Operation OKRA Operational Analysis

Australian Operations to Degrade the Islamic State—2014–2024

Executive Summary

Beginning in 2014, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) was committed to Operation Okra in the Middle East, with the aim of degrading the Islamic State, ISIS, or Daesh. This objective was ultimately achieved in 2018, although ongoing operations monitoring the threat have since continued. It has now been a decade since the commencement of this intervention, which the ADF formally concluded in December 2024. The Chief of Defence Force (CDF) acclaimed the ‘excellent work’ of some 4,800 service men and women who served on Operation Okra and ‘made a tangible and important contribution to global security’.[1] While such conclusions are likely correct, little is offered by Defence media releases to truly assess the veracity of CDF’s praise.

Meanwhile, the Islamic State remains. Throughout 2024, isolated guerrilla attacks continued throughout Iraq. One Islamic State ‘franchise’, the Islamic State Khorasan Province (IS-KP), successfully mounted an attack against Russia’s Crocus City Hall on 22 March 2024. Further IS-KP attacks in Europe were successfully prevented. Rounding out the year, ISIS successfully ‘inspired’ an attack in New Orleans.[2] These events demonstrate that ISIS remains a latent threat, capable of external operations (EXOPs) outside the Middle East.

This paper undertakes an operational analysis of the ADF’s contribution to operations against ISIS in Syria and Iraq, particularly focusing on the heightened period of combat operations from 2014 to 2018. It does so with an aim to inform the strategic planning and conduct of current and future counter-terrorism efforts, such as those undertaken by Operation Augury—the ADF framework in support of efforts to counter terrorism and violent extremist organisations around the world.[3]

There is an evident need for such understanding. When it first captured the West’s attention in 2014, the Islamic State was more than a ‘terrorist’ group, and the Middle Eastern conflict in which it was involved was much more than a civil war. Indeed, by 2014, the conflict in Syria had become a messy failed revolution spilling over into Iraq that grew into a proxy civil war involving the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, Turkey and Jordan. This dynamic was prominent in the surprising success of Turkish-backed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in December 2024 in Syria, seemingly resolving the conflict.

By examining Australia’s recent experience in the Middle East, this paper reflects critically on the planning challenges that emerge from engaging an irregular or non-state adversary (such as the Islamic State) in the context of multi-party strategic competition. While Western military operations against ISIS were ultimately successful, a contemporary appreciation of the competitive environment in which other nations pursued their proxy strategies seemed incomplete at times—perhaps even naïvely absent. Western actions did not always translate into effective strategy; our understanding of our adversary was incomplete, and we created counterproductive second-order effects from our actions. There are therefore clear lessons to be learned from this conflict.

Curiously, there has been little published by Australian authors examining the military challenges, personal experiences, and lessons from Australia’s contribution to national security efforts to counter the Islamic State. This paper aims to remediate this gap.

As the US and Australian national security communities pivot to an era of major power competition, drawing lessons from our past decade of engaging in competition is a curious oversight. Beginning with the Arab Spring in 2011, the decade of conflict in the Middle East has seen competition between the US and Russia, the Sunni and Shi’a branches of Islam, Qatar and the Gulf States, and Turkey and Russia. These examples demonstrate that major and middle powers wish to avoid direct conventional warfare which risks runaway escalation. Major and middle powers avoid the risk of runaway escalation of tension by attempting horizontal escalation directly and indirectly (i.e. via proxies). In so doing, states that are in competition with one another exploit opportunities to impose costs and to undermine the interests of their competitors. Conflict environments provide such opportunities.

This is not new. As Henry Kissinger identified in 1955:

But is there any deterrent to Sino-Soviet aggression other than the threat of general war?... Our immediate task must be to shore up the indigenous will to resist, which in ‘grey areas’ means all the measures on which a substantial consensus seems to exist … Thus, our capacity to fight local wars is not a marginal aspect of our effective strength; it is a central factor which cannot be sacrificed without impairing our strategic position and paralysing our policy.[4]

The relevance of this paper’s analysis to today’s environment of heightened geopolitical competition is evident in the increasing proclivity of states to compete via irregular proxies. The ADF, however, has no publicly available policy guidance that highlights the threat of proxy conflicts and how to appropriately respond.

The Australian Government has responded to contemporary strategic challenges with the Defence Strategic Update 2020 and the Defence Strategic Review 2023. This Defence planning documentation is, however, almost exclusively orientated toward major platform acquisitions—those capabilities required for major conventional warfare (i.e. ‘respond’ tasks), which are of much less utility to the land-based, irregular wars likely to arise from proxy competition (i.e. ‘shape’ tasks). A tension thus emerges between the Defence investments in ‘shape’ tasks versus ‘respond’ tasks.

By raising lessons as to how the ADF can more effectively engage with irregular or non-state actors, this paper aims to help mitigate the opportunity costs that exist where defence policy is sparse, and thereby inform strategic policy options for government. While the intended audience is primarily Australian military officers, the paper’s arguments are also expected to contribute to allies’ understanding of our common challenges in countering today’s proxy and irregular warfare challenges.

Introduction

There are a number of organised groups that are intent on attacking American soldiers … We don’t believe them to be under a central leadership and we are taking appropriate action to deal with the threat. This is not a resistance movement.

Lt. Gen. William Wallace, commander of the US V Corps in Southern Iraq in July 2003[5]

Western militaries have a track record of misunderstanding the use of non-state armed groups, or irregular actors, as a component of a state’s national security strategy. Proxy and irregular warfare were tools in Saddam Hussein’s arsenal. Documents captured by the Israeli Army in Lebanon in 1982 show that Iraq provided support to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO).[6] A Sa’iqa (lightning or thunderbolt) course enhanced the PLO’s unconventional capabilities and was hosted in Baghdad (the course was also offered in Moscow and Syria), involving so-called ‘special forces’ training.[7]

Inspired by the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood staged an uprising in 1979–80 against the Syrian Hafiz al-Assad regime, centred on the city of Hama. Iraq provided ‘covert support to the Brotherhood, particularly in Aleppo’.[8] This proxy war with Syria occurred in the context of the concurrent Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s, a regional competition for hegemony in the Middle East. During the Iran–Iraq War, Saddam also supported the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (DPKI) and the Mujahideen e-Khalq (MEK) to undermine the Iranian war effort.

Following the 1991 Gulf War, Saddam learned from his defeat. In 1994, the Fedayeen Saddam was established, a paramilitary force under the command of Saddam’s son, Uday. Ultimately, this force would come to number between 25,000 and 40,000 men.[9] This paramilitary force effected a layered defence, with the innermost layer, located in the cities, called al-Muqawamah (The Resistance). The goal evolved to create ‘Mogadishu on the Tigris’ using relatively autonomous groups cooperating with each other on an ad hoc basis.[10]

Commencing in August 2002, weapons caches were established in the countryside and throughout Iraqi cities.[11] In September of that year, some 1,000 selected intelligence and special operations officers undertook training at the two Fedayeen training camps in Salman Pak and Bismayah.[12] Fedayeen numbers were bolstered by the recruitment of pan-Arab volunteers who had worked or studied in Iraq prior to the commencement of the war, as well as thousands of Syrians who were recruited and who subsequently infiltrated Iraq.[13]

These Fedayeen were coordinated by an underground resistance structure, based upon five-man cells, and led by General Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri.[14] External leadership of this resistance enjoyed sanctuary in Damascus. At its peak, the resistance included 14,800 former Ba’athist regime soldiers, officers and officials on full-time combat operations. Up to 100,000 members of the former Mukhabarat secret police might be added to that list, likely performing underground and auxiliary intelligence functions.[15] At the commencement of the insurgency, US intelligence services ‘estimated that al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)-aligned foreign fighters were generally believed to have been no more than two to five percent of the overall resistance’.[16] Over time, however, organisational evolution, atrophy of former regime elements, and tactical alliances blurred this ratio.

AQI established a sanctuary within Fallujah, exploiting popular grievances against the US occupation that were fuelled by the violent American suppression of local protests on 28 to 30 April 2003.[17] AQI worked pragmatically with resistance groups to accelerate the insurgency and seize Fallujah, creating an internal sanctuary area as well as reinforcing a public narrative of spiralling insurgency.

