Are You Teaching Me What I Need To Learn? Assessing Army Reserve Officer Training from a Staff Cadet’s Perspective

Abstract

As our modern army is called upon to operate in complex battlespaces against non-traditional enemies, or to undertake activities other than traditional warfighting, is the training provided to Staff Cadets applicable to the situations junior commanders will face in their future careers? This article assesses the Part Time General Service Officer First Appointment Course and highlights possible changes that would make it more relevant to the challenges facing junior officers today.

It is 1130 hours, slightly chilly, with a mild breeze. To my front, about 200 metres away across open ground, is the objective—a farmhouse located in approximately 100 square metres of medium vegetation. Running off to the right of the farmhouse, perpendicular to my current axis, is a creek line surrounded by light vegetation (in the form of thirty metre-tall gum trees). About 200 metres to my right—or so my map says, I have not yet been able to ‘do a recce’—is a disused quarry that could potentially conceal my platoon’s movement to the creek. To my left is more open ground and, although it is undulating and could potentially provide some cover on the approach to the objective, it does not immediately endear itself to me. About a kilometre beyond the objective, across even more open ground, is a tree line, which is the start of a medium-to-dense gum forest.

So why is this farmhouse my objective? Let me start with the bigger picture. A few weeks ago, the Musorians1 invaded northern Australia and began moving rapidly south towards the ‘boomerang coast’. They have moved so rapidly across Australia’s arid interior, however, that they have overstretched their supply lines and thus have been forced to temporarily adopt a defensive posture while they wait for their supporting elements to catch up. In order to take advantage of the situation, Australian forces have launched a new offensive—which is where I come into the picture. The farmhouse and the surrounding vegetation is an enemy position, the lead element of a Musorian motorised battalion. Intelligence confirms that somewhere in the gum forest a kilometre beyond the farmhouse is the lead company of the same battalion. In accordance with their doctrine, to which they tend to adhere rigidly, a squad-sized observation post has been established to the front of the position as early warning. My mission is to conduct a platoon attack against the observation post and clear it of the enemy.

Of course, the scenario given above is fictional, written purely for the purposes of this paper; although importantly it does mirror actual training scenarios I have encountered. What would happen next, were the above scenario real, is that I would begin to conduct the individual military appreciation process (IMAP). After having gone through this process, the end result should be a fairly sound plan of attack against the enemy position. This is the level of proficiency a Staff Cadet should have attained by the time they near the end of the Army Reserve Officer training program (officially the ‘Part Time General Service Officer First Appointment Course’; hereinafter referred to as either the PT GSO FAC, or simply as ‘the course’).2 By the final stages of the course a Staff Cadet should be familiar with the IMAP, with Australian forces (both those under their direct command and the supporting assets that may be at their disposal) and with the Musorians and their military doctrine.

Is this the information a Staff Cadet needs to know in order to graduate from the Royal Military College (RMC) fully prepared to undertake their role as a platoon commander in the modern Army Reserve? Establishing an answer to this question is my intent in this paper, although I am aware of the constraints I face in reaching an accurate answer—I am an Army Reserve (very) junior officer with no operational experience. What I do have, however, is access to a wealth of material that enables me to learn from the experience of others, which I will draw upon throughout this piece in order to substitute for the gaps in my own experience. Hence, this paper consists of three sections. Firstly, an overview of the current structure of the PT GSO FAC is provided for the benefit of readers who may not be familiar with it. This is followed by a brief discussion of the tasks and challenges facing the contemporary junior commander. Drawing on the conclusions reached in this discussion it becomes obvious that, despite containing several relevant training components, there are also a number of areas in which the PT GSO FAC may be improved in order to better prepare today’s Staff Cadets for the challenges they are likely to face as junior commanders. Discussion in the third section of this paper highlights six of these areas, along with the inclusion of some suggestions regarding possible ways to improve the course.

