Although infantry commanders throughout the Marine Corps have now had an opportunity to see the combat effectiveness of light-armoured infantry (USMC LAV regiment now titled Light-armoured Regiment) units through the full range of conflict intensity ... many do not understand the mission, function, capabilities, limitations or proper methods of LAI employment.

- Captain J. J. Maxwell, US Marine Corps,

‘LAI: Impressions from SWA’, Marine Corps Gazette, August 1991.

On the subject of light armour, the author admits to experiencing the same frustration felt by Captain Maxwell. It is encouraging, however, to note in 2004 that the US Marine Corps appears to have a better understanding of the use of a light-armoured cavalry capability than it did when Maxwell wrote in 1991. A 2003 Marine Corps document on lessons learnt from Operation Iraqi Freedom states that the mounted light-armoured regiment (LAR) has the potential to be ‘the most lethal [and] versatile force on the battlefield’. 1

Unfortunately, the Australian Army has yet to reach a similar level of comprehension about the value of its own Australian light-armoured vehicle (ASLAV) as mounted cavalry. Despite fielding arguably the best light-armoured vehicle in the world in the form of the ASLAV-3, developing robust doctrine for its use and generally leading the way in light cavalry thought and tactics for fifteen years, the Army still underestimates the potential of its own cavalry. The reasons for this underestimation are twofold. First, the Army possesses only one modern ASLAV cavalry regiment based in faraway Darwin. Second, there is a limited focus on cavalry in Australian military education and training. As a result, the role of cavalry in Australian military culture is ambiguous and does not fit easily into any particular conceptual framework. Yet, as we enter the Hardened and Networked Army (HNA) initiative—an initiative aimed at improving our combat firepower and protection—we must develop a better understanding of our organic light-armoured capabilities.

The purpose of this article is to explain how ASLAV mounted cavalry, operating as part of a combined arms team, provide a multipurpose and combat organisation that is ideally suited for employment on the complex battlefields of the 21st century. Indeed, the ASLAV meets many of the Chief of Army’s Development Intent for HNA organisation as outlined in the ‘Complex Warfighting’ operational concept. The Chief of Army has directed that ‘all elements of the deployed force are to be provided with protected mobility, firepower, situational awareness and stealth to enable them to perform their missions without undue risk’. 2 The HNA of the future is to be optimised for close combat in complex terrain as part of a joint inter-agency taskforce. HNA elements must be capable of medium-intensity warfighting in a coalition setting and be adaptable to peace support operations.

The problem that the Army faces is that, when it comes to the employment of cavalry, the Australian Army clings to an edifice of mythology. This mythology has inhibited constructive thinking about the use of ASLAV across the spectrum of conflict. If the land force is to create a modular and flexible force in the future, this mythology must be overturned and replaced by reality.

Cavalry Capability 'Bricks'

