Religious Diversity in the Australian Army: The Next Diversity Frontier?

Abstract

A diverse workforce has been identified as a critical component of Army’s future capability. However, strategies to increase the proportion of under-represented groups have only been developed for a few discrete and highly visible demographics. This article introduces the topic of religious diversity in Army by outlining the current representation, comparing this against historic and national trends and listing compelling reasons for its consideration by strategic workforce planners in the future. Finally, the article describes the range of benefits that would result from an increase in Army’s proportion of personnel affiliated with religions other than Christianity (currently just 1.2% against a national proportion of 7.2%).

Introduction

Over the last decade Army has seen an increasing emphasis on diversity, including strategies for the recruitment and retention of women and indigenous personnel.1 There is no doubt that these are necessary and important from a variety of perspectives ranging from maximising the possible candidate pool, reflecting the values, demographics and expectations of the wider Australian community, and ensuring that Army is well placed to remain a balanced and focussed organisation. However, despite an emphasis on resolving the gender balance and increasing the number of indigenous personnel in the Australian Regular Army, the lack of religious diversity has gone largely unnoticed.2

That Army’s religious diversity has attracted little attention is something of an anomaly in the current climate, particularly given that the extent of under-representation is relatively large and comparatively visible.3 Frequent deployments to, and multilateral exercises with countries with high proportions of Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus have not yet attracted a wider narrative concerning Army’s lack of religious diversity and any limitations this may place on its ability to operate effectively.4 However, this is unlikely to remain unnoticed for much longer and the need to address aspects of religious diversity is gaining momentum. Nationally, this has been recognised in the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper which, in reference to cultural and religious diversity, states that ‘there are gaps in participation in some of Australia’s institutions and organisations, such as in our parliaments, businesses, labour movement and civil society organisations.’5 The 2013 Defence White Paper notes that, within Defence, ‘specific activities are underway for improved recruitment of women and diverse groups … from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.’6 In addition, the 2012–17 Defence Corporate Plan describes the strategic target of increasing the ‘representation of women and multicultural Australians to better reflect [the] Australian community.’7 In many respects the strategic intent to increase religious diversity might already exist, but this has not yet permeated through other aspects of Army’s policy.

This article introduces the case for a more deliberate approach to religious diversity in Army. While strategies for increasing religious diversity are not presented, the article discusses differences between Army and the broader population, the recent history and trends within Army, and describes opportunities that may result from increased religious diversity. Finally, in order to inform a broader dialogue, this article closes with a short discussion on whether Army should proportionately reflect the demographic characteristics of the nation or simply reflect its values. This article argues that, once Army has progressed its gender and indigenous personnel strategies, there may be sound justification for focussing more on religion as the next possible diversity frontier.

Why we need religious diversity

In 2012 the Australian Human Rights Commission released its Review into the Treatment of Women in the Australian Defence Force (also known as the Broderick Review).8 While religious diversity is not addressed in the review, many of the reasons offered for increasing the representation of women are equally applicable to increasing the proportional representation of any demographic group. Specifically, the review identified five reasons to support its argument that ‘a change in the treatment of women must be a priority for a strong and sustainable ADF’:9

- to attract the best talent

- to reduce costs

- to increase capability

- to be a first class and high performing employer

- to take a [national] leadership position

These reasons also resonate with the need for religious diversity, although there are further capability-related factors including the need to:

- gain a deeper and more intimate cultural understanding and appreciation of local populations in likely areas of future operations, including religious sensitivities and practices (beyond that possible through cultural awareness training during force preparation)

- maintain, within Army, a religious advisory capacity to enhance international understanding during coalition operations, multinational exercises and other activities where diverse religions are represented in an international task force

- enhance the effectiveness of domestic disaster relief programs through consideration and understanding of religious customs, traditions and immediate faith-related needs in affected areas

- increase the potential candidate pool for enlistment in the Army from an under-represented demographic segment

- increase the attractiveness of Army as an employer and career option

This combination of factors provides the imperative for increasing Army’s religious diversity: it will improve operational capability, international engagement capacity, and social balance.10 A positive and likely second-order effect is that it will also improve Army’s national and international reputation as a diverse and inclusive organisation that more closely reflects the Australian society it represents and is able to adapt to a wide variety of religious and cultural scenarios.11

An emerging priority for religious diversity

Unlike other areas of diversity currently being addressed by Army, there are very few strategies that focus on religious diversity.12 There may be several reasons for this, not the least of which could be the absence of a current political or social imperative. In the short term this is unlikely to change as religious advocacy groups in Australia tend not to pressure the government on issues such as proportional representation in the military, nor are there any pressing internal reasons to explore religious diversity.13

This lack of political and internal pressure is unlikely to persevere for another decade, especially since the release of policy documents such as the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper and Australia’s Multicultural Policy strongly suggest the need for greater diversity in public institutions.14 As religious diversity increases within the wider Australian population and Army’s gender balance and representation of indigenous people improves, it is possible that other areas of demographic under-representation in Army will attract some attention. As such, internal and external pressure to increase the representation of religious groups should be anticipated.15

Contributing to other pressures may be the practical realities of continued recruiting underachievement. This may draw attention to potential candidate pools that are not well represented in Army.16 For example, in 2011, over 12% of the recruiting demographic aged between 20 and 29 were affiliated with a non-Christian religion, yet this demographic contributed less than 2% of the total recruiting achievement.17 Since the proportion of people affiliated with non-Christian religions is forecast to increase over the next decade it follows that this demographic may provide a growing pool of potential candidates and should feature more deliberately in recruiting initiatives.18 Ultimately, the government is likely to demand strategies to increase religious diversity from Army should it not independently see the need given continued recruiting underachievement.

