- Home

- Library

- Volume 20 Number 3

- The Concept of Mobilisation and Australian Defence Policy since Vietnam

The Concept of Mobilisation and Australian Defence Policy since Vietnam

For the past five decades, Australian defence policy has focused on potential low-level threats from a small or middle power in its immediate region, and on the ability to sustain (relatively small) elements of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) on often quite lengthy operations overseas. While the latter certainly stressed parts of the force, throughout this time Australia could draw on discretion about its commitments,[1] the ADF’s overall capability edge over regional forces, and the deterrent value of the US alliance to limit escalation and the overall scale of conflicts it engaged in, or prepared for. Throughout this time, more substantial challenges were acknowledged as a future possibility that would only emerge with significant warning.

Today, much of this has changed. The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) focuses the ADF on the possibility of great power conflict in our immediate region, finding ‘that the ADF as currently constituted and equipped is not fully fit for purpose’.[2] In part, this is a judgement about the types of capabilities held in today’s ADF. In part, it is about the ability of the ADF as a whole to operate in major conflict, rather than generating smaller task groups. In part, it is also about the readiness and size of the ADF relative to the scale required for possible major conflict. It is therefore unsurprising that there is renewed interest in mobilisation, including in Australia’s own experiences from World War I, World War II and Cold War examples, and in the past and present approaches of international partners.

This article begins by arguing that while mobilisation is a national challenge, it can take very different forms and have very different purposes when mapped against force structure and preparedness outcomes. Hence, the term ‘mobilisation’ may obscure as much as elucidate practical implications, especially at the levels of force design and preparedness which are of particular relevance to Army. The second part reviews Australian policy of the last five decades in light of these different forms of mobilisation. The third part maps these considerations against current strategic challenges, followed by conclusions for Army as it considers the implications of mobilisation in the current era.

Endnotes

[1] As often expressed in the phrase ‘wars of choice’.

[2] Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 7.

The Encyclopedia Britannica defines ‘mobilisation’ as the:

organization of the armed forces of a nation for active military service in time of war or other national emergency. In its full scope, mobilization includes the organization of all resources of a nation for support of the military effort.[3]

‘Mobilisation’ thus has connotations of a nation and its armed forces moving from a peacetime to a wartime footing, and of raising forces for imminent, major war—of shifting resources from civilian to military uses. In addition, there is an important temporal aspect to mobilisation. ‘Mobilisation’ is contingent on, and a reaction to, a crisis or conflict; it implies a fast movement driven by urgent strategic need; while nonetheless also inevitably taking time.

Common Elements: Contingent Nature, Readiness-Size Trade-off and Civilian Resources

From a conceptual and planning perspective, it is useful to think about the process of mobilisation—in temporal as well as resource implications—as moving up a scale of readiness, whether that is at the level of a unit, Army, or nation as a whole. Given the demands of training, personnel movement and maintenance or renewal of equipment, military forces cannot be permanently kept at the highest levels of readiness. The same is true for nations, as military expenditure above a certain level comes at the cost of the economic dynamism and growth that ultimately sustains the long-term defence potential of a nation. Such a concern, for example, motivated the Eisenhower administration to reduce military expenditure even as the ‘Cold War’ was at some of its tensest points in the 1950s. Readiness costs, which means that there is a fundamental and inescapable trade-off in defence planning between readiness and force size.

In that sense, ‘mobilisation’ is about moving from the peacetime point of that trade-off—which will in general emphasise size over readiness—to a wartime point which increases readiness overall by drawing on new resources previously devoted to civilian use. As a policy and planning challenge, the key questions of mobilisation relate to the appropriate peacetime balance between readiness and scale to maximise the overall potential of the force after mobilisation; how to manage the strategic risk that arises from the reliance on mobilisation decisions being taken at the required time; and what practical preparations today may ease the future transition from peacetime to wartime posture.

The concept of a ‘real option’[4] is useful in this context: investments today that do not provide direct use but provide the opportunity for further investments at a later time, and that can be triggered once new information is available. In a military context, reserve units, capabilities ‘fitted-for-not-with’ certain systems, contracts placing civilian transport services on retainer, or spare industrial capabilities in, for example, munitions plants, are all examples of capability investment that are ‘real options’.[5] Hence, investment in ‘real options’ for mobilisation can also operate at different time scales—akin to the way that investments in readiness, in acquisition or in research and development are investments into capability across different time scales for the baseline force. Over short time scales, this might constitute investment in additional reserve units; over the very long term, as was Eisenhower’s argument, the best investment into the nation’s ability to mobilise may well be to reduce today’s defence expenditure burden on the economy.[6] In his seminal book Military Readiness, Richard Betts usefully distinguishes ‘operational readiness’ as the readiness of active duty forces; ‘structural readiness’ in the form of formed units (in the reserves); and ‘mobilisation readiness’ as the ability to convert civilian resources of personnel and industry into new military capacity.[7]

Whatever the time scale over which mobilisation is anticipated, however—whether days of tactical warning, or years of strategic warning—a force which maximises the benefits of mobilisation is one which, as a whole, is held at as low a readiness level as is still prudent for a given assumed length of warning time. The tension inherent in this balancing effort needs to be managed, as it cannot be eliminated.

Raising New Forces, Activating Reserves and Maximising Civilian Support to Operations

Shifting resources from civilian use to military use, the contingent nature in reaction to external threat, and the concept of ‘real options’ are key elements for understanding mobilisation in general. But within this broad conceptual envelope, it is useful to distinguish between three different types of mobilisation, which all have these general characteristics but which differ significantly in relation to the reaction time required to increase capability after warning, and the practical measures required for implementation.[8]

The first is mobilisation as the raising of new forces by drafting new personnel into the armed forces, and producing new equipment—emphasising ‘mobilisation readiness’ in Betts’ terminology. Australia’s raising of the 1st and 2nd Australian Imperial Force in World War I and World War II is a good example of this kind of mobilisation, which also was the focus of much interwar defence planning. Investments in training establishments, spare industrial capacity and raw material stocks are possible ‘real option’ investments that could support such mobilisation, as well as investment in long-lead items. Here, Army traditionally differs from other services—in particular Navy and, in recent decades, Air Force—insofar as the ‘long-lead item’ most relevant for land forces traditionally relates to the generation of trained and experienced personnel rather than equipment (or ‘platforms’).[9] Hence, historically, systems prepared for this type of mobilisation included ‘skeleton units’ of officers and senior non-commissioned officers who would be ready to receive and train enlisted personnel as part of the mobilisation process. As demonstrated by World War I, World War II and even today’s travails in Ukraine, the time required for mobilisation in this sense would be measured in months at best (e.g. for training new infantry), and years for many other capabilities (including scaling ammunition production). This kind of mobilisation requires ‘strategic warning’ of a growing threat, making political will (rather than tactical surprise) a key consideration.

The second type is mobilisation as the activation of reserves, which is a more relevant approach if warning is measured in days or weeks rather than years—or ‘structural readiness’ of formed units in Bett’s terminology. Most countries under persistent, direct land threat have standing armies that may be little more than a training and initial screening force, with the wartime army largely consisting of mobilised reserves—European Cold War militaries, South Korea and Israel being good examples. Rather than skeleton units, reserves in this case are formed units (if not always equipped to the latest standard, for largely financial reasons).[10]

If the activation of reserves is a key component of a country’s defence posture, the timing of that activation—and the length for which it can be sustained—become crucial questions for strategic as well as economic reasons, with far-reaching implications for crisis management and overall strategy. For example, calling up a large part of the working population can effectively stall the economy, making the need to end major wars quickly a key consideration in, for example, Israel. The act of mobilisation also becomes an important strategic development with implications for crisis management (as demonstrated to tragic effect in the outbreak of World War I in1914 and, through decisions to delay, in the Yom Kippur War of 1973). Further, the need to mobilise increases the challenge of managing the risk of strategic surprise. Both the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the Yom Kippur War led to significant attention in NATO on how to manage the risk of surprise attack through improved intelligence and force posture.[11] In the Cold War, NATO thus developed formal, graduated levels of warning that guided readiness and mobilisation, and which became important strategic signals in their own right.

