- Home

- Library

- Volume 20 Number 3

- Contemporary Plan 401

Contemporary Plan 401

Prior to the Second World War, significant planning for land force expansion and broader mobilisation was undertaken by both the Australian Government and the Army. The Commonwealth War Book provided whole-of-government guidance for actions required prior to and during the outbreak of a major conflict, including specific direction to Army. It stated, that the implementation of Army’s plans prior to war are to begin with ‘the mobilisation and expansion of the fixed machinery for administration and training’.[i] Army’s own plans for expansion were consistent with this guidance. Its ‘Overseas Plan 401’ stated:

the object of these orders is to ensure that there shall exist for use in time of emergency, a considered plan for the enlistment, concentration, equipping, training and despatch of an expeditionary force for service overseas.[ii]

Importantly, both documents emphasised the criticality of improving operational and command and control (C2) structures, and of remediating the long lead times that had previously characterised capability and infrastructure development efforts.

For Army, people are at the centre of everything. People form the basis of Army’s contribution to the integrated force—the backbone of the land domain contribution. Army must maintain the necessary range of military skills, tactics, C2 and operational procedures to staff the integrated force, assuring combat proficiency, and to grow new capability during expansion. However, domain mastery takes time. Building and maintaining Army’s profession of arms is a collective and enduring effort. Staffing an expanded training system is burdensome to the field force. Indeed, military and national mobilisation requires a broad view of training. Planning a training system for major conflict must consider the preparation of soldiers (the individual human capability contributed to war), the sustainment of units deployed on operations (as both replacements and reinforcements), and the care of personnel upon conclusion of duties.

This article takes a historical perspective on the Australian Army’s mobilisation efforts in the past to highlight opportunities to adopt similar methods for the future force that are in line with national education and population constraints. It also assesses the shortcomings in guidance related to expansion of the training system to ensure we can adapt when, and if, required. To do so, the article first provides an overview of current training demands in the land domain. This is followed by an examination of historical approaches to mobilisation planning specific to the Land Domain Training System (LDTS), which highlights necessary considerations for implementing an expanded system. Next, the article reflects on hard-won lessons learned by Australia during several historical efforts to mobilise the force in response to impending crisis. The article concludes with a summary of recommendations for the future LDTS so that it can more effectively scale in response to Australia’s increasingly uncertain strategic demands.

Endnotes

[i] Department of Defence, ‘Army Measures’, Commonwealth War Book (Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1956), p. 2.

[ii] Australian Army, ‘Overseas Plan 401’, revised 1st September 1932, 54 COPY 27, series MP826/1, NAA.

The Defence Strategic Review (DSR) confirms the findings of the 2016 Defence White Paper that Australia no longer benefits from a 10-year strategic warning time for conflict. In response to this environment, the document includes an ‘urgent call to action’ for ‘higher levels of military preparedness and accelerated capability development’.[iii] Specifically, the DSR directs Defence to undertake ‘accelerated preparedness’ across key interest areas including workforce, supply, infrastructure, distribution and posture.[iv] Accelerated preparedness is conceived as all actions that enhance our warfighting capability and self-reliance in national defence.[v] In this sense, accelerated preparedness extends beyond Army and Defence, representing a whole-of-nation effort. Within the scope of this article, however, the concept of accelerated preparedness is constrained to mechanisms and activities that tangibly increase Army’s preparedness and therefore enhance the combat proficiency and survivability of land forces.

In considering this broader environment, government recognises that Defence planning must be aligned to a variety of strategic contexts across different time horizons. Three historically consistent scenarios that reflect possible future operational commitments for the ADF, and specifically the land force, are humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) tasks domestically and overseas; regional security/stability operations; and major conflict in the region.[vi] These commitments span the entire cooperation–competition–conflict spectrum, and represent various land force operational demands. However, if the requirement for a land power contribution is protracted, or if multiple operations are to be conducted concurrently, government would require a national defence capability that exceeds the capacity of the standing Army.

To differentiate between the types of operational demands, and their links to surge or force expansion, it is important to understand the various stages of mobilisation. Surge is the ability to mass a response to a short-notice requirement within current resources.[vii] Expansion, however, is an increase in defence capability by scale and/or scope by provision of additional resources, often through mobilisation.[viii] Extant Army doctrine outlines four phases of mobilisation, the first two of which align with surge, and the final two with expansion:

- Stage 1: Selective defence mobilisation

- Stage 2: Partial defence mobilisation

- Stage 3: Defence mobilisation

- Stage 4: National mobilisation.[ix]

Stage 1 does not have a major impact on the current force or the LDTS. Army’s standard preparedness levels enable responses for operations that are incorporated within Stage 1, like Operation Sumatra Assist[x] and the military deployment to Papua New Guinea in response to the landslide in Enga Province on 24 May 2024.[xi] Stage 2 is similar to the initial stage in that it occurs within extant resourcing. However, Stage 2 entails the sustainment of operational commitments, which places stress on the ability of the LDTS to generate ready forces for supplementation, either through readying Reserve elements, rotating deployed units or reinforcing those on operations. An example is the changes made to Army during the Afghanistan and Iraq era under the auspices of the ‘Enhanced Land Force’[xii] and Plan Beersheba.[xiii]

