An introduction to the One Defence Capability System

The aim of this series of posts on the Land Power Forum is to pass on what I have learned about the role of Land Capability Division (LCD) over the last 20 months, in helping the Chief of Army (CA) to manage the capability provided by the Australian Army.

The first post introduced the series and outlined the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) fundamental inputs to capability (FIC).[i] It highlighted how the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS 24) heralded a fundamental change to the ADF’s strategic settings in response to Australia’s deteriorating security environment. The second post discussed the importance of committees, outlined the 2024 Integrated Investment Plan (IIP 24), and introduced some of the key parties on the Investment Committee (IC).

This third article will expand more on the work of LCD by explaining key aspects of the One Defence Capability System (ODCS). This includes its relevance to capability managers (CM) and how the system adapted to the release of NDS 24. Many frameworks (including legislative and policy-based) comprise the ODCS. Indeed, the ODCS is a vast inter-connected system-of-systems. The ODCS Manual is 99 pages long and helps the CM achieve the acquisition, sustainment and disposal of capability. It is available online,[ii] and there is also a portal dedicated to the ODCS on the professional development website, The Forge, operated by the Australian War College.[iii] While instructive, these resources are not the sole-source of truth, nor the only documentation guiding capability practitioners. For example, the manual is subordinate to the ODCS business management system (BMS), which is the repository for detailed ODCS guidance and process maps. Unfortunately, this resource is not available outside of Defence.

Given the existence of the ODCS Manual and guidance available on The Forge, this could be a very short post: ‘here are two relevant links – read them!’ Instead, this post provides a primer on what has changed in the ODCS Manual and why. First, we will start with some of the design principles from the manual.

What is New – Design Principles

For those readers unfamiliar with the ODCS Manual, or with the Defence Capability Policy, they guide Defence decision makers in their efforts to identify, prioritise, acquire, sustain and dispose of capability while delivering on Government’s strategic intent.[iv] The ODCS is the inter-connected system of functions and processes that govern Defence capability to optimise capability outcomes within resource limitations. The Defence Capability Policy and the ODCS Manual provides the following broad principles:[v]

- Centre led. Defence and other key agencies centralise planning and engage in a dialogue with Government on strategic priorities and threats. This reinforces a top-down approach to decision making by contrast to the Service-led (CM) bottom-up approach. The Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) translates Government’s strategic priorities into a coherent force design. The test of our force design is in the force design and assurance cycle (FDAC – more on this later) against other capability opportunities to ensure the force structure addresses identified capability priorities.

- Contestability, governance and assurance. Capability proposals undergo analysis across a number of criteria to ensure the evidence supporting submissions is of high quality, comprehensive and aligned with Government direction. This process enables well-informed Defence capability investment decisions by Government.

- Directed execution. VCDF directs the Army through the (recently introduced) integrated capability directives (ICDs). The ODCS Manual highlights that the ICDs describe the threat baseline, missions and needs of the force, and ensure that the directives nest to ADF concepts and FIC.[vi] The first ICDs are due for release with the IIP 26 and they will provide CMs and delivery managers with VCDF’s direction on the required minimum viable capability, approval pathways, delivery paths and proposed sustainment channels, as well as the strategic workforce requirements.

With the design principles relating to the redesign of the ODCS in mind, the next section will introduce and expand on some of the relevant terms, including minimum viable capability.

What is New – Definitions

There are some old definitions that have carried through to the new manual, as well as some new ones described below:[vii]

- Initial Operational Capability (IOC): IOC occurs when the first subset of a capability system is ready for operational employment. As an example, this is when a troop or platoon-sized organisation, equipped with the new platform from a project, is ready to go on operations. As noted in my first post in this series, this does not occur until all the FIC is ready.

- Final Operational Capability (FOC): FOC occurs when the full set of a capability system is ready for operational employment. To build on the example above, the achievement of FOC occurs when all three platoons that form a company are ready to deploy. Both IOC and FOC were old terms that made it into the new manual.