Third, mobilisation can also refer to maximising civilian support to sustain military operations. In the Australian and US contexts of recent decades, this form of mobilisation is largely limited in approach to surging commercial support.[12] For countries that prepare to fight on their own territory, however, it can be far more extensive. It can entail the incorporation of military considerations into civilian infrastructure design, such as bridge loadings; creating military infrastructure as part of civilian networks, such as rail heads, telephone cables,[13] fuel pipelines, hospital surge wings, or even whole canals;[14] and drawing on pre-identified civilian equipment such as rolling stock, trucks, aircraft,[15] construction equipment, and even stocks of office supplies and bedding.[16] Again, European countries in the Cold War made significant use of this type of mobilisation, aided by significant state ownership of major utilities.

Maximising civilian support thus entails its own distinct preparations and investments. Insofar as a state will need to continually assure access to essential health, transportation and emergency services to the population, mobilisation efforts can operate in direct tension with the two previously discussed approaches. Therefore, it requires a national approach to workforce management of essential professions. To some extent, the practical steps required to maximise civilian support to military operations will require similar processes to those used for civil defence or resilience measures—one example being the incorporation of air raid shelters in public (and sometimes private) facilities, as occurs in South Korea, Israel and Finland. In addition to close interdepartmental liaison, maximising civilian support requires a broad geographic presence that, in the German Cold War example, took the form of army liaison commands and dedicated mixed civil/military maintenance squads stationed in every Kreis (county/shire).[17] It also requires legal and organisational structures to prepare for the timely requisition of civilian equipment, including trucks, facilities or aircraft, for military use.

All three of the above approaches are thus forms of mobilisation, as each trades readiness for scale by relying on the shift of civilian resources to military use in case of conflict. All three of them require significant investment—financial as well as organisational—in ‘real options’ to prepare for and enable mobilisation. But, as is evident from the discussion above, the kinds of investments required for raising new forces, for activating reserves and for maximising civilian support often have conflicting implications for specific elements of the mobilisation system—such as whether to establish military reserves as skeleton or fully formed units, or to increase or reallocate personnel from training units. Distinguishing between these different types of mobilisation therefore aids understanding of the operational benefits, strategic constraints and costs involved in mobilisation in a specific situation. And they are also areas where Australian policy of the last five decades has more useful history to offer—in practical or precautionary terms—than might be suggested by the absence of the term ‘mobilisation’ in many key documents.

Endnotes

[3]‘Mobilization’, Britannica, at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/mobilization (accessed 15 May 2024).

[4]Avinash K Dixit and Robert S Pindyck, Investment under Uncertainty (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[5]In civilian contexts, certain financial instruments but also oil exploration licences or the purchase of vacant land are such ‘real options’. T Copeland and V Antikarov, Real Options: A Practitioner’s Guide (New York: Texere, 2001); M Amran and N Kulatilaka, Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999).

[6] In 1952, US defence expenditure in the context of the Korean War was 13.9 per cent of GDP (SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, at: https://milex.sipri.org/sipri).

[7] RK Betts, Military Readiness (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1995), pp. 40-43.

[8]For example, what was effectively a mobilisation that focused on the activation of reserves in 1999 for East Timor saw many ADF training establishments denuded of personnel to round out operational forces. If it had been necessary to sustain this mobilisation for an extended period of time, the ability to raise new forces would have been significantly affected.

[9]While force expansion has not received much analytic attention in recent decades, one paper that sets out a useful parametric model after the Cold War is JA Dewar, SC Bankes and SJA Edwards, Expandability of the 21st Century Army (Santa Monica CA: RAND, 2000). One of its findings—the benefit of relatively large materiel holdings from Cold War times—would be unlikely to hold true today.

[10]For discussion of the role of mobilisation in Cold War defence planning in Europe, see for example RP Haffa, Rational Methods, Prudent Choices: Planning U.S. Forces (Washington DC: National Defense University Press, 1988); WP Mako, U.S. Ground Forces and the Defense of Central Europe (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1983); J Simon (ed.), NATO–Warsaw Pact Force Mobilization (Washington DC: National Defense University, 1988); and Barry R Posen, ‘Is NATO Decisively Outnumbered?’, International Security 12, no. 4 (1988), pp. 186–202.

[11]The classic text on the implications of surprise attack for defence planning is RK Betts, Surprise Attack: Lessons for Defense Planning (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1982).

[12]Of note is that in the United States, the Defense Production Act gives government the ability to direct industry to give priority to military orders over civilian ones.

[13]One of the authors has memories, as a conscript in the 1990s, of accessing the regular German copper phone network via concealed junction boxes, dispersed throughout the landscape in hedges among agricultural fields, to establish communications for battalion HQ.

[14]The Elbeseitenkanal in Northern Germany, running 115 km due south from the Elbe along the former inner-German border, was partly built to provide a major tank obstacle on the North German plain; its shores can be forded by tanks from west to east but not the other way around.

[15]E.g. the US Civil Reserve Air Fleet (https://www.amc.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/144025/civil-reserve-air-fleet/).

[16]An anecdotal example, according to a family member of one of the authors, illustrates the extent this can reach: a medical reserve unit had almost no organic equipment but could, with requisition orders for specific trucks and buses and drawing on timber, typewriters, and bedding held on stock for the purpose by local stores, equip railway cars and fishing boats with makeshift stretchers to create an evacuation route from Schleswig-Holstein to Britain (and did practise doing so).

[17]Tasks of these units included working with counties to incorporate military considerations in infrastructure (such as bridge loadings, prepared explosive chambers, or integrated concrete tank barriers), and maintaining buried caches of supplies, including explosives, for demolition work.

For most of the past 50 years, Australia’s defence policies were based on the strategic judgement that while lesser contingencies were credible in the shorter term, higher levels of contingency would only arise in the longer term, after an extended period of strategic deterioration.[18] A strategic warning period of 10 to 15 years was envisaged. Intelligence analysis would provide this warning, leading to a timely response by the government through the expansion of the ADF. These were the tenets on which Defence developed the concepts of ‘core force’ and ‘expansion base’. Because the 1987 White Paper clarified that priority should be given to shorter-warning, low-level conflict, the importance of reserve units that could be activated to fulfil pre-assigned roles in specific scenarios increased, as did the reliance on the ‘national support base’.