Stages 3 and 4 require the continuous maintenance of the whole ADF on operations—with concurrent plans to reinforce the ADF—necessitating a significant expansion in defence capability such as through a call out of Reserves and/or conscription.[xiv] An example of Stage 3 commitments was the Australian contributions to the Vietnam War. Rapid expansion of the LDTS was required to ready Reserve elements and staff for expanded operational commitments.[xv] Specifically for the Vietnam War, the Australian Government directed that Army plan to expand the land force by more than double—planning that was predicated on growth within the training establishment (in both workforce and infrastructure) to increase soldier throughput, and that required a shift in training continuums.[xvi] Stage 4 is unique in that it represents a whole-of-nation response, where government coordinates a national effort to enable ‘profound’ increases in capability for the defence of Australia. The LDTS within both Stage 3 and Stage 4 functions in an entirely different manner due to the intensity of operational commitments, changes to risk tolerance of government, and fundamental shifts in the structure of Army’s order of battle (ORBAT). [xvii]

In an environment characterised by strategic uncertainty, Army’s challenge is not the act of mobilisation itself—that is a government-led activity. Rather, as demonstrated by the role of the LDTS at each stage of mobilisation, Army’s challenge is its ability to prepare additional and resilient land capability for the integrated force in line with the operational demand. This includes remediating workforce challenges, addressing infrastructure constraints and resolving issues of supply. This challenge is more acute for an LDTS tasked with force expansion. Such stress on the LDTS, however, is ultimately fuelled by time constraints. If, for example, it was believed that Australia would face the prospect of major power conflict in 20 years (at a known point in time), government and Defence could steadily expand Army’s workforce in line with available resources and funding. However, due to the aforementioned reduction in strategic warning time and advances in weapons systems and technologies that reduce the benefits of geographic distance, the Australian Government is making decisions in real time about the capability and employment requirements necessary to achieve national defence (force application[xviii]). As the immediate focus is on remediating current identified capability gaps, these decisions are being made without widespread acknowledgement of the integral role that the force generation system plays in establishing and sustaining the ADF’s operational demand in the longer term.[xix] This reality highlights two key considerations: 1) Army should be planning for some level of expansion in capability; and 2) the force generation system, including training, must become a central strategic planning consideration if Australia is to deliver future capability at the point of need, and at the time of need.

Endnotes

[iii] Australian Government, ‘Current Strategic Circumstances’, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 25.

[iv] Ibid, p. 81.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Hannah Woodford-Smith, ‘Defining Land Force Mobilisation’, Australian Army Journal 20, no. 1 (2024): 117, at: doi.org/10.61451/2675066.

[vii] Richard Brabin-Smith, ‘A Framework for Assessing Australia’s Defence Strategic Review’, The Strategist, 10 March 2023, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/a-framework-for-assessing-australias-….

[viii] Richard Brabin-Smith, ‘Force Expansion and Warning Time (Part II)’, The Strategist, 9 August 2012, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/force-expansion-and-warning-time-part….

[ix] McCleod Wood, ‘Going All In: Stage Four Mobilization in the Australian Army and the Enduring Issues Related to Sustaining Professional Military Leadership’, thesis, US Army Command and General Staff College, 10 June 2022, at: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/trecms/AD1212120.

[x] Australian War Memorial, ‘Operation Sumatra Assist, Combined Joint Task Force 629 patch: Major PF Cambridge, Australian Defence Force’, collection item, 2004, at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1260345.

[xi] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Australia’s Response to the Papua New Guinea Landslide’, Crisis Hub, media release, 27 May 2024, at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/crisis-hub/australias-response-papua-new-guinea….

[xii] Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works, ‘Chapter 5: Enhanced Land Force Stage 2 Facilities Project’, Report 7/2009—Referrals Made August to October 2009 (Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2009), at: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_repre….

[xiii] Department of Defence, ‘Army Delivers Final Component of Plan Beersheba’, media release, 28 October 2017, at: https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/releases/2017-10-28/army-deliver….

[xiv] Wood, ‘Going All In’, p. 11.

[xv] Department of Defence, ‘A Compendium of Military Expansion in Australia’, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise (Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1981).

[xvi] Department of Defence, Selective Service (Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1965).

[xvii] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, p. 27.

[xviii] Jay M Kreighbaum, ‘Force-Application Planning: A Systems-and-Effects-Based Approach’, thesis, US School of Advanced Airpower Studies, March 2004, at: https://media.defense.gov/2017/Dec/28/2001861684/-1/-1/0/T_0056_KREIGHB….

[xix] Department of Defence, ‘Release of the Defence Strategic Review’, media release, 24 April 2023, at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2023-04-24/release-d….

The LDTS is an element of the force generation system that supports Army to deliver land capability to meet its evolving operational needs. The LDTS enables land force contributions to the integrated force by delivering trained personnel able to deploy on operations. In achieving this, the system is designed to meet fluctuating strategic demands and operational objectives. The Deputy G7[xx] Army, within Headquarters Forces Command,[xxi] broadly defines the LDTS as the strategy-led, integrated by design, scalable, sustainable, agile and threat-centric force generation system designed to address all of Army’s education, training and doctrinal requirements. The LDTS enables both individual and collective training, in order to ensure that each person and team is capable of delivering land power, as (and as part of) the integrated force. The LDTS’s role in enabling Army to scale is critical to notions of mobilisation and expansion. Scalability is the ability to deliver acceptable performance as demand grows.[xxii] In this regard, the LDTS acts as the mediating factor in Army scalability as it influences the quality of the land force’s combat power, as well as the actual delivery of capability (people) to the integrated force. Put simply, the LDTS determines soldier throughput and quality of skill. If additional soldiers are required to meet increased operational demands, resulting in force expansion, the LDTS will ultimately determine how far Army can grow.

