- Home

- Library

- Volume 21 Number 1

- Optimising the Cavalry for Littoral Manoeuvre

Optimising the Cavalry for Littoral Manoeuvre

At the start of World War II, the Australian Army formed divisional cavalry regiments to support the 6th, 7th and 9th divisions. Equipped with a diverse array of vehicles, these regiments successfully supported their parent divisions during operations against the Axis in the Middle East in 1940–1942. Following the recall of the Australian divisions to fight against Japan, it was determined that the divisional cavalry regiments were unsuited to the style of fighting required in the Pacific islands. As a result, they were reformed as cavalry commando regiments optimised for asymmetrical operations. These regiments successfully supported the conduct of littoral manoeuvre throughout the archipelago in Australia’s primary area of military interest until the end of the war.

As Mark Twain is reported to have said, ‘history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes’.[1] Today, the Australian Army’s cavalry finds itself in a similar position to that of 80 years ago. Following many years of successful service in the Middle East, the cavalry must now optimise for the next fight in the Pacific. The Defence Strategic Review 2023 (DSR) directs the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to evolve into an integrated force[2] able to manoeuvre in all domains to achieve the aims of national defence. To give effect to this strategy, the DSR tasks the Australian Army to transform and optimise for littoral manoeuvre operations by sea, land and air from Australia.[3] The National Defence Strategy 2024 (NDS) expands on this priority by directing the Army to ‘optimise... for littoral manoeuvre and control of strategic land positions’.[4] This capability is intended to enable the integrated force to achieve an asymmetrical advantage in support of the nation’s strategy of denial. The timeframe for this transformation is aggressive, with the enhanced force-in-being to be achieved by the end of 2025.

The aim of this article is to outline how the Australian Army’s cavalry can modernise and optimise to achieve an asymmetrical advantage in support of a national strategy of denial enabled by a focus on littoral manoeuvre.[5] The article will first describe the challenges for the cavalry due to the evolving operational context. It will then outline an optimised cavalry contribution to littoral manoeuvre. It will conclude by suggesting solutions and investment priorities to optimise the cavalry for the challenges of the future.

Endnotes

[1] While this is generally attributed to Mark Twain, there is no compelling evidence that he actually said it.

[2] Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 19.

[3] Ibid., p. 58.

[4] Australian Government, National Defence Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 38.

[5] This paper explores only the full-time cavalry in the 1st Australian Division. It is this cavalry force that will support littoral manoeuvre. There will, however, be themes of relevance to the part-time cavalry in the 2nd Australian Division, for their critical homeland defence mission.

To establish a baseline for how the cavalry can optimise to support the integrated force in littoral manoeuvre, it is useful to describe the current cavalry contribution to the combined arms team. The purpose of the combined arms team is to defeat the adversary. As part of the combined arms team, however, the cavalry rarely defeats the adversary directly. Instead, it typically enables something else (usually described as the supported force or main body) to defeat the adversary. The majority of the cavalry’s actions have the purpose of enabling the supported commander to achieve their mission.[6]

The cavalry does this by exploiting asymmetry to gain a relative advantage for the supported commander. Specifically, it fights for information about the adversary’s strengths and weaknesses, and where and when they will present. This allows the supported commander to apply their own strengths against adversary weaknesses, while avoiding adversary strengths. This is the heart of manoeuvre warfare. In parallel, the cavalry denies the adversary information about the supported force, degrades its cohesion, and pre-empts the employment of its critical capabilities. The adversary is thereby compelled to react to the cavalry’s actions rather than executing its own course of action, often expending its strength at the wrong place and time. These actions act as a force multiplier, and allow a supported force that is smaller and weaker than the adversary to achieve victory.

To achieve these effects, the cavalry conducts reconnaissance and security tasks. Reconnaissance tasks have a primarily offensive focus—to identify battlefield opportunities and enable the supported commander to exploit these opportunities. This is known as ‘reconnaissance pull’. Security tasks have a primarily protective focus—preventing the adversary from achieving surprise or from applying its strengths against the supported force. The cavalry employs both offensive and defensive techniques while conducting reconnaissance and security tasks. In particular, it employs the techniques of raid and reconnaissance in force to reduce the cohesion of the adversary and to pre-empt the employment of its critical capabilities. The cavalry is also a primary capability available to the supported commander to achieve deception, with the cavalry able to conceal or simulate the main effort in support of the deception objective.

Currently, the majority of the full-time cavalry is equipped with the Australian Light Armoured Vehicle (ASLAV). This proven vehicle is in the process of being replaced by the Boxer Cavalry Reconnaissance Vehicle (Boxer CRV).[7] This is an exceptionally capable vehicle; however, it is much larger and heavier than the ASLAV. Following the DSR, the full-time cavalry capability is being concentrated in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment and the 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment.[8] Cavalry troops will re-adopt a six-vehicle structure, providing greater capability and endurance at lower levels of command.

What Has Changed?

The DSR tasks the Army to optimise for littoral manoeuvre. However, as the only arm of government able to conduct sustained close combat, the Army is also expected to continue to provide ‘close combat capabilities … able to meet the most demanding land challenges in our region’.[9] In effect, the Army must be able to fight as part of a coalition, as well as to lead regional operations, including stability operations. The cavalry, therefore, must remain capable of the full suite of cavalry tasks in support of land manoeuvre, in addition to developing new capabilities and competency in littoral manoeuvre.

While there is continuity in the Army’s taskings, the new operational context of littoral manoeuvre introduces new challenges, particularly for the cavalry. These can be summarised as follows:

The nature of the supported force. The foremost difference is that the nature of the supported force has evolved. The supported force is no longer likely to be a concentrated brigade or division seeking decision in close combat. Instead, it is more likely to be a dispersed force package operating to secure strategic land positions in Australia’s primary area of military interest.[10] This force package is likely to include long-range strike and ground-based air and missile defence capabilities, able to project combat power into the air and maritime domains to achieve sea and air denial. This change reflects a doctrinal shift away from the traditional paradigm of ‘fire to manoeuvre’ to one of ‘manoeuvre to fire’.[11] Since the cavalry’s purpose is to enable the supported commander to achieve their mission, it is this change that most affects the nature of the cavalry contribution.

The littoral battlespace. The next (obvious) difference is the challenge posed by the battlespace itself. Australia’s primary area of military interest is archipelagic in character, which is a confluence of the sea, land and air domains. Littoral operations require a force with cross-domain mobility.[12] The challenge for the cavalry is to optimise for manoeuvre in a littoral battlespace. This includes the ability to deploy by air and sea, manoeuvre across and between landmasses, manoeuvre using rivers, manoeuvre in complex physical terrain (such as jungles and cities), and manoeuvre in areas with poor infrastructure (such as ports, roads and bridges).