Current religious diversity in Australia and Army

Religious affiliation in Australia

National religious affiliation is reported in the National Census, the latest of which was conducted in 2011, the same year as the ADF Census. The Census, the findings of which are summarised in Table 1, indicated that, although the population remained dominated by Christian affiliations (61.1%), the proportion of those of no religious affiliation was also large and approached one-third of the population (31.7%).19 The representation of other religious groups, grouped as non-Christian, accounted for the remaining 7.2% of the total population.20

Table 1. National and Army religious affiliation

|

National ADF(Army) Religious Affiliation21 Census 201122 Census 201123 Army PMKeyS24 |

|||

|

No religion |

|||

|

No religion |

22.3 |

36.8 |

40.5 |

|

Unspecified |

9.4 |

2.7 |

- |

|

No religion total |

31.7 |

39.5 |

41.6 |

|

Christian |

|||

|

Anglican |

17.1 |

20.5 |

17.3 |

|

Baptist |

1.6 |

1.9 |

0.8 |

|

Catholic |

25.3 |

24.9 |

24.3 |

|

Eastern Orthodox |

2.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

|

Lutheran |

1.2 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

|

Pentecostal |

1.1 |

1.5 |

0.3 |

|

Presbyterian/Reformed |

2.8 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

|

Uniting |

5.0 |

3.4 |

3.0 |

|

Other Christian |

4.5 |

3.1 |

0.9 |

|

Christian Total |

61.1 |

59.0 |

57.2 |

|

Other non-Christian |

|||

|

Baha’ism |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Buddhism |

2.5 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

|

Hinduism |

1.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Islam |

2.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

|

Judaism |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

|

Sikhism |

- |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Spiritualism |

- |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Other non-Christian |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Non-Christian Total |

7.2 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

Religious affiliation in Army

Army’s religious affiliation was captured from two sources including the ADF Census and the human resource system, PMKeyS.25 Figures shown in Table 1 indicate that Army’s total religious affiliation comprised around 59% Christian and less than 2% non-Christian. Although the proportion of those indicating a Christian affiliation in Army was similar to the broader Australian population, non-Christian and non-religious affiliations varied considerably.26 The proportion of non-Christian affiliation was about six percentage points lower than the wider population, and non-religious Army personnel was around eight to ten points higher.

The relatively low level of non-Christian representation is a point of concern given that there are no obvious barriers to religious diversity in Army. Unlike gender representation, where the recruiting and retention of women has been constrained by cultural and career management barriers,27 and the recruiting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is constrained by selection disadvantage,28 there are no similar barriers to entry that apply uniquely to religious affiliation. Although this may oversimplify the experiences of those seeking to enter the Army, and further research may be required to identify any organisational barriers, it remains unclear why non-Christian religious representation is so low across the board.

Interestingly, this low representation of non-Christian religions is also present among other comparable nations. Figures from the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and the United States of America indicate similar levels of religious under-representation in their armies as shown in Table 2 (although the time period over which figures were obtained differs between countries and between Census and Army figures). It is possible that some of the underlying reasons may be common between nations and that these are reflected in Australia’s figures. For example, concerns about racism within the military or cultural reluctance towards military service, which are significant factors in the UK, may also be factors restricting proportional representation in Australia.29

Table 2. National and Army religious affiliation30

|

National Regular Army Representation Representation United States of America31 |

||

|

No religion |

20.2 |

25.8 |

|

Christian |

76.0 |

73.0 |

|

Non-Christian |

3.9 |

1.2 |

|

United Kingdom32 |

||

|

No religion |

32.3 |

13.5 |

|

Christian |

59.3 |

84.0 |

|

Non-Christian |

8.4 |

2.5 |

|

Canada33 |

||

|

No religion |

23.9 |

- |

|

Christian |

67.3 |

- |

|

Non-Christian |

8.8 |

- |

|

Australia34 |

||

|

No religion |

31.7 |

39.5 |

|

Christian |

61.1 |

59.0 |

|

Non-Christian |

7.2 |

1.6 |

Trends in religious affiliation

National trends and influences on Army

Over the last few decades there has been a three-way interaction at the national level that has seen a decrease in Christian, and increases in non-religious and non- Christian affiliation. The proportion of Christians has decreased from 73% to 61.1%, those affiliated with no religion has increased from 25.1 to 31.7%, and non-Christian affiliation has increased from 2% to 7.2% since 1986.35 These trends, which can be expected to continue in the foreseeable future, will change the demographic characteristics of future recruits and will have a subsequent impact on the diversity of Army. Progressively, there will be fewer recruit candidates of Christian and more of no religious affiliation. There will also be an increase in potential non-Christian candidates; however, historical representation in Army, discussed shortly, suggests that Army’s proportion might not increase without intervention.