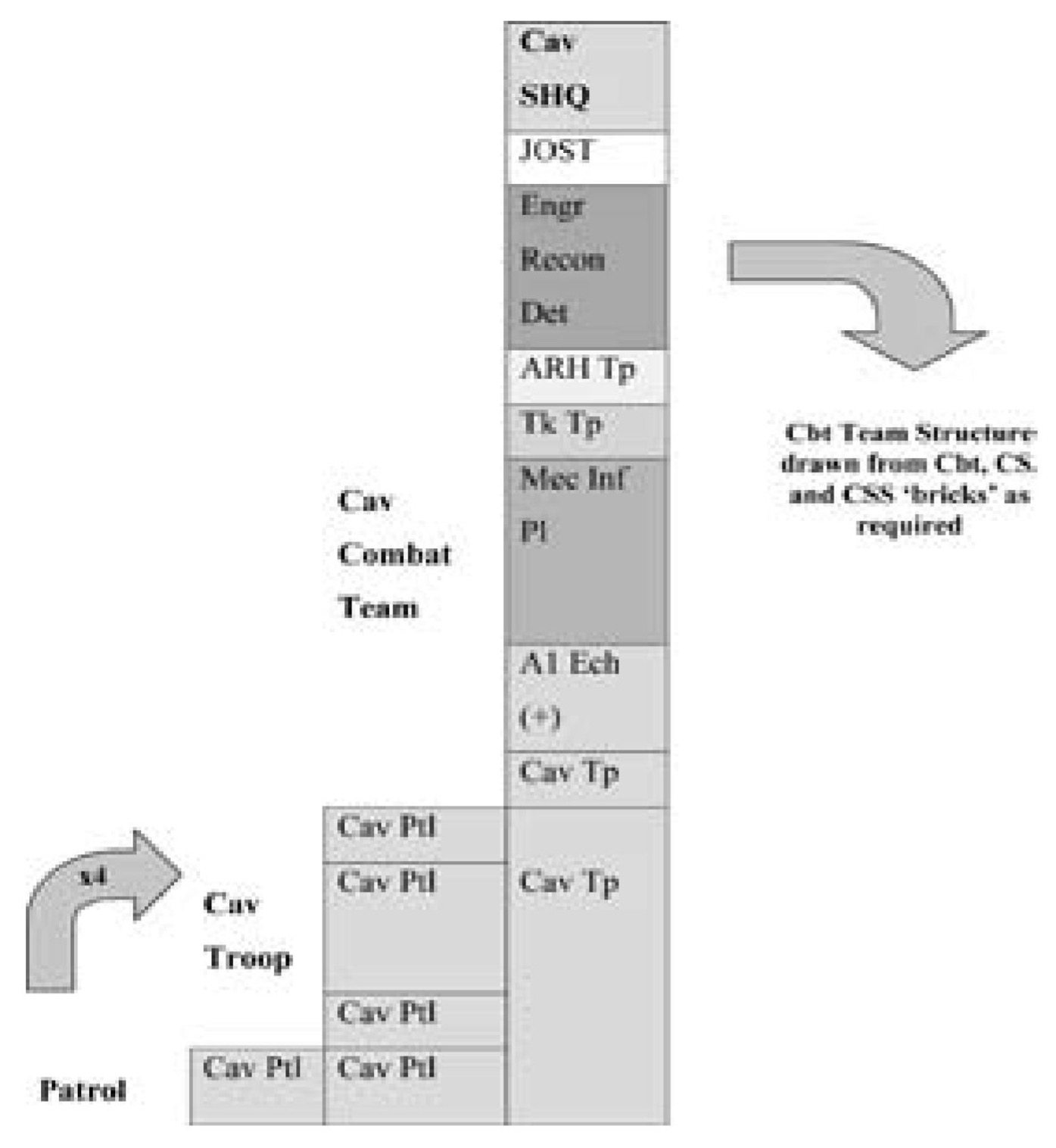

The ASLAV cavalry regiment is modular and fights according to its organic combined-arms team organisation—that is, by patrol, troop, squadron and regiment. The diagram at Figure 1 below represents the cavalry action that can be generated at each level of activity.

The basic capability ‘brick’ of the regiment is the three-vehicle patrol composed of two ASLAV-25s, one ASLAV-PC, and a four-man dismounted cavalry scout patrol. To appreciate fully the inherent versatility of this organisation, it is essential to understand the capabilities of both the vehicle and the dismounted troops.

The vehicle patrol is mounted in an ASLAV-3. The latter is a highly mobile armoured vehicle that can be deployed by air, land or sea. For its part, the ASLAV-25 incorporates a fire control system, with LAZER and autolay functions that are similar to those found in modern main-battle tanks. The fire control system includes magnified thermal optics; a highly accurate, stabilised 25 mm cannon; a 7.62 mm coaxial machine gun; a flex-mounted 7.62 mm machine gun; and a 76 mm grenade launch system. The ASLAV-PC is fitted with a non-stabilised .50-calibre machine gun. All Australian light-armoured vehicles are fitted with Global Positioning Systems (GPS), an Intra-Vehicular Navigation System (IVNS) and a digital VIC3 radio harness capable of supporting secure high, very high and ultra-high frequency radios.

Figure 1. ASLAV Cavalry Regiment by Patrol ‘Brick’ Structure.

Note: 1 x Cav ptl (Patrol) = A 3 x ASLAV Vehicle Patrol or 1 x four-man dismounted team.

By the end of 2004, all dismounted cavalry scouts will be equipped with secure high and very high frequency radios, Javelin direct-fire support weapon, a Thermal Surveillance System (TSS), unattended ground sensors (UGS), plus NINOX, GPS, and LAZER range-finding binoculars. While the patrol is the basic cavalry ‘brick’, the troop represents the lowest-level ‘brick’ available for sustained operations or cross-attachment to another manoeuvre unit. The present cavalry regiment consists of three squadrons of twelve patrols that generate a total of thirty-six-patrol ‘bricks’ (or nine troops) for creating task-organised combined-arms organisations.

