Regime Change: Planning and Managing Military-Led Interventions as Projects

Abstract

While the experience in Iraq has generated a degree of political caution in the West towards mounting military-led interventions, it will inevitably only be a matter of time before fading memory and circumstances reverse this reluctance; this article offers a conceptual construct for such deployments. It first considers the nature of military-led interventions intended to effect regime change, and then develops a conceptual construct for reconstruction and societal reform that intervention forces can apply at the national, provincial and local levels of a society.

Western states now seem to generally accept that lasting security in their homelands requires proactive and sustained efforts abroad to prevent security threats emanating from unsatisfactorily governed locations.1 State governments that complicitly, or through their ineptitude, allow the export of violence and terrorism, illegal weapons (particularly weapons of mass destruction), illegal drugs and disruptive ideologies to the rest of the world must continue to be given the message that such activity is unacceptable. If such states are unwilling or unable to arrest these activities within their sovereign territories, then one can make a case to justify external intervention—potentially with the use of force.2 While the experience in Iraq has generated a degree of political caution in the West towards mounting military-led interventions, it will inevitably only be a matter of time before fading memory and circumstances reverse this reluctance.

Replacing an unsatisfactory government is a key objective in a military-led intervention in these circumstances, but there are often contributing issues that also demand attention. The success of any replacement government depends on the conditions achieved within that state. Intervention forces (those military as well as non-military agencies that establish a presence in the target state) may, therefore, become concerned with reconstruction and perhaps societal reform—activities associated usually with the term ‘nation-building’.3 This has been the case in Panama, Haiti, East Timor, Afghanistan and Iraq—states that had significant societal issues in addition to unsatisfactory governments.4 Indeed, the Bush Administration’s dismissal of deeper issues, its initial antipathy towards nation-building and the concomitant lack of preparatory organization for the post-conflict reconstruction of Afghanistan and Iraq explains, at least in part, why strategic victory in both remains elusive. We must accept, therefore, that effecting a ‘regime change’ will inevitably also require some degree of effort to reconstruct and reform other parts of that society.

Replacing an unsatisfactory government, then reconstructing and reforming a society from one condition to a better condition, is a complex, time consuming, expensive and difficult venture. It is important in light of recent regime change ventures to consider how future military-led interventions might be better planned and managed. Learning from history is valuable, and there has been a recent raft of books and articles about challenges and shortfalls in the case of Iraq.5 Given that every situation is unique, we must also consider military-led interventions in a generic conceptual sense. To this end, this article offers a conceptual construct for military-led interventions. It first considers the nature of military-led interventions intended to effect regime change, and then develops a conceptual construct for reconstruction and societal reform that intervention forces can apply at the national, provincial and local levels of a society.

On Military-Led Interventions

All of us know that to secure peace and protect the vulnerable, it is sometimes necessary to intervene, and in extremis to coerce.

- Javier Solana,

High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy,

Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union6

Military-led interventions initially and temporarily employ the military as a change agent (or catalyst) to enable the achievement of a higher political strategic objective. A victorious military force’s very presence conveys an authority and establishes the conditions whereby change in all aspects of society at least seems possible—particularly to the indigenous population. Soon after the apparatus of the unsatisfactory government or regime is defeated in a particular location, the indigenous population expects change, and intervention forces should, therefore, be prepared to commence local reconstruction and societal reform action immediately. Regime change, reconstruction and societal reform ventures demand an integrated effort by many different agencies. Inevitably, such ventures will also require the combined legitimacy and resources of a coalition of willing states and other non-state agencies.

