Surf and Turf Operations

Cavalry’s Role in Delivering Asymmetric Effects in the Littoral Domain

‘Force intact. Still fighting. Badly need boots, quinine, money, and Tommy-gun ammunition.’

– 2nd Independent Company Transmission to Australian Northern Force Headquarters, 1942

Introduction

The 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) directs the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to optimise for littoral manoeuvre in Australia’s primary area of military interest (PAMI). This direction is made in the context of great power competition and reduced warning time.[1] The NDS prescribes the strategic antidote to this complex problem: enhanced focus and integration, and harnessing asymmetry to offset Australia’s weaknesses and promote its strengths.[2] Achieving this remit requires the ADF to think differently about its effective responses.

Given the complex interrelated drivers of regional security, the ADF faces a considerable challenge in its efforts to implement the NDS. To deliver the outcomes demanded by government, strategists, joint and domain-level force designers, operational planners, and tacticians alike will need to effectively consider the geopolitical and military landscapes that shape Australia’s unique security challenges. They will need to assess what measures may be needed to ensure the ADF can achieve the levels of innovation and adaptation required to perform across the spectrum from competition to conflict. Before identifying the specific contribution that this paper makes to assisting members of the ADF to meet this complex challenge, it is useful to briefly summarise the most relevant characteristics of Australia’s operating environment.

The Modern Characteristics of Australia’s Operating Environment

The Indo-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions comprise littoral terrain including archipelagic, riverine, high-seas, urban, mountainous, coastal, and jungle environments. The regions’ societies are characterised by diverse multiethnic groups who live in growing medium and small nation-states with disparate levels of economic prosperity.[3] Within this vast area, the policies of middle and great powers shape alliances and preferences among states, while internal social order remains shaped by factors ranging from local tribal to mass-based influences.[4] The information environment includes internet-enabled global-reach technology which allows for information to move rapidly among populations, and demands that potential security flashpoints are both identified and managed quickly.

Although the region is not in conflict, there are several characteristics of enduring great power competition that are relevant to it. First, the balance of power struggle that plays out within the PAMI indicates that the great powers recognise the value of the region to both their offensive and defensive strategies. Having said that, it is fair to say that tactical-level defensive operations have come to assume prevalence over offensive actions. This is largely because of the lethality, low cost, and range of modern anti-access area-denial (A2AD) weapons. The availability of this type of capability sees states less willing to centralise offensive and expeditionary capabilities in hard-to-defend and expensive-to-replace (both in time and in cost) capital systems like aircraft carriers, ballistic missile submarines, large transport ships, and targetable heavy transport aircraft. This reluctance is underscored by a recognition that the nature of the region’s challenging littoral terrain hinders large-scale offensive ground manoeuvre with canalising ground and sea mobility corridors, as well as complex close country.[5] Further, the prevalence within the information environment of open-source and layered classified intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) technology impedes the achievement of total surprise at the tactical level.[6]

These factors combine to raise a number of questions for strategic, operational and tactical level planners alike. These questions can be summarised as follows:

- Does the ADF possess a capability to respond to regional competition and potential future conflict that can be utilised without committing and exhausting its primary (and somewhat irreplaceable) operational or strategic assets?

- Could such a capability operate in asymmetric ways to offset Australia’s strategic vulnerabilities and promote its strengths?

- Outside the realm of strategic assets or special operations capabilities, is there a versatile capability or unit optimised for long-term shaping and decisive action below and above the threshold of war?

- Does the ADF have a functional military case study where a force deployed for a peacetime mission was retasked as a ‘trip-wire-like force’ to gain time for diplomatic negotiations against an adversary with superior mass and technological overmatch?

- What capabilities are available to respond and survive on operations, noting that the ADF might face a mass and technological undermatch with a regional opponent?

- Is there a capability that can be forward-deployed now that can be retasked in response to changes in the regional security situation without having to expose or commit operational-level lift, command, control and communication systems, or logistics capabilities?

- Could this force achieve asymmetric outcomes against a force with (likely) superior mass and technological overmatch, noting that a great power conflict would challenge the depth of Australia’s modest force-in-being?

- Is there an existing ADF unit that trains in useful security operations for peacetime operations, such as reconnaissance and surveillance partner force capacity, while also being competent in combat?

- How can the demand for ‘asymmetry’ be made meaningful to diggers with cordite, sweat and dirt on their faces when it all goes ‘non-theoretical’?

Purpose

This paper aims to assist strategists, joint and land-domain force designers, operational planners, and tacticians to grapple with the challenging issues identified above. Achieving solutions naturally requires a working interpretation of asymmetry. Accordingly, this paper begins by reviewing Rod Thornton’s examination of this concept. This is followed by a case study drawing on the World War II experience of the No. 2 Independent Company (known as 2nd Independent Company, or 2/2nd IC, and later as 2/2nd Commando Squadron). The case study is instructive as it demonstrates a situation in which Army was able to achieve relative advantage against a stronger opponent using the attributes of asymmetry, supported by a strong company ethos of initiative combined with organisational flexibility.

The paper then identifies Army’s cavalry as the ADF’s conventional force best suited to achieving the kinds of asymmetric outcomes demanded by the NDS. Using operations conducted by the 2/2nd IC in Timor during World War II as historical context, the paper demonstrates that Army’s modern cavalry has many of the characteristics that made 2/2nd IC successful. Just as 2/2nd IC did during the 1940s, the modern cavalry now bridges the gap between strategic-level special operations units and Army’s conventional brigade and divisional formations-it is more than a brigade advance guard.[7] Indeed, today’s cavalry not only performs many functions comparable with 2/2nd IC’s historical operations; it also possesses the flexibility to expand its role as the strategic and operational situation demands. This capacity for adaptation makes cavalry a versatile and asymmetric force in contemporary military operations, alleviates pressure on Australia’s special operations forces (SOF), and preserves Australia’s infantry battlegroups for decisive action.

This paper provides Army planners with an enhanced understanding of what cavalry offers Australia’s integrated force. From the analysis, strategic and operational planners should recognise that cavalry deployment-at both the operational and tactical levels-enables Australia to retain decision advantage over its opponents, to offset its weaknesses of mass, and to mitigate some of its technology deficiencies. It demonstrates why commanders and operations staff at the divisional (joint task force), brigade (joint task group), battalion (joint task unit) and tactical levels (henceforth referred to as tacticians) should seek cavalry augmentation during all competition, crisis or conflict activities. Based on the demonstrated utility of cavalry, the final part of the paper provides a basis for cavalry units to refine their tactical action list (TAL, formerly Mission Essential Task List) and to focus and hone their capability procurement focus, formally updating it to meet Australia’s evolving strategic circumstances. This change should occur as soon as possible.

Asymmetry

Rather than evaluating cavalry against a broad range of metrics, such as doctrinal principles or characteristics, this analysis focuses specifically on asymmetry. That is not to say that other measures are not useful-a traffic light evaluation of cavalry against The Australian Army Contribution to the National Defence Strategy 2024 would yield strong results. Nevertheless, this paper aims to deepen readers’ understanding of asymmetry and its strategic value, focusing on cavalry as a vector.

While the Department of Defence (Defence) publishes documents that provide an interpretation of asymmetry as it applies to military operations, US scholar Rod Thornton offers a particularly succinct definition:

At its simplest, asymmetric warfare is violent action undertaken by the have-nots, be they state or sub-state actors, seek to generate profound effects-at all levels of warfare (however defined), from the tactical to the strategic-by employing their own relative advantages to the vulnerabilities of much stronger opponents.[8]

While Thornton is a specialist in unconventional warfare within a US context, his definition has broader application because it focuses on the elements of disproportionality, relative advantage against a stronger opponent, and lack of organisational conservatism.[9] Accordingly, the definition bridges the two aspects of asymmetry addressed in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR): disproportionality and the pitting of one’s strength against another’s weakness.[10] Indeed, as will be shown in the next section, these factors proved critical in 2/2nd IC’s achievement of its asymmetric advantage in Timor during World War II.

Weak or Strong, and Why World War II?

In some respects, Australians might consider themselves part of the strategic ‘haves’ due to the country’s alignment with the dominant global rules-based order. The country’s politicians certainly held this view as Australia entered World War II as an ‘Allied power’ and similar sentiments shaped Australia’s commitments to the Middle East and Central Asia in the preceding decades – as a coalition 'have'. Despite justifiable confidence in Australia’s strategic alliances, this paper argues that it is more prudent for military planners to consider Australia as a ‘have not’ at the operational and tactical levels due to the challenges identified in the DSR and the NDS.[11] Military theorist Ivan Arreguin-Toft defines these ‘have nots’ as ‘weak actors’ compared to the relative material power of a competitor or adversary.[12] In World War II, using Arreguin-Toft’s definition, Australia was a weak strategic actor by itself, a strong strategic actor when considered as part of the combined alliance, and a weak operational actor. Tactically, Australia demonstrated both strong and weak actor traits, depending on the campaign. Ultimately, by 1942, demonstrated deficiencies in the Allies’ materiel forced not only Australia but other Allies as well to resort to asymmetric approaches to combat operations.