How Cavalry Fight

Modern Australian cavalry fight the same way and conduct the same range of tasks as traditional cavalry or light horse. The difficulty faced by cavalry advocates inside the Army is that few outside the realm of mounted operations understand the character and scope of the modern cavalry’s role as a highly mobile, multirole combat organisation across the spectrum of conflict. Modern Australian cavalry fight either mounted or dismounted in a broad range of reconnaissance, offensive, defensive and security missions. 3

Even at the lowest level—that of the patrol—cavalry operate as a networked, mobile and protected unit equipped with excellent day-and-night optics and with a capacity to fight either dismounted or mounted, as circumstances dictate. This combination of patrol capability means cavalry units are ideally structured for uncertainty, with the cavalry team representing a hard target—hard to find and fix, hard to hit, hard to penetrate. The cavalry team is also capable of immediate retaliation at ranges of 3200 m, employing considerable firepower and precision accuracy. Cavalry elements can execute multiple tasks by day and night—ranging from searching buildings, communicating with local populaces, distributing food and aid to engaging enemy conventional forces. Such tasks can be completed without a need to regroup or be reinforced by other manoeuvre units.

Because of its inherent flexibility cavalry is often the ideal economy-of-force option in operations. Emitting a low signature and with limited manpower, a cavalry force can, if used with skill, have a disproportionate influence throughout an area of operations. Cavalry have protection, and can quickly disperse or concentrate, can apply precision direct-fire, and maximise the effects of offensive support and joint assets without large numbers of personnel. Such operational features are invaluable in conditions where resource limitations and tight mission constraints are often found.

Cavalry should be augmented, or cross-attached, to other units in exactly the same manner as any other manoeuvre arm. Like other manoeuvre elements, cavalry units should also be fully integrated into the combined arms team in order to execute close combat effectively. For example, in Exercise Crocodile 2003, the cavalry battle group, Battle Group Eagle, consisted of two ASLAV cavalry squadrons operating with a tank squadron, an aviation reconnaissance squadron, an M113 armoured personnel carrier squadron, air defence and combat engineer elements and a US Marine Corps light infantry company. An indicative ASLAV cavalry combat team is outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustrative ASLAV Cavalry Combat Team by Combined Arms ‘Brick’ Structure

Note: The Cavalry troop is the basic ‘brick’ for cross-attachment to other manoeuvre battle group or combat teams.

Cavalry, Special Forces and Light Forces

Cavalry units are easily integrated with light infantry. Although such integration does not regularly occur on exercises, it has been standard procedure during the operational employment of Australian light armour. In recent times, standard operational employment has seen cavalry groupings assigned to the command responsibility of either special forces or light infantry. While this integration of armour and infantry has generally proven successful, it is necessary to consider assigning light infantry to the command of armoured cavalry both on exercise and during operations. In terms of tactical lift and mobility, a cavalry squadron can almost carry an infantry company. Such a mixture of light armour and ground troops highlights the advantage of exploiting the versatility of cavalry organisation.

Furthermore, ASLAV cavalry are ideal in bridging the gap between conventional and unconventional operations. Cavalry can lift, insert and support troops as well as conduct a wide variety of operations in concert with special force elements. For example, between 1999 and 2001, Australian Special Air Service patrols operated with ASLAVs in East Timor and from 2001–02 deployed with US Marine Corps light-armoured vehicles in southern Afghanistan. In certain circumstances, ASLAVs could be used for domestic counter-terrorism operations. A cavalry battle group could, for instance, employ special forces to assist in the conduct of security or offensive missions across an extended area of operations.

Between 1986 and 1993, a battle grouping methodology that was developed at the US Army National Training Center resulted in at least twenty light- and heavy-force rotations through the Center, all of which proved flexible and adaptable. It is worth noting that not a single cavalry combat team is scheduled to move through the Australian Combat Training Centre. The latter conducts eight annual live combat team rotations. However, only one of these rotations involves heavy forces and none, in fact, are composed of cavalry or are integrated between cavalry and infantry.