- Minimum Viable Capability (MVC): This is a new term defined as: a capability (inclusive of FIC) that can successfully achieve the lowest acceptable level of the directed effect in the required time and be able to be acquired, introduced into service and sustained effectively. This term is similar, but is not the same definition as was used in NDS 24.[viii] The ODCS definition emphases lowest acceptable level of the directed effect, while the context of the NDS 24 definition placed greater emphasis on speed to acquisition. Government approves MVC and the capability effect is articulated in ICDs (a concept introduced in the earlier section).

- Capability Target States (CTS): CTS is the ‘point-in-time’ objectives of a capability program, generally described in terms of operational effects and given time-periods into the future. CTS existed in the previous 2022 Defence Capability Manual.[ix]

To elucidate how these terms apply in practice, it would be helpful if the manual had provided an example. In the absence of such guidance, I offer here a crude example of a project that procures a vehicle for issue to a battalion. This vehicle has a defensive system that provides an MVC on the battlefield today. Over the course of the project’s delivery phase, more vehicles are issued and, periodically, the defensive system is updated through a series of CTS. Once the project fully delivers all of the FIC, FOC is declared and the defensive system is standardised across the fleet to the latest standard. Later on, all the systems might be refreshed again to a new CTS. In my mind, MVC is the compromise between schedule (speed) and the level of capability (remember Patton’s quote: ‘A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week’).[x] Speed requires CMs to occasionally compromise on scope to achieve schedule and cost.