The security challenges posed by today’s great power competition within the Indo-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions are not dissimilar to those faced during World War II. While the bravery and tenacity of Australian troops on operations must be acknowledged, the reality remains that Australia faces several critical vulnerabilities. In determining how Australia might best respond to security challenges within our region today, study of its World War II experiences is extremely useful. During the war, Australia had to consistently balance unilateral and coalition responsibilities that competed for resources and forced hard decisions about force structure, posture and preparedness from a place of material disadvantage. It is for this reason that this paper urges modern military planners to reflect on these experiences again now-even though Australia is not at war.

The parallels between the strategic circumstances faced by 2/2nd IC in Timor during World War II resonate particularly strongly. First, 2/2nd IC operated in the same geographic area as the modern PAMI, including the prevalence both of foreign states and of Australian offshore territorial interests. Second, 2/2nd IC helped the Allies navigate the difficulties associated with the great powers maintaining interests within foreign territories (including the United States Pacific bases, the Dutch in the Netherlands East Indies, the Portuguese in their colonies, and the British-not to mention Imperial Japan, which ultimately became the Allies’ foe). This situation mirrors the context in which the ADF conducts international engagement within the region today, including its in-country programs of training and exercises as well as its involvement in the multinational forums that support the Australian government to build meaningful relationships with nations within the PAMI. Third, 2/2nd IC endured combined (Allied) strategic differences that both hampered and assisted its operational effectiveness. Today, when the ADF is involved in regional commitments, it still needs to negotiate the reality that the unilateral and combined priorities of states operating within the region will inevitably differ. Fourth, during World War II, 2/2nd IC faced an enemy with all the characteristics of a ‘stronger actor’ including greater mass, air superiority, and better logistics, firepower and ground mobility, as well as more secure basing and operational lines of supply and communication. While Australia does not have a prescribed enemy, should it enter a war among the great powers, its middle power status and modest defence industry indicate that it would inevitably concede superiority in a number of these areas.

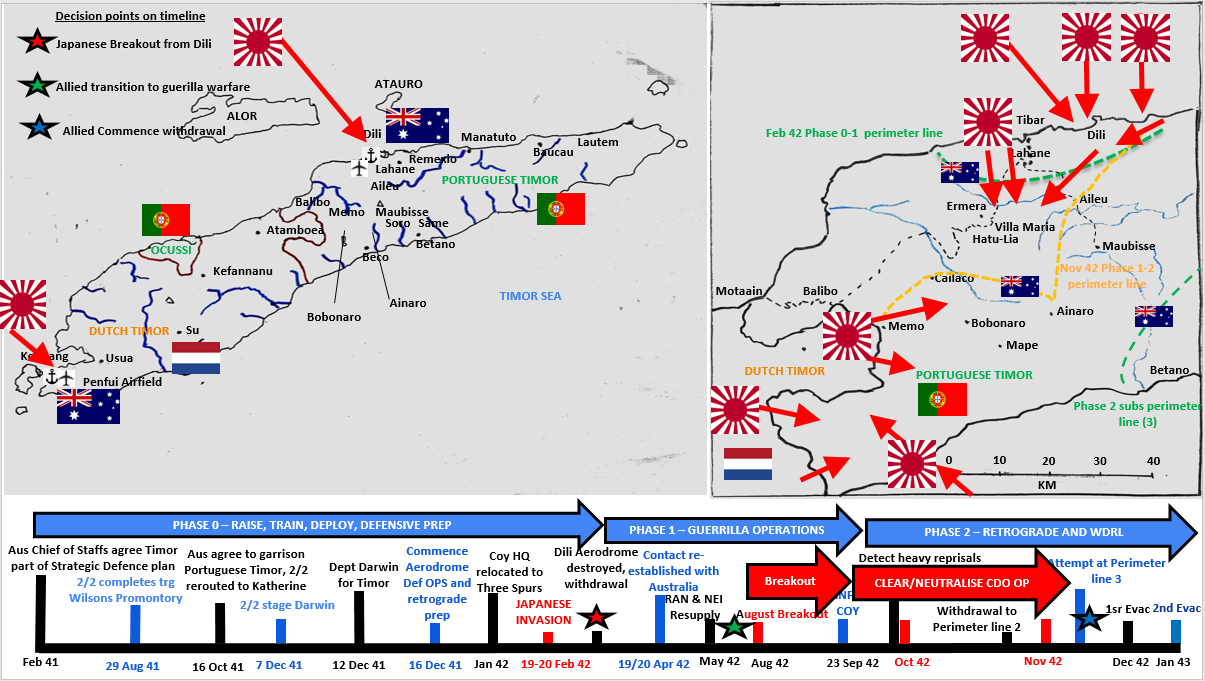

2/2nd Independent Company-Timor 1941–43

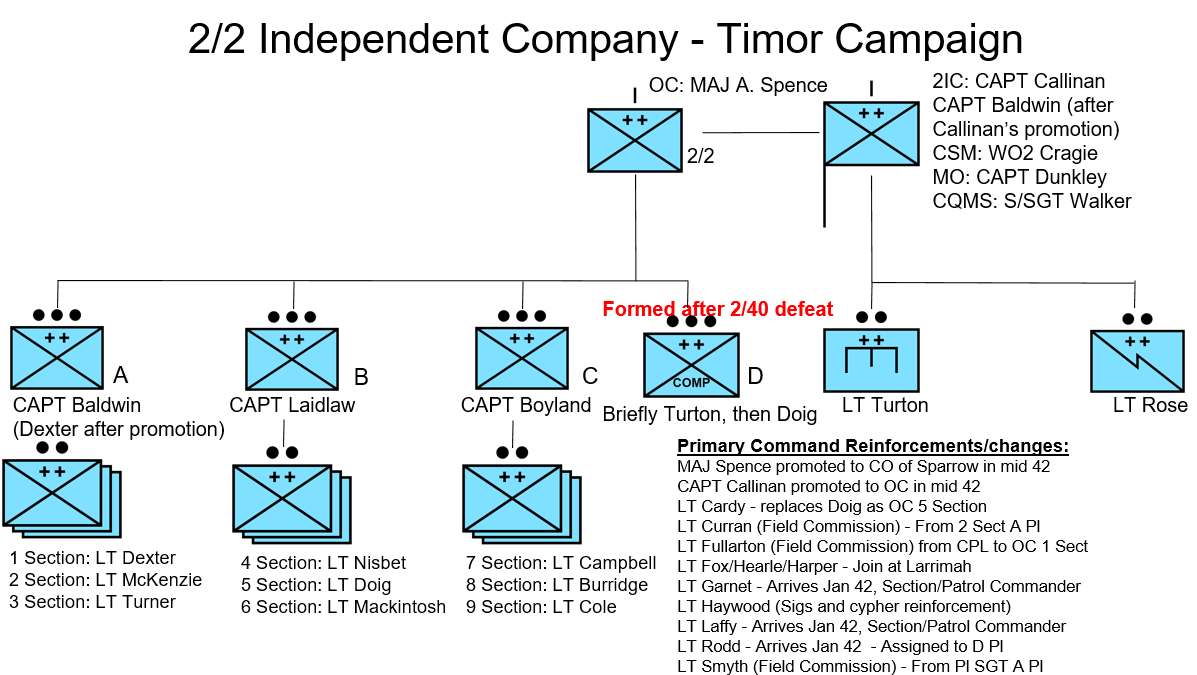

The 2/2nd IC was one of the Australian independent formations conceptualised around the British independent company (later commando) model during World War II (see Figure 1 for a depiction of the order of battle). As part of Sparrow Force (2/40th Battalion and an artillery contingent), the 2/2nd IC was deployed by the Australian government into Timor without the permission of the neutral Portuguese sovereign government and with ambiguous orders to ‘hold Timor’ as part of the northern archipelagic defensive barrier.[13] Arriving in Dili on 17 December 1941, 2/2nd IC found itself negotiating its military presence in an uncertain environment with Portuguese garrison troops and diplomats, though they did not contest the arrival of Australian troops. In parallel, the company began to occupy a mixture of high-ground observation posts and conventional defensive positions at Dili aerodrome. After the Imperial Japanese forces subsequently landed on 20 February 1942, their assaults into Timor routed the main body of Sparrow Force from Koepang (now Kupang) and forced 2/2nd IC into the mountainous terrain south of Dili.[14] For the following 12 months, 2/2nd IC as part of the Army adopted an operational defence posture, transitioning to a blend of tactics commensurate with both cavalry employment and guerilla warfare. These tactics included raids and ambushes against Imperial Japanese forces, degrading the Japanese attempts to break out from Dili. For over three of these months, Australia lost contact with 2/2nd IC, and commanders assumed the company had been destroyed.[15] Instead, 2/2nd IC was waging a defensive and retrograde operation across Timor, training indigenous security forces, conducting operational-level reconnaissance and surveillance, and engaging in limited offensive and defensive operations against the Imperial Japanese bases, outposts and patrols. Despite the immense challenges it faced, 2/2nd IC proved itself able to sustain two of the key factors that characterise asymmetric operations: disproportionality and lack of organisational conservatism. These efforts earned 2/2nd IC the moniker ‘tattered cavalry’ (not dissimilar to their compatriots in 2/6th Independent Company, who by 1943 were calling themselves ‘jungle cavalry’).[16]

Although highly self-sufficient, 2/2nd IC did not work in isolation; it augmented itself with remnants from Sparrow Force who had avoided capture and destruction, and worked with Special Operations Executive-Australia (SOE-A) personnel (albeit sporadically and without strategic or operational synchronisation). It also integrated Portuguese and Dutch colonial nationals and the Timorese indigenous populace into its ranks as combat and support forces.[17] Throughout this period, 2/2nd IC sustained itself through aerial and maritime resupply, foraging, support from the local populace, and pillaging Imperial Japanese supplies.[18] The early successes of 2/2nd IC were subsequently reinforced by the arrival of 2/4th Independent Company in Timor in September 1942. In combination, these efforts supported Allied plans to increase pressure on Imperial Japanese garrisons in Timor.[19]

Buoyed by the successes achieved in Timor, the commander of South West Pacific Area Command (SWPA), General Douglas MacArthur, briefly considered conducting a corps-level amphibious offensive operation there as part of the Allies’ campaign of sequential island hopping to gain operational dominance over Imperial Japan.[20] This planning, however, was stymied when, in August 1942, Japan commenced its offensive in Timor to destroy Australian forces on the island. As depicted in the campaign summary in Figure 2, the Japanese offensive was backed by air-to-ground reconnaissance and strike integration, motorised transport, amphibious reinforcement, and reports of increasingly brutal treatment of local nationals.

