The Burden of Bonuses

Abstract

This article examines the use and effectiveness of retention bonuses in the Australian Army. These bonuses have been implemented at considerable expense despite the absence of a solid basis of empirical research regarding either their effectiveness or the potentially unintended consequences that can arise from their payment. The author examines each of these issues in turn and concludes that retention bonuses, despite their questionable logic and rationale, are still useful as a temporary measure to ‘buy time’ for the longer-term root causes of separation to be addressed.

Introduction

The payment of a retention bonus is often seen as a panacea to manning deficiencies in Army. Whether these deficiencies are caused by separation rates, low recruitment, poor force structure, or some other external factor, the view exists that applying a bonus will overcome some or all of the problems that have caused the deficiency to develop. Unlike other retention initiatives, bonuses are also thought to have an almost instantaneous effect, the results of which can be seen shortly after implementation.

Unfortunately, there is little documented evidence to show that a bonus has any long-term effect beyond the payment period of the bonus. More dramatically, there is no empirical evidence that bonuses in Army (or indeed the Australian Defence Force) work at all. This is not to say they do not work; it is just an observation that there has been no statistical validation of past bonus initiatives to examine whether there has been an increase in retention that can be attributed to the bonus.1

Even with no evidence that the payment of a bonus will achieve its intended outcome, the continued application of bonuses suggest that there is little doubt with policy developers that they increase retention—to suggest otherwise would seem counter-intuitive. Therefore, bonuses are applied even without empirical evidence of their effectiveness under the broad assumption that retention is directly linked to remuneration, and the higher the remuneration the higher the retention.2 However, there are costs and risks in applying a bonus which are not immediately evident and which may not surface until well after the bonus has come and gone.

This article will examine the potential second-order effects arising from the application of retention bonuses from a policy and force structure perspective. In order to place this article in context, the conventional rationale behind a bonus is discussed briefly, prior to detailing some of the possible second-order effects. Finally, considerations for implementing a bonus are outlined in order to provide some insight into why bonus initiatives to decrease separation are not as straightforward as a problem versus solution dichotomy in the usual systems analysis construct.

Selected Literature Review

Nunn Review

The Review of Australian Defence Force Remuneration 20013 provided many recommendations, some of which were in the area of bonuses. Significantly, in discussion of the relevance of bonuses the review found that there has been ‘payment of bonuses, and in some cases multiple bonuses, to individuals who either had no intention of leaving the ADF, or who did not possess the skill sets being sought by the external market’. The review indicated that payment of bonuses can be inefficient and may not achieve the intended effect of improving retention.4

Nunn also stated that bonuses should ‘be devices of last resort used to counter unexpected external targeting of high value employees’ and when they are used ‘they should be specifically targeted and monitored for performance’.5 The review also discounts the concepts of remuneration equity and instead proposes that financial incentives could be offered on an individual basis rather than across cohorts.

Australian National Audit Office

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has presented two reports on the retention of military personnel: the first in 2001, followed by a follow-up audit in 2003. The initial report indicated that ‘Expenditure on retention has the potential to be much more cost-effective than expenditure on recruitment and training’.6 However, the research also indicated a perception that some retention and completion schemes (including bonuses) ‘did not necessarily have a great impact upon retention rates ... because they did not address the reasons personnel were separating, but merely raised the price of someone who was in the market for other reasons’.7

The ANAO research provided some qualitative evidence that bonus schemes may not be cost effective because they were paid to personnel who were not intending to separate, and were often applied after a problem had become apparent.8 ‘The ANAO also found that Defence has not conducted an overall assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of retention schemes for use in the development of subsequent retention schemes.’9 It outlined that Defence needed to develop a much better knowledge of the incentives that work and the reasons for their success.10 The report concluded its discussion on retention by stating ‘There is no clear evidence that specific retention schemes are cost effective’ and that Defence should collect evidence on the effectiveness of these schemes.11

The follow-up ANAO audit leveraged heavily from the findings of the Nunn review. In its discussion on the costs of recruiting and training compared with retaining already trained personnel, the report surmises that ‘substantial investment in retaining these personnel could be cost-effective’.12 However, the difficulties in attributing the cost of recruiting and training in order to inform an assessment of how much should be expended to retain an individual, combined with the intangible cost of experience, was acknowledged. 13

The literature from Nunn and ANAO highlighted three key points:

- Army does not know whether retention bonuses are effective in increasing retention;

- Army does not know whether retention bonuses represent a cost effective method in retaining personnel; and

- underpinning the previous two points, no measurement of the effectiveness of bonuses has been undertaken to inform decisions on the viability of these schemes to reduce retention, or achieve the desired outcome.

The Rationale and Theory of a Bonus

The commonly accepted first-order effect of a retention bonus is that it will reduce the likelihood that individuals in a particular target group—whether it be rank, trade or experience level—will choose to resign. This will obviously reduce the separation rate and result in higher cohort numbers of the target group in current and later years, thereby enhancing or maintaining defence capability and enabling enough time to correct the deficiency in force structure.

The base assumption, therefore, is that members who would otherwise have resigned had a bonus not been offered will change (or at least defer) their decision by accepting the bonus and a subsequent undertaking for further service (UFS). Simplistically, by offering a bonus, individuals are compelled to compare how much worse off they would be if they resigned and entered non-military employment compared with accepting a bonus and remaining in Army.14 If that difference is significant and can be rationalised within their own personal circumstances then an individual will choose to stay. In micro-economic terms, a bonus effectively places a cost on other reasons for leaving and elevates remuneration to a higher consideration for separation than would otherwise have been the case (and may also eliminate low remuneration as a potential reason for leaving).15

The amount of bonus required for an individual to be retained may vary. Some personnel may require a very large bonus so that other considerations for separation—such as family reasons, posting stability and career progression—are no longer significant when compared with the benefits a bonus can provide. Other personnel may require almost no bonus at all, indicating they are satisfied with their own personal circumstance and level of remuneration. A challenge, therefore, is to identify how much bonus needs to be paid to negate other reasons for separation for most of the target personnel.16

Unfortunately there is no formula for determining the monetary amount of a bonus. The amounts of recent bonuses seem to be arbitrary and based on a combination of subjective assessments and the funding available in the retention budget rather than how much is actually required. To achieve the specified intent, bonus amounts cannot be set so low as to not achieve any increase in retention, but can also not be set so high that they present an unreasonable financial liability to Army. The irreversible nature of the introduction of bonus schemes also represents a risk in setting the correct amount as Army cannot easily increase or decrease the amount of bonus post-implementation.17

