Measuring Success and Failure in an ‘Adaptive’ Army

Abstract

In 2008, the Australian Army launched its Adaptive Army initiative, an ambitious program that seeks not only to pursue a systemic approach to adaptation, but also to inculcate a culture of adaptation across all levels of the Army. Much of the success of this initiative will be contingent on the Army’s ability to monitor the progress of implementation and adjust— adapt —where necessary. That process of monitoring and adjusting requires clear measures of success and failure. This article analyses those measures, examining the way in which they can be employed to assess the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative and how the aims of that initiative should be adapted in turn to suit an evolving situation.

Introduction

The Australian Army launched its groundbreaking Adaptive Army initiative in 2008. Far more than just a restructure of higher command and control arrangements, the Adaptive Army initiative pursues a systemic approach to adaptation across all levels of the Army. Under this far-reaching initiative, management of the Army workforce, materiel and knowledge will be enhanced significantly, as will the conduct of education and training across the organisation.1 This is an ambitious undertaking which aims to instil a culture of adaptation across all levels of the Army.

The central logic of the Adaptive Army initiative is simple: if land forces are to demonstrate adaptability during operations (and effectively use ‘adaptive campaigning’), that culture of adaptation must be inculcated prior to the conduct of operations. This culture of adaptation must pervade the organisation so as to underpin the generation and preparation of land forces and provide a foundation for ‘adaptive campaigning’.

Monitoring the process of implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative and adjusting that process where necessary is also crucial, and requires clear measures of success and failure. This article seeks to examine why measures of success and failure are such an important driver in the success of the Adaptive Army initiative. Applying the culture of adaptation to these measures of success and failure in turn is also of primary concern and will be addressed in the latter stages of this discussion.

'Complex Adaptive Systems' And Adaptation

Fully exploiting the ability to adapt is necessarily based on a clear understanding of its essential elements, what drives its success or failure, its design parameters and its framework of measures.2 The Adaptive Army initiative is founded on the detailed study of adaptation and ‘complex adaptive systems’ by Defence (particularly DSTO and Army) over the past five years. Adaptation is a potent ability that is evident in many diverse biological systems. Darwin’s work on evolution featured some of the earliest research into the science of adaptation and, for many years, the study of adaptation remained primarily restricted to the field of biology.

In recent decades, however, research into adaptation has moved beyond the natural sciences and is now applied to a broad range of societal endeavours. In particular, the study of adaptation has been influential in the examination of the optimum organisation of societies, businesses and other collectives to enhance their chances of success in dynamic environments. Such research has demonstrated that the process of adaptation underpins human learning, the development of societies, organisations and cultures, and complex problem-solving. The burgeoning interest in adaptation in recent years runs parallel to developments in the scientific field of complexity.

The science of complexity has become firmly established as an important field of study over the last decade. There are two key reasons for this. First, it offers a framework for examining complex issues that provides richer insights than traditional reductionist approaches. While the reductionist approach has enormous application in complicated mechanical systems where linkages can be clearly observed, it is less useful in the study of complex human or biological systems because of their inherently complex nature. Second, the study of complexity has very broad application. It has been used in fields as diverse as climate change, education, economics, air traffic control and biology.

As the examination of adaptation has broadened and the understanding of complexity has deepened, what has become apparent is that these two fields are inextricably linked.3 This is clearly demonstrated in the burgeoning study of complex adaptive systems and their implications. A defining characteristic of all complex adaptive systems is their capacity to change composition and/or behaviour to improve their fitness for the environment they occupy.

The study of complex adaptive systems is also remarkably relevant to military organisations. Indeed, land combat, as one author noted, is a complex adaptive system. Combat is essentially ‘a nonlinear dynamical system composed of many interacting semi-autonomous and hierarchically organized agents continuously adapting to a changing environment’.4 This continuous adaptation is particularly apparent in any study of the full spectrum of military endeavour and the way in which military organisations must constantly adapt to remain successful in an environment that changes continuously.

