The present expedition was formed in contemplation of a long term of service by land and sea alike, and was furnished with ships and soldiers so as to be ready for either as required.

Thucydides, on the Sicilian expedition of 415 BCE[1]

Introduction

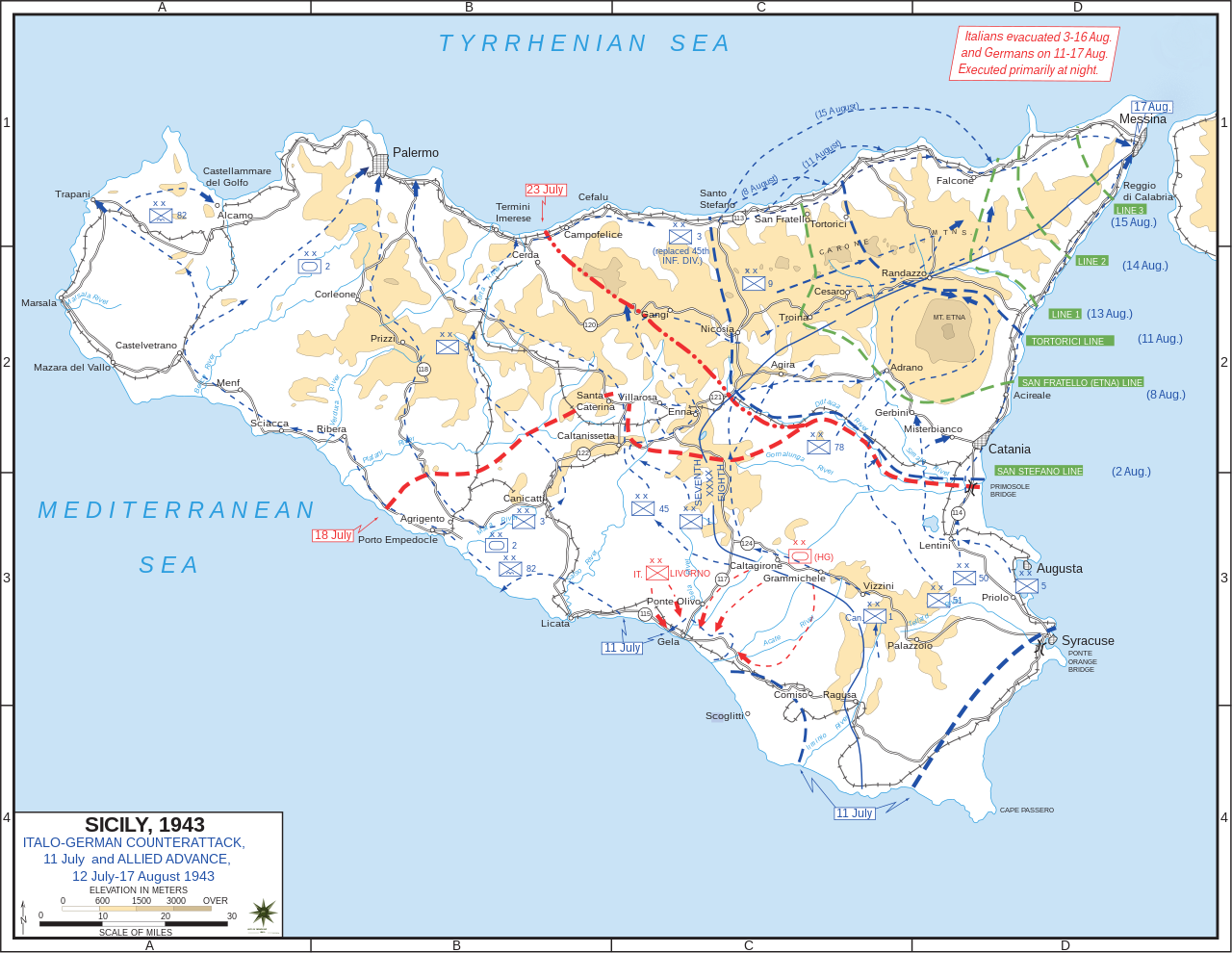

When the Allied forces landed on the island of Sicily in the early hours of 10 July 1943, it was the largest amphibious operation of the war to date. Operation Husky saw US, British and Canadian amphibious forces, preceded by airborne forces, land on the southern and eastern coasts of Sicily as the first step towards a second front to penetrate ‘Fortress Europe’.

There were many lessons learned by the Allies during the Sicily campaign, informing planning before they committed to the invasion of the Italian mainland and then France a year later. However, this article is focused on one small aspect of the campaign: the amphibious operations conducted by the US 7th Army in early August as the US and Commonwealth forces raced to capture Messina. Over the course of two weeks, US forces executed three littoral manoeuvre operations along the north coast of Sicily in attempts to cut off retreating German forces and, in turn, speed the main advance of the 7th Army along the coast road and further inland as they pushed east. The three operations conducted by the US forces feature in descriptions of the larger campaign, but their impact is usually judged to have been minimal. This article is not intended as any sort of revisionist account of why these operations were more significant than has been previously judged by historical study. Rather, it is a short analysis of the first two operations and some lessons that can be taken away. These ‘end runs’, as they were referred to colloquially, were unique operations that had little contemporary parallel in the European theatre of war, and they demonstrated what could be achieved with the use of sea power in the littoral environment.[2]

Two of the three operations will be examined here: the landing to flank the San Stefano defensive line, and the landing near Brolo. The aim is to examine the effect of the operations and the important lessons that can be gleaned from them, rather than to provide a narrative of the battles. Additionally, there are lessons flowing from the use of naval gunfire support (NGS) during these operations, linked to the overall use of NGS during the campaign. There is also a brief exploration of how the US forces utilised the sea for the supply of logistics over the shore after the initial landings, aiding in their advance along the rough terrain of the northern coast. Finally, there is a short word about the Anzio landing of January 1944, arguably a grander but ill-conceived attempt at an ‘end run’ to speed the Allied advance towards Rome in the face of a seemingly similar strategic problem.