In the face of overwhelming Japanese force, 2/2nd IC was ultimately unable to generate and sustain the relative advantage it had initially enjoyed. The sheer strength of Japan’s August offensive forced 2/2nd IC into a retrograde action across the Timor highlands to the coast. The 2/2nd IC’s dwindling supplies, insecure resupply and lack of integral mobility; the existence of informants for the Japanese within the local populace; inconsistent inter-theatre and intra-theatre communications; and sickness and death characterised 2/2nd IC’s final months in country.[21] Ultimately the force withdrew from Timor in December 1942 and January 1943, before reconstituting and redeploying to New Guinea in June 1943.

Factors of Asymmetry—Lack of Organisational Conservatism

As a unit, 2/2nd IC was structurally, functionally and tactically at odds with other formations -specifically, it lacked the organisational conservatism that characterised Army more broadly. It had an unorthodox flexible organisational structure with a flat hierarchy. The relatively high numbers of officers and senior non-commissioned officers made it capable of independent and augmented operations for which other Australian conventional divisional formations were unstructured and untrained. In practice, this structure enabled 2/2nd IC to incorporate stragglers from the beleaguered 2/40th and to integrate indigenous Timorese troops within its ranks during its Timor operations.[22] The 2/2nd IC was functionally revolutionary in that it was assigned diverse tasks that included indigenous force capacity building; reconnaissance, surveillance and other security operations; limited coup de main offensive operations such as raids; support to main defensive operations; and sabotage. It was also tactically unorthodox because it quickly assimilated new technologies and tactics: training for the desert, orienting to conventional airfield defence and demolitions, and then switching to commando retrograde operations in the jungle within weeks.

The similarity between the operational approach taken by 2/2nd IC and that historically taken by cavalry was not lost on the Australian command. In mid 1943, the Australian Army formally restructured its three divisional cavalry units (armoured car and light tank based) to generate cavalry commando regiment headquarters with three subordinate squadrons each (some members of the previous cavalry formations being reassigned to the ranks of these new squadrons).[23] The Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) owes its origins to these historical antecedents, and the operations of its cavalry are still characterised by structural and functional flexibility.[24]

Cavalry’s Flexible Organisational Structure

Over the last 25 years, the Australian cavalry has conducted formed-group operational deployments to Timor-Leste, Iraq and Afghanistan. Throughout this period, it has demonstrated structural versatility at section level (paired vehicle), patrol level (three vehicle), troop and platoon levels, and squadron (company) level, and in the command of battlegroup-level operations.[25] One of the distinguishing characteristics of cavalry forces is their ability to regroup quickly and efficiently-much as the 2/2nd IC managed by raising its fourth sub-unit. This is attributable to three unique factors. First, the cavalry basic building block-the patrol-possesses command at a rank (either sergeant or lieutenant) with the commensurate knowledge, skills and attributes to understand the complexities of combined arms regrouping, to conduct and contribute to tactical and technical future planning, and to command and control subordinate section-sized combined arms forces. This is in contrast to the infantry, where the baseline building block-the section-is commanded by a corporal and thus is not optimised for command of both itself and an attached section-sized force. The infantry section’s parent organisation, the platoon (commanded by a lieutenant) is similarly less suited to being split in half, compared to a cavalry troop, noting that a platoon traditionally possesses three rifle sections.

Second, the patrol, when equipped appropriately, possesses a micro combined arms array that makes it suitable for employment and augmentation without the need for restructuring-it can move, shoot and communicate independently. Traditionally, a cavalry patrol contains a mixture of a direct-fire weapons system (such as a 25 mm chain gun and multiple machine guns capable of air and ground interdiction), a drone, and anti-armour weapons (such as a 66 mm SRAAW, 84 mm Carl Gustaf, and FGM-148 Javelin); has storage space for additional petrols, oils, and lubricants; and has the radio harness space and spare seat availability for augmented personnel. This includes but is not limited to an engineer section, joint terminal attack controller, joint fires team, or infantry section integration. This is in contrast to mounted infantry forces, where excess seats in vehicles are few, and direct-fire support weapons and signals capabilities are held at battalion level within Support Company and employed in support of the battalion commander’s priorities.

Third, the cavalry patrol’s technical expertise makes it suitable for attachment at lower levels for longer. From corporal rank, cavalry forces specialise in an employment category testing officer skill that make the small team more self-sufficient. The three specialties of communications instructor, driving and servicing instructor, and gunnery instructor mean that cavalry forces can fault find and repair issues where other forces, such as SOF or infantry, would normally require the augmentation of signals personnel, mechanics, or fitter-armourers.

Functionally, cavalry can operate as the supported or supporting force and can rapidly transition from one to the other. Cavalry is uniquely comfortable with this shift due to the dynamic nature of its missions. Cavalry is well practised in transitioning quickly from a screen into a raiding force, transitioning from a flank guard into a spoiling attack force, and transitioning from a coup de main into rear-area security as part of relief-in-place. These examples highlight cavalry’s differences in experience from their infantry or SOF counterparts.

In recent operations, Army’s cavalry has augmented multinational cavalry-led battlegroups, infantry battlegroups and engineer battlegroups, and it has also operated within military-led training schools. Cavalry sub-units have both led and supported joint and combined arms commanders. Cavalry has also provided commanders to multinational task groups.[26] Most recently, a cavalry battlegroup augmented the 2nd/14th Light Horse with ‘A’ Field Battery Royal Australian Artillery for reconnaissance purposes on Exercise Diamond Run 2024. The 2nd Cavalry Regiment also successfully integrated with a sub-unit from the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR) for pathfinding activities in 2023–24, and augmented a French mounted reconnaissance and surveillance squadron on Exercise Talisman Sabre 2025.[27]

Key Takeaways

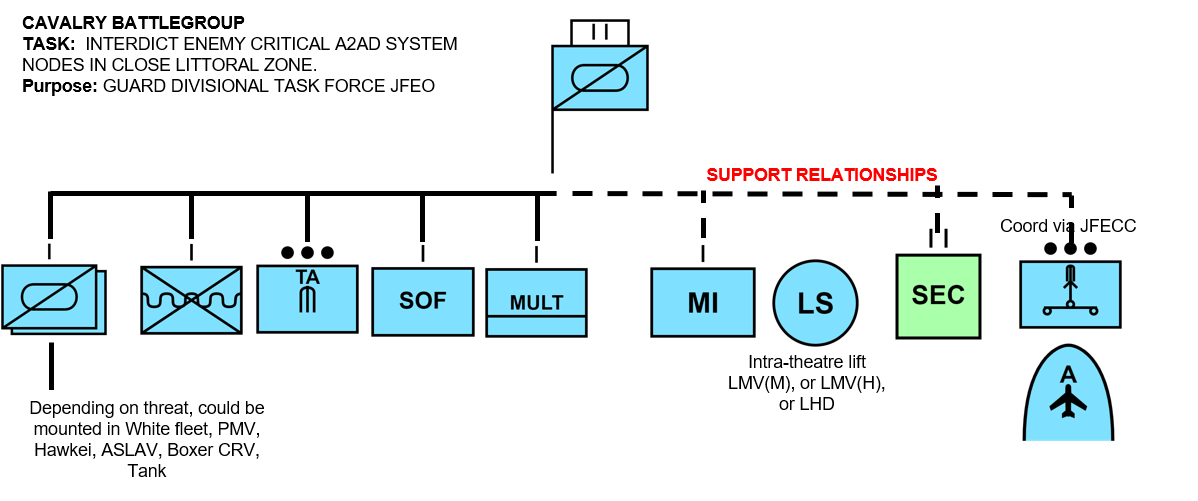

Cavalry offers strategic and operational planners with a deployable capability that can integrate readily with land, air or sea capabilities with a high degree of modularity. A cavalry battlegroup can operate as a whole, or can potentially subdivide into 36 patrols as part of a hub-and-spoke approach to dispersed littoral forces responsible for ISR and interdiction. In the littoral environment that characterises the Indo-Pacific region, this is a remarkably useful capability. Cavalry can be utilised in the early phase of an operational deployment as part of a meshed ISR network. Simultaneously, it can also disrupt an opponent attempting coup de main activities or large-scale amphibious operations by protecting and escorting missile posts around an island chain, or raiding enemy beachhead lines following amphibious operations. In this regard, parallels can be drawn with the operations conducted by 2/2nd IC in World War II when it raided the Dili defences, ambushed Imperial Japanese Army patrols and integrated with local nationals.[28]

Challenges and Opportunities

Cavalry has two main challenges to fulfilling its role in a modern context. These are the lack of a distributed and networked joint digital battlefield management system across the integrated force, and a lack of contemporary simplified doctrine that explains cavalry’s enduring and specific contemporary value to force designers and joint operational commanders who lack cavalry familiarity.