The PT GSO FAC Syllabus3

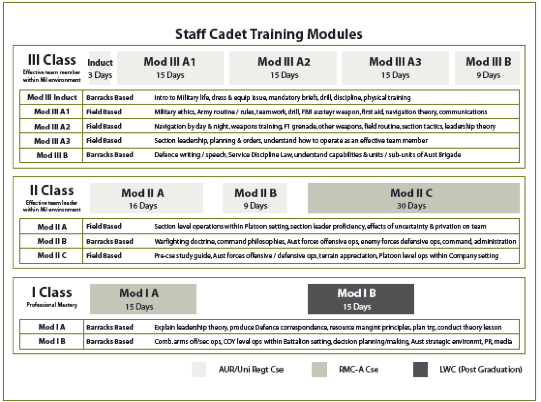

Like its full-time equivalent, the PT GSO FAC is divided into three ‘Classes’: Third, Second and First. Within each Class, training is further broken down into ‘modules’ of one or two weeks, which allow the Course to be undertaken in several short blocks (see Figure One). Cadets are generally allowed up to three years to complete all required modules and graduate from RMC; due to the times of year when each module is conducted, the minimum period over which training may be conducted is fourteen months, however this rate of completion is rare and Cadets usually finish the course over a period of approximately two years.

Third Class Cadets begin their training where everyone else in the Army does: learning the basic soldierly skills. During their initial modules Cadets are assessed on a range of skills including field craft, navigation, weapon handling, teamwork, first aid and infantry-minor tactics at the individual level (most of the learning objectives for these modules are similar to those taught at the Army Recruit Training Centre – Kapooka). This aspect of the course is conducted over four modules—three two-week blocks of field-based training and a one-week block of barracks-based training wherein Cadets are taught the basics of Army administrative procedure.

On progression to Second Class, Cadets attend one two-week module of field-based training, where they are assessed in the role of section commander, and one nine-day module of barracks-based training that concentrates on teaching Cadets the ‘fundamentals of land warfare’ as defined in LWD-1.4 Throughout their training, Third and Second Class Cadets are also progressively taught about the Musorians—firstly about their squad and platoon compositions, then about their battalion and brigade structures, and finally about their military doctrine. This is an important component of the course, as the Musorians are ‘the enemy’ that Cadets train against throughout the course.

Once these training courses have been completed, the final modules of the PT GSO FAC are conducted at RMC Duntroon over a continuous seven-week period. Assessment for this component of the course includes demonstrating competence as a platoon commander in the field and conducting tactical exercises without troops (TEWTs)—this paper’s opening scenario is similar to those that may be encountered in a typical TEWT. Once these final modules are completed, Cadets graduate from RMC at the rank of Second Lieutenant. A further sixteen-day training module is required prior to promotion to Lieutenant and corp-specific training modules are generally a prerequisite for obtaining an operationally deployable status.

Figure One. Army Reserve Staff Cadet Training Modules.

Source: Army Reserve Recruiting Material

The Tasks and Challenges Facing the Contemporary Junior Commander

Leaving aside the day-to-day personnel management tasks that are inherent to any management position, military or otherwise, defining the tasks and challenges facing the contemporary junior commander may at first glance appear simple. To some extent this is true—at the most basic level the role of the junior commander remains unchanged from ages past: the junior commander is given a mission and must lead troops towards the goal of completing it. The ‘principles of leadership’ also remain largely untouched.5 What has changed dramatically over the past few decades, however, is the nature of the missions that junior commanders are likely to be tasked with and the environment in which they must be achieved. Largely, this shift is due to a broader shift in the nature of contemporary conflict—a shift that warrants further examination.

The first significant contributing factor to this shift is that contemporary conflict is likely to manifest itself differently today than twenty years ago, when the possibility of large-scale conventional warfare in Europe was most likely. Even Australia, isolated from Europe by its geography, prepared to fight a large scale conventional war—the 1986 ‘Dibb Report’ (on which the 1987 Defence White Paper was based) asserted that:

Australia faces no identifiable direct military threat and there is every prospect that our favourable security circumstances will continue ... It would take at least 10 years and massive external support for the development of a regional capacity to threaten us with substantial assault.6

Despite the admission that ‘Australia is one of the most secure countries in the world’,7 the Australian Defence Force (ADF) was geared toward continental defence against the prospect of a large-scale conventional invasion, which may have originated somewhere to Australia’s north.