Military organisations are complex systems that possess a range of human and technological potential for action. They must operate in multifaceted environments that contain many other complex systems—including the government that funds and directs their activities and the adversaries that seek to deny their goals. To retain their capacity for success in such an environment, military organisations have constantly fought to be innovative. It is only recently, however, that a detailed examination of the application of adaptation to military organisations and their operations has been undertaken.

Within the broad range of literature related to complex adaptive systems and adaptation, the key elements of adaptation are defined as:

- the capacity to gain and sustain environmental awareness of the system (agents, populations and relationships) in which one exists and seeks to be successful

- a notion of fitness for that environment

- the capacity to make changes (at different time scales and organisational levels) based on environmental understanding and notions of fitness

- the capacity to retain and encode useful information that improves success (corporate knowledge)

- the ability to measure the success and failure of actions in moving towards this definition of fitness which leads to further change in actions, objectives and notions of suitability.

Defining the key elements of adaptation is critical to any understanding of precisely what adaptation is. These elements are also useful in framing what measures of success and failure may be required and the level of detail necessary. Adaptation is a surprisingly conservative process. It is as much about what to retain (those elements that are successful) as it is about what needs to change. The study of adaptation and complex systems was applied throughout the development of the Adaptive Army initiative for a number of highly pertinent reasons.

