The Importance of Resources to Capability Development

The aim of this series of posts on the Land Power Forum is to pass on what I have learned about the role of Land Capability Division (LCD) over the last two years, in helping the Chief of Army (CA) to manage the capability provided by the Australian Army.

The first post introduced the series and outlined the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) fundamental inputs to capability (FIC).[1] It highlighted how the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS 24) heralded a transformational change to the ADF’s force structure in response to Australia’s deteriorating security environment. The second post discussed the 2024 Integrated Investment Plan (IIP 24), and introduced some of the key parties on the Investment Committee (IC).[2] The third post focussed on the One Defence Capability System (ODCS).[3] It explained the relevance of this new process to capability managers, including how it differs from the superseded Defence Capability Manual, and how it nests within other relevant business processes.

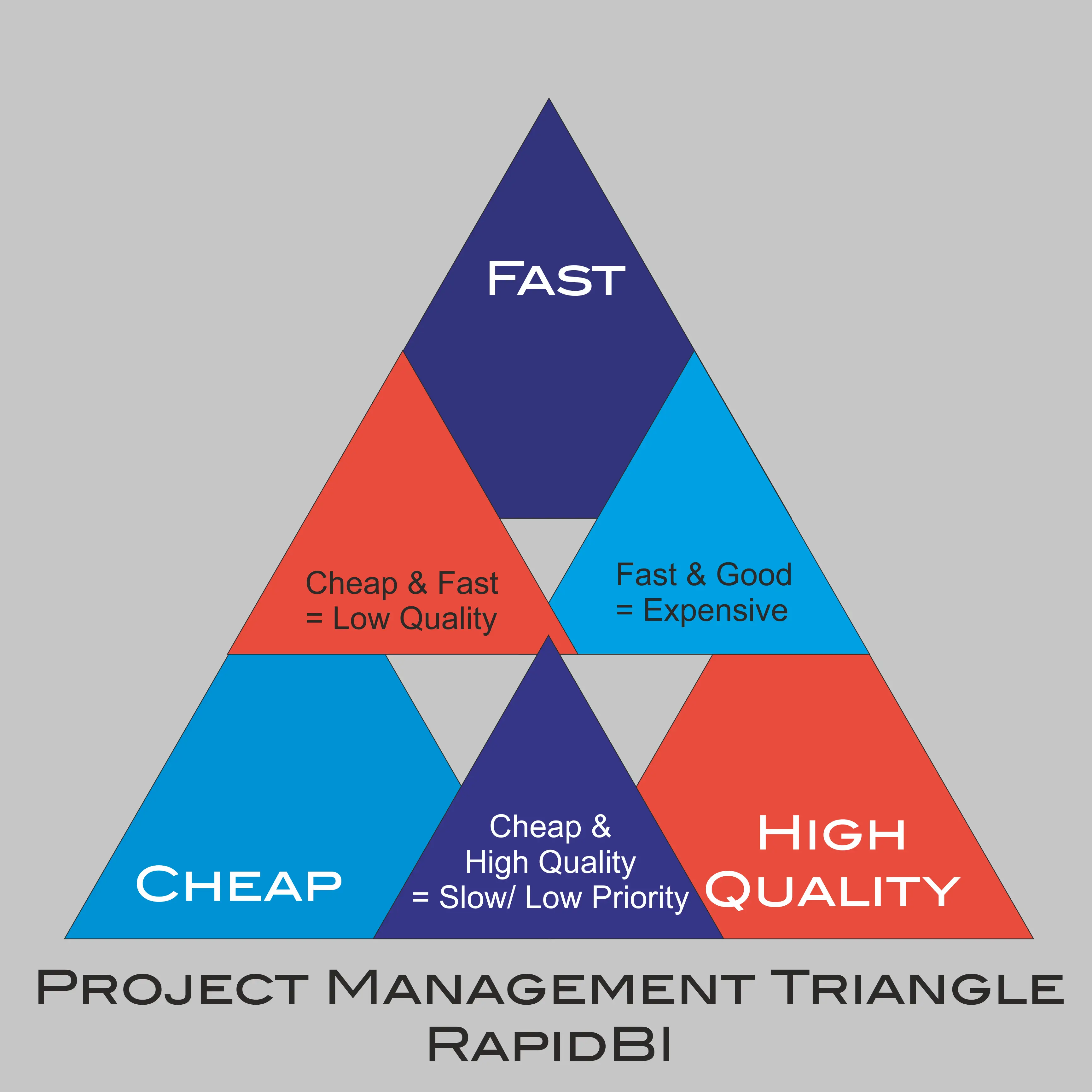

As promised in the first post, this part 4 will focus on the importance of the resources of money, people and time. These resources have an impact on the management of capability within the Australian Army. The post will also weave in the ‘iron triangle’ of project management, which is the relationship between scope, schedule and cost of a project.[4]

I picked the topic of resources based on the Chief of Army’s (CA) priorities. CA highlights that the nation we serve entrusts our Army with significant resources: people, time, machines, money and facilities. [5] In recognition of this, CA directs that we use our resources with diligence, accountability and economy. The first resource that I will discuss is money.

Money or Budgets

It seems logical to introduce the different types of money (or budgets) based on their size. The first and largest budget is the acquisition budget. It is split into ‘approved’ and ‘unapproved’ acquisition funds. Approved acquisition funds are those for which Army has received approval from Government. As an example, Project LAND 400 Phase 3 will deliver 129 new infantry fighting vehicles to Army, at a cost of $7,314 million.[6] This financial year (FY2025-26), the Capability Acquisition Program gross budget is $18,443 million. Meanwhile, Army’s acquisition budget for those projects that are in the top 30 of military equipment acquisition program approved projects is $5,267 million.[7]