Core Force and Expansion Base in the 1970s and 1980s

By the 1970s, a key tenet of policy was that the time it would take to develop ADF capabilities from a very low or non-existent base would be longer than the time scales over which it was possible to make confident intelligence assessments about the emergence of serious threats to Australia. From such considerations emerged the principle that the ADF should be able to handle credible lesser contingencies that could emerge at short notice, while maintaining an expansion base of sufficient capacity to allow timely expansion in the event of strategic deterioration. An advantage of this approach was that other departments within the machinery of government accepted it as a convincing framework within which Defence could argue for levels of funding. Much of this approach was set out in the 1976 Defence White Paper.[19]

Army’s interpretation of the ‘core force’ concept meant that each of the three regular brigades (or ‘task forces’ at the time) of 1st Division should have a specialised focus to maintain different expertise: 3rd Task Force in Townsville was the ‘Operational Deployment Force’ for short-warning contingencies and tropical operations (and held at high readiness); 6th Task Force in Brisbane maintained skills in open-country and built-up area combat as well as amphibious operations; and 1st Task Force focused on mechanised operations.[20] Before the 1987 Defence White Paper, Army’s overall force structure concept was set down in the Army Development Guide, which envisaged that, after strategic warning, Army would grow to an ‘Objective Force’ of five divisions.[21]

The late 1970s and early 1980s were not the first time Australia had included mobilisation in its defence policies; nor was Australia the first country to do so. But unlike the British Commonwealth and the United States, which during the interwar years could base their mobilisation planning on prospective threats from Germany and Japan, Australia after the Vietnam War did not have a clear future adversary to plan against. This was the whole point of the core force concept.[22] For example, in 1981 the Department of Defence explained:

The core force is not a static entity maintained against the day when warning of a particular threat is declared to have been received. Rather, the expansion base provided by the force-in-being is continually being developed in response to changing circumstances including both strategic and technological. The expansion capacity of the Defence Force will depend on many factors such as the extent of the developing threat, the civil resources that are mobilised and directed to its development and the extent of support in the community. Numerous study treatments have demonstrated the futility of relying on simplistic analysis techniques drawn from peace-time derived data for assessment of expansion capacity.[23]

George Cawsey (then First Assistant Secretary Force Development and Analysis, and later Deputy Secretary), had earlier commented:

The [core force] notion is essentially simple; in a sense it is almost a null concept. Essentially all forces anywhere are core forces which can be expanded, contracted or changed in concept to meet a variation of the strategic conception either in a time of peace, threat of war or time of war. Core force is just another pair of portmanteau words which can if necessary be defined accurately, but I think … it is unnecessary to do so.[24]

The challenge of mobilisation planning also attracted academic attention. Suggestions for giving it a clearer focus took two complementary approaches: to more clearly define specific scenarios as a focus for planning,[25] and to integrate mobilisation into a wider concept of deterrence by denial.[26] JO Langtry and Desmond Ball developed these approaches in more detail,[27] building on ideas on how to implement conventional deterrence in the Australian context.[28] Central to their arguments was the use by Australia of:

specific capabilities that will cause a potential aggressor to respond disproportionately in terms of the cost in one or all of money, time, materiel, and/or manpower in order to gain the advantage.[29]

Notably, the ideas developed by Ball and his other colleagues were focused on future rather than present threats, and hence closer to the concept of dissuasion (of the emergence of new enemy capabilities)[30] rather than deterrence in a more limited sense (i.e. of hostile enemy actions themselves). Robert O’Neill made this distinction at the time, when he wrote that:

we are concerned with deterrence, but in most cases it is not deterrence of the use of forces which exist but deterrence of the development of forces which could project substantial combat power across the great distances which separate Australia from any potential enemy nation.[31]

Potential enemies would thus be forced to undertake military build-ups of a kind that would provide unambiguous warning, a longer reaction time, and more information about the enemy challenge.[32] This would create the conditions for Australian forces to be built up in an appropriate, more balanced fashion.[33]

While developing the concept of mobilisation was thus a subject of academic debate, in practice force expansion received little analytical or policy attention. This was in part due to the assessment within Defence that the need for serious expansion would be too far into the future to command priority. There were, nevertheless, some attempts to address mobilisation. These included efforts to rewrite and update the Commonwealth War Book (a detailed guide to national mobilisation), an activity that was abandoned before completion.[34] There were also broad-based conceptual studies of the principles of force expansion and, for example, a study of Australia’s future needs for air defence. Occasionally force expansion was raised in the context of new major capital equipment projects, but in practice this consideration remained at the margins.[35] None of this work had a lasting effect, except perhaps to reinforce the view that there was little priority for more extensive analysis.

Reserves and National Support Base after the 1987 White Paper

Ultimately, disagreements between the Secretary and the Chief of the Defence Force on priorities for the development of the ADF led the Minister for Defence in 1985 to commission an independent review of Australia’s defence capabilities. This review, conducted by Paul Dibb, was critical of Army’s interpretation of strategic guidance, and reset the framework for the Army’s development, including for force expansion.[36] In effect, the subsequent 1987 Defence White Paper reinforced the priority of low-intensity, short-warning conflict for Australian defence planning, including for the Army. In consequence, the activation of fully formed reserves, and preparations to draw on the national support base for operations, took precedence over force expansion.

This meant that the focus of reserves shifted from ‘mobilisation readiness’ of skeleton units to ‘structural readiness’ as a follow-on force. Reserve forces would be activated in case of regional conflict, and would be used for the security of ADF bases in the north of Australia, including through the regional surveillance units. In this framework, the size of the Army Reserve was thus directly related to the installations and settlements that the government would wish to protect in conflict in the north, and less related to being able to grow into a hypothetical future force. The Dibb Review also recommended that reserve units in peacetime be allocated their wartime roles,[37] a call that is repeated in the DSR.[38] One assessment is that the Dibb Review ‘generated considerable angst for the Army’ but that it also ‘left the Army and the ADF well placed to move forward with the development of more robust capabilities for offshore deployments later on’.[39]

The 1987 White Paper announced legislation to enable a more flexible call-out of reserves, and closer integration of regulars and reserves both in the 1st Division and in Logistic Support Force.[40] Other developments, especially since the 2000 White Paper, included a greater focus on the use of the reserves to round out units of the regular Army, including at times of high operational demand.

In 1991, the ‘Ready Reserve’ was introduced as a (short-lived) means to broaden recruitment, save costs and better align readiness options between the regular force and conventional reserves. At the time, Defence stated that ‘Ready Reserve forces may become a widely used means of mapping an expanded force structure in the event of changed strategic circumstances’.[41] A later review found that Ready Reserve units cost about 60 to 65 per cent of equivalent regular units. Army focused most of its use of the scheme on infantry, as developing reservists’ skills in more technical branches proved more difficult. One challenge of the scheme was that reservists were not geographically concentrated, which made it harder to train at unit level.[42] Later decisions, especially since the 2000 White Paper, placed greater focus on the use of the reserves to round out units of the regular Army, including at times of high operational demand.

The challenges that arose in responding to a short-warning, low-level conflict in Australia’s north made it both necessary and possible to rely on civil support to ADF operations in and movement into that region. Likewise, the 1990 report The Defence Force and the Community[43] by Alan Wrigley (a former Defence Deputy Secretary) proposed greater use by the ADF of civil infrastructure and industry (and greater use of the reserves). As part of the Commercial Support Program that arose from the 1990 Wrigley Review and 1991 Force Structure Review, Defence’s logistics activities were separated into those deemed ‘core’ and those deemed ‘non-core’. The latter were market tested and, if the costings suggested it, the activities thus identified were outsourced. Likewise, the 1997 Defence Efficiency Review (DER) found that considerable savings could be made through a combination of integrating support services, civilianisation, and further market testing and outsourcing. Logistics concepts increasingly reflected assumptions about the broad use of commercial support for ADF operations. This development that was strengthened by the DER, which led to the establishment of the ‘National Support Division’ in ADF Headquarters—a term and function that the DSR recommended be resurrected.[44] David Beaumont defines the ‘national support base’ as:

the sum of organic Defence capability (and not just capability resident in the military, but also the Department), support from coalition forces and host nations, and support that is provided by national industry and infrastructure.

It is the available strategic logistics capability, including that which is inorganic to the military, that, properly empowered, acts as a ‘shock absorber’ when a nation encounters a military threat.[45]

But as become apparent in the lead-up to the 1999 East Timor operation, the assumption that civil support would be available to the ADF in many ways remained just that, as organic logistic capability was cut but not replaced by sufficient practical preparations to implement the new approach. In practice, implementation of the concept of the ‘national support base’ focused less on developing new mechanisms to increase civilian support to Defence in wartime, and more on the shift of Defence organic logistics capability into the civilian economy. In doing so, Defence lost sight of the DER’s finding that ‘[a] fundamental element of defence policy for industry should be to use the widest possible range of industrial support in peace because that will be necessary in war’ (emphasis added).[46] In the Australian context, the challenges posed by this aspect of mobilisation are amplified by the structure of the domestic defence industry.