Distributed operations. A strategy of denial envisages multiple tailored force packages independently deploying over long ranges and operating in a dispersed way over large distances.[13] The cavalry, therefore, must be able to support multiple small elements operating independently, but to a common purpose, over large distances in an archipelagic environment. In this context, the challenge for the cavalry is to manoeuvre, sense and strike on both land and sea at longer ranges than has previously been required.

Cross-domain effects. Littoral manoeuvre requires land domain forces to project combat power into other domains, particularly the air and maritime domains.[14] This is necessary to achieve an asymmetric advantage and support the strategy of denial. The challenge for the cavalry is to be able to be able to achieve the combat functions of ‘know, shield, shape and strike’ in more than just the land domain.

Compression of operational and tactical levels of war. In the land domain, there has traditionally been a linear relationship between the level of command and the relative battlefield effects. For example, divisions and below have tactical effects, while corps-level formations and up have operational effects. In littoral manoeuvre, this distinction is generally compressed due to the non-linear and multi-domain nature of the operational environment. In this environment, lower echelons, such as combat teams and battlegroups, will frequently give effect to operational-level objectives. The challenge for the cavalry is to enable the achievement of these operational effects by lower tactical echelons.

The Cavalry Contribution to Littoral Manoeuvre

The core purpose of the cavalry is still relevant, and indeed necessary, in the context of littoral manoeuvre operations. However, the role of the cavalry needs to evolve. To borrow a phrase from Clausewitz, the nature of the cavalry is enduring, but its character is changing.[15] The need to change stems from Australia’s evolving national strategy, outlined above, which necessarily modifies how the cavalry achieves its purpose. Specifically, the unification of the five domains of maritime, land, air, space and cyber, which is a characteristic of the integrated force, requires the Army to project combat power beyond the land domain in ways it has not previously had to achieve. To better understand how the cavalry needs to respond to this new operational context, it is first necessary to define the scope of the cavalry contribution to the other domains. In this regard, defining the scope of the cavalry’s area of operations is a useful starting point.

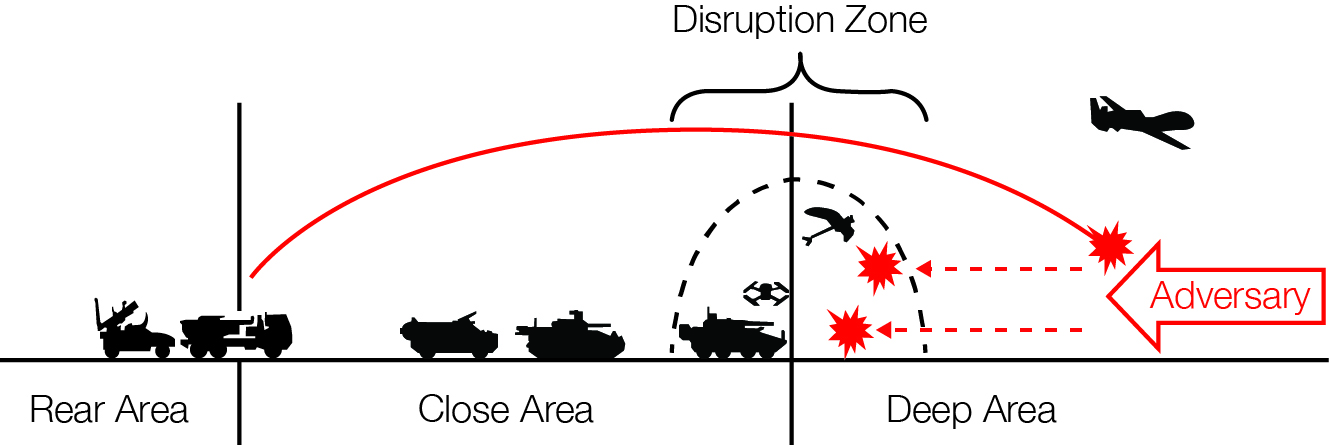

Australian doctrine outlines the use of a deep, close and rear operational framework to enable coordination between levels of command and between force elements.[16] In an article published in the US Armor magazine, Major Amos C Fox proposed an evolved operational framework to describe the cavalry contribution to modern multi-domain operations.[17] This framework includes an additional ‘security zone’—between the deep and the close areas. This zone exists in four dimensions (including time) and across the physical domains (land, maritime and air). In addition, this zone is conceptualised as forming a physical transition point between the tactical fight and the operational fight. In this framework, the security zone is the cavalry’s area of operations. For the purposes of this article, this zone is described as the ‘disruption zone’ to better express its purpose and to avoid confusion with security operations.

