Exploring the Value of Deployed Military Chaplains in Australia’s Region

Introduction

Following the fall of Kabul to the Taliban on 15 August 2021, the Australian Government authorised a non-combatant evacuation operation to ensure Australians and other approved foreign nationals could safely leave Afghanistan. Between 18 and 26 August, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) flew 32 flights to and from Hamid Karzai International Airport, transporting a total of 4168 people. This included 2,984 Afghan visa holders, who were former locally engaged employees and their families now at risk if they remained in their country.[1] Once out of Afghanistan, Australian aircraft flew them to a staging area established at Al Minhad Air Base in the United Arab Emirates, from where they would eventually be flown to Australia. To support this operation, Defence deployed over 300 additional personnel to the Middle East, one of whom was Islamic Imam and Royal Australian Navy Chaplain Mogamat Majidih Essa.[2] As many of those fleeing Afghanistan were Muslims, Essa offered a unique and possibly encouraging presence. For those awaiting flights to Australia, he held Friday prayers (Salāt al-Jumu’ah), an important weekly ritual within the Islamic faith, and daily services. ‘It was my first Friday prayer I’ve conducted in the ADF’, he remarked at the time. ‘Under the circumstances of the congregation, they were very supportive and happy that we were able to conduct Friday prayer for them.’[3]

Essa migrated to Australia from South Africa in 2007, joining the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in 2016. The Australian National Imams Council had nominated him for the position of chaplain after it had been approached by the Navy’s Chaplaincy Branch, which was seeking to diversify its membership.[4] In some ways, Essa reflects the modern ADF, or at least what it aspires to be. The Pathway to Change: Evolving Defence Culture 2017–2022 program sought, in part, to build a diverse workforce with an inclusive culture to ‘harness the diverse backgrounds and experiences of those in our teams to deliver a capable and agile joint fighting force’.[5] In other ways, however, Essa is increasingly out of step with current social trends within the organisation. A recent article in the Australian Army Journal noted that in the past two decades the demographic composition of the ADF has changed, such that a majority of its members now profess no religious affiliation.[6] This situation reflects wider demographic changes in Australia as a whole.

Yet Essa’s role during the evacuations from Afghanistan serves as a reminder not only that religion is still important to many around the world but also that the ADF’s chaplains can offer a unique capability to a deployed force. This article examines the persistence of religion as a global phenomenon, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, and then explores the ways in which chaplains have contributed to military operations and activities beyond their traditional pastoral and sacramental roles. While not all these initiatives were necessarily successful, they nevertheless show how commanders have called upon the religiosity of their chaplains, making creative use of their distinctive position as uniformed ministers of religion. As the place of religious chaplains within a functionally secular organisation like the Australian Army is increasingly questioned, there is merit in considering how a padre’s religiosity could be of value to the land force when deployed overseas, especially to areas where religion is highly influential to a local population.[7]

Religion and the Indo-Pacific

In 2009, Tom Frame, historian and former Anglican Bishop to the ADF, suggested that the majority of Australians appeared to have ‘quietly abandoned religious affiliation or become gently indifferent to religious claims’.[8] Statistical data supports this observation. For example, the 2021 Census showed that while Christianity was still the most common religion in Australia (43.9 per cent), its adherents had dropped to below 50 per cent of the population for the first time. The number of Muslims had grown to 812,392, although this represented a mere 3.2 per cent of the Australian population. Importantly, a record 38.9 per cent of people reported having ‘no religion’, up from 30.1 per cent in 2011 and 22.3 per cent in 2011.[9] The growing ambivalence about religion was captured in other ways. Several recent studies have shown that while Australians agree that respecting religion is important within a multicultural society, most consider religion to be a personal and private matter, and that religious people should ‘keep their beliefs to themselves’.[10] Furthermore, when asked about the attributes that defined Australians’ sense of identity, religion was placed last, with political beliefs, nationality, gender (particularly for women) and language the primary identity markers.[11]

While religion might be in decline in Australia, it retains its strong influence abroad. In December 2022 the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project observed that in certain parts of the world, such as South Asia and South-East Asia, religion remained a central facet of life. For instance, 93 per cent of Indonesians and 80 per cent of Indians considered religion very important in daily life, while only 18 per cent of Australians responded similarly.[12] Further, the project found that that while the United States, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand were growing less religious, the vast majority of the world’s population was projected to still adhere to a religious worldview. In addition, population growth projections forecast that the percentage of the global population that is religiously unaffiliated will shrink in the decades ahead, such that most of the world’s population will likely continue to identify with a religion. It was projected that between 2010 and 2050 the number of Christians—as a share of the global population—would remain constant (31.4 per cent), the number of Muslims would likely increase from 23.2 per cent to 29.7 per cent, the number of Hindus would decline slightly from 15 per cent to 14.9 per cent, and the number of religiously unaffiliated people would decline from 16.4 per cent to 13.2 per cent.[13]

These demographic projections have implications for professional militaries. In 2020, the US Joint Staff released guidance on behalf of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff concerning strategic religious affairs. This guidance noted:

Outside of Western Europe and North America, populations that hold to historic religious faiths continue to increase. This growth, coupled with shifting immigration trends, presents important issues for the Joint Force. It challenges our understanding of how religion motivates and influences allies, mission partners, adversaries, and indigenous populations and institutions.[14]

The importance of religion as an operational factor was also evident at lower levels. One US academic (and former Marine Corps infantry officer) recalled an exchange during a lecture at the US Naval War College where a student stated that they did not feel comfortable discussing religion overseas. A US Marine Corps colonel with three tours of Iraq interjected, stating that failure to consider religion would be the equivalent of issuing orders without considering the weather: it would be nonsensical and morally irresponsible.[15] While US personnel might have a heightened appreciation for the importance of religion given its influence in their country, this does not invalidate the reflections of those who spent two decades grappling with complex warfighting in a highly religious social and cultural context.