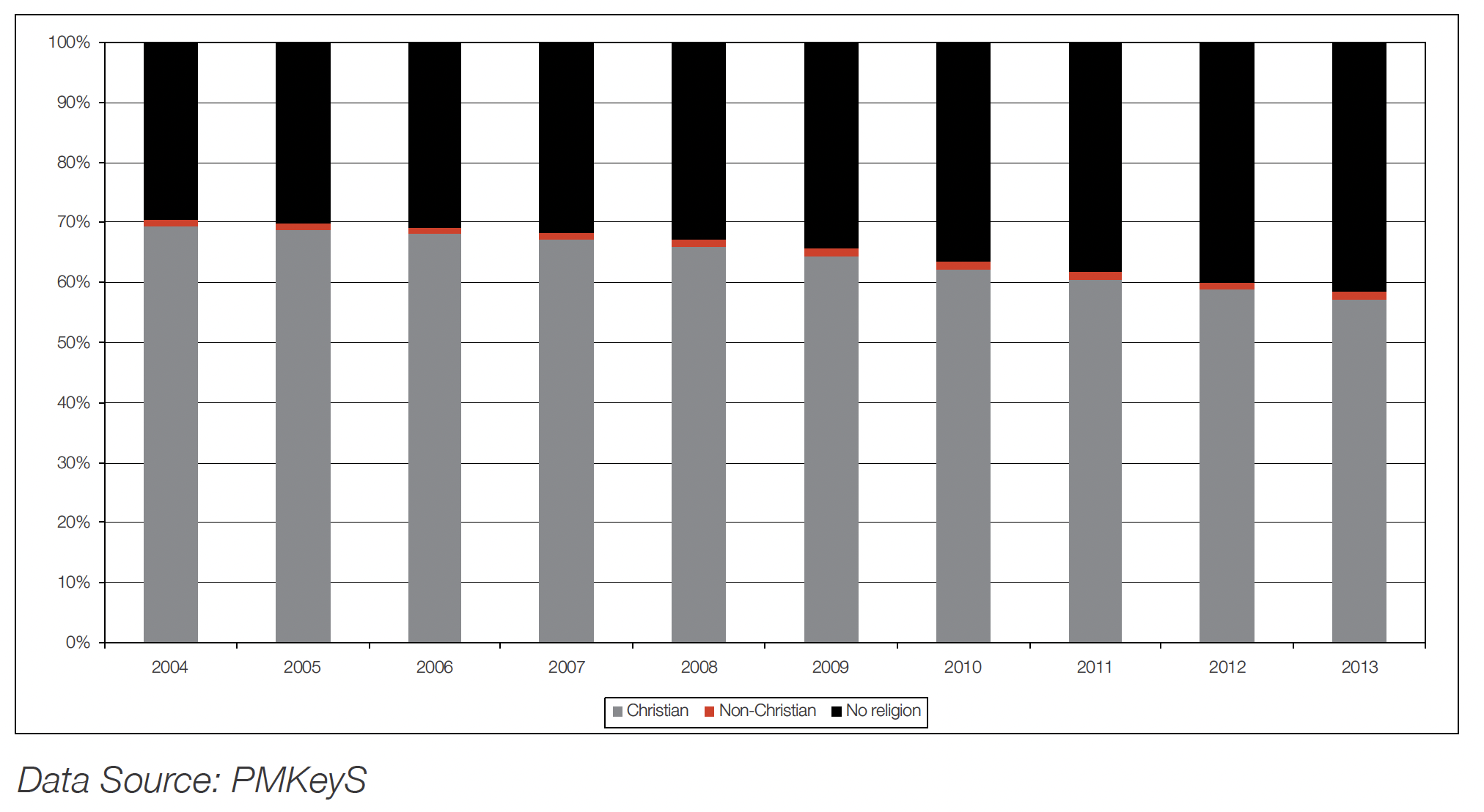

To some extent, the national trends have already been reflected in Army over the last decade, although the size and nature of the change differs. As Figure 1 indicates, in 2004 around 70% of Army personnel were affiliated with Christianity, a number which fell to around 57% in 2013, a decrease of more than one percentage point per year and greater than the corresponding decrease in the wider Australian public (which was around half a percentage point per year). This decrease in Christian affiliation has been matched by an increase in personnel who are not affiliated with any religion, increasing from 29% to around 40%.36 This high rate of change has been influenced by two related demographic factors: the changing religious affiliation of young Australians in the target recruiting ages, and the high proportion of relatively young personnel in Army.37

Although broadly reflected in Army’s Christian and non-religious affiliations, national trends have not been apparent in non-Christian affiliations. Figure 1 shows that the proportion of Army personnel with non-Christian affiliation has remained virtually unchanged over the decade despite increases in the proportion and numbers of Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and others in the wider Australian population. If Army was recruiting effectively across a broad cross-section of society then, all things being equal, non-Christian affiliation in Army should have increased in line with national changes; however this has not occurred.

Figure 1. Religious affiliation in Army 2004–2013

The representation of non-Christian affiliation has been so small that the percentages described in Figure 1 don’t adequately illustrate how little the situation has changed. The raw numbers paint an even bleaker picture of religious diversity in Army. For example, in January 2003 there were 101 personnel who indicated in PMKeyS that they were Buddhist; in January 2013, ten years later, there were 103.

Although there were 33 more Hindus and 22 more Muslims over the same period, their increase in proportional representation can only be measured in fractions of one percentage point which presents a stark contrast to their national increase.38 In total, in January 2013 there were only 340 Army personnel with a non-Christian affiliation of which the largest groups were Buddhist (103), Muslim (48) and Hindu (44).

This lack of non-Christian representation has several implications for Army. Significantly, it portrays Army as lacking the ability to relate to large community sectors on religious grounds; still worse, it points to the fact that Army does not even possess the numbers to reflect a capacity to change. For those members who are serving there are also implications arising from the lack of critical mass which leads to constraints in developing support networks, sharing lived experiences, or even practising their chosen faith in an inclusive Army environment. Their strength is simply too small to adequately contribute to any improvements to capability that religious diversity might otherwise offer.