Cavalry's Tactical Ethos

Understanding the mentality of the cavalry is the key to grasping how mounted formations seek to fight. From Hannibal through Prince Rupert of the Rhine and Murat to the Cossacks under Budjenny, cavalry commanders have always possessed dash and flamboyance in their approach to warfighting. Such an ethos remains relevant in 21st-century military operations and was summed up in September 1933 by George S. Patton Jr when he wrote: ‘wars may be fought with weapons, but they are won by men’. The cavalry style was famously commented on by General Allenby in 1919 when he explained that the Australian Light Horse had ‘the gift of adaptability’ based on ‘a restless spirit of mind’ and the capacity to fight ‘mounted or on foot ... on every variety of ground’.4 Cavalry have always embodied the doctrine of mission command since in the cavalryman’s philosophy there has never been any other effective method by which mobile, fast-moving mounted troops can operate successfully.

In the Australian cavalry tradition, current doctrine and training emphasises mission focus, adaptability and what might be called a bias for action. When this ethos is combined with the modern networked nature of the ASLAV-3 vehicle, the cavalry organisation generated represents arguably the best opportunity for achieving the Australian Army’s self-synchronising aspirations. Networked cavalry will be of great value in both the Army’s manoeuvre operations in a littoral environment (MOLE) concept 5 and in the devolved situational awareness that is outlined in the Army’s Future Land Operational Concept (FLOC) entitled ‘Complex Warfighting’. 6 Mounted forces are predisposed towards the use of technology in military action, and the interface between human and machine is a key ingredient in achieving effective self-synchronisation.

Cavalry in Military History: Myth and Reality

Despite the advantages outlined above, in the Australian military profession, cavalry often remains a mystery—indeed almost a ‘black art’ to those outside mounted soldiering. Failure to understand the use of cavalry is often due to a number of misconceptions and myths that inhibit a wider professional undertstanding of mounted forces. It is essential to debunk two key myths about cavalry if the Army is to make any real progress in developing its light-armoured capabilities.

The Myth of Reconnaissance

The first misconception about the role of modern cavalry is what might be called the myth of reconnaissance. Most Australian Army studies, from Army 21 in the first half of the 1990s through the Restructure the Army Trial in the late 1990s, have identified a role for cavalry in reconnaissance. As a result, there is a strong tendency among many Army officers to view the cavalry as little more than a specialised reconnaissance force.

During the 1990s, this perception was so powerful that it led to the word ‘reconnaissance’ being briefly added to the 2nd Cavalry Regiment’s name. Indeed, current references to ASLAV cavalry in various Army capability documents still tend to refer to mounted forces as ‘armoured reconnaissance’ or ‘reconnaissance’ rather than as cavalry. Such an approach is the result of a military educational system that has given little appreciation to cavalry as a genuine general-purpose force. The belief that cavalry should be confined to reconnaissance represents a mentality that views mounted armour merely as a screen that operates ahead of the real combat arms. Cavalry is perceived to be an older, one-dimensional force—useful only for scouting forward but too light and vulnerable for 21st-century conflict, where heavier forces are required. Yet reconnaissance is simply a task and cannot justify a proper unit role. Moreover, even a brief reference to the historical record illustrates that adherence to a philosophy of ‘cavalry equals reconnaissance’ is untenable.

In the 1930s, when the US Army mechanised its cavalry, it did not immediately transfer the traditional all-purpose combat role of horse cavalry across to the new motorised organisations. Instead, the US Army decided that its new mechanised cavalry would focus on reconnaissance tasks. In 1934 US Army cavalry doctrine noted, ‘[cavalry] is the agent par excellence for ground reconnaissance’. 7 This decision did not survive the test of combat in World War II. The latter conflict revealed that reconnaissance tasks accounted for only 3 per cent of cavalry activity. General defence and security missions accounted for 58 per cent of cavalry operations, with offensive tasks and special operations taking up a further 10 per cent and 29 per cent respectively. These realities led the US Army to the conclusion that cavalry must be ‘specifically designed as a robust organisation capable of independent combat’. 8 As a result, the mechanised US Army cavalry returned to the multipurpose combat role of its horse-borne forebears.