When a political decision is made to conduct a military-led intervention, the military is typically assigned the leadership role for the first stage of the venture.7 Not surprisingly, the military instinctively views the activity through the lens of their own culture, and their relatively sizeable planning and organising capability generates a particular momentum, sometimes to the detriment of non-military considerations. While the prospect of imminent military action can draw people’s attention, such action is only a means to an end. The political masters who decide to unleash ‘the dogs of war’ retain responsibility to ensure that the military dimension of the intervention is integrated with broader non-military objectives and plans. Sometimes, however, these broader other-than-military objectives and plans are either non-existent, suffer from a lack of definition or organization, or are overly optimistic.8

In order to prevent the military from inadvertently, and perhaps inappropriately, steering the course of the venture, or worse, becoming committed to an activity with doubtful prospect of strategic success, a holistic approach is warranted. But how can the actions of many agencies from several states, as well as international non-state agencies, be effectively integrated towards achieving a common objective? And how can these actions be brought together to achieve the desired results? The military has well-developed doctrine to plan operations to defeat an opponent and remove the apparatus of an unsatisfactory government, but that doctrine does not apply equally well to meeting the subsequent reconstruction and societal reform requirements.9 I contend that a military-led intervention should be considered as an intervention project in which resources (including organizations and their actions, money and time) are integrated and optimized to achieve a defined objective.

Military-led Interventions as Projects

We have to start planning for wars within the context of everything else.

- Thomas P.M. Barnett, author and consultant10

Project management is a well-established discipline more commonly associated with building structurally complex systems.11 A society, though, is an interactively complex system in which the number of individual elements coupled with the degrees of freedom that each of those elements enjoys generates an almost infinite number of permutations. So, once begun, an intervention may proceed along any number of potential paths. It may even give rise to new groups that seek to resist and challenge the venture—witness those that have emerged in Iraq. While the direct result of any action by intervention forces can be predicted with some degree of confidence, this certainty diminishes rapidly for second- and subsequent-order results. Despite these challenges, I contend that a project management approach has great utility to holistically plan and manage interventions. Accepting this approach, plans for military-led interventions need to include the following features:

- A strategic objective that defines the desired result and subordinate objectives that contribute to the achievement of the strategic objective. All objectives must be defined, realistic, legally and morally legitimate and ideally agreed upon by all members of the intervention coalition.

- A holistic and comprehensive consideration of the target society. This analysis will involve a breaking down of the intervention project into societal sectors, each with its own reconstruction or reform objectives. It is vital to recognize that the target society is an interactively complex system and that the reform sectors are ultimately all linked. The plan must identify these links and anticipate that actions in one sector may also have an effect in other sectors.

- An ability to manage the conduct of the intervention. This involves the means to assign responsibility to agencies and apply resources to regulate the pace of efforts in each reconstruction and reform sector relative to others such that the results in each are integrated to achieve the strategic objective.

- An ability to adapt to a changing environment with identified alternate ways to achieve objectives within each reconstruction and reform sector. The changing environment potentially includes an evolving strategic objective—particularly as this environment strains the will and resources of the coalition partners. In the event, the intervention force has to adopt these alternate ways, each of these ways require contingency resourcing.

We will now consider each of these features in more detail.

Strategic Objective

The object in war is to attain a better peace - even if only from your own point of view.

- Basil Liddell Hart, Historian12

An intervention force’s generic strategic objective is to reform a target state such that its new indigenous government can independently exercise sovereignty to a standard acceptable to the coalition—that is, to be a viable, effective, and responsible member of the global community of states. For a particular military-led intervention, the strategic objective should be fully described with a series of attendant conditions. It may be difficult to achieve complete agreement on the strategic objective among all members of the intervention coalition but investment of effort prior to the start of the venture builds a sense of ownership and commitment across the coalition. Given the interactively complex nature of the environment, it should also be anticipated that the strategic objective might evolve throughout the course of the intervention. The degree to which the strategic objective evolves directly impacts on the legitimacy of the intervention and the coherence of the intervention coalition.

Reconstruction and Reform Sectors and Objectives

We need to morph the battlefield into a lasting political victory.

- Admiral (Retired) Arthur K. Cebrowski,

former Director of the Pentagon’s Office of Force Transformation13

Organizing any complex project is ultimately a balance between the way it is broken down into smaller parts and the way these smaller parts are brought back together to form the whole. The key is to align this process of organization with the application of logic, and more significantly the authority for action as well as the responsibility and accountability for results.

