Some thoughts on the civil-military operations in Australia’s Second World War Borneo Campaign

The Australian Army’s primary focus is warfighting, and rightly so, given the Army’s mission. However, ‘what happens after the fighting?’ This question is not one that most of us would often consider, even Royal Australian Engineer (RAE) officers such as myself. Yet perhaps we should. Even our more recent operational experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrate a general lack of consideration as to ‘what comes next?’ or ‘what happens after the fighting stops?’

Civil-military operations was the topic assigned to me during a recent Australian Army Research Centre (AARC) staff ride to what was, in 1945, British North Borneo. Initially, I was in shock. I had never studied this area and had no particular interest in it until I realised that RAE is intrinsically linked to this essential military function. Many of the tasks we undertake benefit not only the military but also civilians. Perhaps that’s why I was drawn to the Corps, one that aims to have a lasting impact on the world (insert debate on the best Corps here).

Why the Borneo Campaign?

Australia’s Borneo Campaign commenced in March 1945. By this stage, the Army was experienced, toughened, and competent. It was I Australian Corps that led the Borneo campaign. For the most part, it was well-trained and well-organised, with over six months of lead-up training in north Queensland, including comprehensive corps-level planning exercises.

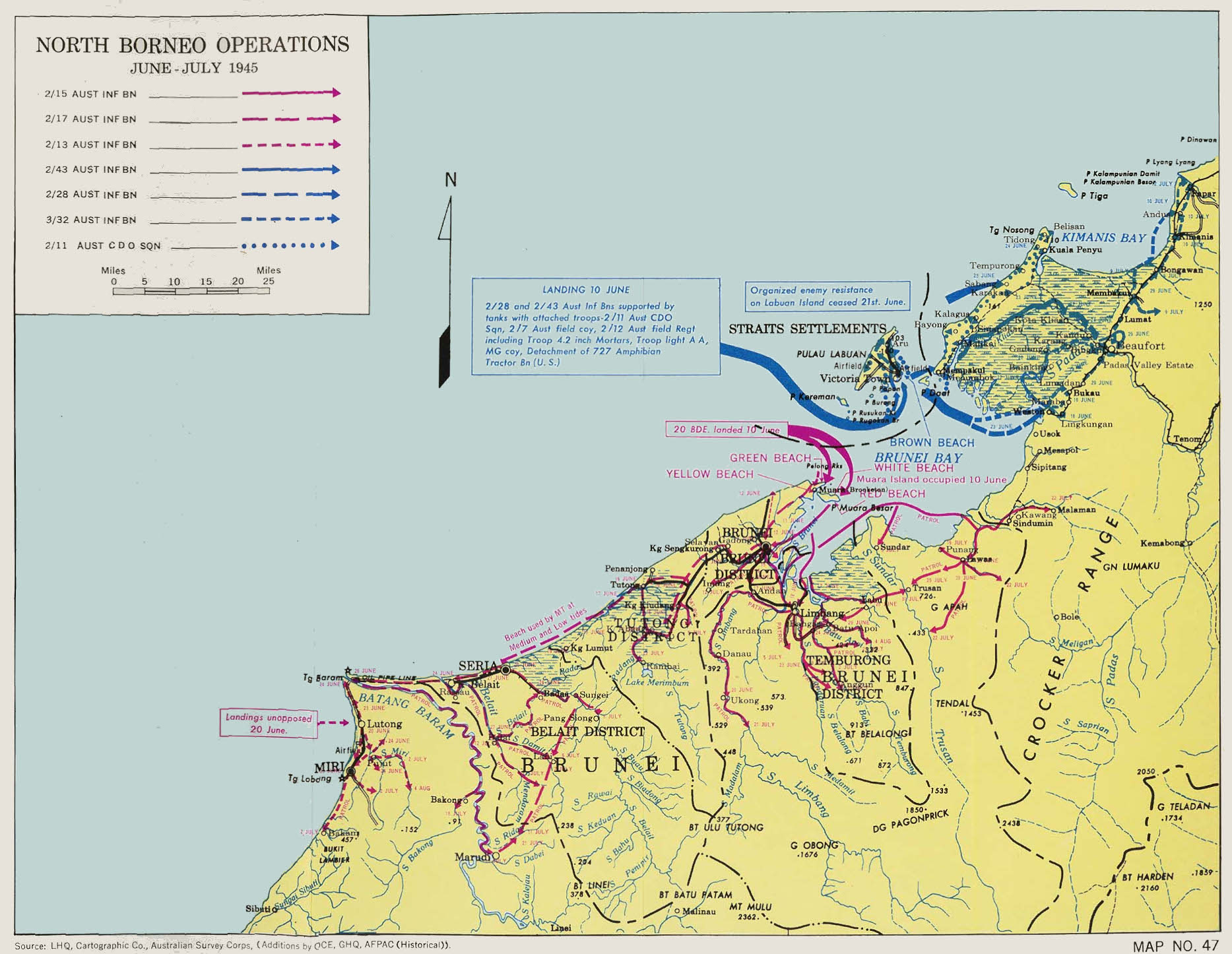

The Borneo campaign involved the most extensive and complex set of operations to be planned and executed by Australia during the Second World War, and arguably remains so to this day. It included special warfare, littoral, riverine, and civil-military operations. It also involved coordination between the Australian Army, Navy and Air Force, as well as significant naval, air, logistic and strategic support from the US.

The campaign was one of Australia’s little-known success stories. Notably, it remains particularly relevant today, given the focus of the National Defence Strategy 2024 on littoral manoeuvre, joint and combined operations, and the fact that Borneo lies within Australia’s primary area of strategic interest. This Land Power Forum post focuses on the 1945 British Borneo operation, in which approximately 29,000 allied troops were involved.

Image attribution: By Office of the Chief Engineer, General Headquarters, Army Forces Pacific, Public Domain

Image file source: Public Domain

A little bit about 1945 Borneo

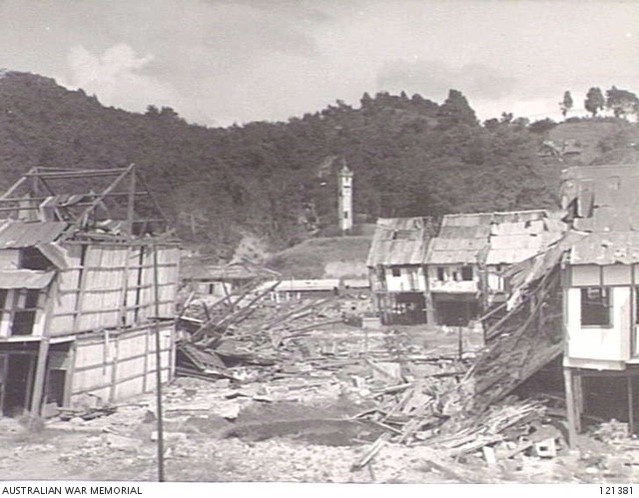