Sovereign Defence Industry as a Fundamental Input to Capability

Industrial capability and capacity to provide systems and hardware for defence use is a fundamental requirement for raising new forces, for the activation of reserves, and for maximising civilian support. The 1987 Defence White Paper stated that ‘wherever possible Australian firms will be prime contractors on major projects and Australian industry involvement will be a major factor in selection new equipment’, as the ‘benefits to industry in peace will be returned as increased capability in time of hostility’.[47] Government intentions at this time were to explicitly build self-reliance and, implicitly, to facilitate mobilisation should the circumstances require it.

Structural developments in the domestic defence industry since the 1980s have overturned that ambition, resulting in a sector that is skewed towards the participation of large offshore primes and their local subsidiaries established to support specific programs. The reorientation of the Australian defence industry commenced with the partial privatisation of Australian Defence Industries (ADI) in 1999 and was reinforced through the Kinnaird Review in 2003. The Kinnaird Review recommended that at least one off-the-shelf option to be included in all capability business cases.[48] Government did not object to the sale of the remaining Australian component of ADI to French interests in 2006, and the sale of Tenix Defence to British interests in 2008. Subsequently the 2008 Mortimer Review reinforced the primacy of off-the-shelf solutions as the basis for force structure capability development.[49] The result has been the hollowing-out of more enduring domestic capability and capacity, a situation which was mirrored within the broader industrial base with the demise of Australian car manufacturing in the 2010s.

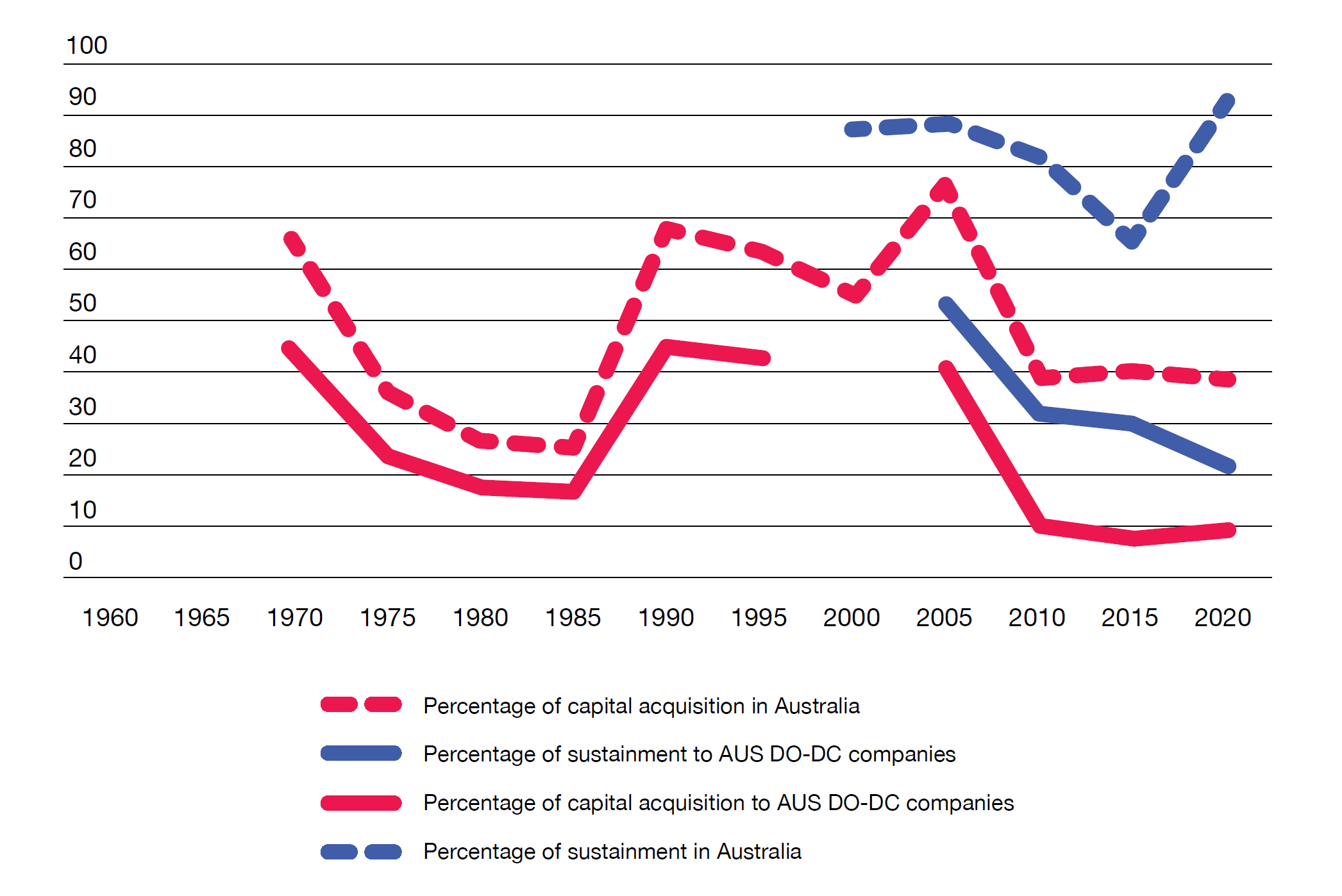

Figure 1: Percentage of acquisition and sustainment contracts placed with Australian owned and controlled companies between 1970 and 2020[50]

The consequences of this restructuring of the local industry were twofold—each of which reinforced the other on a cyclical basis and progressively decreased national capacity while increasing the challenges for any future mobilisation activity. Specifically, sale of the two largest Australian defence companies significantly reduced both the capability and the capacity of indigenous entities to develop and deliver defence systems and hardware. Meanwhile, the involvement of foreign suppliers, including their domestic subsidiaries, inevitably increased. The implementation of the recommendations of the Kinnaird and Mortimer reports made off-the-shelf offerings the default solutions for defence capability. This development reduced the potential for domestic companies to develop and supply product, and to contribute to the Australian force structure from indigenous sources. Australian companies were therefore demoted to the status of, at best, subcontractors to the foreign primes. The results can be seen in Figure 1 with the reduction of acquisition and sustainment activities contracted to Australian domestically operating, domestically controlled (DO-DC) companies by the Department of Defence, and reduction in domestic capital acquisition overall.

Recognising that certain military capabilities are more important for operational success than others, successive Australian governments have attempted to ensure that related industrial capabilities are maintained in country. In 2007 the Defence Industry Policy Statement (DIPS) highlighted ‘Priority Local Industry Capabilities’ as being capabilities ‘that confer an essential security and strategic advantage by resident in country’.[51] This theme was continued in the 2010 DIPS in the description of ‘Priority Industry Capabilities’ as ‘those industry capabilities which would confer an essential strategic advantage by being resident within Australia and which, if not available, would significantly undermine defence self-reliance and ADF operational capability’.[52] Subsequent policy statements continued the intent for, in 2018, ‘Sovereign Industry Capability Priorities’ for local industry capabilities that ‘are operationally critical to the Defence mission’[53] and, in 2024, the more nebulous ‘Sovereign Industry Development Priorities’ as ‘industrial capabilities [Defence] needs to deploy a defence capability if, when and how the Government directs’.[54]

One other development was the categorisation of industry as a ‘Fundamental Input to Capability’[55] (FIC) in the 2016 DIPS. This initiative was expected to ‘drive more formal consideration of industry impacts through the early stages of the capability life cycle’,[56] but how this was to be achieved was never defined. Consequently, the way in which industry might be developed to support defence priorities was not progressed and the policy did not address weaknesses in the structure of the domestic defence industry. This overall lack of direction vis-à-vis the defence industry is more recently amplified in the 2024 Defence Industry Development Strategy in that neither the role nor the contribution of industry as a FIC rates a single explicit mention.