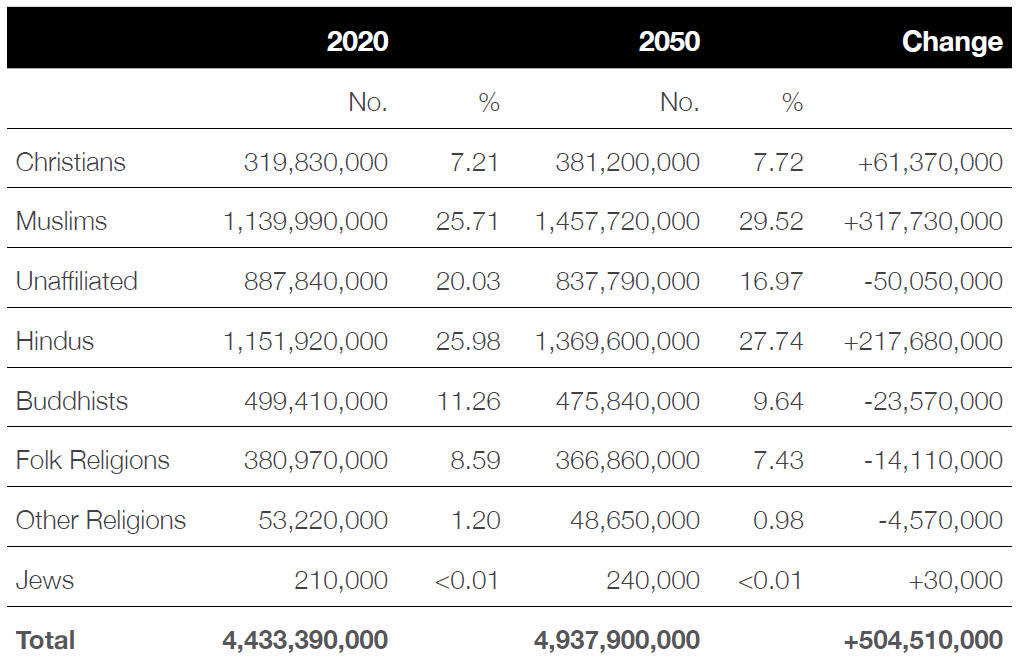

The intersection of religion and military affairs is particularly important when considering the Indo-Pacific, which the 2023 Defence Strategic Review declared to be ‘the most important geostrategic region in the world’ and the primary area of military interest for Australia’s national defence.[16] According to the Global Religious Futures project, not only does the Indo-Pacific region include a large proportion of people with a religious affiliation but also the number of adherents is projected to increase (Table 1). Australia’s northern neighbours all have strong and diverse religious cultures. For instance, Indonesia, with a population of 263,910,000 in 2020, has an estimated Muslim population of 229,620,000, or 87 per cent of the population. By 2050, the total population is expected to increase by 33,350,000 and the Muslim population by 27,200,000.[17] Elsewhere, much of Papua New Guinea’s population is made up of Protestant Christians, while Timor-Leste is an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic country, albeit that in both countries there is a syncretistic mix of Christianity and traditional animistic practices in rural areas.[18]

Table 1. Indo-Pacific estimated religious composition, 2020 and 2050 (projected)

Source: Pew Research Center, ‘The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050’

There is no future scenario in which the Australian Army will have no need to engage with those in Australia’s immediate region—either in the form of bilateral or multilateral defence relationships or in an operational capacity. Accordingly, Army personnel will inevitably interact with those who hold not just different religious affiliations but also differing views on the importance of religion. If, as the demographic projections suggest, religion will remain a feature of the Indo-Pacific for some time, it is only sensible to consider how best to relate to it. The prevalence of religion as a feature of global life makes it difficult to ignore, despite the Australian preference to treat it as a private matter. As argued by John D Carlson, a US religious ethicist and Commander in the US Navy Reserve, the suggestion that the military should have nothing to do with religion is ultimately untenable, because:

religious belief is simply too important, too enduring, too ineradicable from the way that many human beings live to ignore. That leaves us with another option: engage the complexities of religion in ways that are attentive to the nuances, challenges, and dangers.[19]

If religion is ineradicable, as Carlson suggests, how might the Army’s religious component, the Royal Australian Army Chaplains Department, be of value to the land force in ways beyond its traditional focus towards the pastoral and wellbeing support of serving members? The remainder of this article will identify four broad categories of roles that military chaplains have performed in recent decades that go beyond these functions to include faith-based diplomacy, religious advisement, and religious leader engagement in both peace-support operations and counterinsurgency (COIN) operations. In each example, the specific religiosity of military chaplains offered a unique capability to a deployed force on operations, exercises and activities abroad, although not always without risks and caveats.

Faith-Based Diplomacy

In recent years, Australian Army chaplains, and those of other services, have been involved in diplomatic engagement with regional nations. During Operation SOUTH WEST PACIFIC ENGAGEMENT 19, engagement with local religious leaders was instituted as an important component of the operation. Chaplains from the 7th Brigade and others, under the lead of the 1st Division/Deployable Joint Force Headquarters (DJFHQ), engaged with religious leaders in Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Tonga. It was the view of one chaplain that commanders:

need to appreciate that if they wish to well connect with a village, the first person disembarking from the helicopter needs to be the padre. The padre will meet the local religious leaders, who will then introduce him to the village headman and then the rest will be taken care of.[20]

While people are potentially prone to overstate their own influence, it is true that many communities in the South Pacific hold to Christian beliefs which they actively practice and, crucially, incorporate into their political and diplomatic discourse.[21]

Chaplains have also been involved in INDO-PACIFIC ENDEAVOUR, the ADF’s flagship regional engagement activity. This annual activity sees elements of the RAN, Army and RAAF collaborate with regional counterparts to undertake activities ranging from seminars and tabletop exercises to passage of lines exercises at sea, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief coordination activities.[22] For instance, as part of Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2022, Chaplain Essa visited the Maldives, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Harnessing the importance of religion within family, community and national life in those countries, he met religious and other leaders to help build and develop regional partnerships. ‘When we take the religious faith of our neighbours seriously’, he argued, ‘it shows that we take them seriously. It’s seen as a real indicator of respect.’[23] Major Sarah Wilkinson, the gender adviser on HMAS Adelaide, observed Essa leading evening prayers. ‘It was clear to see that our Malaysian and Indonesian guests appreciated religion being taken seriously’, she remarked.[24]

The integration of religion into the conduct of international peacemaking and statecraft is known as faith-based diplomacy.[25] It grew in prominence through the 2000s and 2010s, such that in 2015, US Secretary of State John Kerry argued that understanding and engaging with religion was ‘one of the most interesting challenges we face in global diplomacy’, adding pointedly that ‘we ignore the global impact of religion at our peril’.[26] While the impetus and opportunity to integrate religion into the broader international diplomatic system began to wane towards the end of the decade, in local contexts, such as the ADF’s engagement with regional partners, the practice continued.[27] In 2018, Dr Marigold Black, a research fellow at the Australian Army Research Centre, cited the ADF’s history of using its chaplains in a diplomatic capacity to question whether faith-based diplomacy needed to be incorporated into the conduct of Australia’s foreign relations. In her view:

While [Australian practitioners] should take care not to compromise Australia’s fundamental values and they should pay attention to how those [faith-based] initiatives might be received by allies and future friends, it seems short-sighted not to provide formal and informal diplomatic forces with the most useful, flexible and influential toolkits.[28]

As a general observation, Australia’s multicultural and pluralist society might give the ADF a comparative advantage over other regional powers, as it can draw from a diverse pool of recruits with religions in common with regional neighbours. Essa’s experience suggests the importance of having chaplains (and service men and women in general) of varied faith traditions, particularly Muslims given the demographic composition of the Indo-Pacific. As one Christian chaplain argued:

The benefits of appointing representatives from other faith traditions in the current geo-political environment are obvious. A person who shares Australian values, from an Islamic viewpoint for example, would be invaluable in dialogue with Islamic leaders.[29]

One modest and practical recommendation concerns the representation of Muslims within the Army. With the anticipated growth of Islam in the Indo-Pacific, and the need to build and sustain military diplomatic ties with Muslim-majority nations in Australia’s region, the Army would do well to have a greater number of Muslims and potentially imams in its ranks.