Borneo is the third-largest island in the world. The climate is warm and humid, with annual rainfall reaching up to 4.5 metres. In 1945, British Borneo had a diverse population of approximately 800,000, comprising indigenous peoples, Malays, and Chinese. Rubber, rice, sago, and coconuts were the country’s most significant crops, with rubber being the primary export and the territory’s main source of income. Additionally, oil was exported from Sarawak and Brunei, with the Seria oilfield being the largest in the British Empire. British Borneo also supplemented its rice harvest with imports generally coming from Burma and Thailand via Singapore. However, during the Japanese occupation, ordinary logistic chains were disrupted. Acute food shortages ensued, leading to widespread cases of malnutrition and disease. Furthermore, as the Japanese retreated, they destroyed crops and set fire to the oil fields. All coastal towns in British Borneo suffered extensive damage from Allied bombardment. Most remaining buildings, roads, drains, and sanitation systems had been neglected or were in disrepair.

Image source: Australian War Memorial (121381)

But you’re still asking, what happens after the fighting?

The question of ‘what happens after the fighting’ is closely linked to what occurs during it. Necessary organisational structures need to be in place to manage the aftermath, long before military operations commence. At the end of 1944, restoration of every day civilian life was accomplished relatively quickly. Australia had limited experience in civil-military affairs however, the Australian government was determined to showcase the Australian Army’s capability in this regard. In doing so, it hoped to secure post-war influence within the surrounding region. For the British Borneo campaign, Australia established the British Borneo Civil Affairs Unit (BBCAU). This unit included British and Australian members in a 1:2 ratio. However, the unit was undermanned, largely inexperienced in this field, and was not adequately sized to fulfil its mission. Consequently, it was extensively supplemented by the 9th Australian Division.

So, what happened?

The Japanese had harsh occupation policies, forced labour, limited relief measures and provided practically no medical attention to the civil population. Consequently, the occupation period in British Borneo was characterised by widespread malnutrition and a marked increase in diseases such as malaria, tropical ulcers, scabies and beriberi.

In preparation for the landings, there was significant allied bombardment, causing extensive infrastructure damage, rendering large numbers of civilians homeless. This meant that when BBCAU landed with the 9th Australian Division on 10 June 1945 at Labuan and Brunei Bay, it faced an immediate and significant humanitarian challenge that had largely been underestimated. Following the landing, relief housing was built, and within a week, 3,000 people were housed. After the allied perimeter was expanded, there was an additional influx of refugees seeking food and medical attention.