The US National Strategy for Victory in Iraq, released in November 2005, provides an insight into the challenges of organizing and managing a large-scale reconstruction and societal reform project. The document clearly articulates the strategic objective and then defines three tracks—political, security and economic.14 It characterizes these three tracks as ‘mutually reinforcing’ and asserts that they are integrated but it does not describe any linkages between tracks. In an effort to articulate how to implement the strategy, the document additionally identifies eight strategic pillars.15 The document states: ‘To organize these efforts, we have broken down our political/security/economic strategy (tracks) into eight pillars or strategic objectives.’16 Yet this conjunction implies that these strategic pillars are also strategic objectives that the three tracks are moving through or towards. The document then states that each strategic pillar contains at least five lines of action, each with ‘scores of sub-actions with specific objectives.’ The document continues further, stating, ‘Underlying each line of action is a series of missions and tasks assigned to military and civilian units in Iraq.’ Yet there is no description or diagram in the document that depicts the relationship between the tracks, strategic pillars, lines of action and underlying missions and tasks. Clearly, this venture is a complex arrangement. While the document may simply be serving as a public communication tool, it would do well to clearly explain how all this activity is going to be integrated to achieve the strategic objective—if, indeed, such a holistic plan exists.17

One of the most significant challenges in planning and managing an intervention is that of perspective; specifically determining what reconstruction and reform is needed and what sectors should be defined. The organizational structure of the government of the coalition’s lead nation tends to strongly influence the character of plans that intervention forces have developed to date. Reflecting a sense of the lead nation’s innate value, intervention plans have therefore tended to reflect the environment and organization of that nation—which is not necessarily appropriate where the prevailing societal conditions in the target state are significantly different. Furthermore, conducting these ventures is not just about which government department from the lead nation has the lead at any particular stage. In fact, the planners must objectively consider the venture with the perspective of the target state’s indigenous population uppermost. The formation of an intervention coalition provides an opportunity to plan and implement an intervention with more objectivity and reduced influence from the organizational structure and interests of the government of the coalition’s lead nation.

United Nations (UN) peacekeeping or humanitarian missions are military-supported interventions vice military-led interventions, yet they can offer an insight. When the UN plans and conducts peacekeeping missions, it typically establishes a number of ‘pillars’. Historically, the pillars of UN mounted missions have been governance, security, humanitarian aid and development. The civilian mission commander (and his or her staff) assigns responsibility for the pillars to subordinate organizations and co-ordinates the efforts in each pillar. The governance pillar typically consists of UN civil servants, but the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe is presently responsible for this pillar in Kosovo. The security pillar is typically the responsibility of a military force. The military element creates a more secure environment that allows the other pillars to achieve their objectives. One of the UN agencies, such as the UN High Commission for Refugees or the UN Development Programme, typically leads the humanitarian aid and development pillar. The needs of the particular situation dictate the pillars created. While the military-led interventions that the West might mount in the future may be more challenging than military-supported UN peacekeeping missions, the pillars approach as a conceptual construct and the alignment of an organization against each pillar is instructive.

In a similar vein, military planners have developed a broad range of conceptual tools to design military operations. One of these tools is a concept called a ‘logical line of operation’.18 A logical line of operation (LLOO) links a series of ‘actions’ or ‘results’ in the most appropriate sequence to achieve an objective. Elements within the military organization undertake actions. These actions seek to achieve results in the environment external to the military organization. A military plan that utilizes LLOO should link either actions or results—but not both. If a plan articulates both actions and results in the same context, the ability to match or correlate organizational actions with environmental results is reduced. A more sound approach is to have a plan that defines results, supported by a series of subordinate plans detailing the corresponding actions required to achieve those results. Ideally, the plan assigns each LLOO to a single organization that has the authority for action as well as the responsibility and accountability for results.

