A Historical and Strategic Perspective

Speech to the Chief of Army Symposium 2023, Perth Convention Centre, 30 August 2023

[Editorial note: This speech has been edited and condensed for clarity.]

To help focus our topic today, let us first consider my favourite map. If you haven’t seen it before, it is the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) planning map centred on Darwin, but spun 45 degrees (Figure 1). It gives you a sense of Australia hanging off Asia, and what Indonesia’s President, Joko Widodo, called the maritime fulcrum. When you think about the left-hand side and the right, you’ve got the Indo and the Pacific. And this is where I’m going to start.

Figure 1. RAAF Planning Map (Source: reproduced by courtesy of the author).

My Army career and my academic writing have informed my opinions. My most recent publication is Revealing Secrets: an Unofficial History of Australian Signals Intelligence and the Advent of Cyber, and I also have a chapter in Craig Stockings’ book An Army of Influence, from which I’ll derive some of the points covered in this talk. An opinion I hold firmly, and that I teach my university students, is that—when you are talking to busy people, commanders and executives—it’s important to deliver the bottom line up front (BLUF). So here’s the BLUF for this presentation.

Government has expectations and determinants for the use of military force abroad. These are proximity and necessity, alliance management and risk tolerance. The closer to the Australian shore you get, the greater the likely force contribution, the greater the risk/casualty tolerance, and the greater the neighbourhood consequences too. Moreover, the closer you are to Australia, the greater the importance of our intellectual investment in this space, and the significance of cultural, linguistic, and historical understanding. Also relevant is the allied expectation of Australian primacy within our region. Conversely, the further away from Australia, the lesser influence these factors exert.

So there is a dialectic in Australia’s consciousness of geography and history. Our history was as essentially transplanted from Anglo-Europeans, and our geography is on the edge of Asia. Strategically we have a dialectic of defence of Australia, defence of the region, and alliance priorities. I expand on these points in books including Strategic Cousins, Australian and Canadian Expeditionary Forces and the British and American Empires; The Australian Army from Whitlam to Howard; and East Timor Intervention. Using historical examples as a basis for analysis, these publications discuss in some depth the key expectation determinants for the Australian Government when we think about engagement in the region.

When considering what government expects, there are two categories of operations in which the military may be involved. First are operations of choice, and Australia has been involved in those for the last 20 years or so in niche wars such as in Iraq and Afghanistan. Australia’s involvement in these conflicts is briefly surveyed in Niche Wars, which is available from the ANU Press via free download. Operations of choice tend to be conducted far away from our shores and are not waged against a near or peer competitor. As such, Australia is able to make a discrete contribution that is intimately supported by reach-back to national agencies. This level of assistance is achievable because we have only a relatively small joint task force doing the job, so forces can get gilt-edged support. And we have few, if any, casualties. Indeed, when you think about the last 20 years or so, Australian casualties have numbered around 40. And that is actually a pretty good ratio—right?

The second category of military operations are the so-called operations of necessity, which occur closer to home. They are likely to be waged against a peer—or a near peer—competitor that probably has precision-guided munitions, sophisticated intelligence surveillance target acquisition reconnaissance, and air assets. Such a threat warrants a full spectrum, all-arms ADF capability response that is potentially cyber heavy. Despite the high-threat nature of these types of operations, national reach-back facilities will likely be patchy. Why? Because every Tom, Dick and Harry will want some of it: Army, Navy and Air Force. Such operations are also associated with a higher casualty tolerance. And I say higher casualty tolerance because—as we wrote about in the book East Timor Intervention—when John Howard was contemplating the prospect of deploying forces to East Timor, it was with the possibility of significant casualties in mind. He bore that risk on the chin, knowing that it was a risk that had to be managed, but one that Australia was prepared to tolerate. So there you have my BLUF—okay? These are the government expectation determinants, and the capability (or capabilities) that it expects the ADF to deliver, both far away and closer to shore.