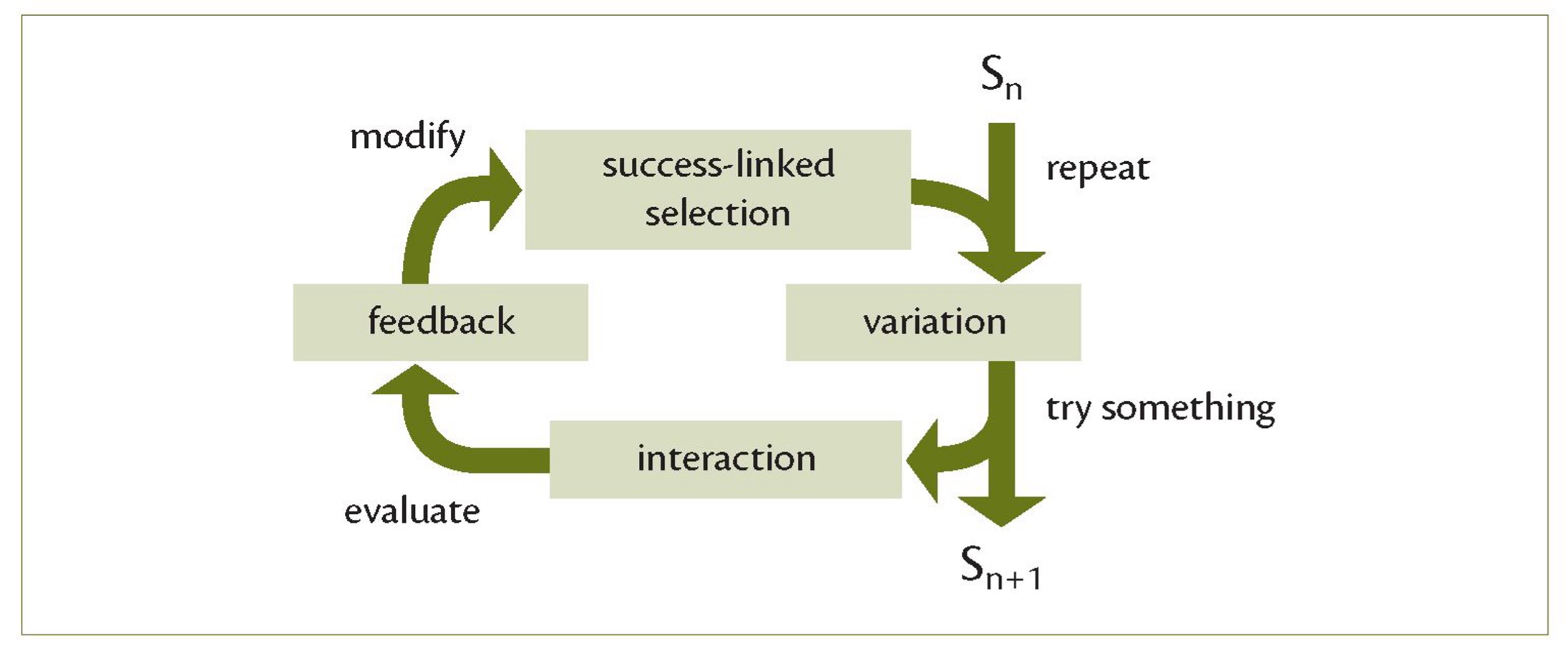

First, exploiting adaptation is the most effective way to address the challenges of complexity. The environment in which contemporary operations are conducted— and thus for which forces are prepared—is constantly changing, and the different inter-actions at different levels that characterise this change are too many and varied to accurately monitor. Second, using an approach geared to adaptation allows the Army to manage these complexities better, because adaptation does not rely on perfect situational awareness. Because of the iterative nature of adaptation (illustrated in the adaptation cycle below), an approach based on constant adaptation allows the Army to test a strategy, evaluate the outcome, modify if required and then repeat the process. The development of perfect plans or solutions in advance is not required—the Army can grow its strategies and solutions in a systemic fashion to suit the changing environment.

Finally, whether adaptation becomes the Army’s watchword or not, it will certainly be exploited by others—not necessarily adversaries. Allies and partners from other government agencies (even contractors) will all be moving through their own cycles of adaptation—consciously or otherwise. The Army has no choice but to embrace adaptation—and win the adaptation battle—in order to meet the other actors in the environments it occupies on equal terms.5

Goals Of The Adaptive Army Initiative

The development of the Adaptive Army initiative spawned a number of supporting goals which were nurtured and adapted as required. These goals provided yardsticks for ongoing assessment of the extent to which the Army has achieved its aim in restructuring its functional commands.

Figure 1. The adaptation cycle6

The supporting goals also maintain understanding of, and focus on, the Army’s aspirations to guide continuing adaptation and development. The Adaptive Army initiative was launched with five objectives:

- to improve the Army’s alignment with, and capacity to influence, the ADF’s strategic and operational joint planning

- to improve force generation and preparation while balancing operational commitments and contingency planning

- to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of training within the Army through the development of the integrated Army Training Continuum

- to improve the linkage between resource inputs and collective training outputs within the Army’s force generation and preparation continuum

- to improve the quality and timeliness of information flows throughout the Army so as to enhance the Army’s adaptation mechanisms at all levels

These objectives provide a start point for measuring the effectiveness or otherwise of the Adaptive Army initiative.

Measuring Success And Failure

The ability to measure success and failure in moving towards definitions of fitness is one of the key elements of an organisation that possesses the ability to adapt. The employment of measures of effectiveness is not new—such measures are used continuously, both explicitly and implicitly, in the military, industry, academia and in other areas of society. Measures of effectiveness are most often associated with ensuring success. In the current and future military climate, however, measures of success will be required in a more dynamic environment where full situational awareness may not be possible, and goals will be constantly adapted to ensure that the organisation retains its fitness for the surrounding environment.

In a complex environment, the key definers of success will also be heavily influenced by scale and timeframes. This provides an additional complication and implies that measures of success must be designed around the different scales that are applicable (for the Army that means the different levels of command) as well as the relevant—and often varying—timeframes. So, in an approach that is characterised by adaptability, not only must success itself be measured, but those measures of success—for different scales and timeframes—must also be subject to adaptation as the surrounding environment changes.

Key considerations in establishing measures of success are likely to include:

- measuring the speed of the Army’s ability to adapt to its environment and its capacity to replace capabilities of lower or declining fitness with those that are better suited to that environment

- the inherent capacity to protect useful capabilities; that is, the ability to retain corporate knowledge that sustains or improves performance

- the ability to influence the surrounding environment (for example, Defence or government) to maintain or improve its fitness locally, or foster the emergence of habitable regions elsewhere.7

While the need to measure success may seem obvious, the importance of measuring failure is less apparent. In describing a set of strategic goals, enunciating the important mistakes that could mar the way to these goals is often a distant afterthought. In the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative, aspirations should focus not only on success; a level of preoccupation with the potentially large and (mostly) small failures within the organisation is also necessary. Any implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative must articulate failure—and measures for its detection. For this reason, it is worth exploring why measuring failure is important and the ideal means of its measurement.

