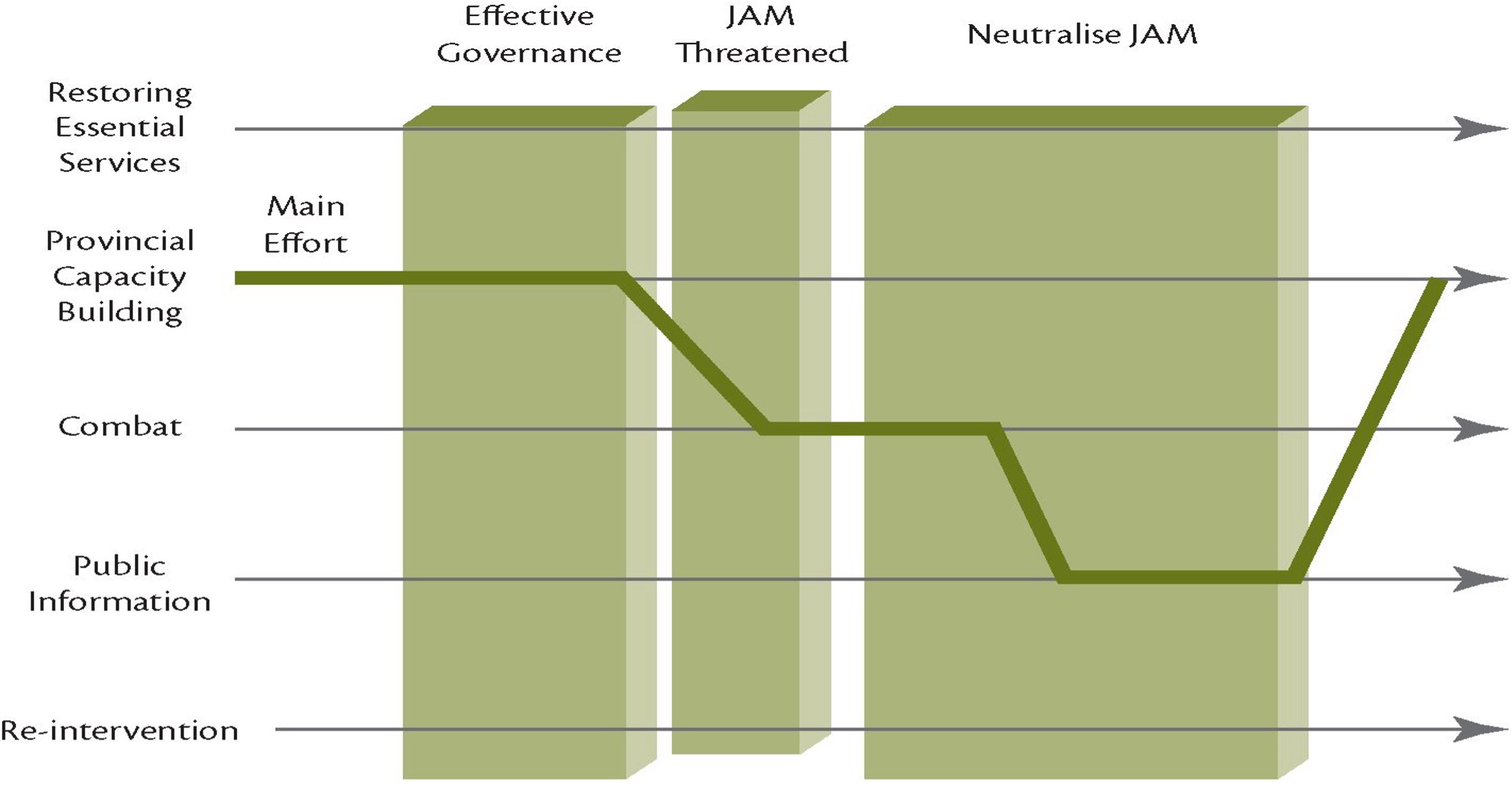

In late September 2006, probable JAM members, who were actively disrupting civilian governance and harassing the ISF to improve their own position of power, attacked a combat team from OBG-W. The incident occurred as a direct result of the success of OBG-W engagement activities, which had the second-order effect of prompting a violent reaction from this Shi’a militia group.