Of course an individual can choose to both not accept the bonus and stay in Army, having made the conscious decision that flexibility to leave at a time of their choosing was ‘worth more’ than the bonus provided. To them, the bonus actually represents a ‘cost of staying’ if they make it to the same length of service as their cohort counterparts who accepted the bonus. In other words, it is money they have missed out on because they finished up serving just as long as personnel who accepted the bonus. This notion may of itself induce the separation of individuals who may consider that their remuneration is not equitable, even though they are primarily responsible for the decision that resulted in the inequity.18

False and Misleading Assumptions in the Need for a Bonus

One criticism of the rationale behind applying a bonus is a seemingly automatic assumption that retention is the root problem in a trade which suffers from a high proportion of vacancies. A high number of vacancies in a particular trade does not necessarily mean that separation rates are high; in fact, high vacancies are more likely to be a symptom of a poor structure. Although it is true that some trades and ranks suffer from high separation rates at particular points, those most frequently listed on the critical trades and ranks lists also suffer from a poor force structure where the career progression systems are not sufficient to provide the necessary numbers at the appropriate ranks and cohorts.19

A second misleading assumption is that separation is a bad or undesirable characteristic. Separation is actually a necessity in order to allow promotion of personnel and the discharge of personnel no longer suited to the military. Reducing separation rates too far will slow the promotion rates, with the potential side effects of increasing average age, increasing time-in-rank, and potentially inducing separations due to a lack of promotion opportunity in the long term. Defining ‘good’ separation and ‘bad’ separation rate can be broadly determined using workforce modelling and is likely to vary between trades.

A further misleading assumption is that separation rates within Army are high in general. Although Army strives to reduce separation rates when compared with other similar armies, the national labour market and similar occupations, the separation rates within Army are comparable.20 Importantly, worker mobility in the Australian labour market peaks between the ages of 20 and 34, which also represents the key demographic for experience and rank within Army.21 Therefore, although Army experiences relatively high separation between the ages of 20 and 34, this could be reasonably expected given the mobility of the key demographic in the remainder of the labour market.22 The ability of Army to significantly influence this demographic characteristic is unknown, however, would most likely require significant resources to achieve.

Even an assumption that present levels of remuneration are not high enough to retain the right personnel might not be valid. Recent exit surveys and Defence Attitude Surveys have not placed remuneration as a top ten reason for leaving.23 It seems incongruent then, that Army would consider a bonus knowing that there are other significant areas affecting retention which might be more specifically addressed. The answer may be that it is easier to design and implement a bonus scheme to target a specific critical group compared with the cost associated with addressing some of the other reasons cited for leaving.

The need for a bonus should therefore not be based purely on high vacancies, high separation, or a perception of needing to improve remuneration. Instead they should be structured around enabling sufficient time in which the structural inadequacies of the trade can be addressed and corrected. Retaining personnel of a particular rank and trade, although useful, is only a short-term solution. If utilising the time bought (by paying the bonus) to recruit and train personnel at subordinate ranks such that they can be promoted into the inevitable vacancies is wasted, then the bonus has only been effective in maintaining the capability for a very short period and has not fixed the inherent problems within the trade.

Measuring the Success of a Bonus

Conventional wisdom suggests the measurement of an intended outcome should be a routine aspect of the introduction of a bonus initiative. Measurement represents a part of the feedback loop and allows assessment of the scheme in order to inform future initiatives.24 However, as highlighted earlier, Army has not conducted any statistically robust analysis of the short or long term success of bonus schemes.

In measuring the success or otherwise of a bonus, it is important to appreciate that retention figures can be extremely sensitive to variation. An entire cohort of captains, for example, comprises about 270 officers and any policy which alters the decisions of just a handful of captains represents an effect of several percentage points.25 Therefore policy-makers need to be aware that any negative second-order effect resulting from introducing a bonus which induces resignation of just two or three officers effectively reduces the effectiveness of a bonus. A culmination of these effects could completely reverse the intended effect of a bonus and may even result in a worsening situation in the mid-long term.

Overall, measures of the success of a bonus should examine both the immediate effectiveness and the long-term benefits to force structure and capability. This suggests continual analysis in not only the short term, but also well into the future and the ‘life’ of the cohort. Confounding events such as the simultaneous introduction of policies, retention initiatives and increases in wages could make the attribution of reduced separation to the bonus scheme non-trivial and requiring analytical support to interpret.26 Such support also requires a large amount of data to facilitate the comparison of what might have been expected to occur should a bonus not have been applied.

The Burden of Bonuses

As with many policies, particularly in the field of personnel policy, there can be numerous second-order effects, some of which enhance the intended effect of the policy and others that may compromise the intended outcome. With the implementation of bonus schemes, most of the second-order effects relate to cost, force structure and career impacts. The collection of these effects represents the burden, positive or negative, of bonus scheme implementation.

Premium on a Bonus (Economic Rent)

To be effective, a bonus must be appealing to personnel who were otherwise going to resign. Payment of a bonus to personnel who would otherwise have stayed is effectively the premium paid to retain the few who would not have stayed.27 For example, if a cohort consists of one hundred personnel, and it is anticipated that ten per cent (ten personnel) will resign during the year, then to attempt to retain those ten personnel the bonus will need to be offered to the entire cohort. In other words, the bonus will also need to be offered to the ninety personnel who were going to stay anyway, and not just the ten target personnel. Hence the premium is likely to be a significant amount.28

This premium, even if it is a large amount, may well be cost effective. Attributable costs of recruiting, training, and ensuring a force structure is in place to sustain experience at the right level could exceed the costs of applying a bonus and would therefore represent value for money.29 However, if the bonus is not well accepted, then its payment may be nothing more than extra money in the pockets of people who were prepared to stay in any case and thus may not have captured the target audience at all. The chance of this occurring represents the fiscal risk of committing funds before the results are known. Simplistically, therefore, the take-up rate must exceed the normal retention rate over the life of the bonus, and the cost of the bonus must be less than the cost of recruiting and training the additional personnel in order to be considered a short-term success.