In addition to the LDTS, other critical factors also affect Army’s capacity for force generation. Traditional workforce constraints such as the availability of qualified/trained personnel, time and infrastructure impede soldier throughput within the LDTS.[xxiii] Further, changes to Australia’s strategic environment are challenging traditional notions of how training in the land domain should be conducted. For example, rapid changes in capability (such as the introduction of a littoral manoeuvre capability, evolving exercise demands based on changes to force generation cycles, and the organisation’s dispersed geographic disposition) constrain Army’s capacity to expand training efforts in a manner that assures quality and quantity in throughput.[xxiv] Further information regarding these specific constraints is discussed below in the review of Australia’s history of mobilisation and expansion.

Contemporary operational requirements also demand higher standards of professional military education and technical expertise at the individual and collective level. Innovative and adaptive thinking, leadership, and the ability to effectively operate in teams, are skills that are built over time and are central to Army’s unique contribution to the integrated force and the achievement of its capability edge.[xxv] Further, land domain capabilities are increasingly complex and depend on a range of networked technologies that require specialist expertise. Growing this workforce requires long lead times and highly capable trainers with their own depth of experience.[xxvi] Shifts to minimum viable capabilities, as directed in the DSR,[xxvii] must be approached cautiously for the maintenance of skills requirements of specific trades. Similarly, it is also important to consider the relevance of ongoing operational demands combined with the time required to build deep domain and defence mastery—a point that is exacerbated in leadership structures of both officers and NCOs. It is therefore necessary to look to history for explanations of Army’s current training system and elucidate the possible demands of the future force, including possible expansion.

Endnotes

[xx] G7 is the NATO staff naming convention for Army (G) training (7).

[xxi] Forces Command’s mission is to generate land foundation, combat and specialist forces in order to enable the integrated force.

[xxii] Woodford-Smith, ‘Defining Land Force Mobilisation’, p. 113.

[xxiii] Gavin Long, ‘Volume 1—To Benghazi’, Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1—Army (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1961).

[xxiv] Ben James, ‘Army Training System Transformation’, The Cove, 19 March 2019, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/army-training-system-transformation.

[xxv] Department of Defence, ‘The Future Ready Training System’, Transformation Program Strategy (Canberra: Department of Defence, March 2020).

[xxvi] Department of Defence, ‘Army and Navy Adopt New Trades Training System’, media release, 2 February 2024, at: https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2024-02-02/army-and-navy-ad….

It is a well-known idiom, especially in the context of strategic learnings, that exact events may not be repeated, but history does rhyme. A lesser known forewarning from George Santayana is perhaps even more appropriate in the context of mobilisation and training land forces: ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’.[xxviii] The current LDTS represents the culmination of lessons learned since before Federation, with Australia’s military personnel first committed to conflict (in Sudan), followed by expansion of its land forces through a universal training scheme soon after.[xxix] Indeed, over the years, Australia has earned a high reputation for its land force training, successfully building international partnerships (particularly in the immediate region) and establishing the capability credentials of the Australian soldier.[xxx] The Australian Government’s review of Army in 2004 found that ‘the single most impressive aspect of the Army has been the level and depth of training we have seen amongst its members’ due to the ‘training standards and professionalism of the Army’s soldiers and officers’.[xxxi] The current LDTS has its genesis in hard-won lessons derived from critical junctures in Army’s evolution and Australia’s cultural military history, most notably related to the First and Second World Wars. This section outlines the strategic-level lessons learned from Army’s experience in planning to expand the training system and decisions made in execution, specifically for the Second World War, which remains Australia’s most recent experience of national mobilisation.

Contingency Planning—Overseas Plan 401

From 1933, the Australian Government began reinvesting in all services in preparation for a major conflict. This was initially triggered by the British Government’s discontinuation of the ‘Ten-Year Rule’.[xxxii] In particular, a Commonwealth War Book was prepared by the Department of Defence to provide ‘in a concise and convenient form, a record of all the measures that are involved in passing from a state of peace to a state of war’.[xxxiii] Further, by 1939, Army had established its own, aligned, mobilisation plan (‘Plan 401’) to raise, train, and sustain an expeditionary force of up to one division (with associated enablers). This force later became known as the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (2 AIF).[xxxiv] The organisation also maintained plans for limited or general mobilisation, to concentrate a field army of six divisions between Newcastle and Port Kembla for defence against an invasion.[xxxv]

Plan 401 is principally a recruitment-focused document, detailing the flow of individuals through the various gates and necessary administration requirements. However, there is provision for staffing and training as well as for the force structure that may be required.[xxxvi] Military authorities used existing pre-war military structures to organise and train volunteers. Additionally, these structures enabled the baselining of personnel constraints, particularly for the employment of the staff corps (permanent force) and delegations to recruit training depots (RTDs). The experience of First World War veterans and of the permanent cadre had to be apportioned appropriately between the field force and the training establishment. Establishments for these RTDs were provided by Plan 401, with each military district commandant empowered to appoint officers, NCOs and soldiers to these establishments for a maximum of three months without the need to meet usual selection standards.[xxxvii]