A digital battlefield management system is a command, control and communications (C3) support tool that assists with current and future force employment. To be effective in Australia’s contemporary operating environment, such a system must be capable of informing the relevant commander of the location of all friendly forces within the area of operations and interest (colloquially known as ‘blue force tracker’). Further, it should be able to simply transfer operational information (such as operational overlay depictions and orders via text) and it should be able to identify and prosecute enemies and conduct terrain analysis using modern tools such as artificial intelligence (AI). Cavalry, however, does not currently have an automated system that supports it to identify the location of joint forces in the battlespace. Without a (portable) tactical and operational-level C3 system capable of AI-driven threat and terrain analysis, or automated joint force tracking, the cavalry is often reliant on manual tracking and analytics. Information transfer is relegated to less contemporary methods such as radio communications.[29] While this can be adequate in austere settings where rapid information transfer is not required, in joint operations-particularly those conducted in archipelagic settings between dispersed littoral groups-this deficiency means that cavalry cannot optimise its capabilities.

Cavalry doctrine has become significantly outdated. Whereas modern cavalry operations have the potential to influence operational-level joint decisions, cavalry doctrine is based on contributions to single-domain (land) operations. Without contemporary doctrine that reflects the diversity of functions that the cavalry can achieve, it is routinely misconstrued by joint force designers and operational commanders as an organisation defined by the type of platform it operates (platform-centric organisation) or as a capability limited to reconnaissance and surveillance activities or ‘light tank duties’. While cavalry would likely demonstrate its utility post-deployment, three remedial steps are available to increase cavalry’s utility within its defined role. These are outlined below.

Communications

Cavalry needs joint and combined battlefield management systems that provide the highest possible echelon and coalition augmentation. Cavalry must be able to communicate effectively to share complex information with all-domain combined forces. It should be able to ‘plug and play’ with all allied nations using simple communications technologies suited for operations conducted in austere environments-including low bandwidth volume. Military operations currently in Ukraine provide valuable lessons on how capabilities can be leveraged within civilian networks to decrease detection and increase utility.[30]

Supply

Where possible, cavalry should streamline its classes of supply demands as generically as possible to reduce the specific burden of cavalry augmentation. While this may not be possible for some of the more bulky cavalry-specific items (such as tyres for the combat reconnaissance vehicles (CRV)), cavalry could pursue a uniform approach to auxiliary ammunition natures, combat ration types, uniforms, and individual protective equipment.

Doctrine

RAAC must update its doctrine and integrate itself better within relevant ADF joint doctrine. Cavalry must be able to articulate the ways, needs and means with which it operates in a way that is readily understood by members of a tri-service and military-civilian integrated workforce. A useful starting point would be to refer to the RAAC collectively as cavalry (light, medium and heavy) and refrain from the tank versus cavalry bifurcation. Accordingly, references to employing armour should be replaced with terminology focused on the employment of cavalry.

Cavalry’s Rapid Adoption of New Technologies, Tactics and Procedures

For innovation and adaptation to occur, an organisation needs sufficient stimuli (normally an acknowledgment of a limiting factor an actor cannot overcome). These stimuli may include demonstrated deficiencies in the range or depth of existing capabilities, challenges within the industrial base, or expected changes to the operating terrain. The impetus could also include the existence of sufficient resources and the presence of an organisational ethos or mindset (proactivity, creativity, risk-tolerance, collaborativeness) to support change. Cavalry possesses all of these stimuli. Much like 2/2nd IC’s approach in Timor, the mindset of those within the cavalry generally works from a position of relative inferiority. The handmade radio ‘Winnie the War Winner’, built from car parts, aerial wire, broken commercial equipment and a rope loop crank, stands proudly in the Australian War Memorial as a testament to 2/2nd IC’s commitment to solving potentially insurmountable problems with an innovative use of technology.

The modern cavalry has demonstrated its ongoing willingness to pursue operations and activities with new and improvised technology. A good example is the recent collaboration conducted between the School of Armour and Army’s Robotic and Autonomous Systems Implementation and Coordination Office (RICO), which examined tactical human-to-robot-teaming.[31] Relatedly, the School of Armour is currently instructing all current and future initial employment trainees on the medium-range uncrewed aerial system. It is also instructing on a strike-ready first-person view drone, man-portable surveillance and target acquisition radar, counter-UAS drills (incorporating specific shotgun and machine gun training), and modern mounted and dismounted cavalry tactics.[32] The School of Armour’s streak of foresight is also evident in the school-led decision to retrofit the Harris ANPRC/158 into the Australian Light Armoured Vehicle (ASLAV), which will provide a workable communications solution with old equipment-a ‘Winnie the War Winner’.[33]

Within the cavalry, technology assimilation is a high priority, including at the regimental level. For example, the 2nd Cavalry Regiment’s incorporation of the Paret and Puma UASs, as well as radar, is underway. In addition to demonstrating the technical capacity of RAAC personnel, this development shows the tactical capacity, as these systems transform the way that troop-level reconnaissance and surveillance is conducted. At the time of writing, the 1st Armoured Regiment is midway through optionally crewed vehicle trials to provide the ADF with versatile operational response options including resupply, casualty evacuation, fire support, obstacle breaching and other effects, mimicking the remainder of the corps’ technical capacity to learn new and complex systems such as the M1A2 Sep V3 tanks and the Boxer CRV.[34] Casting back to the experiences of the 2/2nd IC, the modern cavalry can provide joint force employers with ammunition packhorses to cross a river, a mobile hasty ambush platform, an indigenous force medical vehicle, a missile close protection capability, or a surf zone resupply vehicle. The possibilities are limited only by the imagination.

Tactically, cavalry’s recent combined arms activities demonstrate the its success in integrating forces-much as 2/2nd IC did with the remnants of Sparrow Force. In addition to conducting routine brigade activities, over the last 12 months the 2nd Cavalry Regiment has also integrated its surveillance troop with 7 Signals Regiment capabilities, integrated its sabre squadrons with commando elements, supported the 2nd Battalion’s amphibious activities, and provided some limited interoperability with the Regional Force Surveillance Group (RFSG).[35] The 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment and 1st Armoured Regiment have performed similar activities with Army units beyond their usual formation. This includes the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment training with the 51st Far North Queensland Regiment on mounted (manoeuvre) weapons ranges in 2024, and training with the 22nd Commando Regiment in 2023.[36] Similarly, the School of Armour’s Exercise Gauntlet Strike, conducted during the Regimental Officers Basic Course, culminates with a high-tempo 24-hour-a-day live-fire multi-combat team activity with cavalry (heavy and medium), infantry, engineer breaching and offensive support capabilities, all supported by versatile logistics.[37] During these activities, the regiment has successfully trialled new tactics, techniques, and procedures, echoing the adaptive edge of 2/2nd IC’s early successes.

Key Takeaways

With cavalry, the strategic and operational planner has a capability primed for innovation and adaptation, supported by adaptable and innovative capabilities, means, and mindset. A planner could deploy new technology within an already deployed cavalry unit to generate specific stressors that can test the technology and trigger upgrades. The 1st Armoured Regiment’s relationship with other cavalry units optimises new technology trial and rapid introduction into service. It also has the adaptability to retrofit capabilities and associated tactics in the field.

For the tactician, cavalry represents a capability that is comfortable with augmentation-a point further discussed in a later section of this paper covering combined arms. The same is true for new technology. Want to modernise the ability to orient a commander to a threat with a new flying widget? Sure, give it to a unit designed to orient the commander. Want to modernise an approach to autonomous distributed logistics? Sure, give it to a unit that routinely operates dispersed and trains in multi-echelon logistics from ab initio forward. Want to emplace a new widget on a vehicle that makes it hide better in a specific spectrum? Sure, give it to a unit operating forward while remaining undetected-the cavalry.

Challenges and Opportunities

Cavalry’s challenge is to influence the design principles used to generate collective training serials. Because of fiscal limitations across the ADF, it needs to achieve this while still adhering to the collective training metrics that shape ADF force preparation, force posture and force structure decisions. If successful in this effort, cavalry has the potential to ensure that new technologies are integrated with both old and new techniques and procedures. In this way, cavalry can provide platforms from which Army can employ not only new equipment but also old equipment used in new ways-a fundamental aspect of asymmetry. To support this effort, cavalry must pursue three associated lines of effort.

Collective Training

Cavalry should design and advocate for collective training serials that stress new innovations and that seek adaptations to optimise their utility to Army. Scenarios must be complex and challenging-it is no longer enough for a scenario to quickly descend into a 3:1 pitched battle. Scenarios should instead deliberately place the friendly force at a disadvantage, fighting for information, perhaps in a seemingly unwinnable situation but supported by modern doctrine. Such scenario design should include imposed resource restrictions in the planning and execution phases (both disclosed to the force and undisclosed). It was obstacles like these that were the catalyst for innovation and adaptation within 2/2nd IC in World War II when it restored operational communications, re-established air-to-ground strike coordination, and bolstered partner force morale.