In contrast, Australia’s security environment today is far less benign. The Australian Army, which in 1986 had not undertaken a major overseas operation since the Vietnam War, is today involved in four: Iraq, Afghanistan, East Timor, and Solomon Islands.8 Furthermore, each of these operations is unique in nature, meaning that success in each requires an inherently more flexible Army than that of twenty years ago. This need for flexibility has been accompanied by a broader variety of threats to Australian security that mean the military can no longer solely prepare to protect the Australian continent from a ‘substantial assault’ by a conventional force. Instead, it must be prepared ‘to protect and defend our people, and our interests, and our way of life ... well beyond our shores’.9 This shift in Australia’s security strategy has necessarily resulted in a shift of focus within the Army, towards expeditionary operations both within Australia’s immediate region and around the world.

In addition to Australia’s strategic shift of focus, tactical requirements have also changed substantially over the past twenty years. Despite the plethora of different (and often competing) theories offered during the 1990s and early 2000s to explain the nature of contemporary conflict,10 today variety is often acknowledged as being its defining characteristic. To an extent elements of each theory therefore remain valid. This situation is summarised by Michael Evans, who asserts that, following the end of the Cold War:

War became at once modern (reflecting conventional warfare between states), postmodern (reflecting the West’s cosmopolitan political values of limited war, peace enforcement, and humanitarian military intervention), and premodern (reflecting a mix of substate and transstate warfare based on the age-old politics of identity, extremism, and particularism).11