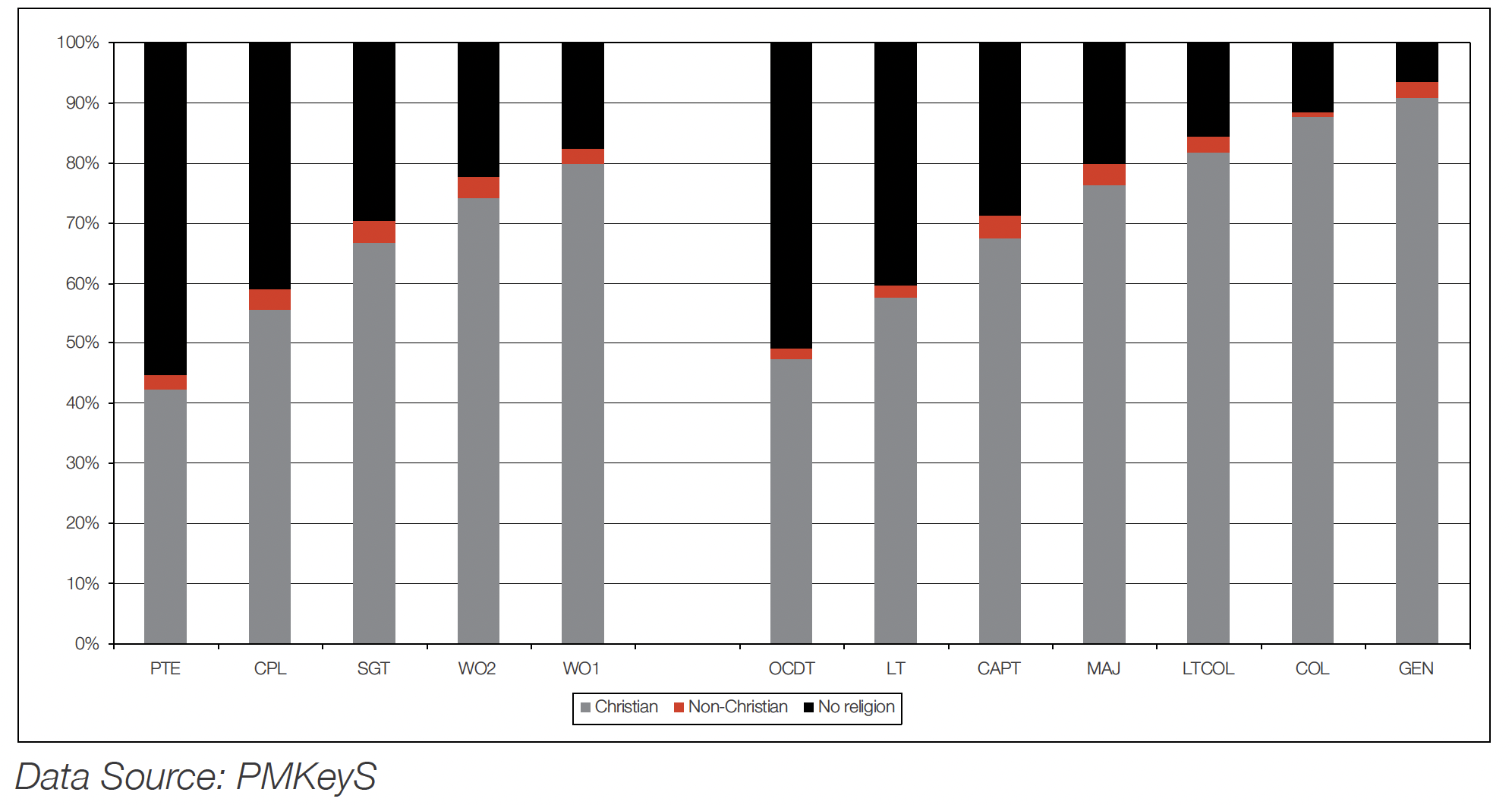

Changes among ranks

Changes in the nation’s and Army’s religious affiliations have also been reflected in differences between ranks. There is clear evidence that junior personnel have considerably different religious characteristics to those of more senior personnel in both officer and other ranks. Over 55% of all private soldiers and 50% of officer cadets had no religious affiliation in January 2013. This compared with just 18% of warrant officers and 6% of generals (brigadier and above). Figure 2 illustrates an incremental increase in religious affiliation as the rank increases from private to warrant officer, and from officer cadet to general.