Recent examination of the performance of complex systems suggests that organisations that are at increased risk of high impact failures (such as aircraft carriers, air traffic control systems and nuclear power plants) have developed methods that allow them to cope with complexity better than most other organisations. These types of organisations are known as ‘high reliability organisations’ because they can operate in highly complex environments and yet have fewer accidents than is the case across other industries. These organisations are characterised by a preoccupation with failure, and are structured so as to recognise aberration and to intercept and arrest the development of the factors that contribute to failure.8

A veritable menu of failure mechanisms for complex systems is presented in the literature that covers this topic. Cohen and Gooch, Dixon, Naveh, Hughes-Wilson, Knox and Murray, and Horne have all documented military failures and the factors behind these disasters.9 While these examinations of failure centre on military operations, other authors such as Dietrich Dörner have analysed systemic failure through a broader range of activity.10

Dörner’s examination of the dynamics of systems failures and the reasons for the failure of individuals and organisations operating within complex systems led him to identify a series of common characteristics. These characteristics—complexity, internal dynamics, in-transparency and incomplete/incorrect understanding of the situation— all have an impact on the success or failure of systems.11 While the reasons for failure within specific systems often vary, they almost always comprise a combination of the following: the inability to manage time, difficulty in evaluating exponentially developing processes, and flawed assessment of side effects and long-term repercussions.12

Cohen and Gooch have mapped significant military failures over the last century, producing failure matrices which identify the critical pathways to misfortune and disaster.13 In seeking to adopt a more systemic approach to their analysis of failure, Cohen and Gooch categorise failure as either simple failure or complex failure. A simple failure results from one error or shortcoming, while complex failure involves more than one form of error.14 On this basis, they define the three types of errors that can result in either simple or complex failure: failure to learn, failure to anticipate, and failure to adapt.15

Another to have examined failure in the context of complex adaptive systems is Dr Anne-Marie Grisogono. Grisogono explored the reasons that organisations fail despite the presence of processes that allow adaptation, commenting that ‘adaptation does not even guarantee transient success’.16 She noted three key measures of failure in the processes of adaptation—measures that are relevant at both the individual and organisational levels: loss of agility through overspecialisation or lack of diversity; loss of useful knowledge (or corporate knowledge); and acting to reduce the habitability of the environment either locally or elsewhere such as prioritising short-term gains over longer term consequences.17

There is a significant body of continuing research into failure, failure recognition and failure prevention. This research provides the Army an opportunity to exploit the extant knowledge of failure, combined with measures of success, in order to assess the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative. The strategic changes that are at the core of the initiative must be implemented with a clear view of what constitutes success and failure—as measured against the overall goals of the initiative. These measures of success and failure must be constructed for easy accessibility by a large percentage of the workforce and, significantly, the longevity of these measures also must be assured.

Principles For Building Measures Of Success And Failure

The Army’s approach to building measures of success and failure will determine whether feedback mechanisms can assess the achievement of goals in retrospect and whether future goals need to be adapted. The construction of measures of success and failure for the Adaptive Army initiative must be based on five discrete principles drawn from the Army’s knowledge of complex adaptive systems and adaptation.

Principle 1 - Linkage. The measures must be ‘linked’ First and foremost, the Adaptive Army initiative must possess clearly defined goals. Any measures of success and failure must then be linked to these goals. The study of complex adaptive systems indicates that no action occurs in total isolation; thus, clear linkages between the different goals and measures are essential. However, the linkages should also be designed to allow the adaptation of these goals as implementation progresses.

Additionally, the measures must be linked to the measures of other organisations—under the Adaptive Army initiative, measures of success and failure cannot stand alone. For them to be relevant in a complex organisation—which is linked to other services, the Australian Defence Organisation and other departments—the measures must be linked to measures of success and failure for other outputs across the Army, Defence and government.

