MRS Hannah Woodford-Smith

Director of Woodfordi Group

In his 1979 book Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia, one of Australia’s most eminent scholars of security studies, Professor Desmond Ball, wrote:

In deterring enemy actions against Australia, as well as in military operations against that enemy, it is not the force-in-being or the current order-of-battle that is relevant, but the mobilised force with which the adversary would have to contend; the rate at which mobilisation proceeds with respect to any particular contingency is often the crucial variable … To draw attention to the problems of mobilisation in defence of Australia is not to imply that Australia faces any foreseeable imminent threat to its national security … However, this does not absolve the analyst from consideration of the possibilities. The defence planner, and the public at large, should be aware of the general problems of mobilisation, so as to assess and take the necessary insurance, not because the probability of extreme scenarios eventuating is high, but because forethought and planning could make such an enormous difference in the event Australia was to suffer any large-scale hostilities; indeed, the very existence of such planning and of event preparations for mobilisation might even deter the extreme scenarios from eventuating.[i]

It is worth quoting Ball at length to introduce the subject of mobilisation in the context of Australian land force. In the preface to this same book, Ball draws attention to the crux of Australia’s strategic problem set, and specifically to the issues of mobilisation. He eloquently highlights the strategic context in which contingency planning is a necessity as well as the scenario(s) under which mobilisation planning should occur. Planning responsibility is attributed to the government, to analysts, to defence planners and, importantly, to the public. Finally, in championing the reasons behind mobilisation planning, Ball validates the unique contribution these efforts make to national defence and to a strategy of deterrence. This introduction grounds Ball’s original analysis in the present day and helps frame conversations about the challenges entailed in the national mobilisation, and opportunities we have to plan against them—not just internal to defence, but as a community of security practitioners and academics.

Strategic Context

The Commonwealth War Book of 1956 directs that, during the early stages of a war emergency, Army must ‘make preliminary arrangements for the prospective extent of mobilisation and expansion of the Regular Army Field Force and its employment as an Expeditionary Force, in anticipation of the Government’s approval’.[ii] It is often within the extremes of this context that talk of mobilisation arises. It is a reality that has become particularly evident in light of the Russia-Ukraine War, with many NATO and other European countries raising issues of mobilisation and implementing workforce solutions such as selective service in response to a deteriorating strategic environment across Eastern Europe.[iii] For example, in 2022, the UK commenced Operation Mobilisation to ‘make the British Army ready for war in Europe’, not with the intention of provoking conflict but to prevent it.[iv]

Australia continues to experience the benefits (and drawbacks) of geographic distance and it is not imminently threatened by conflict—domestically or in the region. However, we are faced with the prospect of such a contingency in an environment where there may be no strategic warning for its commencement.[v] Compounding this reality are a range of other factors shaping Australia’s strategic environment, including increased geopolitical tension, advancements in technology, more capable systems, unpredictable climate events, and adversaries that threaten to disrupt current methods of warfare. It is a strategic context defined by uncertainty, and possibly high concurrent demand.

Contingency Planning

In situating this high risk, and uncertain strategic environment, lessons of history provide critical opportunities to learn and assess the types of scenarios that may necessitate Australian mobilisation (and the type of mobilisation referred to). National mobilisation of the military ‘in a time of war’ is not the only context within which the term is applied. The phrase is commonly used by police and, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, by health professionals too.[vi] It is a common term, with a broad and opaque application that, without appropriate contextualisation, can conjure up severe hypotheticals that often begin (rather than end) with population-wide conscription.

In my article ‘Defining Land Force Mobilisation’ in Volume 20 of the journal earlier this year, I defined defence mobilisation as:

the activity, or process, of transition between preparedness and the conduct of a specific military operation. It is the shift from the force-in-being (FIB) at a minimum level of capability (MLOC) to an operational level of capability (OLOC).[vii]

Defined this way, not every mobilisation is a national endeavour. Indeed, national mobilisation in Australia has occurred only twice: in response to the First and Second World Wars. However, other contingencies (like the Vietnam War, Australia’s contribution to INTERFET from 1999 to 2012, and the 2019–20 Operation Bushfire Assist) have required Defence mobilisation at some level and must therefore be included in planning frameworks. Australia’s military history highlights three possible scenarios that are consistent with previous instances of mobilisation—some are more likely than others, whereas others are more dangerous. They comprise:

- Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief tasks domestically and overseas

- Regional security/stability operations

- Major conflict in the region.