Figure 2. Religious affiliation by rank as at January 2013

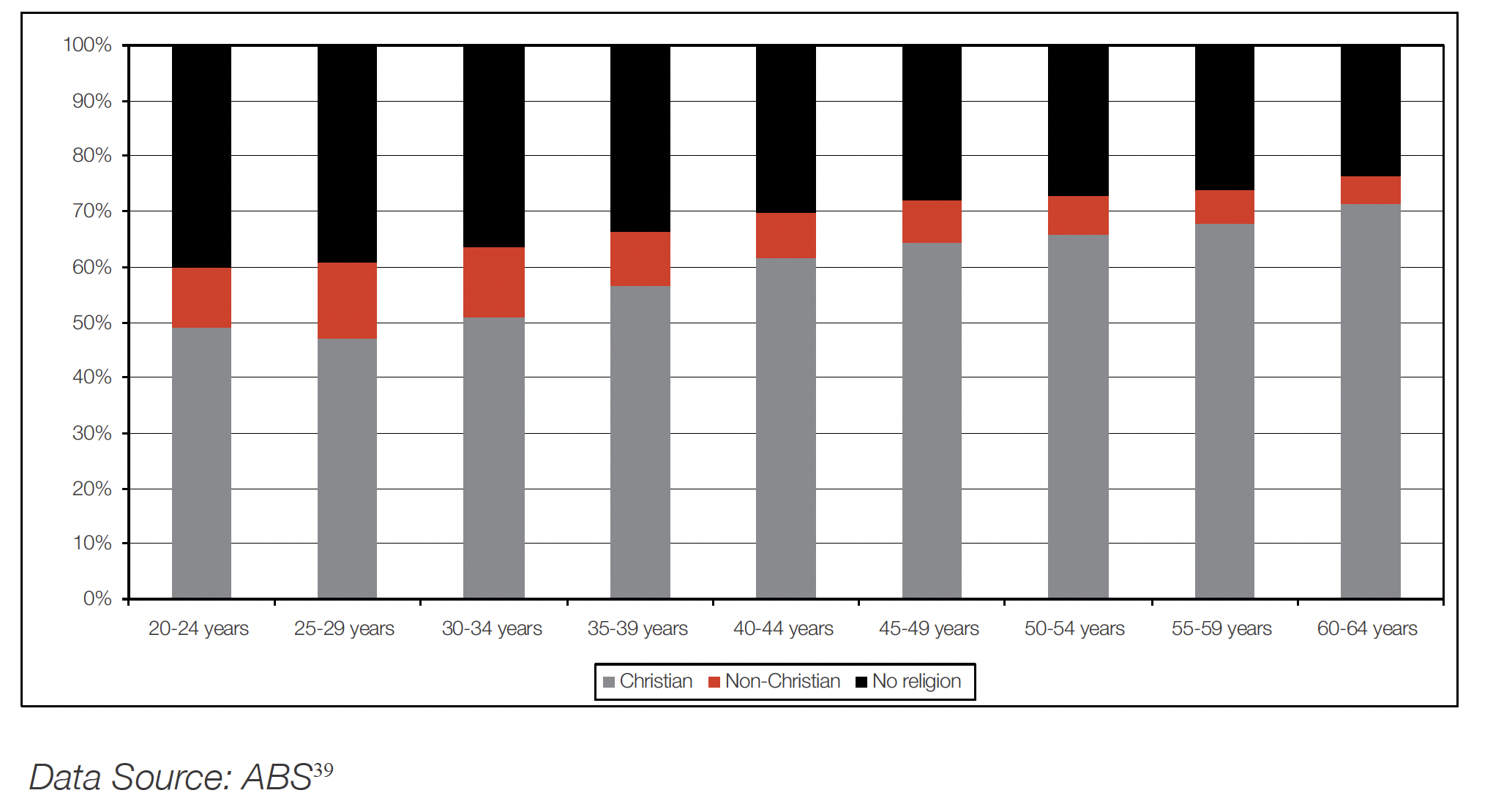

Although there was a noticeable difference in affiliation between the ranks, there was still very little difference in non-Christian affiliation. The proportion of personnel in each rank with a non-Christian affiliation ranged from 1.6% to 3.8% with no evident trend from junior to senior ranks. That the proportion had not increased in the junior ranks is noteworthy when compared to national figures for each age group. Figure 3 shows that the proportion of Australians with a non-Christian affiliation was higher in the younger age groups. This means that, not only is Army unrepresentative in a broad sense, the relative gap is actually increasing in the younger demographic.

It is unclear why there was no increase in non-Christian affiliation in junior ranks. Proportionately, the 2011 National Census showed that, in the key recruiting age demographics, 11% of 20 to 24 year olds and almost 14% of 25 to 29 year olds were affiliated with a non-Christian religion. Army’s proportion in the ranks associated with these ages was just 1.6% of officer cadets and 2.3% of privates. On first principles, if over 11% of 20 to 24-year-old Australians were non-Christian, a similar proportion of Army’s junior ranks should also have been non-Christian; however, Figure 2 shows that this is clearly not the case.

The broad implications of Army’s non-Christian representation have already been outlined; however, the divergence between junior ranks and young Australians is even more significant because it restricts Army’s ability to correct this deficiency. Army’s workforce approach of ab initio recruiting means that religious affiliations that are currently under-represented in junior cohorts will forever remain that way. Even if Army were to increase the proportion of non-Christian affiliated personnel recruited from today, it would take well over a decade for these personnel to be represented both in sufficient numbers to establish a critical mass, and become sufficiently promoted to provide the advocacy necessary at the middle ranks.

Figure 3. Religious affiliation in Australia by age group (2011 Census) Future direction of trends in religious affiliation

The changes in Army’s religious affiliation over the last decade, combined with both the different affiliations between ranks and the trends in the national population, suggest that, in the coming decade, Christian affiliation will continue to decrease and the proportion of those with no affiliation will increase. As over 50% of officer cadets and 55% of privates have no religious affiliation, it is reasonable to expect that by 2040, when these personnel filter through to Army’s higher ranks, at least 50% of Army personnel will have no religious affiliation, including some of the most senior personnel. Religion and religious identity are therefore likely to be less important to a majority of Army personnel over the coming decades than has been the case in the past.

The future proportion of non-Christian affiliation is less clear. As the proportion of junior personnel with non-Christian affiliation is less than 2% there may be very little change in the medium term. Even if the proportion of non-Christian recruits increases to reflect the proportion in society then the change will be gradual over many decades. However, since there is no impediment for Army (or the Australian Defence Force) to alter its recruiting strategy, it is unlikely that non-Christian affiliation will keep pace with changes in the wider Australian population without intervention, thus resulting in a widening gap. Nonetheless, if Army can address the under- representation of non-Christians then several future opportunities may be presented.