Figure 1. Operation Husky, 11 July–17 August 1943 (Source: US Army, West Point)

Sicily Campaign Overview

The Allied invasion of Sicily was a monumental undertaking, with British and Canadian forces landing on the eastern coast and the Americans landing on the southern coast, in the Gulf of Gela. Both forces were preceded by less than successful airborne landings. The US 7th Army was under the command of Lieutenant General George S Patton, and the British 8th Army under General Sir Bernard Montgomery. The two armies were under the overall command of General Harold Alexander.[3] The Allied forces began their landings in the early hours of 10 July 1943, with the British advancing north towards Messina, and the American forces protecting the British left flank while also advancing north-west to capture the important port at Palermo.[4] The goal was to reach Messina and force the Axis units to retreat off the island or, better still, cut them off from evacuation, trap them, and force a surrender. It was a straightforward enough plan, but one that was bedevilled by the unforgiving terrain of Sicily.

One of the greatest issues surrounding the Sicily campaign was this race to Messina. Much has been made of the rivalry between Patton and Montgomery and the contest over who would reach Messina first. There was no doubt in Patton’s mind of the imperative of the US forces reaching Messina ahead of Montgomery. However, it is worth noting the historian Carlo D’Este’s observation that this rivalry was ‘one of the most misunderstood and historically distorted rivalries of the war’.[5] For the strategic context of this paper, it is relevant that Patton saw an imperative to beat the British to Messina to prove the fighting capability of the US Army. This was not merely an issue of personal pride, though that factor cannot be ignored; nor was it only Patton on the American side who wished to see the US Army reach Messina first. Rather, it was the result of months of criticism of US forces and their fighting ability by the British. It even reached the point where the BBC broadcast a story claiming that, while the British and Canadians were engaged in the hard fighting in Sicily, US forces were busy eating grapes and swimming in the sea. Not only did this infuriate Patton, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley and other US commanders in Sicily; it angered the supreme US leader in theatre, General Dwight ‘Ike’ Eisenhower, to the point of writing a letter to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill saying that the BBC were undermining his efforts at creating a unified Anglo-American command in the Mediterranean.[6] In this sense, the race to Messina had a geostrategic, not just a military-strategic, imperative, for the Americans at least.

On the more military side of the equation, the race to Messina was really about cutting off the German and Italian retreat from the island. Matters of pride and glory might be a good plotline in movies and books, but in Sicily the Allies were presented with an opportunity to trap and capture/destroy a substantial force of German and Italian troops on the island. This included the prized Hermann Goering Division, less valuable as a fighting force and more of a potential morale coup if they were to be trapped on the island. Given Allied sea and, to a lesser extent, air control, the only viable evacuation point to the Italian mainland was Messina. This course of action was clear to Patton by 5 August and no doubt added to the sense of haste he injected into operations to reach Messina as soon as possible.[7] This focus is of little surprise since Patton had twice in his career served as divisional intelligence officer (G-2), a posting actively avoided by many other officers, including Bradley. Moreover, his postings as G-2 also instilled within him a greater interest in joint operations and especially amphibious operations.[8] That so many Germans would escape Sicily to continue the fight in Italy was a source of great recrimination in later analyses.[9] The basis for this criticism lies outside the scope of this article, but the key point is that Messina was the primary objective of Allied ground forces in the Sicily campaign. The US 7th Army’s amphibious ‘end run’ operations were designed to speed their advance to Messina.

‘General Patton’s Navy’: the Amphibious ‘End Runs’

Having secured the important port of Palermo on the north-west coast of Sicily on 22 July, Patton was eager to head east for Messina. On 23 July General Alexander gave Patton the go-ahead to push east, setting up the well-known race to Messina between Patton and Montgomery. US forces had two roads they could use: Highway 113, which travelled along the coast; and Highway 120, the inland road. Neither route was easy to navigate, with the coast road cut at many points by streams and ridges running perpendicular to the road and creating good defensive positions, and the inland road being ‘narrow and crooked, with steep grades and sharp turns’.[10] Worse, mountainous terrain divided the two roads, meaning there was little mutual support except via a few roads that ran laterally north–south.[11] Such terrain made the area a defender’s dream and an attacker’s nightmare, a defining feature of the Sicilian campaign, as the British and Canadians advancing up the east coast could also attest.

To support operations along the north coast, on 27 July the US Naval Commander, Vice Admiral Henry Hewitt, created Task Force 88 (TF 88) under the command of Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson. It would, in effect, become ‘Patton’s Navy’, tasked with four missions: defence of Palermo; naval gunfire support to the 7th Army; provision of amphibious vessels for ‘leapfrog’ landings behind enemy lines; and logistics support, providing sealift of supplies and vehicles to ease road and rail congestion.[12] The minute German and Italian naval threat to Palermo did not factor much in TF 88’s tasking over the following three weeks, and so the naval force operated primarily to support the land force. Importantly, Patton had a good relationship with Hewitt. They were on a first-name basis and Patton was willing to defer to Hewitt and the navy over his own staff when it came to naval and landing matters.[13] After the capture of Salerno in late July, Patton even offered Hewitt some captured German staff cars as a gift if the navy could help him reach Messina before Montgomery.[14] This close relationship between the land force and the naval force was crucial to the effectiveness of the landing operations to come.

The approval on 23 July for the 7th Army to move east towards Messina saw concurrent efforts by two US divisions under Bradley’s II Corps. While Major General Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division made the inland push along Highway 120, the advance along Highway 113 fell to Major General Lucian Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division. They faced off against Generalmajor Walter Fries’s 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, supported by Italian units. The road itself was physically in good shape and could carry military traffic both ways. It was, however, very easy to block. Truscott therefore decided to make his main advance further inland across the mountains. It was still difficult terrain that favoured a defender, but with more options for manoeuvre than the coast road, which he would still advance along to keep pressure on the Germans from that direction.[15] Thus, unlike Allen’s advance inland, Truscott could support his main advance with a move along the coast which, in turn, could be supported by amphibious operations. This was a possibility that both Patton and Bradley had noted as early as 30 July and, as indicated, was one of the four roles for which TF 88 had been created.[16] Soon after, Patton determined that this option should be exercised and agreed to Bradley’s request that his II Corps time the landing in coordination with Truscott to allow for an effective link-up between the landing force and 3rd Division’s forces advancing along the coast road. The 7th Army planners selected four landing places behind expected enemy defensive lines in preparation for carrying out an amphibious ‘end run’.[17] The major handicap would be that Admiral Davidson only had enough landing craft to lift one reinforced infantry battalion.[18] Nevertheless, such a force had the potential to cause the Germans trouble as they attempted an orderly withdrawal east towards Messina. It was an eventuality that worried Fries, who knew he could not properly guard against all the landing spots behind his lines and could only ever spare one battalion in reserve against a landing.[19] Unsurprisingly, Fries’s resources would be insufficient to counter the Allies’ superior sea power.