For Army, the industrial challenges with respect to mobilisation have thus been ill defined, and despite decades of defence industry policy, the ability of the domestic industry to surge is limited. Recent efforts to maximise ‘Australian Industry Content’ and to spread the economic benefits across the country (as represented in decisions associated with Army vehicle acquisitions) has seen Thales, Rheinmetall and Hanwha establish manufacturing facilities in Australia.[57] However, each is sustained by only one or two programs, and none have any long-term commercial certainty. This situation is exacerbated by the loss of the domestic automotive industry, the cessation of complementary commercial vehicles activities, and the reduction in relevant skills and capacity.

Endnotes

[18]Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, Australia’s Fraser government was concerned that this action could well presage further Soviet expansion, through Pakistan, to reach the Indian Ocean. The government increased the defence budget of that year and instructed Defence to plan on significant further annual increases over the forward five-year program. Major expansion of the Army Reserve was envisaged. In the event, little of this happened, as the federal budget came under pressure and it became apparent that Australia’s initial response had been an overreaction, and that the Soviet Union was becoming bogged down in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, there had been sufficient confidence in the level of future funding for the government to make major commitments to significant air and maritime capabilities, such as the F/A-18 new tactical fighter aircraft.

[19]Department of Defence, Australian Defence (Canberra, 1976).

[20]Jeffrey Grey, The Australian Army, Australian Centenary History of Defence, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 234–235.

[21]On the challenges of Army to relate its force design to policy guidance in the 1970s and 1980s, see David Connery (ed.), The Battles Before: Case Studies of Australian Army Leadership after the Vietnam War, Australian Military History Series No. 3 (Canberra: Army History Unit, 2016), pp. 1–25.

[22]See Stephan Frühling, Defence Planning and Uncertainty (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014), pp. 67–89.

Department of Defence in Official Hansard Report, 18 March 1981, p. 1612, quoted in Ray Sunderland, Australia’s Defence Forces—Ready or Not?, Working Paper No. 94 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1985), pp. 6–7.

[24]Testimony of GF Cawsey, First Assistant Secretary, Force Development & Analysis Division, Department of Defence, in official Hansard Report of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs & Defence, Inquiry into Australia’s defence procurement programs and procedures, 9 November 1978, p. 1070, quoted in JO Langtry and Desmond Ball, Australia’s Strategic Situation and its Implications for Australian Industry, Reference Paper No. 38 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1980), p. 10.

[25]Ross Babbage, Rethinking Australia’s Defence (St Lucia: University Press of Queensland, 1980), esp. pp. 275–294; Ray Sunderland, ‘Problems in Australian Defence Planning’, Canberra Paper No. 36 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1986), esp. pp. 67–82; Ray Sunderland, Selecting Long-Term Force Structure Objectives, Working Paper No. 95 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1985).

[26]See Langtry and Ball’s discussion of the relationship between deterrence and ‘war-fighting’, itself based on distinctions en vogue at the time among American theorists of nuclear strategy. JO Langtry and Desmond Ball, Controlling Australia’s Threat Environment (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1979), pp. 9–21.

[27]Langtry and Ball, Controlling Australia’s Threat Environment. Their ideas were endorsed by both the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence (Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence, Australian Defence Force—Its Structure and Capabilities (Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 1984), p. 83) and the Labor Party (Desmond Ball, ‘Labor’s Policy of Self-Reliance and National Defence: A National Effort for a National Defence’, in John Reeves and Kelvin Thomson (eds), Policies and Programs for the Labor Government (Blackburn: Dove Communications, 1983), pp. 113–131), but the concept was incompatible with the growing emphasis placed on short warning time, low-level contingencies in Australian defence planning and thus did not become highly influential in practice.

[28]For a good overview on that discussion, see Michael Evans, Conventional Deterrence in the Australian Context, Working Paper No. 103 (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 1999), esp. pp. 18–28.

[29]Langtry and Ball, Controlling Australia’s Threat Environment, p. 22.

[30]Richard L Kugler, ‘Dissuasion as a Strategic Concept’, Strategic Forum 196 (2002); Jonathan Hagood, ‘Dissuading Nuclear Adversaries: The Strategic Concept of Dissuasion and the US Nuclear Arsenal’, Comparative Strategy 24, no. 2 (2005), pp. 173–184.

[31]Robert O’Neill, The Structure of Australia’s Defence Force, Working Paper No. 10 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1979), p. 8.

[32]Desmond Ball and JO Langtry. ‘Development of Australia’s Defence Force Structure: An Alternative Approach’, Pacific Defence Reporter 9, no. 3 (1979), pp. 7–16.

[33]Langtry and Ball, Controlling Australia’s Threat Environment, p. 23.

[34]The Commonwealth War Book provided a summary of important actions to be taken by government departments in the event of a need to put the whole nation on a war footing—that is to say, in a situation of national crisis where there was a need for policy and economic coordination and industrial mobilisation. A copy of the 1956 War Book is available, including in digital form, at the National Library of Australia (Bib ID 1182487) and at: https://seapower.navy.gov.au/media-room/publications/cwealth-war-book.

[35]One of the authors recalls, for example, the debate about Army’s proposal for trucks, tractors and semi-trailers. In brief, the Defence policy position was that, in contingencies, the ADF would necessarily rely heavily on the civil infrastructure, including the transport industry. It was appropriate, therefore, to exercise this reliance in peacetime.

[36]Paul Dibb, Review of Australia’s Defence Capabilities (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1986). Page 84 states: ‘This Review has substantial reservations about the conceptual framework of the Army Development Guide’.

[37]Ibid., pp. 80, 85–86, 154; Department of Defence, The Defence of Australia (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1987), p. 55.

[38]Defence Strategic Review, p. 58, para. 8.30.

[39]John Blaxland, The Australian Army from Whitlam to Howard (Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 59. This book provides a valuable perspective from an Army point of view of much of the period discussed in this paper.

[40]The Defence of Australia, pp. 59–60.

[41]Department of Defence, Ready Reserve Program 1991 (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1991), p. 12.

[42]For an extensive discussion of the practical experience of the scheme, see Lt Gen John Coates and Hugh Smith, Review of the Ready Reserve Scheme (Canberra: UNSW Canberra, 1995).

[43][43] Alan Wrigley, The Defence Force and the Community: A Partnership in Australia’s Defence (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1990).

[44]Defence Strategic Review, p. 82.

[45]David Beaumont, ‘The Strategic Shift and Rethinking the National Support Base’, Defense.info, 25 May 2019, at: https://defense.info/re-shaping-defense-security/2019/05/the-strategic-shift-and-rethinking-the-national-support-base/ (accessed 24 April 2024).

[46]Department of Defence, Defence Efficiency Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1997), p. E-5.

[47]The Defence of Australia, p. x.

[48]Department of Defence, Defence Procurement Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2003).

[49]Department of Defence, Going to the Next Level: The Report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008).

[50]Graeme Dunk, ‘Operational and Defence Industry Sovereignty’, PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2024. The data for the construction of this graph has come from a wide variety of sources, including Defence Annual Reports, Defence White Papers, and www.austender.gov.au. Data for the period 1970 to 1995 for acquisition contracts awarded to Australian-controlled companies has been generated by using the involvement of Australian companies in Collins-class submarine AII as a baseline.

[51]Department of Defence, Defence and Industry Policy Statement (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2007), p. 4.

[52]Department of Defence, Building Defence Capability: A Policy for a Smarter and More Agile Defence Industry Base (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2010), para. 4.9.