Principle 2 - Simplicity. The need for, and use of, measures of success and failure must be widely understood within the Army. It would be a mistake to assume that every individual automatically appreciates the rationale for measuring success and failure. The Army must provide clear guidance on the rationale for the measurement of success and failure within the Adaptive Army initiative, and a simple explanation of the implementation of these measures. This explanation should employ a plain, concise lexicon and be communicated using various media such as directives and web blogs. A short, focused package that is widely distributed for this purpose may be another effective means of dissemination. These measures of success and failure should also gravitate to a wider use for a broader range of Army activities.

Principle 3 – Feasibility. The measures must be pragmatic and feasible. This is a logical consequence of Principle 2. If the measures are complicated and not clearly linked to the Adaptive Army initiative, they will be used sporadically at best. Thus these measures must be accessible to a broad swathe of the Army workforce—both uniformed and civilian. They should be described in simple, accessible language without resort to an overly academic and complicated lexicon.

A simple explanation of these measures will also ensure a broader understanding of their usage, a wider employment, and the longevity of their application. Additionally, the measures must be feasible and practical. Broad, sweeping visions will be of no material use if it is impossible to measure the effectiveness of their implementation. The measures must be set against quantifiable outcomes and should support clear assessments of whether goals have been met or whether they will be met in the future.

Principle 4 - Scalability. There must be different measures at different scales. For these measures to be widely applicable across the Army there must be different measures for the different scales (or levels of command) within the Army. Setting the correct quantity of levels, however, may involve a delicate balancing act. If measures are employed in too few levels, the quality of feedback will be poor. If measures are developed for too many levels, the process of measuring success and failure may become overly complex and tend towards over-centralisation.

As the examination of failure indicates, maintaining a narrow focus is likely to result in an inability to recognise failure in the scales that are not measured, leading to system failure. For the purposes of the Adaptive Army initiative, measures of success and failure should focus initially on three levels of command: army, command and formation.

- Army level. Measuring success and failure at the Army level involves an assessment of effectiveness at the ‘endeavour’ level. This will demand the definition of overall measures of success and failure for the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative, for the design of the right force generation and preparation processes, and their gradual refinement both as required by the developing circumstances and a growing understanding of the situation. Importantly, at this level there must be some recognition of the fact that the Army is not an ‘island’. The endeavour level’s actions will have an impact on other services and groups within Defence and, eventually, on other government departments. The endeavour level must therefore be linked to the measures of other endeavours (see Principle 1 for more on this series of linkages).

- Functional command level. The functional command level is the linkage between the strategic planning undertaken by Army Headquarters and the tactical implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative. Given the critical role that these ‘link’ headquarters play, measuring success and failure at this level will be an important part of determining the success of the entire initiative. In particular, it is at this level that patterns will first appear in the aggregation of the results of measurement at the next level down. These patterns will provide the first indications of whether goals are being (or will be) met, thus allowing decisions to be made to adapt approaches or goals at the Army level.

- Formation level (and below). This level encompasses the measurement of everyday tasks in the conduct of individual and collective training, as well as force preparation activities. A large proportion of measurement will be undertaken at this level and thus it is vital that Army personnel at formation level understand the methods and rationale of measuring success and failure. Measurement at this level will focus primarily on retrospective assessment, with the aggregation of that data at the next level up facilitating analysis to assess progress towards the achievement of goals in the future.

Principle 5 - Temporal applicability. There must be different measures for different timeframes. Alongside achieving the correct balance in scales (see Principle 4), sits a need to balance measures for different timeframes. As the examination of failure indicates, an over-focus on short-term gains often leads to systems failure. Thus the measures must balance short-term results with measurement of long-term outcomes. The consideration of timeframes will also involve the requirement to balance measurement of what has already occurred (using lagging indicators) with measurement of the trajectory towards future achievement of goals (using leading indicators).