The first ‘end run’ was planned to land just east of the Furiano River in order to flank the German defensive positions at San Fratello. This defensive line had proved tough to crack, and Truscott’s efforts to push through from the inland side made little progress. On 6 August he gave the go-ahead for a landing behind the San Fratello line.[20] The force selected by Truscott was Lieutenant Colonel Lyle Bernard’s 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry, reinforced by two batteries of the 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion and by 3rd Platoon of A Company, 753rd Tank Battalion.[21] Having begun their embarkation after noon on the 6th, Bernard’s force had their loading attacked by four German aircraft. Two planes were shot down, but one of the Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) was damaged. This vessel was critical for the conduct of the operation, so the damage resulted in a postponement of the operation for 24 hours until a replacement vessel could be found.[22] The landing operation was rescheduled for the early morning of 8 August. The incident highlighted a sore spot for the navy operating along the north coast: lack of air support. The US Navy official history is blunt in its assessment: ‘Adequate air cover was never provided to the ships operating along the coast.’[23] As if to punctuate this point, the next day while Bernard’s force once again began its embarkation, German aircraft conducted another attack on the landing vessels. They damaged one LST but not enough to prevent its being hastily repaired and the operation going ahead.[24] It was a close call and highlighted the vulnerability of amphibious units loading (or unloading) on the beach.

The landing force approached the coast undetected and without incident. The first of Bernard’s troops touched down at 0315 and, an hour later, had all been unloaded, including the vehicles. They achieved complete surprise, but the Germans reacted quickly once they discovered the Americans had landed behind their lines. Soon after, Bernard realised that his force had been landed west of the Rosmarino River rather than east of it, but he adapted to the situation quickly.[25] With the attack of Truscott’s forces along the road, the Germans were forced to fight in two directions, trying to breakthrough Bernard’s landing force while holding off the coastal road advance of the US 7th Infantry Regiment. Fighting was fierce, and the Germans counter-attacked Bernard’s force using two Italian Renault R35 and two German Mark IV tanks in an attempt to open the coast road for their withdrawal. However, the field artillery and medium tank platoon neutralised the threat, destroying both Italian tanks and one German tank.[26] Fighting continued into the afternoon, with the 7th Infantry linking up with Bernard’s force and capturing a large number of Italians. All but one company of Germans, however, managed to escape east. The landing itself was successful but the operation failed to cut off the German retreat. Scholarly opinion has assessed that the operation caused the Germans to abandon the San Fratello defensive line earlier than expected but was otherwise of little consequence.[27] Still, the operation was an effective use of Allied sea power, it put pressure on the German withdrawal, and it validated the concept of amphibious ‘end runs’ as a means of injecting some mobility into the American advance against tough German opposition.

General Patton was pleased with the San Fratello operation. He wanted deeper strikes in conjunction with airborne drops, hoping to cut off a sizeable German force, if not the entire 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, still some 120 km from Messina.[28] Facing stiff opposition, Patton was in no mood to continue to slug it out along Highway 113 and so he ordered another amphibious landing to flank the German defensive line at the Naso ridge. Patton ordered Bradley to conduct such an operation on the morning of 10 August but, in a repeat of 6 August, the Luftwaffe attacked TF 88 and sank one of the mission-critical LSTs on 10 August.[29] The operation was rescheduled for the 11th but the plan became complicated when the 15th Infantry did not advance far enough towards the inland position of the Naso ridge. Because of this, combined with the slow advance of the 7th Infantry along the coast, Truscott wanted to delay the landing by another 24 hours rather than risk these linking-up forces being too far away from the landing force to provide support.[30] This led to one of the more controversial incidents of the Sicily campaign, at least in hindsight. Specifically, in various books and histories, and even on screen, Patton and Truscott are recorded as having had it out with one another.[31] With the slower than expected advance of 15th and 7th Infantry, and knowing that Highway 113 was the main route of retreat for the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, Truscott was very concerned the landing force would be isolated for too long without support and not strong enough to stand in the way of the German retreat.[32] By contrast, Patton was insistent that the operation go ahead, a view which caused considerable friction between the two commanders.

With the landing operation confirmed, Bernard’s force began loading on the evening of 10 August. The landing force, consisting of nine landing vessels, covered by the cruiser USS Philadelphia and six destroyers, arrived off the beach in the early hours of 11 August and began their landings near the town of Brolo.[33] Bernard’s infantry battalion was once again supported by medium tanks and combat engineers. An infantry company went in first, followed by the engineers, tasked with clearing the beach of any defences and securing the beachhead for the armour and remaining infantry companies. The fourth wave saw two batteries of self-propelled artillery land and, along with the tanks, provided the main organic fire support elements for the landing force.[34] The landings went off without major issue and the entire landing force made it ashore in under two hours, without resistance or loss.[35] Again, it did not take long for the Germans to respond. Indeed General Fries had stationed a force in and around the town of Brolo to guard against such a landing, having been worried about a repeat of the San Fratello landings.[36] The local German commander, Colonel Fritz Polack, informed General Fries of the situation, who found it alarming, seeing the real possibility that the division’s line of retreat could be cut off. In response, Fries ordered Colonel Polack to counterattack the American landing force.[37] So alarmed was he that he pulled forces off the main defensive line of the Naso ridge and had them attack east to try to clear Bernard’s force from his main line of retreat.[38] Clearly the US landing had realised one of Fries’s fears: being outmanoeuvred via the sea.