Lieutenant General Wallace (quoted at the beginning of this chapter) misunderstood the threat of Iraq developing irregular actors to operate against its neighbouring countries. In reality, a resistance movement was deliberately created by the Ba’ath Party to impose costs upon an unsuspecting US Army. Wallace’s failure to properly understand the adversary was a common one at the time, a failure to which much of the anguish of the past 20 years of conflict in the Middle East can be ascribed.

Situating the Conflict in the Levant

This chapter explores the key policy challenges that the Operation Okra intervention presented to Australia, building on the history of the Levant—the geographic region of the central Middle East encompassing Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel.

This analysis primarily focuses upon the period 2014 to 2018, which saw the emergence of Islamic State (also termed ISIS or Daesh) as a Western foreign policy issue through to its territorial defeat. The period concludes with the challenge that arose when Sunni extremism was replaced by Iranian-sponsored Shi’a terror and patronage networks (termed the Iranian Threat Network, or ITN). The ITN thereafter assumed the role of forefront foreign policy challenge in the Middle East, in the form of Hamas’s war with Israel, the Houthi threat to maritime shipping in the Red Sea, Iranian-aligned militia groups dominating the Iraqi political scene, and the conduct of direct Iranian strikes against Israel on the night of 14 April 2024. This context is important as it describes the pathway to the precipice posed by an Israeli–Iranian war: the closest the region has come to a major conventional conflict since the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The threat of regional conflagration was subsequently realised in June 2025.

The emergence of Islamic State in 2014 created what were seen at the time as unique foreign policy dilemmas that are curiously under-recognised today. First, Islamic State demonstrated a technical sophistication in operations in the cyber domain beyond what Western policymakers dismissively ascribe to non-state actors. It was a ‘digital caliphate’ with technical proficiency underpinning its comprehensive propaganda wing and ability to coordinate EXOPS via ‘inspired’ attacks.[18]

Second, and leveraging the first point, a non-state armed group was simultaneously creating challenges in the ‘deep’ battlespace of the Middle East, the ‘close’ battlespace of the South-East Asian region and the ‘rear’ of domestic intelligence and policing challenges within Australia. Traversing these regions were the Australian foreign fighters—those who travelled to join Islamic State—who contributed to the operational threat overseas, and who would also pose a threat to national security upon their return.[19] Spanning such linkages were funding flows, remote radicalisation efforts, and the sharing of tactics, techniques and procedures that improved the adaptability of Islamic State ‘franchisees’. The rhetoric of whole-of-government approaches became reality, as no single department or agency had the required authorities, mandate or resources required to address this global challenge.

Third, the overlapping influences of middle and major powers (who were competing through their chosen proxies) further complicated the situation. Indeed, it is difficult to accurately define the conflict as a ‘counter-terrorism’ effort, an insurgency, a muddled proxy war, or something in between. In actuality, it was all of these things.

More recently, attacks by Islamic State Khorasan Province (IS-KP or ISIS-K) against Russia in 2024 and the inspired attack of New Year’s Day 2025 in New Orleans demonstrate the enduring threat posed by transnational terrorist organisations. As the Institute of Economics highlighted in their 2024 Global Terrorism Index report, the ‘epicentre of terrorism has shifted out of the Middle East and into the Central Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa’.[20] Deaths from terrorism are increasing, now at the highest level since 2017, and Islamic State remains the deadliest terrorist group.[21]

The military response to the challenge posed by ISIS specifically, and the Iraqi insurgency in general, highlights the problem with the overuse of ‘terrorism’ as a label, since it elevates the phenomenon of terrorism to a strategy. From the outset of the Iraq insurgency in 2003, there was a tension between whether the violence was being driven by former Iraqi Ba’athist party members (and hence indicative of a resistance) or al-Qaeda (and therefore indicative of a terror campaign).[22] On balance, the evidence pointed initially towards the former. Over time, the distinction was blurred by the incorporation of ex-Ba’athists into al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and AQI’s organisational affiliations with the panoply of insurgent groups in Iraq.

Further tensions are evident. The designation of the Iraqi Shi’a militia, Kata’ib Hezbollah, as a US Department of State-listed foreign terrorist organisation would suggest this group was regarded as a terrorist group, yet the Iraqi government would identify it as state-authorised Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) and therefore allies in the war against Islamic State.[23] A similar difference of opinion mired the US–Turkish relationship due to the partnership between the US and the Kurdish Partiya Yekîtya Demokrat (Democratic Union Party (PYD)) militia. This relationship was problematic for the Turkish government, who viewed the PYD as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) terrorist movement.

Overuse of the label ‘terrorism’ risks confusion as to the strategic significance of the threat. Hoffman observed:

Terrorism is a purposeful human political activity which is directed toward the creation of a general climate of fear, and is designed to influence, in ways desired by the protagonist, other human beings and, through them, some course of events.[24]

Simplistically designating ISIS as a terrorist organisation inverts what we typically mean by this term: a clandestine group fighting for survival. The Islamic State was instead, in 2014, better described as a rogue political entity that was trying to function as a state.[25] In contrast, the Assad regime had long sponsored terrorism and, by 2011, might have been viewed as having lost its legitimacy to govern. States were operating in ways we would associate with non-state revisionist actors; non-state actors were operating in ways we would associate with states.

In the context of these challenges of terminology, and with reference to events in the Middle East, former US military officer Liam Collins notes:

The group [ISIS] did not fit neatly into traditional analytical categories: it was a pseudo-state, a terrorist group, and an insurgency simultaneously. This complexity both complicated analysis of the organisation’s rise and challenged transitional metrics for determining progress and victory in the war against them.[26]

A similar criticism could today be levelled towards the challenges posed by Hamas, the Houthis, or Kata’ib Hezbollah.

The reality is that irregular or non-state groups may operate across a spectrum, from civil disobedience to radicalised terrorism. In some situations, irregular groups may seek to create a climate of fear and thus employ terrorist techniques to pursue their ends because they may be too weak to exert other forms of control, or because they seek to influence the domestic audiences that undermine a military force. Over time, irregular groups may grow in strength to the point where they wage insurgency. Importantly, irregular groups may also deliberately abstain from tactics of terrorism if they recognise that it undermines the group’s legitimacy in the eyes of its relevant population. To conflate terrorist radicalisation with recruitment into broader irregular groups is misleading and is a challenge that the national security community needs to resolve.

Strategic Purpose

Australia’s military response to the threat posed by Islamic State was known as Operation Okra. It was a component of a US-led coalition commitment termed Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). Examining the challenges involved in engaging irregular adversaries such as ISIS can inform both military and policy planning efforts to meet future threats. With this frame of reference, this analysis focuses on four related ways that military forces can engage with irregular forces and proxy warfare to achieve strategic objectives:

- The employment of air power against an irregular adversary

- The utility of ‘decapitation’, targeting’ or ‘counter-network operations’ against an irregular adversary

- Proxy warfare through capacity-building and provision of battlefield support

- The mechanism and utility of information operations.

President Obama’s seemingly dismissive quip that ISIS was a ‘JV’ (junior varsity) organisation certainly didn’t age well. That ISIS ultimately survived two furious applications of Western military force (2004–2010 in its earlier designation as al-Qaeda in Iraq, and again in 2014–2018) underscores the potential resilience of irregular organisations operating within a supportive population. This resilience matters when considering the contemporary challenges posed within the under-governed spaces controlled by Islamic State Khorasan Province (IS-KP) in Afghanistan; Islamic State Sahel Province (IS-SP, also termed Greater Sahara) in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso; and Islamic State in Somalia.

An Introduction to Irregular Proxy Warfare

The conflict against ISIS has occurred within a decade characterised by major revolutionary uprisings across the Arab world, involving at least 16 of the 22 Arab states experiencing national protests or upheaval.[27] This broader political change has fuelled the development of proxy relationships as major and middle powers compete for strategic influence.