What Remains the Same – Stakeholders

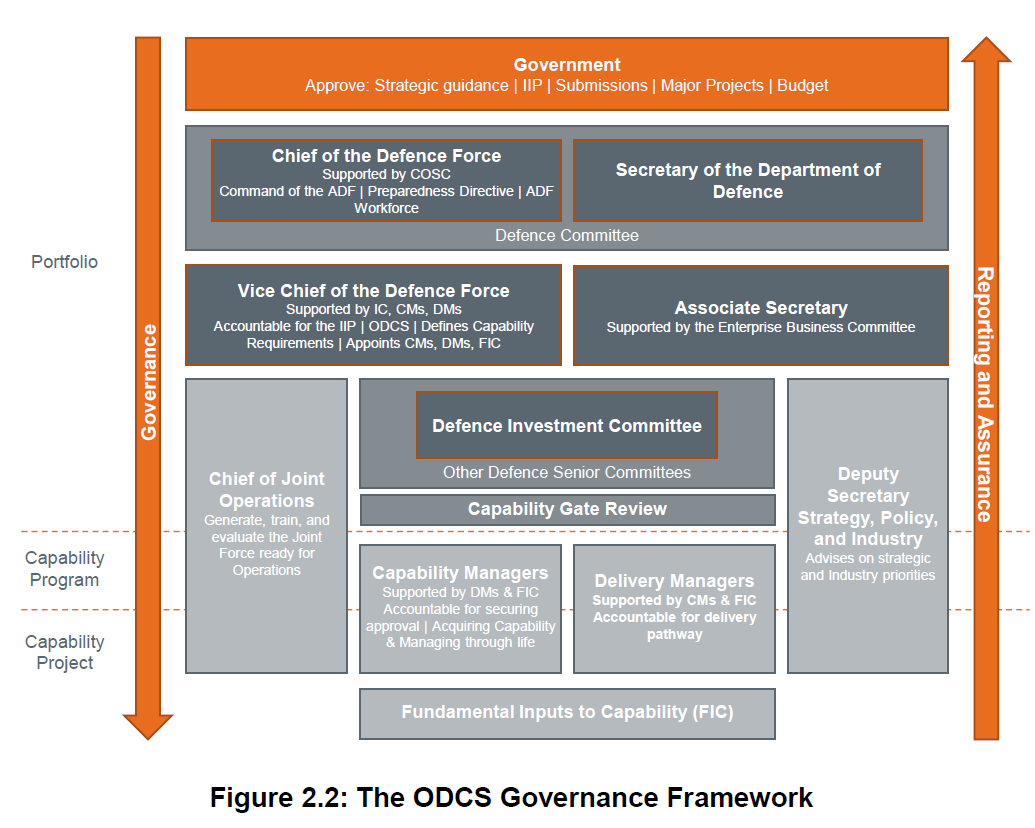

In the first section of this post, I highlighted that centralised planning is a principle of the revised ODCS Manual. There is still a role for the Chief of Army as a CM. For example, the figure below demonstrates the relationship between the CMs and delivery managers.[xi]

The CA remains accountable for the development, delivery, introduction into service, sustainment, preparedness, and disposal of capabilities, in accordance with his charter letter. As a CM, the CA is also responsible to ensure the sustainability of Army’s capabilities and to prepare them for assignment to the Chief of Joint Operations for the conduct of operations and joint exercises. Meanwhile, Head Land Capability has delegated responsibilities from the CA to oversee the work of the program, project and product sponsors, and to ensure the coordination of capability work efforts within the relevant Service or Group. Within LCD, there are branches led by brigadiers, who provide advice to the Head of Land Capability and the CA.

