Army Force Structure: What has gone wrong?

Abstract

The structure of the Australian Army is the legacy of a long and distinguished history. The author argues that this force structure needs to be re-shaped to better provide high-readiness deployable capability options to Government. He advocates adopting on-line/off-line readiness cycles, consolidating Reserve units, reviewing the employment of foreign exchange officers, and reducing the number of formation headquarters.

We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

- Albert Einstein

Introduction

Our Army’s force structure is in a poor state. The Restructuring the Army (RTA) and Hardening and Networking the Army (HNA) programs represent an acknowledgement of this situation by our commanders. Our force structure is a legacy of days when there were more units to command, and both officers and soldiers alike served for longer periods. It is the legacy of the Cold War-era in which the threat was clearly conventional and the requirement for a structure that could rapidly mobilise into a corps (+) organisation took priority. Conversely, during this period of perceived peace, our Army faced constant pressure to reduce its size and consequently suffered from the effects of a ruthless cost-cutting regime. Retaining one of each type of unit became a survival mechanism for maintaining the capabilities Army would need on mobilisation.

The situation is now vastly different. We currently face a broad spectrum of threats from smaller isolated conflicts. Our priority now should lay in maintaining a full range of capabilities at high readiness, ensuring the flexibility to respond in a timely and appropriate manner to the full range of threats. This cannot be achieved with ‘one-shot’1 capabilities that cannot maintain the readiness cycles critical to professional high readiness forces.

Our current force has too many formation headquarters that sap manning resources from the units that actually need them—those we intend to deploy. We also lack a structure that makes us inherently interoperable with our anticipated coalition partners and our Reserve is a demoralised, under-strength skeleton with many of its units fighting for their very existence. We have some work to do and, as author Russell Weighly points out:

Unfortunately, without the violence of war to impart the inspiration for change through the need for survival, very few military establishments turn out capable of maintaining a degree of order in peacetime which makes change possible.2

We Know We Are Top Heavy, So Why Won't Anyone Do Anything About It?

Army’s force structure requires too many full-time senior officer positions. Within the combat arms units there are 33 full-time combat sub-units.3 For every one fulltime combat sub-unit, we have one position for the ranks of Lieutenant General to Brigadier, three positions for Colonels, sixteen positions for Lieutenant Colonels and 51 positions for Majors.4 There are 71 officers of the rank of Major and above per sub-unit before we even consider the Captains and Lieutenants. That’s almost a sub-unit of senior officers for every sub-unit of combat soldiers. The imbalance is overwhelming.

Army’s force structure is too top heavy. A 15 per cent reduction in the number of positions for Majors and above would create sufficient positions to raise another two rifle companies and a fourth tank squadron.5 The manpower liability to train and support these additional positions would be offset by a reduced liability to train and support the removed officer positions. Additionally, we would come close to solving the officer element of the Army Personnel Establishment Plan problem overnight.6

Why do we have so many senior officer positions? Because our legacy corps (+) command structure has too many formation headquarters and these require large numbers of senior officers to man them. We need to consolidate the number of brigades and remove the divisional level of command so we can cut the number of formation headquarters, reduce the number of officers we need, and use the recouped positions where they can deliver greater capability—in deployable units.

Officer Retention: The Problem is Not Supply - It Is Demand!

Army’s current force structure for officers cannot, and will not be fully manned. It is essential that we now face this fact and adopt a leaner and flatter command hierarchy. Believe it or not, officer attrition is not the problem. The average national separation rate for civilian organisations of over 5000 employees is 16 per cent7 whilst Army’s is at 13 per cent. Our retention rate is actually quite reasonable, yet we cannot, and will not, fill all our officer positions. Many of our best people have tried and failed at this impossible task. Our retention rate is superior to the national average. The real problem is not one of retention or supply, it is one of demand. Army’s time-in-rank and force structure requirements for the employment of officers are completely at odds with any realistic retention rate or sound rank structure.