At the time of writing, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is not committed beyond its current capability to any of these scenarios. Nor is Australia faced by an imminent threat from such scenarios (despite their inherent unpredictability). However, as Ball suggests, planning against ‘extreme scenarios’, such as those in which Australia faces large-scale hostilities, promises an asymmetric advantage that could position this country to pivot quickly in response to a future threat event, or even to prevent its occurrence.[viii]

Planning Authority versus Planning Responsibility

As Ball suggests, lacking an immediate threat does not absolve contemporary analysts or planners from assessing the possibilities of an insecure future. Rather, Australia’s uncertain strategic reality necessitates their attention and due examination. Indeed, consideration of major power conflict and mobilisation are not far from the minds of Australian Government officials and strategic planners. The terms of reference for the Defence Strategic Review 2023 (DSR) directed consideration of the ‘investments required to support Defence preparedness, and mobilisation needs to 2032–33’.[ix] Further, calls for proactive and whole-of-government planning approaches to national crises were invigorated by the demands placed on ADF capabilities and resources during (and after) the bushfire and COVID national emergencies in 2019 and 2020.[x]

In responding to this reality, the Australian Government released the DSR in 2023 and, in 2024, further refined Australian priorities in the National Defence Strategy (NDS). Though neither document provides direction specific to mobilisation, both deliver foundational principles that would underpin any endeavour to enact it. In particular, the DSR directed the largest recapitalisation of the ADF since the Cold War to support the transformation to an ‘enhanced force-in-being’ by 2025. Such transformation is occurring under the auspices of what the DSR termed ‘accelerated preparedness’—a concept that encompasses ‘additional investment from the Government and much more relevant priority setting by Defence … to enhance the ADF’s warfighting capability and assure self-reliance in National Defence’.[xi] Notably, the NDS also emphasises the concept of ‘National Defence’ as the ‘coordinated, whole-of-government and whole-of-nation approach that harnesses all arms of national power to defend Australia and advance our interests’.[xii]

Such direction is applicable to scenarios beyond what would necessitate a national mobilisation. However, during a national mobilisation, government and public commitment to a holistic approach to the defence of Australia and its interests becomes immediately amplified. Recognising the need for integrated effort is not new: national defence has never occurred in the isolated siloes of defence. But this aspect has been absent in public commentary on national security issues for decades. As the term ‘national mobilisation’ suggests, it is a whole-of-nation effort—one that depends on an all-encompassing approach to national defence, inclusive of the population base.

In this way, the planning authority rests with those tasked and resourced to manage strategic risks—those within government. However, as stated from the outset, there remains a responsibility to engage with mobilisation planning among the public at large.

The Public at Large

As Ball incisively points out, public discourse on mobilisation is equally important as defence and government planning on the matter.[xiii] However, the prospect of further deterioration in Australia’s strategic environment has instigated a debate on mobilisation that, while necessary, is often unduly sensationalist. Conversations in the public domain often conclude in arguments about conscription,[xiv] ‘frightening’[xv] and exaggerated threat assessments and urgent calls to mobilise elements of Australian society now (like our economy[xvi]). These highly sensitive and culturally nuanced topics, particularly mobilisation in extremis, demand delicate attention and strong academic rigour to ensure that assessments are logic based and that decisions concerning mobilisation are commensurate to the risk.