Career Decision Points

There is tacit acknowledgment that personnel make their retention decisions during certain discrete periods of time. In general, personnel do not continually scan employment pages or submit resumes to external organisations (public or private). However, during certain periods individuals may have a greater propensity to consider employment options outside the military. These periods are generally referred to as career decision points (CDP) and are historically represented through an increased propensity to leave at certain points in their career.30

Career decision points often coincide with certain events throughout the career of personnel. They may be associated with courses, promotions, postings, lapse of a return of service obligation (ROSO), notification of competitiveness, or a personal situation, and typically involve a comparison of where an individual may view themself in a future military appointment with where the career management agency may see that individual. The greater the discrepancy between the individuals’ thoughts on postings, promotions, lifestyle, and career progression from that of the career management agency, the greater the propensity to leave is likely to be.

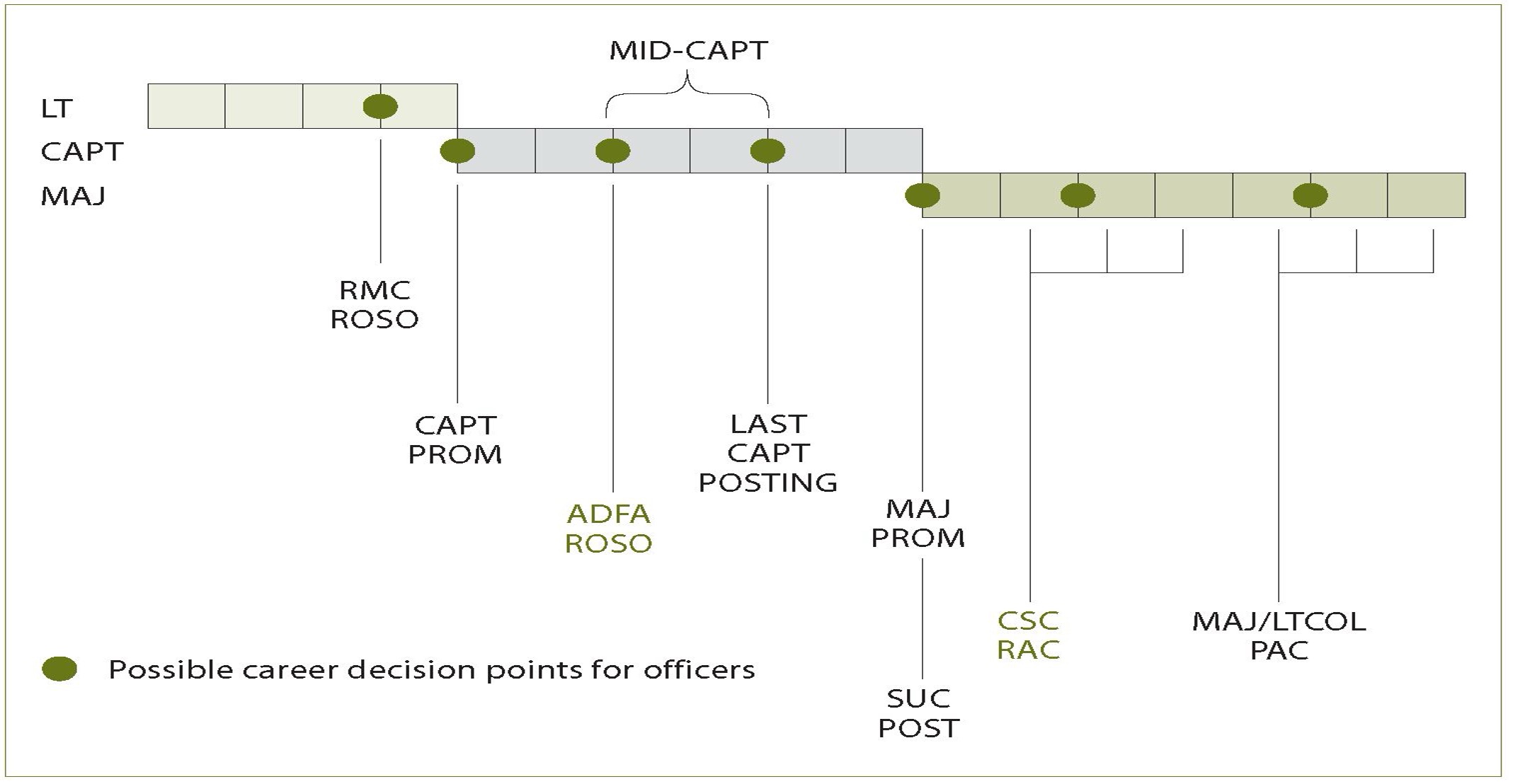

Figure 1 shows an example of the possible CDPs for a General Service Officer (GSO) who has graduated from the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA). Other ranks and types of officers have similar CDPs throughout their career. Every time a career decision point is encountered, an individual will assess their future in the military and make a decision to stay or leave, with the latter decision contributing to separation rates. The deliberate application of a well timed bonus can potentially contribute to a decrease in the number of CDPs, which would result in fewer periods where a member considers discharge, thereby marginally improving retention. Conversely, a poorly timed bonus scheme may introducean additional CDP.

As shown in Figure 1, there is likely to be up to four CDPs between the lapse of ADFA ROSO and the Promotions Advisory Committee (PAC) decision on selection for Command and Staff College (CSC). The introduction of a bonus just prior to the lapse of ROSO, which has a UFS likely to take them up to CSC PAC, could reduce the CDPs from four to just one. However, in designing the bonus, the timing of the lapse of the UFS should be planned such that it does not introduce its own career decision point (in addition to those already in existence). If the end of the UFS can be timed to occur at an existing career decision point—such as promotion, selection for CSC, a subject course or a posting—then the individual is still only confronted with one career decision point, even though the magnitude of the decision may have increased. Unfortunately, current bonus schemes appear not to have considered CDPs and in some instances may have inadvertently introduced an additional decision point.

Figure 1. Possible career decision points for GSO ADFA graduates.

Delaying the Inevitable?

Bonuses, in effect, buy personnel for a period of time. Once that time elapses, the characteristics defining the structure of the trade may simply return to pre-bonus conditions provided there have been no further bonus schemes or other confounding retention initiatives. Unfortunately, as detailed earlier, there is little empirical evidence by which to examine whether structures have indeed returned to their pre-bonus status or not.