Future opportunities

An increase in non-Christian representation in the Australian population presents Army with several opportunities relating to achievement of recruiting targets and the subsequent benefits of a diverse workforce. At the last National Census there were around 370,000 adults in the key 21 to 29-year-old age group; therefore, there is likely to be an existing pool of potential candidates from which Army is yet to draw to contribute to achieving its recruiting targets. Army routinely falls short of its target for many employment categories and it seems intuitive that if there is a large section of the community that is not widely represented, then recruiting underachievement can be minimised simply through recruiting from this demographic.40

A certain critical mass of religious diversity will also enhance Army capability. The deployment of personnel familiar with the religious practices in the area of operations will assist communication, removal of cultural barriers, and other human factor aspects of overseas deployments. Such religious diversity will not only assist in improving international engagement and the ability to operate in combined operations and exercises, it will also assist in understanding an adversary and avoiding the possibility of antagonism and hostility resulting from religious insensitivity.41 Nationally, Army also stands to benefit significantly from an outward appearance of tolerance and inclusiveness that will contribute to its reputation as a socially balanced and responsible organisation.

Regardless of how the opportunities presented through religious diversity are viewed by Army, the current representation of non-Christian affiliated groups appears to be well below that which might be considered reasonable to capitalise on any opportunities. Even after accounting for a possibility that many religious groups may have an adverse view of military service, the current number of 340 non-Christian affiliated people is probably below a critical mass for representation, exacerbated by the geographic dispersion of Army. Based on national representation, around 2000 Army personnel (i.e. 7%) should be affiliated with a non-Christian religion (and even this might not reach a critical mass). However this raises the question of how Army should reflect society and whether it is appropriate or necessary for Army to have a proportion of non-Christian affiliated members that reflects the national level.42

Reflecting Australian society

Whether and how Army, or any service, should reflect society is a question that is not infrequently discussed.43 Detailed discussion is outside the scope of this article, but a broad outline of the central tenets of some selected literature may be useful. In short, there are two prevailing views on representation which have been described as either statistical (i.e. proportional) or ‘delegative’. ‘Delegative’ representation occurs ‘where members of groups are represented in the ranks of any profession by some of their members’ but not necessarily represented proportionately.44

Typically, Army takes the former view — that it should reflect society in terms of its proportional representation.45 For practical reasons, proportional representation is not always achievable because of the differing propensity of some demographic groups to join the military. Any cultural reluctance to join may be based on a variety of factors such as the esteem in which military forces may be held or perceptions of racism; regardless, such attributes have the potential to restrict goals of proportional representation.46 Therefore, although proportional representation might be a simple, intuitive and attractive objective, more analysis concerning the practicalities of such objectives may be required.

The latter view, that an army can reflect the values of society without necessarily resembling it, could be appropriate when considering religious diversity. Dandeker and Mason argue that ‘if proportional representation proved to be unattainable … perhaps delegative representation would offer a more promising way forward.’47 In other words, should there be no feasible likelihood of proportional representation being achieved in the short, medium or long term, perhaps a critical mass of representation would achieve the same diversity outcome. If this view is adopted then there may not always be a need for a recruiting quota system or targeted recruiting initiative. Instead, a more measured approach that would facilitate and allow the recruitment of a greater number of under-represented personnel could be implemented.

Although a solution to achieving the best diversity objective for the Australian Army is not presented here, the current numbers suggest that, not only is Army significantly under-represented in the proportional sense, there are also too few people with non-Christian affiliation to achieve delegative representation. In this regard, any medium-term objective of increasing representation to anything greater than current levels will require a significant net increase in the number of non-Christian personnel that, in all likelihood, could only result from some form of deliberate recruiting and/or retention action. What the non-Christian diversity objective should be is open to further analysis but a figure higher than current levels of under 2%, but less than 7% could be considered reasonable.48

Conclusion

There are many advantages to be gained from increasing religious diversity in Army ranging from the strategic to those that are more practical in the conduct of everyday activities. A reasonable proportion of personnel from a diverse range of religions will allow an intimate appreciation of religion that can contribute to Army’s effectiveness on both domestic and international operations. Furthermore, it will improve Army’s national and international reputation as a diverse and inclusive organisation. Finally, strategies to increase diversity will provide an opportunity to reach into a potential candidate pool for the achievement of recruiting targets. In combination, these advantages are likely to improve Army’s operational capability, international engagement capacity and social balance.

Whether armies should reflect the demographic composition of society or simply represent the values of society without necessarily maintaining proportional representation, is a valid topic in itself. Currently, non-Christian affiliations are significantly under-represented and it can be argued that Army neither reflects nor represents the wider Australian community. Therefore, Army is unable to capitalise on the opportunities and benefits that religious diversity provides. Given the emerging emphasis on diversity in strategic guidance, the option not to address religious diversity may not exist for much longer and strategies to address this now require consideration. As a first step, Army must have a discussion about the level of representation needed to reflect the values of society. Having established this level, Army will be in a position to begin to address religious diversity thereby capitalising on the resulting opportunities and avoiding the political and social scrutiny that may otherwise result.

Endnotes

1 For indigenous people strategies see, for example, Australian Army, Chief of Army Directive 02/12 Army Indigenous Strategy, Army Headquarters, Canberra, 2012; Department of Defence, Australian Defence Force Indigenous Employment Strategy 2007-17, Canberra, 2007. For gender strategies, see, for example, Australian Army, Chief of Army Directive 15/12 Army Implementation Plan for the Removal of Gender Restrictions, Army Headquarters, Canberra, 2012; Australian Army, Chief of Army Directive 16/12 Enhancing Capability Through Gender Diversity, Army Headquarters, Canberra, 2012; Department of Defence, Pathway to Change: Evolving Defence Culture, Canberra, 2012.