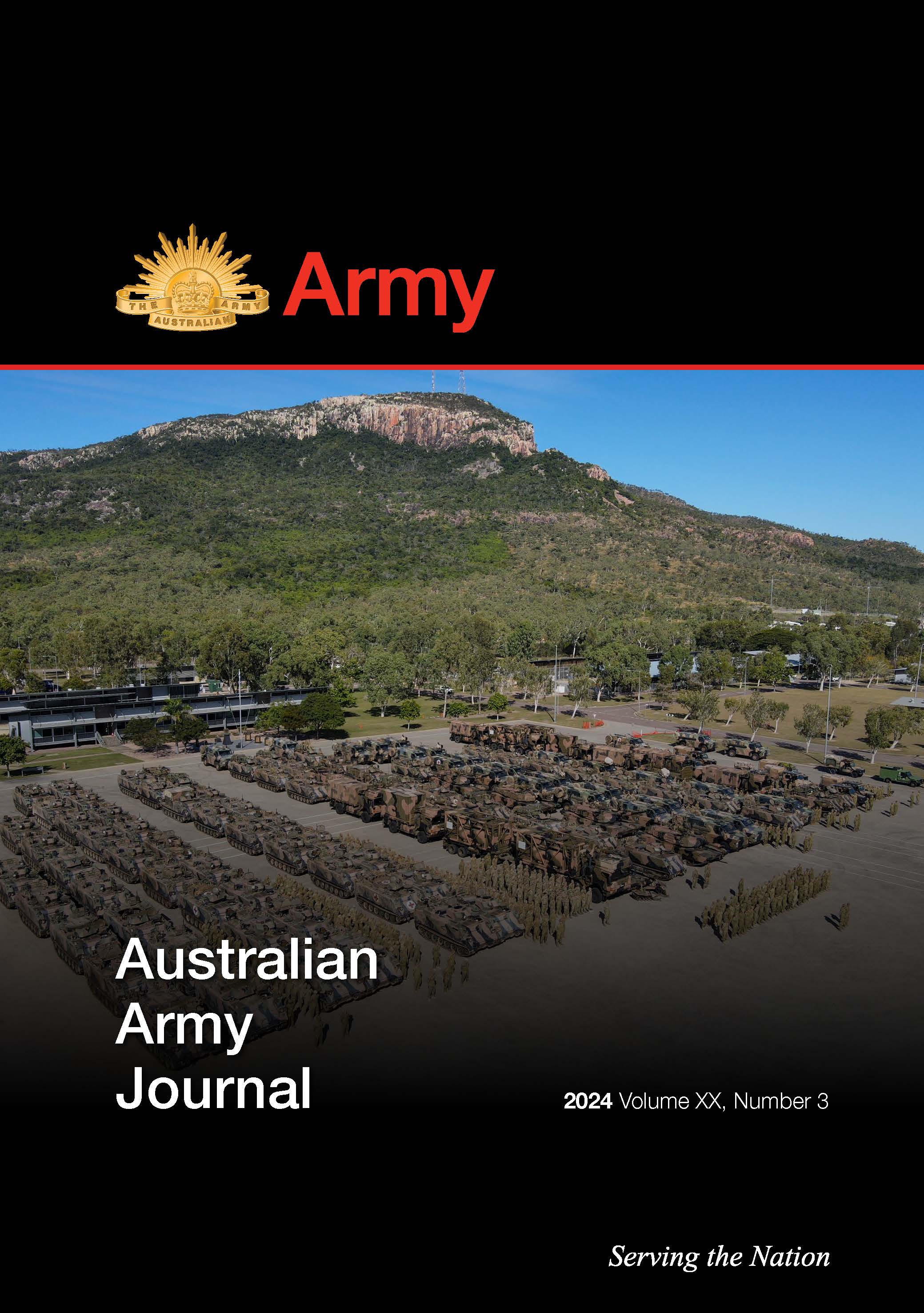

Such an approach is even more critical when discussing the impacts of mobilisation on Army. More than any other arm of the ADF, Army will be the benefactor (or inevitable recipient) of any rapid capability expansion that depends predominantly on humans, as well as on the equipment and support systems required to keep them safe. Herein lies the origin of this themed edition of the Australian Army Journal (AAJ). It represents Army’s contribution to an ever-growing body of literature that is so often about land forces but not from land forces.

AAJ 03-24—Army’s Contribution to Accelerated Preparedness

It is within this context that we launch this series of papers on mobilisation as Army’s third and final edition of the AAJ for 2024. A focus on mobilisation research represents both respect for our past as a military organisation and a hedge against possible scenarios in our future that are consistent with this history.

Setting the historic context for mobilisation, Jordan Beavis, Richard Dunley and Dayton McCarthy draw on Australian experiences prior to and during the Second World War. Beavis exposes a unique aspect of Australia’s approach to mobilisation during the Second World War. Specifically, he provides a detailed historical analysis of the mechanisms Army used and the approach it took to planning for the dispatch of a division overseas for war, ahead of the critical 1939 declaration.

Dunley similarly provides important insights on the niche (but no less critical) topic of the mobilisation of civilian capability during wartime, a theme which remains particularly relevant to the DSR-directed littoral-focused land force. His analysis of ‘ships taken up from trade’ highlights the enduring dependence on maritime transport requirements during wartime of both the economy (for shipping goods) and the military (for moving capability to and from theatre) and the inherent trade-offs made in balancing these demands.

Looking domestically at Army’s preparatory actions for home defence ahead of the Second World War, Dayton McCarthy discusses the foundations laid to expand the militia when it was fully mobilised from December 1941. Dayton’s insightful paper exposes the costs of concurrency Army experienced in attempting to revive a part-time force while raising, training and sustaining the expeditionary/deployed force. These lessons echo key risks to the current Army, and a tension the organisation faces in light of the DSR’s direction for Army Reserve brigades to ‘provide an expansion base and follow-on forces’ that (reading between the lines) is in support of deployed capabilities that are ‘able to meet the most demanding land challenges in our region’.[xvii]

Tom Richardson examines events that are closer in time, are often more emotionally fuelled, and have greater resonance within Australia’s cultural subconscious when remembering times of war. Richardson examines the lessons that Army can draw from the National Service Scheme of the 1960s and 1970s, highlighting it as a mechanism for rapid force expansion but one that does not compensate for shortages in effective officers and experienced regular personnel. These shortages ultimately influence the training capacity of the Army organisation to transition civilians through basic individual and collective training cycles.