When military plans (or plans influenced by military planners) seek to address more than the military dimension, the LLOOs used have tended to be derivatives of the instruments of national power. The United States uses the DIME (diplomatic, information, military and economic) model to describe the elements of national power, while the United Kingdom uses DME (underpinned by the I that is explicit in its US equivalent). Using the instruments of national power as LLOO reflects the internal organization of the intervening state or coalition, not the nature of the target state or the reforms required. Thus, this approach tends to emphasize actions rather than results. It has, however, enabled the military to align itself with the military dimension and create the expectation that other agencies accept responsibility for the other LLOO. In recognition of a tendency to emphasize action rather than results, there has been a progressive evolution of LLOO from a basis in the instruments of national power towards grounding in broader societal constructs.19 Several paradigms developed within the military using acronyms such as PMESII (political, military, economic, social, infrastructure and information), ASCOPE (area, structures, capabilities, organizations, people and events) and MIDLIFE (military, information, diplomatic, law enforcement, intelligence, finance and economic), while designed for analyzing a problem or society rather than reforming it, have evident utility as potential LLOO for military-led interventions.

Outside of the military and focusing on post-conflict environments, the US Department of State’s Office of the Co-ordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization has identified five ‘technical areas’ of reconstruction’s essential tasks: security, governance and participation; humanitarian assistance and social wellbeing; economic stability and infrastructure; and justice and recon- ciliation.20 In Losing Iraq - Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, David Phillips proposes the following ‘focus areas’: humanitarian relief, transitional security, rule of law, infrastructure reconstruction, economic development and political transition.21 From a slightly nuanced perspective of nation building, the RAND Corporation identified the following ‘key areas’: security, health/education, governance, democratization, economics and basic infrastructure.22 Additionally, the role the private sector plays in contributing towards the achievement of the strategic objective is becoming more evident from the experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan.

These ‘pillars’, ‘LLOO’, ‘technical areas’, ‘focus areas’ and ‘key areas’ are divisions used to enable a conceptual breaking down of the venture. While the use of any divisions is inherently artificial given the interactively complex nature of a society, some division is necessary in order to align responsibility with different agencies in the intervention force.

For the purpose of this paper, therefore, I will use the term reconstruction and reform sectors on the basis that different sectors will need different combinations of reconstruction and reform action. But what set of reconstruction and reform sectors has the most utility for the conduct of a military-led intervention? On balance, the logical seams suggest that there are five reconstruction and reform sectors that should guide planning for a military-led intervention as follows:

- Public Governance. This sector includes the reform of all government responsibilities and institutions as well as the policies that set the conditions for the other sectors—particularly the private commercial sector. The public governance sector also includes the involvement of the population in the political process.

- Public Security. The public security sector includes the constabulary (police, border security and customs) and military elements of a state.23 The military stage of the intervention establishes the public security environment that enables reconstruction and reform in all of the other sectors. The failure to achieve minimum acceptable levels of security will preclude other non-military agencies from commencing action in other sectors.24 In this situation, the military is sometimes drawn into performing actions in other sectors— actions for which it is not necessarily designed or trained. The military’s primary objective, therefore, is to create a level of public security that will allow, and in fact encourage, other agencies to be able to commence work and to persevere unhindered in other reconstruction and reform sectors. The objective within the security sector is to create an enduring indigenous capability to maintain minimum acceptable levels of public security. This sector is conceptually part of the public governance sector, but is initially separate because the military force establishes it before any action can commence in the other reconstruction and reform sectors. Additionally, the new indigenous government will take some time to form and develop the capacity to take on authority and responsibility for the public security sector.

- Public Infrastructure. The intervention force must repair the damage caused by the military stage of the intervention and be seen to be making a material difference that validates the removal of the previous government. Reconstruction and reform in the public infrastructure sector is an essential enabler to progress in other sectors—particularly the private commercial sector. At some stage in the venture, certain aspects of the public infrastructure sector may develop in conjunction with the private sector in public-private partnership activities.25 Like the public security sector, the public infrastructure sector is also conceptually part of the public governance sector, but because the new indigenous government will take some time to form and develop the capacity to take on authority and responsibility for this sector, it is also initially separate.

- Private Commercial. The enabling conditions for enhanced private commercial activity include minimum acceptable levels of public security, sound government institutions and policies, and adequate public infrastructure. When the intervention force achieves these enabling conditions, the private commercial sector can generate significant momentum for broader societal development. Foreign direct investment and trade are key features, and an effective taxation system enables the state to become viable in the long term. The objective in this sector is to create a self-sustaining market-based economy.