Built into the system, there is an expectation that projects will not remain on schedule for a host of reasons (think of it as the capability equivalent of the fog and friction of battle). Therefore, the gross budget contains over-programming of $4,469 million. Over-programming ensures that the net acquisition budget will get spent, even if friction slows down some elements of project delivery. The net budget (the amount of money in the bank) is $13,974 million. The Defence Delivery Manager and the Capability Manager, manage this difference with their colleagues in Defence Finance Group through additional estimates in August and then budget estimates in November. If you want to learn more about this process there is a great article from The Strategist in 2013.[8]

Since the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR 23), the Department’s ability to spend its budget has improved. As the Chief of Defence Force (CDF) stated on 04 June 2025:

Defence is fully expending its budget at the moment. That’s a good thing, as we’ve uplifted our acquisition delivery, workforce is improving, our view of what we need to do around readiness. That does put pressure on a budget that we have to make choices on.[9]

This highlights another reason that the relationship between the Delivery Manager and the Capability Manager is so important. The relationship is aided by accurate shared financial data.

Next is the unapproved acquisition budget. This is the money that Government is committed to spending on a project or capability, but it has not yet approved the detailed project submission. To access this money, the Land Domain’s programs need to navigate the ODCS pathway discussed in my third Land Power Forum post. This is the budget that is outlined in the IIP 24. For example, table 5 in the IIP 24 shows the unapproved planned investments in the amphibious capable combined‑arms land system.[10]

| Capability Element |

Approved Planned Investment |

Unapproved Planned Investment |

Total Planned Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(2024-25 to 2033-34) |