I would argue that this a fairly strong model for how Australia has deployed forces—pretty much since the Second World War. Now, when we think about the Second World War, it is good to think back to how we’ve engaged in the neighbourhood before, and of course the Singapore strategy jumps out as an example. In that instance there was, basically, an approach by the Australian Government that left the battle to the Brits. We didn’t try very hard. The strategy was justification for minimal expenditure. Clearly there were problems with that approach, and the strategy did not last the war. By 1941, we had deployed our own forces into the region. Indeed, the 8th Division was spread across the archipelago, with two-thirds sent to Singapore and Malaysia (or Malaya as it was then known). And then the 23rd Brigade split, with battalions sent to Kupang, Ambon and Rabaul. While the 1941–42 allied military campaigns to defend these locations were ultimately unsuccessful, the geographic choices of Kupang, Ambon and Rabaul were actually incredibly compelling because that’s where Australia was bombed from subsequently. And guess what? The geostrategic value of this region remains today. But we’ll come back to that point later.

Interestingly, when we think about the Pacific theatre of operations during the Second World War, Australians tend to focus on the Kokoda campaign in Papua New Guinea. And to a certain extent, this is General MacArthur’s fault. Because he and Admiral Nimitz didn’t get along, they divided the Pacific between them, with MacArthur taking responsibility for the Southwest Pacific Area and Nimitz getting the rest. There was therefore a line of operational responsibility drawn basically through the Solomon Islands—and Guadalcanal (where Honiara and Henderson Field are located) was on the Nimitz side of the line. This delineation saw the US Army fight largely alongside Australian troops in Papua New Guinea and has elevated the Kokoda campaign in the Australian national psyche. What many fail to appreciate, however, is that Guadalcanal was the main effort of the Pacific campaign for very compelling reasons. Why, you ask? Because from there, you could cut off the sea lines of communication between Australia and North America. The same situation exists today. And guess who’s currently taking a lot of interest in Solomon Islands?

Now, my late great friend and colleague Allan Gyngell talked in his book Fear of Abandonment about how Australia has been afraid of being abandoned firstly by Britain after the failed Singapore strategy, and later by the US. This anxiety has shaped how Australia acts in the world. And after the Second World War, unlike after the First World War, Australia actually deployed elements of the three services (what we now know as the ADF) to Japan. These forces were there to operate alongside US occupation forces, to help ensure Australia’s interests were represented in the post-war peace arrangements. Those early years laid the foundation for what would follow. This included Indonesian independence and the birth of the People’s Republic of China. These were extraordinary events that transformed Australia’s outlook on its geography. These developments were followed shortly thereafter by the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950. We tend to forget that in January 1950, Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State, went to the National Press Club in Washington DC and declared that US interests extended to the border of Japan—in other words, not to Taiwan or Korea. Five months later, Kim Jong-un’s grandpa, Kim Il-sung, invaded the south, taking Acheson’s statement as the green light to invade. Weakness invites adventurism. Our involvement in Korea facilitated the signing of the ANZUS Treaty in September 1951.

Reflecting our concern about the Domino Theory, in 1954 Australia joined the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO), which was established in an effort to prevent the proliferation of communism in the region. While Australia hoped SEATO would be a little bit like NATO, of course it is not, largely because most of the members are extraterritorial powers, not local ones. Also a party to the SEATO agreement is Pakistan, which back then included Bangladesh, or what was then East Pakistan. And we were obviously concerned about communism. Notably, Indonesia stayed out of it. Just as is the case today, Indonesia preferred to see itself as non-aligned.

The 1960s was a period which tested Australia’s capacity to influence events within our region, particularly over the government of Sukarno in Indonesia, without the support of our US ally. During the Konfrontasi between Indonesia and Malaysia from 1963 to 1966, Australia didn’t actually do very much other than conduct exercises. Indeed, this period represented a significant formative moment for Australia as it realised the precarious nature of its security relationship with the US at that time. That’s because the US wasn’t interested in challenging Indonesia by participating in the conflict. Evidently Australia’s alliance ties through ANZUS and SEATO were not sufficiently compelling in Washington to sway US policy closer to Australian foreign policy preferences. So the Konfrontasi was a contributing factor to Australia going to Vietnam, to elicit further support for Australia, with the deployment of a brigade-sized 1st Australian Task Force as well as naval and air power capabilities. But, of course, there were limits to the influence Australia was able to exert, and this is an issue that I cover in my book about ASIO, The Protest Years. Specifically, I explore the fact that limitations exist to Australian political goodwill towards the use of force if the purpose is not clearly articulated and justified to the Australian people. The lessons from the Vietnam War still resonate today in the need to engage the Australian population about regional issues and regional security concerns. Government needs to keep the Australian people involved and brought along.