Religious Advisement

Another operational role for chaplains is to support commanders and their staff to appreciate and understand the religious dimension of a local population in which their forces are operating. As doctrine acknowledges, it is no longer realistic for a military force to conduct operations on battlefields devoid of any other actors except the opposing military force.[30] Within this context, everything an armed force does, or does not do, may influence local perceptions of the ADF. Doctrine writers have argued:

These perceptions can be positive or negative, accurate or false, but often result in actions (or reactions) by civil actors and those whom they influence, which have the potential to support or significantly hinder the achievement of the military mission.[31]

The challenge, therefore, is to understand the local population and civil actors, consider the consequences for them of military presence, posture and activity, and then develop plans which maximise their support and minimise disruption to them.[32] Absence of local knowledge was felt when the Army began deploying battlegroups to southern Iraq in 2005. The first rotation, Al Muthanna Task Group 1 (AMTG-1), was led by Lieutenant Colonel Roger Noble. Within his area of operations, religion and religious leaders were highly influential, yet the Australians’ understanding about religious groupings and Islam remained low throughout the deployment. A key lesson Noble took from the deployment was the importance of understanding the human terrain.[33]

While the task of briefing a commander on any relevant features of a battlespace remains the remit of intelligence officers, some have argued that chaplains are well suited to offer advice on matters relating to local religion. During the 1999 Kosovo War, Supreme Allied Commander Europe, General Wesley Clark, used his senior command chaplain, Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, as his principal adviser on matters of religion, ethics and morals.[34] The Balkan region is well known for its blend of religions and cultures, and adherents to Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism and Islam are found among the population. Resnicoff’s experience in Kosovo informed his belief that it was ‘foolish’ to send an intelligence officer to learn about religious and ethnic aspects of a particular area when (he believed) chaplains were more readily suited to this task.[35] Canadian Armed Forces chaplain Steven Moore, who had served in Bosnia in 1992 and 1993, argued that, after fulfilling their primary role of sacramental and pastoral support—what he termed the ‘Internal Operational Ministry’—chaplains could extend their support on operations to ‘External Operational Ministry’ activities. In his view, the first such activity was the conduct of ‘religious area analysis’: determining the basis for what people do and why they do it with respect to religion.[36] He posited:

As credentialed clerics, the advanced theological training of chaplains and additional skills development positioned them to better interpret the nuances of religious belief that often escape detection—something that could be very costly to a mission.[37]

The US military has been formally considering the chaplains’ role of ‘religious advisement’ for longer than the ADF. It encompasses the provision of materials, briefings, reports, summaries and counsel to warfighting commanders concerning the role that religion and culture play in a specific theatre of operations. It can require the chaplain to become an expert on matters of local religions and cultural context in order to provide situational awareness of the relevant sensitivities of a place and its inhabitants.[38] Despite this formalisation in US military doctrine, questions remain concerning how effective a chaplain can be in this role, especially if they are being asked for advice and information concerning a different faith tradition to their own. While some have argued that chaplains have natural expertise and inclinations in this area as they are familiar with religion, it is by no means clear that the expertise chaplains have in their own religious milieu would naturally translate into locally relevant knowledge.[39] Indeed, not all chaplains offering advice to commanders in Iraq or Afghanistan were successful, and in some instances chaplains knew less about religion in their area of operations than the commander did.[40]

Within Australia’s region, particularly Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and the islands of the South Pacific, Christian chaplains are on surer footing. For instance, during the 1999 INTERFET deployment, Senior Chaplain Len Eacott (an Anglican) and Catholic padre Graeme Ramsden often briefed Headquarters INTERFET on religious issues, such as the importance of Catholic holy days.[41] More recently, in November 2018 the ADF undertook Operation APEC 18 ASSIST in support of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting being held in Port Moresby. At the time, various Protestant denominations represented 69.4 per cent of the population of Papua New Guinea, and Roman Catholicism a further 27 per cent. Because of his familiarity with the interdenominational nuances of various Christian traditions, during the operational planning phase the 1st Division/DJFHQ chaplain was able to assist the Joint Intelligence Cell in interpreting the religious composition of the city.[42]

An Australian ambassador who had firsthand experience working alongside the ADF on peacekeeping operations in Timor-Leste argued that an integral element of both diplomacy and peacekeeping was gaining an ‘understanding of the culture, the history and the mind-set of the people with whom you are working in order to best reach out to them’.[43] While obvious caveats apply regarding the level of knowledge chaplains might have about the religious practices of any given geographic area, when their confessional traditions align, chaplains have proven themselves capable of providing commanders and their staff officers with a valuable perspective on issues to which they might not otherwise have access.

Religious Engagement in Peace-Support Operations

Liaison with local religious leaders and communities is another operational role for chaplains that has emerged over recent decades. In 2002, Dr Douglas M Johnston, an American sailor and scholar who founded the International Center for Religion and Diplomacy, outlined the potential benefits. Specifically, he argued that military chaplains could engage with local religious communities in an operational area to gain more information about the ‘religious and cultural nuances at play’, pass on concerns of indigenous leaders about emerging threats to stability, offer a reconciling influence in addressing misunderstandings or differences, and advise commanders on potential religious or cultural implications of their decision-making.[44] Johnston became a key advocate for what became known as ‘Religious Leader Engagement’. Johnston’s characterisation is consistent with Moore’s concept of the External Operational Ministry, which acknowledges the chaplains’ role in engendering trust and establishing cooperation within communities by engaging local and regional religious leaders.[45]

The assumption behind the designation of liaison responsibilities to chaplains stems from the notion that religious leaders wield significant influence in many societies and thus have the potential to aid or disrupt attempts to influence the local population. ‘What the Mullah shares at Friday prayers’, one Australian chaplain stressed, ‘can inflame hatred, mistrust and violence against foreign troops or it can encourage cooperation based on an accurate understanding of the mission and attitudes of those troops and their commanders.’[46] Indeed, the influence of religious leaders, both overseas and in Australia, was identified by health officials during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they appealed to leaders to support vaccine rollouts in their communities.[47] Similarly, in a military operational context, gaining the trust of local religious leaders is regarded by many as a means to facilitate better engagement and cooperation within the broader community. Advocates argue that, in their capacity as both clergy and military officers, chaplains can act as intermediaries and bridge-builders in ways that are unachievable by other uniformed personnel. This is because the chaplains’ symbolic religious status, authority and theological expertise bring a unique depth and authenticity to their engagements.[48]