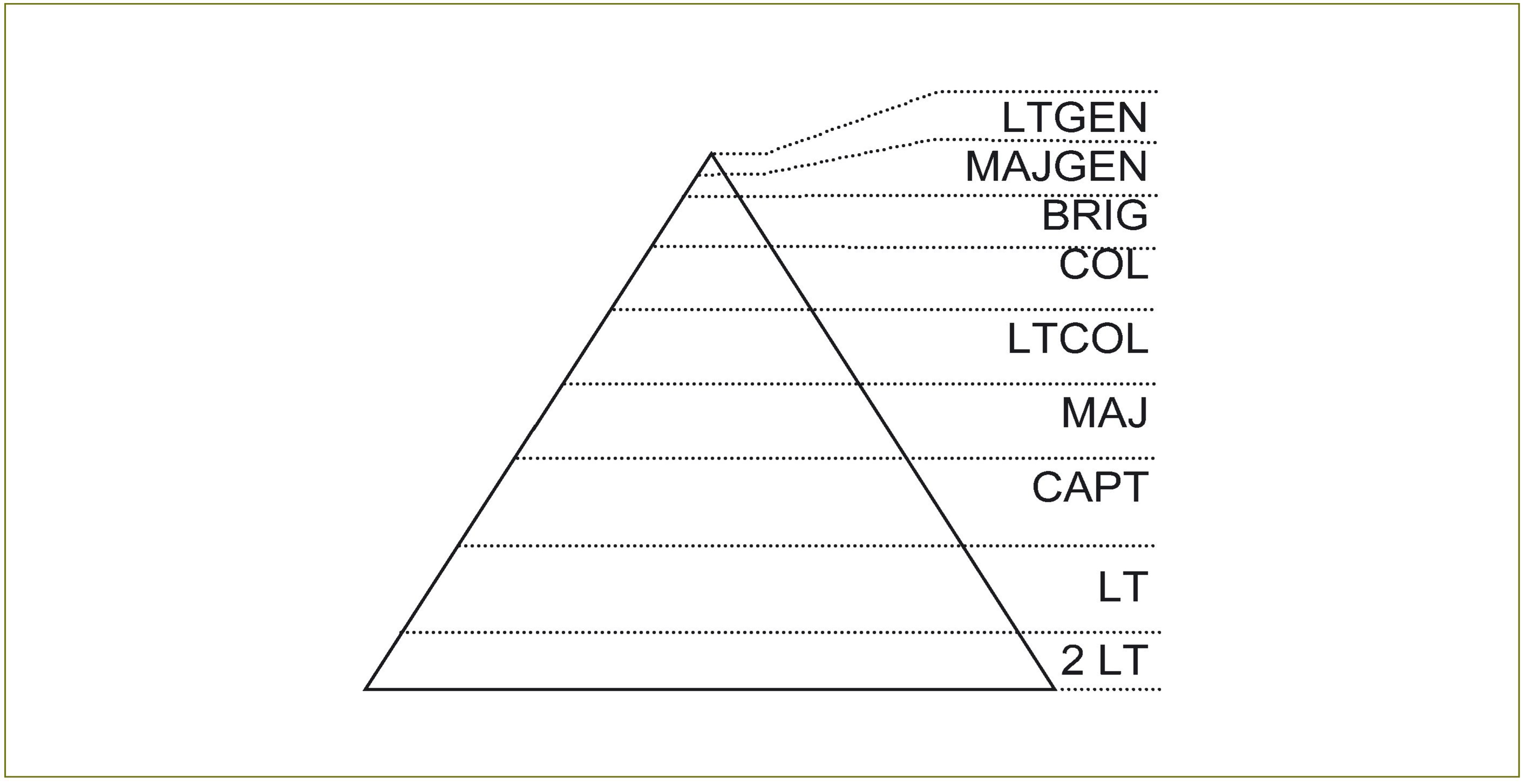

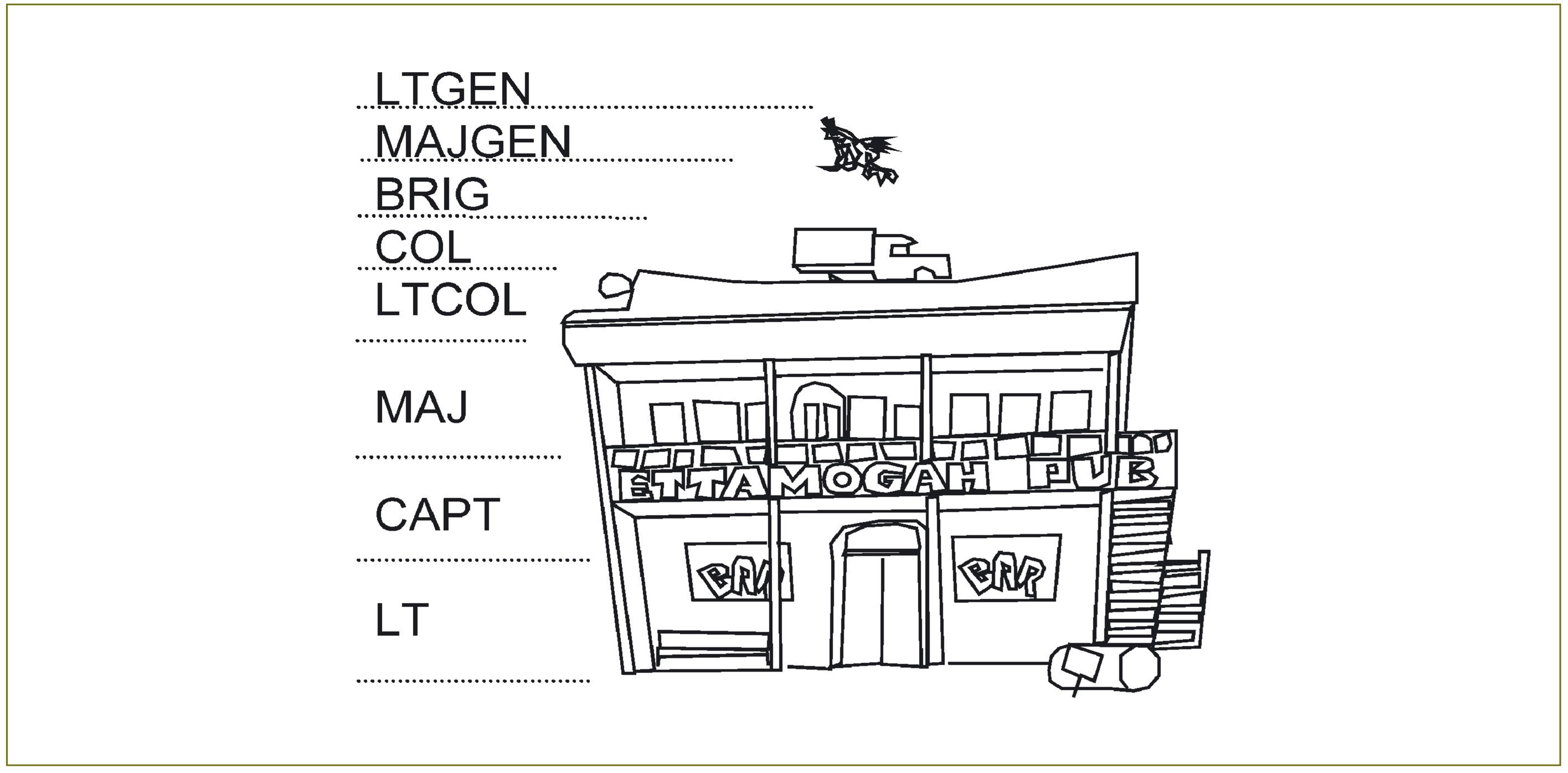

An ideal rank structure is diagrammatically depicted in the form of the pyramid in figure 1. Army’s current officer force structure, however, bears more resemblance to the Ettamogah Pub in figure 2. Army’s current force structure requires 920 Lieutenants, 1989 Captains and 1700 Majors.8 Assuming zero attrition and given the time-in-rank requirements for each rank, each Lieutenant cohort requires an average of 263 officers, each Captain cohort 331 and each Major cohort 340 officers.9 I would argue that these numbers should be decreasing as the ranks increase in seniority. We are set up to fail by our own design.

Figure 1. Ideal rank structure.

Figure 2. Current rank structure.

Within a pyramid structure (figure 1), a deliberate reduction in positions occurs as ranks increase in seniority, thus allowing for attrition and creating a competitive environment, resulting in enhanced performance. The Ettamogah Pub structure (figure 2), however, makes no allowance for any attrition and reduces competitiveness for promotion within the junior officer ranks, as promotion is almost guaranteed from Captain to Major.