Following the Vietnam War, we had the so-called ‘Defence of Australia’ era. Paul Dibb is regarded as the architect of this policy. In it, he proposed investment in bare bases, in Northern Command, in the Army presence in the north, and in the Regional Force Surveillance Units. While the policy—and Dibb himself—has understandable detractors, the Defence of Australia construct justified keeping a three-brigade Regular Army. So I think it’s worth bearing that in mind. Pre-1960, in the 1950s, we had a one-brigade Regular Army only.

The Defence of Australia policy was, however, squarely challenged in 1987. When Fijian Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka overthrew Prime Minister Timoci Bavadra on the morning of 14 May, Prime Minister Bob Hawke called in defence minister Kim Beazley and the acting foreign minister, Gareth Evans. He said, ‘We’ve got to help Timoci Bavadra’ and then the Chief of the Defence Force, General Peter Gration, came in and said, ‘Uh, with what?’ At the time, providing such support was a ridiculous proposition. Australia was clearly unable to help the Fijian Prime Minister—we could barely launch a non-combatant evacuation operation. This event jolted the Defence of Australia oriented ADF, yet it had little enduring impact on national strategic priorities.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the Australian Government began to see its military personnel as ‘ambassador, soldier, teacher, peacekeeper’. A series of non-regional operations conducted by the ADF had the effect of revalidating the Army ethos post-Vietnam in a way that was very slightly touchy-feely, and certainly not too challenging. Notably, these were ‘operations of choice’ conducted far away, by and large. These missions were followed by some operations of less choice closer to home, in Bougainville, in Papua New Guinea, in Irian Jaya—and then again in PNG with the tsunami in 1998, which saw the ADF prepare for a natural disaster, not knowing that the crisis in East Timor would subsequently happen. Not only did the ADF’s disaster relief response help bolster regional security; it also honed the force. Working alongside partner nations, it was crucial preparation for what would follow.

The tipping point for the post-Cold War reinvigoration of the ADF was the crisis in East Timor in 1999. My friend and colleague Professor Craig Stockings has written recently about the East Timor crisis in his new book Born of Fire and Ash. While many Australians may reflect with pride on the ADF intervention, the Australian military deployment was actually the result of what Hugh White calls a strategic blunder. ‘Why a strategic blunder?’, you may ask. The reason is that Australia was never supposed to get so offside with Indonesia. The whole idea was to try to invite some kind of autonomy accord. But of course, President Habibie in Indonesia took John Howard’s letter suggesting a path to autonomy the wrong way. The military intervention also tested our alliance with the US. Why? Well, we now know that when, worried about the lack of US engagement in support of Australia over the emerging crisis, Admiral Chris Barrie, the Chief of the Defence Force, got on the phone to the Commander of Pacific Command, Admiral Dennis C Blair, to that point the US hadn’t been interested in helping us. Why? Because they were busy in Kosovo. In their view, East Timor was in Australia’s backyard, and therefore it was a problem for us to deal with. While the rationale made sense, the optics in Australia around our enduring alliance with the US were such that Prime Minister John Howard considered it critical that the US did something to help. In support of Australia, Admiral Blair got on a plane, went to Auckland where the APEC meeting was being held, and convinced US President Bill Clinton to offer some important diplomatic, financial, communications and logistics support to enable it all to happen. This critical assistance from the US is something that Australia is arguably quite proud of. Yet the US received little credit, and it probably should have.

In parallel to the ADF’s operational involvement in the region, it is also worth flagging the enduring nature of Australia’s Defence Cooperation Program (DCP). This arrangement, which offers individual and unit training exercises and educational exchanges with the armed forces of Australia’s neighbours and partner nations, was 60 years old in 2023. The DCP involves countries across South-East Asia, the South-West Pacific, South Asia and the Middle East. It is a multimillion-dollar program and generates a really interesting collaborative space for military-to-military engagement (Figure 2). As a former Defence attaché, I was actively involved in the DCP and consider it to be a fantastic program.