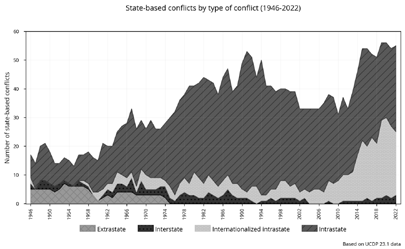

Although the ADF has experience fighting irregular forces in Timor-Leste, Solomon Islands, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, irregular warfare theory is generally absent from Australian professional military education and Defence policy documents.[28] This gap exists despite an increasing frequency of ‘internationalised intrastate’ conflict (i.e., proxy warfare involving non-state actors).[29] This trend is shown in Figure 1.1 below. In 2017, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) recorded the highest number ever of non-state armed conflicts (85). The previous peak was in 2000 at 47 non-state armed conflicts.[30]

Figure 1 drawn from UCDP data[31]

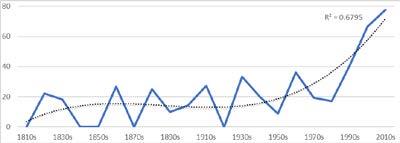

Accompanying an increasing trend towards irregular conflicts is a parallel trend towards the involvement of foreign fighters in armed conflict.[32] Foreign fighters may be state sponsored or diaspora supported, or they may be self-motivated. For example, the Tamil Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were financially well supported by a sizeable Westernised Tamil diaspora. This phenomenon of foreign fighter mobilisation flouts regulation. States may deliberately exploit this ambiguity when they support ‘volunteers’ to travel to support a given proxy, all the while claiming such individuals are acting of their own free will. Although a detailed analysis of this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this paper, the increasing number of foreign fighters (shown in Figure 1.2 below) is likely being facilitated by the increased prevalence of information-age technologies, such as social media coupled with smartphones.[33]

The trend is provided by the dotted line with a high R-squared value of variance.[34]

The Gap

In general terms, there is a literature gap regarding the examination of irregular and proxy warfare, such as that experienced by the ADF on Operation Okra. A measure of this gap can be gauged by a review of Australia’s primary national security document, the Defence White Paper (or equivalent), over the past 45 years. The outcomes of this analysis are shown in Table 1.1 below. It demonstrates the absence of any focused analysis of non-state actors, with no explanation of the strategic objectives such threats pursue.

| Defence Policy Paper | ‘Proxy’ | ‘Irregular’ | ‘Unconventional’ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 (termed National Defence Strategy—NDS) |

No mention | No mention | One mention in explaining ‘asymmetry’ |

|

2023 (termed Defence Strategic Review—DSR) |

No mention | No mention | One mention in explaining ‘asymmetry’ |

|

2020 (termed Defence Strategic Update—DSU) |

No mention | One mention in a temporal sense only | No mention |

| 2016 | No mention | No mention | No mention |

| 2013 | No mention | No mention | No mention |

| 2009 | No mention | One oblique mention | Twice obliquely mentioned |

| 2000 | No mention | One oblique mention | No mention |

| 1994 | No mention | No mention | No mention |

| 1987 | No mention | No mention | One oblique mention |

| 1976 | No mention | No mention | No mention |

The problem of limited intellectual inquiry and debate about these facets of contemporary warfare—irregular (non-state actors), proxy warfare as a component of competition, and foreign fighters—is that a soldiers’ or officers’ personal experiences become their understanding of the war. This blinkered perspective then risks a situation in which an understanding of the war becoming their understanding of warfare in general. This analysis responds to this gap.

Background: the Context for Operation Okra

One of the most notable geopolitical trends of the last five years has been the growing number of states intervening in and shaping conflicts to advance their own foreign policies and strategic agendas … powers such as Iran, Israel, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) intervening in multiple conflicts across the world … Most have supported local allies or partners or proxies … this trend has been on full display in several armed conflicts in 2020 and early 2021.[35]

In 2014, Australia and its Western partners characterised the international response to the conflict in Syria and Iraq as ‘the military defeat of Islamic State’.[36] Yet ‘ISIS is a symptom’ of broader Middle Eastern social and political unrest, and therefore the military response required nuanced understanding of the international, domestic and local governance competitions occurring between sectarian and political power structures.[37] There is little evidence of efforts to address such drivers of conflict. This chapter examines these and broader issues that framed the strategy that underpinned Operation Okra.

Operation Inherent Resolve

The US military mission for OIR was ‘by, with and through regional partners, to militarily defeat ISIS in the combined joint operations area (Iraq and Syria) in order to enable whole-of-coalition governmental actions to increase regional stability’.[38] This mission statement articulates a proxy strategy—a point unrecognised by Australian policy as seen in the previous chapter. The stated purpose of ‘increased regional stability’ also demands attention: defining success as such would suggest that now that the mission is complete, the Middle East is more stable it was before the emergence of the Islamic State. Military success defined in such terms is vague at best.[39]

Speaking soon after his deployment in 2014 to Iraq, Major General (Ret.) Pittard described the situation on the ground as highly ambiguous. He observed that no one could answer the questions: ‘What is the mission? The desired endstate’?[40] Former US Secretary of Defense Ash Carter amplified these concerns, describing the situation in December 2014 as ‘lacking a comprehensive, achievable plan for success … clearly articulated objectives or a coherent chain of command for the operation’.[41] In sum, for at least the first three to four months, OIR lacked a coherent strategy.[42]

Ultimately, Secretary Carter framed America’s mission objectives in terms of deep, close, and rear strategic outcomes. Specifically, he conceptualised the mission as dealing ‘ISIS a lasting defeat in its homeland of Iraq and Syria, eliminating the cancer’s parent tumour; combatting metastases in places like Libya and Afghanistan; and protecting our homeland from ISIS terror’.[43] In December 2015, Secretary Carter testified to the Committee on Armed Services that ‘our strategy is to destroy ISIL in Syria and Iraq and anywhere else it arises’. While simplified for public consumption, this statement gives one pause due to its open-ended nature. The statement also lacks clarity as to what ‘end’. In other words, the strategy lacks the clear political purpose that Clausewitz would prescribe for such military action.[44] Further, commentary regarding an intention to destroy the Islamic State ‘anywhere else it arises’ is at odds with the ongoing existence of the franchise in Afghanistan, Somalia and the trans-Sahel.

Operation Okra

The Australian response to the threat posed by ISIS was framed by then Attorney-General George Brandis on 10 September 2014 as a collective self-defence of Iraq.[45] The mission of the Operation Okra intervention was to ‘degrade, destroy and defeat’ ISIS.[46] In this context, the purpose of Operation Okra as ultimately defined in 2019–20 is notably different from that defined in 2014. The purpose of Operation Okra was ‘ADF operations in Iraq and Syria to support the coalition response to the Iraq crisis, including the deployment of forces to disrupt and degrade Daesh [IS]’.[47] This change in language intimated a recognition that military intervention was incapable of destroying the Islamic State movement—a view that has been borne out by subsequent events.

Despite such modifications to the mission mandate, speculation remains around the policy basis for Australia’s military intervention. Parliamentary researcher Renee Westra noted that there has been ‘no substantial public discussion or parliamentary debate about any long-term plan or strategy in Syria or Iraq’.[48] Interlinked issues such as ‘aid and reconstruction efforts’ and the future role of Assad’ remain unaddressed’—facts on the ground having decided the result in December 2024.[49] In economic terms alone, the ‘cumulative real cost’ of operations against ISIS in Iraq from 2014–20 was estimated by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute to be approximately $1.3 billion.[50] Allan Behm argued that for such a cost, Australia’s net military result of Operation Okra is ‘a presence in search of a policy’.[51]

Broader Perspectives

The timing of the US and Australian interventions in Syria and Iraq warrants attention. While the execution of American James Foley in August 2014 attracted political attention, it was the coincidental pressure of the ISIS military expansion upon the security situation in Baghdad that prompted the US to consider the evacuation of its non-combatant embassy staff. These concerns were reinforced when genocidal violence was undertaken against the Yazidis.[52] These rapidly shifting dynamics prompted the US intervention and presence in Iraq which, in turn, informed subsequent planning to counter the ISIS threat.