Additional training was generally divested to units to complete in location; there are minimal historical records of course content or approaches to training. Plan 401 states:

It will be a primary responsibility of Commanding Officers to ensure that the training of their units to fit them for service in the field is preceded with at once upon lines which will ensure the desired result with the least possible delay.[xxxviii]

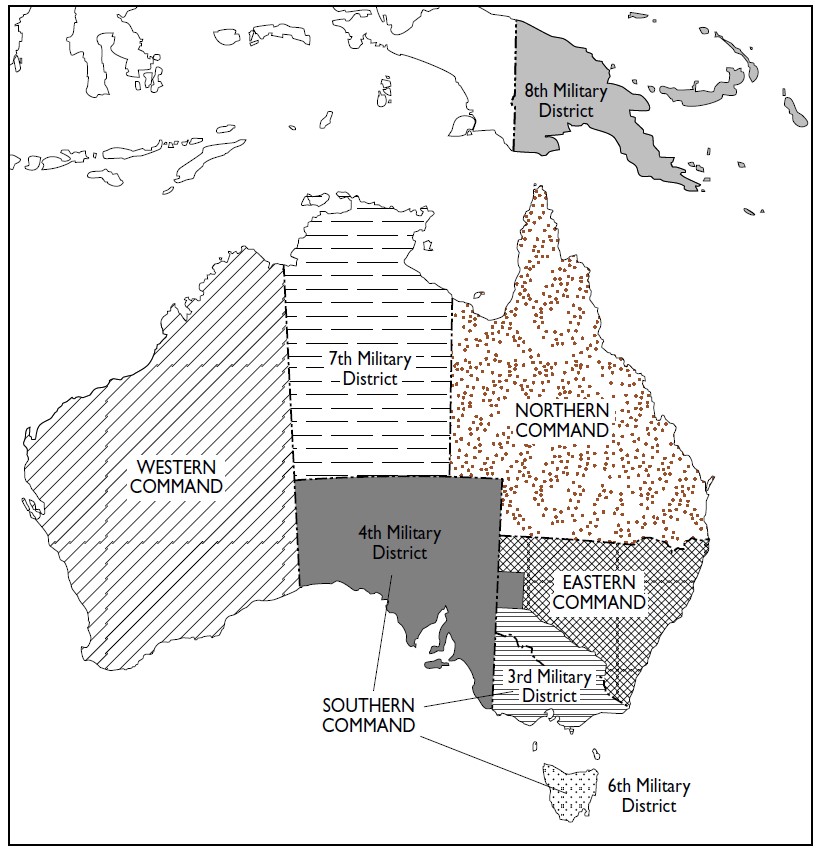

Importantly, it was the responsibility of these commanding officers to deploy on operations with their trained personnel—elevating the needs of effectively training the leadership cohort, and to ensure they were capable of accepting greater (or higher) duties when and if necessary. Training instructions were to be provided by the general staff, with subordinate instructions left to be developed by the military districts (a breakdown of military districts is at Figure 1).[xxxix]

Figure 1: Military districts[xl]

Overall, this type of planning demonstrates to the contemporary Army the necessity to consider the range of national defence contingencies that Australia may face—including the threat of major conflict. Within its planning, Army must forecast the type of establishment that might be required—particularly if force expansion is required. In particular, it is important to balance factors such as the apportionment of existing, and well-trained, personnel during expansion; the demand for credible[xli] land power; and the demand for qualified instructors in training establishments. Plans must also extend to detailed training instructions, at unit and headquarters levels, that are effected through formalised mission command structures that account for the temporal and geographic needs of Army. Finally, planning should position training and recruit-holding areas close to population centres across Australia to provide greater attraction and retention benefits to help grow and maintain Army’s people capability.

Generating Land Capability—Training as the Mechanism for Force Expansion and Sustainment

Prior to the commencement of the Second World War, the sustained expansion of the Army from 1938 saw increases to 2,266 permanent and 80,000 Citizen Militia Force (CMF) personnel.[xlii] By the end of the war, nearly 726,800 personnel had enlisted in the Army.[xliii] Using Plan 401, in 1939, the 6th Division was raised on a territorial basis, with units recruited from each state on a population-proportional basis (for example, New South Wales and Victoria each provided a brigade, while Queensland provided one-and-a-half battalions, Western Australia a battalion, and Tasmania half a battalion).[xliv] In December 1941, following the declaration of war by Japan, Army effectively conducted a second force expansion program,[xlv] with significant changes in organisational size, structure and C2.[xlvi] Of note, the requirement for rapid expansion, combined with the protracted nature of the Second World War, meant that Army’s training system was the key determinant in generating credible land capability and rapidly expanded the force.