Figure 2. Brigadier Nerolie McDonald as Defence Attaché in Vietnam (Source: Defence image gallery).

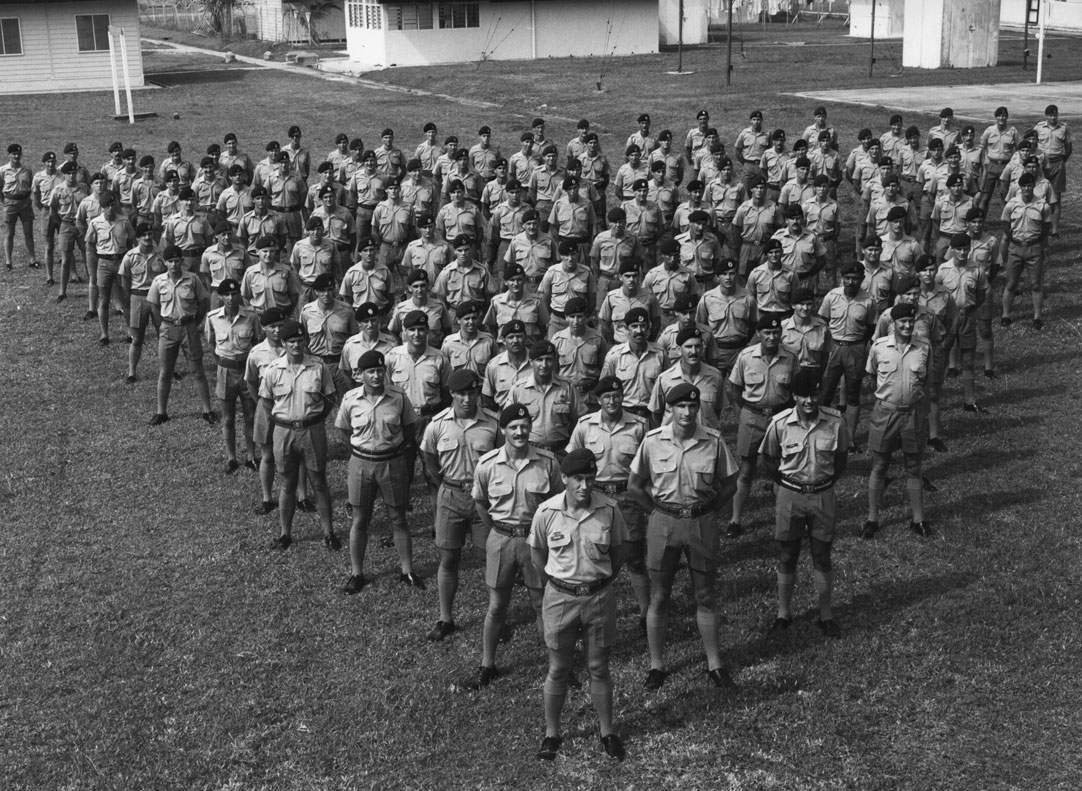

There is also the Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA) between Singapore, the UK, Malaysia, Australia and New Zealand. Established in 1971, its original purpose was to keep the UK engaged within the region after they withdrew from ‘east of Suez’, keeping Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and New Zealand engaged in mainland South-East Asia. The organisation is now 52 years old and we don’t talk much about it anymore. But this apparently anachronistic entity keeps working and all of the five countries still get enormous benefit out of it. The Integrated Area Defence System that operates within the FPDA construct has been providing a platform for defensive exercises and activities between the participating nations for years. There’s also Rifle Company Butterworth, which involves a company of Australian soldiers on three-month rotations for exercises and training in the training areas of Malaysia and Singapore (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CDF General Angus Campbell (second row) as a lieutenant during his tour with Rifle Company Butterworth (Source: reproduced courtesy of Brad Shaw).