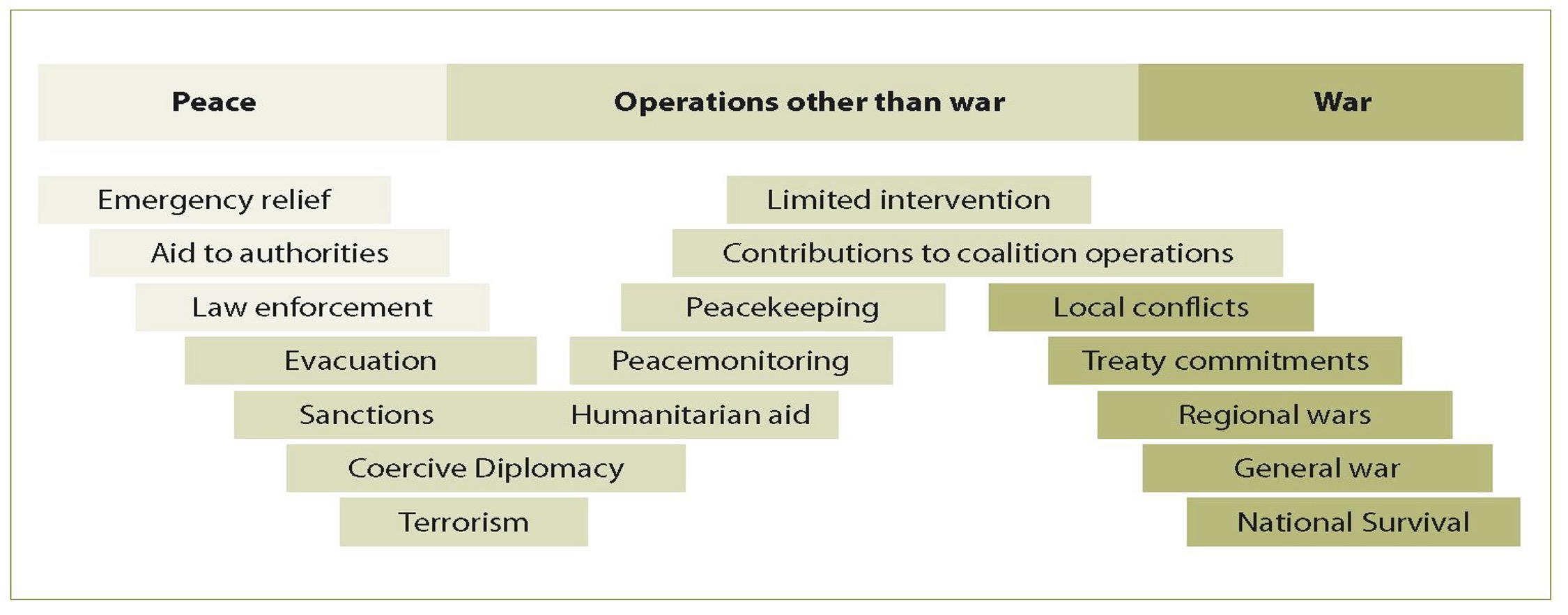

In essence, this divergence means that modern militaries, including the Australian Army, must now prepare for conflict across the entire spectrum of operations (see Figure Two), rather than only at its ‘top end’, as was traditionally the case.

This change in the scope of conflict has been accompanied by several new technologies and environmental and societal trends, all of which have led to changes in the nature of the tasks and challenges facing the contemporary junior commander. First, the dissemination of night vision equipment means that night operations can now be conducted more easily, leading to the concept of ‘the continuous battle’ in which forces may be required to conduct operations around the clock, potentially for several days.12 Second, shifting demographics mean that contemporary operations are more likely to occur in an urban environment (in the 100 years to 1990, the percentage of the world’s population living in cities increased from 14 to 43, a growth trend that continues to the present day).13 Third, strict rules of engagement (particularly during peacekeeping operations) can severely constrain the use of force, meaning that a junior commander may not necessarily have access to the full range of options previously available to facilitate the completion of this type of mission.14 This is, to an extent, linked to the fourth shift in the nature of conflict—the increased role of the media in determining the course of conflicts.15 For the junior commander, this shift has resulted in a greater need to ensure that all personnel under one’s command are aware of the impact their actions may have on the broader development of a conflict.16 Fifth, the traditional notion of a ‘linear battlefield’ has been largely replaced by the concept of a four-dimensional ‘battlespace’, one in which it is difficult to determine the enemy’s fronts and flanks.17 Increasingly, this shift is resulting in the need to take a combined-arms, joint force or interagency approach in order to successfully engage enemy forces.

Indeed, one of the most significant changes of the past twenty years has been adapting to enemy forces that are vastly different in nature to traditional (i.e. conventional) forces. Whereas the Soviet military was characterised by a strong emphasis on centralised control, had a well-developed military doctrine that was closely followed at all levels and a conventional strategy that relied heavily on weight of numbers,18 the enemies confronting Australia’s forces today rarely have any of these features. Instead, the adversarial forces faced today are frequently ‘amorphous, locally and regionally based groups and networks lacking a unifying ideology, central leadership, or a clear hierarchical organization’.19 Furthermore, these forces frequently exploit their superior local knowledge in order to hide amongst the local population, making them difficult to identify (a factor that both enables and exploits the ‘battlespace’ concept discussed above). Armed with this advantage, the enemy is also usually harder to engage prior to an attack being launched against friendly forces and harder to find once they disengage

Figure Two. ‘The Spectrum of Operations’.

Source: Commonwealth of Australia, ADDP-D.3: Future Warfighting Concept, Department of Defence, Policy Guidance and Analysis Division, Canberra, December 2002, p. 24.

Effectively Prepared Staff Cadets?

Overall, this plethora of new developments means that contemporary commanders face a far more complex and fluid environment than that of twenty years ago, which leads me back to the intent of this paper—does the current PT GSO FAC effectively prepare a Staff Cadet to be a platoon commander in this environment? Contrasting my experience of the course with the character of modern conflict described above, my answer is that although the PT GSO FAC does prepare Staff Cadets for the challenges they are likely to face as junior commanders, there are a few key areas in which the course could prepare them better. Due to space constraints, the following discussion does not address the many positive aspects of the course in great detail. Rather, it is limited to an examination of six key areas: four where training should be improved and two where positive aspects of the course could be better capitalised upon. Some suggestions of possible ways to make improvements are also made with regards to each area.