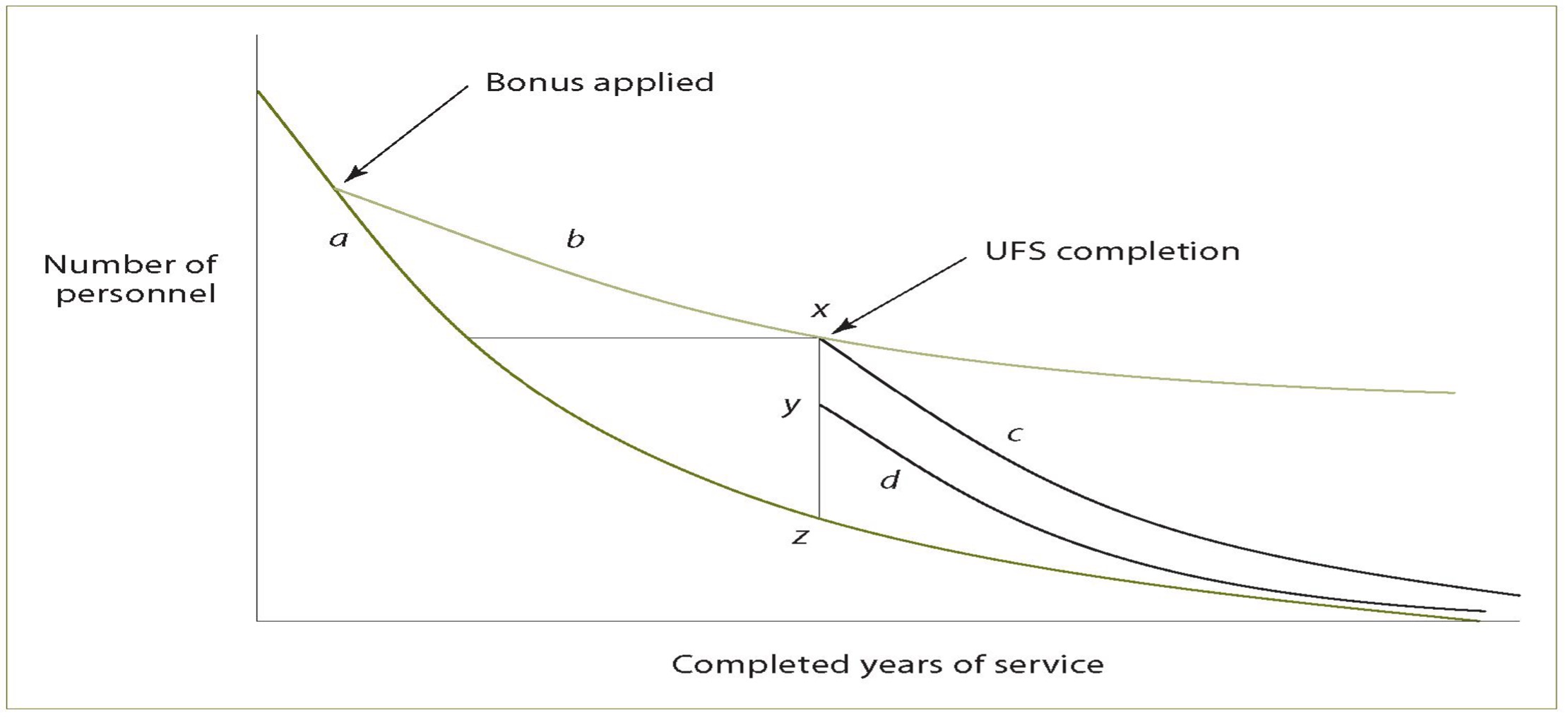

It is therefore unclear whether the structure of a trade completely returns to normal or whether there is some post-bonus residual benefit. Figure 2 shows an indicative normal year-of-service profile in line a and the intended post-bonus profile in line b. At the completion of the UFS/ROSO period at point x it is unknown whether the profile continues to follow b, follows a new profile in line c, whether numbers drop to point y and then follow line d, completely return to point z, or assumes some other profile. It is also unclear whether the residual effect, whatever it is, is beneficial to force structure or whether the increased retention will create a flow-on of effects including blocking the promotion of more junior cohorts.

Still, it is reasonable to suggest that at the completion of the UFS, there will be an increase in separation in the target cohort as the figures undergo a form of correction. Without analysis and understanding that this is a side effect of applying a bonus in the first place, personnel planners might perceive the sudden increased separation as a worsening situation and it may induce them to recommend a subsequent retention bonus which would lead to a risk of applying continually rolling bonuses.

Provided Army personnel planners are conscious that a purpose of the bonus is to use the ‘bought time’ to correct any systemic structural problems within the trade, and not to use the bonus in its own right to correct the problem, then when the post-bonus correction in separation rate occurs, Army will hopefully have fixed those systemic force structure problems. Should Army fail to correct the force structure during this grace period then the bonus will only have been successful in the short term, the trade will continue to experience force structure problems (perhaps even exacerbated by the bonus), and there will be pressure for a rolling requirement for more bonuses.

Figure 2. Example profile of the number of personnel by completed years of service.