The centrality of the training system to Army’s capacity for force generation was most evident in the constraints placed on force expansion by the inexperienced and hollow nature of the CMF. Notably, in 1920 it was recommended, based on experiences of the First World War, that the standard for initial training be no less than 13 weeks[xlvii] to render someone fit for combat.[xlviii] However, the professional standards expected by Army were not maintained, due to variability in service obligations and low attendance rates during peacetime. Specifically, CMF personnel did not spend significant time in training. At times, CMF personnel were only required to attend training for 16 days per year, and even this period was not always attended in full.[xlix] According to reports at the time, the standards of training were ‘not more than enough to produce a partially-trained soldier’ and would not be sufficient to staff an establishment spanning the planned new divisions.[l] However, standards of training were raised upon the outbreak of the Second World War, with the 6th Division benefiting from an extensive (though unintended) 15-month training period and training in theatre with partner forces such as the British. This length of training is one of a few factors that are widely credited with 6th Division’s success[li] on its first operation in the Middle East.[lii]

By October 1942, Army had reached its peak mobilised strength, with an establishment of 541,000 but an actual strength of around 519,000—split across both CMF (with service obligations on Australian territory that were extended to Australian-governed territories such as Papua New Guinea later in the war) and the AIF (for service obligations overseas).[liii] As the pool of eligible and interested recruits of military age and physical fitness shrank rapidly after the first 12 months, growing a force of this size depended on the introduction of selective service. Further, in 1942, at Army’s peak commitment, a monthly recruitment rate of 8,000 was required to maintain 2 AIF.[liv] By 1943, when plans were being made to reorganise Army to nine divisions, ‘wastage’[lv] for operations to defend Australia and Papua New Guinea was assessed at about 11,800 per month.[lvi] Demands were so high that recruitment from previously restricted populations was encouraged. These populations included regional partners (then Australian offshore territories) such as Papua New Guinea for recruitment into infantry battalions,[lvii] and Australian women, initially for recruitment into the Auxiliary Force.[lviii] The result was that Army had a significant number of recruits to sustain the operational demands on its forces.

Army was tasked with upskilling civilians and CMF personnel to a standard deemed ready to operate in garrison, field or other training units. In this way, mobilisation actions were largely beyond the remit of the Army to control; however, Army was required to manage the effects. This process, at the battalion level, generally commenced with the establishment of a nucleus of personnel (core headquarters functions) in the new unit’s location, which would take receipt of recruits that had passed through an RTD.[lix] Key headquarters staff would then promote individuals they felt were suited to higher duties, thereby enabling the administrative and training functions of the unit. Subsequently, basic individual training and some form of collective training (usually at the section or platoon level) would continue until the unit was embarked on operations.[lx] The ability of individual units to conduct training was essential to the expansion of the force at a time where training continuums did not exist. However, the strain this placed on the unit headquarters (and those tasked specifically with training) was immense. This liability should be factored into future planning—not necessarily as something that should be avoided but as something that should be managed closely. Further information regarding capacity issues in new units is explored in the next section.

This section has demonstrated the human-centred nature of capability development for Army. During force expansion Army may receive individuals who are required to serve but did not choose to. The profile of recruits may also be more diverse than has historically been the case, with greater proportions of individuals for whom English is a second-language and those who do not fit traditional stereotypes of the desired recruit. In response, training to achieve combat proficiency throughout the deployed force must accommodate variations in commitment and abilities among recruits. To overcome such challenges, Army must ensure its training is realistic and of sufficient duration. Doing so will enable a mixed workforce to achieve the organisational standards of defence mastery that are required of a professional land force.

Scaling a Training Establishment

Growing and contracting the training establishment during the Second World War was ultimately a test of flexibility for Army’s structure and policies. At times, training was conducted in theatre or in transit, though the preference was for it to be conducted in Australia.[lxi] For example, platoon-level training in the 6th Division was conducted in Australia, with the intention of completing all other required training in the Middle East under British instruction.[lxii] Time spent in training was similarly in a state of flux. In theatre, units completed three-month courses, which culminated in a three-week battalion exercise. In late 1940, training depots were established such that a training battalion was raised for each infantry brigade; and an artillery training regiment as well as a training regiment of reinforcements was raised for each cavalry and other unit.[lxiii] By 1943, however, training was considerably more standardised and reflective of operational demands. Recruit training consisted of an eight-week course. The recruit was then transferred to Land Headquarters (LHQ) for training on a further four-week course on jungle warfare. LHQ also trained each new officer for six-weeks in the duties of a platoon commander in jungle warfare.[lxiv]

Commenting on the initial state of training and unit formation, the Compendium of Military Expansion in Australia, published in 1981, stated that conditions were:

far from ideal … [with obvious] shortage of everything from weapons to uniforms and instructors. Although a quota of instructors from the permanent artillery and from the Instructional Corps was provided, it was not uncommon for a subaltern or sergeant to have to train a platoon single handed. Gunners did gun drill at Puckapunyal with logs.[lxv]

Other notable instances of poor equipment being provided include a rejection by the Treasury of an Army request to purchase motor vehicles for 2 AIF. The Treasury also denied funds to establish a modern artillery factory (to produce 25-pounder artillery pieces) and a second munitions plant to produce ammunition. The raising of the first three divisions in 2 AIF were highly dependent on provision of new modern equipment from British factories and stores, and the liberal use of British Army training establishments and instructors in theatre.[lxvi] Quantities of modern equipment were so severely depleted that some platoons only had a few rifles and one light machine gun. Meanwhile, some infantry units in 6th Division had been relegated to using wooden replicas of the weapons they lacked during training.[lxvii] Force expansion pressure experienced during the Second World War highlights the extent to which the training establishment is dependent on fundamental inputs to capability[lxviii]—a fact that remains highly acute for personnel.