Of critical importance to the support of the landing force was the provision of NGS. The light cruiser Philadelphia was armed with fifteen 6-inch guns and eight 5-inch guns, representing the bulk of the afloat firepower, supported initially by six destroyers. The NGS provided was accurate and crucial in supporting the forces ashore. The weight of fire from the ships was enormous, with Philadelphia alone expending 1,062 6-inch shells throughout the day.[39] However, poor communications between ship and shore meant that, on three occasions, the ships departed the landing zone and had to be recalled by 7th Army HQ soon after each departure.[40] The main factor was communication, which was inconsistent and constantly dropped out. Combined with patchy and inconsistent air cover, this meant that the ships were vulnerable to air attack and unwilling to stay on the scene when they ceased receiving calls for fire. Without communication with the troops ashore, the ships were unable to fire on any targets and were thus merely targets for German air attack.[41] Unwilling to wait around for a re-establishment of communication while under threat of air attack, the ships were naturally inclined to retire.

Nevertheless, the NGS provided was critical in supporting the landing force. Even just the appearance of the friendly warships boosted the morale of the troops ashore.[42] The first time on station saw Philadelphia lay accurate fire on Fries’s eastbound troop convoy, destroying several vehicles and scattering the infantry.[43] The first recall of the ships was a result of the Germans massing for a counterattack with two infantry companies and several tanks. More worryingly, Bernard’s request for support surprised Truscott, who was not aware that the TF 88 warships had departed the scene.[44] Thankfully, TF 88’s liaison officer in 7th Army HQ received the urgent request for fire support, and Admiral Davidson sent the cruiser and two destroyers back to Brolo at 31 knots.[45] The arrival of the three ships coincided with a friendly air strike by 12 A-36s, and this combined firepower helped break up the German attack.[46] During the final engagement, after TF 88’s second recall, one of the officers from the shore party was forced to commandeer a DUKW to physically go out to the ships in order to establish contact. Fortuitously, this effort was successful, and the cruiser once again went to work. This included an interruption as eight German aircraft attacked the ships. The Luftwaffe aircraft caused no damage but lost seven of their number to the ships’ anti-aircraft fire and Allied air cover.[47] Had it not been for the constant breakdowns in communication between ship and shore, and had more friendly air cover been available, the warships could have remained on station the whole day and provided or been ready to provide constant fire support.

Despite the support provided by the Allies’ naval and, to a lesser extent, air forces, the Germans were still able to put great pressure on Bernard’s small force. As the afternoon turned to evening, Bernard had decided to consolidate his forces on Monte Cipolla and await relief. The 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment took control of the highway and opened an escape route east, and was gone by the early hours of 12 August.[48] With the Germans speeding east towards Messina and evacuation from Sicily, a third landing operation was planned and then executed on 16 August. It was to no effect, however, as the US forces advancing along the coast had already overrun the landing zone and so the Regimental Combat Team (RCT) assigned to the landing was met by friendly forces.[49] Soon after this the US forces reached Messina, with the German forces having successfully evacuated across the Strait of Messina to mainland Italy.

Analyses of the Brolo landing operation see it as of minor consequence, no doubt speeding the German withdrawal and, as seen above, causing German high command some serious anxiety. The landing did not, however, cut off the German retreat, and it inflicted modest but not disproportionate casualties.[50] Patton’s push for the landing operations caused severe tension with both Truscott and the reluctant Bradley, who never liked the idea of the amphibious operations and preferred a slow and steady slog against the German forces. The question then is what would have made these operations more effective, especially the Brolo landing, which did cause the Germans much concern. More than anything, the main lesson agreed on by modern analyses is that the landing force was too small. A reinforced infantry battalion did not have the mass to stop the retreating Germans and thus allowed them to punch through the thin cordon blocking their escape route. Modern scholars agree that a larger force, such as an RCT, would have had a far higher chance of success.[51] It is hard to disagree with this conclusion and it seems clear that a larger landing force would have made the difference. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that, although the third and final operation had nil impact on the campaign, the fact that it consisted of an RCT helps demonstrate that this lesson had been learned. More importantly, the decision to land a larger force was only made because the navy could provide more landing craft at that time. The reason why the San Fratello and Brolo landings were conducted by a reinforced infantry battalion was precisely because that was the largest force that could be lifted by the naval forces available. Notwithstanding this restriction, the core lesson remains. To be effective, such littoral manoeuvre operations require sufficient weight of numbers. In the Sicily examples, this would have been a larger force able to withstand German attempts at a breakthrough.

Figure 2. Lieutenant Colonel Lyle Bernard (right) and Lieutenant General George S Patton (left) near Brolo, 12 or 13 August 1943 (Source: US National Archives and Records Administration, NWDNS-111-SC-246532).

The second core lesson from these littoral manoeuvre operations is the criticality of support for landing forces, during and after landing operations. This includes organic fire support, such as armour and artillery, as well as both naval and air support. A platoon of tanks was included in both landing forces, and they proved invaluable in supporting the infantry units, especially during the San Fratello operation, where they helped neutralise German and Italian armour. Despite possessing some organic artillery support, two batteries of self-propelled guns, the landing force at Brolo was nevertheless reliant on fire support provided by the cruiser Philadelphia and the accompanying destroyers. The self-propelled guns took time to position, and the nature of the terrain limited their movement and placement. Bernard’s 81 mm mortars were extremely effective but suffered from the need to be supplied from the beach via mule train over the mountainous terrain. Finally, the landing force was far enough behind the enemy lines that it was at the very extreme range of the 155 mm guns of 3rd Division. These guns could fire on the Germans in Brolo, but the extreme range affected their accuracy.[52] German air attacks focused on the naval ships rather than Bernard’s ground force, and so the issue of organic anti-aircraft support—or a lack thereof—does not come up. Still, it would be another critical factor to consider, given the force was not operating in an environment of friendly air control.

The lack of sufficient friendly air support had two key effects on the landing operations. Firstly, before the operations had even begun, enemy air interdiction damaged the US amphibious vessels at the embarkation zone, causing delays to the first operation and almost delaying the second. The US forces were perhaps lucky that German air power had been so degraded over the previous few weeks and could not mass larger attacks. Secondly, the air attacks on the supporting warships during the Brolo landing caused the ships to break off from providing critical NGS to the troops ashore as they had to defend themselves from the air attack. Again, the US was fortunate that the German air forces could not muster a large enough force to seriously threaten the warships—not to say that it was not a dangerous situation. This is in addition to the obvious impact of poor air support which delivered insufficient sorties to support the forces ashore. Air support was promised by XII Air Support Command, but it could not give timings or even number of planes. Two sorties of 12 A-36s eventually materialised at an important juncture and provided good support. Further air support was promised but again with no detail.[53] A third sortie did eventuate, but the seven A-36s had poor situational awareness and two bombs landed on Bernard’s command post, causing 19 casualties and knocking out several howitzers.[54] This deficiency once again highlights the importance of having reliable communications with all supporting forces.

