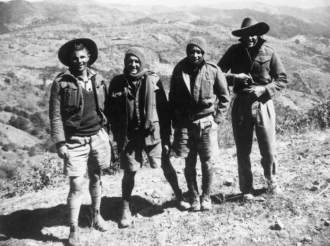

Source: Australian War Memorial (AWM); Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Australia has experienced major power competition in the Indo-Pacific before. When we last experienced this environment, we deployed forces into south-western China under the little-known Mission 204 in 1941. This mission was expressly intended to deter Japan from aggression; a purpose that still resonates today in the context of the 2023 Defence Strategic Review which establishes a need for ‘asymmetry’ against a more powerful competitor, to affect ‘a strategy of denial.’[i] Mission 204 thus highlights capacity-building lessons pertinent to the Australian Army that resonate in the contemporary environment of major power competition.

Mission 204 was raised by the British in February 1941 in response to a request for support from Chinese President, Chiang Kai-shek, to grow ten Chinese guerrilla warfare battalions that would be used against the Japanese Kwantung Army.[ii] Mission 204 envisioned a contingent of 250-300 advisers, of whom about 40 were Australian soldiers, commanded by Major D. MacDougal, drawn from the 8th Division in Malaya on 27 July 1941.[iii] This commitment was made prior to war with Japan, in other words, during competition.

Despite its support to China, the British cabinet did not wish to incite direct conflict with Japan.[iv] Accordingly, with a force of 300 Commonwealth troops, Mission 204 was directed to undertake action that would force ‘the Japanese to lock up the maximum forces.’ As such, it would ‘have as its primary object the strengthening of our defensive position on our own frontiers [i.e. Commonwealth colonies].’[v] To achieve its purpose, Mission 204 was to raise six Chinese guerrilla battalions to each of which a demolition squad of Commonwealth officers and other ranks would be attached.

From an Australian government perspective, it was believed that such quiet assistance to the Chinese would be ‘a means of absorbing Japanese energy and aggression.’[vi] Australian policy rationale can be discerned from the strategic argument made by the Australian High Commissioner in London that points toward a belief in ‘unconventional deterrence’:

The alternatives before us as I can see them are: (1) To pursue the idea of negotiating a wide settlement... (2) To abandon the idea of a wide settlement and concentrate on keeping alive and increasing Chinese resistance, and at the same time intensifying financial and economic pressure on Japan so as to deter her from outside adventures and to bring her into a more reasonable frame of mind (emphasis added).[vii]

On 10 November 1941, Australian troops began to be dispatched to China as tensions increased with Japan.[viii] Australia’s commitment to Mission 204, however, was largely overtaken by events with Japan’s 7 December 1941 commencement of hostilities.[ix] In response, some military elements of Mission 204 were quickly re-directed against Japanese targets on the Thai-Burma border.[x] During this period, pre-mission training was conducted at the Bush Warfare School, Maymyo, Burma. Ultimately, it wasn’t until 16 February 1942 that the Australian component of Mission 204 finally arrived at the Chinese Nationalist training areas, after travelling some 3360 kilometres to Ch’i-yang (Qiyang) overland from Burma.

Luck was not on the Commonwealth’s side. On 16 March 1942, the mission’s British commander, Major-General Dennys was killed in an air crash at Kunming. The mission was also beset by logistic and health problems, with some thirty-five per cent of the Australian contingent becoming non-battle casualties over the first three months. The mission had aimed to hamper the southward movement of the Japanese army using the Chinese guerrillas, a mission rendered purposeless, from a British perspective, following the fall of Singapore.

It took until 9 September 1942, before General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief India Command, cabled Britain with the recommendation that the mission be withdrawn.[xi] On 29 October, the Australian component of the mission was returned to Australia, a decision likely influenced by the medical state of the force.[xii] The Chinese Commando Groups, now termed ‘Surprise’ battalions, were retained by the Chinese Nationalists in the form of ten, 1,000-men formations under General Li Mo An.[xiii]

The dilemma that Mission 204 exposes is that of political discretion versus military effectiveness. To be effective in competition, which might deter or complicate an adversary’s considerations about escalating into conflict, some risk must be borne. To transition into being effective in conflict, an advisor force must be logistically supportable and geographically proximal to where it is needed, having built the intelligence and support networks (‘the underground’) that serve to protect and sustain the advisors. It should be tailored to what the partnered force needs, having built the skills and trust with the partnered force to be operationally employable at the time required.[xiv] Mission 204 was unlikely to have ever been tactically successful due to deficiencies in these characteristics. Importantly, however, it was able to contribute to the defence of Burma due to being forward deployed to conduct pre-mission training at the Bush Warfare School. This example illustrates that strategic flexibility can be derived from pre-conflict engagement.

Source: Unknown - Donor was Maurie Kimbell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Australian War Memorial (AWM) catalog number P00763.001

The lessons of Mission 204 are pertinent today, in the development of resistance strategy, and external ‘support to resistance’ doctrine when training aims to build up a whole-of-society capacity to resist an aggressor’s offensive military actions, as has recently been demonstrated in Ukraine.[xv] What is particularly intriguing about Mission 204 is the asymmetry inherent in a mission of only 300 Commonwealth soldiers, intended to mobilise ten battalions of Chinese Nationalist combat power, to impose costs that might prevent the use of military force elsewhere. Modern counter-insurgency maxim posits that manpower in the order of 20:1 is required by the counter-insurgency force to establish control over an area. As such, Mission 204 had the potential to divert several Divisions of Japanese combat power. Had it been more effectively executed, it may have had a significant impact on the closely fought Japanese offensives of Malaya and Burma.