The US Army subsequently employed armoured cavalry extensively and effectively in Vietnam. 9 For example, during the Tet Offensive in January 1968, the United States employed five armoured cavalry battalions against the Viet Cong. One officer wrote that their use was ‘an exercise in mobility that is the heart of cavalry operations’. As five cavalry squadrons (battalions) converged on the fighting in the Saigon area, ‘the outcome [of the fighting] was never in doubt. We knew that our enemy could never match our mobility, flexibility, and firepower’. 10

Since Vietnam, US cavalry have been viewed as a versatile ground–air combat organisation. The US Marine Corps Light-armoured Regiment using the LAV-25 formed the tip of the spear for operations in Panama, Somalia and Haiti, as well as in both the 1991 and 2003 Gulf Wars. During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, Task Force Tripoli, consisting of three LAR battalions with additional light infantry, executed a 150-mile attack beyond Baghdad to Tikrit and Bayji. Throughout the campaign, Marine light armour conducted a full range of traditional cavalry tasks, including close combat when operating as part of a combined arms team. 11

The Americans have not been alone in discovering the multipurpose value of modern cavalry. Both the British and the Russians have used cavalry beyond the reconnaissance role. In 1982, the British Army deployed light-armoured cavalry to the Falkland Islands, where it was used with decisive effect. For example, at Wireless Ridge, parachute troops conducted an assault supported by direct fire from Scimitar and Scorpion armoured vehicles. Unlike the infantry-only assault at Goose Green that proved costly in lives, the combined arms attack at Wireless Ridge was carried out with minimal casualties. One analyst of the Falklands War concluded, ‘even against a relatively untrained force, light infantry need the direct support of armoured forces as part of the combined arms team to effectively accomplish their missions with minimal casualties’. 12 For their part, the Soviets in Afghanistan discovered in the 1980s the value of light armour in prosecuting operations against the mujahideen. Soviet ground forces applied the bronegruppa concept involving the all-arms employment of BMP, BMD and BTR light-armoured vehicles with infantry, special forces, helicopters, tanks and artillery. 13

Moving from the general to the particular, Australia’s historical experience of cavalry operations is also instructive in debunking the reconnaissance myth. At the beginning of World War II each division of the 2nd AIF included a divisional reconnaissance regiment. Yet in 1939 the Army changed the name from ‘reconnaissance’ to ‘cavalry’ regiments and cavalry unit was equipped with forty-four light tanks, forty-four machine gun carriers and 450 men.

The divisional cavalry regiments of the 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions were deployed and saw service in a broad range of tasks, ranging from attack and raiding to screening, security and defensive missions. Australian cavalry fought in both mounted and dismounted operations in North Africa and the Middle East. On their return to the South-West Pacific theatre, cavalry units also fought throughout the islands as dismounted commandos. Only the 8th Division decided not to deploy its cavalry regiment since it was deemed ‘not to be required’ in the jungles of Malaya. 14

Like the Americans, the Australians discovered the value of light armour and of tanks in Vietnam. In 1970, towards the end of the Vietnam War, an Australian Army Battle Analysis Team concluded that the ‘collective armour experience (US and Australian) in RVN [Republic of Vietnam] has proven the armoured cavalry organisation to be the most suitable, versatile and successful form of armour for counter-revolutionary warfare’. 15 The report went on to note that Australian M113 squadrons had conducted a ‘preponderance of cavalry tasks in RVN’. 16 It recommended a number of organisational changes, including wheeled vehicles and long-range, direct-fire weapons, many of which are reflected in the current structure and doctrine of today’s cavalry.

Cavalry continue to have a relevant combat role. In 1999, Australian ASLAV cavalry supported the Australian Special Air Service Regiment in operations along the border between East and West Timor during Operation Stabilise. In southern Afghanistan in December 2001, Australian Special Air Service elements conducted initial operations in concert with US Marine Corps light-armoured, mounted forces.

The above American, British, Russian and Australian examples from the historical record suggest that it is incorrect to view cavalry as merely a specialised reconnaissance force. Yet old myths die hard, and developing doctrine in the Australian Army continues to insist that ‘cavalry conducts reconnaissance ... Cavalry enables supported commanders to manoeuvre their force with enhanced security and to preserve combat power until it can be employed decisively’. 17 The very reason that cavalry has traditionally assumed the reconnaissance task is not because of its specialisation, but rather because of its versatile and multipurpose combat role. Cavalry forces can be stealthy or not; they can fight for information and intelligence; they can operate in mounted or dismounted roles, or in both simultaneously.