- Social. Reform of certain aspects of the target society’s culture may be required to include reducing the influence of detrimental concepts (such as an unsatisfactory political ideology or corruption) or by inculcating certain positive concepts (such as democracy and the rule of law). This sector may also include a social reconciliation process if parts of the indigenous population feel disenfranchised.

These five reconstruction and reform sectors reflect the fact that once the initial military stage of an intervention is complete, an intervention focuses on the public (civil) sector. The intervention force must plan, resource and organize to commence action in each of the five reconstruction and reform sectors well ahead of the military stage of an intervention so that physical action in each sector can commence on the ground as soon as possible.

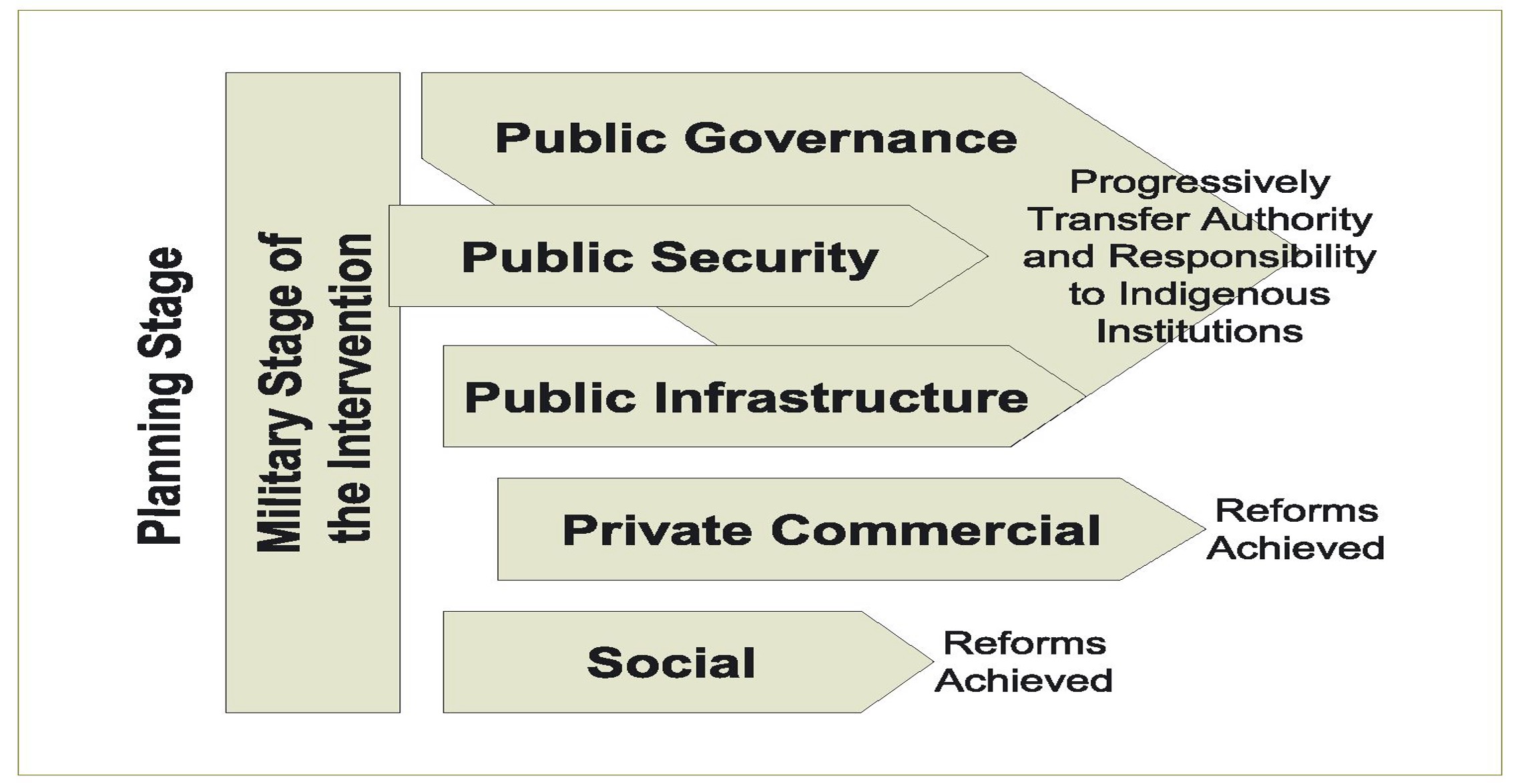

Figure 1

Figure 1 depicts an intervention project and shows the military stage of the intervention and the five subsequent reconstruction and reform sectors and their inter-relationships. The figure shows how the military stage of the intervention directly creates the public security environment that enables action in the other four sectors to commence. Of the five sectors, the public governance sector is likely to be the most challenging, as ultimately, the indigenous government has to have full authority for all aspects of sovereignty. Thus, as the public governance sector strengthens and the indigenous government develops its capacity to govern, its mandate progressively expands to include taking on responsibility for the public security and public infrastructure sectors—although not necessarily in that order.

The public governance sector includes efforts to develop policy and laws that establish the environment for the private commercial sector. The coalition’s efforts in the private commercial sector are oriented towards getting the national economy to a position where it becomes self-sustaining. As states with market economies mature, they strive to maximize the private sector and minimize the public sector. A similar trend applies to an intervention project. Therefore, the relationship between the public governance sector and the private commercial sector needs close management. Achieving the desired social reforms may take a relatively short period or it may take several generations. If social reforms are the last remaining sector that the intervention force is working, then the public governance sector also assumes authority and responsibility for it in order to allow the intervention project to be terminated. When the intervention project is terminated, the target state continues to interact normally with the rest of the world.

Managing the Conduct of the Intervention

Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the managers of war.

- Paul Cornish, academic26