(2024-25 to 2033-34) |

(2024-25 to 2033-34) |

|

| Littoral manoeuvre | |||

| Littoral manoeuvre vessels |

$35m |

$7.0bn - $10bn |

$7.0bn - $10bn |

| Combined-arms land system | |||

| Hawkei protected mobility vehicle - light |

$63m |

nil |

$63m |

| Bushmaster protected mobility vehicle - medium |

$210m |

$1.5bn - $2.0bn |

$1.7bn - $2.2bn |

| M1A2 Abrams main battle tank |

$1.5bn |

$50m -$75m |

$1.6bn |

| Redback infantry fighting vehicle |

$6.4bn |

$200m - $300m |

$6.6bn - $6.7bn |

| Boxer combat reconnaissance vehicle |

$2.3bn |

nil |

$2.3bn |

| Land mobility vehicles |

$160m |

nil |

$160m |

| Combat vehicle systems |

nil |

$100m - $150m |

$100m - $150m |

| Huntsman self-propelled howitzer |

$580m |

$15m -$20m |

$580m - $600m |

| Artillery ammunition and control |

$J4m |

$500m - $700m |

$530m - $730m |

| Combat engineering |

$130m |

$1.0bn - $1.5bn |

$1.1bn - $1.6bn |

| Uncrewed tactical systems |

$190m |

$500m - $700m |

$690m - $890m |

| Individual combat equipment |

$240m |

$2.0bn - $3.0bn |

$2.2bn - $3.2bn |

| Counter explosive hazards |

$180m |

$700m - $1.0bn |

$880m - $1.2bn |

| Reserves recapitalisation |

nil |

$200m - $300m |

$200m - $300m |

| Battlefield aviation | |||

| UH-60M Black Hawk |

$3.0bn |

$1.0bn - $1.5bn |

$4.0bn - $4.5bn |

| AH-64£ Apache |

$4.3bn |

$100m - $150m |

$4.4bn - $4.5bn |

| CH-47F Chinook |

$170m |

$400m - $500m |

$570m - $670m |

| Special operations capability |

$620m |

$1.0bn - $1.Sbn |

$1.6bn - $2.1bn |

| Total |

$20bn |

$16bn - $23bn |

$36bn - $44bn |

This unapproved planned investment equates to $5,300 million in the acquisition budget this financial year with $16-23 billion to gain approval from Government for (noting that the publication date was April 2024; LCD has been busy in the meantime). Next, I will discuss the sustainment budget.

The sustainment budget is easier to track down in the Portfolio Budget Statements 2025-26. For Army, the sustainment budget this year is $2,947.5 million (in financial year 2025-26) out of a Departmental sustainment budget of $18,758.8 million.[11] The sustainment budget is managed through a series of product lines. Army’s product with the largest budget allocation is CA Product 59 (CA59) Explosive Ordnance – Army Munitions Branch with a budget of $327 million.[12] CA59 sustains Army munitions and guided weapons. In turn, this product supports Army's explosive ordnance inventory, which consists of small arms ammunition, pyrotechnics, mortar and artillery ammunition, special purpose ammunition, demolitions stores, vehicle ammunition, direct fire and Army guided weapons. As a component of the integrated force, CA59 includes sustainment of inventory used by the Navy and Air Force where Army is the lead service. The sustainment budget also has an unapproved element associated with the unapproved acquisition budget.

Each product has a plan for the financial year. For CA59, the focus is on the improvement of the land explosive ordnance inventory, finalising (through life management plans) and transitioning new capabilities procured by major projects. For instance, ‘future artillery ammunition’ will be transitioned to ‘in-service support’. This plan also includes consideration of domestic manufacturing opportunities and in-country maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrades.

Some sustainment products can undertake acquisition-like activities. As an example, if you are replacing a broken helmet, it is highly likely that the replacement helmet is a new version with enhanced features. The use of the sustainment budget for acquisition-like activities provides the Capability Manager with a degree of flexibility on how to use the budget to support land capability. The overall management of Army’s sustainment budget is done by Director General Logistics - Army in close cooperation with the program managers and the delivery managers in Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group. The equivalent financial management activity to additional estimates is ‘fleet screens’ conducted in March and October.

The final category of money is the operating budget. The Department’s overall operating budget is $2,373 million. I have not been able to find the breakdown for the Army in the Portfolio Budget Statements 2025-26. The operating budget is the smallest budget category. Generally, for Army officers this is the only budget category we will have experienced at a unit level before coming to Army Headquarters. If your next posting is to LCD, one of your first tasks should be to understand where your projects and products are in relation to their spending plan across all three budget categories. Are they behind, on or ahead of their plan or phasing? This knowledge allows you to support CA if Army needs to slow down or accelerate spending. Next, we will discuss the relevance of time.