Cavalry units are inherently adaptable, and it is this capacity that makes them ideal for undertaking uncertain and unpredictable reconnaissance missions. In short, cavalry elements effectively conduct reconnaissance tasks because of their versatility, agility and adaptability. Cavalry, however, have never conducted reconnaissance tasks as a raison d’être. Historically, it has been because cavalry units are general-purpose rather than specialised units that they have been able to assume responsibility for a range of difficult reconnaissance tasks.

The Myth of Vulnerability

The second myth about light-armoured cavalry concerns their vulnerability to hostile fires. In the case of the ASLAV, this argument is predicated on a belief that the vehicle’s light armour is too thin to provide protection against missiles and rocket-propelled grenades. Those critics that view the ASLAV as too vulnerable often incorrectly view protection as merely a function of the thickness of armour plating. Current ASLAV armour is, in fact, thicker than the DPCU shirt, as well as that of the entire ‘B’ vehicle fleet and every special forces’ wheeled vehicle. Indeed, the ASLAV’s skin is comparable in pure thickness to the skins of the M113 and Bushmaster vehicles. In other words, it is not only the ASLAV that is vulnerable, but also the M113 and the Bushmaster vehicles.

The Army needs to realise that the protection of the ASLAV is not simply a question of the thickness of armour. Protection must be viewed in holistic terms. It embraces questions of firepower, mobility, optics, situational awareness, connectivity and suitable tactics, all of which come into play during operations. From the perspective of capabilities and versatility, ASLAV cavalry units are arguably the most protected manoeuvre element in the current Australian Army.

Furthermore, it is important to understand that a narrow definition of protection by armour thickness is inadequate from the combined arms perspective. The combination of armour, infantry, artillery and engineers is designed to ensure that in combat the whole of the military machine is greater than the sum of its parts. The essence of a combined arms philosophy is one of coordination in order to minimise each combat arm’s vulnerabilities while maximising their respective strengths. Under a combined arms combat system, the ASLAV-3 cavalry regiment can be regarded as a well-protected and highly lethal force.

It is worth noting that, while the US Marines in their march north towards Baghdad during the Second Gulf War in early 2003 suffered multiple hits from enemy weapons systems on their light-armoured vehicles, no single vehicle was comprehensively destroyed by enemy action. Cavalry, then, represents a multi-role combat organisation and, when integrated into the combined arms team, offers reduced risk in action. The difficulty in the Australian Army has been that mounted armour has often been poorly understood and the Army has made various attempts to limit the capability to ‘specialist roles’ such as reconnaissance.

In fact, as indicated earlier, light-armoured forces have been used extensively by the Australian Army in recent operations. ASLAV cavalry were employed from 1999 to 2002 in East Timor and supported Australian infantry operating along the East Timor border in search and reconnaissance missions, ready reaction, offensive patrolling, tactical lift, and security tasks. ASLAV cavalry have also been on short-notice standby to support a number of security and peace support operations in the South-West Pacific and have been deployed as part of the Australian security effort in Iraq.

In what can be regarded as a general trend, most leading Western armies from New Zealand to the United States are today investing time and resources into developing light-armoured cavalry as part of a response to the challenges posed by modern operations. The New Zealand Army has introduced the LAV-3 vehicle into its force structure in order to realise its motorised infantry concepts. In addition, over the past few years, the US Marine Corps has focused on expanding its light-armoured capabilities. In 1997 the Marine Corps’ light-armoured regiments were combined into a Special Purpose Marine Ground Task Force to conduct deep operations as a ‘light armour operational manoeuvre element’. 18 Meanwhile, the US Army’s Stryker Brigade Combat Teams employ light-armoured vehicles, and the first Stryker team is currently deployed on operations in Iraq.

Conclusion

In the Australian Army, the value of light-armoured cavalry is underestimated by a poor professional understanding of the use of cavalry in general and the use of light-armoured cavalry in particular. The reality is that light-armoured cavalry fit uneasily into an Army tactical culture that is overwhelmingly infantry in orientation and character. Yet the use of cavalry must be better understood lest we risk failing to exploit our light-armoured capability to its full potential.