Force Structure

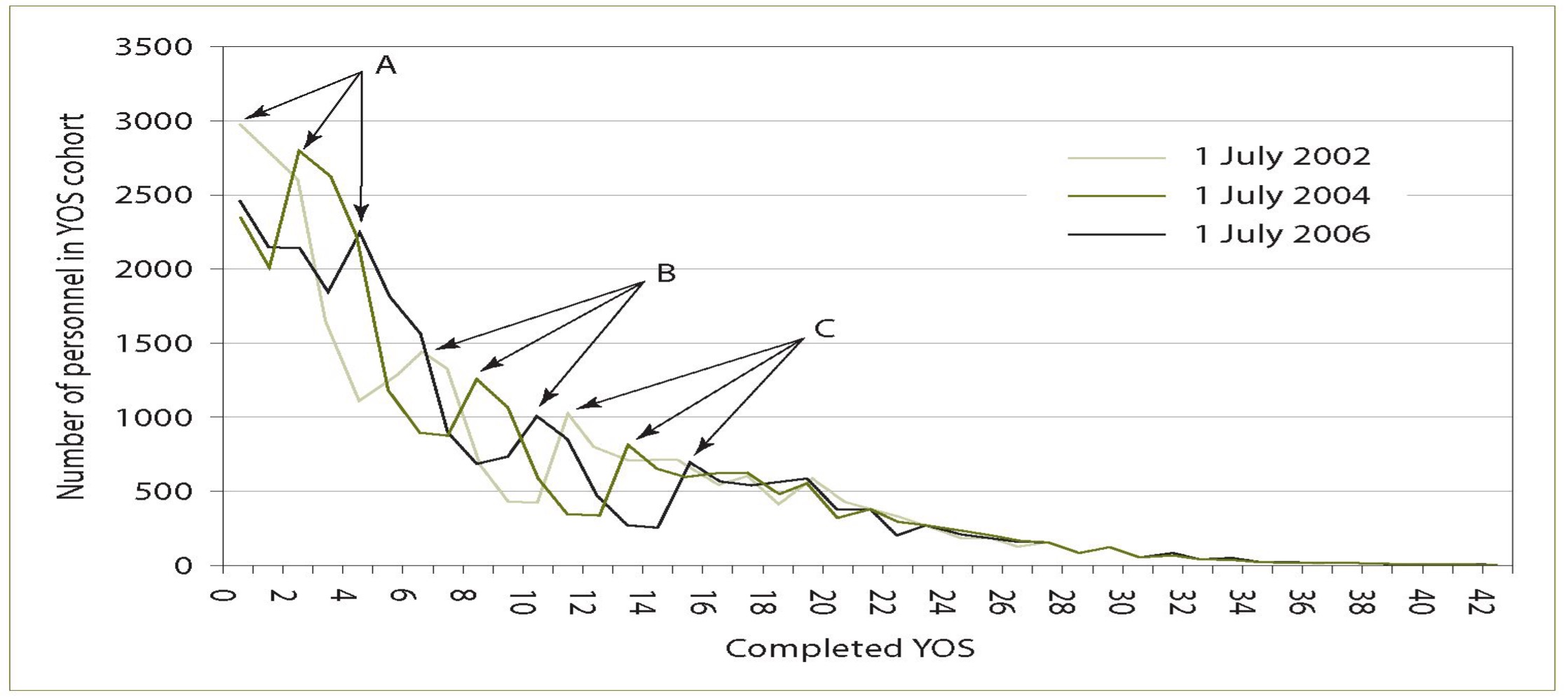

Notwithstanding the possibility of a bonus simply delaying the inevitable, there are also several other force structure implications in introducing a bonus. Notably, within a particular cohort or trade, a bonus could create larger numbers in the targeted cohort compared to other more senior or junior cohorts. As this cohort passes through its career it distorts the normal profile (years of service profile) of a trade and can appear as a cohort bubble which has ramifications for both career management and force structure.

Figure 3 shows where several of these bubbles already exist in the completed years of service profile in the ARA.31 Each profile line shows the number of people in the ARA by the completed number of years they have served. There are three profile lines, one each for 2002, 2004 and 2006. These profiles clearly show at least three bubbles at A, B and C which can be tracked two years apart. Unfortunately, the number of bubbles makes it difficult to determine what the normal profile should look like (although the Directorate of Workforce Modelling, Forecasting and Analysis (Army) DWMFA-A has calculated the ideal profile).

Figure 3. Profile of ARA personnel by completed years of service in 2002, 2004 and 2006.

While a bubble may not appear to be a problem at the aggregated level, as it passes through ranks and career decision points it creates surges and periods of variation in many personnel statistics. Where this variation occurs, planners and policy-makers should identify and acknowledge that fluctuations in separation rates and vacancies could simply be a result of the bonus implementation and not a crisis in retention. It is therefore important that active steps are taken not to make counterproductive policies resulting from nervousness created by any false statistics. Regardless, a bubble will always cause fluctuations in each rank simply as a consequence of large numbers entering and leaving each rank at the time when that cohort becomes eligible for promotion.

Comparatively larger cohort sizes, aside from causing variation, also have several likely effects on the workforce. Assuming that personnel are promoted into a vacancy and not based on time-in-rank, then an increase in a cohort size may increase the number of personnel competing to be promoted. As only a finite number can be promoted, a promotion backlog is likely which then increases the practical time in rank. Similarly, a large cohort at the same rank and experience level will also increase competition for particular postings. Notably, posting related issues are regularly cited in the top ten reasons for discharge and a reduced opportunity for promotion is rated only one less than remuneration as a reason for discharge.32

Any increase in competition for promotion, or desirable postings, has a series of likely unintended consequences. Personnel who were not in the targeted cohort, who now perceive themselves as no longer competitive given the size of the senior cohorts (or not willing to compete even if they are competitive), may initiate discharge earlier than they otherwise would have. Increase in demand for desirable postings may also result in earlier discharge in those who are unable to secure a posting to their preferred locality. The emergence of either of these unintended consequences diminishes the effectiveness of the bonus and may even perpetuate a retention problem in junior cohorts.

Personnel reporting systems also suffer from an increase in cohort size and competition for promotion and postings. Reporting officers not willing to disadvantage their subordinates for promotion may inflate reports which, if conducted across the board, will reduce the discriminating aspects of identifying good performers. Career management agencies would then be forced into utilising non-objective measures of performance, such as career profile, word pictures and personal knowledge, to decide on future postings and promotion.

A larger cohort size resulting from a bonus, as they continue through their UFS, also has the potential to increase the average age of Army. While this is not necessarily a problem in the first instance, an increase in age may result in a change in key demographic information such as members who are married and have children. This may subsequently decrease individual mobility and increase the need for retention incentives to be directed toward the family unit rather than the individual. In most instances, the personal characteristics of individuals at the commencement of the UFS period will not be the same at the end.

Workforce modelling can show the increased pressures on time-in-rank, promotion backlog and increase in age resulting from larger than normal cohorts. Combined with competition for postings and inflated reporting, there is an increased risk of both a sizeable separation at the end of the UFS period for the targeted cohort, and increased separation in more junior cohorts. These effects can conspire to reduce or negate the effectiveness of a bonus and confound attempts at correcting inadequacies in force structure.

Equity

Remuneration equity essentially requires that individuals doing the same or similar work at a similar standard should get paid, on balance, the same. Equity, and the impact of perceived inequity, appears largely ignored in consideration of bonuses and discussion does not appear in any policy document. Statements such as ‘nobody will be worse off (though some may be better off)’ do little to reduce the impact of inequity in remuneration, although these statements perhaps provide some principled comfort to policy-makers themselves.33

Equity theory has a firm basis in research and, in its simplest form, can be stated as requiring a ‘fair balance to be struck between an employee’s inputs and an employee’s outputs’.34 Employees generally feel that where the inputs to an organisation are the same between two people, they should be treated and rewarded the same, including in the area of remuneration.35 The theory also proposes that at the extreme, a ‘person can always quit a job if it is perceived as too inequitable’.36 It is this extreme outcome that could affect the effectiveness of a bonus.