These principles are designed to influence the development of measures of success and failure for the Adaptive Army initiative at various levels within the Army. As each level of command possesses superior awareness of its situation, that level must be responsible for the development of measures of success and failure. Once the implementation of these measures commences, every level of command must also continue to monitor its environment to ensure that the measures remain suited to the ongoing implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative. This will require the ongoing adaptation of measures of success and failure to ensure they remain appropriate to the process of institutional change within the Army. This process of measuring success and failure, and the periodic re-assessment of those measures, should be incorporated into the everyday business of formations and commands.

Wider Application

While this article has focused primarily on the application of measures of success and failure for the Adaptive Army initiative, these measures are also applicable across a range of strategic endeavours. For example, these principles could be employed in developing measures of success and failure in the implementation of the recently released Defence White Paper or within the broader government and business communities.

Additionally, these principles could be applied to the conduct of contemporary operations. This is particularly relevant as these measures are inherently humancentric—they are about measuring the success or failure of human activity. Given the character of the current wars among the people, the application of the principles contained in this article extends well beyond the boundaries of the organisation.

Conclusion

The use of measures of success and failure in the implementation of the Adaptive Army initiative will enhance the Army’s chances of achieving the stated goals of this far-reaching initiative. Since the launch of this initiative in August 2008, there have been multiple indications that it is progressing smoothly (such as the establishment of new formations and commands) despite the lack of a formal tool to assess whether these will be more effective than their predecessor organisations.

The principles described in this article offer a pragmatic and transparent means of measuring whether the Adaptive Army initiative achieves its stated goals. Additionally, the construction of measures of success and failure offers a method of demonstrating the benefits of change to the wider Army workforce while, at the same time, providing ample evidence of the enhanced effectiveness of the Army because of those changes.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Mick Ryan graduated from the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in 1989. He deployed to East Timor with the 6 RAR Battalion Group in 2000 and, in 2005, served in Baghdad as the Deputy J3 for the Multi-National Security Transition Command-Iraq. He is a Distinguished Graduate of the United States Marine Corps (USMC) Command and Staff College and is a graduate of the USMC School of Advanced Warfighting. Lieutenant Colonel Ryan commanded the 1st Combat Engineer Regiment from 2006 until December 2007, heading the 1st Reconstruction Task Force in Afghanistan from August 2006 until April 2007. He is currently Military Assistant to the Chief of Army.

Endnotes

1 The full scope of the Adaptive Army initiative is described in Adaptive Army - An Update on the Implementation of the Adaptive Army Initiative, Department of Defence, Canberra, 7 May 2009.

2 Presentation to the Chief of Army by Dr Anne-Marie Grisogono, 10 February 2009.

3 A Grisogono, ‘Success and Failure in Adaptation’, paper presented to the New England Complex Systems Institute Conference, 2006, p. 1.

4 A Ilachinski, Land Warfare and Complexity, Part II: An Assessment of the Applicability of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complex Systems Theory to the Study of Land Warfare, Center for Naval Analyses CRM 96-68, July 1996, p. 3.

5 Based on the work of Dr Anne-Marie Grisogono.

6 Grisogono presentation, 10 February 2009.

7 Ibid.

8 KE Weick and K M Sutcliffe, Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2001, p. 3.

9 E Cohen and J Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War, Vintage Books, New York, 1991; N Dixon, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, Pimlico, London, 1976; S Naveh, In Pursuit of Military Excellence: The Evolution of Operational Theory, Frank Cass, London, 1997; J Hughes-Wilson, Military Intelligence Blunders, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2000; M Knox and W Murray, The Dynamics of Military Revolution 1300-2050, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001; A Horne, To Lose a Battle: France 1940, Little Brown and Company, Boston, 1969; A Horne, The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916, unabridged edition, Penguin Books, London, 1993.

10 D Dörner, The Logic of Failure: Recognizing and Avoiding Error in Complex Situations, Perseus Books, Cambridge, 1989.

11 Ibid., p. 37.

12 Ibid., pp. 34-35.

13 Cohen and Gooch, Military Misfortunes, pp. 54-55.

14 Ibid., pp. 24-26.

15 Ibid., p. 26.

16 Grisogono, ‘Success and Failure in Adaptation’, p. 2.

17 Ibid., p. 7.