As Australia’s sense of urgency around regional engagement has continued to grow, particularly since our East Timor intervention, the introduction into service in 2015 of the first Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD), HMAS Adelaide, is a game changer for Australia in the Pacific. In contrast to Australia’s experience in responding to the crises in Fiji in the 1980s and again in the early 2000s, the LHD now offers a much more versatile and substantial platform for the government to use in response. It is just extraordinary how LHDs have contributed to our ability to reach out and engage constructively. A leading example is Defence’s annual Exercise Indo-Pacific Endeavour, which has run since 2017 and enables constructive and tangible engagement with counterpart defence forces in the neighbourhood. The ADF can now do awesome things with Fiji, Tonga and others in the neighbourhood that were previously beyond our capacity. For example, LHDs have played a pivotal role in Australia’s delivery of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief within our region. While LHDs would undoubtedly be vulnerable in open conflict, they nevertheless play a key role in Australia’s preventative diplomacy strategy because they contribute to security, stability and deterrence in ‘phase zero’, as they call it. And it’s these operations short of war that we need to worry about, particularly in a strategic environment characterised by great power competition.

When we think about the Foreign Policy White Paper of 2017, we see that deterrence on our own was recognised as being problematic. So engagement with all and sundry constitutes Australia’s ‘foreign policy Plan B’. Today that engagement occurs across ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), the Pacific Islands Forum, the Indian Ocean Rim Association, the FPDA, and now the Quad and AUKUS as well. On the security side, we’re also seeing NATO engagement in the neighbourhood. With respect to economics, Australia is entering free-trade agreements with everybody who’ll sign one with us.

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review delivers a strategy for national security that flips Dibbs’s Defence of Australia model on its head. Today we no longer seek defence from the region, but defence ‘in’ and ‘with’ the region. This means that regional engagement is no longer just a ‘nice to have’. It is actually critically important to our security and theirs. So Indonesia and Papua New Guinea are now more important to us than arguably they’ve been for generations. And the same goes for Solomon Islands as well, despite the fact that Australia retains a geostrategic blind spot towards this part of the world because we weren’t part of Nimitz’s command in 1942. When we think about the possible requirement to cooperate through the archipelago, however, its strategic significance remains. Specifically, the key advantage of fairly short-range aircraft such as the F-35 is lost unless you can lily-pad through the archipelago in somewhere like Ambon, Kupang and Balikpapan. We know about these places from the events of the Second World War, and while Indonesia has changed politically in the intervening years, the geography hasn’t. So it is critical that Australia can collaborate by accessing and operating in the archipelago alongside the TNI (the Indonesian armed forces) and the Papua New Guinea Defence Force.

The implications for the land force are not insignificant. If Australia needs to lily-pad F-35s through the region, it needs an airfield which, I would contend, has to be secure out to about 120 mm mortar range. The task force area to secure such a strategic asset would amount to brigade size. Which begs the question: how many brigades have we got in the regular force? How many of them are ready? Not too many—right? So, if that’s what we require, we need to work with the Navy, and probably some commercial roll-on, roll-off vessels, to get there before the stoush—to have a phase-zero effect, to shape the environment. But, of course, achieving this depends on Indonesian consent and welcome. And what are we doing about making ourselves the best friends of Indonesia? Well, how many of us speak Bahasa? Not too many. By contrast, if I was in the UK asking if you spoke French, and you didn’t put your hand up, you’d be embarrassed. What’s going on? How have we let this happen?

If we reframe the international security environment in terms of unrestricted competition, guess what it looks like: the real world today. That’s where we are. We’re in unrestricted competition. It doesn’t look quite like war. And that’s because we’ve been looking at it the wrong way. We’ve conceptualised this unrestricted competition as conflict, as a chess game, where you remove players from the field and you win by capturing the king. By contrast, our strategic competitors are playing Go, where you add pieces to the board and you don’t destroy, you don’t remove; you flip your adversary. You win them over. And we’re getting outplayed. In parallel, we are facing challenges in great power competition; looming environmental catastrophes; and a spectrum of governance challenges, including people smuggling, drug smuggling, the breakdown of law and order, and terrorism. These threats are all accelerated by the fourth industrial revolution. We are dealing not just with a two-dimensional problem, and not just with war and peace, but with unrestricted competition. It’s occurring in the sea, air, land, space and cyber. It’s also happening in the human space.