In general, bonuses paid for any reason other than performance appear to breach the concept of equity and can potentially induce separation within Army. Aside from the extreme case of separation, there are also other potential effects as individuals attempt to reconcile the perceived (or real) inequity to better balance their own remuneration and rewards. These can include reductions in commitment, tolerance and enthusiasm, compared with those on higher levels of remuneration. Relying on the professionalism of the Army individual not to exhibit these effects of inequality is likely to be hopeful at best, misguided and incorrect at worst.

The effect of inequitable remuneration in the workplace is, however, difficult to estimate within Army. Whether an individual is inclined to make a decision to stay or leave Army on the basis of their comparable remuneration with another member performing a similar function but on a different level of remuneration is unknown, as is their functional work output when they are earning a different amount.37 However, it still remains possible that a bonus awarded to one cohort but not another, when the work value is similar, may actually induce separation.38 At the very least a changed self-perception of their work value and personal value to the organisation should perhaps be expected despite the expectation of professionalism.

Reversibility

Regardless of the success or otherwise of a bonus, once offered they are generally not reversible and cannot be easily retracted. Even if the bonus does not address the perceived retention problem, there is little Army can do once the initial offer is made, and Army therefore carries a high risk of failure, if not a high financial risk. Additionally, ‘the ongoing use of retention bonuses can create a culture of expectation that, if not met, may result in a concentrated period of separations from a particular employment group’ in its own right.39 Ironically, therefore, the application of a bonus may induce separations if the expectation of a bonus is not met.

Typically, bonuses are non-binding and still offer opportunities for individuals to discharge during the UFS period and simply pay a pro-rata amount of the bonus back.40 Unfortunately, historical figures are not available on the frequency of this occurrence; however, noting the continued ability of an individual to separate at a time of their own choosing, then accepting the bonus may simply provide nothing more than another administrative hurdle for discharge.41

Paradoxically, the acceptance of a bonus by an entire cohort can actually result in reduced remuneration for many members of that cohort in the medium–long term. If almost an entire cohort accepts a bonus, and a significant reduction in promotion opportunity and increased practical time-in-rank ensues, then some personnel will experience delays in a salary increase commensurate with promotion (or may never get promoted). Depending on the size of the bonus offered, if promotion either does not occur (when previously it would), or is delayed by more than three years due to increased time-in-rank, then these personnel could have been financially better off had a bonus scheme not have been introduced.42 Those who received the bonus and get promoted within a normal career profile would benefit substantially from the bonus scheme, as would those who received the bonus but would not have been promotable anyway.

With the likelihood that negative second-order effects will reduce the effectiveness of bonuses, consideration should be given to better defining a set of circumstances under which bonus should or should not be implemented. Any assumption that bonus initiatives will achieve the desired retention or force structure outcomes should be challenged during deliberate consideration of expenditure on such schemes. This process is neither new nor foreign to Army as all other purchases and contracts follow strict procurement guidelines; the fact that bonuses seem quarantined from these guidelines is curious in that we do not view retention as the procurement of personnel.