The keen eye will note the inclusion of the rank of Second Lieutenant in figure 1. The removal of this rank from the full-time Army has effectively damaged the credibility of the full Lieutenant. The full Lieutenant should be viewed as an officer who, while still junior in rank, has some experience and thus can be trusted to work with less supervision. This is currently not the case. The removal of the rank of Second Lieutenant has created a ‘confidence creep’ effect that has resulted in the Lieutenant assuming the credibility that should be given to the Second Lieutenant and the Captain that of the Lieutenant. Successive years of Single Entitlement Document (SED) establishment reviews conducted in mutual isolation have gradually changed many Lieutenant positions to Captain positions resulting in the Ettamogah Pub structure.

The problem is exacerbated further by a clear inconsistency. At the Land and Training Command level, Principal Staff Officers are Colonels. At Divisional level they are Lieutenant Colonels and at Brigade they are Majors. So why is it, that at unit level, the Operations Officer (S3) is a Major whilst the Adjutant (S1), Intelligence Officer (S2) and Quartermaster (S4) are Captains? The Operations Officer position can be held by a capable senior Captain and the unit Second-in-Command can serve the role of unit Chief-of-Staff. Tradition or not, the practice of having Majors as unit Operations Officers undermines all attempts to establish a sound pyramid style rank structure and is inconsistent with the rank held by Principal Staff Officers at all other levels of command.

In some units we have the Operations Officer also dual-hatted as the support sub-unit commander. This is an unfair imposition on both the commander and their soldiers. Command is a full-time job. We need to separate these two functions and provide these support sub-units with full-time commanders free from the distractions of Operations Officer responsibilities.

When considered holistically, the problem seems quite obvious. Our current force structure requires more Majors than it has Captains to draw from and more Captains than it has Lieutenants. Where are all these extra Captains and Majors required? The answer can be found where we have Captains doing Lieutenants’ jobs and Majors doing Captains’ jobs, manning our excessive number of formation headquarters, and manning the cadre staffs of our below-strength and hollow 2nd Division.10

A One-Shot Capability Isn't - We're Not Structured For Readiness

The Army’s position contains within it an internal contradiction. How can units and brigades that are dissimilarly ‘structured, trained and equipped’ be used as rotation forces?11

The fact that a one-shot capability isn’t actually a ‘capability’ in a professional high readiness force has generally been accepted across Army; however, our force structure still doesn’t reflect this acceptance. We need to be an Army of at least ‘twos’—not just to allow the rotation of units in and out of operations, but simply because two is the minimum number of units required to maintain an operational readiness cycle in peacetime. Maintaining such a readiness cycle is critical to providing our Government with a world-class professional force at an appropriate state of readiness. Ideally, however, we need to be an Army of at least ‘threes’, if not ‘fours’. Why? Because based on our experience in Korea, Vietnam, East Timor and now Iraq, we know that to sustain a professional force overseas we need to have one deployed, one preparing to deploy, one returning/reconstituting and, ideally, one prepared for other contingencies.

Generally, with a few obvious exceptions, our Army is not structured for readiness. The 1st Brigade, for example, maintains a deployable battlegroup comprising one Tank Squadron, one Mechanised Company and one Cavalry Squadron. The question remains as to whether this is a realistic grouping. Within 1st Brigade there is only one Mortar Platoon, one battalion Signals Platoon and one Special Equipment Troop. The Brigade has only one Reconnaissance and Surveillance Platoon with dismounts, and only one Sniper Section. Which rotation of the deployable battlegroup will go without these capabilities? Will they be ‘penny-packaged’ out or are they expected to deploy indefinitely? Surely if we want a credible deployable battlegroup capability that can maintain an on-line/off-line readiness cycle, we need two identical deployable battlegroups, each with its own tanks, mechanised infantry and dedicated support elements.

We need to be permanently organised in the same way that we are most likely to deploy and —where we have an Army of at least ‘twos’—we need to rotate like units on-line and off-line across the board. Our two primary Brigade Headquarters need to be rotating on-line/off-line as well. They too are units that have administrative and training requirements that must be met before they can claim to be ‘ready’ for deployment. We need both of these Headquarters to be identically organised and equally capable of commanding light and mechanised forces. We are a ‘Battlegroup’ Army, not a ‘Brigade’ Army. These Headquarters will be required to command a mix of light and mechanised forces. We need to remember that Headquarters 3rd Brigade commanded only one of its own Infantry Battalions in the first East Timor deployment. The other two were from the 1st Brigade and one of those was a Mechanised Battalion to boot!

We're Not Structured for Coalition Operations

Every major offshore operation that the Australian Army has been involved in has been conducted in a coalition setting. While we currently train for coalition operations, we are not structured for them. If we are serious about preparing for war, we must be serious about structuring for coalition operations.

Historically, our deployed forces have been integrated operationally into British and American formations and in turn we have commanded troops from the island nations of the Pacific. Recent conflicts in East Timor, Afghanistan, the Solomon Islands and Iraq have reinforced these historical trends. These arrangements are no coincidence; they have occurred as a result of our standing treaties and/or common interests with these countries.

So why then does our Army employ the majority of its foreign exchange officers in instructional appointments teaching our doctrine? Should that really be our highest priority for employing these officers? While these exchange officers undoubtedly make a valued contribution in this role, surely we could make better use of their presence? If we plan on fighting in a coalition setting, we should have a US or British exchange officer on the staff of every deployable high readiness headquarters. Exchange officers employed in this manner would prove invaluable in the establishment of tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) that, while still uniquely Australian, would also be compatible with our potential coalition partners. In addition, these officers would bring their depth of operational experience with them, thus assisting us to establish TTPs for conflicts we are yet to experience.

Combined Arms Are Supposed to be 'Combined'

Colonel Douglas Macgregor’s book Breaking the Phalanx has proven to be one of the most influential publications in shaping the reorganisation of the US Army.12 The book highlights the historical trend for ‘all-arms’ formations to be formed at a lower level, be more mobile, and be more combined in nature. This is a response to an emptying battlespace created by increased mobility, more effective means of communication, and weapons with higher lethality and greater stand-off ranges. In 1750, the all-arms formation was the field army. In 1805 it was the Napoleonic Corps. In 1914 it was the infantry division; in 1940 it was the Panzer Division and, by the end of World War II, it was the US Combat Command, or the equivalent of a brigade. The all-arms formation of today is currently the battalion-level battlegroup.

The US Army has recently commenced a massive reorganisation focused on the creation of ‘Combined Arms’ Battalions to replace its Tank and Mechanised Battalions. Each new Combined Arms Battalion has two mechanised infantry companies and two tank companies. Each brigade is now made up of two Combined Arms Battalions, a Reconnaissance Squadron with dismounts (equal in size to our Cavalry Regiments), and an Artillery Battalion.13 US brigades are currently deployed to Iraq in this configuration.