The argument so far indicates that, taking from the project management discipline, the intervention coalition should appoint an intervention project manager. The project manager should be responsible to the owners of the project—that is the states and other non-state agencies of the intervention coalition, who are in turn responsible for providing the resources the project manager identifies.27 While the project manager will most likely be a citizen of the coalition lead-nation, representatives from all coalition states and agencies, to include both the public and private sectors, leaven the project manager’s staff. The project manager identifies those agencies best suited to take on the responsibility for the military stage of the intervention and each of the five reconstruction and reform sectors. The project manager supervises action in the military stage of the intervention and across the five sectors, but more importantly, integrates the results achieved in each. The project manager decides when the indigenous government has the capacity to take on responsibility for the public security and public infrastructure sectors. To carry out this array of tasks, the project manager must be given a degree of authority over each of these agencies—particularly over the military forces conducting the military stage of the intervention and responsible for the public security sector.

Beyond the question of authority, for the project manager to be most effective, the intervention plan must identify the desired results or objectives in each reconstruction and reform sector. The agency responsible for each particular sector then determines the actions required to achieve those objectives. Once the strategic objective and subordinate objectives within each reconstruction and reform sector are determined, it should be possible to identify a critical path—that is, the path of results or subordinate actions that is most limited by the available resources. Often, the public governance sector will require the most time—especially if there is a lack of sufficiently educated indigenous people to become the civil servants that operate government institutions.

The society of a target state is unlikely to perceive that it requires reform and the intervention coalition must strive to convey to them a positive message. Use of the terms ‘reform’ and ‘intervention project manager’ may be inappropriate. The intervention project manager’s leadership role and his or her authority for the venture also require emphasis. Indeed, as with any venture, leadership, transparency and relationship building will also be important to the success of the activity. The title, ‘Transition Authority Leader’ may be acceptable to all parties—particularly the indigenous population of the target state. Identifying the right person for this appointment is clearly important.28 The Transition Authority Leader and his or her staff should establish their offices in the capital city of the target state as soon as practicable. The Transition Authority Leader’s moral authority remains high if the strategic objective is defined, transparent and clearly communicated to the indigenous population. When the intervention force achieves the strategic objective, the intervention coalition dismisses the Transition Authority Leader and disbands the intervention force.