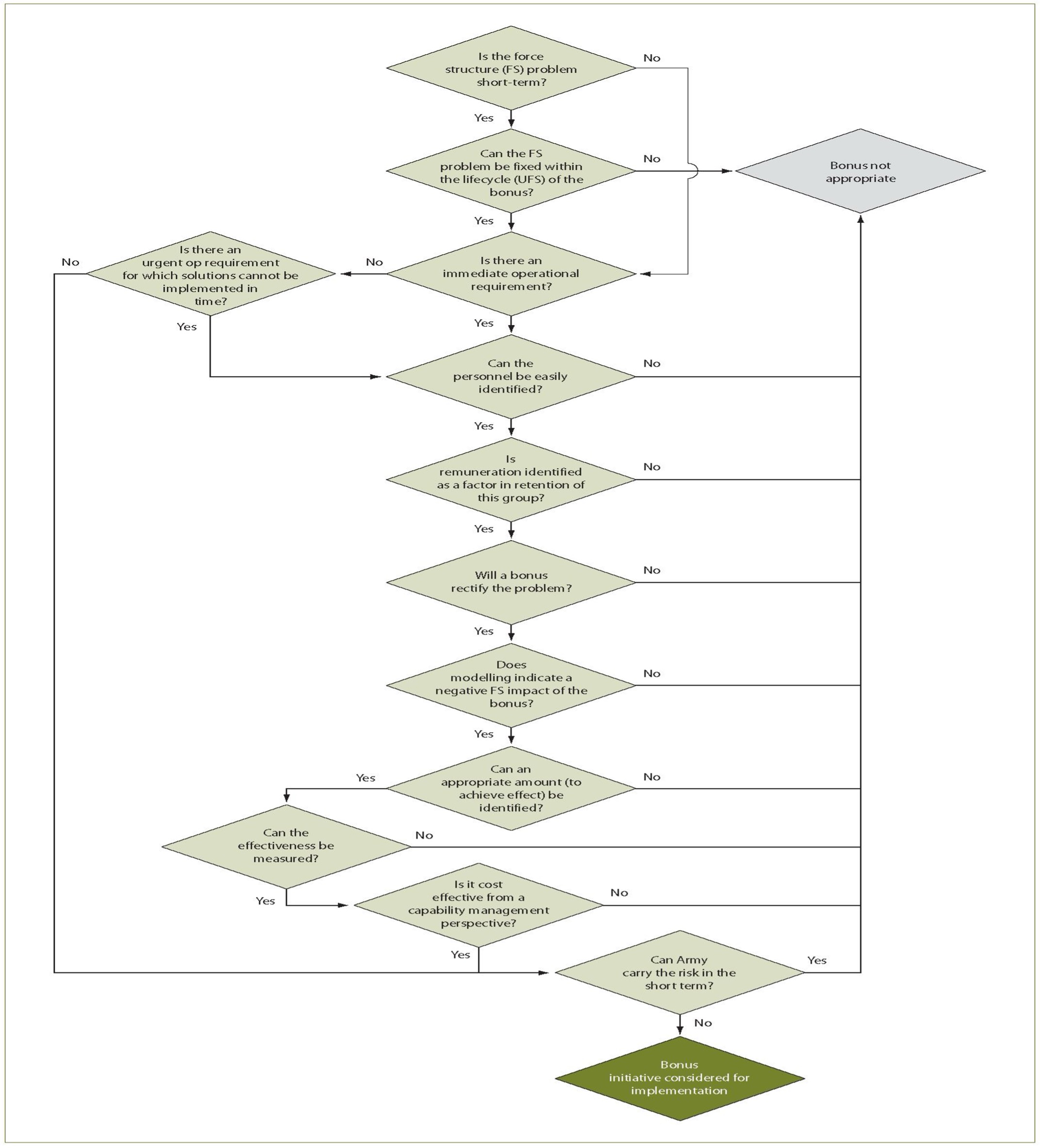

Determining the Appropriateness of a Bonus

Bonuses should not routinely be considered a panacea to retention or force structure problems. Having acknowledged the potential second-order effects, retention bonuses may still provide a valid solution to retention and force structure deficiencies. However, several questions should be asked to determine whether a bonus is appropriate. Figure 4 provides a suggested flow of considerations in determining the appropriateness of a bonus.

If an assessment of bonus initiative considered for implementation results from using Figure 4, then a bonus should be seriously considered. Any other result from using Figure 4 indicates a reduced likelihood of success in the use of a bonus scheme, and subsequent increased likelihood of adverse effects on the force structure. Note, during suggested considerations that even having determined that a bonus may rectify the problem in the short term, consideration should still be given to the cost effectiveness, or whether these funds can be used in other areas known to affect retention.

Conclusion

This article is not intended to downplay the existence of the force structure and personnel deficiencies that have a real effect on the present capability of Army. It does, however, explain that bonuses could be an expensive method to attempt to improve retention where a proven historical precedent does not exist for their success. Furthermore, if remedial action is not taken to correct the underlying deficiencies in force structure during the period of the bonus then the problems will simply resurface after the associated undertaking for further service period has been completed. In this instance, it is possible that funds allocated for use in bonus schemes may be better targeted in areas that are known to affect retention other than remuneration.

Figure 4. Suggested flow of considerations for determining appropriateness of a bonus.

It is always difficult to begrudge any officer or soldier any increase in remuneration whether it be through a pay rise or bonus. Any initiative that results in more money in the pockets of personnel can easily be justified as a good thing. This is almost always true for the individual in the short term; however, over the medium and long term a sudden increase in remuneration through the application of a bonus has effects that may compromise the short-term gain for individuals. Reduced opportunity for promotion, trade structure disruptions, and increased competition for postings are all significant effects of a bonus that confront the individual in the aftermath of the scheme.

The simplistic view of the positive relationship between remuneration bolstered by bonuses and retention rates remains largely ignorant of the possible negative second-order effects and should therefore be challenged. The creation of an inequitable work value remuneration structure, ambiguity in long term effectiveness, introduction of variation in cohort sizes, disruptions to force structure, increases in time-in-rank, increased competitiveness for promotion and postings, and the development of bonus expectations are all reasons not to introduce a bonus. These are all possible negative consequences of the introduction of bonuses, and may all contribute in differing ways to neutralising or reversing the positive effects of a bonus in the medium to long term.

However, notwithstanding the potential negative second order effects of the introduction of a bonus, there may be occasions where there are very few viable alternatives to improve retention. If, for example, there is an immediate and pressing capability deficiency for an existing or pending operational requirement, then the application of a bonus might rectify the deficiency in the immediate short term. On the other hand, if the deficiency is not urgent and there is no existing operational requirement, then bonuses should probably not be entertained as a viable and fiscally responsible solution to capability deficiencies.

Unfortunately, Army will not be able to identify the true long-term benefit of recent retention bonus initiatives for some time. The introduction of other policy changes that are likely to affect the same target demographic as the retention bonus—including the Graded Officer Pay Scale, Graded Other Ranks Pay Scale and Defence Home Owner Assistance Scheme—are likely to confound data analysis. Subsequent analyses may experience difficulty in attributing increased retention to the bonus schemes when it may also have resulted from these other concurrent initiatives.

Endnotes

1 Although the ADF has a long history of bonus schemes, there are no published reports on their effectiveness (or otherwise). The ADF response to Senate Notice Paper Question No. 976 of 14 May 2003 indicates that some bonus schemes have ‘been for short-term specific periods to alleviate operational needs. The continued viability of these schemes past the completion date was not warranted.’

2 In the ADF we do not know the elasticity of wage/retention, that is, we do not know the increase in retention resulting from an increase in salary. This would seem key in understanding the effectiveness of a bonus scheme, and how much needs to paid or budgeted to achieve a particular outcome.

3 Major General (Retd) Barry Nunn, Review of Australian Defence Force Remuneration 2001, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2001.

4 Ibid., p. 126.

5 Ibid.

6 Retention of Military Personnel, Report Number 35 1999–2000, Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, 2001, p. 13, <http://www.anao.gov.au/uploads/documents/1999-00_Audit_Report_35.pdf > accessed 14 May 2008.

7 Ibid., p. 38.

8 Ibid., p. 39.

9 Ibid., p. 58.

10 Ibid., p. 59.

11 Ibid., p. 41.

12 Retention of Military Personnel Follow-up Audit, Report Number 31, 2003–03, Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, 2003, p. 30.

13 Ibid., p. 32.

14 ADF currently promotes a comparison calculator as a means by which individuals can compare their comparative salary, taking into account some of the benefits of service.

15 By offering a bonus, Army is effectively trying to buy any other reasons for leaving from an individual.

16 Attempting to apply large enough bonuses to retain all target personnel is likely to be cost prohibitive. Some personnel will desire to separate from Army regardless of remuneration, unless an unreasonable amount or unreasonable conditions are offered. Approaches to align bonuses with remuneration for equivalent civilian employment are also likely to be problematic where no equivalence exists.

17 The seemingly arbitrary nature of setting bonus amounts does not seem congruent with the fiscal processes of other Defence spending.

18 There may exist an unquantifiable human factor of individuals not wanting the private indignity of both rejecting an offer and still serving for the same duration as those who accepted the bonus. These individuals may perceive that they have ripped themselves off and will actively avoid this feeling by seeking discharge.

19 Army Personnel Working Group details the current critical trades. DWMFA-A provides data on the separation rates for each employment category number (ECN). Of the trades listed on the critical trade list most are either small trades, rely on internal transfers for manning, or have a poor force structure. Only a small group suffer from separation rates significantly higher than the Army-wide separation rates.