Time or Schedule

As the first post in this series emphasised, the DSR 23 and NDS 24 have had a profound effect on capability development. In respect to the issue of time, the DSR stated:

Ending warning time has major repercussions for Australia’s management of strategic risk. It necessitates an urgent call to action, including higher levels of military preparedness and accelerated capability development [author emphasis].[13]

This emphasis on accelerated capability development was carried through to NDS 24:

The Government has agreed to reform the Budget Process Operational Rules to streamline and accelerate processes related to the management of the Defence budget and Integrated Investment Program to deliver capability faster and improve assurance and governance mechanisms [author emphasis].[14]

So, time in capability development is a resource that needs careful management. As such, this is probably a good time to introduce the ‘project management iron triangle’ to explain how time or schedule relates to budget and scope. There are many versions of this schematic online. The version chosen for this post is by RapidBI, (an organisational effectiveness consultancy), because it does a good job of describing the interdependencies and the compromises between the relevant factors.[15]

The three points of the triangle are: schedule (or time) at the top; scope (or quality) on the right-hand side; and then budget on the left-hand side. This diagram highlights the compromises that exist in efforts to balance timeliness, cost and quality. Many would argue that, in the past, the ADF aimed for fast and good. But, in reality, we tended to achieve high quality outcomes delivered slowly. This is because the ADF has tended to prioritise quality and has been prepared to accept that achieving it takes time.

In 2020, Australia’s strategic environment changed with the removal of strategic warning time. Acknowledging this change, the NDS 24 clearly stated: ‘The integrated, focused force is designed using the minimum viable capabilities required to ensure resources are maximised and military capabilities are brought into service as quickly as possible[16]. We are now in the era of focusing on budget and schedule and accepting compromise in scope or quality during capability development. In addition to this renewed emphasis on timely outcomes, on 1 December 2025, the Government announced that Defence would now centralise capability development.[17] In combination, these reforms aim to achieve better project and budget management, cost estimation and assurance outcomes right across the life of a project.[18] The reforms reinforce the importance the Government and Defence place on achieving schedule and budget.

Recent capability announcements by the Government appear to reinforce the importance of acceleration and speed to capability. For Project Land 156 Counter Small Uncrewed Systems the Government announced:

Just six months after the establishment of Project Land 156 to continuously deliver counter-drone capability for the ADF, the Australian Government has appointed Leidos Australia as the project’s Systems Integration Partner…’[19]

In relation to the general-purpose frigate, the Government stated that ‘Defence will engage closely with the down-selected shipbuilders to progress this program and ensure Australia’s first general purpose frigate is delivered this decade’[20]. These announcements emphasise that adherence to schedule is an important consideration in contemporary acquisition.

Time is not only relevant to project delivery during the period after Government has approved a project. Time is also a factor in getting the project to Government in the first instance. In terms of the Land 156 example, that project first appeared in IIP24 in May 2024. Government approved it less than eight months later. Even larger projects such as Land 8710 Phase 2 Landing Craft Heavy, the expectation is to move through the traditional first and second pass approvals in less than two years.

NDS 24 promises reform to simplify and accelerate Defence’s acquisition processes to deliver capability more quickly in partnership with industry.[21] This includes embracing greater levels of risk both within Defence and across government agencies involved in these processes. Externally, there have been welcome changes for industry. Internally, there remains the need to conduct a significant amount of work to satisfy the Department of Defence, the central agencies and ultimately the Government that a project is value for money and has considered all the FIC. Work requires people and that is the topic of the final section of this post.

People

The Government’s response to DSR 23 stated:

The Government agrees with these recommendations and recognises that people are Defence’s most important capability. The Government will invest in the growth and retention of a highly-skilled Defence workforce.[22]

The NDS 24 reinforced this statement by highlighting that ‘people are Defence’s most important asset’.[23] Roughly 60% of LCD’s workforce is Australian Army personnel, many of whom have trained in capability management, either by studying at the Australian Command and Staff College’s Capability Manager’s Course or by participating in the LCD Professional Development Program. LCD recognises that there is a skills and experience gap for some of its workforce and provides commercial courses on topics as diverse as business acumen to strategic writing (how to write a cabinet submission). LCD is ensuring that these opportunities are outlined in the arrival letter for our new members.