Adapting to a Changing Environment

Whosoever desires constant success must change his conduct with the times.

- Niccolo Machiavelli29

All plans require a degree of built-in flexibility and this is especially true for a complex and potentially evolving project such as a major reconstruction and societal reform venture. The Transition Authority Leader needs to be responsible for managing the pace of achieving results in each of the reconstruction and reform sectors so that they become mutually supporting towards achieving the strategic objective. In order to develop an ability to adapt to a changing environment, each reconstruction and reform sector must seek to anticipate potential changes and identify alternate ways to achieve its objectives. If adopted, each of the identified alternate ways must be feasible, acceptable and able to be resourced. The changing environment may also bring about an evolving strategic objective—particularly as the will and resources of the coalition partners are strained. The responsibility for managing this circumstance rests on the Transition Authority Leader and his or her ability to interact with the intervention coalition.

A Nested Application

As soon as the military force removes the apparatus of the unsatisfactory government, action must commence in each of the five reconstruction and reform sectors. Successive transitions at the local level contribute to provincial level transitions and ultimately lead to a transition at the national level. Thus, the conceptual construct of a military stage followed by five reconstruction and reform sectors, as well as the appointment of provincial and even local Transition Authority Leaders, applies at multiple levels in an intervention project.30 As the patchwork of locales where the military stage of the intervention transitions to the reconstruction and reform stage, those agencies responsible for each of the reconstruction and reform sectors must progressively expand and integrate their actions. Co-ordinated effort at the local level is especially important where direct contact with the indigenous population occurs and actions with tangible results have the most impact.

Conclusion

The replacement of an unsatisfactory government by a military-led intervention will inevitably require some degree of effort to reconstruct and reform other parts of the society of the target state. Military-led interventions initially and temporarily employ the military as a change agent (or catalyst) to enable the achievement of a higher political strategic objective. This paper considers a military-led intervention to effect regime change as an intervention project in which resources (including organizations and their actions, money and time) are integrated and optimized to achieve a defined objective. The use of a project management approach enables a more objective and holistic approach to planning and managing military-led interventions. This article offers a conceptual construct to plan and manage interventions with the appointment of a Transition Authority Leader as project manager who is responsible for integrating the results of the military stage of the intervention and of five reconstruction and reform sectors: public governance, public security, public infrastructure, private commercial and social. Intervention forces can concurrently apply this construct at the local, provincial and national levels of a society.

Endnotes

1 The term ‘unsatisfactorily governed’ is deliberate. Unsatisfactory state governments include weak or failing state governments as well as ‘tyrannical’, ‘rogue’ or ‘aggressive’ governments. Any definition of what constitutes unsatisfactory governance will be contentious. An objective measure is probably impossible and any definition will often be subject to particular interests. The UN Security Council and other multilateral intergovernmental bodies will play a role in making such determinations.

2 The West has an interest in maintaining a Westphalian-based order in which states are the principal geopolitical actors. While some argue that sovereignty and societal organization along a state basis are dated or redundant concepts, in the absence of established and successful alternatives this paper will assume that these two concepts will continue to remain relevant for the immediate future.

3 For the purpose of this paper, a society is a definable group of human beings and the tangible and non-tangible elements that make that group distinctive.

4 For a synopsis of these examples and others see Francis Fukuyama (ed.), Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2006.

5 See for example David Phillips, Losing Iraq – Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 2005, or Michael Gordon and Bernard Trainor, Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq, Pantheon, London, 2006.

6 Speech to the 40th Commander’s Conference of the German Bundeswehron 11 October 2005. See <www.ue.eu.int/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/dlscours/86523.pdf>, accessed on 16 February 2006.

7 Given that other non-military leverage to achieve objectives may still be pursued, while preparations are made for a military-led intervention.

8 An example is the US Department of State’s Future of Iraq Project that produced a large volume of information on requirements and recommendations but no clear objectives or plan that intervention forces could action. The issue became moot, however, when the US Department of Defense’s Organization for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance largely ignored the project’s work. See Philips, Losing Iraq; Mitchell Thompson, ‘Breaking the Proconsulate: A New Design for National Power’, Parameters, Winter 2005-2006, pp. 68-70; and Gordon and Trainor, Cobra II, p. 159.