20 US Army Officer Retention Fact Sheet as of 25 May 2007 indicates a ‘loss rate’ of 8.5% for second lieutenant to captain compared with the Australian Army’s 8.6% for captain and 3.1% for lieutenant (correct as at May 2008). This is despite the US Army implementing stop-loss policy during the war in Iraq and benefiting from a favourable 20-year pension option; <http://www.armyg1.army.mil/docs/public%20affairs/Officer%20Retention%20…; accessed 11 June 2008. Other sources point toward West Point loss average of 30.4% after their five year initial term; Jaron Wharton, ‘The Real Story of Army Junior Officer Retention’, HumanEvents.com, <http://www.humanevents.com/article.php?id=26525> accessed 11 June 2008. Australian Federal Police also have a comparable separation rate ranging from 5.38–10.13% which is significant given the differences in family disruption; Jessica Lynch and Michelle Tuckey, Understanding Voluntary Turnover: An Examination of Resignations in Australasian Police Organisations, Australasian Centre for Policing Research, Payneham, 2004, <http://www.acpr.gov.au/pdf/ACPR143_1.pdf> accessed 11 June 2008.

21 As at February 2006 there were 3,564,100 people between the ages of 20–34 who worked at some stage during the year. Of these, 2,311,100 had more than one year with their current employer. The remainder either had less than one year (580,300), or were not currently employed as at the census date. This represents a mobility of somewhere between 16.4% and 35.2% which exceeds Army separation rates; 6209.0 – Labour Mobility, (Reissue), Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 2006, <http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/6B390377F3B213…;, accessed 4 June 2008.

22 Emily Jacka, 2006 Australian Defence Force Exit Survey Report – Reasons for Leaving, DSPPR, Canberra, 2007, p. 135 indicates that the response ‘To make a career change while still young enough’ is rated as number two on the list of reasons for discharge in 2006.

23 Exit surveys do not place remuneration in the top ten reason for leaving with exception to the response ‘Little financial reward for what would be considered overtime in the civilian community’ rated at 10/10 for ARA; Ibid., p. 18. The response ‘More attractive salary package available in civilian employment’ was rated at 26/115; Ibid., p. 136.

24 Application of a bonus occurs as part of a personnel system and as such can be analysed using models such as Hill/McCaskey. Linda Hill, A Note for Analyzing Work Groups, Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, Revision 1998, p. 16.

25 The average cohort size of 267 also includes SSO and other non-GSO specialists. Hence three officers effectively represents more than one per cent. Directorate of Workforce Modelling, Forecasting and Analysis - Army, ‘Status Reports, April 08’, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2008. A similar principle applies to corporals and sergeants where cohorts consist of 680 and 350 personnel respectively.

26 Unfortunately, cohorts in Army are sometimes so small that statistically significant evidence would be unlikely.

27 Labour economics describes the occurrence where someone is paid more than he/she would be willing to work for as the ‘economic rent’.

28 Lieutenant Colonel Paul Robards, Analysis of Retention in the First 12 Months of the Army Expansion and Rank Retention Bonus’, DWMFA-A, Canberra, 2002, para 18. Initial indication from the AER and RRB show that the premium may have been as high as $285k per additional person retained under the assumption that the bonus and not other factors were responsible for retention.

29 DRB49 and Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines explain in detail the principle of ‘value for money’ although the context of procurement in human resources is slightly different, the concepts remain valid. Corporate Services and Infrastructure Group, Defence Reference Book 49 Practical Procurement and Prompt Payment P4 Manual, Version 1.1, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2005, p. 11.

30 DWMFA-A data on ‘propensity to leave’ indicates that CDPs for officers occur at year 4, 6, 10 and 13/14. These coincide with lapses in ROSO for RMC direct entrants, ROSO for ADFA graduates, promotion to major, and selection for CSC respectively. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Robards, ‘Propensity to Leave and Workforce Forecasts’, DWMFA-A, Canberra, August 2006.

31 Ibid., Figure 3, p. 3.

32 Posting related reasons for discharge in Army include: ‘Desire to stay in one place’ at number 1 and ‘Probable location of future postings at number 9. Promotion related reasons for discharge include: ‘Better career prospects in civilian life’ at number 7, ‘Insufficient opportunities for career development’ at number 17, and ‘limited promotion prospects’ at number 29. Jacka, 2006 Australian Defence Force Exit Survey Report – Reasons for Leaving.

33 Military and political leadership, in discussion of remuneration, often use the ‘nobody will be worse off’ in defence of policy, including General Peter Cosgrove in his address to the Media Watch Lunch at the National Press Club, Canberra, 30 July 2002; <http://www.defence.gov.au/media/2002/300702.doc> accessed 4 June 2008.

34 See ‘Adams’ Equity Theory: Balancing Employee Inputs and Outputs’, <http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newLDR_96.htm> accessed 14 May 2008. Equity Theory was originally proposed by John Stacey Adams in 1963.

35 See Alan Chapman, ‘Adams’ Equity Theory’, <http://www.businessballs.com/adamsequitytheory.htm> accessed 14 May 2008.

36 Paul M Muchinsky, Psychology Applied to Work, 7th edition, Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, California, 2003, p. 380.

37 It is also not cultural to ‘complain’ openly about someone else receiving a higher level of remuneration. The question of salary or remuneration inequity is not formalised in exit or attitude surveys. Many personnel would most likely not begrudge another person a benefit in any case.

38 If even 1–2 per cent of a trade are induced toward separation as a result of remuneration inequity then it will compromise the effectiveness of a bonus.

39 ‘Critical Personnel Shortages - Navy Retention Bonuses’, Budget Estimates Supplementary Hearing, 21 November 2002.

40 Retention of Military Personnel, p. 59 provides some anecdotal evidence of this occurring in the US military.

41 Robards, ‘Analysis of Retention in the First 12 Months of the Army Expansion and Rank Retention Bonus’, para 11, indicates that there were twenty-eight resignations in first twelve months of the AEB and RRB from personnel who had accepted the bonus.

42 If a fully qualified corporal, with two years or more time-in-rank, is delayed from promotion to sergeant by three years, then he/she would have missed a total salary increase of around $21,000 notwithstanding present-value-of-money, indexing, or any other adjustment. A fourth year without promotion would increase the lost salary to almost $29,000 indicating that a four-year delay in promotion for a bonus less than $30,000 could actually disadvantage members after taking into account NPV calculations.