What is New - The Three ODCS Cycles

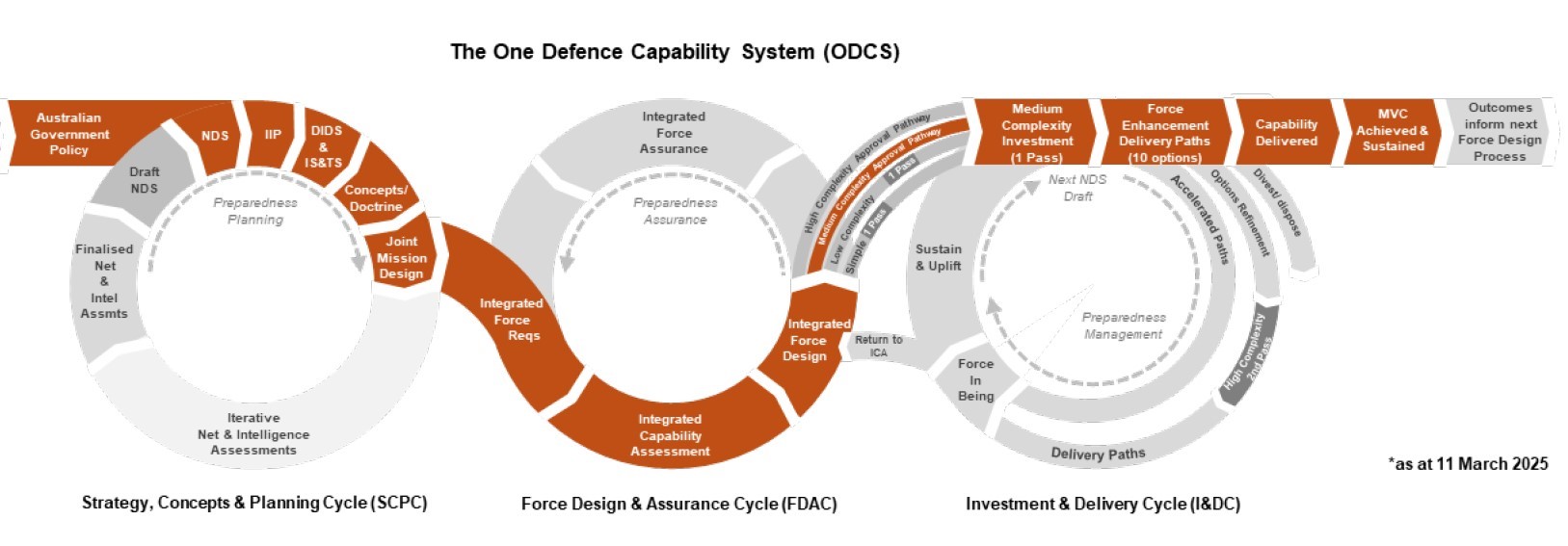

The DSR, released in 2023, recommended a biennial strategic update through a National Defence Strategy.[xii] NDS 24 is the first iteration of the strategic update with the accompanying IIP 24. The alignment of the system to Defence strategy is a continuation from the earlier manual. The change in the new manual is to align the system to the new biennial review process. Figure 1.1 illustrates the three new cycles for this process and represents a change from the four-stage linear process in the old manual.[xiii] The terms are also new. The first phase is the ‘strategy, concepts and planning cycle’, which produces the NDS and informs the development and management of capabilities within the IIP.

The second phase is the ‘force design and assurance cycle’ (FDAC). This is a centre-led review of Defence’s capabilities against Government’s strategic priorities as articulated in the NDS and balanced against the IIP. The FDAC comprises two primary activities:

- The integrated capability assessment (ICA) process assesses Defence’s capabilities, identifies gaps, as well as opportunities for innovation and/or asymmetric advantage. It also assesses capability priorities against affordability as measured by the IIP. Inputs include the integrated force design, force interoperability, and preparedness and mobilisation requirements. This process informs the development of the next iteration of the NDS, determines MVC definitions and results in the opportunity for Government to revise the IIP.

- Integrated force assurance (IFA) activities continue throughout the development and delivery of capability to ensure projects and programs are meeting Government’s strategic priorities as directed through ICDs.

The FDAC was recently the topic of the Capability Seminar 2025.[xiv] Attendance at the Capability Seminar Series is open to industry and to other government agencies. Depending on the topics under review, representantives from Defence industry and from central agencies routinely attend.

The first and second cycles operate on a two-year timeline, aligned to publication of the NDS and addressing capability priorities as defined by Government’s strategic direction. The third cycle is the ‘investment and delivery cycle’ (I&DC). CMs will progress their projects and programs through the third cycle over various timeframes, driven by factors such as life of type, and design maturity, as well as project commencement and duration. Sustainment funding is now provided on a seven-year basis.

The final section of this post will consider how CMs progress their projects and the mechanisms that the Department uses to assure the delivery of capability.

What is New – Reporting and Accountability

If we follow the ‘snake’ or pathway through the three cycles of Figure 1.1, the entry point to the I&DC occurs when Government considers a project. The National Security Investment Sub-committee (NSIS) of Government determines the approval authority and pathway for capability submissions, supported by a recommendation from IC. The pathway selection is risk-informed and depends on the project’s complexity, as shown in Table 3 from the ODCS Manual.[xv]

| Project Complexity | Standard Pathway | Accelerated Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| High Complexity | NSIS/NSC and 2 Pass | 3 MIN and 1 Pass |

| Medium Complexity | NSIS/NSC and 1 Pass | |

| Low Complexity | 2 MIN and 1 Pass | |

| Simple | 1 MIN and 1 Pass |

The more complex the project the more times (passes) the Government will want to see it. The less complex, the fewer members of the NSC will need to see it. Another innovation in the manual is to have accelerated pathways to help with the speed to capability.

Once Government approves a project, there are a number of mechanisms to manage the project’s performance. For example, there are quarterly performance reports and a ‘project of concern / interest’ list that has carried forward from the previous system. The ODCS also includes a range of additional assurance activities aimed at improving governance. One such activity is the independent assurance review, which gives decision-makers confidence that Defence is achieving approved outcomes. This review can also identify opportunities for improvement or provide early warning when programs, projects or products are at risk of moving outside set tolerances. Other processes, such as the ‘biannual health of the delivery system’ form a basis for improvements in the future and provides evidence based outcomes to influence changes to policy and processes. Beyond these examples, there are additional activities that provide a project (or program) ‘health check’ to help trouble-shoot risks or other issues. These include the integrated force assurance activities conducted in ODCS cycle 2, and the new high-level enterprise delivery assurance process that reports to the Defence Committee.