All these lessons on ‘amphibious attacks’ are neatly summarised in 7th Army’s assessment of the campaign. The Deputy Commander, Major General Geoffrey Keyes, wrote to Patton:

When a parallel flank commanded by the Navy exists, it is very important to use amphibious attacks in rear of the enemy’s position. These amphibious attacks should be in a strength at least equivalent to a reinforced combat team, because such a force can land further in rear of the enemy and can be self-sustaining for a period of days. Navy gunfire support is vital.[55]

The ‘end run’ operations were imaginative and well planned, and the landing phase was executed almost without fault. The ‘almost’ refers to the San Fratello landing force being put ashore on the wrong side of the Rosmarino River. Landing on the wrong beach is always a risk in amphibious operations, but in this case, it had minimal effect on the operation’s outcome, largely due to the quick reaction of Bernard once he realised they were in the wrong position. Still, it proved to be a valuable lesson for all the force involved, at sea and ashore. Despite their limited effect on the campaign, these operations proved a concept and demonstrated the effect that could be had by solid navy–army ‘joint’ operations in the littoral.

The British Advance

The efficacy of US amphibious ‘end run’ operations may be debatable but they provide a useful case study. On the other side of Sicily however, there were no such operations. General Montgomery steadfastly refused to consider conducting similar operations as his forces advanced northwards towards Messina. The most scathing critique of the British non-approach to conducting similar amphibious operations came from the Royal Navy’s own Admiral Andrew Cunningham. Both the British and US official naval histories of the war quote him as saying:

There were doubtless sound military reasons for making no use of this, what to me appeared, priceless asset of sea power, and flexibility of manoeuvre; but it is worth consideration for future occasions whether much time and costly fighting could not be saved by even minor flank attacks, which must necessarily be unsettling to the enemy. It must always be for the General to decide. The Navy only provide the means, and advise on the practicability from the naval angle of the projected operation. It may be that, had I pressed my views more strongly, more could have been done.[56]

Even more cutting is his brief comment on the American ‘end run’ operations: ‘a striking example of the proper use of sea power’.[57] While this analysis of the US operations dismissed them as having been of limited value operationally, the overall opinion of contemporaries seems to be that they were worth the effort. Leaving aside the fraught issue of motivation in the race to Messina, these ‘end runs’ were seen by the Allies, and the Germans, as an effective use of sea power. The Royal Navy Official Historian Stephen Roskill came to the careful conclusion that a well-planned and well-resourced landing operation had the potential to cut off the German retreat to Messina.[58] The landings that were carried out by the US forces demonstrated the potential of using the sea as an operational manoeuvre space.

Support Operations: Naval Gunfire Support and Logistics over the Shore

There are two further maritime aspects of the Sicilian campaign worth mentioning in parallel to the manoeuvre operations. The first, covered partially above, is the provision of NGS, and the second is the provision of logistics over the shore.

NGS played a crucial role during the initial US 7th Army landings in the Gulf of Gela. Detailed analysis of the landings at Gela and subsequent battles are outside the scope of this article, but a summary is needed here. Essentially, the NGS provided by cruisers and destroyers in the Gulf of Gela was crucial in blunting the German and Italian counterattacks on D-Day and D+1. The fire support was accurate, timely and effective, including against German and Italian armour.[59] Patton praised the NGS as having been ‘outstanding’ and noted that it had been effective even at night, landing on target within the third salvo.[60] Altogether, on 10 July (D-Day) four warships fired 572 rounds and on 11 July (D+1) 10 ships fired 3,199 rounds—the destroyer USS Beatty alone firing 799 rounds of 5-inch ammunition.[61] The effectiveness of the NGS during the initial landings erased any doubt in the minds of Patton and the other army commanders that the navy could provide effective fires ashore. After the capture of Palermo and the US drive east along highways 113 and 120, US warships continued to provide NGS, both in support of troops ashore and against fixed defensive positions.[62] German movement along Highway 113 itself was hampered by Davidson’s warships conducting NGS, being more effective than heavy artillery or air strikes. From Santo Stefano east to Cape Orlando, Davidson’s ships hampered Fries’s withdrawal with NGS.[63] Naval firepower had an impact not only in direct support of troops ashore but also independently in hitting targets of opportunity along the ill-defended coast.

Figure 3. US Navy cruiser USS Brooklyn (CL-40) providing naval gunfire support to troops ashore during the Husky landings, 10 July 1943. USS Philadelphia was of the same class of ship (Brooklyn class) (Source: US Naval History and Heritage Command, ID 80-G-42522).

On the British side, NGS played an important role in supporting the initial landings, but less so during the rest of the campaign. The Royal Navy (RN) forces were equipped with monitors armed with 15-inch guns, capable of delivering devastating fire. During the British and Canadian advances there were approximately 200 calls for fire answered by RN ships.[64] NGS was used to support the advance north towards Messina, but the results seem to have been disappointing, even with the big guns of the monitors.[65] In his history, SE Morison is not complimentary of the British NGS effort, finding it to have been ‘not impressive’.[66] To be fair, he also acknowledges that the US had better opportunities to prove their NGS capability.[67] Perhaps a key difference between the US and RN operations is the absence of landings like the US ‘end runs’. These landings forced the Germans to concentrate and left them open to the guns of the fleet. The use of NGS during the campaign is a major focus of Morison’s official history volume, and indeed is described by him as a secondary theme of the book. The revolution in technology and tactics that allowed for more accurate and responsive NGS caused him to remark: ‘Thus the Navy acquired a new function in amphibious warfare; and its development is one of the fascinating and significant things related to this volume.’[68] This represented an important step forward for combined land-sea operations in the littoral.