2 There are no current strategies concerning religion in the ADF. The diversity area of the ADF’s website only briefly mentions religion and the link contains simply a guide to religious belief. See Department of Defence, Canberra, ‘Religion and Belief’ at: http://www.defence.gov.au/fr/rr/ religion.htm (viewed 4 July 2013).

3 Photographs of deploying troops are dominated by young, white males with almost no evidence of the wearing of headdress and garments associated with some religions despite it being permitted in the dress manual: see Australian Army, Army Dress Manual, Army

Headquarters, Canberra, 2013, Chapter 2, pp. 14-17. For example, a search using ‘parade’ on the website Australian Defence Image Library on 4 July 2013 shows no religion-specific items of dress and demonstrates the general demographic of Army personnel. See: http://images. defence.gov.au/Fotoweb/search.fwx

4 For more information on religious representation see CIA World Factbook at: https://www.cia. gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook

5 Australian Government, Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, Canberra, 2012, p. 101.

6 Australian Government, Defence White Paper 2013, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2013,

p. 101.

7 Department of Defence, 2012–17 Defence Corporate Plan, Canberra, 2012, p. 36.

8 Australian Human Rights Commission, Review into the Treatment of Women in the Australian Defence Force: Phase 2 Report, Canberra, 2012.

9 Ibid., p. 43.

10 For a discussion on the use of cultural knowledge in operational planning see E. Bledsoe, The Use of Culture in Operational Planning, Masters Dissertation, United States Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, 2000. The benefits of increased military cultural

training in reducing cultural stress are detailed in J. Azari, C. Dandeker & N. Greenberg, ‘Cultural Stress: How Interactions With and Among Foreign Populations Affect Military Personnel’, Armed Forces & Society, 36(4), 2010, pp. 585–603.

11 This has been described as ‘social legitimacy’ by V. Aziz, ‘Effecting Discrimination: Operational Effectiveness and Harassment in the British Armed Forces’, Armed Forces & Society, 34 (4), 2008, p. 729.

12 There are some dated policy documents such as Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (General) Personnel 26-2 Australian Defence Force Policy on Religious Practices of Australian Defence Force Members, Canberra, 2002; Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (General) Personnel 35-5 Defence Multicultural Policy, Canberra, 2002. There are also guidelines such as Department of Defence, Guide to Religion and Belief in the Austraian Defence Force, Canberra, 2012. However, there is no strategy for proportional representation.

13 Although the Defence Diversity and Inclusion Statement released in March 2013 explicitly defines religion in its definition of diversity, there are currently no ethnic or religious diversity strategies in the ADF. The ADF’s Human Resource Metrics System, which has recently included a diversity reporting area, only provides detailed reports on women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, but aggregates the ‘Culturally and Linguistically Diverse’ due to an inability to provide more fidelity.

14 See Australian Government, The People of Australia, Australia’s Multicultural Policy, Canberra, 2011; Australia in the Asian Century White Paper.

15 Although religion is not mentioned explicitly, in so far as religion is associated with multiculturalism the Australian government’s multicultural policy emphasises the importance of diversity. It is policies such as these that will direct Defence multicultural policies including the recruiting and retention of personnel. See Australian Government, The People of Australia, Australia’s Multicultural Policy.

16 Army routinely fails to achieve its recruiting target. See F. Pinch, ‘Diversity: Conditions for an Adaptive, Inclusive Military’ in F. Pinch, A. MacIntyre, P. Browne & A. Okros (eds), Challenge and Change in the Military: Gender and Diversity Issues, Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, Kingston, 2006, pp. 171-192. Pinch notes that, in the Canadian Forces context, ‘there had to be a great deal of interpenetration and boundary permeability between the military and society

… where the military had to rely on the human resource pool and the support of the public to sustain itself.’ (p. 173). Achievement of targets in Australia may reveal a similar reliance on a more diverse range of community sectors.

17 National data obtained via the ABS Survey TableBuilder available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder Fields used were AGE5P – Age in Five Year Groups and RELP – religious affiliation. Table developed and last viewed on 27 June 2013. Defence data obtained from the PMKeyS Data Warehouse with crosstabs of age and religion.

18 Ibid.

19 The ABS defines ‘no religion’ as those indicating both ‘unspecified’ or ‘no religion’.

20 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cultural Diversity in Australia, Reflective of a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+featur es902012-2013 (viewed 29 March 2013).

21 Religious affiliation is defined in Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1266.0 - Australian Standard Classification of Religious Groups, 2011, Canberra, 2011.

22 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cultural Diversity in Australia.

23 Roy Morgan Research, Report on 2011 Defence Census, Department of Defence, Melbourne, 2012, p. 212. Rounding error produces a total of 100.1%. Army-specific data provided by Ms Ruth Beach, Directorate of Strategic People Research.

24 Data extracted from PMKeyS on 13 Mar 2013, correct as at 1 Jan 2013.

25 Personnel Management Key Solutions, or PMKeyS, is the ADF’s human resource information system.

26 There has been a proliferation of terms relating to the spectrum of those who have no religion including anti-theist, atheist, agnostic, irreligious, ignostic and free-thinking among others.

The sources of data on religious diversity, which include the National Census, ADF Census and Army human resource data, all included options for a non-religious/unspecified affiliation, also termed ‘no religion’. For comparison, Army figures for ‘no religion’ include atheists, agnostics, those who indicated ‘no religion’ and those who did not specify a religion.