Our Australian Army, on the other hand, still maintains a lone Tank Regiment and a lone Mechanised Battalion, while we plan to raise another Mechanised Battalion geographically displaced from its combined arms partners.14 Our fighting potential is being hampered by our arms corps-based unit structure. In contrast, by creating the Combat Service Support Battalions (CSSBs) and the Force Support Battalions (FSBs), the logistics corps have managed to see past their rivalries in order to adopt more effective unit organisations. The time has come for the arms corps to do the same.

It is not enough to simply ‘train for war’; we need to be ‘organised for war’. We claim to be a battlegroup army, but our tanks, mechanised infantry and cavalry remain in separate units despite the fact that they will be expected to fight together in high-intensity close combat. In my experience it is only when the training programs of each unit conveniently align, or during directed exercises, that these capabilities train together for this most challenging and serious task. In combined arms units, combined arms training becomes the rule, not the exception.

We also need to look at where we place our specialist support units in the order of battle. Army’s specialist units are currently commanded at too high a level. It is reasonable to assume that the largest Army formation to be deployed, short of mobilisation of the Reserve, will be a brigade (+), probably under command of a joint headquarters such as the Deployable Joint Force Headquarters (DJFHQ). If this is how we are to fight, shouldn’t all specialist units be under command of the high readiness brigades or, at the most, only one level higher?

Currently, Army’s aviation, air defence, construction engineer, geomatic engineer, electronic warfare, intelligence, and military police capabilities are held at corps level, and our surveillance and target acquisition capability is held at divisional level. It should be no surprise then that a common post-operational report recommendation is that these units should ‘train with the brigades/units more often’ or words to that effect.15 They shouldn’t just train with the brigades; they should be part of them. These units need to be placed under command of the high readiness brigades as a rule and support the wider Army by exception, not the other way around. It is under command of these brigades that they will first deploy, so it is under command of these brigades that they should be organised.

The Reserve - For a Skeleton it Consumes a Great Deal

Our Reserve is a highly valuable asset that is wasting away within our dilapidated legacy force structure. The ranks of the Reserve include some of our most skilled and motivated soldiers and officers; yet for their skills and commitment we offer them service in poorly manned, poorly resourced units and little financial incentive. Some reservists actually sacrifice their higher civilian pay when they parade with us. The Chief of Army has clearly articulated what the Reserve needs to be capable of:

Consequently, the Army Reserve must be capable of providing three levels of support to the land force: first, individuals and small units force allocated to an initial deployment in any land force contribution to meet any security challenge, at relatively short notice; second, individuals and larger units from the Reserve to reinforce and rotate second and subsequent deployments. Third, the Reserve must be capable of supplying sufficient expansion forces to meet defence of Australia tasks.16

Our Reserve has been described as a skeleton force; but for a skeleton it certainly consumes an enormous amount of resources. The Reserve currently comprises fewer than seven brigades.17 Each brigade consists of only two reserve Infantry Battalions and supporting units manned to an average of no more than 40 per cent18 and delivering one or two rifle companies each for deployment.19 Yet each of these formations maintains equipment schedules that are close to full and full-time Army cadre staff manned almost to capacity, including a total of 204 of the Captains and Majors that we are desperately short of.20 The Reserve budget is 20 per cent of the total Army budget and 5 per cent of Army’s full-time manpower is allocated to support it.21 For what the Reserve currently delivers in capability, we are not making best use of those resources. To use the words of the Joint Standing Committee in September 2000:

We recommend that all units be fully staffed to operational levels. Where a unit consists of predominantly part-time personnel it is to be staffed to 120 per cent of operational requirement.22

It is hard to deny the Committee’s logic. If anything, spans of command in the Reserve should be greater, not smaller, than in the full-time army and units should be overmanned, not manned at an average of 40 per cent strength. This is necessary to compensate for the inability of some Reserve members to parade on call-out, and the departure of members volunteering for immediate service to round-out full-time units deployed in early rotations.

We need to conduct a complete rationalisation of the Reserve force structure immediately, before the Reserve self-destructs any further. The Joint Standing Committee reported that ‘the parlous state of these Reserve formations represented the single greatest concern for [the] committee during its enquiry into the Army.’23 Furthermore, the Committee recommended that the current ‘largely hollow brigades be consolidated into highly capable brigades.’ Yet six years later, very little change has occurred since the release of that report. The number one argument for maintaining a large skeletal structure is the requirement to maintain a basis for expansion. This is the traditional role of the Reserve and, while the current strategic circumstances make it less likely to be required, it is still an important and necessary task, as strategic circumstances tend to change infinitely faster than Army’s force structure. That said, the Joint Standing Committee had this to say about Army’s mobilisation plans:

The current model used for force generation is to maintain a force structure of nine brigades. Most of these brigades are skeletal – they lack most of their staff and equipment. The Department of Defence does not resource any credible mobilisation plans to provide the necessary equipment and personnel to field these brigades. In this sense the model is a fiction.24

The Solution

Hollowness is the maintenance of organisations that are insufficiently resourced to be operationally useful. This problem persists in the Army. It consumes resources while not delivering capability in meaningful time frames. It has created the paradox that the Army can actually increase useable capability by reducing its organisational size.25

The solution to Army’s force structure woes requires a review of officer positions, a rationalisation of the number of formation headquarters and a consolidation of the Reserve. It also requires a reorganisation of our high-readiness capabilities so that they can be inherently structured to maintain rotational readiness cycles and be more prepared for coalition operations.

However, Army is quickly becoming ‘change fatigued’. We need to decide on a sound and flexible structure that can cover all conceivable contingencies, put this structure in place, and maintain it. When we do change, we need revolutionary change followed by a reasonable period of normality, rather than constant gradual change. Constant change is detrimental to the wellbeing of an organisation such as Army. The challenge lies in adopting a flexible force structure that needs minimal change to deal with contingencies as they arise.

This can be achieved by ensuring that the full range of capabilities exists for the full spectrum of conflict and that these capabilities are all held in a state of high readiness. Should a particular type of conflict arise, the suitable capability can be sent as the first rotation and, if necessary, a risk decision can be made and other capabilities temporarily re-roled in preparation for the later rotations. Examples of the successful employment of this option include the deployment of 4 RAR and 5/7 RAR (second tour) to East Timor as light battalions.