Had the efficacy of the new NGS capability been apparent beforehand, perhaps the Allied naval forces would have been less reluctant to aggressively patrol the Strait of Messina. Conventional wisdom was derived from the oft-quoted line by Admiral Horatio Nelson that a ship was a fool to fight a fort. James Holland refers to this pithy saying when concluding that the Allies would have been foolish to push into the Strait of Messina, guarded by hundreds of shore batteries.[69] Interestingly, Morison notes at the very beginning of his volume on the campaign: ‘I cannot recall that enemy coastal batteries in the Mediterranean registered a hit on any Allied naval vessel larger than an LST, or more than a mile from shore.’[70] In this respect, the Sicily campaign is one more chapter in the war of concepts and doctrine on whether ships or shore-based systems have the upper hand. As in most complex issues of maritime operations, the answer no doubt lies in the context of the situation, rather than bold assertions of technological supremacy or obsolescence.

Less glamorous, but no less important, was the use of naval assets for logistics support over the shore during the American advance east towards Messina. Once a firm foothold had been established on the island, the movement of supplies from the beachhead and, once opened, the ports became an important logistical effort. Although Palermo was open to deep-draught vessels and thus a great volume of supplies, there was still the issue of getting said supplies to the front. As outlined above, the terrible state of road and rail transportation made this very difficult. By employing smaller naval craft to lift supplies along the coast onto beaches much closer to the front, advancing US forces were kept supplied and in the fight. This enabled US forces to continually place pressure on the retreating Germans. So critical was this enabler that Eisenhower, in his ‘Commander-in-Chief’s Dispatch’ on the Sicilian campaign, wrote that ‘the movement of essential supplies by sea direct to the advancing armies materially hastened the end of the campaign’.[71] Stephen Roskill made the observation that a key enabler of success in the operation was the introduction of the new American capability, the DUKW. This new capability enabled the Allied forces to sustain operations over the beach instead of relying on the early capture of a port.[72] While it could never match the output of a port facility, it nevertheless enabled better logistics over the shore, including in the above use of resupply along the coast.

Not just supplies but whole combat formations were also moved using sealift. In preparation for the first amphibious operation near San Fratello, on 4 August the 7th RCT and attached corps artillery was loaded onto navy landing craft and shuttled east along the coast for pre-positioning.[73] As the Germans continued their withdrawal towards Messina they ensured the destruction of the roads and bridges behind them to slow the US advance. On 13 August as the US forces advanced past Cape Calava they used LCTs to load infantry and artillery and go around the damaged road at the Calava tunnel—damage that took 24 hours to repair.[74] Thus the US forces were able to keep up an advance despite the damaged road.

Sicilian Legacy—Anzio, the Grand ‘End Run’?

A natural question arising from a study of the Sicily amphibious operations is how much they influenced Operation Shingle, the landing at Anzio on 22 January 1944. On the face of it, the Allies were in a similar position. Harsh terrain that heavily favoured the defender was slowing the Allied advance north through mainland Italy, the enemy positions were exposed to a flanking attack from the sea, and the Allies maintained sea control in the Italian littoral. In September–October 1943, Allied thinking indeed turned towards an amphibious operation as a potential means of breaking through the German defences at the ‘Gustav Line’ and continuing the advance towards Rome.[75] In the words of Morison, ‘Why not exploit their sea power to effect one or more 'end runs'—amphibious landings behind the enemy’s right flank, to divert his strength and cut off his routes from Germany.’[76] General Alexander’s thinking clearly illustrates that the Anzio landing was designed to pull German forces away from their main defensive line and allow for an Allied breakthrough.[77] Planning for such an operation would be constantly overshadowed by the demands of operations Overlord and Anvil, the two amphibious operations to invade northern and southern France, respectively. In a similar vein to the Sicilian operations, the key limiting factor in these (and any) amphibious operations was the availability of suitable vessels and landing craft for an initial lodgement and subsequent sustainment. Unlike in the Sicilian operations, a meet-up between the landing force and the relief force was not expected to occur on the same day, so more robust logistics would be required at Anzio.

Nevertheless, if the rationale behind Anzio seemed to follow that of the 7th Army’s Sicilian manoeuvres of early August 1943, it was only in the broadest sense and without proper consideration of lessons that should have been learned. In the first place, German forces in Sicily had been withdrawing and the idea of the operations had been to cut off retreating Germans. On the mainland, Anzio was devised as a means of outflanking a static defensive line, against a strong German force that had significant reserves in place.[78] More importantly, during the Brolo operation both Truscott and Bradley had been hesitant to go ahead with the landing because they considered that the main force advance along the coast was too far from the beachhead, putting the amphibious force at risk of being overwhelmed. At Anzio, this main body (US 5th Army) was much further from the beachhead and was essentially stalled in its own advance. It was for this reason that Morison’s final judgement was that Operation Shingle was ‘doomed by its very nature to drag along for months’.[79] It is hard to dispute his contention that such an operation should have been conducted closer to the 5th Army’s stalled front line where the two fronts would have been mutually supporting.[80] After the Anzio advance stalled, the British were pushing for postponement or cancellation of Anvil because they saw the need to reserve forces and amphibious assets—enough to lift one entire division—for further ‘end runs’.[81] Indeed, the Germans did not view Anzio as much connected tactically to the main Allied advance up the Italian mainland. The Head of Operations staff at Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), General Alfred Jodl, considered it an independent operation, likely one in a series forcing the Germans to disperse forces to different fronts and weaken their reserves before the long awaited cross-channel invasion.[82] This might have misread Allied intent, but practically speaking it was fairly accurate.

The second point worth highlighting is that, just as with the two Sicily landings, the Anzio operation was not of sufficient force size to have a decisive impact. It may have seen two divisions landing rather than a reinforced infantry battalion, but the principle of concentration of force remained relevant. In the face of ample German reserves, the landing force was simply not large enough to do more than hold the beachhead and could not be sustained or reinforced rapidly enough to exploit the beachhead. The force was too small and too far away to put pressure on the Gustav Line, and in this sense the Germans seem correct in having judged the Anzio landing as a separate operation to the main Allied push, even if that was not the Allied intent.

In the end, while planning for Anzio may have had the Sicilian ‘end runs’ in mind as a means of breaking a defensive line, it was not so simple in practice. Anzio was not, and could not be under the circumstances, a grand style ‘end run’ like those conducted in Sicily. The 7th Army’s amphibious operations were excellent examples, however imperfect, of the use of the maritime environment as an operational manoeuvre space. Good strategy is not simply a matter of scaling up effective operations.