In simulation and field training conducted at the Combat Training Centre, brigades and staff already prioritise innovation and adaptation metrics over measures that prioritise victory or defeat. Their focus is on the achievement of learning and adaptation loops rather than asking, ‘Did you win your pitched battle?’ Cavalry should follow suit. The outcomes of collaborations, such as the partnership between 1st Armoured Regiment and RICO, need to be tested in field conditions, providing feedback that may complement or contradict working assumptions made about the characteristics of modern operations, or that highlight new challenges that had not previously been foreseen. This mindset primes cavalry units to maximise new technologies and think differently about old ones.

Military Education

The professional military education (PME) undertaken by members of the cavalry should include a deliberate focus on creativity. Cavalry should work with challenging future scenarios that envisage the augmentation of emerging technologies and even those that only currently exist in science fiction-particularly when the exercise control gives a superior technology to the training adversary. PME should also include historical counterfactual scenarios to merge historical awareness with an adaptive focus. Such activities would promote new thoughts and ideas about complex problems while meeting the Chief of Army’s desire for improved military history acumen.[38]

Personnel

Cavalry should advocate to retain the 1st Armoured Regiment’s Commanding Officer, Officer Commanding, and some Warrant Officer positions as being RAAC-coded. While this is not a slight on other corps professionals, the RAAC’s size and personnel familiarity, combined with the cavalry’s unique role, context, and battlefield position, offers unique perspectives. These perspectives promote successful testing and evaluation, subsequent spiral upgrades, and employment of capabilities by a force possessing a unique ethos that seeks to achieve asymmetric effects with an economy-of-force mindset. Cavalry’s flexible force structure can readily adapt during periods of accelerated innovation, mitigating the need for Army to redesign its battalions and fires regiments until absolutely necessary.

Factors of Asymmetry-Disproportionality

In the context of asymmetric warfare, the term ‘disproportionality’ refers to the imbalance between the scale, intensity and type of relative response offered by the actors. During World War II, 2/2nd IC distinguished itself from its compatriots in the independent company and archipelagic barrier force by its capacity to achieve disproportional battlefield effects.[39] While questions remain about the ultimate strategic value of the Timor campaign, 2/2nd IC undoubtedly provided the SWPA high command with increased strategic options (and therefore achieved a strategic disproportional offset). Should it have wished to seize Timor, 2/2nd IC offered a capable pre-landing force that was already ashore. The presence of 2/2nd IC also helped to focus Imperial Japanese efforts on planning to extinguish forces on Timor at the expense of other operational-level activities in the theatre’s (and war’s) critical year.[40] For a middle power in a great power competition, the flexibility offered by capabilities such as the 2/2nd IC is essential in protecting strategic decision space and in supporting negotiation efforts among stakeholders that account for both unilateral and combined interests. More broadly, the successes of Winnie the War Winners likely boosted national morale for a continued war effort when Australia otherwise had few successes to celebrate.[41]

Tactically, 2/2nd IC achieved disproportionality by causing hundreds of Imperial Japanese casualties for comparatively low Australian losses.[42] This effect was largely achieved through 2/2nd IC’s application of mission command. For example, despite its ambiguous order to ‘Hold Timor’, it was able to apply its combined arms competence to win battles with personnel from multiple disciplines and trade skills-including retrained dentists, butchers, bakers and refrigeration mechanics.[43] It took relatively little effort to resupply 2/2nd IC compared to the Imperial Japanese Dili garrison forces, particularly after the Imperial Japanese shipping and air transport losses in 1942, which began to turn the operational tide.[44] Today, cavalry offers the potential to deliver disproportional battlefield effects through its multi-echelon familiarity and competence, its capacity to generate operational tempo, its application of mission command principles, and its combined arms competence.[45]

Cavalry’s Multi-Echelon Competence

The capacity of the modern cavalry to achieve operational competence across multi-echelons is attributable to a history of continued evolution in its form and function. Drawing on the history of Australia’s armoured forces in World War II, Australia raised and operated forces from the armoured division to regimental-level armoured support for an infantry brigade’s manoeuvre.[46] Similarly, Army’s cavalry regiments successfully provided simultaneous support to brigade and divisional formations (including deployed battlegroups from other brigades) before several units amalgamated, and subsequently, the 2nd Cavalry Regiment transitioned to an armoured cavalry regiment, focusing on brigade operations.[47] More broadly, cavalry and cavalry-like forces provided army-level, corps and divisional support during World War II. Demonstrating its ongoing adaptability, over the last four decades the 1st Armoured Regiment has successfully transformed from a mechanised brigade’s armoured regiment with a divisional focus, to a mechanised brigade’s integral armoured regiment, to an armoured cavalry regiment generating capabilities for battlegroup actions. It has operated as the chief firepower component of the 1st Australian Task Force and the 1st (Mechanised) Brigade and it has provided sub-units and troop-sized elements for special and conventional operations in Australia’s multi-decade commitment to the Middle East and Afghanistan[48]- an experience analogous to 2/2nd IC’s post-Timor reallocation.[49] Over the last decade, cavalry force elements have serviced interdepartmental, joint, divisional, brigade and battlegroup commanders’ critical information requirements (CCIRs)-much as 2/2nd IC’s reconnaissance activities focused on Imperial Japanese resupply on some days and facilitated tactical ambushes on others.[50] The 1st Armoured Regiment is now transitioning to an experimental unit to deliver and integrate emerging technologies.[51]

Throughout its history of operational service and other activities-whether as light, heavy or mixed forces-cavalry has successfully demonstrated the ability to support several echelons simultaneously and also to quickly transition the same forces from the unique tasks and perspectives of one echelon of command to another.[52] A cursory glance at the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment’s commitment to Afghanistan provides an example of troop-sized forces supporting United States Special Operation Detachment Alphas in one operational-level effects mission before immediately pivoting to support Australian battlegroup tactical-level conventional operations in the next.[53] The 2nd Cavalry Regiment’s pivot from a northern Australian exercise to prepare for Operation Plumbob (Solomon Islands) is another.[54] In the modern context, these experiences, and the skills developed from them, are essential to provide Army with sufficient operational flexibility.

The modern battlefield is more complex than at any other time in history. For Australia, the geography of the littoral domain within the PAMI, the dispersed nature of archipelagic manoeuvre, the unreliability of secure communications, and the range, speed and lethality of modern battle systems pose almost insurmountable challenges. Forces employed to perform the primary blocks of command and control-sense, decide and act-must be able to orient as a vertically and horizontally nested mesh system. A mesh system involves a mindset and network architecture where each force (or node) can connect directly to the others, without the need for a central hub. This mesh system must have the capacity to respond to tier-one adversaries with speed, precision, decision superiority, and credible deterrence or lethality.

Given Australia’s modest operational and strategic lift capabilities, it may be difficult to swiftly reinforce already deployed force elements in response to the short-notice escalation of crisis or conflict. So forces already deployed (on operations or on exercise) forward of Australia’s shores must be credible, capable of capitalising on opportunities as they arise, and able to address any immediate gap in military capabilities. This might require the rapid regrouping or reorienting of force elements under a different command echelon. Such an approach would optimise Army’s utility across the competition-to-conflict spectrum. This was something the brave but unfortunate 1941–42 Malay and Netherlands East Indies archipelagic barrier forces were unable to achieve once their strategic American-British-Dutch-Australian Command disintegrated.

Key Takeaways

Cavalry offers the strategic planner, operational planner and force designer a force armed with immediate and latent capabilities across different echelons of command. Due to its training, cavalry can simultaneously monitor several echelons’ CCIRs, their depth of networked communications and their manoeuvre speed.[55] Given certain preconditions, the cavalry force can also regroup, reorient to higher or lower echelons and generate potent response options. This can be achieved without direct contact with an adversary. With a sufficient commitment of forces (such as a cavalry battlegroup headquarters), the same cavalry unit could operate at different echelons simultaneously. For adversaries seeking to identify Australia’s critical vulnerabilities across various levels of command, such operational flexibility poses problems. Being unaware of a cavalry unit’s access to a particular fire unit, and which commander’s CCIRs are being serviced, the adversary may, at the very least, have reason to pause and commit further ISR capabilities. At best, the uncertainty generated may temporarily deter hostile action.