In addition to its military members, LCD employs many Australian public servants. In this respect, there are several job categories to which members of the Australian Public Service (APS) can be employed.[24] These categories are similar to the variety of corps and employment categories with the Australian Army (for example, accounting and finance, administration, media and communications, procurement and contracting, project and program management and research functions). Like military personnel, public servants come from many different backgrounds, from different workforces, and have various specialisations. They bring a great diversity of thought and skills, which is necessary to tackle complex capability challenges. In contrast to structured military career progression, APS personnel are recruited direct to any level. Nevertheless, public servants (like military members) are subject to annual performance appraisal. This process has implications with regard to salary progression and the potential for performance bonus. Specifically, an annual salary increase or lump-sum payment is made to APS employees who are rated as ‘fully effective’ or better.

Beyond the military and APS workforces, LCD also engages contractors. Most Army officers would not have worked with contractors before their posting to Army Headquarters. For operational reasons, numerous Defence functions can be more efficiently and effectively carried out by external service providers. This releases military personnel for frontline/warfighting roles.[25] Contracted staff work on documents (often referred to as ‘artefacts’) to prove that project submissions are ‘match fit’. Generally, contracts are short-term (12-18 months) and relate to a specific task. Contractors provide agility and a surge in labour to help accelerate projects.

There is a Government commitment to reducing the number of contractors that work within the Department. Foremost among the reasons for this is that external service providers generally cost more than military or civilian employees. The DSR 23 stated the ‘ADF and Australian Public Service (APS) workforces are understrength, while the contractor workforce has become the largest single component workforce element in Defence’.[26] A year later, NDS 24 reinforced the Government’s ongoing concern about the number of contractors stating that ‘as a priority, Defence must move away from its current dependence on external service providers for roles that should be done by ADF or APS personnel’.[27] In response, the Department has made substantial inroads towards reducing the contracted workforce. Indeed, in November 2024 it was suggested by one commentator that ‘Defence is the only department that has [achieved] outsourcing reductions in the hundreds of millions of dollars, to the tune of $308 million’.[28]

While Defence should not unduly rely on contractors, they remain a valuable source of extra capacity. As with every capability decision, value for money considerations must inform any decision to procure an external service provider.[29] In this regard, the procurement process requires that the ‘use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth.’[30] So if you can achieve value for money and also satisfy other relevant Departmental policy requirements, it may still be appropriate to engage a contractor to support the achievement of directed outcomes.

An observation is that none of the workforces are better than the other; they are just different. The sooner that a new Army member can understand and operate within LCD’s integrated workforce, the more effective a leader they will be. There are courses to teach ADF managers about APS workforce policy (and vice versa) and I would strongly encourage new LCD members to undertake them. As a relevant article in The Forge concludes, ‘knowledge is power, and developing an understanding of the ‘other’ culture will stand the individual in good stead to thrive in an integrated workplace’. [31] You also have to work hard to get the most from your diverse team. A leadership approach that may have worked as a company commander is unlikely to work with non-military personnel. More engagements and more open communication (than you would do in a homogeneous ADF workplace) helps.

Conclusion

This post has introduced the relationship between the key resources of money, time and personnel. The efficient use of resources is a CA priority. The acquisition budget is the largest source of funding and a close relationship between the Delivery Manager and the Capability Manager through shared financial data is important. The sustainment budget provides both sustainment for land capabilities as well as a source of acquisition funding (by refreshing smaller product lines). The operating budget is the smallest budget.

The project management ‘iron triangle’ illustrated why time is an important resource. DSR 23 and NDS 24 moved to the ADF from ‘gold-plated’ capability to minimum viable capability. In practice, this change has meant compromising on scope, when required, to achieve cost (budget) and schedule (time). The more personnel resources you have the quicker you can get your project ready for Government approval.

If you do not have enough ADF and APS resources you can, if policy allows, use external service providers who are engaged under contract to perform specific tasks. This integrated workforce brings a great diversity of thought and skills, which is necessary to tackle complex capability challenges.

The next post in this series will offer a ‘deep dive’ on industry as a fundamental input to capability. Industry is both a broad term and it is an enterprise that few Army personnel will have dealt with their prior to their posting to LCD.