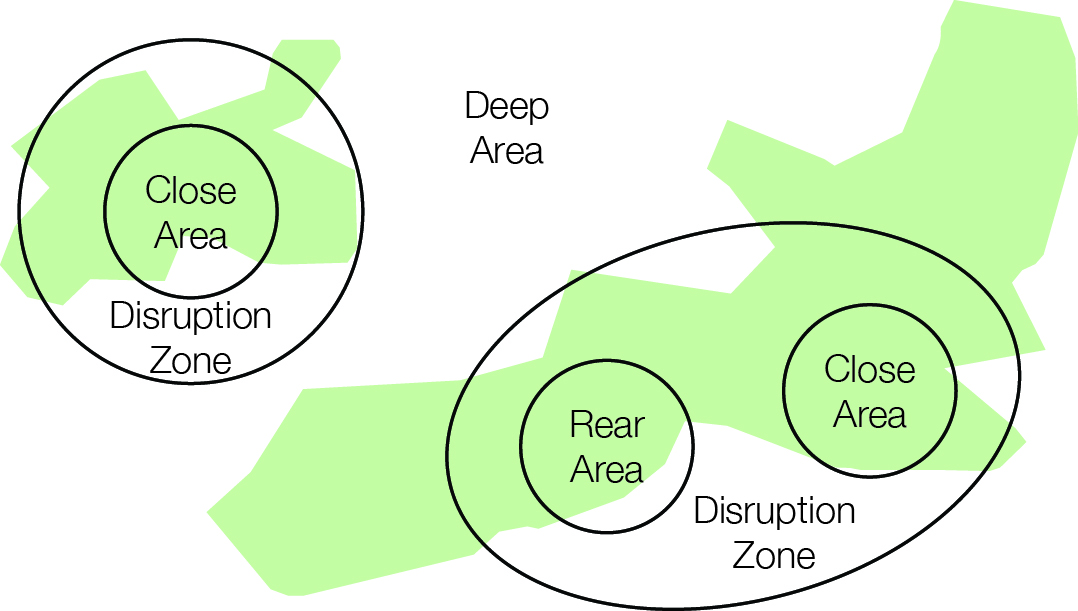

This framework provides a doctrinal basis for defining the cavalry’s contribution to the integrated force and, in particular, to littoral manoeuvre. The cavalry manages the transition between the close area and the deep area, as well as the transition between the operational-level and the tactical-level fights. It establishes a disruption zone to enable friendly critical capabilities that can influence the adversary in the deep area. At the same time, the cavalry disrupts the adversary’s forces as they transition into the disruption zone in an effort to defeat friendly critical capabilities. The dispersed and non-linear nature of littoral operations increases the scale and number of these transitions. The disruption zone, and therefore the cavalry contribution, is thus more important in littoral operations than in continental operations.

Figure 2. Non-linear nature of littoral operations

Importantly, this disruption zone is not only protective in nature, within which the cavalry conducts screen or guard tasks. Rather, the cavalry conducts both reconnaissance and security operations in the disruption zone, in support of both offensive and defensive actions by the supported force. For example, the cavalry might first conduct reconnaissance to set conditions for the arrival of the main body, followed by a raid to neutralise adversary critical capabilities, before establishing a guard to protect friendly critical capabilities—all within the disruption zone.

The size of the disruption zone limits the scope of operations for the cavalry in the different domains. Affecting both land and maritime domains, the depth of the disruption zone is likely to be in the order of tens of kilometres. To achieve its purpose, the cavalry must be able to sense and strike surface targets (on land and sea) out to this range. In the air domain, the altitude of the disruption zone is likely to be in the order of hundreds of metres. While the cavalry must be able to sense and shield from low-flying aircraft such as helicopters, small uncrewed aerial systems (sUAS) and loitering munitions, it does not need to provide protection against higher-flying aircraft or missiles. The ‘time’ dimension is likely to be in the order of 24–72 hours. This means the cavalry must be able to support the operations of the supported force up to three days ahead of time, as well as being able to gain information on the adversary up to three days before it can influence the supported force. In effect, the cavalry operates one operational phase ahead of the main body. The cavalry contribution to the cyber and space domains is limited to self-protection and deception; the adversary does not manoeuvre through the disruption zone in these domains.

Historical Example

The Battle of Milne Bay provides an historical example of the value of a disruption zone in littoral operations. In 1942 Australian forces, supported by the US Army, constructed an airstrip at Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea to operate fighter and attack aircraft. The purpose of the airstrip was to enable the projection of combat power in the maritime and air domains, to achieve local air and sea control. This level of control would protect Port Moresby from Japanese air and naval forces, protect the sea lines of communication to Australia, and threaten the Japanese forward support base at Rabaul. The airstrip at Milne Bay was protected by a security force consisting of the 7th and 18th Brigades, eventually under the command of Major General Cyril Clowes.

The presence of the Allied airstrip was an unacceptable threat to the Japanese military’s campaign plan in the South-West Pacific. The Japanese military was unable to defeat the Allied force at Milne Bay with air or naval forces alone and was instead forced to commit land forces. Japanese troops conducted an unopposed landing with a brigade-sized force under cover of darkness 15 kilometres from the airstrip. This force then conducted an overland march with the intent of defeating the Australian security force and capturing the airfield for its own use.

General Clowes’s ‘Milne Force’ significantly outnumbered the Japanese contingent. However, Milne Force lacked the capabilities necessary to establish an effective disruption zone and was unable to learn the strength and location of the advancing main body. As a result, the general was unable to mass his strength against the smaller Japanese force, and instead spread his forces wide to avoid envelopment and surprise. Japanese troops were thus able to approach to within a couple of kilometres of the airstrip, close enough that the P-40 Kittyhawks of 75 and 76 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force were forced to withdraw to Port Moresby.[18] It was only through the courage and skill of the 7th and 18th Brigades in a desperate night fight that the Japanese attack was eventually defeated.[19]

To gauge the potential utility of the disruption zone concept, it is instructive to consider a repeat of the Battle of Milne Bay, but this time with Milne Force effectively supported by a cavalry force operating within the zone. To begin, the mere presence of this disruption zone would influence the adversary’s decision-making. Specifically, the adversary would be forced to allocate more resources to the attack to have an acceptable chance of success. The prospect of having to commit additional combat power may deter the adversary from attacking at all, or at least prevent it from redirecting critical capabilities elsewhere to a battle more threatening to Australia’s national interests. In the event that the adversary elected to attack, it would be forced to commit to a more cautious landing outside the disruption zone, with a slower approach that would allow more time for counter-offensive measures by the defenders. Further, the adversary would be compelled to commit its critical capabilities in the disruption zone, rather than preserve them for use in the close or rear areas. Importantly, the adversary would not be able to gain sufficient information on the defenders to cue long-range fires of its own. Instead, the cavalry would learn the adversary’s strengths and weakness and thereby enable the supported commander to mass the close-combat forces against the adversary at the time and place of maximum relative advantage. Indeed, the commander would need fewer close-combat forces to defend the airfield in the first place. The forces not needed could be apportioned elsewhere, which would raise further operational dilemmas for the adversary.

Here we see the enduring role of the cavalry. It exploits asymmetry to gain a relative advantage for the supported commander. It manages the transition between the close area and the deep area, and between the operational fight and the tactical fight. It gains information on the adversary to prevent surprise, gain time for effective decision-making and enable the supported commander to mass their strengths against the adversary’s weaknesses. It influences adversary decision-making and pre-empts the employment of the adversary’s critical capabilities. It compels the adversary to expend strength at the wrong place and time. In short, it enables the supported force, and by extension the nation, to achieve victory at lowest cost and least risk.

This example illustrates the value proposition of the cavalry in support of littoral manoeuvre. Without an effective cavalry force able to establish a robust disruption zone, littoral manoeuvre force packages of the future may find themselves in the position of General Clowes’s Milne Force—that is, unaware of adversary strengths and locations, and unable to influence the fight beyond the range of direct-fire weapons in the close area. This may result in the situation experienced by Milne Force on the night of 28 August 1942—unable to protect long-range strike and air and missile defence capabilities, risking the success of Australia’s operational plans.