Destroy the Ettamogah Pub and Build a Pyramid

We need to reintroduce the rank of Second Lieutenant for all first appointment officer positions commencing with the very next graduating class from officer training. All officers should serve two years as a Second Lieutenant regardless of degree qualification, as the rank needs to be a reflection of experience in the Army outside of officer training establishments and not the level of education. Promotion thereafter should be based on demand, qualifications and performance, not time in rank. This is a very simple change. There is no requirement to change rates of pay, just simply the badge of rank. Second Lieutenants could retain the same pay level as current first and second-year Lieutenants. This action will raise the level of confidence in full Lieutenants and allow the reversion of some Captain positions to Lieutenant positions, thus broadening the base of the pyramid.

We also need to review all Captain and Major positions and reduce the required rank level of as many of these as possible. An appropriate start-point would be the reversion of many assistant staff officer jobs to Lieutenant or Captain and all unit OPSO positions to Captain. Where the OPSO is also a sub-unit commander, the Major should be retained as the full-time sub-unit commander and the assistant OPSO should become the OPSO. Unit Second-in-Commands should be properly qualified to do the job their title suggests—command the unit in the Commanding Officer’s absence. Our unit Second-in-Command positions must only be for Staff College graduates.

Consolidate the Number of Formation Headquarters

We must remove the divisional level of command. We need a Deployable Joint Force Headquarters, but we don’t need a Division Headquarters. By consolidating the number of brigades down from nine to six, the brigades could report directly to Land Command. The Deployable Joint Force Headquarters needs to be separated from the Headquarters 1st Division function and, along with 1st Joint Support Unit, placed permanently under command of Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQ JOC). This makes these units truly tri-Service and allows them to focus solely on preparing for their operational role. The Air Force and Navy will simply not support the tri-Service staffing of DJFHQ or 1 JSU until they are removed from the Headquarters 1st Division function.

Once this occurs, two-thirds of the current Army staff could potentially be recouped to fill vacancies elsewhere, as these units would be staffed evenly by Army, Air Force and Navy personnel. This could save an estimated 22 Major and 22 Captain positions, as well as a number of critical trade positions such as clerks and signallers.

The last time Army reorganised its higher headquarters structure was in 1971. That particular reorganisation saw Headquarters Eastern Command become what is now known as Land Headquarters; Headquarters 1st Division became Headquarters Training Command; and Headquarters Northern Command became Headquarters 1st Division.26 Guardians of the history of Headquarters 1st Division should note that Headquarters Training Command was originally Headquarters 1st Division. The title and traditions of Headquarters 1st Division could be passed on to Land Headquarters and those of Headquarters 2nd Division to Headquarters Training Command. This would preserve the proud history and prestige of these headquarters.

Consolidate the Number of Brigades

As previously discussed, Army’s nine brigades could be reduced to six: two fulltime and four reserve. The 1st and 3rd Brigades should remain in place as the fulltime high readiness brigades and include the current full-time component of 7th Brigade.27 The six-and-a-half reserve brigades should then be consolidated into four fully manned, more capable brigades. Four Reserve brigades will still provide an ample basis for expansion, whilst making better use of the available resources in peacetime.

A consolidation of the reserve brigades would not require the disbandment of reserve units or the closure of any reserve depots—a move that would be fiercely opposed, and rightly so. It requires the merging of reserve units. We need to understand that the preservation of unit traditions serves us better than following a set of antiquated rules about the way we title units. B Squadron, 3th/4th Cavalry Regiment is a good example of where a single squadron can preserve the history of two regiments if necessary.

Why not merge the 5th and 8th Brigades and call them 5th/8th Brigade? Why not use a sub-unit to preserve the title of a particular regiment while under the functional command of another regiment? What is more important: following pointless naming conventions or preserving the proud histories of units and brigades forged in two world wars? These histories are a rich source of esprit de corps and contribute significantly to the morale, and the consequent effectiveness, of the Reserve. The trick is to adopt an operationally effective structure first and foremost, and preserve the formation and unit histories at the same time by linking unit titles.

The full-time staff of what is now Headquarters 7th Brigade should assume the role and title of the Deployable Land Component Command permanently and be placed under command of DJFHQ and HQ JOC. The 11th Brigade and the reserve component of 7th Brigade should be merged to form one four-battalion Queensland brigade, and the 5th and 8th Brigades should be merged to form one four-battalion New South Wales brigade. The Tasmania-based elements of 9th Brigade should be merged with 4th Brigade to form a three-battalion Victoria-Tasmania brigade, and the South Australia-based elements of 9th Brigade should be merged with 13th Brigade to form a three-battalion Western Australia–South Australia brigade. If necessary, those Brigades divided by states could maintain a full Colonel Deputy Brigade Commander and a small slice of the Brigade staff in the state not occupied by the Brigade Commander, to represent the Reserve in that state.

While consolidating the brigades will not reduce the number of Reserve combat units, it will reduce the number of support units. The remainder will comprise four sets of well-manned and resourced brigade supporting units. Consolidation will reduce the full-time cadre staff liability and save approximately 18 Major, 33 Captain and multiple critical trade full-time positions desperately needed elsewhere in Army. Consolidation will provide the Reserve greater focus and more confidence in its role. These factors combined will result in higher morale and greater capability.

Structure for Readiness

For our force structure to become inherently ‘ready’ we need to have at least two of each deployable capability, and have these assume an off-line/on-line readiness cycle between them. We need to reorganise our eight full-time combat arms units28 into four like pairs of combat capabilities. The two full-time brigade headquarters and their supporting engineer and artillery regiment headquarters need to be identically organised and equally capable of commanding both light and mechanised forces. Similar arrangements need to be made for the two high readiness Command Support Regiments (CSRs) and CSSBs. Specialist capability sub-units—such as intelligence, military police, and electronic warfare—need to be placed under command of the CSRs for collective training and administration and should only report to their parent units on technical issues.

The Tank Regiment and Mechanised Battalion, as they currently stand, are one-shot capabilities. The concept of the deployable battlegroup has serious limitations, but has served a purpose as a transitional capability. It is now time to build upon that and take the next step. We don’t need another Mechanised Battalion; we simply need to get more out of our Tank Regiment by making it an individually deployable entity in itself. We can do this by giving it its own infantry and support troops—by making the Tank Regiment and the existing Mechanised Battalion identical Combined Arms Battalions. Reorganising these two units into identical Combined Arms Battalions will deliver a far greater capability to Army. Unit titles such as 1st Armoured Regiment (Combined Arms) and 5th/7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (Combined Arms) could be adopted to preserve unit identities.