Tension between the force generation system and the field force stressed the available workforce, particularly among officer cohorts and senior NCOs. AIF recruitment suffered most from a lack of experienced NCOs. This led to special classes of instruction being held at training centres in the military districts to produce NCOs who could instruct. Highlighting judgements made during this time, one officer claimed:

‘Owing to the lack of NCOs transferring from the Militia, officers, including company commanders, were compelled to handle extremely large squads for all types of instruction, as well as personally running NCO classes for selected privates. Also lack of ammunition, and the paucity of Lewis and Vickers machine guns and three-inch mortars reduced individual training in these to a minimum. It was hard enough to get dummy hand grenades, let alone live ones’.[lxix]

As highlighted above, training was also initially constrained due to issues of supply and available infrastructure. Training camps for AIF personnel were established near all major cities, with temporary accommodation and facilities set up at racecourses, showgrounds and exhibition grounds to house personnel before the camps were ready.[lxx] Permanent camps were established at Enoggera (Queensland); Liverpool and Menangle (New South Wales); Broadmeadows, Seymour and Bendigo (Victoria); Mitcham (South Australia); Blackboy Hill (as it was then named) (Western Australia); and Claremont (Tasmania).[lxxi] However, with the expansion of Army in 1943, Australia needed more training establishments. Schools and training establishments such as the Land Headquarters Training Centre (Jungle Warfare) at Canungra (established in November 1942), a Staff School, an Armoured Fighting Vehicle School, a Small Arms School, a School of Military Engineering and a School of Military Intelligence were created during this time.[lxxii] As a result, by 1944 Army possessed ‘an extensive educational system’ providing technical and advanced training in all aspects of modern warfare.[lxxiii] By the end of the Second World War, approximately 40 schools, in geographically dispersed locations, had been established and more than 96,000 courses had been run.[lxxiv]

The extensive growth achievable during the Second World War is indicative of an adaptive army. In response to increased demand, Army proved itself to be flexible in both establishment and thought. In terms of the actual expansion or contraction requirements of the training system, Army used a risk-based approach informed by concurrency pressures and the sustained generation and administration of capability. Underpinning efforts to scale the training system was the availability of officer and senior NCO cohorts. Today these experienced individuals remain essential to the force generation system and, as such, their continued supply needs to be managed for the force-in-being and applied within any force expansion plan. Further, the successful growth of Army’s contemporary training system depends on continued innovative thinking (on both infrastructure and training environments). Beyond these human factors, however, Army’s ability to deliver quality training inevitably depends on the availability of fundamental inputs to capability and a willingness to flexibly use equipment and other forms of supply.

Endnotes

[xxvii] Australian Government, Defence Strategic Review, p. 91.

[xxviii] George Santayana, The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense (New York: Dover Publications, 1980).

[xxix] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, p. 7.

[xxx] Tom Frame (ed.), The Long Road: Australia’s Train, Advise and Assist Missions (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2017).

[xxxi] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, ‘Chapter 9: What Is the Measure of Our Army?’, From Phantom to Force: Towards a More Efficient and Effective Army (Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2004), p. 193.

[xxxii] David French, Deterrence, Coercion, and Appeasement: British Grand Strategy, 1919–1940 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

[xxxiii] Department of Defence, ‘Army Measures’, Commonwealth War Book (Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1939).

[xxxiv] Australian Army, Overseas Plan 401.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Ibid.

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Department of Defence, ‘AHQ Instructions for War—Training—Special Intensive Training’, 14 September 1938, NAA 35/401/397.

[xl] Albert Palazzo, The Australian Army: A History of Its Organisation 1901–2001 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[xli] Credible in this context is a highly important and nuanced concept. Credible land forces are lethal and are able to persist in degraded, contaminated and dangerous environments to create dilemmas for adversaries and maximise survivability across domains.

[xlii] Carl Herman Jess, ‘Report on the Activities of the Australian Military Forces 1929–1939’, n.d., AWM 20/9 Part I.

[xliii] Joan Beaumont, Australian Defence: Sources and Statistics (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 306.

[xliv] Craig Stockings, Bardia: Myth, Reality and the Heirs of Anzac (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009), pp. 29–33.

[xlv] ‘John Curtin: Announcement that Australia Is at War with Japan, 1941’, audio clip, National Film and Sound Archive, JCPML00282/1, at: https://john.curtin.edu.au/audio/00282.html.

[xlvi] Graham R McKenzie-Smith, The Unit Guide: The Australian Army 1939–1945 (Newport: Big Sky Publishing, 2018).

[xlvii] This fluctuated throughout the war, in line with operational demand and service obligations. For example, from 1942, recruits under the age of 20 were required to undergo six months of training before posting to a unit (see Mark Johnston, ‘The Civilians Who Joined Up, 1939–45’, Journal of the Australian War Memorial, November 1996, at: https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/journal/j29/civils).

[xlviii] Department of Defence, ‘Report on the Military Defence of Australia by a Conference of Senior Officers of the Military Forces’, 1920, AWM1 20/7.

[xlix] ‘First Report by Lieutenant General E.K. Squires, CB, DSO, MC, Inspector-General of Australian Military Forces, December 1938’, AWM 54, 243/6/58.

[l] Ibid.

[li] A trend that was unfortunately not continued. The multitude of factors that contributed to later failings during the Second World War are beyond the scope of this paper.

[lii] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, pp. 34–35.

[liii] Jeffrey Grey, The Australian Army: A History (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 140.