These governance processes emphasise the importance of objective data and enable oversight of capability projects by senior committees. An ANAO audit in 2019 described the processes as ‘largely effective in informing stakeholders about risks and issues in the delivery of capability to the ADF’.[xvi] Equally, the IIP biannual update to Government reviews the Department’s performance against implementation of the NDS 24. For LCD, the information for this report comes from the Defence software application CapabilityOne (C1). C1 enables effective capability management by allowing users to capture and report evidence that is relevant to the project’s intended capability effect and elements relevant to deliverables including such as scope, risk, schedule and cost. Defence leaders access C1 for high-level performance analysis of all capability domains.[xvii] CMs and delivery managers are accountable for ensuring that capability project data is up-to-date in C1.

Conclusion

This post has introduced the ODCS Manual and provided a brief description of how it differs from the earlier Defence Capability Manual in terms of design principles, new definitions, stakeholders, the cycles and the reporting mechanisms. My overall impression is that this is an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary change, which is helping the Department adopt a more ‘speed to capability’ mindset. There is also a theoretical aspect to the manual, as some of the artefacts (such as ICDs) have not yet been published. Still, Defence capability professionals should be familiar with the ODCS Manual before arriving at Russell Offices, Building 2 for their posting to LCD.

The next post will focus on the importance of resources. It will describe how money, people and time affects the management of the Australian Army’s capability.

Endnotes

[i] Mark Mankowski, ‘Lessons in Managing the Australian Army’s Capability – Part One’, Australian Army Research Centre.

[ii] Australian Government, Department of Defence, One Defence Capability System Manual, available at https://www.defence.gov.au/business-industry/industry-governance/one-defence-capability-system-manual

[iii] The Australian War College, The Forge, available at: https://theforge.defence.gov.au/jpme/technical/core-military-skills-and-joint-streams/one-defence-capability-system

[iv] DoD, One Defence Capability System, p. 7.

[v] DoD, One Defence Capability System, p. 9.

[vi] General A. Campbell, Chief of Defence Force, Building Teams Builds Power: Aspiring to a new level, Navy, Army and Air Force Newspapers, Department of Defence, Canberra, 02 February 2023, p. 2, https://www.navynewspaper.defence.gov.au/navy-news/february-2-2023/flipbook/2/ [accessed 06 June 2025], https://www.armynewspaper.defence.gov.au/army-news/february-2-2023/flipbook/2/ [accessed 06 June 2025], https://www.airforcenewspaper.defence.gov.au/airforce-news/february-2-2023/flipbook/2/ [accessed 06 June 2025].

[vii] DoD, One Defence Capability System, p. 14.

[viii] Australian Government, Department of Defence, 2024 National Defence Strategy, available at: https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program

[ix] Australian Government, Department of Defence, 2022 Defence Capability Manual.

[x] George S Patton, War as I Knew It, HarperCollins US, 1995, p. 354.

[xi] DoD, One Defence Capability System, pp. 19, 354.

[xii] Department of Defence, 2024 National Defence Strategy and 2024 Integrated Investment Program, available at: https://www.defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2024-national-defence-strategy-2024-integrated-investment-program

[xiii] Department of Defence, Defence Capability Manual, April 2022, available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/Research/Quick_Guides/2022-23/StateofAustraliasDefence

[xiv] Department of Defence, Industry training and events, available at: https://www.defence.gov.au/business-industry/training-events and https://www.defence.gov.au/business-industry/training-events/2025-defence-capability-symposium

[xv] DoD, One Defence Capability System, p. 60.

[xvi] Australian National Audit Office, Defence’s Quarterly Performance Report on Acquisition and Sustainment, 23 July 2019 available at: https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/defence-quarterly-performance-report-acquisition-and-sustainment

[xvii] DoD, One Defence Capability System, p. 78.