Yesterday's Enemy

I will begin with the most immediately apparent shortfall in the current PT GSO FAC: the lack of training against forces that are similar in structure and modus operandi to those likely to be encountered by Australian forces on operations. At present, Staff Cadets spend the majority of the course training to fight an enemy that uses Soviet doctrine, albeit that this is thinly disguised behind a Musorian veil. In order to better prepare junior commanders to fight contemporary enemy forces, the simulated enemy that Staff Cadets train against should be updated to take into account current operational experiences. For example, a training scenario could include an intelligence brief stating that the enemy has been using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) along certain routes through the area of operations. This would encourage Staff Cadets to consider which routes are the safest to use from a different perspective (e.g. ‘am I likely to take casualties from IEDs if I use this route to the form-up-point?’).

This example is, of course, overly simplistic. In reality, the inclusion of such details would have to be carefully managed in order avoid causing confusion during the early stages of training. Providing this was to occur however, training against a simulated enemy that more closely mirrors those encountered on current operations would be greatly beneficial. Whilst I will refrain from making suggestions about the exact form such an enemy should take, it is important to note that the objective of any alteration to the enemy simulated in training scenarios should be the encouragement of greater levels of lateral thinking about the situation and possible actions of the enemy forces.

Yesterday's Scenarios

As the scenario presented at the start of this paper suggests, tactics and doctrine are currently taught in relation to the ‘defence of Australia’ scenario, which is anachronistic in light of Australia’s contemporary security challenges and the current focus on expeditionary operations. A more realistic training program would involve scenarios wherein Australian forces were deployed overseas in aid of an allied government (rather than only involving scenarios wherein Australia is being invaded). Furthermore, training scenarios should be updated to take into account modern battlefield conditions, for example by including areas heavily populated by civilians. Such an inclusion would serve not only to increase the realism of training scenarios, but would also reinforce other aspects of the training program, such as the laws of armed conflict (LOAC) component, by forcing Staff Cadets to take it into account when conducting the IMAP.20

This problem is not, however, limited to the tactical and doctrinal components of the course. The historical components of the course syllabus, although engaging learning aids, are frequently of only partial relevance to contemporary junior commanders. This is because, although they provide good examples of sound planning, mission execution and the application of the ‘principles of leadership’, they do not necessarily demonstrate to Staff Cadets how to successfully transplant their application into the modern context. This situation could be easily remedied by expanding the scope of pre-course training components, which currently include a case study of the Battle of Maryang San (2-8 October 1951) and the lessons to be drawn from it. The inclusion of a second, more recent case study, such as the Second Battle of Fallujah (November 2004)21 would promote a greater understanding of the nature of current ‘high intensity’ battles.22 It would also allow Staff Cadets to learn about the challenges facing the contemporary junior commander by way of historical contrast, in addition to reinforcing the notion that the ‘principles of leadership’ are a timeless phenomenon. Any subsequent discussion that contrasts the two battles would have a positive reinforcing effect.

Too Narrow A Spectrum

Given the variety of operations in which the Australian Army is currently engaged, the scope of the PT GSO FAC should be broadened to take into account both more complex environments and the array of military endeavours that occur at all levels of the spectrum of operations (see Figure Two). Currently, the PT GSO FAC focuses only on operations that occur at the ‘top end’ of the spectrum (i.e. large-scale conventional warfighting), in a battlespace where the enemy is clearly defined and the rules of engagement are simplistic. Instead, training should be broadened to take into account the variety of environments in which junior commanders may now find themselves. This could be done by increasing the focus given to preparing for operations further down the spectrum.