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction of switching main effort and effects. These effects had been considered as part of the operational planning, inclusive of reliable information available from human intelligence (HUMINT) which provided OBG-W with an awareness of the threat. Appreciating the human dimension of the Iraqi battlespace, by placing a priority on HUMINT rather than technological assets, has been of advantage to OBG-W when dealing with complex adaptive human systems. The Australian Army has an advanced HUMINT capability at work as part of OBG-W, and the intelligence generated primarily via this input, feeding into an effective analysis at Headquarters, has proved vital to the Battlegroup commander’s decision-making process and OBG-W’s application of force to successfully neutralise the threat.

Figure 2: Main effort switching and effects in Iraq

Once the desired effect of neutralising the threat in the Province has been achieved, the main effort can then switch to informing the population about the incident so as to contain any cascading effects that might arise following the deaths or wounding of militia members. This would involve talking to tribal sheikhs, the members of the Provincial Council and community contacts, as well as disseminating information to the population through psychological operations. Once complete, the main effort would then switch back to building the capabilities of the Province so as to ready the Iraqi people to govern themselves. The commander’s ability to adapt and switch between the lines of operation is at the heart of the philosophy required by the Australian Army.

Philosophy of the Adaptive Effects Approach

To be successful in a complex environment such as Iraq, those within the Australian Army must show flexible thinking, with commanders being required to adapt quickly, based on a firm adherence to mission command and iterative learning through constant operational assessment. Recognition that action is required, and that the effects of these actions probably cannot be predicted, means that all commanders must be able to adapt to the complexity of the situation once given a clearly articulated and understood purpose. The acceptance of chaos in the battlespace, and the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances, is fundamental in any successful approach to defeating the adversary.

Understanding the adversary as an adaptive human system, and comprehending the threat, relies heavily on advanced HUMINT and an awareness of the cultural terrain within which the force is operating. The cultural knowledge provides the context—a basis for the analysis of the situation. There must also be an ability to translate this information and intelligence into useful inputs for the commander’s decision-making. The commander is then well placed to adjust by moving rapidly through the adaption cycle and switching main effort across simultaneous lines of operation. This ability needs to occur from the combat team through to the task force and requires structural flexibility in order to enable the required agility.

Conclusion

The conflict in Iraq is a complex scenario with a multitude of situations that bridge the levels of intensity and merge previously partitioned tasks. The multifaceted threat has proven to be adaptive and very human in its mosaic of responses, approaches and agendas, as well as the variety of kinetic and non-kinetic effects it has employed. In many respects, this environment demonstrates the chaos of conflict and the enduring human nature of warfare. Acceptance of the human dimension naturally flows to the need for an effect as the outcome of operational activity. A bureaucratic, process-driven approach to EBO, where the cascading effects are painstakingly modelled to provide every conceivable option sequel and outcome, ignores the human dimension.

An adaptive effects approach accepts that not everything about the battlespace is known. This approach provides commanders with the agility of mind and structure to switch their main effort between lines of operation. It is fully inclusive of that human domain which is conflict. By embracing the complexity of human activities, a military force can adapt quickly and gain a successful outcome from complex warfighting.

Endnotes

1 David Kilcullen, Countering Global Insurgency, 2004, p. 31, available at <http://www.smallwarsjournal.com/documents/kilcullen.pdf>, accessed on 1 November 2006.

2 Department of Defence, Australian Army Future Land Operating Concept, Complex Warfighting, 2004, pp. 5–9.

3 Joshua Ho, ‘The Dimensions of Effects-Based Operations: A View from Singapore’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. II, No. 1, Winter 2004, p. 99.

4 Department of Defence, Australian Army Concept, Adaptive Campaigning (Draft), 2006, p. 3.

5 Department of Defence, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 4.

6 Department of Defence, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 7.

7 Edward Smith, ‘Effects-Based Operations’, Security Challenges, Vol. 2, No. 1, April 2006, p. 60.

8 Department of Defence, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 11.

9 Nigel Aylwin-Foster, ‘Changing the Army for Counterinsurgency Operations’, Military Review, Vol. LXXXV, No. 6, November–December 2005, p. 6.