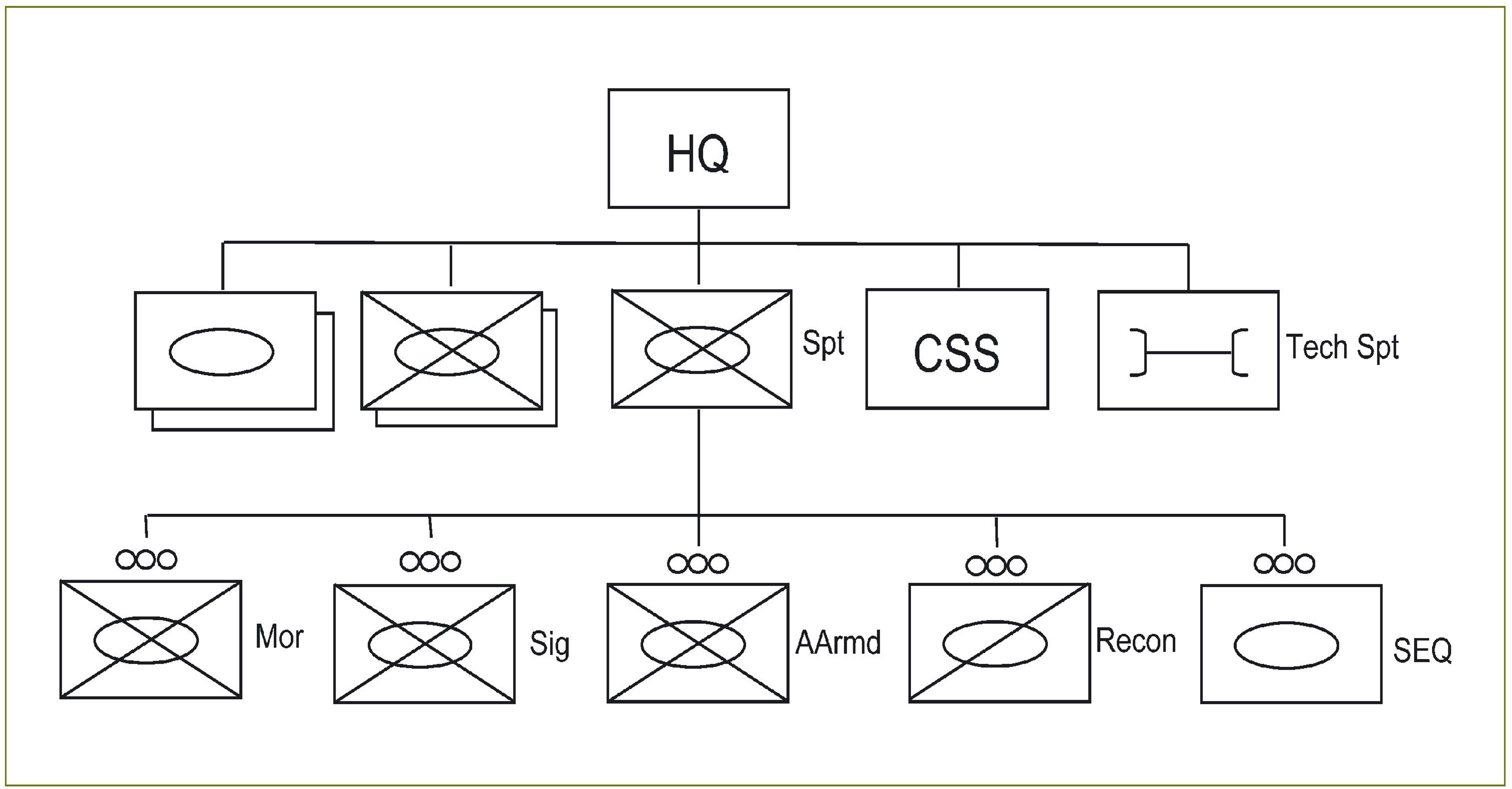

The structure for the proposed Combined Arms Battalion is shown in figure 3. Each unit would be tracked and have two Tank Squadrons (eleven M1A1 each29) and two Mechanised Companies. In addition, each unit would include Special Equipment (SEQ),30 Mortar, Signals, Reconnaissance and Surveillance Platoons/ Troops and a Sniper Section. Tanks and infantry would constantly train together and each unit would be fully capable of deploying independently, without the need for a last minute regrouping and extensive lead-up training. Logistically each of these units would be far better rehearsed and equipped to support both tanks and mechanised infantry. Both units would assume a yearly on-line/off-line readiness cycle, delivering a credible, self-contained, highly trained combined arms unit that can realistically deploy within a short time frame.

The deployment of Australian Light Armoured Vehicles (ASLAVs) to the Security Detachment (SECDET) and the Al Muthanna Task Group (AMTG) in Iraq has proven that it is sound practice for cavalry to deploy with infantry integral to its’ organisation. It is now understood more than ever before that the cavalry scout and the rifleman, while similar in capability, each have separate roles. Our operational experience has proven that the current structure of the Cavalry Regiment is not sufficiently combined arms in nature and is no longer appropriate. The Cavalry Regiment needs to have its own cavalry scouts and infantrymen.