Prior to offering some suggestions as to how this may occur, it should be mentioned that on the few occasions that I have raised this issue with my peers and instructors alike, the reply is generally that training focuses on conflict at the ‘top end’ of the spectrum of operations because these operations are the most difficult type of conflict. The implication, therefore, is that if Staff Cadets can become proficient at ‘top end’ warfighting, mastering other forms of operations will be easy. My reply to this assertion is twofold. Firstly, even if this claim were accurate, the nature of modern warfare means that contemporary operations at the ‘top end’ of the spectrum of conflict are different in nature to those we are currently training to fight (see above). Secondly, the idea that training focused solely on warfighting at the ‘top end’ of the spectrum of operations will result in the successful conduct of other types of operations is erroneous. As recent operational experience has testified, challenges presented to the junior commander during operations other than high-intensity warfighting can be just as stressful and difficult to overcome. Indeed, the elevation of one group of challenges to a position of pre-eminence within the PT GSO FAC training program may actually reflect the Australian Army’s history and cultural values rather than an evaluation of actual operational experience.23 Nevertheless, there is a solid case for broadening the focus of the PT GSO FAC so that it better prepares Staff Cadets.

This broadening of scope could be achieved quite easily via one (or more) of a number of options. For example, part of the course could focus exclusively on addressing the requirements of a platoon commander that are unique to peace enforcement or low-level counterinsurgency operations. Alternatively, the requirements of the junior commander during different types of operations could be taught using the ‘three block war’ approach currently practiced by the US Marine Corp and Canadian Forces.24 Cadets could, having learned the ‘principles of leadership’, apply them to the situations they could expect to encounter in each. Subsequently, field modules of the course could simulate the environments contained within each of the ‘blocks’ within close temporal proximity, allowing Staff Cadets to both experience the rapid change in environments they are likely to encounter on operations and apply their training within each environment. This approach would have the added bonus of providing both relevant and stimulating training without greatly increasing the length of the course.

Yesterday's Ground

I was the only Staff Cadet in my unit whom had seen an urban operations training facility. Given the trend towards operations occurring in the urban environment, this situation constitutes a deficiency in the current training program. Furthermore, I suspect that this is not a problem limited to the PT GSO FAC, but rather is a widespread deficiency in Army Reserve training. The good news with regard to this shortfall is that the situation may soon be remedied as recognition of the need for greater levels of urban training for Regular Army personnel has recently led to the construction of several urban operations training facilities around the country.25 Over the next few years this will no doubt result in a ‘flow-on’ effect to Reserve training. In the interim, this training shortfall could be partially addressed by the inclusion of some ‘basic’ urban tactics theory lessons in one or more of the PT GSO FAC’s continuous training modules. Although far from an ideal solution, such an inclusion would be an improvement over the current situation.

Getting Better Mileage

The contribution of training staff at all stages of the PT GSO FAC has been, in my experience, outstanding. One of the major benefits of the course is the combined wisdom and consistently high levels of enthusiasm brought to it by training staff from a variety of backgrounds within both the Australian Regular Army and Reserves. That said, training staff remain an under-utilised asset in a few key ways; the training program could benefit further from their experience, particularly those that have served on recent operations as junior commanders. This is a situation that can be remedied simply. First, encouraging training staff to give presentations to Staff Cadets about their personal experiences is a great way to allow them to directly pass on the lessons learned from those experiences.26 It also has the added benefit of engaging Staff Cadets by presenting them with situations with which they can readily empathise. Second, given the increasing incidence of combined-arms and joint approaches, the corps-specific background of non-Infantry Corps staff could be more heavily drawn upon throughout the course. A greater understanding by Staff Cadets of the roles of the various corps would ultimately result in a greater incorporation of combined-arms approaches into their TEWT solutions, in a learning environment where solutions can be critiqued by staff from a variety of backgrounds and with a variety of experiences.