In discussing these issues further, Sean Parkes, Hannah Woodford-Smith and John Pearse present a current overview of Army scalability and the Army training enterprise. The authors do so with a view to traditional force expansion methods and the current operating environment. Importantly, they present possible solutions to traditional problems of soldier throughput, including leveraging technology and a dispersed approach to training.

Cassandra Steer similarly considers questions of mobilising capability in Defence, specifically regarding space-related assets. She suggests that Army should be cognisant of the risks associated with dependency on commercial assets, including the potential for poor-quality data and competition for a skilled space workforce. Steer calls for greater sovereign capability and engagement with research and industry sectors. However, many of these recommendations reflect broader changes in the strategic and political environment.

Two papers address this wider strategic context and introduce opportunities to enhance current policy settings to better enable mobilisation. In addressing Australia’s historic defence policy environment and mapping it against current arrangements, Stephan Frühling, Graeme Dunk and Richard Brabin-Smith remind readers of a key recommendation in the Defence Efficiency Report of 1997: ‘The Defence Organisation should be organised for war and adapted for peace’.[xviii] The authors focus on planning considerations for Reserve forces, the role of civilian support, and the necessity for mobilisation systems to be exercised realistically.

Concluding the article contributions within this AAJ, David Kilcullen offers a framework for national resilience, comparing the experiences of Australia’s allies and partners in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War and conflict in the Middle East. In particular, he finds that Australian national resilience and mobilisation efforts in this environment will require a more extensive, robust, well-resourced and whole-of-government approach. Realising this approach will demand continuing this conversation on mobilisation with a multidisciplinary and qualified audience.

As Tony Duus points out in the foreword, providing a platform to continue these discussions is one of the core values of a themed AAJ. It brings together the combination of experienced uniformed, academic and industry voices on a specific (and in this case incredibly complex and emotive) topic. Notably, however, none of the contributors have lived through a national mobilisation and very few have tangibly experienced the effects of force expansion on the Army. It is one of the inescapable facts in dealing with mobilisation practically and conceptually—it is assumptions-based and grounded in lessons learnt by others.

In the penultimate contribution to AAJ 03-24, Shane Gabriel recounts his experiences in re-raising the 7th Royal Australian Regiment in December 2006. This thought-provoking and critical insight into a period of force expansion under the Enhance Land Force Program is essential reading for anyone involved with, or interested in, growing an all-volunteer land force.

Finally, a transcript of the speech given by David Caligari and Zach Lambert to The Cove in October 2022 is provided to highlight the various factors that affect mobilisation. Themes covered include:

- the four stages of mobilisation

- the phases of unit readiness

- fundamental inputs to capability across the four stages of mobilisation.

The AAJ concludes with a series of book reviews on key topics that underpin the Army profession, broadening our collective knowledge base and understanding of our core business.

The contributions to this edition are only the start of the conversation. They are broad in nature, generally historically focused, and draw on findings from the experiences of our allies and partners. It is with this in mind that we call for further academic debate that is oriented away from emotive problematisation of mobilisation towards interdisciplinary research tailored to the Australian land force of the future. It is our whole-of-nation responsibility to constructively contribute to this debate and further the efforts of those tasked with defence planning. In the words of Desmond Ball, doing research or planning on issues such as mobilisation allow us to ‘assess and take the necessary insurance’ that ‘could make such an enormous difference’ should we ever be faced with a threat so extreme as to necessitate its realisation.[xix]

[i] Desmond Ball, ‘Preface’, Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia (Canberra: Phoenix Defence Publications, September 1979).

[ii] Department of Defence, ‘Army Measures’, Commonwealth War Book (Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia, October 1956), p. 6.

[v] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023); Australian Government, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024).

[vii] Hannah Woodford-Smith, ‘Defining Land Force Mobilisation’, Australian Army Journal 20, no. 1 (2024): 112; Department of Defence, Army Capability Assurance Processes (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005); Department of Defence, Defence Force Preparedness Management Systems (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2004).

[viii] Ball, Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia, p. 7.

[ix] Defence Strategic Review, p. 12.

[x] Nicole Brangwin and David Watt, The State of Australia’s Defence: A Quick Guide, Australian Parliamentary Library Research Paper Series (Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2022), p. 12.

[xi] Defence Strategic Review, p. 13.

[xii] National Defence Strategy, p. 6.

[xiii] Ball, Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia, p. 7.

[xvii] Defence Strategic Review, p. 58.

[xviii] Defence Efficiency Review, Future Directions for the Management of Australia’s Defence: Report of the Defence Efficiency Review (Canberra: Department of Defence, 1997), p. E-2.

[xix] Ball, Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia, p. 7.