When juxtaposed with events unfolding on the ground, the timing of the US intervention suggests that deeper political pressures were also at play. Specifically, there was a ‘sunk cost bias’ for continued support of the Iraqi government, alongside humanitarian concerns about genocide and violence against civilians. Andrew Mumford suggests that the Obama administration’s overriding policy was to avoid a large-scale conventional-force response. This explains why a low-cost proxy intervention may have appealed to US policymakers.[53]

For the Iranian government, the strategic stakes were far higher. Following a general trajectory of expanding influence beginning with the 1979 Revolution, Iran became dominant in Iraqi politics once US troops withdrew in 2010. Iran was close to consolidating power commensurate with that of a regional hegemon. The 2011 Arab Spring protests, however, threatened the vulnerable position of the Iranian-aligned Assad regime in Syria. If Assad were to be ousted, Iran’s ability to influence events in Lebanon and, indeed, to leverage its proxy, Lebanese Hezbollah, to pressure Israel, would dissipate. The potential for ISIS to spawn a new Shi’a–Sunni sectarian war in and around Baghdad in Iraq also threatened these Iranian interests. A sectarian war might fatally undermine Iraq’s Maliki regime and potentially lead to masses of Shi’a refugees fleeing to Iran. The potential for such setbacks was inimical to Tehran’s national security interests and prompted the creation of significant Iranian proxy commitments across the Levant.

Iranian influence across the region presented a threat to Saudi Arabia and like-minded Sunni partners. A ‘Shi’a crescent’ from central Afghanistan to the Mediterranean loomed. Riyadh had long contested Tehran’s influence in the Middle East, in what Dilip Hiro describes as a ‘Cold War in the Islamic World’.[54] Through longstanding organisations such as the Muslim Brotherhood, fellow travellers in Sunni Islam could be found across the region, which rose to exploit the turmoil of the Arab Spring. Extant groups, such as the Syrian arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, were at an advantage in competing for influence compared to emergent elements such as the Free Syrian Army (FSA), the Syrian National Council (SNC) and the Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC).[55]

Humanitarian aid from the Gulf states, channelled through the Muslim Brotherhood into Syria, initially amounted to US$1 million to US$2 million per month.[56] In response, a veritable explosion in proxy relationships occurred with up to 300 groups reportedly present in Syria during its civil war. In simple terms, ‘Saudi Arabia sponsored Salafists while the United Arab Emirates supported secular liberals … Turkey and Qatar supported groups with a Muslim Brotherhood orientation’.[57] A new proxy relationship on one side presented itself as a threat to the other, requiring the generation of a counter-relationship to neutralise the perceived risk. These competing interests manifested akin to Newton’s third law—‘Every action has an equal and opposite reaction’. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) observed of this milieu:

The global geo-strategic position of the Middle East is the key to understanding why the Middle East matters. For millennia, it has been at the cross-roads between the civilisations, languages and cultures of north Africa and Asia, Europe and Africa, eastern Europe and Asia Minor, with Egypt, the Ottomans and Persia as key players. They remain so.[58]

Australian Interests

From an Australian perspective, the globalised nature of the ISIS threat metastasised into a range of challenges, spanning deep, close and rear geography—similar to the view of Secretary Carter. In the ‘deep’, the challenge posed by ISIS was complicated by the backdrop of the aforementioned competitions. Such competition was not limited to the Levant. In Libya, Sunni groups backed by Turkey and Qatar (which were generally supportive of Muslim Brotherhood-aligned ideology) competed with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States (which generally supported Salafi ideology, moderate groups, and/or autocratic regimes).[59]

Similar competing interests for patrons of proxy warfare had emerged with the rise of ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K or IS-KP) in Afghanistan. Australian strategic interests in that country resulted in a long-term commitment of assistance to the government of Afghanistan. In 2015, this manifested as the capacity-building mission Operation Highroad (2015–2021). This military framework had the potential to position the Australian Government to take a strong anti-ISIS-K stance across the Middle East region. Indeed, Australia had already signalled its abhorrence of ISIS to the international community, and this was an opportunity to pressure the ISIS franchise in Afghanistan with an operational commitment. However, there is little available evidence that Australia viewed the Islamic State threat as having regional implications in Afghanistan. The reasons remain opaque.

In the ‘close’ (or regional) environment, the emergence of ISIS’s affiliation with the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in the Philippines had the potential to fuel a resurgence in Jemaah Islamiyah and terrorist violence across the Indonesian archipelago. That this situation could emerge so soon after the cessation of the US-led Operation Enduring Freedom–Philippines (2002–2015) highlights the tenacity of some non-state armed groups. In response, Australia committed to a military operation in support of the Armed Forces of the Philippines in its efforts to clear Islamic State fighters out of Marawi. Regrettably, there is little material in the public domain concerning Operation Augury-Philippines (2017–2019), the ADF’s military contribution in the Philippines to this ISIS-inspired threat.[60] Again, events imply the perception of misunderstanding of the Islamic State’s globalised networked posture.

While Australia’s strategic commitment to countering ISIS remained equivocal, the regional threat posed by the group’s rise continued to grow exponentially. Analysis by the Soufan Center (see Table 2.1) suggests a greater than fourfold increase in recruitment to ASG and other extremist organisations following the emergence of ISIS in the Middle East.[61] With this context, the absence of a clear connection between Operation Augury-Philippines and Operation Okra suggests a misunderstanding among Australian policymakers of the global linkages of IS ideology.

| 2000–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | 2016–2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrests | 244 | 240 | 397 | 1,250 |

The domestic or ‘rear’ challenge posed by ISIS was ultimately recognised by Australia in January 2015 in the Review of Australia’s Counter-Terrorism Machinery.[63] This report linked offshore actions to potential domestic consequences and drew attention to the regional ‘spillover’ effects of the ISIS phenomenon, including the threat posed by lone-actor attacks and foreign fighters. The relevance of this link to the ADF was explicitly noted:

While ADF operations overseas have not traditionally been framed as part of Australia’s CT [Counter-Terrorism] mission, they have contained significant CT elements … Consequently, ADF requirements for intelligence for Operation Okra significantly overlap with everyday CT work done by Australian national security agencies … ADF missions may also provide valuable intelligence on CT issues and developments, and this needs to be factored into CT prioritisation and coordination measures.[64]

This statement clearly recognised the interconnected nature of contemporary conflict in the information age. The challenge remained, however, for Australia to coherently address the threat of terrorism across geographic regions.

Situating Operation Okra

Western militaries subscribe to the doctrine of manoeuvre warfare, which seeks to ‘collapse the enemy’s cohesion and effectiveness through a series of rapid, violent, and unexpected actions that create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope’.[65] Two cases come to mind demonstrating this ideal in practice: the Islamic State’s advance on Mosul in 2014 and the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) advance on Damascus a decade later in 2024. Theoretically, such language subscribes to a strategy of ‘annihilation’.[66]

In practice, Western forces struggle to achieve this ideal and often resort to the employment of attrition tactics.[67] A sequential, attritional approach, leveraging the technological and firepower advantages of the West, was always going to inflict significant casualties upon ISIS, which could then be exploited by Iraqi government forces to inflict a military defeat. In this sense, the strategy was effective. Questions should be asked, however, about whether the notions of manoeuvre warfare were achieved, or if the strategy might have been executed more efficiently—in terms of time, military resources, and funding.

Choosing a strategy of attrition (through the application of limited ends and means) might be entirely appropriate in an environment of strategic competition. Alternatively, an absence of action might provide space for competitors to further their strategic aims. Equally, decisive action might lead to opportunities for competitors to seize upon our military successes to secure political victories, as General Suleimani achieved at Amerli (discussed subsequently).

In the context of global competition, contemporary conflicts require a long-term, cumulative view.[68] Such nuance is arguably missing from a Western doctrinal approach that advocates annihilation without elaborating upon suitable contexts in which an attrition-based approach might be an appropriate strategy. The ongoing presence of the Islamic State, continuing political turmoil in Baghdad, unresolved questions of north-eastern Syrian sovereignty, the rising influence of Iran, and issues around foreign fighter radicalisation are second- and third-order effects of an attritionist strategy that must inform our choice of approach. In other words, consideration of such issues informs the measures of effectiveness by which the appropriateness of our strategic decisions will be measured.

