Embracing automation and robotics in the modern ADF

Introduction

The recent Defence Strategic Review (DSR) has brought to light significant challenges previously unnoticed by defence commentators and the broader Australian public. Two key tenets of the DSR are concerns about climate change, and the need for an asymmetric capability, which in turn pose questions about our capability to meet domestic emergencies and defence of our sovereignty.[i] The implementation of existing and emerging autonomous technologies at scale will contribute significantly towards meeting these challenges and will ensure continued preparedness in the Australian Army and the broader Australian Defence Force (ADF).

Applying such technologies presents several potent benefits to the ADF. These include the capability to handle dangerous or repetitive work, the provision of an asymmetric advantage compared to numerically superior opponents, and the capacity to enable the ADF to be at the forefront of technology. The use of these technologies by our international partners provides pertinent lessons for Australia’s future.

How Autonomous Technology can help meet our Domestic Emergency Requirements

As noted in the DSR, climate change poses additional challenges to our domestic emergency requirements with an increased prevalence of natural disasters such as floods and bushfires. Just as the Australian Army may be tasked to support national disaster relief efforts, equally it may be directed to carry out other emergency responsibilities such as searching for missing persons in remote areas.[ii] Such tasks consume considerable Defence resources with the Head of Military Strategic Commitments, Air Vice Marshal Stephen Chappell, recently observing that continued disaster relief operations ‘will place an unsustainable pressure on our ability to perform our primary role, the military defence of Australia’s national interest.’[iii] Such a use of resources is detrimental to the ADF’s aspiration to achieve accelerated preparedness.

The use of existing and emerging autonomy and robotic systems at scale by Army can both enable greater assistance of civil authorities while also reducing personnel demand. An example of this is the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by the United States National Guard to assist civilian authorities in detecting and monitoring fires.[iv] The recent adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) systems has reduced the time for a map to be produced from 6 hours to 30 minutes, thus demonstrating a synergy between robotic hardware and AI software.[v] By being able to detect and monitor fires earlier, civilian responses would become more effective thus reducing the need for prolonged disaster relief after a fire. Similar vehicles can also be used to search for missing persons. It is notable that such an approach, while effective in the United States, will need to take into Australia’s unique environment, legal constraints around UAV use, and different capabilities.

Additionally, in the aftermath of a natural disaster, emerging robots may also become capable of assisting in disaster recovery operations. Robotic dogs such as Boston Dynamic’s Spot have been deployed by overseas agencies to assist in search and rescue operations due to their dexterity.[vi] Larger robots, such as DARPA’s Legged Squad Support System (LS3), can also be used by the Australian Army to assist in domestic emergencies by carrying heavy loads such as wounded patients, debris, or supplies.[vii] By assisting in these operations, robotic technology may be able to reduce manpower demands, hence enabling enhanced readiness.

How Robotics and Automation can match our Changing Strategic Environment

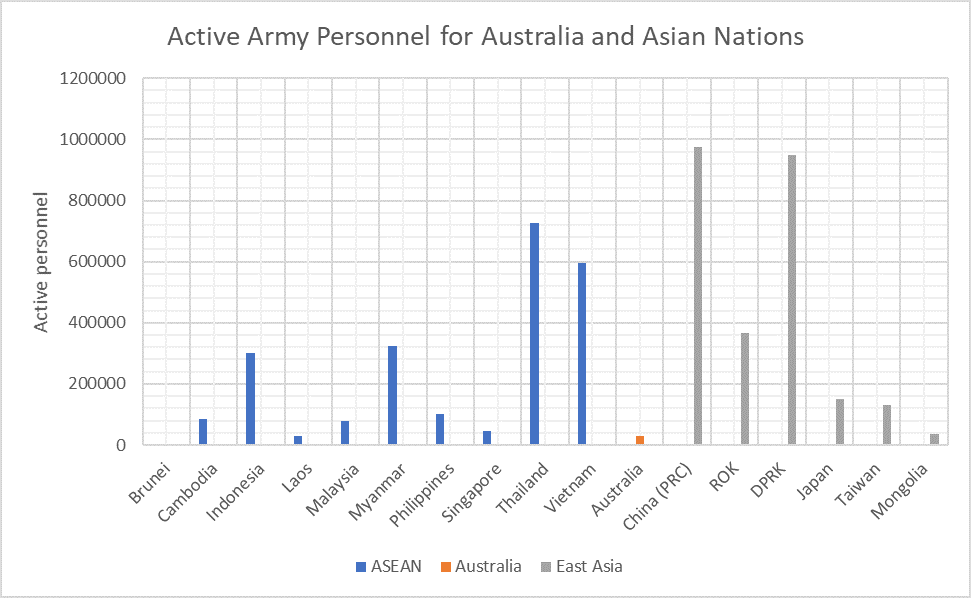

Compared to other nations in the Indo-Pacific and broader Asia-Pacific regions, the Australian Army is a relatively small fighting force. This is due to a number of factors including Australia’s relatively small population, lack of mandatory national service, and its geography. A comparison of Army forces within the region is provided in Figure 1. While in previous decades Australia’s geography shielded it from global events, such an advantage has since eroded, with the DSR noting that Australia ‘cannot rely on geography or warning time.’[viii] To effectively deter and counter considerably larger adversaries, asymmetric capabilities are required with the use of robotics and automation being an example of an emerging capability.

The use of contemporary and developing technologies in the battlefield has enabled numerically inferior forces to engage larger forces while minimising losses. Currently most fielded robots are unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), however with advances in technology, there will be increased diversity of fielded robots. Such technologies can be used to directly engage an opponent – such as a suicide drone, a quadcopter drone dropping a grenade or small bomb, or a larger drone equipped with missiles. Similarly, a reconnaissance drone can provide targeting information and intelligence for other army assets. By carrying out these roles, robotic technology can help reduce combat losses while mitigating an opponent’s numerical advantage.