[53]Department of Defence, Defence Industry Capability Plan (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2018), p. 8.

[54]Department of Defence, Defence Industry Development Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 17.

[55]The full range of fundamental inputs to capability are personnel, organisation, collective training, major systems, supplies, facilities and training areas, support, command and management, and industry.

[56]Department of Defence, Defence Industry Policy Statement (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2016), p. 19.

[57]Thales manufactures Bushmaster and Hawkei vehicles in Bendigo, Victoria. Rheinmetall manufactures the Boxer Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle (CRV) at Redbank, Queensland. Hanwha will manufacture the Redback Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV) at Avalon, Victoria.

Today Australia’s strategic situation is significantly more challenging than when Australian policy last engaged with the different approaches to mobilisation discussed above. China’s military capabilities now give it the potential to conduct and sustain sophisticated operations against Australia’s interests, were it to develop the motive and intent to do so. Warning time must now reflect the time scales within which motive and intent can change, which are much shorter than the time needed for an adversary to develop capabilities to be used directly against Australia where they do not already exist. This leads to the conclusion that warning times now would be much shorter than those assumed in the era of ‘core force’ and ‘expansion base’. In addition, contingencies even in the shorter term could be conducted at high levels of technological sophistication and lethality. Further, assessment of motive and intent is inherently difficult and subject to ambiguity, as recently demonstrated by the Russian build-up of forces before invading Ukraine in February 2022. Although some degree of political warning could be anticipated, an obvious warning threshold would likely again be absent, which could result in strategic surprise. Yet the consequences of getting it wrong would be severe, much more so than in the past.

Mobilisation Planning in the National Defence Strategy

Based on the considerations outlined above, there is a need for the Defence, the ADF and Army to have the capacity to surge and to sustain the higher rates of effort that short-warning contingencies would require. They also need to be able to operate at a scale commensurate with the size of adversary capabilities that could be deployed against Australia. This requirement in turn implies that the spectrum of readiness across the different elements of the ADF should be different from that of the past. At the same time, with the growth of Chinese forces and defence industrial capacity, the warning time for a major threat has become shorter than in earlier decades. This situation amplifies the importance of formed reserve units and civilian support as the key pillars of future mobilisation efforts. It requires procedures to be developed and tested, well in advance, to ensure that such surge, if required, would be successful.

The contingencies that comprise the defence planning base are not publicly known, but the DSR and the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) imply that they consist of a set of different levels of operation, with less demanding campaigns forming the basis for the shorter term and more serious contingencies beyond that.[58] We might conclude too that the planning base recognises the likelihood that China’s capacity for military action will continue to grow.

There is, however, little available to the public about what the new strategic environment and the strategy of denial mean in practice for readiness, sustainability, surge capacity and force expansion.[59] The NDS says only that the strategy of denial requires ‘appropriate levels of preparedness’,[60] and that the reform agenda encompasses ‘force posture, preparedness and employment reform to ensure Defence’s disposition, size, strength and readiness enables the Strategy of Denial’.[61] The 2024 Integrated Investment Program (IIP) elaborates a little on this:

ADF reservists will continue to form an essential component of the Defence workforce, representing thousands of personnel fully trained and ready to serve. Coming from all walks of life, reservists will continue to contribute their unique combination of skills, knowledge and experience to Defence’s mission.[62]

Specifically on the topic of the Army Reserve, the IIP says:

Investment in the Army Reserve will deliver enhanced domestic security and response capabilities, which will strengthen its ability to provide security for northern bases and critical infrastructure and help it prepare for potential future contingencies.[63]

The investment program includes between $200 million and $300 million over the 10-year period of 2024–25 to 2033–34 for recapitalisation of the Army Reserve.[64]

In brief, much depends on the contingencies in the planning base. These will determine not only the most appropriate force structure and its profile with respect to readiness and sustainability, but also the capacity of industry to increase its support to the ADF, especially as regards ammunition and other consumables. The latter raises questions of risk management: where should Defence strike the balance between stockpiles of consumables, stocks of components or raw materials, an indigenous capacity to surge production, reliance on overseas suppliers, and costs?[65]

Mobilisation in Possible Contingencies

A key consideration that arises from both international and Australian examples of mobilisation discussed so far is that a close link to operational planning is crucial for effective mobilisation planning and the management of the trade-offs that reliance on mobilisation entails. For the purpose of this article, a broad taxonomy of contingencies comprises the separate needs to protect and promote Australia’s interests in the event of maritime coercion or limited (e.g. special forces or air) attack on Australia’s coastline or overseas territories, and to conduct littoral operations in the South Pacific. Both classes of contingencies could occur at a variety of levels of intensity, and would in part require similar capabilities. Such contingencies would, however, differ notably in the risk to deployed forces and the availability of civilian support.

Already the need to counter maritime coercion and to provide for coastal defence would require protection of the bases from which Australian maritime power can be projected, and of other critical infrastructure across the country. The use of the reserves for this task has become well accepted, as advocated for example in the Dibb Review[66] and as emphasised in the DSR.[67] In terms of the three classes of mobilisation discussed earlier in this article, this kind of response falls into the category of activation of reserves. That is, formed units, already familiar with and trained in their responsibilities and areas of operation, would take up their duties. One should expect that the levels of readiness now required for such units would be higher than in earlier decades, and that the geographic expanse that will require active protection now also includes critical infrastructure in the south-east and south-west of the continent.

It appears that Defence planning is based on this approach and also includes the use of reserve units in an enabling capacity, such as in the provision of enhanced logistic support. Forward-deployed forces within Australia would also increase the demands for civilian support. This requirement too needs to be planned for, as has been recognised over many years (although whether the contemporary focus on this is sufficient is not clear). This set of needs invites the observation that special reserve units could be formed within private companies—for example the trucking industry or civilian airfield operators—to be activated when contingencies required it.

Equipment holdings for reserve units would need to be more complete, with much less sharing of equipment between units, especially for specialist equipment such as secure communications that could not be quickly acquired from industry. Looking to Cold War examples of other countries, it is worth further examining the question as to what extent the equipment of such units might be drawn from civilian equipment pre-identified for requisition in wartime. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a view on whether the extra $20 million to $30 million per year for recapitalisation of the Army Reserve over the forward 10-year period would be sufficient for this capability. In reality, this figure could well fall short of what would be required if Army prioritised post-mobilisation size over readiness of the regular force.

A second significant role for land forces will be littoral operations in the South Pacific, especially to secure lines of communication to Australia’s north and east and to forestall or respond to possible hostile lodgements. Australia’s regular forces would likely have the prime responsibility for such operations, given the need for high levels of training for joint, combined operations that would be involved; and because the difficulty of manoeuvre in the presence of hostile forces would likely mean that there would be a strong incentive to move forces early in a conflict. Nevertheless, irrespective of the military logic, the political and diplomatic difficulties and uncertainties of deploying to sovereign states could well lead to reluctance to make early decisions on such deployments.

Because the island states in the South Pacific have limited civil resources upon which deployed Australian and allied forces could draw, there may be a case for planning to use specialist reserve units to provide services (e.g. medical support) that ADF operations in Australia itself could draw on from civilian sources. This situation reinforces the conclusion that the specialisation and structuring of reserve units for specific operational tasks, in specific geographic areas and in support of specific regular forces will be an increasingly important characteristic of overall force design.

It is also possible that, in response to maritime coercion, Australian forces would seek to operate out of forward bases in South-East Asian countries to Australia’s north. In this context, there could well be a role for the Army in contributing to the security of such bases, but the logistic capability of host nations there is significantly larger than that in the South-West Pacific. Both the deployment of Australian forces and their contribution to host-nation protection would occur only if the host government agreed. The degree of speculation associated with such possibilities does not allow useful conclusions about mobilisation, other than to observe that, if there were such deployments, they would be yet another drain on resources. This is because they would require the same capabilities as protection of bases and coastal defence in Australia itself [68]—a realisation that further emphasises the need to maximise the size of the total post-mobilisation force.