As the ADF pivots towards an era of major power competition, it is intriguing that we are not looking more closely at the lessons of this past decade of competition—between the US and Russia, Sunni and Shi’a, Qatar and the Gulf States, and Turkey and Russia. These recent examples of competition demonstrate that vertical escalation carries the cost of unpredictable conflict that states wish to avoid. This is most evident in the extensive efforts taken by Russia and the US to deconflict airspace within Syria. Competition between states manifests instead in proxy wars, where patrons support irregular or non-state actors to further their strategic interests. This is a reality that is seemingly yet to be recognised within Australian policy.

By illuminating the connectivity and complexity inherent in the ISIS challenge, this chapter has provided a foundation for the paper’s further analysis. It has described the international context within which Operation Okra was conducted and identified gaps in Australia’s strategic and policy responses to the ISIS threat. Building on this context, the next chapter will propose a model for understanding the nature of irregular warfare that can aid policy and military decision-makers to better understand how ISIS was able to achieve its rapid growth and military successes.

Understanding the Enemy

In this chapter, the operations of ISIS are examined to shed light on its genesis and methods. The importance of this chapter lies in its efforts to dispel the derisive ‘terrorist’ and ‘religious’ labels, recognising instead that this group pursued strategies more akin to Communist revolutionary warfare theory. Such analysis adds nuance to our understanding of ISIS and informs the paper’s assessment of the strategies that were employed during the US’s OIR and Australia’s Operation Okra.

The Roots of Rebellion in North-Eastern Syria.

The north-eastern Syrian provinces of Deir ez-Zour, Raqqa and al-Hasakah are known as the breadbasket of Syria. However, a drought that lasted in this region from 2000 to 2010 led to significant economic deprivation, reducing approximately two to three million of Syria’s 10 million rural inhabitants to extreme poverty.[69] The drought crippled the already fragile agricultural base of this region and prompted a rural–urban migration.

In response, the Assad regime applied selective welfare on a sectarian basis. The result was that the Sunni Arab and Kurdish peoples of the north-east (comprising 58 per cent of the Syrian population) became poor.[70] Despite the wealth emanating from oil wells in this region, infrastructure was aging and there was little to no internet penetration.[71] Well-established smuggling and criminal networks between Turkey, Syria and Iraq traded in oil and antiquities and extorted the business class, decreasing businesses’ profit margins.[72]

Migration offered no reprieve for the rural poor as it overloaded a system already supporting a quarter of a million Palestinians and approximately 100,000 Iraqis who had fled the Iraq war (2003–2010). Approximately 18.2 per cent of the Syrian population had fallen below the poverty line, ‘with rural Damascus, Idlib, Homs, Dara’a, al-Sweida, and Hama governorates among the most affected’.[73]

This disaffected population of Syrian farmers offered fertile ground for ISIS. ISIS’s organisation of Syrian agriculturalists built upon a robust underground infiltration network into Iraq that had operated during the mid-2000s.[74] These local smuggling networks had served to support AQI in 2006–07 and now provided the underground function for the ISIS insurgency in the region during the 2012–13 period.[75] With increased oil supply, lower taxation and high oil prices, smuggling flourished under ISIS, resourcing the proto-state with zakat taxation income in a symbiotic relationship.[76]

The Implications of Syrian Deprivations

The competition for control over Syria’s Sunni Arab population has roots in the Alawite repression of the 1979–1982 uprisings against the Hafiz al-Assad regime, in which turmoil spread to almost all Syrian cities. This systematic and violent repression of the Muslim Brotherhood included state-sanctioned massacres.[77] Al-Qaeda strategist Abu Mus’ab al-Suri concluded from this experience that rebellion without popular support structures was hopeless against such organised repression.[78]

The Sinjar Records (a set of captured personnel records from AQI covering the period August 2006 to August 2007) show that more than half of the Syrian AQI fighters came from the north-east, most from Deir ez Zour (34 per cent) and Hasakah (6 per cent) provinces.[79] Syrian fighters also constituted 8.2 per cent of AQI recruits over this 12-month period, making it the third-highest nation represented.

The depth of the relative deprivation felt by the Sunni populations of eastern Syria produced a generation of organised resistance to authority, most pointedly demonstrated in the 1979–82 uprising. However, Nate Rosenblat and David Kilcullen argue that the chaos of the 2011 Syrian Revolution did not alleviate the deprivation felt in Raqqa, which set conditions for ISIS to present their narrative for effective governance.[80] ISIS began to infiltrate Raqqa’s governance structures in 2013, using assassination, intimidation and a ‘spiral of silence’.

Approximately 60,000 ISIS fighters controlled the 8 million inhabitants of north-eastern Syria and north-western Iraq in 2015, an area approximately the size of Great Britain. Given that ISIS represented only 0.75 per cent of the population, this level of control suggests that they were able to leverage a largely sympathetic population to establish governance functions and repress dissent.

Islamic State’s Strategy, Aims and Objectives

It has been claimed that ISIS’s strategy broadly conformed to an almost prophetic al-Qaeda ‘master plan’ authored by Sayf al-Adl, al-Qaeda’s security chief, in 2001.[81] This view is oversimplified, as al-Qaeda and ISIS (including the earlier manifestation of AQI) experienced significant friction around their differing objectives and methods. Nonetheless, ISIS did grow from al-Qaeda roots and can therefore be seen as having adopted advice from influential jihadist mentors.

ISIS exhibited strong agency in selecting its objectives and executing its strategy. Fawaz Gerges makes an interesting point in this regard, noting that ‘the two previous jihadist waves of the 1970s–1990s had leaders from the social elite, supported by ‘middle-class and lower-middle-class university graduates’.[82] In contrast, ISIS’s cadre was rural and agrarian, an echo of Mao’s strategic pivot from Leninist doctrine to his focus on the rural peasantry. In this context, evidence of ISIS’s assimilation of ‘Communist Revolutionary Warfare’ doctrine suggests a purposeful approach to the formulation of strategy.[83]

Sayf al-Adl’s strategic plan prescribed four stages from 2000 to 2013, which maps well to the actions of AQI, until its defeat in 2010. The fifth stage in his strategy, that of declaring a caliphate in Syria between 2013 and 2016, demonstrated astute analysis.[84] He recognised that Syria was weak under the Assad regime as it would be unlikely to receive American support. Syria’s Sunni majority continued to chafe under Allawite rule, and the Muslim Brotherhood networks there could be leveraged to organise an insurgency. Al-Adl’s logic was thus appropriated by Islamic State in 2014.

The nascent caliphate’s use of terrorism was part of a deliberate effort to deter Western intervention. Sayf al-Adl’s master plan asserted that terrorism could ‘make them think a thousand times before attacking Muslims’.[85] This work was published in 2004, likely influenced by the successful coercion applied by AQI to the Spanish in the wake of the March 2004 Madrid train bombings.[86] Viewed in this context, attacks by ISIS in Europe during the period 2014–2016 may have been intended to deter or fragment the Western coalition. This nuanced interpretation is generally absent from many analyses of ISIS, which are dominated by a nihilist view of such terror tactics.[87] ISIS’s efforts at deterrence, however, proved to have been ineffective.

ISIS sought to expand by creating a front organisation in Syria that could exploit the chaos of the civil war behind the façade of a grassroots militia. Abu Muhammad al-Jolani was dispatched in August 2011 to raise Jabhat al-Nusra.[88] Al-Jolani established cooperative relationships with other militants, emulating the moderate approach of united front tactics characteristic of Maoist Phase 1. Indeed, even the group’s name was evocative of this intention: Jabhat al-Nusra translates to ‘Support Front’ or ‘Victory Front’, terminology that is evocative of adherence to Maoist Phase 1 concepts.[89] Al-Jolani himself confirmed Jabhat al-Nusra’s origins within ISIS in April 2013 when he affiliated the group with al-Qaeda. Of note is that Jabhat al-Nusra and al-Jolani went on to form HTS, the de facto rulers of Syria following their success in December 2024.