One of the benefits of a training program that draws heavily on LWD-1 is that the models contained within LWD-1 are flexible enough to be relevant to most situations. The same could be said of the IMAP. In short, what can be summarised as the ‘how to think, not what to think’ philosophy remains a valid paradigm in the contemporary environment. This element of the course should therefore be retained; however, the way in which it is taught will need to be altered if the shortfalls identified above are to be addressed. For example, a discussion of the additional situational factors that need to be taken into consideration during typical missions encountered by junior commanders on peacekeeping operations or during urban operations would allow Staff Cadets to practice applying the ‘how to think, not what to think’ approach to environments that are not at the ‘top end’ of the spectrum of conflict, against an enemy that does not adhere strictly to doctrine. This broadening of the scope of the training program would ultimately provide great benefit because it would teach Staff Cadets to more effectively apply the ‘how to think, not what to think’ approach in a broader variety of situations.

Final Thoughts

In November 2002, a company strength Army Reserve contingent deployed to East Timor as a part of 5/7 RAR—the first overseas operational deployment undertaken by a sizeable contingent of Australian Army Reserves since the end of the Second World War.27 More recently Army Reserves have also been deployed on operations in Sumatra (in the wake of the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004) and to Solomon Islands. Thus it is increasingly essential for Army Reserve training courses, including the PT GSO FAC, to reflect operational realities. At risk of sounding cliched, it is of increasing importance that the Army Reserve trains as it intends to fight, for ultimately Reserves will fight as they have been trained.

It should be noted, however, that despite the need for improvements in specific areas, the remainder of the course is generally highly relevant to the contemporary situation, especially with regard to the teaching of individual soldierly skills. To this end, two of the positive aspects of the course were also highlighted above and some ideas regarding how to better utilise them were postulated. Returning to the question posed at the start of this paper—does the PT GSO FAC effectively prepare a Staff Cadet to be a platoon commander in the contemporary operational environment—my answer is that, while the course is effective overall, it could nonetheless be improved in several ways. Ultimately these improvements would make the course even more valuable, maximising the chances that Staff Cadets will become effective junior commanders in the modern operational environment.

Endnotes

1 Musoria is a fictional country located somewhere to Australia’s north. It is used by the Army as a training aid when a simulated enemy force is required. Although there is not much interest in Musoria outside of the military, a quick Internet search nonetheless led me to a website that revealed that ‘Musoria represented a much larger country that supposively [sic] had the ability to carry out a fully-fledged invasion of the Australian landmass, adopting Soviet military doctrine and order of battle’. See: <http://everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=1531004>, accessed 14 November 2006.

2 By ‘nearing the end of the Army Reserve Officer training program’ I am referring to a Staff Cadet who has completed Third and most if not all of Second Class, and is preparing to attend RMC for the final modules of the PT GSO FAC.

3 For more information on the PT GSO FAC syllabus see: The Royal Military College of Australia: Handbook, Duntroon: RMC-A, 2005, pp. 21-2.

4 See: Australian Army, LWD-1: The Fundamentals of Land Warfare, Land Warfare and Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2002.

5 Australian Army, LWD 0.0: Command, Leadership and Management, Land Warfare and Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2003, pp. 3.20-3.23.

6 Paul Dibb, Review of Australia’s Defence Capabilities: Report for the Minister of Defence, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1986, p. 1.

7 Ibid.

8 Commonwealth of Australia, The Australian Army in Profile 2005, Army Headquarters, Canberra, 2005, pp. 4-63.

9 The Right Hon. John Howard, Address to the ASPI Global Forces 2006 Conference - Australia’s Security Agenda, Hyatt Hotel, Canberra, 26 September 2006 [Transcript available online, accessed 14 November 2006: http://www.pm.gov.au/news/speeches/speech2150.html]

10 For example, see: Martin van Creveld, The Transformation of War, The Free Press, New York, 1991; Alvin Toffler & Heidi Toffler, War and Anti-War: Survival at the Dawn of the 21st Century, Little, Brown and Co., Boston, 1993; United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Vision 2020, US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, June 2000; Thomas X. Hammes, The Sling and the Stone: On War in the 21st Century, Zenith Press, St Paul, MN, 2004; Barry R. Posen, ‘Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of US Hegemony’, International Security, Vol. 28, No. 1, Summer 2003, pp. 5-46; John Garnett, ‘The Causes of War and the Conditions of Peace’ in John Baylis, James Wirtz, Eliot Cohen & Colin Grey (eds), Strategy in the Contemporary World: An Introduction to Strategic Studies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002, pp. 66-87; Jeremy Black, ‘War and Strategy in the 21st Century’, Orbis, Vol. 46, No. 1, Winter 2002, pp. 137-44.