[liv] Ibid., p. 150

[lv] Wastages include in-theatre combat deaths, injuries, other issues of health and respite periods.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Anna Edmundson, ‘Green Shadows—the Papuan Infantry Battalion’, National Archives of Australia website, 30 April 2024, at: https://www.naa.gov.au/blog/green-shadows-papuan-infantry-battalion.

[lviii] McKenzie-Smith, The Unit Guide, Volume 6.

[lix] Ibid.

[lx] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, pp. 34–37.

[lxi] McKenzie-Smith, The Unit Guide, Volume 6.

[lxii] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, pp. 34–35.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Ibid.

[lxvi] Ibid.

[lxvii] Ibid.

[lxviii] Department of Defence, ‘Fundamental Inputs to Capability’, Defence Capability Manual (Commonwealth of Australia, 4 April 2022), at: https://www.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-07/Defence-Capabili….

[lxix] Major George Smith quoted in David Hay, Nothing Over Us: The Story of the 2/6th Australian Infantry Battalion (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1984), p. 15.

[lxx] Department of Defence, Chief of the General Staff’s Exercise, p. 34.

[lxxi] Ibid.

[lxxii] Ibid.

[lxxiii] Palazzo, The Australian Army, pp. 153–54.

[lxxiv] Ibid.

As demonstrated above, the Second World War experience, supported by some experiences in the First World War, was the basis upon which Army formulated its present training requirements. These critical events helped define tolerable training standards and methods, forced the identification of new training locations, and highlighted the demands placed on the limited fundamental inputs to capability—particularly experienced personnel. The overarching lessons of Army’s training experience in the world wars have been taken seriously. In subsequent periods of peace and during low-intensity conflict, Army has been able to adopt these lessons to their fullest extent, such as overtraining to prevent injury and death; ensuring experienced Army personnel instruct on courses to impart their unique knowledge; and exercising individually and collectively on repeatable scenarios to build intellectual and practical reflexes. These lessons are the fruit of Army’s lived experience. With the benefit of deep domain mastery characteristic of a professional military, and supported by an effective force generation system, the Australian Army is able to achieve a level of asymmetric influence that belies the relatively small size of the land force. Maintaining and enhancing the training system will enable Army to expand again should the need arise. As stewards of the LDTS, the obligation exists for those tasked with designing and implanting it to maintain complete awareness of how and why Army’s training system has evolved, in order to inform future decision points and to identify options for change if required.

In seeking to address the requirements of the land domain’s future training needs, Army has already committed to dispersed training arrangements, enhanced training environments leveraging the benefits of training and learning technology, reduction of ‘time in training’, and modularisation of courses. These are all critical transformation initiatives but they are narrowly focused on changes necessitated by the emerging strategic environment. The LDTS must look further, to the types of scenarios the future force may be presented with, and to the larger establishment it may be tasked to generate. Decisions required for longer lead time capability generation need to be made now.

Army’s Future Training Challenge

Based on history and Australia’s current strategic guidance, Army must be prepared to adequately generate and sustain land power, as part of the integrated force, possibly for prolonged high-intensity operations. Consequently, Army must take measures to scale up to a force that is larger than the force-in-being while simultaneously sustaining directed commitments.

Central Idea—a Contemporary Plan 401

Leveraging the experiences of the Second World War, the LDTS must be capable of adequately preparing land forces to be deployed and sustained at the ‘speed of relevance’ in response to emerging needs. In the context of strategic mobilisation, the term ‘speed of relevance’ refers to the pace of action required to prepare and generate land power equivalent to operational demand. Additionally, ‘need’ is defined as the expansion of the ADF to meet severe and/or multiple concurrent crises; its adaptation to rapidly field new or repurposed capabilities; and the endurance required to meet prolonged periods of high-tempo activity in a manner that is nationally sustainable.

Army’s history of generating an expanded force highlights key training system requirements for a mobilised future force. These considerations should be factored into any contemporary Plan 401. They include:

- balancing risks in quantity and quality as well as between readiness and growing the training establishment—including through protecting certain workforce cohorts and/or establishing shadow establishments or learning programs to enable rapid decision-making if required

- identifying opportunities to integrate, partner or outsource training

- understanding the population base of recruits—in terms of both skills opportunities and limitations in learning ability (such as language)

- understanding the integrated training requirements—identifying whether Army may be responsible for wider Defence, or even whole-of-government/nation, education needs in the land domain

- seeking innovative solutions to remediate capability limitations—in terms of both training locations and conditions of training

- as part of this process, reviewing the extant policy that supports our system across a number of strata and making preparations to change it if the context changes.

These demands are only relevant to a training system capable of expanding Australian land forces; unique approaches are warranted when considering naval and air capabilities. While the nature of land power needs is broadly understood, there remain extraordinary opportunities to further investigate how to optimise a modern army training system. Realising such a system will involve engagements across Defence, government and industry and, in response to cultural evolution within Army and modern safety considerations, will inevitably require changes to means and methods of training.