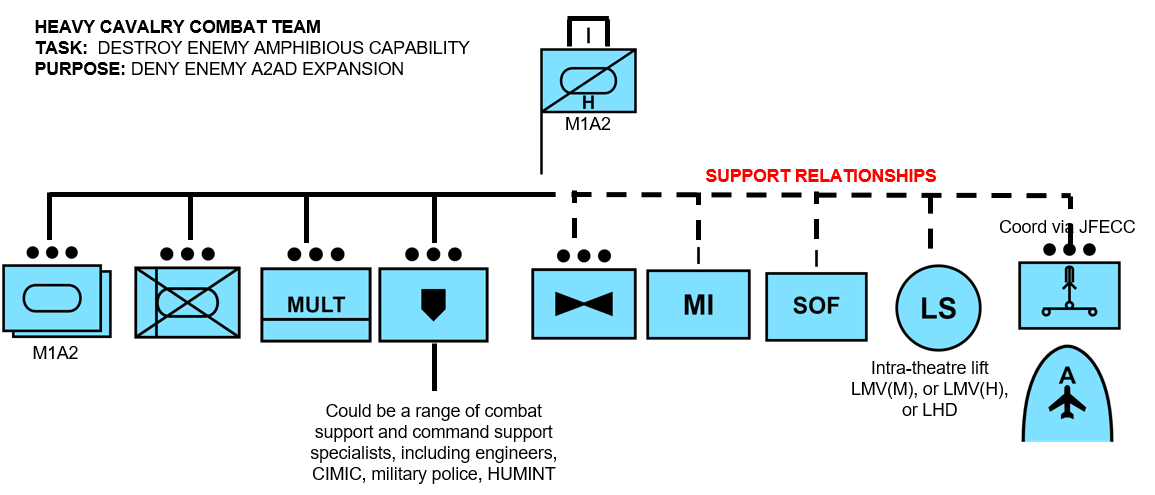

To further underscore the multi-echelon competence embodied by cavalry, the following examples are instructive. A cavalry unit has the flexibility to have the regimental headquarters and at least two sub-units operating as the bulk of a task force’s (divisional size) littoral interdiction/covering force. Simultaneously, it can have a detached sub-unit operating as a task group’s (brigade size) primary strike or counterattack force (armed with tanks, joint targeting assets, littoral lift, and access to long-range fires capabilities), as well as one sub-unit split down to troop level. This formation could provide security forces for three fires-based task units (regiment or battery size) as part of land control efforts or to deny an adversary access to a sea chokepoint.

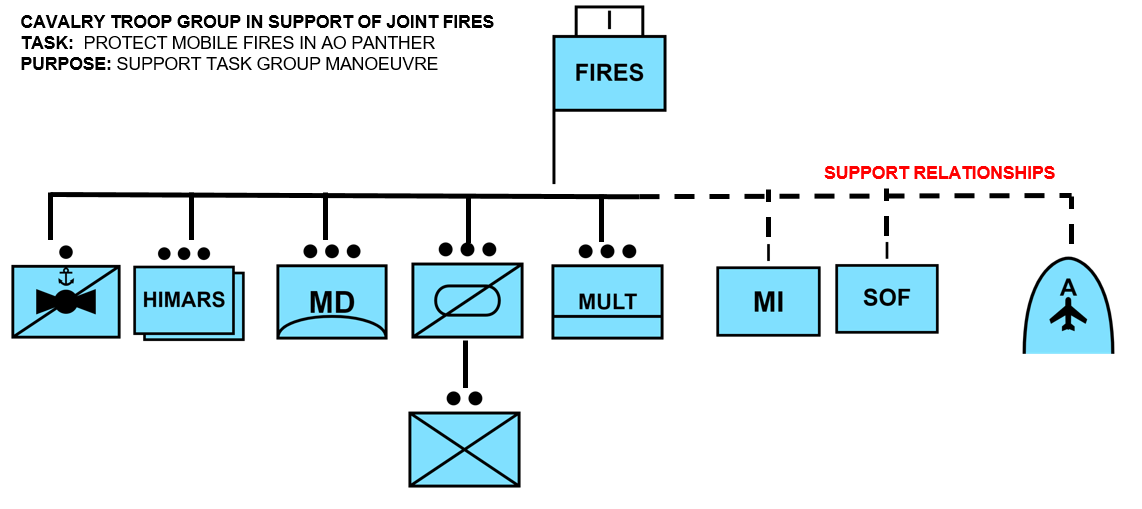

Cavalry’s doctrine provides several indicative examples of cavalry-led combined arms force structures. For illustrative purposes, figures 3 to 5 provide contemporary examples relevant to the littoral domain.

Challenges and Opportunities

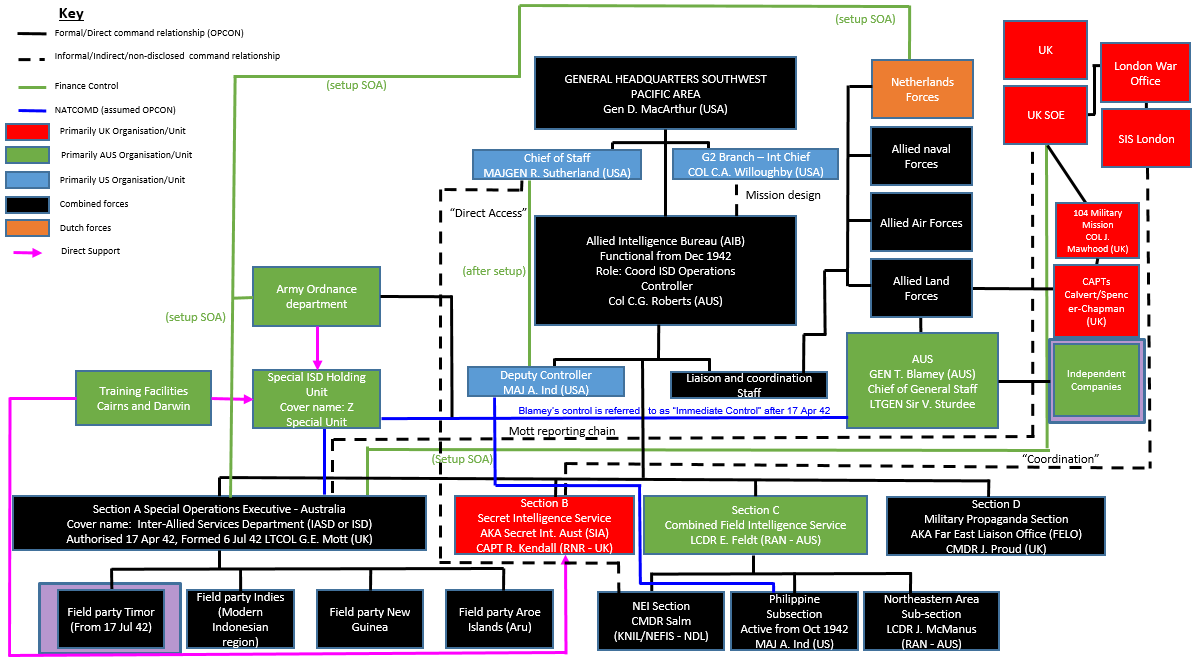

The Timor 1941–43 case study is an excellent example of a campaign that failed to capitalise on the cavalry ethos of having a singular unit capable of multi-echelon support. Instead of training and deploying a force capable of both, the Australian strategic-level hierarchy designed and trained the independent companies and SOE-A forces separately. Figure 6 demonstrates these forces’ separate chains of command and the position of their hierarchy, with the author’s interpretation of formal and informal command relationships displayed. The violet squares highlight the two units deployed to Timor. Both units had separate reporting chains, which generated inefficiencies and insufficiencies in intelligence collection and dissemination. Both units had separate logistics methods, chains and echelons, generating combined inefficiencies and degraded interoperability. Both units had related but separate objectives that impeded strategic and operational phase synchronisation and placed pressure on the demands of the Timorese partner force. Rather than following this model, cavalry should seek to demonstrate asymmetric competence through multi-echelon support. There are four elements to this endeavour.

Military Education

Military education should more deliberately school members of cavalry in the challenges and opportunities afforded by simultaneous echelon support. Military history provides several relevant case studies, some more successful than others. These include the World War I operations of the Desert Mounted Corps and TE Lawrence’s cavalry in General Allenby’s Sinai and Palestine campaign; the planned simultaneous multi-echelon cavalry support provided to the Pentropic Division in the 1960s of an independent cavalry regiment and also a divisional ‘Recce Squadron’-read cavalry. It also, naturally, includes the operations of the Independent and Cavalry Commando regiments in Papua and New Guinea in World War II. The cavalry’s operations in the United States Civil War and the Seven Years War provide further examples. At institutions such as the Land Combat College and the Australian Command and Staff College, presentations by officers with theatre- and operational-level coalition headquarters experience could highlight the battlespace management challenges that arose in such scenarios. This historical context could then help inform the training scenarios developed for contemporary units and formations, generating the sorts of realistic demands imposed on deployed forces when subject to, for example, intermittent loss of communication. Simulation activities and overseas staff rides to examine the World War II Cartwheel and Watchtower campaigns would provide further opportunities to explore the challenges imposed when force elements are required to provide simultaneous echelon support.