Endnotes

[1] See Australian Army, Land Power Forum, Lessons in Managing the Australian Army’s Capability – Part One

[2] See Australian Army, Land Power Forum, Lessons in Managing the Australian Army’s Capability – Part Two

[3] See Australian Army, Land Power Forum, Lessons in Managing the Australian Army’s Capability – Part Three

[4] RapidBi, ‘The Project Management Triangle – Time, Quality, Cost – you can have any two’, accessed at: https://rapidbi.com/time-quality-cost-you-can-have-any-two/

[5] Australian Army, The Australian Army Contribution to the National Defence Strategy / 2024, accessed at: https://www.army.gov.au/our-work/strategy/australian-army-contribution-national-defence-strategy-2024

[6] Department of Defence, Redback to bring Army some bite, accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2023-07-27/redback-bring-army-some-bite#:~:text=At%20a%20cost%20of%20between,capability%20acquisitions%20in%20Army's%20history; and Department of Defence, Budget Information, accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/about/accessing-information/budgets

[7] Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2025-26, Budget Related Paper NO. 1.4A, Defence Portfolio, P18 and P125-P134.

[8] Australian Strategic Policy Institute, ‘Graph of the week: a short history of over-programming in defence acquisition’, December 2013, accessed at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/graph-of-the-week-a-short-history-of-over-programming-in-defence-acquisition/

[9] Australian Strategic Policy Institute, accessed at: ‘Chief of defence: budget under pressure, choices must be made’, accessed at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chief-of-defence-budget-under-pressure-choice-must-be-made/

[10] Department of Defence, 2024 Integrated Investment Program, P58, accessed at https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program

[11] Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2025-26, Budget Related Paper NO. 1.4A, Defence Portfolio, P19.

[12] Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2025-26, Budget Related Paper NO. 1.4A, Defence Portfolio, Appendix C Table 55, P150.

[13] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, April 2023, P25 accessed at:

[14] Australian Government, 2024 National Defence Strategy, May 2024, P72 accessed at

[15] Mike Morrison, The Project Management Triangle – Time, Quality, Cost – you can have any two, accessed at:

https://rapidbi.com/time-quality-cost-you-can-have-any-two/

[16] Australian Government, 2024 National Defence Strategy, May 2024, P37 accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program

[17] Department of Defence, ‘Reforming Defence capability development and delivery’, December 01, 2025, accessed at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-deliveryhttps://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-12-01/reforming-defence-capability-development-delivery

[18] Department of Defence, ‘Reforming Defence capability development and delivery’, December 01, 2025, accessed at: Reforming Defence capability development and delivery | Defence Ministers

[19] Australian Government, ‘Albanese Government ramps up investment in counter-drone capabilities for ADF’, August 27, 2025, accessed at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2025-08-27/albanese-government-ramps-up-investment-counter-drone-capabilities-adf

[20] Australian Government, ‘General purpose frigate milestone reached with down-selection of shipbuilders’, November, 2024, accessed at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2024-11-25/general-purpose-frigate-milestone-reached-down-selection-shipbuilders

[21] Australian Government, 2024 National Defence Strategy, May 2024, P55

[22] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, April 2023, P107

[23] Australian Government, 2024 National Defence Strategy, May 2024, P7

[24] Department of Defence, ‘Job Categories’ accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/jobs-careers/defence-aps-jobs/job-categories

[25] The Forge, ‘Working with Contractors: Culture clash or Positive Partnership?’ accessed at: https://theforge.defence.gov.au/article/working-contractors-culture-clash-or-positive-partnership

[26] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, April 2023, P20

[27] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, April 2023, P92

[28] The Mandarin, ‘Defence the biggest loser in APS contractor mass cull’, accessed at: https://www.themandarin.com.au/280255-defence-the-biggest-loser-in-aps-contractor-mass-cull/

[29] Australian Government, ‘Value for Money’ accessed at: https://www.finance.gov.au/government/procurement/commonwealth-procurement-rules/value-money

[30] See sections 15 and 21 of the PGPA Act accessed at: https://www.finance.gov.au/government/managing-commonwealth-resources/pgpa-legislation-associated-instruments-and-policies

[31] The Forge, ‘Working With Civvies – the Integrated Workplace’, accessed at https://theforge.defence.gov.au/article/working-civvies-integrated-workplace