Endnotes

[6] Joshua Higgins provides an excellent description of the employment of cavalry, which expands on some of the themes explored here. Joshua E Higgins, ‘Achtung—Boxer! How to Employ Cavalry in the Mid-Twenty-First Century’, The Cove, 21 April 2020, at: https://cove.army.gov.au/article/achtung-boxer-how-employ-cavalry-mid-twenty-first-century.

[7] ‘Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle’, Department of Defence (website), February 2024, at: https://www.defence.gov.au/defence-activities/projects/combat-reconnaissance-vehicle.

[8] Defence Ministers, ‘Major Changes to Army Announced’, media release, 28 September 2023, at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2023-09-28/adapting-army-australias-strategic-circumstances.

[9] Defence Strategic Review, p. 58.

[10] Ibid., p. 40.

[11] The Ellis Group, ‘21st Century Maneuver’, Marine Corps Gazette, 1 February 2017, at: https://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/21st-century-maneuver/.

[12] Mathew Scott, ‘Tenets for Littoral Operations’, Australian Army Journal XIX, no. 2 (2023): 33.

[13] Albert Palazzo, Resetting the Australian Army, Australian Army Occasional Paper No. 16 (Australian Army Research Centre, 2023), p. 31.

[14] Scott, ‘Tenets for Littoral Operations’, p. 34.

[15] Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Palatino: Princeton University Press, 1976 [1832]), p. 33.

[16] Department of Defence, Australian Defence Force—Philosophical—3 Campaigns and Operations (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021), p. 104.

[17] Amos C Fox, ‘Looking Toward the Future: The U.S. Cavalry’s Role in Multi-Domain Battle’, US Army Magazine CXXVIII, no. 1 (2017): 25–32.

[18] This withdrawal was only temporary, on the night of 28 August 1942. The aircraft returned at dawn the next day and continued their decisive support of Milne Force.

[19] This section is drawn from Michael Veitch, Turning Point: The Battle for Milne Bay 1942—Japan’s First Land Defeat in World War II (Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2019).

Before discussing how the cavalry can be optimised for littoral manoeuvre, there is value in discussing relevant constraints. The DSR makes clear that the aim of capability acquisition is achieving a ‘minimum viable capability in the shortest possible time’.[20] The NDS adds that minimum viable capability is underpinned by minimum viable product, which ‘achieves or enables the lowest acceptable mission performance in the required time’.[21] Importantly, the NDS and accompanying Integrated Investment Plan specify resourcing constraints and affirm that available resources are to be allocated to the highest priorities. Put bluntly, the cavalry can expect no additional resources.

This significantly constrains capability options. For example, obtaining a new cavalry platform, or even making significant changes to the current or planned platforms, is not viable. Instead, capabilities with a high technological readiness level (preferably capabilities already in service or about to enter service) must be favoured over developmental solutions. Further, any new capabilities acquired by the ADF must work alongside and enable the cavalry platforms, but not be integrated into them.

While the resourcing constraints are significant, they do not preclude the cavalry adapting to the changing strategic circumstances. The divisional cavalry regiments in World War II provide an example of the sort of pragmatic approach to capability development that is required. During their campaigning in the Middle East, these regiments were equipped with whatever vehicles were available.[22] This included British light and cruiser tanks, British carriers and trucks, captured Italian tanks and captured French tanks. Despite their obvious limitations, these vehicles represented a minimum viable product, underpinning the minimum viable capability of the cavalry regiments to successfully support the operations of their parent divisions. Today’s cavalry must emulate this pragmatic approach to capability.