While the practice of chaplains engaging with local clergy on operations had prior historical antecedents, it emerged in its modern form during the 1990s, especially amid UN peacekeeping operations in the Balkans following the dissolution of Yugoslavia. In this context, the liaison was predominantly oriented towards supporting post-conflict reconciliation.[49] In 1993, for instance, chaplains operating as part of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in Bosnia engaged with Croat Roman Catholic, Bosniak Muslim and, later, Serb Orthodox leaders in order to better understand the needs of various communities and, in time, to help build trust and develop common ground between the military forces and local communities.[50] The practice was soon incorporated into US joint doctrine, largely as an extension of civil–military affairs. For example, the 1996 iteration of US Joint Publication (JP) 1-05, Religious Ministry Support for Joint Operations, stated that chaplains might be required to coordinate with host nation civil or military religious representatives ‘in order to facilitate positive and mutual understanding’.[51] There were, however, debates as to how far this role should extend, with some arguing for an active role for chaplains in religious leader engagement while others preferred that they focus instead on supporting their own forces.[52]

In the Australian context, local religious engagement was undertaken in East Timor during the INTERFET mission. While standard pastoral care and sacramental responsibilities took up much of their time, many Australian chaplains worked closely with local communities, religious orders, seminaries and parish churches. Chaplains would make regular visits to churches to speak with priests, nuns and village leaders, relaying local concerns and the needs of the peacekeeping forces.[53] Chaplains would also assist in the sensitive and important task of body retrievals and burials, as well as preaching or celebrating Mass at Sunday services.[54] These activities were undertaken despite a perception, among chaplains, of reluctance within Headquarters INTERFET to engage directly with the Timorese church and its officials. ‘It would have given us instant credibility’, Graeme Ramsden later argued, ‘provided access to the largest and best-organised group in Timor, and to Tetum speakers, and overcome a lot of initial communication difficulties.’[55]

Engagement was driven at lower levels where its effects were more keenly felt. For example, a Roman Catholic padre, Glynn Murphy, was with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment at Balibo near the Indonesian border. In the absence of a local priest, Murphy undertook to ring the Angelus daily from the church belltower, an action which, in his words, was ‘a constant, stubborn invitation for any refugees hiding in the hills to “come home”’.[56] Once the local priest returned, services eventually resumed, with hundreds flooding back into the church. The gradual resumption of services in towns within the border districts, usually under INTERFET protection, was an important way to normalise the security situation.[57] As observed in a 2005 US Air Force research paper that examined the role of military chaplains as peacebuilders, ‘religion is best viewed as a force useful in stability operations rather than an issue to disregard or overcome’.[58]

The impact of Murphy’s actions impressed the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Mick Slater. When Slater returned to Timor in 2006 as a brigadier leading the 3rd Brigade on Operation ASTUTE, he requested Murphy (who was then chaplain to DJFHQ in Brisbane) to join him in Dili to engage once again with the local population as part of stabilisation operations. Slater remembered and well understood the importance of Roman Catholic faith in Timorese society and how valuable Australian chaplains could be in achieving his mission. On his return to Dili, Murphy set about reconnecting with the priests and nuns to hear their concerns. Once again, he celebrated Mass alongside Timorese clergy, symbolising that Australia remained a friend of Timor-Leste.[59]

One person who recognised the valuable role that Army military chaplains played on Operation ASTUTE was the Australian Ambassador in Dili, Margaret Twomey. An experienced diplomat, she recognised that Australian diplomacy and operational activity in response to the 2006 crisis needed to work hand in glove to create space for the Timorese to resolve the issues that had instigated an outburst of intercommunal violence. Once Brigadier Slater’s force arrived, its chaplains began to connect with local parishes and clergy. ‘I saw the almost immediate deployment of ADF chaplains assume a powerful complement to the initial construct of Operation Astute’, she recalled.[60] She recognised that Timor’s overwhelmingly Roman Catholic identity had been an historically unifying force, and that Australian Catholic padres could, by virtue of their status as priests, cross linguistic barriers through the common rituals of church and of prayer. ‘The ADF chaplaincy’, she reflected, ‘while not known to be at the forefront, performed a special role during Operation Astute. One for which I, as a diplomat, am greatly appreciative.’[61]

More recently, Army chaplains have engaged with local communities in Fiji on Operation FIJI ASSIST and in Solomon Islands on Operation LILIA.[62] In nation-building and post-conflict environments such as Timor-Leste, as well as in more recent humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief missions in the South Pacific, religious leader engagement has served as a practical way to learn about the needs of the local population and to facilitate aid and support. It has also offered a military force a means to connect with the community of potentially greater depth and resonance than an ordinary civil–military affairs/civil–military cooperation team. In Timor-Leste, one historian concluded, the status of Australian padres gave them ‘unrivalled acceptance and unparalleled respect in local communities’.[63] On Operation FIJI ASSIST, senior members of the ADF task group expressed their surprise that religious leader engagement was able to open doors and provide valuable insights into key people and situations in the area of operations. Formally, the task group Commander Land Forces, Lieutenant Colonel John Venz, observed that religious leader engagement was highly effective in a forward-deployed role.[64] Within such contexts, it is evident that chaplains undertaking local engagement have much to offer.

Religious Engagement in COIN: a Bridge Too Far?

Following the al-Qaeda terrorist attacks against the United States on 11 September 2001, the US military soon found itself at war in both Afghanistan and Iraq. Once on the ground in an unfamiliar land, among a foreign culture, and charged with undertaking stability operations, some commanders began using their chaplains in religious leader engagement roles to build bridges with local communities. As the missions in both countries slowly evolved into counterinsurgency operations, there was an increasingly pressing need to gain consent from the local population for military activities. This meant that establishing and maintaining positive relations with local populations was a precondition for mission success. Some commanders believed that their chaplains could be used to help resolve misunderstandings, dispel detrimental stereotypes about Western nations and, where possible, solve problems. Such efforts aimed to increase the perceived legitimacy of other coalition efforts, thereby improving local cooperation and inducing greater acceptance of the military presence in any given area.[65]

An early example occurred when the 101st Airborne Division arrived in northern Iraq in May 2003. Its commander, Major General David Petraeus, ordered his chaplains to begin developing relationships with local clerics in the hope of building trust and countering misinformation about US forces.[66] US Army chaplains thus began meeting local religious leaders and hearing their concerns, many of which concerned local detainees.[67] Soon, Chaplain John Stutz, working within the division’s Civil-Military Operations Centre, became the primary contact person between the public and regional detainees. Among other tasks, he regularly arranged for imams to visit and interview detainees held by the division. He also participated in weekly meetings with the Council of Imams and the Council of Bishops, where he requested that the religious leaders encourage the local population to return stolen items ransacked from public buildings, including museums. Much to his surprise, over several weeks many items were returned.[68]