Of note, conflict in Taiwan would be a serious development, and Australia would likely feel obligated to contribute to operations in support of those under attack. However, rather than constituting additional tasks for land forces, such contributions would likely be in the hosting and support of US long-range strike forces in Australia, and during maritime operations (including those mentioned above), to secure the continent and its lines of communication.[69]

Beyond this, there is also the question of the extent to which the planning basis should include defence of the Australian homeland against major assault.[70] The view expressed in the 2023 DSR that such a contingency is remote is broadly consistent with the policy judgements of the ‘core force’ and ‘expansion base’ era. This remoteness continues to suggest, therefore, that capabilities developed or maintained for such a strategic deterioration should be at a minimal level and command low priority. The increased need for large-scale activation of the reserves suggested by the contingencies discussed above raises questions about whether the reserves could continue to fulfil the major role of expansion base they have played in the past. A particular conclusion is that, while the situation should be subject to periodic review, there is a stronger case for focusing preparations for force expansion on the demands of personnel replacement and reconstitution in response to (possibly protracted) short-warning conflict, rather than on massive expansion of the force as a whole.

Endnotes

[58]For example, the DSR sets out three distinct time periods for defence planning: 2023–2025, 2026–2030, and 2031 and beyond (p. 25). It is important to recognise that the contingencies outlined above would be quite different from those of the ‘Core Force’ and ‘Expansion Base’ era even though there are some superficial similarities. There would be the risk of high levels of lethal force even in the shorter term, and the warning times for more significant combat would not be the 10-plus years of earlier policies.

[59]The concept of ‘Strategy of Denial’ has emerged from analysis supporting defence policy since the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, as well as from Australian National University academic work: see Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith, Deterrence through Denial (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2021). This paper was the subject of a meeting between the authors and a Defence team led by the Chief of the Defence Force later in 2021.

[60]Department of Defence, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 24.

[61] Ibid., p. 71.

[62]Department of Defence, Integrated Investment Program (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 17.

[63] Ibid., p. 55.

[64] Ibid., p. 59.

[65]Note that the DSR calls for ‘enhanced sovereign defence industry capacity in key areas’ (p. 32). Also see pp. 38 and 45, and pp. 81–82 for ‘Accelerated Preparedness’.

[66]Dibb, Review of Australia’s Defence Capabilities, pp. 78–86, 150–159.

[67]Defence Strategic Review, p. 58. Paragraph 8.30 states that ‘Enhanced domestic security and response Army Reserve brigades will be required to provide area security to the northern base network and other critical infrastructure, as well as providing an expansion base and follow-on forces’.

[68]On force structure implications of possible Army forward presence, see Andrew Carr and Stephan Frühling, Forward Presence for Deterrence: Implications for the Australian Army, Occasional Paper No. 15 (Canberra: Australian Army Research Centre, 2023).

[69]In terms of a large-scale and primarily land conflict in the Indo-Pacific that might involve Australia, a North Korean attack on South Korea is the only credible contingency. However, for the most part, since the end of the war in Vietnam, Australian governments have shown little appetite for sending ground forces off shore for high-intensity conflict. Notwithstanding the ambiguity of the 2016 Defence White Paper on defence priorities (see for example Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2016), p. 71), policy in practice is well summarised in the 2000 Defence White Paper: ‘We have, however, decided against the development of heavy armoured forces suitable for contributions to coalition forces in high intensity conflicts’ (Department of Defence, Defence 2000: Our Future Defence Force (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2000), p. 79). See also Dibb and Brabin-Smith, Deterrence through Denial, pp. 14 and 15, for a discussion of Taiwanese and Korean contingencies.

[70]The DSR states on p. 25: ‘While there is at present only a remote possibility of any power contemplating an invasion of our continent, the threat of the use of military force or coercion against Australia does not require invasion’.

Applying the mobilisation categories of activation of reserves, civilian support, and force expansion to contingencies derived from consideration of Australia’s new strategic circumstances thus brings no surprises in the principal observation: a prudent approach to contingency planning means giving an increased emphasis to activation of reserve forces and to planning for civilian support to deployed forces. If further and more detailed analysis shows that today’s Army Reserve would not be sufficient in number to undertake the responsibilities given to them, consideration should be given to raising more reserve units now. This leads to the conclusion that, depending on the desired size of the post-mobilised force, there is likely to be a strong argument to shift resources from the regular force to the reserves.

However, it is important to recognise that the move to a defence posture and strategy that relies heavily on mobilisation involves issues that go beyond just the force structure. It is far from clear that Defence’s present governance arrangements are adequate, either in general or for the specific issue of mobilisation.[71] Any discussion of how to prepare for mobilisation would do well to keep in mind the first recommendation of the DER of 1997: ‘The Defence Organisation should be organised for war and adapted for peace’.[72] The deterioration in Australia’s strategic circumstances since this observation was first made makes the observation even more relevant today.

As the threat of war would bring with it a need for mobilisation, the defence organisation needs to think of itself more as a mobilisation organisation. As far back as 1980, Desmond Ball wrote:

Departmental thinking today is dominated by the concerns of peacetime management. Insofar as the military considers the requirements of mobilisation and possible war-fighting, such consideration is almost entirely in terms of hardware and of equipment acquisition lead-times. … [T]here is evidently an assumption prevalent within the Australian Defence Force to the effect that organisation, command, and staffing, personnel and infrastructure arrangements are either zero or at least very short lead-time items.[73]

Australia’s strategic environment, and the focus of the defence organisation on it, have changed significantly since the greater urgency instilled in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, and it would be good if the departmental mindset outlined by Ball were no longer the case. More likely, progress to date will have been uneven, and some of the trends that need to be reversed are very longstanding. For example, the public consultation process of the 2016 White Paper highlighted that decades of ‘rationalisation’ of reserve bases had led to a growing gap between the Australian population and the ADF.[74] An Army that relies on mobilisation of any of the three types discussed herein will have to reverse that trend.

For Australia, the strongest historical connotation of ‘mobilisation’ is force expansion—an association that dominated Army force structure planning as recently as the mid-1980s. However, the analysis above suggests that this should not remain the strongest focus in contemporary circumstances. Major power conflict involving Australia today could emerge over timelines akin to what was considered ‘short-warning conflict’ in the past. While this warning time is likely to be measured in weeks or even months, such conflict would require the ability to activate large reserve forces, and to draw on significant civilian support for operations in Australia. Hence, the creation of these reserve capabilities, and maximising the legal and organisational ability to draw on civilian infrastructure and equipment, should be the priorities for mobilisation planning today.

This does not mean that force expansion is completely irrelevant. In the Cold War, conventional fighting in the northern hemisphere was expected to lead to nuclear escalation after the initial weeks or, at most, months of fighting. Hence, the raising of new units—or ‘mobilisation readiness’—was considered superfluous (and a practical impossibility, at least in Europe), and there were no significant preparations or plans to raise new forces in case of conflict. Today conflict may well be protracted, with fewer incentives for escalation of nuclear use to a scale that would render significant conventional operations impossible.

In protracted conflict, there may thus be a need to raise some new units to reconstitute and replace losses, and possibly to allow rotation of deployed forces for rest and recuperation.[75] In addition, changes in the strategic environment may well create new demands for wartime or peacetime deployment that could require an increase of the force for specific tasks: establishing permanent garrisons on Christmas and Cocos islands, or possibly—if agreement was reached—on the territory of countries to Australia’s north, for example. Hence, it would be prudent to identify credible contingencies of this kind as part of Defence strategic planning.