Doctrine

Updates to cavalry doctrine at both formation and joint levels must be informed by the collective cavalry experience of multi-echelon support. Valuable lessons exist from cavalry’s experience of transforming to divisional, brigade and bespoke task unit levels, both in and out of active operations.[56] These experiences should drive the revision of doctrine and standard operating procedure within Land Power, Campaigning in Competition, Campaigns and Operations, Targeting, Land Force Tactics, and Coalition Operations. It should also influence aspects of the ADF’s functional concepts and Concept Lantana.[57]

To facilitate this endeavour, cavalry units should engage expertise from within the Australian Army History Unit. Points of reference could include the experiences of key commanders during Australia’s military commitment to Vietnam, and during the reorganisation of the Army during Army’s several 20th century postwar reorganisations. Other areas of particular relevance to cavalry are the transformations that occurred within the 6th, 7th and 9th Divisional Cavalry to become Cavalry Commandos in World War II. In this regard, the friction that occurred during the transition from Independent Company to Cavalry Commando regiment, as well as the transfer from brigade- to corps-level troops, is particularly informative.[59] Elsewhere, the post-Cold War reorganisations of United States cavalry and Marine Corps formations help to identify gaps, friction and opportunities that can be pre-empted and remediated before commitment to combat.[60]

Plans

Cavalry should reinforce its collective historical understanding of the core plans developed by 1st (Australian) Division’s associated CCIRs-particularly as they related to the divisional commander’s priority intelligence requirements. Cavalry forces should pursue the same awareness within Australia’s five-eyes community and with those regional partners with which information sharing is appropriate. The focus should be on achieving a better understanding of Australia’s strategic military objectives across the PAMI as they relate to international engagement. This effort should be supported by routine collection activities and tasks issued by the respective campaign commander or task unit commander in addition to the cavalry unit’s parent brigade. Brigades might facilitate this endeavour by ensuring that cavalry teams are able to participate in regular regional engagement activities and allowing cavalry sub-unit headquarters to command expeditions wherever appropriate.

Partnerships-Allies and Partners

Cavalry should strengthen its reciprocal relationships with allied, partner and national units. One way to facilitate this would be by Army authorising cavalry’s involvement in intelligence and plans-sharing arrangements with elements outside of its immediate chain of command. This would require direct liaison authority to be granted by the relevant brigade commander. Such a measure would provide cavalry elements with the awareness necessary to inform force allocation and regrouping decisions and to participate effectively in broader international engagement efforts. In this regard, fostering a relationship with the United States’ regionally deployed civil affairs teams and partner-nation security forces should be a priority.

Special Operations Command (SOCOMD) is a particularly important relationship for cavalry. There are broad synergies between the functions of the Special Air Service Regiment, Australia’s commando regiments and Army’s cavalry units. As history has shown, the possibility exists that, on operations, battlefield responsibilities may be handed over from SOF to the cavalry.[61] During Operation INTERFET, for example, cavalry and special operations elements were routinely integrated, with considerable success. Further, on Operation Slipper II, cavalry augmented later rotations of the Special Operations Task Group. The prospect exists to capitalise on opportunities and operational-level efficiencies that were never realised between 2/2nd IC and SOE-A.

Tempo

Cavalry provides disproportional and asymmetric operational effects through the effective application of tempo. Tempo includes generating superior speed of (a commander’s) decision, speed of transition (between tasks), and speed of execution (performing the task). While cavalry facilitates each aspect of tempo, cavalry’s speed of transition is particularly noteworthy in the context of Australia’s current and expected strategic requirements.

Because of the breadth of operational capabilities that can be delivered by cavalry, it provides a unique value proposition to a nation grappling with the strategic challenges posed by a lack of military mass, a lack of technological overmatch to any tier-one adversary, and difficulties in projecting and sustaining force with the archipelagic territories that characterise much of the PAMI. On operations, cavalry forces are particularly competent in scouting and reconnaissance; providing flank security to main body activities; raiding enemy targetable critical vulnerabilities at short notice; surveillance; conducting limited offensive and defensive capabilities; and protecting and escorting vital assets such as long-range strike platforms. Simultaneously or in rapid succession, a cavalry unit can escort key diplomatic, strategic or operational capabilities over challenging land terrain, can train and assist host nation forces (with integral mobility), can reconnoitre key nodes for operational-level follow-on operations, can survey competitor or potential adversary assessed key corridors and terrain and can, if surprised, commence security, defensive and retrograde actions until a main body arrives.[62] It also possesses particularly well-developed cultural acumen in its dealing with allies and partners.

Other elements of Army are specialising to be more robust and relevant to the PAMI, at the cost of becoming less able to fill such a broad spectrum of roles. For example, the Royal Australian Regiment’s reorganisation of infantry to specific roles (including reconnaissance, armoured infantry, light littoral, and air portable/motorised) has had the effect of increasing its technical and tactical regional utility at the cost of its previous structural flexibility and functional depth. Bringing an infantry force offline for extended periods in order to conduct security and training support missions in times of peace costs it precious time that is better spent focused on developing its core warfighting expertise. In this regard, it is already harried. Over the next five years, infantry can expect to mechanise a battalion with infantry fighting vehicles for the first time ever (making it suitable for modern crisis and any form of modern conflict), to reorient its motorised and littoral units for new missions and terrain, to retrain its reserve capability for a 2nd (Australian) Division’s focused role (that changes reinforcement models) and also to provide instruction to partner forces in a range of scalable military activities beyond its existing PAMI commitments.[63] These functions, all essential to Australia’s survival, require significant training and expertise.

Unlike cavalry, most other reconnaissance and surveillance units conduct their tactical-level activities using restrictive insertion platforms such as riverine craft, helicopters, or UASs. By contrast, cavalry forces are generally qualified to use multiple insertion platforms, making them particularly valuable across the competition continuum. Current cavalry forces have both exercise and operational experience with several vehicle and platform types including the M1A1 and M1A2 Main Battle Tanks, ASLAV, M113, PMV, PMV(L) Hawkei, Land Rover, Boxer CRV, G Wagon, medium truck variants, civilian 4WD, micro-UAS, motorcycles and small boats (albeit the last two in limited quantities). The 2nd Cavalry Regiment’s current training program includes a deliberate effort to convert tank soldiers to ASLAV so they can work more effectively within regimental headquarters.[64] In competition, a cavalry force is as comfortable operating with host nation white-fleet vehicles as it is with an armoured vehicle. This assertion is supported by literature previously published by this author and Mark Sargent, and is validated by recent work conducted between both the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment and 2nd Cavalry Regiment with the RFSG, and on recent regional exercises conducted by cavalry elements in Malaysia, Tonga, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Solomon Islands.[65]

Key Takeaways

For force designers and planners at all levels, cavalry represents a capability that can deploy versatile forces within the continuum of global competition, with structural depth that can endure periods of extended competition. Drawing on the size of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment and the capabilities from the 1st Armoured Regiment, cavalry can deploy into operational theatres to rotate with like capabilities while simultaneously conducting force readiness activities back in Australia to maintain core competencies.[66] Cavalry can perform a range of operations including security and transition, as well as offensive, defensive and stability operations with remarkable economy of force. With a workforce distinguished by their competence across multiple platforms, a commander could task personnel who are deployed forward to collect and use vehicles delivered to them, without a need for a passage of lines. Far from being tied to one particular horse-‘the Boxer unit’ or ‘the tank unit’-cavalry troops can change, repair or enhance vehicles with ease.

Cavalry has the flexibility to rapidly change tasks while already deployed in theatre. For example, with the issue of a simple code word, a training team operating alongside host nation forces could switch tack to secure key operational terrain including, for example, seizure of an operational node. Historical precedent can be found in 2/2nd IC’s actions against the Imperial Japanese occupation of Dili. Having options like this supports the achievement of campaign and tactical tempo by enabling rapid decision-making, execution and transition. Supported by its relationship with the 1st Armoured Regiment in its new experimental role, cavalry augmentation with other combat arms can involve the introduction of innovative and disruptive technology to the battlefield. This has the potential to boost in-theatre capabilities without retraining, and can assist both Australia and partner nations to introduce new technologies quickly.

Challenges and Opportunities

The capacity for cavalry to realise its full potential is currently threatened by insufficient personnel within its force structure. For cavalry, the lack of integral dismounted scout capabilities means that cavalry commanders have to cannibalise sub-units to generate simultaneous mounted and dismounted effects (both are essential ingredients in cavalry manoeuvre). The same problem was faced by the 2/2nd and 2/4th IC in the second half of 1942, when platoons and sections were cannibalised to offset operational losses caused by enemy action and disease, slowing phase transition and increasing mission risk. A similar situation exists within cavalry today, limiting the durability and sustainability of its reconnaissance operations, which are a critical component of sustained littoral operations. The cavalry should remediate this issue through three lines of effort.

Exercises

The opportunity exists for cavalry to more effectively demonstrate the value of its operational and tactical-level contributions during command post exercises, simulation exercises, staff rides and limited-duration field training exercises. Cavalry must advocate strongly to cease the dangerous action that has crept into schoolhouses-abstracting the covering force battle, skipping the reconnaissance phase, or granting complete situational awareness to the tactician under assessment. Such an initiative would demonstrate to the ADF the value of a comparatively small cavalry-sized force in shaping the campaign without total force commitment in a situation of uncertainty. It would also help inform recommendations concerning the unit establishment review that are outlined in the next paragraph.

Unit Establishment Review

The 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment should continue to study the capabilities extant in 1st Armoured Regiment and under development in RICO to identify capabilities that can deliver reconnaissance effects with as few personnel as possible. For example, with a modest supplementation of operators controlling uncrewed ground vehicles (UGVs), lidar, radar and UAS, cavalry may be able to deliver disproportionate capability effects. To illustrate, one drone operator might replace the traditional 1990s-era two-person team needed to clear a defile. Similarly, two UGVs and two dismounted scouts might replace a scout section, and one lidar team might replace a whole surveillance section.

Partnerships-2 RAR

Cavalry should develop and enhance a routine training program with 2 RAR and the respective brigades’ infantry battalions. This will ensure that cavalry retains a dismounted reconnaissance expertise until it can be grown and managed internally. This measure will also provide the nucleus of training and experience to support any potential future force structures that might need a divisional cavalry element, a corps cavalry or a brigade cavalry establishment with cavalry scouts.