Conclusion

The Sicily campaign of July–August 1943 bears many lessons for those wishing to delve into amphibious operations and questions of littoral manoeuvre. This article has focused on one small aspect of the overall campaign: the amphibious ‘end runs’ conducted by the US 7th Army along the north coast of Sicily. The landings at San Fratello and Brolo sped up the German retreat and had the potential to cut off German formations.

In the end, the forces landed were too small to effectively block the German retreat. This is the first lesson: that such operations need a body of mass sufficient to hold up a retreating enemy and prevent them breaking through a cordon. In the Sicily case, an infantry battalion reinforced by self-propelled guns and a single tank platoon was insufficient for this task. By all accounts, a larger RCT would have provided the required combat power.

The second lesson is the importance of navy–army–air force cooperation. Aside from the obvious lesson that one must have at least working sea control, this in itself is not enough to guarantee success. A landing force behind enemy lines, or even isolated from other friendly land forces, is vulnerable and, even with organic fire support, still requires external fires. This means naval and air support, and it means solid communications between ground and sea–air forces. Without reliable communication between ships and shore, the supporting warships had to break contact several times lest their bombardments hit friendly forces. In the two examples above, the Allied forces did not have air superiority. Relatively small German air attacks were able to twice disrupt naval forces embarking ground forces, causing one to delay and almost delaying another. During the operations small German air forces were still able to threaten the beachhead and supporting naval units. In the latter case, this necessitated the ships breaking off from the provision of vital NGS support in order to defend themselves from the air attack. That the promised Allied air support came with no detail as to timings or sortie size was of great concern to the land commanders. Even worse, with such poor communication between ground and air forces, unnecessary casualties were suffered by the ground forces on the receiving end of ‘friendly fire’ from the attack aircraft.

Two highlights stand out from these supporting operations. The first is the potential for naval units to provide support ashore, in this case through accurate, timely and effective NGS. Moreover, while a lack of friendly air support saw the ships forced to break off supporting fires, it did at least ensure these hostile aircraft did not attack the forces ashore. The second noteworthy positive was the use of maritime assets for resupply of ground forces. The Sicilian terrain was incredibly rugged and not conducive to moving large amounts of stores from supply areas to the front. Allied sea control allowed for the use of amphibious craft to deliver supples along the coast close to where they were needed. Oft overlooked, the criticality of logistics needs to be constantly reinforced, and the potential of maritime space to provide an avenue of resupply highlighted.

The Allied campaign in Sicily was a success, despite the large-scale evacuation of German forces. The two amphibious ‘end run’ operations explored in this article were a small but notable part of the campaign. They were an excellent example of how proper use of the sea grants options to ground forces. They remain a prime example of using the sea as an operational manoeuvre space to gain advantage over an adversary.

About the Author

Dr John Nash is an Academic Research Officer at the Australian Army Research Centre. Previously he was a researcher at the Australian War Memorial for The Official History of Australian Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Australian Peacekeeping Operations in East Timor. He was awarded a PhD from the Australian National University in July 2019. He is also a Lieutenant in the Royal Australian Naval Reserve, having completed nine years’ fulltime and seven years’ reserve service as a Maritime Warfare Officer. He was the inaugural winner of The McKenzie Prize for the Australian Naval Institute and Chief of Navy Essay Competition – Open Division, 2019. His most recent publication is Rulers of the Sea Maritime Strategy and Sea Power in Ancient Greece, 550–321 BCE, Volume 8 in the series ‘De Gruyter Studies in Military History’. Other publications include an article in the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (March-April 2022) and the US Naval War College Review (Winter 2018, Vol.71).

Endnotes

[1] Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 6.31.3.

[2] Space precludes a comparison with the Pacific theatre of war and the many amphibious operations conducted there.

[3] For a comprehensive order of battle of sea, land, and air forces for the Allies, Italians, and Germans, see James Holland, Sicily ’43: The First Assault on Fortress Europe (London: Penguin Random House, 2020), pp. 603–632.

[4] Only after Patton pushed Alexander for this course of action.

[5] Carlo D’Este, Bitter Victory: The Battle for Sicily, 1943 (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1988), p. 445.

[6] For more on this, see D’Este, Bitter Victory, pp. 449–450.

[7] Lieutenant General George Patton, ‘Summary of Operations: The Operation’, in Report of Operations of the United States 7th Army in the Sicilian campaign, 10 July – 17 Aug 1943 (1943), p. B-16. Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, Special 940.514273 U56ro, at: cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/3295.

[8] Bradley calling those who ended up assigned to intelligence as ‘misfits’ and the G-2 as a ‘dumping ground’ and saying, ‘I recall how scrupulously I avoided the branding that came with an intelligence assignment in my own career’. James Kelly Morningstar, Patton’s Way: A Radical Theory of War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017), p. 126.

[9] Witness the title of one of the most influential works on the campaign, Carlo D’Este’s Bitter Victory. He begins his brutal analysis by saying: ‘That Alexander never understood the consequences of the campaign he had so ineptly led typified the unsatisfactory ending to Operation Husky.’ See D’Este, Bitter Victory, pp. 523–564. More understanding of the Allied concerns that held up a more vigorous naval operation to block the Strait of Messina are the US and RN histories, respectively: Samuel Eliot Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio January 1943 – June 1944. History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume Nine (Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 1954), pp. 220–221; SW Roskill, The War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3, Part 1. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1960), pp. 146–152. James Holland is far kinder in his conclusion, perhaps overly so given the ample opportunities the Allies had to do something more to interdict the German retreat across the strait. See Holland, Sicily ’43, pp. 577–582. Holland is certainly correct in identifying that overall Husky was a success and did lead to more effective Allied operations afterwards.

[10] Albert N Garland and Howard McGaw Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy. The Mediterranean Theater of Operations. United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1993), p. 309.

[11] Ibid., pp. 309–311.

[12] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 191.

[13] They addressed each other as ‘Kent’ and ‘Georgie’ in written correspondence. Rick Atkinson, The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944 (London: Abacus, 2013), pp. 31, 42–43.

[14] Ibid., p. 143.

[15] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 348.

[16] Ibid., pp. 348–349.

[17] Ibid., p. 349.

[18] Ibid., p. 349.

[19] Ibid., p. 357.