But planning for force expansion should not be seen as a substitute for addressing the need to create the forces required now, and the challenges of doing so. In this context, difficult questions may lie ahead about whether it is possible, with today’s demographics (and in light of persistent challenges of recruitment and retention despite increasing financial incentives), to raise the required regular and reserve forces through an all-volunteer force. In part, this raises the question of what the acceptable recruitment standards should be for a force that relies on mobilisation. But an increasing number of other Western democracies have concluded in recent years that similar demographic and strategic challenges require an increased reliance on conscription: Norway, Denmark and Taiwan have taken decisions to increase service times, increase numbers called up or include women in the draft; Lithuania and Latvia have reintroduced conscription; and in Germany, Romania and the Netherlands there are proposals from defence ministers to reintroduce conscription, albeit along Scandinavian models of a selective draft that preferentially calls up those among the whole cohort who state their willingness to serve.[76] Given persistent recruitment shortfalls, one may well ask at what stage Australia, too, might conclude that the potential of the all-volunteer force has reached its limit.

The 2024 DIPS states that ‘Defence industry is essential to … the development, delivery and sustainment of capabilities Defence relies on’.[77] This reliance is even greater during mobilisation when personnel numbers, and the number of platforms and systems to be utilised by those personnel is increasing. It is greater still during conflict as both platforms and consumables need to be replenished. In this sense, industry is more than just a FIC but a ‘capability in its own right’.[78] As the demands on industry for mobilisation in the land domain will be partly different from, and partly overlap with, the sea and air domains, Army needs to understand the industrial requirements and capabilities available to it, where offshore supply chains are sufficient and where domestic manufacture is a necessity.

The industrial system will need to adapt during periods of tension and conflict to provide the outputs upon which an expanded, high-tempo Army will rely. But the ability of the industrial system to adapt is an important constraint both on mobilisation and on the types of forces Australia can raise and sustain. It is therefore useful in this context to think of defence industry as comprising three different industries: for military platforms, for consumables (including ammunition), and for systems (especially sensor and communications) that are often dual use.[79] Newly raised forces—and existing forces after attrition and depletion of stocks takes its toll—will likely heavily lean into such capabilities that can be produced domestically and thus may have to be equipped, structured and operated quite differently from the way in which regular and even reserve forces do today.

Beyond examining mobilisation as an approach to force design and sustainment, it is also important to understand and manage mobilisation as a process that has to balance strategic, political and resource implications. Operationally the nature of littoral warfare in an age of long-range precision strike will likely create first-mover advantages.[80] Visible mobilisation measures are important signals to possible adversaries, and further examination is warranted of the potential value of formal—and publicised—levels of readiness as a tool of crisis management. Politically, governments will, however, also be concerned about controlling escalation, and the economic costs of such a step. Managing these tensions will require analysis of the signalling, military, economic and political aspects of different parts and phases of the mobilisation process—and how they would interact with the flow of US forces into Australia that would likely be a concurrent development in a crisis. Many such differences may be domain specific, and hence a worthwhile area for examination to understand the strategic characteristics of land power in the new environment.

In general, this assessment reinforces the need for politically and operationally realistic exercises to explore the strategic implications of mobilisation—as well as to put the mobilisation system itself under realistic stresses. Traditionally, realistic tests of strategic logistics have not been an important element of major Australian exercises, including in the Kangaroo series for operations in the defence of Australia. Australia has never had an equivalent of NATO’s Cold War Reforger[81] exercises, or of the large strategic mobility exercises that NATO has started again since 2014. There will be significant resource requirements for such exercises and, given the importance of Army’s reserve units, Army will have to play a major role.[82]

The consideration of mobilisation in defence policy is far from new for Australia. However, developing an effective system that can deliver significant capability through mobilisation in contemporary circumstances would be. As the policies discussed in this article form part of the intellectual and organisational legacy within which the Army operates today, it would do well to understand which approaches worked or not, and why.

Endnotes

[71] See Richard Brabin-Smith, ‘Do We Already Need the Next Defence Review?’, The Strategist, 1 March 2024, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/do-we-already-need-the-next-defence-review/.

[72]Defence Efficiency Report, p. E-2.

[73]Desmond Ball, ‘The Australian Defence Force and Mobilisation’, in Desmond Ball and JO Langtry (eds), Problems of Mobilisation in Defence of Australia (Canberra: Phoenix Defence Publications, 1980), p. 23. For other discussions of manpower considerations in force expansion at the time, see for example Babbage, Rethinking Australia’s Defence, pp. 184–208; JO Langtry, Manpower Alternatives for the Defence Forces, Working Paper No. 2 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1978).

[74]Peter Jennings, Andrew Davies, Stephan Frühling, James Goldrick, Mike Kalms and Rory Medcalf, Guarding against Uncertainty: Australian Attitudes to Defence, Report to the Minister for Defence (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2015), pp. 5–13.

[75]Noting that some of the most effective Ukrainian units have reportedly been in the line for up to two years, it would not be unreasonable to expect rotation on a similar timeline in Australia’s case.

[76]‘Ministry Considers Compulsory Questionnaire for Military Services’, Dutch News, 24 January 2024, at: https://www.dutchnews.nl/2024/01/ministry-considers-compulsory-questionnaire-for-military-service/#:~:text=All%20Dutch%20citizens%20between%2017,struggling%20to%20recruit%20new%20personnel; ‘Norway Follows Denmark with Plans to Conscript Thousands More Soldiers’, Euronews, 2 April 2024, at: https://www.euronews.com/2024/04/02/norway-follows-denmark-with-plans-to-conscript-thousands-more-soldiers#:~:text=Norway%20is%20to%20increase%20the,professional%20military%20expertise%20going%20forward.%22 ; Grzegorz Szymanowski, ‘Latvia Reintroduces Compulsory Military Service’, DW, 7 April 2023, at: https://www.dw.com/en/latvia-with-the-war-in-ukraine-conscription-returns/a-65257169; Iulian Ernst, ‘Romania Envisages Voluntary Military Service Scheme to Boost Reserve Force, Romania-Insider.com, 6 February 2024, at: https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-voluntary-military-service-plan-2024; Fabian Hamacher and Ann Wang, ‘Taiwan Begins Extended One-Year Conscription in Response to China Threat, Reuters, 26 January 2024, at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-begins-extended-one-year-conscription-response-china-threat-2024-01-25/. For a description of the ‘Scandinavian model’ of conscription, see Elisabeth Braw, Competitive National Service: How the Scandinavian Model Can Be Adapted by the UK, RUSI Occasional Paper (London: RUSI, 2019).

[77]Defence Industry Development Strategy, p. vi.

[78]Stephan Frühling, Kate Louis, Graeme Dunk and Jeffrey Wilson, Defence Industry in National Defence: Rethinking Australian Defence Industry Policy (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre and Australian Industry Group, 2023).

[79]Jonathan D Caverley, ‘Horses, Nails and Messages: Three Defense Industries of the Ukraine War’, Contemporary Security Policy 44, no. 4 (2023): 606–623.

[80]The analogy of railways in mobilisation in 1914 being a very disconcerting one.

[81]The REturn of FORces to GERmany exercised the flow of NATO reinforcements from North America (and other NATO allies) into Germany and generally involved the movement of several divisions across the Atlantic.

[82]The most recent NATO Steadfast Defender exercise included more troops than any since the last Cold War Reforger exercise, and was directly linked to alliance defence plans. See ‘NATO to Hold Biggest Drills since Cold War with 90,000 Troops’, Reuters, 19 January 2024, at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/nato-kick-off-biggest-drills-decades-with-some-90000-troops-2024-01-18/. See also Heinrich Brauss, Ben Hodges and Julian Lindley-French, ‘The CEPA Military Mobility Project’, Center for European Policy Analysis website, 3 March 2021, at: https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/the-cepa-military-mobility-project/.