By July 2013, Iraq had sunk into sectarian civil war.[90] It was fragile, weakened by ISIS subversion. By comparison, ISIS had consolidated control over eastern Syria and was poised to expand.

In sum, ISIS displayed a mature and evidence-based approach to orchestrating strategy that, while ultimately unsuccessful, had close parallels to ‘Communist Revolutionary Warfare’ doctrine for the effective conduct of insurgency. Its strategy of the rational pursuit of power over Sunni territories was wrapped in Salafi-jihadist robes that served to mobilise fighters to its cause, while distorting the understanding of its nature in the minds of Western military planners.

Islamic State’s Oxygen—Popular Grievances

Analysis of the emergence of ISIS has commonly recognised the disaffection of the Sunnis of Iraq. In Syria, the primary reason offered by interviewed fighters for joining the Free Syrian Army was ‘to take revenge against Assad’s forces’.[91] ISIS was able to derail the Arab Spring uprisings in certain areas by offering an Islamic identity that could compete against hated corrupt autocrats.[92] They thus offered a pathway for vengeance.

The Organisation of Islamic State

The organisation of violence is challenging.[93] Clandestine groups need to be secure but must accept new recruits, train, and support them, and coordinate their violent activities towards a specified political end. These tasks present what Jacob Shapiro termed ‘the terrorist’s dilemma’ as groups seek to strike an effective balance between control and security.[94] ISIS, and its earlier AQI organisation, were both aided by a strong core of former army and police officers experienced in clandestine organisations, estimated to be as much as 30 per cent of their personnel.[95]

Foundations in AQI

ISIS did not start with a blank slate. The organisation inherited from AQI a clandestine structure that was adapted with the benefit of reflection upon AQI’s failures of 2004–2007. Such lessons recognised the bureaucratic challenge of the ‘terrorist’s dilemma’, noting that bureaucratic AQI emirs were ‘more concerned with protecting their own human and material resources than distributing people and funds where they were needed’.[96] As AQI evolved into the ISI, the challenge of relying upon mercenary smugglers echoed al-Suri’s lessons from the failed Muslim Brotherhood uprising in Hama.[97] The organisation needed to be less reliant upon external parties and well integrated with the local population.[98]

Subversive Organisation

The foundation for the seizure of Mosul in 2014, and ISIS expansion in general, lies in the clandestine origins of the organisation. The Western focus on ISIS blitzkrieg tactics emanating from Syria is over-emphasised. By 2011, the AQI fighters in and around Mosul had been reduced to no more than 1,000.[99] By regressing from an insurgency to an underground ‘mafia-like’ organisation, it was able to raise money, ‘gather intelligence and spread propaganda’.[100] Verini quotes an interview with a family of Mosul court clerks reinforcing this view:

Jihadis infiltrated the criminal justice system, winning over lawyers and judges through religious appeals, intimidation, and bribery … Eventually all levels of the government were co-opted … ISI became a shadow government.[101]

The organisation thrived around Mosul City, and over time inserted operatives (or cadres) who were able to map local physical and human geography and develop nuanced localised tactics to exploit localised situations.[102] Termed ‘Operation Soldiers’ Harvest’, a prolonged campaign of intimidation and assassinations preceded and then complemented the ISIS assault of mid-2014.[103] Such tactics gave the semblance of a local popular uprising against Iraqi soldiers in conjunction with the ISIS external military assault.[104]

This underground organisation became a ‘skeleton’ to which the broader organisations could quickly adhere when transitioning from shadow governance to actual governance, while retaining roots within its localised conditions. These localised forces, known as the ‘Army of the Provinces’ or walis, retained their ties to local governance and continued to exist as guerrilla units and sleeper cells.[105] Johnston et al. give a technical description of this structure as an ‘M-form’ (multidivisional form) hierarchy in which ‘central management structure with functional bureaus is replicated at multiple lower geographic levels’.[106]

Systems of Governance

Islamic State’s administration grew from such shadow governance foundations. Diwans, or departments, which spanned education, health, precious resources, agriculture and defence, collectively demonstrated a level of organisation commensurate with that of a nation-state.[107] These systems of governance created micro-financial foundations through local taxation that were almost impervious to external disruption or interdiction. For example, ISIS was reportedly taxing (through racketeering) Mosulawis prior to Mosul’s seizure, at a rate of approximately US$8 million per month.[108] To place such figures in context, Miranova found that approximately US$230 per week was required for a Syrian group of 10 fighters to survive. This suggests that US$8 million per month could theoretically support up to 85,000 lightly armed local fighters.[109] Islamic State acquired further funding resources as it captured territory (including appropriated properties) and other assets that could be rented or sold to its members. Stable funding structures minimise looting and ‘shake-downs’ of local civilians, both of which fuel new grievances that undermine organisational governance objectives.[110]

Allegiance and Fragmentation

As organisations expand (particularly through the incorporation of existing parochial groups), this circumstance creates a countervailing risk of fragmentation. Territorial expansion may make it difficult to incorporate local groups while holding to a common ideology or objective, as was the case with the expansion of the Free Syrian Army (FSA).[111] Indeed, the factional divide between Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra, and its subsequent mergers, led to the creation of HTS. This challenge of allegiance and fragmentation influences the organisation’s ability to direct subordinates in a consistent manner, making a controlling or directive patron-client relationship more likely.[112]

The concepts of fragmentation and unification are closely related within the framework of organisational processes.[113] Rebel organisations will seek to create a ‘minimum winning coalition’ that possesses ‘enough aggregate power to win the conflict, but with as few partners as possible so that the group can maximise its share of post-war political control’.[114] To respond to this organisational challenge, ISIS went to great lengths to indoctrinate the rank and file in a highly bureaucratic manner.[115] Its objectives were to better control the newly absorbed factions and foreign fighters within their ranks, knowing that such indoctrination reduces the risk of factional splits and infighting within the organisation.[116]

Islamic State’s Competition for Control Over Sunni Populations

At first, they were nice with the people. They never asked to grow beards or not to smoke. But then they changed.[117]

During the period 2014–2018, ISIS conducted an effective campaign of control over six to eight million Sunnis in western Iraq and eastern Syria. This was effected by means of an initial intimidation campaign against opposing leaders, through a coercive form of governance over the population, and by a ‘complicit surround’ dynamic where individuals complied with what they perceived to be the majority view.

The dilemma faced by ISIS was that its ideological narrative became too effective. It had recruited Takfiri extremists who interpreted Shari’a law too literally for the cultural norms of Syrian society. Such extreme interpretation and enforcement of Shari’a disenfranchised local populations and created grievances against ISIS that it could not afford. Indeed, this situation ‘triggered a spiral of confrontation: the more ISIS increased its terror within the organisation, the more people became disillusioned and accused them of being non-Islamic’.[118]

Individuals who constituted a potential threat to ISIS power were targeted during the early stages of its campaigns to dominate an area. In Iraq, the killing of tribal sheikhs and Sahwa members claimed 2,313 members over several years.[119] The intent of such violence was intimidation—particularly to prevent a recurrent Sahwa or ‘Awakening’ from the Sunni populations of Anbar. The logic behind the violence was more than simply terrorism; it was to attrit or ‘nikayah’—to eliminate all centres of possible resistance.[120]

ISIS’s Coercive Governance

In the previous section, weight was given to the importance of organisation as it manifests in the rebel group’s own governance frameworks. In this section, we examine governance as it applies to the society the group wishes to control. This form of governance is coercive; it seeks to enforce compliance over the local population by controlling the flow of information and encouraging internal intelligence agents to denounce civilians.[121]

ISIS was able to expand by building upon the strong base of governance it had gained from its AQI roots. As it seized assets (such as oil fields or banks), the structures were already in place to prevent looting, to extract resources and channel them towards providing governance over the local population. In this context, services such as garbage collection might be prioritised to demonstrate effective government services to local populations. Even moderate governance demands organisational attention; approximately 18 per cent of the Islamic State’s personnel were assigned to governance roles.[122]

The presence of governance functions within civil society, however, should not be misunderstood as constituting effective governance. Reports were rife of mismanagement in ISIS-controlled areas.[123] The most complex aspect of governance for an organisation to achieve is the inclusion of welfare services for those under its control. It seems ISIS did not fully recognise the utility of ‘welfare as warfare’ as developed by Ansar al-Sharia, Hezbollah and Hamas.[124] To an extent, coalition military operations against ISIS disrupted focus away from governance services. In this sense, military pressure dampened a return to ‘normal’ economic activity and hence undermined the ISIS narrative of its competence in managing the governance of the Caliphate.[125]

How Islamic State Fights

The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify—by Allah’s permission—until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.

Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi.

Despite the identification of the Islamic State as the primary adversary for troops deployed on OIR and Operation Okra, beyond academic circles surprisingly little has been published about how it fought. This matters as the Western response to ISIS logically needs to address the strategy ISIS employs. This section maps the tactical application of ISIS strategy and forms the analytical basis on which Western interventions can be assessed.

ISIS narratives of a deliberate and progressive plan to establish the caliphate supported its strategy. The seminal work by Michael Ryan in 2013 titled Decoding Al-Qaeda’s Strategy presented the argument that al-Qaeda strategists subscribe to classic irregular warfare theory, which they termed ‘Revolutionary Guerrilla Warfare’.[126] This term refers to Maoist strategy, which evolved and was improved upon by General Giap in Indochina. Giap advocated a three-phase strategy: contention (involving infiltration, political subversion, and terror actions); equilibrium (involving guerrilla warfare, establishment of base camps and logistics caches); and the counter-offensive (involving mobile warfare to consolidate control).[127] In this context, George Tanham of the RAND Corporation observed that:

In both the strategic and tactical areas, it [this three-phase strategy] offered the Communists the greatest potential gain at the least possible risk. The initial low level of violence tended to preclude Western intervention, and at the same time involved the least risk of any possible loss of prestige for the Communists. It also enabled the Vietminh to pose as leaders of the insurgent nationalist movement and to gain popular support, while behind the scenes consolidating their power, which led to eventual control.[128]

Tanham’s analysis echoes Ryan’s presentation of al-Qaeda (and subsequently ISIS) as having orchestrated strategy based on its historical analysis of warfare, employing selective terrorist tactics to achieve specific effects.[129] Similarly, contemporary Salafist-jihadist strategy has learned from irregular warfare history. Indeed, in Abu Mus’ab al-Suri’s analysis of the failed Syrian uprising of 1979–1982, he strongly advocated that al-Qaeda emulate lessons from Communist revolutionary warfare theory.[130]

Al-Qaeda strategist Abd al-Aziz al-Muqrin assumed command of al-Qaeda’s Saudi Arabian insurgency efforts until his death in 2004. Muqrin’s legacy is a manual of military doctrine, Dawrah al-Tanfidh Wa Harb al-‘Asabat (A Practical Course for Guerrilla War), which advances a similar three-phase model, using the language articulated below:[131]

- attrition (strategic defence)

- relative strategic equilibrium (a policy of 1,000 cuts)

- military decision (final attack).

Another al-Qaeda strategist, Abu Bakr Naji, in The Management of Savagery, translated such guerrilla warfare theory for an Islamist context. Specifically, he captured the dynamic of polarising politics that can destroy social cohesion, particularly where ‘the catalyst is terrorism’.[132] Doctrinally, emphasising the employment of terror as a tactic conforms with Maoist Phase 1 subversion. During the initial stages of an insurgency, terrorism conforms with the perverted Bolshevik logic of the ‘heightening of contradictions’: when violence is perpetrated against civilians, the government is blamed for its inability to protect them, and inevitable government overreactions result from such violence.[133]

Once US forces had withdrawn from Iraq in 2010, the nascent ISIS began to apply such lessons from its AQI roots, employing a strategy that invoked Maoist teachings.[134] While remaining responsive to the social and political conditions within certain wilayats (provinces), its strategy was evocative of Giap’s micro-application of nuanced progression through the Maoist three phases.[135]

Professor Craig Whiteside explicitly concludes that ISIS’s strategy for seizing control over a target population is fundamentally the application of classic insurgency doctrine.[136] This application of an essentially Maoist insurgent strategy has been clearly explained by Aaron Zelin.[137] Zelin’s recognition of the Islamic State model, using the case of Wilayat Tarabulus in Libya, is worth quoting at length for its continuity with the strategy of revolutionary guerrilla warfare:

In the first phase of gaining control over a given area—the intelligence phase—ISIS is involved in the establishment of sleeper cells, the infiltration of other groups, and the creation of front groups … Sometimes simultaneously with the intelligence phase, other times after it, ISIS begins to operate militarily in the specific area where it is attempting to gain influence … ISIS employs asymmetric warfare, with tactics that include hit and run attacks, sniper assassination operations, drive-by shootings, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), car bombs, and suicide attacks …

The beginning of control over small pieces of territory, usually villages or neighbourhoods in larger cities, provides IS with the opportunity to commence its dawa program, in which ISIS members start reaching out to the local population … Beyond dawa, once ISIS has partial territorial control, it also begins its hisba activities... [to] make sure residents are praying on time, attending prayers, and closing their shops … The final phase preceding full territorial takeover is the start of basic governance. This primarily involves the introduction of taxes and exertion of its judicial powers …

Once ISIS has been able to gain full territorial control over a particular area … the intelligence apparatus also strives to ensure former officials and other insurgents repent and give up their weapons, and it provides a stopgap against potential fighters (especially foreigners) defecting or fleeing its territory. It helps with the suppression of potential awakening-type uprisings against ISIS.[138]

The logic of violence can be hidden by the simplistic language of ‘terrorism’ or ‘terrorist groups’. The abhorrent nature of violence directed toward civilians or ‘asymmetrically’ against military forces using improvised explosive devices (IEDs), suicide bombers or rockets confuses analysis. Using the Global Terrorism Database, the frequency, magnitude and nature of ISIS-inflicted casualties consistently demonstrates that, prior to the seizure of key cities, there is a phase of violence (generally conforming to Maoist Phase 1) of subversion, assassination, terrorism and intimidation.[139]

Where violence seems to have conformed to a Maoist strategic logic, the ISIS movement has generally been more effective. Where it has not, the movement has been less successful.

ISIS strategy demonstrated a correlation between violence and propaganda. In the seizure of Mosul, ISIS claimed that its spies were everywhere in the city and that Iraqi officials ‘would never know whether the soldiers on either side of them were loyal’.[140] Such a message resonated following almost five years of ISIS racketeering, assassinations and intimidation in Mosul, and a campaign of violence waged from June to September 2013 in and around the city. The message was therefore believable and overcame the manpower disadvantage of ISIS forces that made the Mosul campaign extraordinary: Approximately 1,300 men against the nominally 60,000-strong Iraqi Army, federal and local police defied conventional military logic .[141] Joby Warrick explains this operation well:

The city’s [Mosul’s] remaining defenders were ill-supplied, since much of the defenders’ armour and heavy weapons had been ordered to the south, to help retake Ramadi and other Anbar Province towns during the January fighting … On cue, ISIS cells based inside the city also opened up with grenades and sniper fire … within hours, columns of ISIS trucks had advanced to within a few blocks of the Mosul Hotel, where [General] Gharawi had set up his command center. At 4:30 p.m. came the decisive blow. A large water truck packed with explosives barrelled into the hotel, exploding in flames and killing or injuring many of the Iraqi force’s senior officers … The rest of the army’s defences collapsed soon after that … they seized control of Mosul’s main prison, releasing the Sunni inmates and summarily executing the others.[142]

The terror that followed the clear Phase 2 prosecution of guerrilla targets further reinforced this narrative. Punishing those who resisted (or were perceived to have resisted) helped ISIS to establish control over the local population in Mosul.