Endnotes

Adequate preparations must include the development of plans that enable the land force to expand. Such plans must specifically address the ways in which the force generation system can grow in line with operational demand. This means they must include instructions on ways to:

- build flexibility into the workforce/people management system—through capability-based employment specifications, open architecture, enhanced resourcing, and better outcomes for Defence personnel. This may also include further modularisation of training and a shift toward service category (SERCAT) neutral training where such an approach is appropriate to achieve total workforce outcomes

- leverage integration—to harness the full resources of Defence, industry, allies and partners

- train the trainer now—to build an expanded cohort of experienced officer and NCO instructors

- conduct threat-centric training—to build enhanced threat literacy and to focus training and education efforts on most likely / most dangerous pacing threats

- identify latent experience in the Australian population—such as among veterans or people with equivalent civilian skill sets

- establish learning continuums and learning objectives that are appropriate for maintaining the force-in-being in competition, and for expanding the future force in response to enduring high-intensity conflict—possibly including through shadow postings, shadow training programs or shadow learning management packages

- remediate equipment supply, particularly for Reserve units, for training schools and for a larger force—something that will require better integration across the Defence enterprise and (in a time of national mobilisation) the national support base

- overcome capacity issues in units and headquarters to prioritise training—removing non-essential tasking where appropriate and enabling a greater proportion of Army personnel to be available for training and education

- realign and build resilience into training locations—endeavouring to ensure alignment with population centres

- enhance use of existing facilities—such as running some training environments 24/7

- increase the use non-defence training areas (NDTAs)—to enhance the sophistication of training environments beyond fixed defence training areas

- adopt novel technologies and techniques to meet the changing character of war and enhance training capacity—considering live, virtual and constructive ranges and infrastructure; using alternative methods of training delivery, like simulation; and leveraging the democratisation of devices at the individual level (for example, Army personnel can learn a language via an application on their personal smartphone, tablet or similar device anywhere and at any time)

- develop an instructor culture that can rapidly accept new technologies and demographics (whether they be cultural, gender, experience or service based)

- consider alignment of Army training with the national skills framework to easily recognise civilian qualifications.

Any review of Army’s historical experience in growing an expanded force during national mobilisation efforts is necessarily reductive. A full examination of the changes that were made to Army’s training system both during the world wars and subsequently in response to them would be an expansive undertaking beyond the scope of this article. Accordingly, this article has not provided a full review of factors such as C2 structures, the calculations that informed cost-benefit analyses of force ratios, and the actual time expended in training among various trades. While the recommendations proffered in this article are therefore necessarily limited and broad in nature, they are nevertheless valuable. The intent is to situate these considerations within broader debates about military mobilisation; to help generate the kind of thinking that exists only in a multidisciplinary setting—engaging academia, specialists in industry, former and current serving members, who all have relevant experiences to share among the profession of arms.

Endnotes

The size and structure of the Australian Army has never been static. Army has expanded and contracted in response to operational demands and the politics of the day. The organisation has responded to demands of major conflict without adequate levels of preparedness—particularly in the First World War. Prior to the Second World War, government was able to fund steady increases to Army’s size, while the organisation itself developed contingency plans on how to grow further to deliver an expeditionary force as well as allowing for the defence of Australia. This planning, formalised for Army in Overseas Plan 401, was integral to realising a force generation system that could effectively deliver new land capability from additional resources granted to Army by government. The plan was limited in some details—divesting the development of significant portions to regional units—but it provided the signposts for force expansion. While the lack of detail that characterised the plan reflected, in part, the infancy of Army writ large, it is nevertheless still useful as it highlights the foundations required to grow a land force: enlistment, concentration, equipping and training.

Today Army does not control enlistment or supply arrangements, and has limited authority over force concentration. However, Army does control the pivotal aspect of its force generation system: the LDTS. In particular, the LDTS plays a considerable role in mobilisation and force expansion, scaling land capability in line with operational demand. Indeed, Army’s ability to use its training system to expand and contract the size of the force, and to generate personnel with sufficient defence mastery, has been ultimately determinative of its ability to deliver national defence capability as and when needed. This is a particularly salient point in considering current and future force generation demands.

The quality of Army’s people and teams is dependent on threat-centric training, which establishes individual and collective literacy on the most likely and most dangerous pacing threats. History shows that the fluctuation in Army’s training system (in both size and form) is intimately tied to the readiness of the field force—the organisation cannot staff training establishments with experienced and qualified trainers if they are simultaneously required for operations or to promote and staff newly established headquarters. Army’s ability to expand in response to contingency scenarios will continue to be determined by the availability of experienced trainers, by military priorities and by the unique requirements of the strategic situation. As it stands, the LDTS may not enable Army to deliver capability quickly enough to meet the emerging strategic demands identified by the Australian Government. Further, uncertainty about when, if and how such a contingent scenario—like major conflict—could evolve, combined with the time required to develop trade, domain and defence mastery, will challenge any attempt to expand the current Army.

Such uncertainty requires a response now, in line with government calls for accelerated preparedness. In particular, prompt action should be considered to address the opportunities presented by this article, such as building flexibility into the workforce/people management system and resourcing innovative and novel methods of training. These opportunities should also be considered against extant plans and concepts to ensure they enhance and contribute to building the desired force generation system. It may not be possible to achieve the desired end state within extant resourcing. Nevertheless, making choices now can act as a hedge against Australia’s worst-case scenario. Army faces the same questions now as it did in response to all previous defence and national mobilisation events: how can demands on the field force be balanced against the stressors that are transferred to the force generation system? This article contends that perhaps the answer lies in the Commonwealth War Book and Overseas Plan 401: before the commencement of conflict, Army must prioritise efforts to establish resilience in the fixed machinery of war—in the administration of the land force and its training.