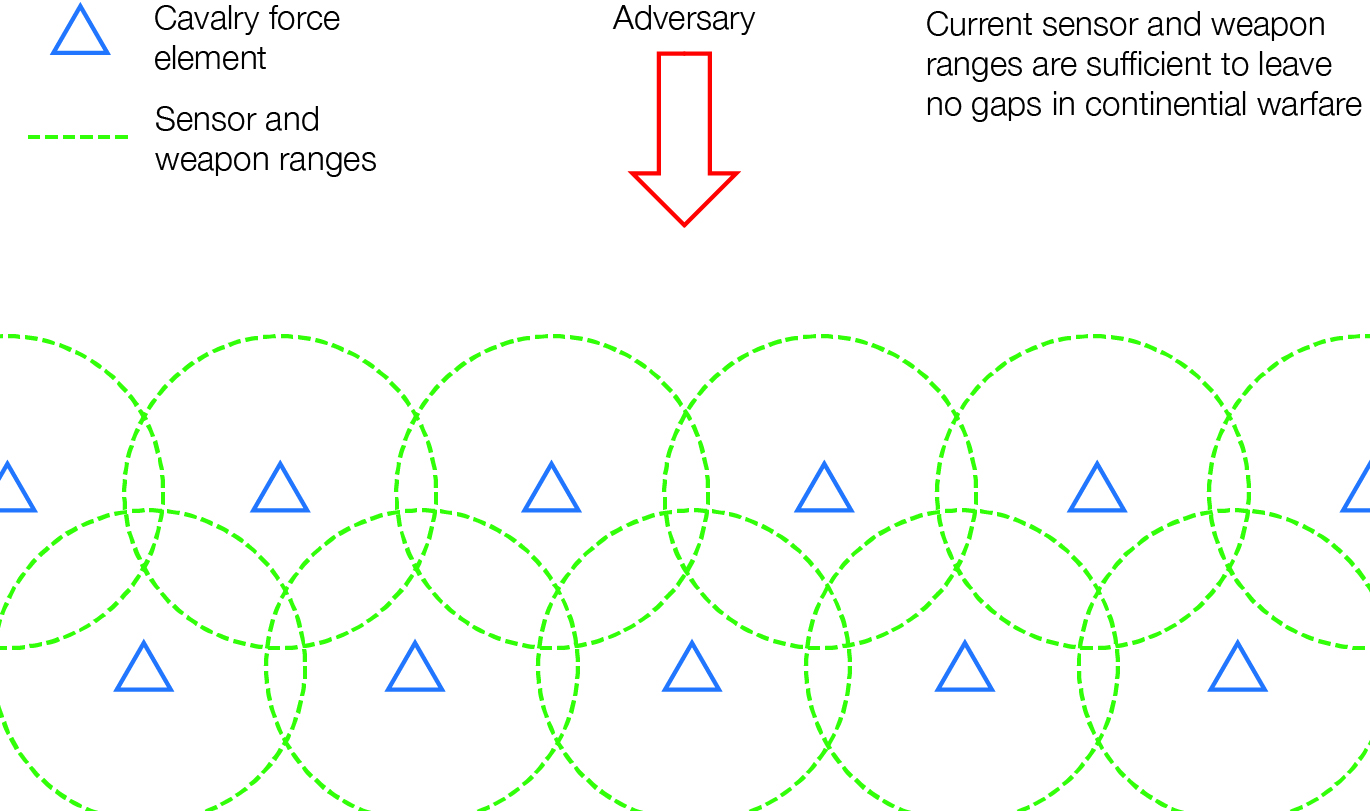

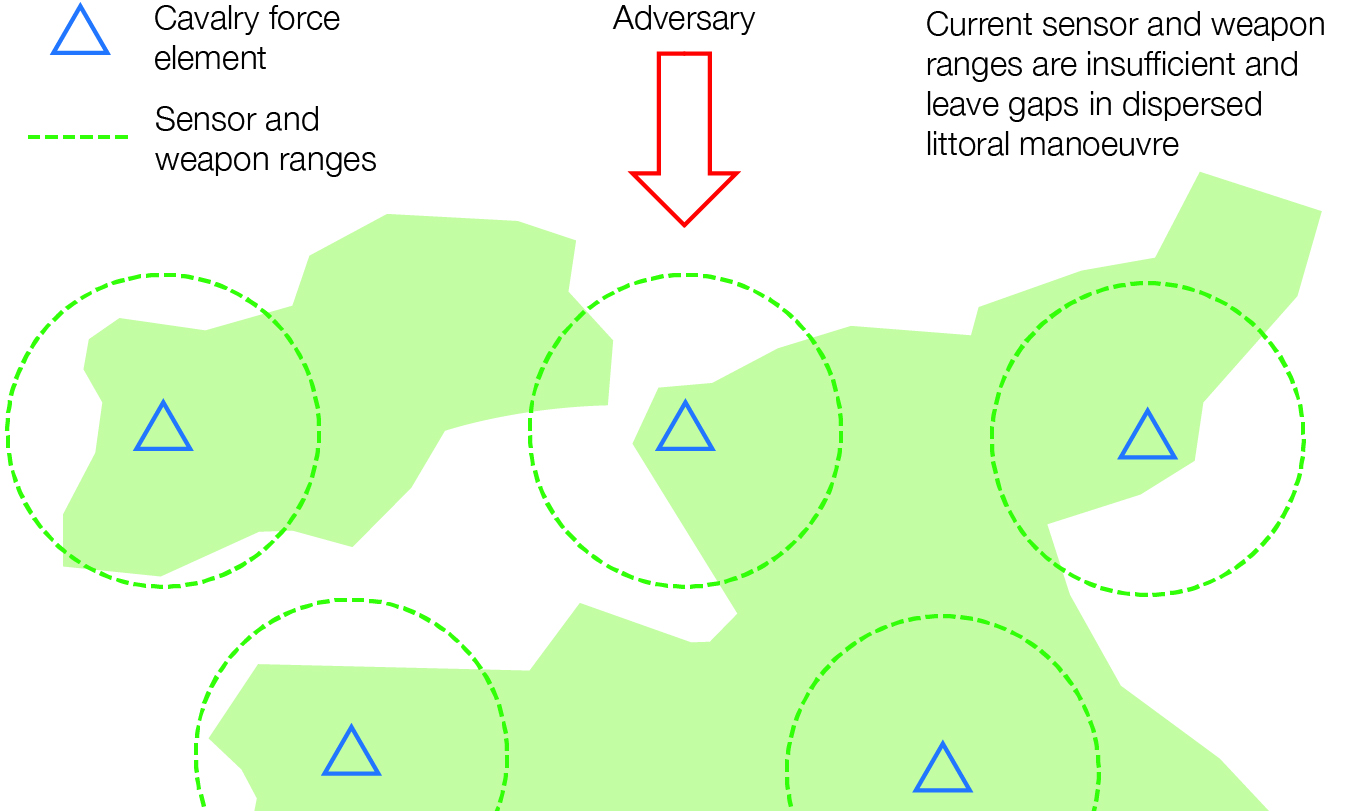

Distributed operations. Littoral operations will be conducted over large distances within an archipelago. In this operational environment, the challenge for the cavalry is to establish the large disruption zone required by littoral operations, without creating gaps that an adversary can exploit. Given the resource limitations on new major systems and workforce, and the associated constraints on deploying and sustaining them, it is simply not possible to deploy more cavalry to achieve a dense disruption zone. The only viable answer is to have the small number of existing cavalry force elements dispersed throughout the disruption zone and to exploit technology to cover the gaps. This approach requires the cavalry to be enabled with capabilities to sense and strike targets at longer ranges. The ability to sense at long ranges enables warning of adversary threats early enough to allow the main force to react and to provide targeting data for organic strike capabilities. By conducting limited strike at long range, the cavalry can neutralise the adversary’s critical capabilities as they transition the disruption zone and before they can threaten the supported force. Such actions raise the cost of aggression, thus influencing the adversary’s decision-making.[23]

Sense. A mixture of reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities is required to sense targets out to the full depth of the disruption zone. Surveillance capabilities allow observation of large areas for extended periods. Reconnaissance capabilities allow investigation of any detections and for contact to be maintained as adversaries transit through the disruption zone. The Boxer CRV is introducing a potent surveillance capability in the form of the VINGTAQS 2.[24] This mast-mounted multi-sensor system includes a ground surveillance radar, thermal imager and laser target designator, with a large detection range. This system is particularly effective at surveillance over the sea; however, it is less effective on land, due to the shadowing effects of terrain and vegetation. To prevent gaps in surveillance on land, long-endurance autonomous ground sensors can be employed.[25] A minimum viable capability would require enough systems for each troop to have a remote surveillance capability.

The requirement to conduct reconnaissance at long range, on both land and sea, can only be met by greater proliferation of sUAS. This is particularly the case when conducting reconnaissance over water or from one island to another, where cavalry platforms cannot go. Each level of command should have its own sUAS, enabling a layered reconnaissance network through the depth of the disruption zone. The longest-range systems, held at higher levels of command, can conduct reconnaissance of any detections at the forward edge of the disruption zone. As they transit through the disruption zone, these contacts can then be handed off to shorter-range systems. Given the greater dispersion of cavalry force elements in littoral operations, these capabilities must be held at lower levels of command than has previously been the case. For example, troops will require capabilities that were formerly held at squadron level, and squadrons will require capabilities that were previously held at regimental level. In practice, this change would see Army’s sUAS issued one level of command lower for the cavalry than for the close-combat force—that is, the longer-range RQ-20 Puma at squadron level; [26] the shorter-range Vector at troop level;[27] and small, cheap, and expendable sUAS at the lowest level.