9 Western military operations planning is conceptually based on identifying enemy Centers of Gravity on the presumption that their destruction or defeat will consequently achieve the objective or bring about the desired end state. For an excellent critique, see Pierre Lessard, ‘Campaign Design for Winning the War... and the Peace’, Parameters, Summer 2005, pp. 36-50.

10 <http://www.thomaspmbarnett.com/pnm/conversation.htm>, accessed on 25 February 2006.

11 Note that the definition of a ‘system’ is arbitrary. A system is simply a collection of components that have elements related in some way.

12 Basil Liddell Hart, Strategy, revised second edition, Meridian, London, 1991, p. 353.

13 <http://www.fletcherconference.com/oldtranscripts/2003/cebrowski.htm>, accessed on 25 February 2006.

14 These tracks are very similar to the diplomatic, military and economic instruments of national power. Interestingly, the document omits the information instrument despite the recent emphasis on public diplomacy and strategic communications within the US Government and a perception that the Global War on Terrorism is essentially a war of ideas.

15 These eight strategic pillars are: defeat the terrorists and neutralize the insurgency; transition Iraq to security self-reliance; help Iraqis form a national compact for democratic government; help Iraq build government capacity and provide essential services; help Iraq strengthen its economy; help Iraq strengthen the rule of law and promote civil rights; increase international support for Iraq; and strengthen public understanding of coalition efforts and public isolation of the insurgents. National Security Council, National Strategy for Victory in Iraq, November 2005, pp. 25-6. The strategy also describes a differently articulated strategic objective for each of these strategic pillars in the appendix of the document. National Security Council, National Strategy for Victory in Iraq, November 2005, pp. 28-35.

16 Ibid, p. 25.

17 The use of this example does not imply that the US strategy for victory in Iraq is flawed or not achieving its strategic objective, just that organizing a reconstruction and societal reform venture is a complex activity.

18 A logical line of operation equates to a conceptual line of operation.

19 See for example an article by Major General Peter Chiarelli and Major Patrick Michaelis, ‘Winning the Peace – The Requirement for Full Spectrum Operations’, Military Review, July-August 2005, pp. 4-17. <http://usacac.leavenworth.army.mil/CAC/milreview/download/Engtish/JulAu…;, accessed on 24 February 2006.

20 US Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization, Post Conflict Reconstruction Essential Task Table, 15 April 2005. See <http://www.state.gov/s/crs/rls/52959.htm>, accessed on 19 February 2006.

21 Phillips, Losing Iraq, p. 226.

22 Seth Jones, Jeremy Wilson, Andrew Rathmell, and Jack Riley, Establishing Law and Order After Conflict, RAND Publications, Santa Monica, CA, 2005, p. 11.

23 An excellent reference for reform in the public security sector is Jones et al, Establishing Law and Order After Conflict.

24 A level of security as perceived by the organizations responsible for action in the other reform sectors.

25 Afghanistan is now using this approach albeit four years after the intervention began. See <http://usinfo.state.gov/sa/Archive/2006/Jan/30-583095.html>, accessed on 19 February 2006.

26 <www.nato.int/acad/fellow/99-01/cornish.pdf>, accessed on 22 February 2006.

27 Resource donors are not limited to the states of the Coalition, and organizationally the project management team would perhaps require a section to coordinate resource contributions.

28 I don’t ascribe to the view that ambassadors make effective nation-builders. While the ability to communicate with the stakeholders and see different perspectives, there is little in a diplomat’s traditional career path that would develop the range skills required of a Transition Authority Leader. Some military leaders have proven adept nation-builders in the past, but in the modern information-economic driven era I suspect that Chief Executive Officers of large complex corporations might be the best area to find a Transition Authority Leader.

29 <http://www.leadershipnow.com/changequotes.html>, accessed on 25 March 2006.

30 This approach is similar to the Provincial Reconstruction Team organizational framework that has evolved in Afghanistan and is planned for Iraq.