Ultimately, Japan had made the decision to commit to a southern advance long before Mission 204 had begun its intended pre-conflict mission.[xvi] Nonetheless, the belief among Commonwealth policymakers that the imposition of costs might serve to deter adventurous policy is the most relevant lesson to derive from the history of when Australia last went to war in China.

This article is a submission to the Winter Series 2023 Short Writing Competition, 'Army’s Role in Train, Advise and Assist Missions'.

[i] Department of Defence, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia (2023).

[ii] Lionel Gage Wigmore, ‘Appendix 1 – Australians in Mission 204,’ in Australia in the War 1939-1945, Official History, Series 1 – Army, Volume IV – The Japanese Thrust (1st edition, 1957), p. 643; Fred C. Goode, No Surrender in Burma: Operations behind Japanese Lines – Captivity and Torture, (South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2014); Ogden, Tigers Burning Bright, 2013, p. 224. Of note is that the British Army caused no end of consternation with the Foreign Office due to concerns that British soldiers could end up fighting alongside the Chinese prior to a declaration of war between Britain and Japan; Despite this request for support from Chiang Kai-shek, the British demonstrated limited trust in their Chinese Nationalist partner and calculated action in support of British national interests. In September 1941 directing that the Chinese ‘not be informed’ of Mission 204 preparations. Interestingly, the British evoked the example of “volunteers” to Finland during the Russo-Finnish War as the example intended with Mission 204. War Office to C. in C. Far East, Desp. 88880, WO106/3555A, (9 Sep 1941); C. in C. Far East, 41239, WO106/3555A, (5 Sep 1941).

[iii] Lionel Gage Wigmore, ‘Appendix 1 – Australians in Mission 204,’ in Australia in the War 1939-1945, Official History, Series 1 – Army, Volume IV – The Japanese Thrust (1st edition, 1957), p. 643; Dr Eric Andrews, ‘Mission 204: Australian Commandos in China, 1942,’ Journal of the Australian War Memorial, No. 10, (April 1987), provides the higher number of approximately 300 advisors (36 officers and 260 other ranks), p. 12; These troops did not have specific training or expertise in guerrilla warfare.

[iv] Dr Eric Andrews, ‘Mission 204: Australian Commandos in China, 1942,’ Journal of the Australian War Memorial, No. 10, (April 1987).

[v] War Office to C. in C. Far East, 76963, WO106/3555A, (9 Jul 1941).

[vi] Andrews, ‘Mission 204,’ (April 1987), p. 11.

[vii] ‘Mr. S.M. Bruce, High Commissioner in London, to Mr. R.G. Menzies, Prime Minister,’ London, (received 7 August 1940), in W.J. Hudson & H.J.W. Stokes (eds.), Documents on Australian Foreign Policy, 1937-49: Volume IV: July 1940 – June 1941, (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1980), p. 71 (emphasis added).

[viii] Andrews, ‘Mission 204,’ (April 1987), p. 13.

[ix] A sense of the growing confrontation with Japan can be discerned from cables immediately prior to this decision being made. For example: ‘What is needed now is a deterrent to Japan of a most general and formidable character… United States policy of gaining time has been very successful so far, but our joint embargo is steadily forcing the Japanese to decision for peace or war… The Japanese plan to attack Yunnan and cut the Burma Road threatens disastrous consequences to Chiang Kai-shek. Collapse of Chinese resistance would not only be a world tragedy in itself but would free large Japanese forces to attack North and South.’ ‘Lord Cranborne, U.K. Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, to Mr. John Curtin, Prime Minister,’ London, (received 6 November 1941), in W.J. Hudson & H.J.W. Stokes (eds.), Documents on Australian Foreign Policy, 1937-49: Volume V: July 1941 – June 1942, (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1982), p. 173.

[x] Goode, No Surrender in Burma, 2014.

[xi] Andrews, ‘Mission 204,’ (April 1987), p. 18.

[xii] Andrews, ‘Mission 204,’ (April 1987).

[xiii] ‘204 Military Mission Chungking to C.in C. India,’ (21 May 1943) in Assistance to China, 22 Dec 1942-30 Dec 1943WO106/3558A.

[xiv] The British were attuned to the Chinese being unlikely to deliver on their promise to increase pressure everywhere in the event of war between Britain and Japan. For this reason, British efforts in preparing for guerrilla warfare were primarily directed toward Hong Kong. War Office to C. in C. Far East, 84745, WO106/3555A, (18 Aug 1941).

[xv] These lessons are captured in Andrew Maher, ‘Ukrainian Resistance,’ Land Power Forum, (15 Jul 2022); Will Irwin and John F. Mulholland, Jr., Support to Resistance: Strategic Purpose and Effectiveness, Joint Special Operations University, (June 2019).

[xvi] U.S. ‘MAGIC’ intercepts identify that the Japanese leadership had decided to ‘strike south’ on 4 July 1941, if not earlier. Francis Pike, Hirohito’s War: The Pacific War 1941-1945, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), p. 126.