Similar activities were conducted in Afghanistan, where religious leaders, particularly at the district and village levels, were regarded as representatives of their community and important powerbrokers, able to legitimate or de-legitimate the Afghan government in Kabul.[69] Operating in Helmand Province, II Marine Expeditionary Brigade developed a religious leader engagement program using a US Navy Muslim chaplain (specifically deployed for this task) as an ‘icebreaker’ in discussions with clerics in southern Afghanistan. At a local level, these discussions had a positive effect: engagement in the Golestan District, Farah Province, for instance, opened the way for the local Marine company commander to communicate better with the community and help address their needs by linking them with the government in Kabul.[70]

Religious leader engagement in Afghanistan was not merely the domain of US chaplains. British chaplains undertook tasks similar to those of their American peers, meeting with local populations, distributing articles for use in worship and in Qur’anic study, and taking part in individual and group discussions with local mullahs.[71] In the midst of the Afghanistan campaign, senior clerics from Helmand Province even urged that British imams be deployed to Afghanistan to counter Taliban claims that British Muslims were oppressed and to explain Islam to British soldiers.[72] Chaplains from Canada, New Zealand and Norway were also to be found supporting the work of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs).[73] One notable Canadian chaplain in Afghanistan, Leslie Dawson, was surprised that her gender did not create obstacles in engaging with local mullahs. At meetings where she was the only woman present, she was often warmly received and asked many questions about her role as a woman and a chaplain.[74]

Anecdotally, many Christian chaplains found that their faith background was not necessarily a barrier to engagement with Islamic leaders, and it was repeatedly demonstrated that chaplains of other faith traditions need not dilute their own confessional positions in order to engage with Muslim leaders.[75] Some even found that being a religious figure afforded them a degree of status in an environment where clerics were highly regarded, and some were afforded the same respect as a local mullah.[76] On other occasions, there were demonstrable benefits to the overt inclusion of military chaplains on operations within Muslim communities. Specifically, it helped counteract perceptions that troops from Western secular nations were devils, infidels or non-believers.[77] Even small acts of engagement, it was argued, could potentially have a powerful influence in breaking down negative stereotypes about Western militaries and the secular nature of their home countries.[78]

For the ADF in Uruzgan province in southern Afghanistan, several chaplains sought to develop relationships with local and Afghan National Army (ANA) mullahs. While some commanders endorsed the practice (if, at times, cautiously), others retained their chaplains for traditional internal welfare and command support roles. Chaplain Stephen Brooks, who served with Reconstruction Task Force 3 (RTF-3), built up a relationship with the local ANA mullah that culminated in the announcement that the mullah and his representatives (ANA religious officers), if asked, would accompany the PRT and RTF-3 on visits to local communities to spread a message of goodwill about Australian and coalition efforts.[79] Conversely, the chaplain deployed on RTF-4, Ian Johnson, fulfilled a more orthodox inwards-looking role.[80]

Chaplain John Saunders of Mentoring Task Force 3 (MTF-3) was perhaps the most forward-leading Australian padre in Afghanistan. Having been convinced of the need to engage with local Muslim leaders as part of the battlegroup’s mission, he was cautiously given approval to contact ANA mullahs and local communities by his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Chris Smith, and the Combined Team Uruzgan deputy commander, Colonel Dave Smith. His approach was twofold: first, he became a conduit through which Qur’ans from the Australian Islamic community could be gifted to Afghan Muslims, intent on countering misinformation spread by the Taliban that coalition soldiers were ‘crusaders’ determined to overthrow Islam. In this way, Saunders hoped to demonstrate that Muslims and non-Muslims live in harmony together in Australia. Second, he acted as a mentor to the ANA religious officers (who were more akin to welfare officers), mirroring the mentoring role undertaken by other parts of the battlegroup.[81]

By Saunders’s account, he was well regarded by the local Uruzgan mullahs, and he became known as the ‘Australian mullah’. He was even given an Arabic name, ‘Hamza’ (meaning ‘brave and strong’), due to his efforts to understand the Muslim faith and his willingness to materially assist them where he could.[82] Yet while Lieutenant Colonel Smith had endorsed Saunders’s initiatives, he was generally unconvinced about their utility in the broader scheme of the Afghanistan campaign. This, it must be noted, reflected his view concerning all attempts to win ‘hearts and minds’ through various forms of local engagement. While Smith believed that such activities had their place, he did not view them as the decisive element within the campaign against the Afghan insurgency. Instead, he adhered to the view that any success was due to the application of force and violence. If the international forces were unable to prevent the Taliban from killing the local population, then any local engagement and reconstruction work would mean little.[83] No amount of local goodwill generated by his chaplain was going to help defeat the Taliban at a strategic level.

When MTF-3 handed over to MTF-4, the mullahs and religious officers were apparently keen to continue the dialogue and mentoring with the incoming Australian chaplain.[84] For his part, Saunders’s successor, Chaplain Martin Johnson, was restricted from continuing the practice of local engagement. Following unrest that arose after reports in February 2012 that US soldiers at Bagram Air Base had burnt Islamic religious material, the Australian contingent became apprehensive about having Qur’ans in its possession. With the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kahlil Fegan, concerned about safety, Johnson gave a box of Qur’ans to the local mullah, rather than distributing them individually as Saunders had done as he travelled around the area of operations. Johnson continued to engage with local mullahs and was encouraged to do so, although for security he was rarely alone with the mullahs and would always be accompanied by an Australian soldier. Amid concerns about insider (Green-on-Blue) attacks, Johnson stressed to Fegan that he believed the safety and welfare of the troops was dependent upon building sound relationships with the Afghans and he was determined to play a role in that endeavour.[85]

How much the efforts of Australian chaplains contributed to the mission in Uruzgan is hard to measure given their small numbers and the ad hoc way in which they were tasked to engage with the local community. Still, Saunders emerged from his experience in Afghanistan as an advocate for religious leader engagement. In his view, the high levels of religious observance in both Asia and the Pacific meant that the niche capability of chaplaincy would be ‘a task force necessity irrespective of the type of operations in which we find ourselves engaged in the future, be that warfighting or disaster response’.[86] In this, he was not alone. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan prompted several chaplains to advocate for the formalisation of religious leader engagement in doctrine and training to better prepare chaplains for similar tasks in future operations.[87] The most comprehensive effort came from Canadian Armed Forces chaplain Moore, whose doctoral thesis on the religious peacebuilding of chaplains included field research with the Kandahar PRT in 2008.[88] Other chaplains wrote smaller studies outlining the advantages of using chaplains in more operational roles.[89]