Once the fighting had died down and major population centres were largely secured, acute distress was relieved, allowing work to commence on all the other aspects of a peaceful society that were disrupted during the occupation. The police force was re-established, postal and telegraph systems were rebuilt to 80% of their pre-war capacity, and education resumed with Australian Military Education Officers filling gaps where there were no teachers. At this stage, the transition to a civilian administration began, with the handover being completed by April 1946.

Engineers were responsible for constructing airfields and bulk oil facilities, repairing ports, maintaining refrigeration systems, and overseeing main roads and drainage systems, as well as fixing sawmills, steam engines, utilities, and other essential base infrastructure. The shortage of engineers and materials for repairs made it increasingly challenging to maintain land lines of communication. In response, the local population returned to their pre-war jobs to assist with the efforts. By the end of August 1945, thousands had taken paid positions repairing and rebuilding the country. This reconstruction work was crucial, not only for resuming everyday life and regaining the trust of the local community, but also for keeping Australian troops occupied after the fighting ended. Meaningful employment was of mutual benefit and helped avert undesirable activities such as looting and substance abuse.

Image source: Australian War Memorial (109481)

Some closing thoughts…

Although some would argue that it is not military’s job to clean up after conflict, the question should rather be, ‘to what extent?’ There is a fine line between not enough and too much. Not enough, and the military risks being viewed by the civilian population as ‘just as bad’ as the adversary, potentially sowing the seeds of popular discontent. Too much, and the military risks impeding the re-establishment of government and services, allowing the population to become overly reliant on military assistance, coming to expect that it will always be there.

In the case of Borneo, I believe the balance was correct. In tangible outcomes, BBCAU alleviated acute distress, restored order and security, took initial steps towards rehabilitation, and paved the way for a smooth resumption of civil government. That being said, such an effort would not have been possible without the assistance of the 9th Division, which would not have been available if the combat had been as heavy as anticipated. The Allies’ gross underestimation of the extent of humanitarian relief that would be required in Borneo also emphasises the requirement for detailed and accurate planning for Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC). For my own part, the opportunity to engage with the local Borneo population during the Borneo Staff Ride revealed that a significant level of gratitude remains towards the Australians for their role in liberating Borneo.

But could the Australian Army achieve the same effect again in the future? Yes, with some effort, I think it could, albeit with a range of similar and different challenges. In Borneo, reinstating British colonial rule was inherently straightforward due to the commonality in beliefs and values between the respective governments. Today, Australia is more likely to be involved in efforts to reinstate an administration that does not necessarily share our country’s predominant cultural values. Therefore, we must tread carefully. Rather than reinstating an administration of our choosing, Australian efforts should focus instead on creating a bridge between conflict and peace, paving the way for a successful and sustainable post-conflict administration. As we have seen in recent times, overstaying our welcome can lead to the development of widespread discontent.

Assuming that CIMIC is regarded by the Australian government as integral to the overall success of military missions, it is worthwhile reconsidering how the Australian Army can further enable, organise and leverage its capabilities in support of post-conflict requirements. This is especially the case given growing strategic uncertainty within Australia’s region, a geographic area characterised by large civilian population centres with less developed economies than our own.

The Australian Army’s CIMIC capabilities are crucial to any 'hearts and minds' campaign, connecting military, government, non-government organisations, as well as civilian contractors and aid agencies. Beyond liaison, CIMIC also encompasses efforts to collaborate with the local government to maintain stability and to assist managing the arrival of foreign aid. Tasks particularly suited to the military include project coordination to avoid the ‘too much too soon’ problem, as seen in Afghanistan, which caused widespread corruption and profits being moved offshore due to a shortage of local civilian contractors. The Australian Army is well placed to help coordinate these efforts.

It would seem that Reservists and members of specialist units, such as the Chief Engineer Works and the 6th Engineer Support Regiment, are ideally placed to lead CIMIC efforts. Many such individuals have prior civilian experience and have a broad understanding of the nuances of the civilian operating environment. They are also adept in ‘translating military to civilian speak’. Further, Reservists have a substantial surge capacity. Having a pool of CIMIC-trained personnel, dispersed amongst different units, who can be called upon when needed, seems to be the most logical source of CIMIC capability within Australia’s relatively small Army. These assets could be supplemented by combat troops should Australia ever again be required to conduct such a momentous task as the North Borneo operation.

Ultimately, while the modern battlefield is vastly more complex than Australia faced during World War Two, one constant remains: people.