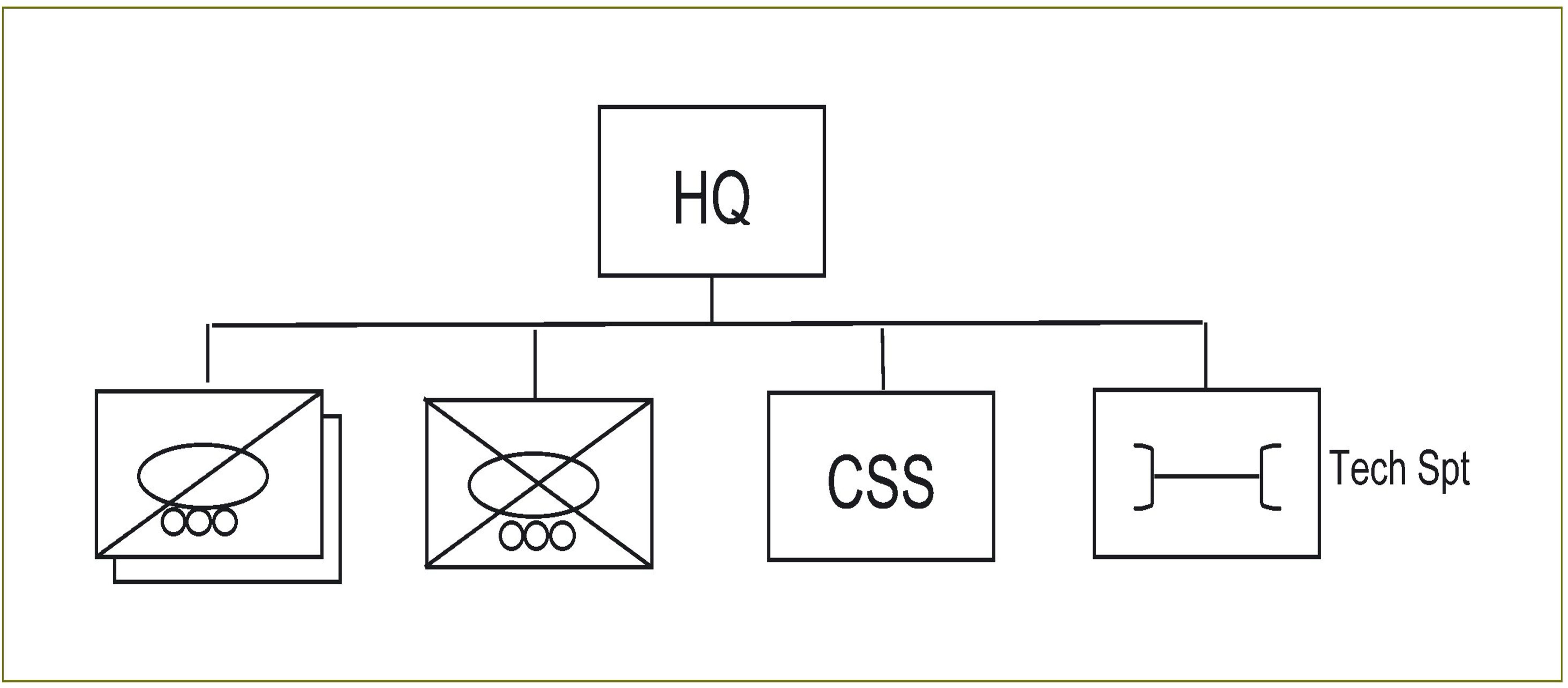

Figure 3. Combined Arms Battalion

The Cavalry Regiments need to have their own infantry. I propose we should reorganise the third squadron in each Regiment to be a Mounted Infantry Company (see figure 4). The Mounted Infantry Company could be an infantry company mounted in ASLAVs with armoured corps vehicle crews and infantry dismounts. This is not a new concept for the Australian Army as our Cavalry units started out as mounted infantry units—ie the Light Horse! This Mounted Company would perform standard infantry tasks including clearance of complex terrain, forward operating base security and dismounted patrolling of extended duration, neither of which is an entirely appropriate use of cavalry scouts.

Had our Cavalry Regiments been organised in such a fashion in 1999, we would not have had to re-role an ASLAV squadron to perform an armoured personnel carrier (APC) role for the infantry at short notice in East Timor, as such an organisation would have already existed at high readiness. Had this been the case in 2003, we would not have had to form a SECDET from separate units that had rarely trained together, because such an organisation would have already existed at high readiness. Had such an organisation existed in February 2005, we would not have had to form the AMTG from two separate units, because such an organisation would have already existed at high readiness.

We now know that our cavalry assets need to, and will, deploy with infantry. Now it is time to stop allowing corps rivalries to impede effective force structure and organise our Cavalry Regiments in the way in which we will deploy them.

Army’s current full-time Motorised Battalion needs to be joined in the motorised role by re-roling the Parachute Battalion, not as another Mechanised Battalion under the current HNA plan, but as a second Motorised Battalion. In concert with the creation of two Combined Arms Battalions in Darwin, this option would be significantly cheaper than creating another Mechanised Battalion in Adelaide. It would also create a situation where we can have two Motorised Battalions rotating on-line/off-line, which the current HNA plan does not. The rotation of these two battalions would deliver an additional highly trained infantry unit with its own protected mobility that can realistically deploy within a short notice-to-move requirement.

Figure 4. Cavalry Regiment

In order to make our high-readiness units ‘ready’ to deploy with coalition forces, each high-readiness Brigade Headquarters needs to have embedded a US and a British exchange officer holding permanent appointments on staff. We should then seek to ensure that our officers serving in reciprocal postings with the US and British armies are employed in US and British headquarters that our units are likely to serve under. Where possible, all of our high-readiness unit level headquarters also need to have an embedded exchange officer from any one of our potential coalition partners. These exchange officers should then be rotated so that units constantly experience different perspectives and contributions from these valuable officers.

MORE CAPABILITY FROM THE RESERVE

Understrength units in both the Reserve and Regular army damage morale and retention, provide a poor vehicle for training and, in the final analysis, do not provide useable capability.31

In order to increase Reserve capability, we need to attack the manning issue from both ends. First, by consolidating the number of formations and merging brigade support units we will increase the manning levels of the remaining units significantly and make better use of our limited resources. Second, we should stop giving money to our reservists’ employers and start giving it to the reservists themselves—under specified guidelines. If we charge a reserve soldier for failing to parade, chances are he won’t be seen again. Reserve soldiers react better to positive reinforcement measures. We need to introduce a parade bonus system where we reward our reservists for attending the parades we want them to attend.

Through reorganisation, the full-time Army could provide two rotations of four battlegroups each. Short of mobilisation, the Reserve could be made capable of providing the third, as well as providing the basis for expansion on mobilisation. By introducing a high readiness form of reserve service where we financially reward our reservists with a bonus for parading a minimum of 50 days of mandated training per year and maintaining AIRN compliance,32 we could increase parade attendances dramatically for relatively little cost. This does not imply a re-introduction of the Ready Reserve Scheme, but rather a higher level of commitment from existing members of the Reserve parading at existing Reserve units.

Conclusion

Army’s force structure is in a parlous state—but it can be fixed. In some areas the solutions are simple and could be addressed very quickly. In other areas it will take some detailed analysis, a willingness to try new structures, the redistribution of equipment and the relocation of some units. While the HNA process is taking us forward, we can still do more.