Partnerships-1st Armoured

Army should focus the 1st Armoured Regiment towards the cavalry units for trial and experimentation. Cavalry units should seek to augment 1st Armoured troop to squadron sized organisations within their current hollow order of battle structures.

Application of Mission Command

Cavalry forces routinely train in environments characterised by long distances, inconsistent communications, firepower under match, and fleeting opportunities for coup de main actions. All the while, cavalry balances risk against its requirements to achieve economy of force. While cavalry employs several techniques to negotiate this environment, the most relevant to this paper is the application of mission command. In broad terms, mission command refers to the philosophy of command and control that emphasises initiative, freedom of action, and decentralised execution. In both joint and integrated environments, the concept of mission command is often distrusted as an umbrella term that authorises Army to ‘do whatever it wants’. However, this perception is misplaced. Against a centralised foe, mission command supports tempo by enabling accelerated decision-making, positioning force elements to acquit resources economically, and ensuring that a commander has the appropriate touchpoints to allocate resources and to supervise the operation effectively.

The principles of mission command feature heavily in cavalry training. Early exposure to mission command is a core differentiator between cavalry and other arms corps. Early in their training, cavalry members are taught to recognise and apply ‘task verbs’, generally issued in a succinct set of radio orders, rather than long, highly prescriptive sets of orders. This forces cavalry soldiers to ‘fill in the gaps’ of how the mission is to be performed, stimulating creativity in design, initiative when things aren’t going to the visualised plan, and decentralised execution when quickly changing from a reconnaissance mission into a security one when the enemy counterattacks. At the ab initio level, a cavalry soldier’s first field exercise invariably exposes them to multiple facets of operational conduct, which imbue a unique situational awareness. These include the distribution and supply of various classes of logistics; the force preparation and force projection demands for mounted units traversing across Australia; the requirements for information and intelligence collection through reconnaissance; how to respond to formation-level control measures as part of command and control; how to integrate with other combined arms; and how to facilitate the generation and employment of information operations assets. Cavalry instructors expect trainees to develop experience and make sound judgements on the achievability of all aspects of planning and orders, including during course of action analysis, in the development of coordinating instructions, and when assessing the constraints and requirements that relate to administration, logistics, command and communication. With the ability both to describe the purpose and end state of any given mission and to understand what it takes to deliver on that mission using platoon-level combined arms, cavalry members have a level of shared understanding that is arguably unique across Army.

Cavalry’s grounding in the principles of mission command positions its members well to participate in the series of foundational career development courses that all arms corps members undertake. These include the rigorous Subject Four (Corporal), the Regimental Officers Basic Course (Lieutenant) and the Combat Officers Advanced Course (Captain), as well as combined arms exercises and operations. Because of the long duration of these foundational courses, familiarity is built between the trainees and instructors who, by the nature of the corps structure, are likely to become students’ squadron and battlegroup commanders in the future. Through this process, individuals with potential for future leadership can be identified from among trainees-much like what occurred during World War II when the throughput of the Commando School at Wilsons Promontory informed the selection process for leaders of the independent companies.[67]

Key Takeaways

Cavalry offers planners and force designers at the strategic and operational levels an option to deploy forces that can operate effectively without the burden of continual communications and supervision. This versatility reduces strategic risk to mission and operational effectiveness, particularly during periods of high tension or flashpoints between competition and crisis. Operational commitments to Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrate that cavalry is comfortable operating with significant responsibility at troop and section/patrol levels, meaning a section or patrol commanded by a sergeant or lieutenant can perform actions with low supervision and low risk to the mission.[68] This approach matches that of 2/2nd IC, which was characterised by a high officer ratio and by expecting responsibilities ‘far in excess of those normal to his rank’.[69] Equally, in cavalry a force designer gets a force with a high rank to low footprint size ratio, with high levels of maturity and experience. Such a capability can readily turn from a ‘sense node’ conducting surveillance in the operating environment, into a ‘deciding node’ which must make a significant operational decision such as whether to pre-emptively strike a potential threat when operating alongside partner militaries and civilian populations with sufficient restraint and tactical judgement.

In a situation of inter-state competition, a cavalry unit operating abroad as part of a training mission could simultaneously assist the host nation, generate route reconnaissance reports, recognise a key operational node’s vulnerabilities and opportunities, and establish relationships with personnel inside their area of influence as a matter of course -much as 2/2nd IC did on arrival in Timor.[70] This provides the ADF with a utility and versatility to offset its lack of mass and to reduce long-range logistics provision. A good cavalry headquarters has various contingency plans developed for possible follow-on missions.

Opportunities

Cavalry can optimise its value to the ADF with four actions that build trust in its abilities within the Defence hierarchy, both military and civilian.

Strategic Engagement

Cavalry should demonstrate its can-do attitude by positioning itself to participate more fully in strategic-level decision-making. It can be challenging to ‘secure a seat’ at the higher Defence echelons involved in force design experimentation activities-the sandpit of force design decisions. But it can nevertheless be achieved once the value proposition of cavalry to the ADF is more widely understood. A prerequisite to this is cavalry’s active participation in strategic and operational-level wargames and simulation when billets are offered. Relatedly, cavalry simulation activities should test the capacity of subordinate commanders to interpret and achieve strategic and operational-level objectives under realistic short-notice and high-pressure circumstances.

Staff Rides and Exercises

Cavalry units should build a library of staff-ride and tactical scenarios, both at home and abroad, which can be used by various regiments to conduct brigade-level activities. By advocating cavalry’s historical utility, including its flair and instinct (Fingerspitzengefühl) and its capacity to rapidly assess mission requirements (coup d’œil),[71] cavalry can position itself as the ADF’s force of choice within a rapidly evolving security environment characterised by strategic, operational and tactical-level ambiguity.

Military Education

The continuum of PME for cavalry personnel should focus on building cultural and regional acumen. This should include developing awareness of Australia’s multi-domain geography, regional anthropology, and demography. Cavalry personnel should also be encouraged to reflect on the fundamentals of human psychology such as cognitive bias, critical thinking, and self-awareness. This knowledge will optimise cavalry for the physical, informational and human terrain that characterises the PAMI. While many cavalry personnel develop such acumen through informal study, learning remains ad hoc.

Partnerships-Arms Corps

Unit-level cavalry commanders should continue building relationships with their peers across formations through mess culture, through contributions to PME programs, and by becoming familiar with a range of combined arms doctrinal publications. Cavalry should also continue to advocate for its incorporation in brigade and divisional collective training design in Army Training Level (ATL) 4 of Army’s Collective Training Design: Army Training Management Framework as a matter of course-whereas the author observes that recently, cavalry has frequently only been incorporated beyond ATL 5.[72] Practically, cavalry can achieve this by blending the competencies derived from unit-level ATLs with those of other brigade and divisional units. Such activities create the foundation for familiarity and trust, and set the platform for improving Army’s platoon-level combined arms competence.

Combined Arms Competence

Cavalry recognises that it integrates well with combined arms teams, regardless of whether it is operating defensively or offensively. At the tactical level, cavalry is as familiar with supporting an infantry brigade attack as it is with escorting and protecting a mobile fires unit targeting an opponent’s over-the-horizon amphibious vessels. At the operational level, cavalry personnel have training and experience in the many facets of campaign planning; operational-level manoeuvre; resource distribution and logistics; operational-level reconnaissance and surveillance; command and control; joint operations synchronisation; civilian-military integration; targeting and fires and effects; and information actions.

Over the last decade, instances of integral (RAAC) dismounts to the cavalry unit have waned. But this situation has forced cavalry to strengthen its relationships with infantry reconnaissance troops, direct-fire support weapons teams, regular infantry, and combat engineers below troop level. The result is that cavalry can now claim combined arms competence at the lowest manoeuvre brick (the section/patrol) and a deep familiarity with combined arms teams. Like their infantry counterparts, cavalry routinely integrates joint fires teams and joint terminal air controllers into their sub-units. In recent history, United States armoured cavalry regiments have demonstrated particular finesse at integrating joint and land fires into their organisations. This topic could furnish a paper in its own right, but suffice to say that cavalry group combined arms competence is a foundational competence for all multi-domain task forces of the future.

Key Takeaways

With its combined arms competence, the range of functions that cavalry is able to conduct is remarkably broad. Examples can be summarised as follows.

A cavalry-centric ready battlegroup is a smaller workforce size than an infantry battlegroup with many of the same capabilities, albeit with cavalry’s inherent economy-of-force limitations.[73] By using such a formation, the operational planner can preserve infantry battlegroups to conduct unlimited offensive and defensive actions if and when required. In the littoral environment, preserving this capability is vital, particularly if Australia fields the smaller force. In this regard, it is worth reinforcing that Australia’s infantry battalions become critically important in generating relative superiority in the first stages of a conflict, so operational planners should be careful to avoid committing them too early-particularly Australia’s most potent land capability, the armoured and armoured infantry battlegroups, consisting of the bulk of Australia’s tanks and infantry fighting vehicles.

A cavalry-centric ready combat team conducting operations as part of a ready battlegroup can conduct vital asset counter-penetration or in-contact passage of lines. The speed with which this can be effected may be critically important to forces operating with mass or technological undermatch.