Used in a combined arms framework, ASLAV cavalry provide an adaptable and multipurpose combat element. The intelligent use of ASLAV forces is entirely consistent with the parameters of the HNA initiative, which seeks to produce a versatile combat organisation capable of executing a variety of tasks across the spectrum of conflict. ASLAV cavalry should not be confined to a narrow conventional reconnaissance role. Nor should such force elements be regarded as a mere contribution to more traditional manoeuvre units such as enhancing an armoured personnel carrier capacity or providing a mobile fire-support package for dismounted units. The Army needs to grasp that cavalry can readily form the basis of combined arms combat teams and battle groups for a wide variety of missions.

Future progress towards a more comprehensive understanding and employment of cavalry in the Australian Army will depend on education, training and professional mastery. Combined arms warfare must be developed in a way that dispels myth and preconception about the value of light-armoured vehicles. Failure to view mounted armour as a combined arms resource may be reassuring to those that cling to the status quo, but such an outlook is likely to be retrograde in the long term and will lead to missed opportunities in modernising the land force. Lack of critical analysis of the Army’s future combat needs will lead to an inability to adapt to changing circumstances, and soldiers should remember that battle is unforgiving of error.

The truth is clear: in light-armoured cavalry, the land force already has part of the answer to the challenges of the 21st century outlined in the Chief of Army’s HNA initiative. Soldiers need to understand, accept and exploit cavalry capability for the good of the future Army.

Endnotes

1 USMC Lessons Learned Operation Iraqi Freedom, G3 Topic: Light-armoured Regiment and Battalion Organic to the Marine Division, <www.globalsecurity.org>.

2 See Australian Army, Future Land Warfare Branch, ‘Complex Warfighting’, Future Land Operational Concept (FLOC), draft as at 7 April 2004, para. 77.

3 Australian Army, Land Warfare Procedures—Combat Arms LWP-CA (MTD CBT) 3-3-2, Cavalry Operations (Developing Doctrine), 30 November 2001; and Australian Army, Land Warfare Doctrine, Cavalry Troop Leaders Handbook (Developing Doctrine), LWD 3-3-2-1 (Draft). Developing doctrine will be reproduced in 2004 as The Cavalry Regiment along with a Cavalry Troop Leaders Handbook.

4 H. S. Gullet, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–18, vol. VII, Sinai and Palestine, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1940, p. 791.

5 Australian Army, Army Development Concept for Decisive Actions, Future Land Warfare Branch, Army Headquarters, 10 April 2003, p. 4, defines self-synchronisation as ‘the effective, self-initiated interaction between two or more military elements to achieve the superior commander’s intent’ without reference to a traditional command-and-control hierarchy or additional direction.

6 ‘Complex Warfighting’, para. 58h.

7 US Army, Tactics and Techniques of Cavalry: A Text and Reference Book of Cavalry Training, The Military Service Publishing Company, Washington, DC, 1934, p. 10.

8 L. Dimarco, ‘Mechanised Cavalry Doctrine in WWII’, <http://www.geocities.com/dimarcola/doctrine_chapter_1.htm>, Introduction, p. 3 of 3; Doctrine, ch. 4, p. 3 of 23.

9 US Army cavalry organisations included M113 ACAV, tanks, dismounts and air cavalry.

10 M. D. Mahler, Ringed in Steel: Armoured Cavalry, Vietnam 1967–68, Presidio Press, Novato, CA, 1998, p. 101.

11 See Joe Day, ‘To Baghdad and Beyond: A Personal Account of the War in Iraq’, Ironsides: The Journal of the Royal Australian Armoured Corps, 2003, p. 9.

12 Captain D. T. Head, ‘The 2nd Parachute Battalion’s War in the Falklands: Light Armor Made the Difference in South Atlantic Deployment’, Armor, September–October 1999, p. 9.

13 The Frunze Academy, ‘The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Tactics and Tactical Lessons Learned During Their War in Afghanistan, Part 1, 2, 3’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, September 1994, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 599.

14 P. Handel, Dust, Sand and Jungle: A History of Australian Armour 1927–1948, Australian Military History Publication, Sydney, 2003, p. 15.

15 Australian Army, Armour in Counter-Revolutionary Warfare, Army Headquarters Battle Analysis Team, Canberra, March 1970, p. 112.

16 Ibid., pp. 96; 107.

17 ‘Cavalry Operations’ (Developing Doctrine), p. 1-1.

18 T. B. Sward and T. L. Tyrrell Jr, ‘Marine Light Armour and Deep Maneuver’, Marine Corps Gazette, December 1997, p. 16.