To account for the high level of attrition expected in modern operations, tactically deployed low-level systems must be cheap and as numerous as possible. Experience from Ukraine has shown that the average lifespan of a typical ‘quad-copter’ sUAS is only three flights.[28] Therefore sUAS should be regarded not as weapon systems in themselves but as rounds of ammunition to be expended.[29] In this regard, sUAS can be manufactured for less than the cost of the advanced 30 mm ammunition being procured for the Boxer CRV, and should be issued and expended at the same scale.

Strike. The Boxer CRV will introduce the potent Spike LR2 Anti-Tank Guided Missile into the Australian Army inventory. This direct-fire weapon can engage a variety of targets at a range of more than 5 kilometres.[30] However, even this long-range direct-fire weapon does not enable Army to conduct limited strike through the depth of the disruption zone on both land and sea. This effect can only be achieved by an indirect-fire weapon system. As the cavalry will usually be operating outside the range of tube artillery, and with rocket artillery unlikely to be committed in support of the disruption zone, the cavalry must have its own indirect-fire weapon system to meet this requirement.

The cavalry must be able to provide targeting data for its own fires capability. This is because the other targeting capabilities within the integrated force will inevitably be employed in the deep area and not the disruption zone. The cavalry’s organic sUAS, cued by surveillance systems, is the best solution to provide the necessary targeting data. To form a cohesive targeting system, the range of the fires system should match the range of the sUAS available to the cavalry. Such a targeting system would enable the cavalry to independently detect, discriminate and neutralise adversary critical capabilities without committing soldiers to close combat. Delivering such a system would support the Chief of Army’s direction to avoid ‘trading blood on first contact’.[31]

The most suitable indirect fires system for the cavalry is likely to be a loitering munition. Loitering munitions have particular utility as they are generally cheap, precise, highly mobile, and able to effectively engage a wide variety of targets on land and sea; do not require integration into vehicles; can quickly be upgraded by replacement as technology progresses; and are soon to enter service with other elements of the integrated force.[32] The Switchblade series of loitering munitions, with a range in the tens of kilometres and an endurance in the tens of minutes, is an exemplar of the type of system required.[33] A minimum viable capability would likely be one mission system, including multiple munitions and a fire control station for each troop, per squadron. This would enable loitering munitions to be launched from depth, with control handed off to a forward troop, which would then control the terminal engagement. The additional systems built into the joint fires and surveillance variant of the Boxer would facilitate the integration of this capability.

Cross-domain. Littoral operations require land domain forces to project combat power into the other domains. The cavalry, therefore, must be able to sense, shield, shape and strike in more than just the land domain. While at face value this is a very demanding requirement, the operational framework of the disruption zone bounds the problem and provides guidance as to the capabilities required. The previous section outlined the cavalry’s contribution to the maritime domain. In the air domain, the cavalry must be able to sense and shield from sUAS and loitering munitions transiting through the disruption zone. In this regard, the Boxer CRV is introducing some incidental counter-sUAS (C-sUAS) capabilities. Specifically, the Boxer CRV’s sensor suite, active protection systems, and force protection electronic countermeasures may all have some ability to detect sUAS. The Boxer CRV’s main gun, firing kinetic energy timed fuse rounds, has the proven ability to destroy sUAS.[34] However, this incidental capability will not meet the threshold of a minimum viable capability for C-sUAS.

The Army has a project to procure a C-sUAS capability. The cavalry should be enabled by the systems procured by this project. In line with the framework of minimum viable capability, integration of standalone C-sUAS systems into the Boxer CRV (or any other platform) should be avoided due to the cost, schedule and technical risk. It would, however, be feasible to upgrade existing sub-systems such as the remote weapon station, active protection system or force protection electronic countermeasures system. Dismounted sensors and effectors, common to the rest of the close-combat force, are preferred. A minimum viable capability would require enough systems for each troop to have an active C-sUAS capability.

The cavalry’s contribution in the cyber and space domains is limited—noting that the adversary does not manoeuvre through the disruption zone in these domains. However, the cavalry must have the ability to conduct reconnaissance and surveillance in the electromagnetic spectrum. Historically, this has been conducted by specialist light electronic warfare teams. However, there is unlikely to be enough of this scarce asset to distribute through the disruption zone with cavalry force elements. A minimum viable capability, however, does not require all the capabilities that a light electronic warfare team provides. Arguably, the only essential capability is direction finding—that is, surveillance of the electromagnetic spectrum with the ability to detect threat emissions and cue a reconnaissance asset (likely sUAS) to investigate. It would be feasible to include such a capability within cavalry units without the need for scarce specialist enablers.[35] A minimum viable capability would require enough systems for each troop to have its own direction-finding capability.

Workforce. This article advocates for additional systems such as sUAS, loitering munitions, autonomous sensors, C-sUAS and direction finding. Clearly, these systems require soldiers to operate them, in addition to the crews of the mobility assets on which the systems are mounted. With the cavalry being a low priority within the Army for the provision of additional workforce, there will be inevitable tensions between the need to maximise the number of vehicles that can be crewed and appropriately manning their enabling systems. To optimise the cavalry for littoral manoeuvre, it is likely that some cavalry soldiers currently allocated to crew vehicles will have to be reallocated to become systems operators.

This will likely require amendments to the cavalry trade structure. This could include the creation of additional category skills for armoured cavalry specialists supported by professional training in relevant enabling systems. For example, soldiers would gain the qualification of ECN 060-2X Armoured Cavalry Specialist—Aerial Systems Operator, making them able to employ and manage all sUAS and loitering munitions. It may also be possible to create an additional technical specialisation for non-commissioned officers. For example, corporals would be trained as instructors in enabling systems during the Subject 2 Sergeant course. This development would complement the existing instructional courses in gunnery, communications, driving and servicing.[36]

Operational mobility. To achieve its purpose, the cavalry must have greater operational mobility than the force it supports. This, for example, is why current cavalry vehicles are wheeled while the main body is tracked. Everything else being equal, wheeled vehicles provide better operational mobility than tracked vehicles—on land.[37] However, the DSR changes this dynamic by directing that Army is to be ‘transformed and optimised for littoral manoeuvre operations by sea, land and air from Australia’. The reality is that cavalry platforms cannot manoeuvre on the sea or in the air. This limitation gives rise to the greatest challenge facing the cavalry in efforts to support the integrated force in an archipelagic environment: it must be able to manoeuvre separately from the main body even if it is operating outside the land domain.