Despite the enthusiasm with which many chaplains made their case, doubts remained over the appropriateness of religious leader engagement in the context of counterinsurgency operations. Most positive reports on the practice came from chaplains themselves: there are few available testimonies from local clerics or their populations to corroborate the effect engagement had on them.[90] Many examining the practice from an external perspective had reservations. While religious leader engagement might have had demonstrable merit in peace-support operations and post-conflict environments, critics were cautious about its suitability in active conflict zones. A major moral and legal concern is that under Article 24 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, as well as the Geneva Protocols of 1977, chaplains are protected personnel in their function and capacity as ministers of religion, to be respected and protected in all circumstances.[91] They were, therefore, accorded non-combatant status, because, like medical personnel, they were understood to be undertaking humanitarian duties within a force of combatants, not directly undertaking combat themselves (hence they were usually unarmed). This meant that, chaplains were at risk of losing their non-combatant status if they operated in support of psychological operations or leveraged local opinion to gain military advantage.[92]

While advocates such as Moore argued that religious leader engagement functioned as peacemaking rather than direct support of tactical objectives, this categorisation does not suit Afghanistan and Iraq, where chaplains belonged to a military force actively fighting against insurgents. In this operational environment, gaining the support of the local population afforded the force greater tactical advantage, and it was therefore inevitable that religious leader engagement took on operational characteristics. While seemingly benign, such activities ultimately advanced coalition military objectives, even if that was not the predominant purpose. In reality, the risk always existed that chaplains could be instrumentalised and that their faith—and the faith of those with whom they engaged—could be exploited for tactical purposes.[93] Similarly, chaplains had the potential, either intentionally or unintentionally, to stray into the collection and dissemination of human intelligence while liaising with local religious leaders.[94]

While religious engagement in a counterinsurgency context entailed genuine risks to chaplain safety, perhaps more concerning was the risk posed to those with whom military chaplains liaised. Local leaders who established relationships with military chaplains could readily come be regarded by hostile groups as collaborating with occupying powers and treated accordingly. If nothing else, this risk encouraged chaplains to think deeply and cautiously about the utility of engagement.[95] The risk also existed that chaplain engagement within local communities could be seen as a front for proselytising particular religious values among target populations. This concern was most pronounced among chaplains from faith traditions, such as evangelical Christianity, who view conversion as a central tenet of their religious practice.[96]

Many of the challenges of implementing religious leader engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan would no doubt be replicated should the Australian Army be required to conduct COIN operations in Australia’s region. Last century the Australian Army spent many years fighting insurgencies in South-East Asia, and the conduct of another regional COIN campaign cannot be discounted as a possible future requirement. While the prevalence and importance of religion in the Indo-Pacific might encourage some chaplains to consider the ways in which they could serve in a liaison capacity, commanders would need to weigh the benefits carefully, keeping in mind the risks to all involved.

Institutional Limitations

Regardless of whether a chaplain is operating in a combat or a peacekeeping context, there is inevitable variance among individual capabilities. Not only do chaplains have different levels of inclination to become involved in work beyond ministering to the deployed force, there is no rigorous systemic training for such activities to be anything other than ad hoc and almost totally reliant on individual competence. There is also a natural limit to how much a single chaplain can achieve. A particular chaplain might establish a good relationship with local clerics, but it becomes incumbent on their successor to have the willingness, aptitude, temperament and comfort to continue the work in order to ensure its ongoing success.[97] This cannot always be guaranteed.

One of the main criticisms of religious engagement with the local population—one raised by chaplains and commanders alike—is that it takes a chaplain’s energy and attention away from their primary pastoral and sacramental responsibilities. Those primary responsibilities are to attend to the spiritual, pastoral, welfare and morale needs of their troops, their officers and the commander. Indeed, this is a key reason why some chaplains have misgivings about the practice.[98]Some feel they lack the training and experience to engage with local leaders effectively, while others are uncomfortable with security risks, particularly as chaplains are usually unarmed.[99] From a commander’s point of view, even when chaplains have the willingness and capability to perform a local engagement function, it is often preferable to have the padre remain focused internally to ensure that those under their command receive adequate spiritual and welfare support. In an extended discussion in a Small Wars Journal forum on this issue, battalion and brigade commanders were often the most hesitant to encourage a widely expanded formal role for the chaplain.[100]

Many of the criticisms of religious diplomacy and engagement by military chaplains were addressed by advocates like Johnston and Moore, and then in US joint doctrine (formal Australian consideration of such matters has taken longer to develop). For example, the 2018 US Joint Staff definition of chaplain liaison in support of military engagement is ‘any command-directed contact or interaction where the chaplain, as the command’s representative, meets with a leader on matters of religion to ameliorate suffering and to promote peace and the benevolent expression of religion’. This definition specified a narrow and focused role that addressed religion in human activity without employing religion to achieve a military objective. Activities were to be command directed, rather than purely on the initiative of the chaplain themselves, and chaplains were to ensure that they did not compromise their non-combatant status, function as intelligence collectors, engage in manipulation and/or deception operations, take the lead in formal negotiations for command outcomes, identify targets for combat operations, or use their engagements as occasions for proselytising.[101] Yet as US Military Academy historian Jaqueline E Whitt argued:

Although JP 1-05 mandates that chaplains should take no actions that might jeopardize their special status, there is almost no specific guidance as to what this might mean in practice, in effect, leaving such decisions up to individual chaplains and commanders.[102]

The flurry of discussion within professional military circles on the role of chaplaincy came about at a time when the United States and its allies were fighting two wars in highly religious environments, where religion was key to understanding the conflict. As these wars have receded from view, less has been written on the topic, particularly about the practice of religious leader engagement. While it continues to have its advocates, its efficacy and suitability in kinetic operations remains questionable.

Conclusion

It is said that armies reflect the values of the nation to which they belong. If that is so, religious chaplains are, at least superficially, increasingly out of place in the Australian Army. Yet militaries, and in particular land forces, need to be prepared to operate in the world that is—not the one some might wish it to be. Rather than relegating religion to a private and personal matter for individuals, commanders and policymakers would do well to consider how to incorporate religion into operations and activities to advance Australia’s interests abroad. Ultimately, it is not important to consider how much value Australians place on religion. The reality is that for many populations beyond our shores, it is a central social institution, particularly within the Indo-Pacific countries with which the Army routinely engages. If the ADF is serious about strengthening engagement with Indo-Pacific partners, incorporating religion into this endeavour in a meaningful way can only support this task.

Over several decades, chaplains have shown how their position as ministers of religion could serve deployed forces on operations beyond their traditional inwards-serving roles. While religious leader engagement in counterinsurgency and genuine warlike operations poses any number of problems for chaplains and their commanders, the use of chaplains to engage with local populations within the context of peacekeeping, peace-support operations and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief has demonstrable value. Functionally, many of the factors outlined in this article—faith-based diplomacy, religious advisement and religious leader engagement—potentially work in unison on operations.