The Cold War is history. We need a force that maintains a complete range of capabilities at high readiness. We must make some tough decisions on the number of formation headquarters we need in order to restore sound manning levels to our deployable units and to adopt a structure that can be realistically filled by the available officers and soldiers. By removing the divisional level of command, making DJFHQ and 1 JSU truly tri-Service units under command of HQ JOC, and consolidating the number of reserve brigades, we can save an estimated 40 Major, 55 Captain and a similar number of full-time support staff, releasing desperately needed full-time positions. The reduction in rank of assistant staff officer positions and the change of unit OPSO positions from Major to Captain will save even more positions.

Currently our on-line force consists of a Light Battalion and a questionable 1:1:1 Battlegroup capability. With some modification to force structure within our existing resources, we could have an on-line force consisting of a Brigade Headquarters, a Combined Arms Battalion, a Cavalry Regiment, a Motorised Battalion, and a Light Battalion, all with supporting arms and services at any one time when forces are not committed overseas. Meanwhile, an identical force would be off-line reconstituting in preparation for returning to high readiness (refer Table 1).

We need to adopt on-line/off-line readiness cycles across the board with our fulltime deployable units. We need to be better prepared for coalition operations and review our priorities for the employment of our foreign exchange officers. Finally, we need to breathe life back into the Reserve by consolidating its force structure while still preserving its proud unit and formation histories. These should be the next steps in the move towards a Hardened and Networked Army. It is our duty to deliver to the Government of Australia and the Australian taxpayer the greatest amount of capability possible from the resources they allocate to us. The preservation of existing inefficient unit structures must not be held above this obligation.

Table 1. Proposed readiness rotation model

| On-line force | Off-line force | Reserve force |

| Brigade Headquarters | Brigade Headquarters | Light Brigade Group (4 Bns) |

| Combined Arms Battalion | Combined Arms Battalion | Light Brigade Group (4 Bns) |

| Cavalry Regiment | Cavalry Regiment | Light Brigade Group (3 Bns) |

| Motorised Battalion | Motorised Battalion | Light Brigade Group (3 Bns) |

| Light Battalion | Light Battalion | |

| Multi-Role Aviation | Multi-Role Aviation | |

|

Battlegroup Artillery Regiment |

Battlegroup Artillery Regiment |

|

|

Survl & Tgt Acquisition Battery |

Survl & Tgt Acquisition Battery |

|

| Engineer Regiment | Engineer Regiment | |

|

Command Support Regiment (+) |

Command Support Regiment (+) |

|

|

Combat Service Support Battalion |

Combat Service Support Battalion |

|

| Force Support Battalion | Force Support Battalion |

Endnotes

1 One-shot capabilities are those units that exist in isolation without other identical units that can be used for rotation forces. One-shot capabilities cannot be rotated and must either remain deployed indefinitely or return without replacement.

2 Russel F. Weighly, Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany, 1944–1945, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1970, p. 730.

3 1 RAR: 4; 2 RAR: 4; 3 RAR: 3; 5/7 RAR: 3; 6 RAR: 3; 1 AR: 3; 2 CAV: 3; 2/14 LHR: 2; B SQN ¾ CAV: 1; SASR: 3; 4 RAR: 4.

4 Complete Officer Position List, 30 Mar 2006.

5 This amounts to 303 positions.

6 The Land Command Army Personnel Establishment Plan 06 Working Group, which was convened on 18 August 2004, identified that, in 2006, Army would fall 15 per cent short of its requirement for Majors.

7 Alisha Carr, ‘The battle for hearts and minds’, Army News, 20 June 2002, http://www.defence.gov.au/news/armynews/editions/1053/story05.htm, accessed on 24 June 2006.

8 Complete Officer Position List, 30 March 2006.

9 The time-in-rank requirements are: three years for degree-qualified Lieutenants; four years for non-degree Lieutenants, six years for Captains; and five years for Majors.

10 Parliament of Australia, From Phantom to Force: Towards a more efficient and effective Army, Joint Standing Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Report into the suitability of the Australian Army for peacetime, peacekeeping and war, released 4 September 2000, p. 109.

11 Ibid, p. 119.

12 Douglas A. Macgregor, Breaking the Phalanx: A New Design for Landpower in the 21st Century, Praeger Publishing, USA, 1997.

13 Janes Defence Weekly, 9 June 2004.

14 The desire to base a battalion in Adelaide for retention purposes is based on sound reasoning but runs the risk of causing a functional dislocation. We don’t need another Mechanised Battalion; we simply need to get more out of our Tank Regiment by making it an individually deployable entity in itself. We can do this by giving it its own infantry and support troops—by making the Tank Regiment and 5/7 RAR identical Combined Arms Battalions.

15 Post Operation Report: Operation WARDEN 20 Sep 1999–15 Feb 2000, Headquarters 3rd Brigade, 2000.

16 Lieutenant General Peter Leahy, ‘The Australian Army Reserve: Relevant and Ready’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, Winter 2004.

17 4 Brigade, 5 Brigade, two-thirds of 7 Brigade, 8 Brigade, 9 Brigade, 11 Brigade and 13 Brigade.

18 From Phantom to Force, p. 109.

19 Ready reaction force Company and a force protection Company group.

20 Complete Officer Position List, 10 Sep 2004.

21 Leahy, ‘The Australian Army Reserve: Relevant and Ready’.

22 From Phantom to Force, p. 189.

23 Ibid, p. 109.

24 Ibid, p. 124.

25 Ibid, p. 105. Emphasis added.

26 Origins of Land Headquarters, published on the Land Headquarters intranet site 2004.

27 Issues relating to the geographical displacement of these Brisbane-based full-time units would be dealt with in the same way that the Townsville-based 3rd Brigade commands the Holsworthy-based 3rd Battalion.

28 1 x Tank Regiment, 2 x Cavalry Regiments, and 5 x Infantry Battalions.

29 The total number of tanks required would be 46 (four squadrons of 11 and 2 tanks for each unit headquarters). Army currently plans to acquire 59 M1A1 tanks. This will leave more than twenty per cent of the tanks for special equipment (SEQ), training and maintenance support roles.

30 SEQ Troop will probably be removed with the purchase of the M1A1 as, at this stage, no SEQ equipment is to be purchased.

31 From Phantom to Force, p. 114.

32 A $5000 per annum parade bonus per member, based on a force of 3000, would cost only $15 million a year; however, the capability it would deliver would make it money well spent.