ADF operational plans foresee the need for rapid deployment of ADF assets into the littoral environment to deny key terrain and to pre-empt an adversary. To achieve this, it is most likely that ADF force packages would be deployed (and redeployed) by maritime littoral manoeuvre vessels (LMVs). To this end, two types of the vessels are being procured, the medium (LMV-M) and the heavy (LMV-H).[38] The main body (including long-range strike and ground-based air and missile defence capabilities) would almost certainly be deployed on the LMV-H, with its larger capacity. Therefore, in order to manoeuvre separately from the main body, the cavalry needs to be optimised to travel by LMV-M. This is a significant challenge, as the LMV-M is likely to be able to carry only a single Boxer CRV.[39] Considering proposed LMV-M numbers and availability, it is unlikely that even a troop of Boxer CRVs could be manoeuvred separately from the main body in this way. Equally, while the Boxer CRV could be deployed by air assets such as the C-17A Globemaster,[40] it is unlikely that enough aircraft would be available for this to be a feasible option.

The difficulty in deploying the Boxer CRV quickly into the littoral environment is a significant issue. One solution would be to ensure that the cavalry capability is not tied only to the Boxer CRV platform. Instead, the cavalry should develop alternative mobility options optimised for rapid deployment and littoral mobility. This alternative mobility platform may be a protected platform like the Hawkei, or an unprotected platform like the Mercedes G-Wagon or surveillance reconnaissance vehicle. These platforms are already in service in a ‘light cavalry’ role with the 2nd Australian Division. Another cheap and available option is an all-terrain vehicle similar to the ultra-light tactical vehicle being introduced by the United States Marine Corps.[41] A troop of these mobility platforms could be deployed by a single LMV-M or C-17. In extremis, commercial four-wheel drive vehicles could be bought, leased or seized in location on arrival in an area of operations. This would provide the supported commander with an agile cavalry force element able to pre-empt an adversary by quickly seizing key terrain and establishing a disruption zone, to set conditions for the arrival of conventionally mounted forces.

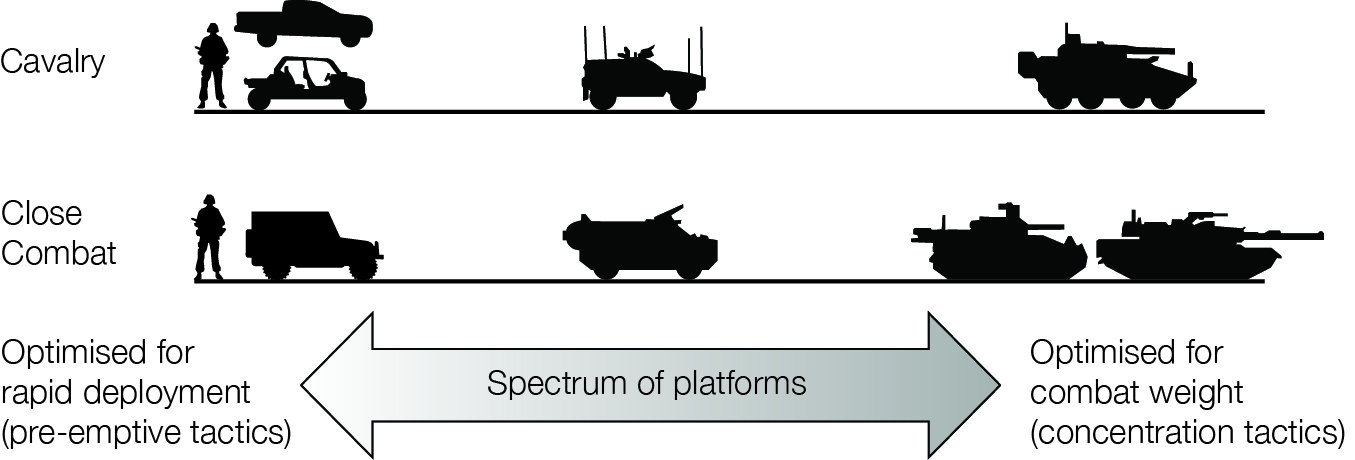

By optimising its mobile platforms—for combat weight at one end of the spectrum and rapid deployment at the other—the cavalry would mirror and complement the capabilities already used by the close-combat force (infantry and tanks).[42] Indeed, the cavalry would be positioned to match or even exceed the operational mobility of any force it may be tasked to support. Due to the common platforms, this approach would also provide synergy between the cavalry units of the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions, enabling mutual support and reinforcement. The cavalry’s need to utilise a range of mobile platforms reinforces the importance of not integrating the enabling capabilities directly into the Boxer CRV (or any other platform).

Figure 5. Spectrum of platform capabilities

Adapting the cavalry to utilise a range of mobile platforms has its challenges. However, there are examples in which it has been successfully achieved. For example, cavalry soldiers of 2nd/14th Light Horse Regiment successfully crewed up-armoured four-wheel drive vehicles while operating in Baghdad in 2010. Similarly, the 1st Armoured Regiment successfully experimented with Hawkei in a cavalry role in 2021. While demonstrating the level of flexibility inherent in the cavalry, these examples were based on unusual circumstances and had the benefit of extended warning times. The same approach will not enable the reduced readiness required for a force tasked to pre-empt an adversary’s actions through rapid deployment. What is required instead is a full-time cavalry force permanently mounted in smaller mobile platforms, able to deploy or redeploy at the short warning times demanded of the ADF’s emerging operational plans.

Not all cavalry formations need to be trained to operate across a spectrum of mobile platforms. The career model employed when B Squadron 3rd/4th Cavalry Regiment was equipped with the Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle remains suitable for this force. For that period, the training and career progression of cavalry soldiers was based on the primary cavalry platform (then the ASLAV). These soldiers then trained on the (much less complex) Bushmaster to enable them to serve temporarily with B Squadron 3rd/4th Cavalry Regiment, before returning to an ASLAV mounted unit for career progression. As with ASLAV in the past, the careers of future cavalry soldiers will be based on the Boxer CRV. However, they will be able to serve for periods on alternative mobility platforms without change to the full-time cavalry career model.