11 Michael Evans, ‘From Kadesh to Kandahar: Military Theory and the Future of War’, Naval War College Review, Vol. 56, No. 3, Summer 2003, p. 135.

12 Australian Army, LWD-1, p. 24.

13 L. B. Sherrard, ‘From the Directorate of Army Doctrine: The Future Battlegroup in Operations’, The Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin (Canada), Vol. 6, No. 3, Fall/ Winter 2003, p. 6 (esp. figure 1-1).

14 See Leslie C. Green, The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict, 2nd ed, Juris Publishing Inc, New York, 2000.

15 Margaret H. Belknap, ‘The CNN Factor: Strategic Enabler or Operational Risk?’, Parameters, Vol. XXXII, No. 3, Autumn 2002, pp. 100-114.

16 Peter Leahy, ‘Welcome to the Strategic Private,’ Defence Magazine, October 2004 [Available Online, accessed 14 November 2006: http://www.defence.gov.au/defencemagazine/editions/011004/groups/army.h…].

17 Australian Army, LWD-1, pp. 42-4.

18 John Erickson, Lynn Hansen & William Schneider, Soviet Ground Forces: An Operational Assessment, Westview Press, Boulder, 1986, pp. 51-140.

19 Michael Eisenstadt & Jeffrey White, ‘Assessing Iraq’s Sunni Arab Insurgency’, Military Review, Vol. 86, No. 3, May-June 2006, p. 33.

20 For example, the presence of civilians in the Area of Operations may preclude the use of artillery support to a platoon attack, even if such assets are offered as part of the scenario. Identifying that the use of such an asset would violate LOAC (and hence be against the rules of engagement) would become a vital part of the IMAP in such a scenario.

21 This Battle would provide a good point of contrast as it, like Maryang San, lasted several days and involved detailed planning on the part of Coalition forces. Unlike Maryang San, the conduct of the Second Battle of Fallujah was affected by several of the aspects of contemporary warfare discussed above. For further details of the Second Battle of Fallujah, see: Thomas E. Ricks, Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq, Allen Lane, London, 2006, pp. 398-406.

22 I do not advocate replacing the case study of Maryang San completely because there are some key differences between it and the proposed case study of the Second Battle of Fallujah. Importantly, for example, Maryang San was fought by Australian forces, meaning its continued use as a case study has the additional benefit of teaching Staff Cadets about Australian Army history and traditions. The Battle of Maryang San: 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment, Korea, 2-8 October 1951, Headquarters Training Command, Canberra, 1991.

23 This is not a phenomenon limited to the Australian Army alone; rather, it has been asserted that the pre-eminence of ‘top end of spectrum’ conflict is a longstanding feature of ‘Western’ culture. See: Jeremy Black, Rethinking Military History, Routledge, London, 2004, esp. pp. 55-8.

24 A Soldier’s Guide to Army Transformation: Three Block War, Canadian Forces, 2006 [Available online, accessed 14 November 2006: http://www.army.gc.ca/lf/English/5_4_1_1.asp].

25 At the time of writing, the most recently constructed ‘temporary’ urban operations training facility is located at the School of Infantry at Singleton. Chris Bennett, ‘Temporary UOTF’, Australian Infantry Magazine, October 2006-April 2007, pp. 80-1.

26 It should be noted that I have experienced this first hand from time to time, although not as a formal component of the course, and it is this experience that has convinced me of the benefit of presentations of personal experience as a training mechanism.

27 Damien Kook, ‘Operation Citadel: First Reserve Deployment Overseas Since WWII’, Australian Infantry Magazine, October 2002, p. 33.