So we’re talking hardware, software and—guess what—the wetware: the 15 centimetres between your ears. So now we’re looking around the region and we’re doing a lot of things with Singapore and with Thailand. We already know the enduring value of engagement with these regional partners. For example, I have a bit of a soft spot for Thailand as I’m a graduate of the Thai Army Staff College, and the King of Thailand, Nay Luang, was 10 years ahead of me at Duntroon (Figure 4). Australia has invested considerably in the relationship with Thailand, and it has invested in us. When we were in the 1999 crisis with Indonesia, we needed an ASEAN partner. We reached out to Singapore and Malaysia first, but they were a bit nervous because, understandably, Indonesia was not happy about what was going on. And then the Vice Chief of the Defence Force, Air Vice Marshal Doug Riding, went to Thailand and the Thais volunteered to assist. Indeed, they were the first Southeast Asian volunteers to help us, by providing a joint task force of 1,000 people, and the deputy force commander, General Songkitti Jaggabatara. It was really critical.

Figure 4. The Crown Prince of Thailand, Vajiralongkorn Mahidol at RMC Duntroon in 1972 (Source: National Archives of Australia 33319078).

The lesson from this experience is that we should not take regional relationships for granted. This includes our second-tier relationships. While there is not time to expand on this point, it’s important to note that we have extraordinary and mutually beneficial relations with, for example, the Philippines. And we are building stronger ties with Laos, Cambodia and Brunei as well. In Indonesia, of course, we’ve been playing a game of snakes and ladders. And we’ve got to stop doing this, be it over beef, boats, spies, clemency, Timor, Papua or Jerusalem. We keep poking Indonesia in the eye and we wonder why they get upset with us. It’s really not good enough.

Turning to the Pacific, we are engaged in a serious game of competition. This is an incredibly geostrategic region. While the land mass of the territories may be relatively small, when you add the exclusive economic zones the region is incredibly consequential economically. It is incredibly consequential for the environment, and it is incredibly consequential geostrategically for the future of Australia and the neighbourhood. And yet what do we know about the neighbourhood? Not enough. Thankfully, in 2022 US President Joe Biden introduced the Pacific Partnership Strategy. Very cleverly, he invited all of those countries that the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, had sought to engage with in the Pacific. They all came—even the Solomon Islands Prime Minister, Manasseh Sogavare (Figure 5).

Figure 5. U.S. President Biden with Prime Minister Sogavare and other leaders from the U.S. – Pacific island Country Summit in Washington DC on 29 Sep 2022 (Source: Reuters Pictures RC2BRW9YLZ99).

Regional engagement has got to be done. Today our national security challenges are exacerbated by a range of trends including floods, fires, pandemics, cyber and terrorism. They are all overlapping, leaving Australia with a conundrum the likes of which we have not faced in generations. And while I like to think I am a glass-half-full kind of guy, we have to brace ourselves for impact, ladies and gentlemen, because—to this point—these things have been happening one at a time. If they start happening concurrently, we are in a deep hole. We need to wake up as a nation to the spectrum and the scale of the challenges: looming environmental catastrophe, a spectrum of governance challenges and great power competition, accelerated by the fourth industrial revolution.

Thank you very much.

About the Author

John Blaxland is Professor of International Security and Intelligence Studies at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University, where he teaches ‘Honeypots and Overcoats: Australian Intelligence in the World’. He is also Director of the ANU North America Liaison Office. A former Army officer, he has written or co-authored a range of books including Revealing Secrets: An Unofficial History of Australian Signals Intelligence and the Advent of Cyber (UNSW Press, 2023); The US-Thai Alliance and Asian International Relations (Routledge, 2021); Niche Wars: Australia in Afghanistan and Iraq 2001–2014 (ANU Press, 2020); In from the Cold: Reflections on Australia’s Korean War (ANU Press, 2020); A Geostrategic SWOT Analysis for Australia (ANU, SDSC, 2019); The Secret Cold War (Allen & Unwin, 2016); East Timor Intervention (MUP, 2015); The Protest Years (Allen & Unwin, 2015); The Australian Army from Whitlam to Howard (Cambridge, 2014): Strategic Cousins: Australian and Canadian Expeditionary Forces and the British and American Empires (MQUP, 2006); Signals: Swift and Sure (RASigs Assoc, 1998); and Organising an Army: The Australian Experience, 1957–1965 (ANU, SDSC, 1989).