Further optimisation for littoral manoeuvre would see watercraft incorporated into cavalry force elements. These watercraft would move dismounted and autonomous force elements (with enabling systems like sUAS and loitering munitions) between land masses, as well as patrolling waterways in the disruption zone. This would not fill the role of or compete with the joint pre-landing force.[43] Rather, it would ensure the cavalry could establish a robust disruption zone in the littoral without tasking other elements of the integrated force. The integration of watercraft, however, likely exceeds the threshold of a minimum viable capability for littoral manoeuvre. It would require the procurement of new major systems, and significant change to unit structures and career models. Experimentation regarding the integration of watercraft should occur, for consideration after a baseline competency in littoral manoeuvre has been achieved.

Priorities

To optimise the cavalry for littoral manoeuvre, the Army should prioritise acquisition of ‘offensive’ systems able to sense and strike at longer ranges on both land and sea. It is these capabilities that will most raise the costs of aggression for the adversary, influence the adversary’s decision-making, and support the ends of deterrence and national defence. Capabilities that have the highest technological readiness level and are able to be introduced quickly should also be prioritised. Based on the considerations outlined in this article, it is proposed that the cavalry must be able to deliver the following effects if it is to achieve a minimum viable capability for littoral manoeuvre:

- A layered sUAS network, with each level of command enabled with sUAS, able to detect an adversary at the forward edge of the disruption zone and maintain contact through its depth, on both land and sea.

- A loitering munition system able to conduct limited strike on land and sea through the full depth of the disruption zone.

- Additional mobility options to enable pre-emptive tactics, with a more agile force element able to set conditions for the arrival of the cavalry main body in Boxer CRVs.

- A C-sUAS capability able to sense and shield from adversary sUAS and loitering munitions, with both soft and hard kill options.

- A system able to conduct surveillance in the electromagnetic spectrum, particularly a direction-finding capability to cue a reconnaissance asset to the location of any threat emissions.

- Autonomous sensors able to cover gaps in surveillance in complex terrain on land.

Endnotes

[20] Defence Strategic Review, p. 20.

[21] National Defence Strategy, p. 56.

[22] ‘6th Australian Division Cavalry Regiment’, Australian War Memorial, AWM U54268, at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U54268 (accessed 20 August 2024).

[23] Defence Strategic Review, p. 38.

[24] ‘Vingtaqs II: The Supreme Target Acquisition System’, Rheinmetall (website), at: https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/products/c4i/electro-optics/observation-and-fire-control-units/vingtaqs-ii (accessed 24 July 2024).

[25] Sarah Price, ‘Surveillance Technology for ADF Being Created in Yinnar Robotics Workshop’, ABC News, 19 March 2023.

[26] ‘Uncrewed Aerial Systems’, Department of Defence (website), February 2024, at: https://www.defence.gov.au/defence-activities/projects/uncrewed-aerial-systems.

[27] ‘Defence to Procure New Small Uncrewed Aerial Systems’, Australian Defence Monthly, 15 July 2024.

[28] ‘What Is an Average Lifespan of a Military Drone in Ukraine?’, Science and Technology News, 1 December 2022.

[29] Mitchell Payne, ‘Bullets or Weapons: Rethinking Army’s Approach to SUAS Integration’, US Army Magazine CXXXVI, no. 1 (2024): 52.

[30] Tzally Greenberg, ‘Australia Buys Tomahawk, Spike Missiles in Deals Worth $1.7 Billion’, Defense News, 23 August 2023.

[31] Simon Stuart, ‘Opening Address to the Chief of Army’s Symposium’, speech, Perth, 29 August 2023.

[32] Defence Ministers, ‘Australian Government Announces Acquisition of Precision Loitering Munition’, media release, 8 July 2024, at: https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2024-07-08/australian-government-announces-acquisition-precision-loitering-munition.

[33] ‘Switchblade 600’, AeroVironment (website), at: https://www.avinc.com/lms/switchblade-600 (accessed 20 August 2024).

[34] Kapil Kajal, ‘Australia Tests Boxers for C-UAS Capability’, Janes, 9 August 2023.

[35] Colin Demarest, ‘CACI Team Focusing on Software, Signals Following US Army Jammer Deal’, C4ISRNet, 10 October 2023.

[36] Department of Defence, Royal Australian Armoured Corps—Employment Specification—Armoured Cavalry (ECN 060) (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2016), C-1-3.

[37] John Matsumura, John Gordon IV, Randall Steeb, Scott Boston, Caitlin Lee, Phillip Padilla and John Parmentola, Assessing Tracked and Wheeled Vehicles for Australian Mounted Close Combat Operations (Santa Monica CA: RAND Corporation, 2017), p. 145.

[38] Australian Government, Integrated Investment Plan 2024 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), p. 54.

[39] Nigel Pittaway, ‘Birdon Details Land 8710 Proposals’, Australian Defence Monthly, 5 January 2024.

[40] ‘Land 400 CRVs Tested for C-17 Compatibility’, Australian Defence Monthly, 20 June 2017.

[41] Johannes Schmidt, ‘Marine Corps Systems Command Begins Fielding Cutting-Edge Ultra-Light Tactical Vehicle’, Marine Corps Systems Command (website), 7 June 2023, at: https://www.marcorsyscom.marines.mil/News/News-Article-Display/Article/3419880/marine-corps-systems-command-begins-fielding-cutting-edge-ultra-light-tactical/.

[42] This spectrum of platforms facilitates both pre-emptive and concentration tactics, as outlined by Robert Leonhard. Robert R Leonhard, Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (independently published, 2017), p. 197.

[43] While not advocated here, a possible course of action is the merging of a cavalry unit with the joint pre-landing force (currently the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment). Such a unit would be optimised for the full suite of reconnaissance and security tasks in support of littoral manoeuvre.

The enduring purpose of the cavalry is to enable the supported commander to achieve their mission. This article has argued that in littoral operations, this mission is most effectively achieved through the establishment of a disruption zone to manage the transition between the close area and the deep area, and the operational fight and the tactical fight. The cavalry sets conditions for friendly forces in the close area to influence the adversary in the deep, as well as disrupting adversary forces crossing from the deep into the close to influence the supported force. Given the dispersed nature of littoral operations, the cavalry requires an organic ability to sense and strike at longer ranges on both land and sea. It needs the ability to sense and shield from an adversary’s sUAS and loitering munitions, and the ability to conduct surveillance in the electromagnetic spectrum. To set conditions for the arrival of the main body, the cavalry needs alternative mobility options optimised for rapid deployment. It also needs a force structure optimised for littoral manoeuvre and capabilities necessary for Army to achieve an asymmetrical advantage, and enable the integrated force to execute a strategy of denial.