27 Australian Human Rights Commission, Review into the Treatment of Women in the Australian Defence Force, pp. 74–83.

28 Department of Defence, Australian Defence Force Indigenous Employment Strategy 2007-17, Canberra, 2007, p. 2.

29 See A. Hussain, ‘The British Armed Forces and the Hindu Perspective’, Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 30 (1), 2002, pp. 197–212; A. Hussain, ‘British Pakistani Muslims’ Perceptions of the Armed Forces’, Armed Forces & Society, 28(4), 2002, pp. 601–18.

30 Due to differences in census dates and military reporting the figures in Table 2 do not reflect the same year. Rounding error also applies.

31 United States Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, Section 1, p. 61, at: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population.html (viewed 9 July 2013). US Army data obtained from Deputy Chief of Staff – Army G1 courtesy of Lieutenant Colonel Firman Ray, Strength Forecasting and Analysis.

32 United Kingdom Statistics Authority, Detailed Characteristics for England and Wales, March 2011, Statistical Bulletin, Office for National Statistics, 2013, p. 15 at: http://www. ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_310514.pdf (viewed 9 July 2013). UK Army data is available from Ministry of Defence, Biannual Diversity Dashboard: 01 April 2012 at: http://www. dasa.mod.uk/publications/people/diversity/ 20130401_1_april_2013/1_april_2013. pdf?PublishTime=08:30:00 (viewed 1 July 2013).

33 Statistics Canada, 2011 National Household Survey: Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity, Catalogue number: 99-010-X2011032 at: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc- cel?catno=99-010-X2011032&lang=eng (viewed 8 July 2013). Canadian Army data was

not available at the date of publication; however, the 2001 Canadian Census indicated that representation across the entire Canadian Armed Forces at that time was 74.4% Christian, and 1.0% non-Christian (the Canadian representation in 2001 was 76.6% and 6.0% respectively). For national 2001 data see Statistics Canada, ‘Religions in Canada’, 2001 Census: analysis series, Catalogue number: 96F0030XIE2001015 at: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/access_ acces/push_pdf.cfm?FILE_REQUESTED=\english\census01\products\analytic\companion\ rel\pdf&File_Name=96F0030XIE2001015.pdf (viewed 8 July). Canadian Armed Forces data courtesy of Dr Kelly Farley, Chief Scientist, Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis.

34 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cultural Diversity in Australia. Australian Army data available from Roy Morgan Research 2012, Report on 2011 Defence Census, Department of Defence, Melbourne, p. 212. Rounding error contributes to total of 100.1%. Army-specific data provided by MS Ruth Beach.

35 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Religious Affiliation at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf

/46d1bc47ac9d0c7bca256c470025ff87/bfdda1ca506d6cfaca2570de0014496e!OpenDocume nt (viewed 1 July 2013).

36 Although there has been a decrease in total Christian affiliation, the trend is not consistent among Christian denominations. Catholic representation, which is still the largest single denomination in Army, has not changed significantly, decreasing from 28% in 2003 to 24% in 2013. In contrast, the representation of other Christian affiliations decreased from 42% in

2003 to 33% . It is difficult to examine this trend in more detail as there appears to have been a migration away from the Uniting Church, Presbyterian, Anglican and other denominations toward the more generic ‘other Protestant’ affiliation.

37 In the 2011 National Census, 39.6% of 20 to 29 year olds either had no religion or their religion was not stated.

38 Comparisons over the same time-frame are not possible given the census timings; however, between 1996 and 2011 the proportion of Buddhists increased from 1.1% to 2.5%, Hindus increased from 0.4% to 1.3% and Muslims from 1.1% to 2.2%.

39 Data was obtained via the ABS Survey TableBuilder available through the link http://www.abs. gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder. Fields used were AGE5P – Age in Five Year Groups and RELP – religious affiliation. Table developed and last viewed on 27 June 2013.

40 The propensity of people of non-Christian affiliation to join the military may not be the same as others; nonetheless, recruiting opportunities may still exist.

41 Bledsoe, The Use of Culture in Operational Planning.

42 Given a national population of 1.55 million people with non-Christian affiliation, including 370,000 from the recruiting demographic of 20-29 year-olds, a strength of 320 would intuitively seem to be below what might be available from this population.

43 See C. Dandeker & D. Mason, ‘Diversifying the Uniform? The Participation of Minority Ethnic Personnel in the British Armed Service’, Armed Forces & Society, 29 (4), 2003, pp. 481–507; H. Jung, ‘Can the Canadian Forces Reflect Canadian Society?’, Canadian Military Journal, 8 (3), 2007, pp. 27–36.

44 Dandeker & Mason, ‘Diversifying the Uniform?’, p. 488.

45 See Australian Army, Chief of Army Directive 02/12 Army Indigenous Strategy, p. 1.

46 There are several examples of this in the United Kingdom where studies have found that Hindus and Muslims are reluctant to join the military, although some of this reluctance may have resulted from perceived racism. See Hussain, ‘The British Armed Forces and the Hindu Perspective’, pp. 197–212; Hussain, ‘British Pakistani Muslims’ Perceptions of the Armed Forces’, pp. 601–18. Representation is also discussed in Jung, ‘Can the Canadian Forces Reflect Canadian Society?’, pp. 27–36; Dandeker & Mason, ‘Diversifying the Uniform?’, p. 489.

47 Dandeker & Mason, ‘Diversifying the Uniform?’, p. 491.

48 I believe 5% is a reasonable and achievable objective subject to considerations such as propensity to join.