This ‘Maoist’ style pattern of violence is also evident in Syria. Prior to 8 April 2013, Jabhat al-Nusra (al-Nusra Front) was supposedly acting on behalf of Islamic State interests in Syria. The use of ‘front’ organisations further demonstrates Islamic State’s absorption of Maoist insurgency doctrine. Similarly to ISIS’s strategy in Mosul, Jabhat al-Nusra’s tactics included:

the gradual infiltration of villages and towns; the mapping of social, regional, and tribal groups (heads of clans, influential personalities, businessmen, activists, clerics, and dissidents); and Islamist indoctrination camouflaged as the opening of al-Dawa (the call to religion) offices.[143]

Following the public split of Jabhat al-Nusra from ISIS on 8 April 2013, the pattern of ISIS violence conforms to the progressive Maoist model in transitioning from Phase 1 subversion to Phase 2 guerrilla warfare from September to October 2012. In this phase, military competition dominates the frequency of observed violence, with a secondary focus towards control of local populations. To control local populations, ISIS disarmed them (to establish a monopoly of violence) while concurrently protecting such communities from criminal exploitation in the form of checkpoint extortion whenever they could.[144] A clear campaign of violence from June to August 2014 expanded ISIS’s area of control to all of Raqqa province by 24 August 2014. Following ISIS’s loss at Kobani in January 2015, a further campaign commenced in February 2015, culminating in the seizure of Palmyra in May 2015.

Summary

In 2010, the earlier incarnation of ISIS, AQI, was effectively defeated militarily with the killing of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri (who was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s immediate successor and the ISI’s minister for war).[145] Despite this defeat, AQI and then ISIS, have ‘remained’. The conditions from which insurgency grows evidently remained unaffected. The Levant has a population of 80 million, of which approximately 53 per cent are under 25 years old—a youth bulge that provides no shortage of disaffected young males, frustrated by a lack of opportunities.[146] These underlying social tensions have fuelled the growth of ISIS from its AQI roots—without addressing such tensions, there is a high likelihood of renewed emergence of ‘ISIS 2.0’ from seeds of discontent that remain in Iraq and Syria.

This chapter has focused on ISIS to understand the logic of violence it employs. In so doing, it has rejected the label ‘terrorist organisation’ as being an inadequate and counterproductive analytical basis on which to develop robust strategic counters. It is true that the concept of terrorism provided a strategic logic to support propagandising, intimidation and subversion, particularly during the initial stages of ISIS expansion. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of terrorism as a tool declined as governance obligations emerged. The fact that ISIS conformed with Maoist-style insurgency strategy or ‘Communist Revolutionary Warfare’ doctrine is an insight absent from Western responses to the ISIS threat.

Strategic Assessment

In this chapter, I extend the analysis of how ISIS fights to examine the counter-strategy adopted by the Operation Okra intervention. The power imbalance in favour of the US against ISIS meant that achieving military defeat through a concerted, deliberate Western campaign of attrition was a foregone conclusion. However, an examination of the performance of this is necessary to determine if the outcome could have been achieved more efficiently. Were military actions relevant to the political objectives intended? This question is vague but also points towards the inherent wisdom in the Obama Administration’s choice of a proxy strategy to limit its involvement. Assessing the efficacy of this choice, particularly in light of the complexities outlined above, will be relevant to Australia in any preparation for future conflicts of a similar nature.

This chapter examines the strategic guidance afforded to the Operation Okra intervention. How did the ADF approach its strategic relationships in a conflict setting? What can be derived from Australian and US military responses? How effective were the operational lines of effort? How do these lines of effort interact?

I conclude the chapter with inferences from several hypotheses regarding the way the coalition believed it could achieve its strategic objective to defeat ISIS. I use the term ‘hypothesis’ to encapsulate planning expectations: ‘If I do x, then y effect upon ISIS will be achieved’. By framing the problem this way, planning becomes a task conducted with reference to a hypothesis, informed by the way that ISIS fights. While this may be true, military planning is arguably also informed by subcultures of Defence organisations and heuristics formed by earlier experiences.[147] By explicitly examining lines of effort as hypotheses, I aim to illuminate counterproductive reasoning that might undermine future operations. In short, I argue that across all four ‘lines of operation’ identified, there is potential for improved efficiency and efficacy when engaging non-state armed groups.

The Counter-Strategy to Defeat ISIS

Four intertwined Western hypotheses emerged as central to the strategy adopted to defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria. If they are effective, all hypotheses should function as ‘lines of operation’ that mutually reinforce the intended strategic objectives. The validity of these hypotheses will be examined in turn throughout this chapter.

Employment of Air Power Against an Irregular Adversary

What Is the Hypothesis?

Some analysts have argued that air power was critical to OIR and that constraining its employment may have extended the duration of the war. The employment of air power purportedly played a critical role in OIR.[148] Some argue that it could have played a greater role, yet the Chief of Staff of the US Air Force, General Mark Welsh, indicated that a moderated role was deliberate.[149] The role of air power against ISIS was thus orientated towards strategic cost imposition as a component of the overall proxy strategy. This accepted nuance suggests that a greater range of possibilities for the employment of air power were available to the OIR coalition.

What Evidence Suggests This Hypothesis Is Valid?

Air power was deliberately used as a type of ‘reassurance’ to compensate for the mixed quality of partner ground forces.[150] There is a sound logic to this approach in the context of a proxy strategy where advisors simply cannot be assured of the quality of their partners. Indeed, the debacle around the collapse of Mosul in June 2014 would suggest that Iraqi Army units had to be viewed as risky partners. Tactical reassurance to Iraqi partners could be provided through aerial supply drops, as was very publicly displayed in the initial Western response to the humanitarian crisis at Sinjar in 2014. The coalition’s allocation of resources to air power—which favoured reassurance in the ‘close’ fight (particularly with the provision of intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance (ISR) capabilities)—came at the cost of having platforms available for the ‘deep’ fight of aerial interdiction, counter-finance, and strikes in depth. A tension thereby emerged that is relevant to considerations raised later in this section.

The efforts of special forces to assimilate lessons from counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan were quickly applied to the Iraq context in 2014, resulting in the ‘strike cell’ concept.[151] A strike cell uses unclassified means of reporting target data into a classified coalition air coordination space—data that might facilitate air strikes in support of partner forces in real time. Strike cells represented a useful tactical adaptation for the conduct of proxy warfare, as they yet again provided a form of reassurance to partner forces. By January 2015, proxy warfare waged through Iraqi security forces supported by Western air power was generating an average of 1,000 ISIS fighters killed per month, a level of attrition that created sustained pressure upon the ISIS organisation.[152]

Several near-miss instances of Western platforms almost engaging Shi’a militia groups highlighted the challenges of ambiguous battlespace deconfliction processes and the utility of strong oversight and control.[153] The ever-present danger was that a strike against these Iraqi -government supported forces could very well reignite Iraqi sectarian civil violence—a strategic ‘sword of Damocles’.

Air power was used midway through the campaign against ISIS to target oil and other sources of finance. ‘The theory of victory … was that starving ISIS of resources would reduce its capacity to operate, thereby undermining its organisational and military strength.’[154] Counter-finance efforts purportedly reduced ISIS’s oil revenue by half, from $30 million per month to $15 million.[155]

When assessing the efficacy of such efforts, it is useful to consider both the first- and second-order effects. For example, did the regime’s reduced financial income result in increased taxes upon controlled populations, increasing the possibility of an uprising?[156] Were the civilians driving fuel trucks legitimate targets in the eyes of the local population if they were simply trying to make a living? Would a local population feel the same way about the legitimacy of financial targets that potentially included the banks that were protecting their personal savings? These questions have no easy answers. Counter-finance elements of the air campaign certainly eroded ISIS’s strength but may have created new long-term grievances among the Sunni populations of Iraq and Syria.[157]

What Evidence Suggests the Hypothesis of Air Power’s Efficacy Is Invalid?

The bombardment [on Mosul] was carried out by the government. The air strikes focused on wholly civilian neighbourhoods … The bombing hurt civilians only and demolished the generator. Now we don’t have any electricity … because of this bombardment, youngsters are joining ISIS in tens if not in hundreds because this increases hatred towards the government, which doesn’t care about us as Sunnis being killed and targeted.[158]