Nothing in this discussion is intended to detract from a chaplain’s core function of tending to the welfare and the spiritual health of their own flock. As Moore argued, this ‘has always been and must continue to be the principal focus of deployed chaplains’.[103] Nevertheless, this analysis has shown why chaplains need to be capable—and willing—to undertake these expanded roles, preferably trained and well prepared for the functions they are directed to undertake. The fundamental message remains: religion is operationally important for land warfare. As the Army considers the future of the Royal Australian Army Chaplains Department, there is merit in reinforcing how religious chaplains can offer unique tools at a commander’s disposal. This article provides the basis for better informed discussion on this topical issue.

About the Author

William Westerman is a lecturer in history at UNSW Canberra, with research expertise in the First World War. A Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, he is also the author of the Official History of Australian Operations in Iraq, 2003-2011 and co-author of the Official History of Australian Peacekeeping Operations in Timor-Leste, 2000-2012. Among his other work, he has written a history of the 1996 merger of the Fitzroy Lions in the Australian Football League.

Endnotes

[1] Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Australia’s Engagement in Afghanistan: Interim Report, January 2022, pp. 84–85.

[2] Ibid., p. 83.

[3] Max Logan, ‘Multi-Faith Chaplaincy Provides Support’, Defence News, 11 September 2021.

[4] ‘Padres Head Up Support’, Defence News, May 2019.

[5] Department of Defence, Pathway to Change: Evolving Defence Culture 2017–22 (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2017), p. 7; Department of Defence, Annual Report 2021–22 (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2022), p. 108.

[6] Philip Hoglin, ‘Secularism and Pastoral Care in the Australian Defence Force’, Australian Army Journal XVII, no. 1 (2021): 103.

[7] Ibid., pp. 98–111; Steve Evans, ‘Ex-Chaplain Questions Ongoing Role of Christianity in Armed Forces’, Canberra Times, 3 July 2022, p. 13.

[8] Tom Frame, Losing My Religion: Unbelief in Australia (University of NSW Press, 2009), p. 4.

[9] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘2021 Census Shows Changes in Australia’s Religious Diversity’, media release, 28 June 2022.

[10] Monica Wilkie and Robert Forsyth, Respect and Division: How Australians View Religion, Policy Paper 27 (The Centre For Independent Studies, 2019); Annabel Crabb, ‘What Australians Really Think about Religion’, ABC News website, 6 November 2019, at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-06/annabel-crabb-australia-talks-religion-insights/11674076 (accessed 31 January 2023).

[11] Crabb, ‘What Australians Really Think about Religion’.

[12] Pew Research Center, ‘Key Findings from the Global Religious Futures Project’, 21 December 2022, at: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/12/21/key-findings-from-the-global-religious-futures-project (accessed 19 July 2023).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Instruction CJCSI 3070.01, ‘Strategic Religious Affairs’, 30 October 2020.

[15] Chris Seiple, ‘Ready … or Not?: Equipping the U.S. Military Chaplain for Inter-Religious Liaison’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 7, no. 4 (2009): 43.

[16] Department of Defence, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), pp. 27–28.

[17] Pew Research Center, ‘Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050’, 21 December 2022, at: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/interactives/religious-composition-by-country-2010-2050 (accessed 7 August 2023).

[18] Office of International Religious Freedom, ‘2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: Papua New Guinea’, US Department of State website, 2 June 2022, at: https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom/papua-new-guinea (accessed 7 August 2023); Michael Gladwin, Captains of the Soul: A History of Australian Army Chaplains (Newport: Big Sky, 2014), p. 282.

[19] John D Carlson, ‘Cashing in on Religion’s Currency: Ethical Challenges for a Post-Secular Military’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 7, no. 4 (2009): 55.

[20] Quoted in Charles M Vesely, ‘Regional Key Religious Leaders: Chaplains Adding Value to Mission’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, 2019, p. 66.

[21] Marigold Black, ‘Faith-Based Diplomacy in the New Strategic Order’, The Strategist, 10 October 2018, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/faith-based-diplomacy-in-the-new-strategic-order (accessed 9 August 2023).

[22] John Blaxland, ‘The Army’s Patchy Engagement with Australia’s Near North’, in Craig Stockings and Peter Dennis (eds), An Army of Influence: Eighty Years of Regional Engagement (Cambridge University Press, 2021), p. 381.

[23] Andrew Thorburn, ‘Faith in Bridges of Respect’, Defence News, 5 December 2022.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Brian Cox, ‘The Nature of Faith-Based Diplomacy’, Institute for Faith-Based Diplomacy website, 4 January 2020, at: https://www.ifbdglobal.org/post/the-nature-of-faith-based-diplomacy (accessed 24 July 2023).

[26] John Kerry, ‘John Kerry: “We ignore the global impact of religion at our peril”’, America: The Jesuit Review, 2 September 2015.

[27] John Fahy and Jeffrey Haynes, ‘Introduction: Interfaith on the World Stage’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 16, no. 3 (2018): 4.

[28] Black, ‘Faith-Based diplomacy in the New Strategic Order’.

[29] Martin A Johnson, ‘Positioned to Service: Military Doctrine and the Missio Dei in the RAAChD’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, 2018, p. 62.

[30] Australian Army, Land Warfare Doctrine LWD 3-8-6 Civil-Military Cooperation (2017), p. 11.

[31] Ibid., p. 12.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Noble to author, email, 13 July 2023, held by author.

[34] William Sean Lee, Christopher J Burke and Zonna M Crayne, Military Chaplains as Peace Builders: Embracing Indigenous Religions in Stability Operations, CADRE Paper No. 20, Air University Press, Alabama, February 2005, p. 15.

[35] Tom Roberts, ‘Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, Retired Navy Chaplain, Found Humanity amid War’, National Catholic Reporter, 10 November 2017.

[36] Steven Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement: An Emerging Capability for Operational Environments’, Canadian Military Journal 13, no. 1 (2012): 44.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Eric Patterson, ‘The Modern Military Chaplaincy in the Era of Intervention and Terrorism’, in Eric Patterson (ed.), Military Chaplains in Afghanistan, Iraq and Beyond: Advisement and Leader Engagement in Highly Religious Environments (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014), pp. 14–15.

[39] Stacey Gutkowski and George Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy: A Contribution to Debate over the Roles of US and British Military Chaplains in Afghanistan’, Religion, State & Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 116.

[40] Douglas M Johnston, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains: Redirecting a Critical Asset’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 7, no. 4 (2009): 30.

[41] Graeme Ramsden, Letters From Timor (Newport: Big Sky, 2011), p. 132.