How to Scale Up Capabilities in Unmanned Technologies

The Australian Army has experienced considerable capability upgrades across the years. These include the transition from Leopard to Abrams main battle tanks, increased force projection capabilities with the Navy’s fleet of Canberra Class landing helicopter docks, and the planned acquisition of rocket artillery. Robotics and autonomy is yet another of these. While welcome, these upgrades present a new set of challenges not just for the Army but also for supporting bodies such as the other uniformed services, the defence APS workforce, and industry. Meeting these challenges is a worthy aim, however, because it will support the achievement of accelerated preparedness for decades to come.

The adoption of such technologies en masse has been accomplished in Ukraine which has trained 10000 drone pilots from November 2022 to May 2023 in response to the ongoing conflict.[x] Such a time period is comparable to the duration for the Operator Unmanned Aerial Systems Course currently run by the Army[xi] but at a considerably larger scale with the entire Army possessing 1000 operators in 2019.[xii] These drones have been used effectively by the Armed Forces of Ukraine, being capable of striking both tactical and strategic Russian targets with a variety of vehicles ranging from consumer drones and custom built racing drones to military off-the shelf drones such as the Bayraktar TB2 and increasingly, sovereign developed military drones.[xiii]

From Ukraine’s experience, and considering Australia’s unique strategic circumstances, several key lessons can be gathered. The first lesson is the importance of implementing a scalable training regime, with not hundreds but thousands of personnel successfully being trained in the same period. Implementing such a program would enable increased readiness in times of crisis, and in peacetime a greater internal body of knowledge about emerging technologies.

Likewise, another pertinent learning from Ukraine’s experience is the importance of a diversity of technologies along with the importance of maintaining a level of sovereign capability. Specifically, early in the conflict, Ukraine primarily used Chinese DJI drones due to deficiencies in other consumer drones. However, imports of these drones to Ukraine were suspended due to Chinese government export controls along with China’s government maintaining neutrality in the conflict, forcing Ukraine to seek other suppliers. This situation has prompted sovereign drone development by Ukraine.[xiv] It is conceivable that Australia might face similar difficulties in attaining required technologies. For example, Australia’s direct sovereignty could be threatened by an invading power that might disrupt commercial supply routes through hostile naval action. Similarly, in the case of a broader conflict in the Indo-Pacific, allies may prioritise the capability requirements of their own forces over Australian interests.

To have a sovereign drone capability to resist these factors, substantial investment is necessary for our industrial workforce. While companies such as Boeing Defence Australia and SYPAQ are working on sovereign large and small drones respectively, the medium sized drones AAI RQ-7 Shadow used by the Australian Army are imported from the United States. To facilitate collaboration between ADF and industrial stakeholders, the Defence APS workforce would play a role in development of technologies along with oversight of work completed by industry.

Conclusion

Our changing global order demands the application of new and innovative approaches to adequately respond to the challenges expected to face Australia in the coming years. The use of automation and robotic technology, if done appropriately, will enable the Army to respond to national emergencies and defence of Australia tasks. The experiences of our allies in the United States and Ukraine can help shape our implementation of established and emerging robotic technologies, considering our different circumstances.

This article is a submission to the Spring Series 2023 Short Writing Competition, 'Army’s approach to accelerated preparedness'.

[i] Defence Australia. 2023. National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023. Review, Canberra: Defence Australia.

[ii] Triple M. 2021. Defence Force Called In To Help Find Missing Man In Central Queensland. October 29.

[iii] Shepherd, Tory. 2023. ‘Unsustainable’ for ADF to help with natural disasters and defend Australia, inquiry told. The Guardian. June 14.

[iv] McLaughlin, Elizabeth. 2018. National Guard using Reaper drone to fight wildfires. ABC News Network. August 16.

[v] Simonite, Tom. 2020. The National Guard's Fire-Mapping Drones Get an AI Upgrade. Condé Nast. September 29.

[vi] Marcius, Chelsia Rose. 2022. See 'Spot' Save: Robot Dogs Join the New York Fire Department. The New York Times. March 17.

[vii] Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency - DARPA. n.d. LS3 Pack Mule.

[viii] Defence Australia. 2023. National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023. Review, Canberra: Defence Australia.

[ix] Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 2023. Royal Brunei Land Forces, Royal Cambodian Army, Indonesian Army, Lao People's Armed Forces, Malaysian Army, Myanmar Army, Philippine Army, Singapore Army, Royal Thai Army, People's Army of Vietnam, Australian Army, People's Liberation Army Ground Force, Republic of Korea Army, Korean People's Army Ground Force, Japan Ground Self-Defense Force, Republic of China Army, Mongolian Ground Force

[x] Pannell, Ian, and Allie Weintraub. 2023. Inside Ukraine's efforts to bring an 'army of drones' to war against Russia. ABC News Network. September 15.

[xi] ADF Careers. n.d. Drone Operator.

[xii] Bardoe, Baz. 2019. Drones and Defence: The ADF and Unmanned Aerial Systems. December 7.

[xiii] Cotovio, Vasco, Tim Lister, Frederik Peitlgen, William Bonnett, and Daria Tarasova. 2023. Exclusive: Inside Ukraine's secretive drone program. Cable News Network. June 3.

[xiv] McDonald, Joe. 2023. China restricts civilian drone exports, citing Ukraine and concern about military use. The Associated Press. August 1.

The views expressed in this article and subsequent comments are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Australian Army, the Department of Defence or the Australian Government.

Using the Contribute page you can either submit an article in response to this or register/login to make comments.