[20] Ibid., p. 360.

[21] Ibid., p. 352; Lt Colonel G Felber, ‘After Action Report 753rd Tank Battalion’, Operations of 753rd Tank Battalion (M), in Sicilian Campaign (August 1943), p. 4. Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, at: cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/3506.

[22] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 360.

[23] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 192.

[24] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 361–362.

[25] Ibid., p. 363.

[26] Ibid., p. 363.

[27] Ibid., pp. 363–367. See also D’Este, Bitter Victory, pp. 477–479.

[28] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 380.

[29] Ibid., pp. 388–389.

[30] Ibid., pp. 389–390.

[31] ‘Object of bitter American controversy’ in D’Este’s words: D’Este, Bitter Victory, pp. 479–480. The incident featured prominently in the 1970 movie Patton, down to Patton’s quoting of Fredrick the Great in urging Truscott ‘L’audace, l’audace, toujours l’audace’ (audacity, audacity, always audacity).

[32] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 389–391.

[33] One LST, two LCIs and six LCTs carrying LCVPs and DUKWs. Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 192.

[34] This tank platoon was a different one from that involved in the San Fratello landing a few days earlier, this time from Company B of the 753rd Tank Battalion. See Felber, ‘After Action Report 753rd Tank Battalion’, p. 4; Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 393–394.

[35] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 394–396.

[36] Ibid., p. 393.

[37] Ibid., pp. 396–397.

[38] Ibid., p. 398.

[39] The destroyers were each armed with four 5-inch guns. Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 403, n.6.

[40] Departed first time 0930 after all pre-arranged targets had been hit and no more calls came in from ashore; recalled at 1200 and arrived back on station 1400. Departed again at 1500 and recalled again an hour later, arriving sometime before 1700. Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, pp. 203–204. The army account has the ships leaving the first time at 1025: Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 399.

[41] See Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, pp. 203–205.

[42] D’Este, Bitter Victory, p. 481.

[43] ‘On station’ refers to the ship positioned in its assigned area of operations prepared to conduct duty, in this case naval gunfire support. Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 398–399.

[44] Ibid., pp. 400–401.

[45] Destroyers Ludlow and Bristol. Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 203; Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 401.

[46] The A-36 was the ground attack version of the more famous P-51 Mustang. Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 401.

[47] Five claimed by Philadelphia, and one each credited to Ludlow and a US Army fighter plane. Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 204; Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 403.

[48] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 403–404.

[49] Ibid., pp. 407–408, 413–415.

[50] Suffering approximately the same as the US 3rd Division during the attack. Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 405.

[51] D’Este, Bitter Victory, p. 481; Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 404–405; Atkinson, The Day of Battle, p. 162; Holland, Sicily ’43, p. 568.

[52] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, pp. 400–401.

[53] Ibid., pp. 401–402.

[54] Ibid., p. 403.

[55] Major General G Keyes to Lieutenant General George Patton, ‘Summary of Operations: Lessons Learned’, Report of Operations of the United States 7th Army in the Sicilian campaign, 10 July – 17 Aug 1943 (1943), p. C-9. Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, Special 940.514273 U56ro, at: cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/3295.

[56] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, pp. 206–207; Roskill, The War at Sea 1939–1945, pp. 142–143.

[57] Craig Symonds, World War II at Sea: A Global History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 441.

[58] Roskill, The War at Sea 1939–1945, p. 152.

[59] See D’Este, Bitter Victory, pp. 279–302; Atkinson, The Day of Battle, pp. 102–103.

[60] George S Patton, War as I Knew It (New York: Bantam Books, 1980), p. 57.

[61] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 113.

[62] Ibid., p. 197.

[63] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, p. 352.

[64] Roskill, The War at Sea 1939–1945, p. 138.

[65] Ibid., p. 143.

[66] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 207.

[67] Ibid., p. 222.

[68] Ibid., p. xi. While he is writing a volume on the US Navy, given Morison’s wide sweep of the naval war he certainly could be taken to mean that all navies now had a new function providing NGS during amphibious operations.

[69] Holland, Sicily ’43, p. 572. He does observe that Nelson did not listen to his own advice, attacking the heavily fortified city of Copenhagen.

[70] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, pp. xi–xii.

[71] General Dwight D Eisenhower, ‘Allied Force Headquarters. Commander-in-Chief’s Dispatch, Sicilian Campaign, 1943’ (1943), p. 32. Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, N13457, at: cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/5501.

[72] Roskill, The War at Sea 1939–1945, p. 115.

[73] Not all at once, noting the above point that there were insufficient LSTs to lift an RCT in one movement at this time. Patton, ‘Summary of Operations: The Operation’, p. B-16.

[74] Ibid., p. B-20.

[75] For a comprehensive overview of the discussions and planning that followed, see Martin Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino. The Mediterranean Theater of Operations. United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1993), pp. 235–248, 293–304.

[76] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 317.

[77] This was also clear in the thinking of Commander 5th US Army, Lieutenant General Mark Clark. CJC Molony, The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume 5: The Campaign in Sicily, 1943 and the Campaign in Italy, 3rd September 1943 to 31st March 1944. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1973), pp. 600, 602.

[78] Allied intelligence itself was reporting that the Germans had two divisions near Rome, a mere 30 km away, a division within three days’ travel time, and another two in northern Italy that could arrive at the beachhead within two weeks. Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino, pp. 35–54.

[79] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 380. Alexander even asked for a new commander, ‘a thruster like George Patton’, to take charge at Anzio and help push the attack along. Martin Blumenson, Patton: The Man Behind the Legend, 1885–1945 (New York: William Morrow, 1985), p. 220.

[80] Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 381.

[81] Operation Anvil was later renamed Operation Dragoon. Gordon A Harrison, Cross-Channel Attack. The European Theater of Operations. United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1993), p. 169; Molony, The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and the Campaign in Italy, 3rd September 1943 to 31st March 1944, pp. 844–845.

[82] OKW technically was the Armed Forces High Command, but by 1944 in practice was the command responsible for the war outside of the Eastern Front. Forrest C Pogue, The Supreme Command. The European Theater of Operations. United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1989), pp. 175–176; Harrison, Cross-Channel Attack, p. 232; Molony, The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and the Campaign in Italy, 3rd September 1943 to 31st March 1944, p. 621.