[42] Vesely, ‘Regional Key Religious Leaders’, p. 64.

[43] Margaret Twomey, ‘Timor Leste 2006 ADF Chaplains’, unpublished paper, held by author.

[44] Douglas M Johnston, ‘We Neglect Religion at Our Peril’, Proceedings 128, no. 1 (2002): 50–52.

[45] Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement’, p. 44.

[46] John Saunders, ‘Deployed Chaplains as Force Multipliers through Religious Engagement’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, July 2014, p. 31.

[47] Stephanie Desmon, ‘Engaging Religious Leaders to Boost COVID-19 Vaccination’, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs website, 2 May 2022, at: https://ccp.jhu.edu/2022/05/02/religious-leaders-covid (accessed 25 October 2022); Melissa Cunningham, ‘Faith Leaders Urged to Spread Word amid Calls for Churches to be Used as Vaccination Hubs’, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 February 2021.

[48] Johnston, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains’, pp. 6, 19.

[49] Emma Kay and David Last, ‘The Spiritual Dimension of Peacekeeping: A Dual Role for the Chaplaincy?’, Peace Research 31, no. 1 (1999): 66–75.

[50] SK Moore, Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace: Religious Leader Engagements in Conflicts and Post-Conflict Environments (Lexington Books, 2012), pp. 135–146.

[51] US Joint Staff, Joint Publication 1-05: Religious Ministry Support for Joint Operations (26 August 1996), p. I-3.

[52] Eric Keller, ‘Beginnings: The Army Chaplaincy Responds to the War on Terrorism’, in Patterson, Military Chaplains in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Beyond, p. 66.

[53] Gladwin, Captains of the Soul, p. 321.

[54] Ramsden, Letters From Timor, p. 95; ‘Chaplain Sees Timor Horror’, Catholic Diocese of the Australian Military Services website, at: https://military.catholic.org.au/chaplain-sees-timor-horror (accessed 1 November 2022); Gladwin, Captains of the Soul, p. 284.

[55] Ramsden, Letters From Timor, p. 132.

[56] Gladwin, Captains of the Soul, p. 284.

[57] Ibid., pp. 284–285.

[58] Lee, Burke and Crayne, ‘Military Chaplains as Peace Builders’, p. 7.

[59] Andrew Richardson and William Westerman, The Struggle for Stability: Australian Peace-Support Operations in Timor-Leste, 2000–2012, Official History of Australian Peacekeeping Operations in East Timor, Volume 2 (forthcoming).

[60] Twomey, ‘Timor Leste 2006 ADF Chaplains’.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Julia Whitwell, ‘Chaplain’s Solomon Islands Mission Ends’, Defence News, 22 June 2022; John Saunders, ‘Religious Leader Engagement: Op Fiji Assist 2020–21’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, 2022, pp. 63–74.

[63] Gladwin, Captains of the Soul, p. 284.

[64] Saunders, ‘Religious Leader Engagement’, p. 71.

[65] George Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders: Lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan’, Peaceworks, no. 56 (2006): 6, 23; Ed Waggoner, ‘Taking Religion Seriously in the U.S. Military: The Chaplaincy as a National Strategic Asset’, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 82, no. 3 (2014): 720; Barry R Baron and Ira C Houck, ‘Religious Advising for Strategic Effect: US Army Chaplains as Change Agents’, Small Wars Journal, 20 May 2013; Seiple, ‘Ready … or Not?’, p. 44; Alexs Thompson, ‘Religious Leader Engagement in Southern Afghanistan’, Joint Force Quarterly, no. 63 (2001), p. 99.

[66] Keller, ‘Beginnings’, p. 66.

[67] Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, p. 8.

[68] Ibid., p. 29.

[69] Thompson, ‘Religious Leader Engagement in Southern Afghanistan’, p. 96.

[70] Ibid., pp. 96–97.

[71] Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, p. 118.

[72] Ibid., p. 113.

[73] Moore, Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace, pp. 147, 209–23; Ants Hawes, John Saunders and Steven Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement: A Chaplain Operational Capability’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, 2018, p. 69.

[74] Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, p. 27.

[75] Ibid., pp. 25–27.

[76] Ibid., p. 38; Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, p. 118.

[77] Lee, Burke and Crayne, ‘Military Chaplains as Peace Builders’, p. 3.

[78] Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, p. 121.

[79] Stephen Brooks, ‘Chaplaincy on Deployment’, Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, 2017, pp. 18–19.

[80] Stuart Yeaman, Afghan Sun: Defence, Diplomacy, Development and the Taliban (Moorooka: Boolarong Press, 2013), p. 171.

[81] Saunders, ‘Deployed Chaplains as Force Multipliers’, pp. 25–30.

[82] Ibid., pp. 29–30.

[83] CR Smith, interview, 1 August 2023, notes held by author.

[84] Saunders, ‘Deployed Chaplains as Force Multipliers’, pp. 29–30.

[85] Johnson to author, email, 2 August 2023, held by author.

[86] Saunders, ‘Deployed Chaplains as Force Multipliers’, p. 31.

[87] Johnson, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains’, p. 30.

[88] Moore, Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace; Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement’, pp. 40–50.

[89] See, for example, Lee, Burke and Crayne, ‘Military Chaplains as Peace Builders’; Baron and Houck, ‘Religious Advising for Strategic Effect’.

[90] Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, p. 121.

[91] Pauletta Otis, ‘Understanding the Role and Influence of U.S. Military Chaplains’, in Patterson, Military Chaplains in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Beyond, p. 33.

[92] Moore, Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace, p. 103; Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement’, p. 48.

[93] Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, pp. 114, 116; Carlson, ‘Cashing in on Religion’s Currency?’, p. 57.

[94] Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, p. 16.

[95] Johnson, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains’, p. 28; Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy, p. 114.

[96] Jacqueline E Whitt, ‘Dangerous Liaisons: The Context and Consequences of Operationalizing Military Chaplains’, Military Review, March-April 2012, p. 60.

[97] Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, pp. 25, 32; Gutkowski and Wilkes, ‘Changing Chaplaincy’, p. 121.

[98] Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, p. 7; Johnson, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains’, p. 30.

[99] The US Army has religious affairs specialists, previously known as chaplain assistants, to support chaplains in their various roles, including ensuring the security and safety of the chaplain in combat situations. Adams, ‘Chaplains as Liaisons with Religious Leaders’, pp. 18–19; Johnson, ‘U.S. Military Chaplains’, p. 30.

[100] Whitt, ‘Dangerous Liaisons’, pp. 61, 63.

[101] US Joint Staff, Joint Guide 1-05: Religious Affairs in Joint Operations (1 February 2018), p. III-6.

[102] Whitt, ‘Dangerous Liaisons’, p. 61.

[103] Moore, ‘Religious Leader Engagement’, p. 44.