Abstract

Stabilisation and support operations such as those currently being undertaken by the Australian Defence Force as part of larger whole-of-government efforts in East Timor and the Solomon Islands present a number of challenges. For the military commanders and staff, the primary challenges lie in understanding the situation, identifying threat sources, determining courses of action and developing lines of operation through the orthodox application of doctrinal appreciation processes. The application of the Intelligence Preparation and Monitoring of the Battlefield (IPMB) and (Joint) Military Appreciation Process (J/MAP) to conventional and counterinsurgency warfare problems is well understood. However, the use of these tools is less intuitive when the area of operations encompasses a permissive but sovereign nation-state. In this situation, threats to security are latent but may emerge from interactions between a myriad of stakeholders; the mission itself, however, relates more closely to anti-insurgency or indigenous capacity-building end-states than to counterinsurgency and the neutralisation of identified threat sources. In such cases it may be beneficial to apply theories formulated to describe the behaviour and life-cycles of natural systems in order to understand how societies work, how failing (or fledgling) states can be stabilised and supported, and where a military force can achieve disproportionate effects.

Societies as Complex Adaptive Systems

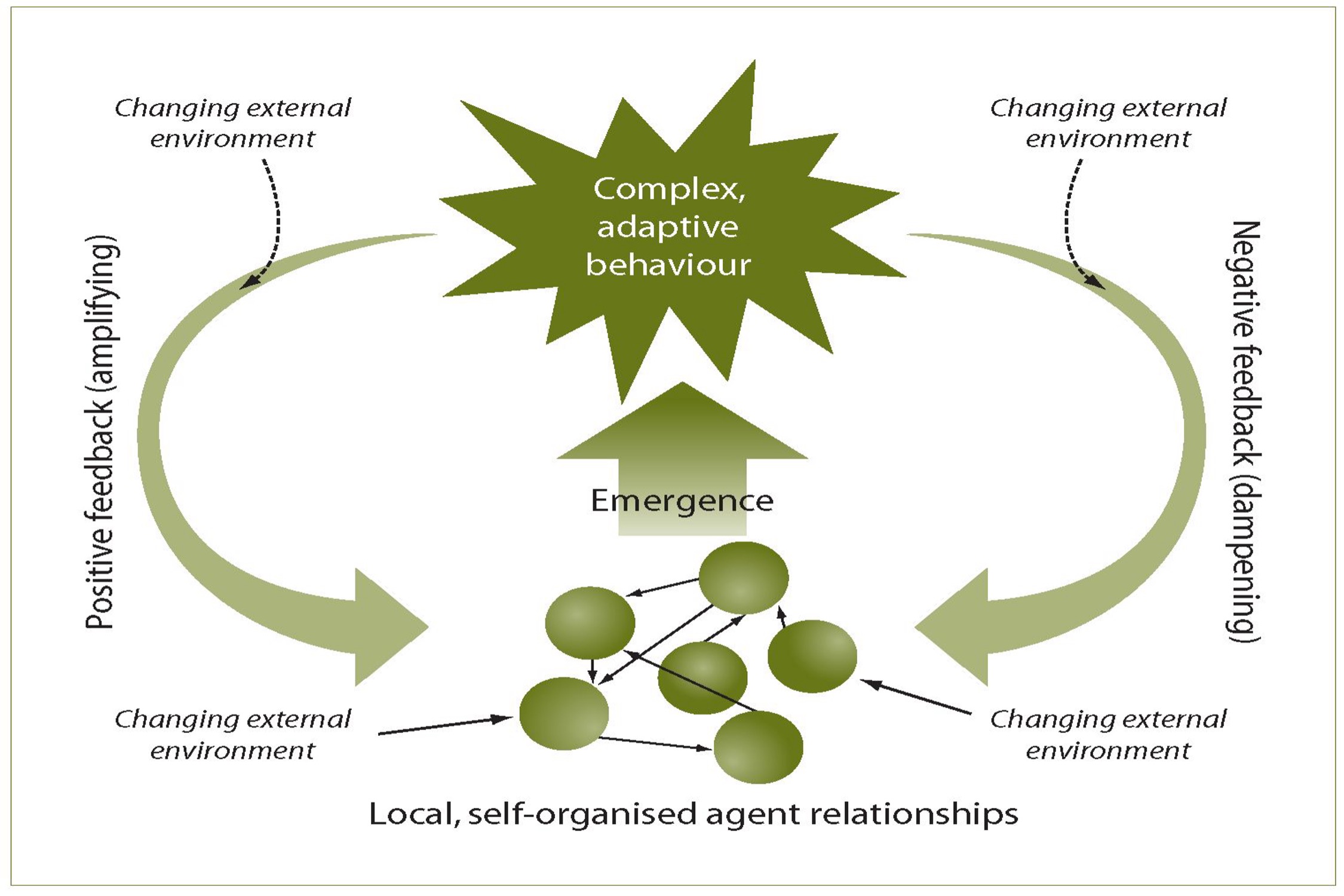

Nation-states, which are central to any stabilisation or support operation, exist as a panarchy of nested systems at different scales—referred to commonly as a ‘system of systems’? Formal and informal sources of power and authority exist based on both traditional and modern hierarchies. These are supported by stakeholders including indigenous security forces, religious and ethnic groupings, and a host of non-state actors. Sources of stress emerge as conflicting interactions between these stakeholders, and from actors that choose to challenge or operate outside the rules of the system (thus undermining the legitimacy and authority of the state). Applying an analytical approach which seeks to isolate and then concentrate on each ‘agent’ (or stakeholder) in turn, fails to efficiently identify the importance of behaviours that emerge as a result of the interactions between agents.2 These interactions, behaviours, and the positive and negative feedback cycles that control them, are more likely to provide insight into the emergence of threats to security than the modelling of agents in isolation. Consequently, it is helpful to consider the society as a complex adaptive system (Figure 1).3

Complex adaptive systems consist of agents which comprise all the component actors of the system or society. These agents may be individuals, groups or systems. They include governments, political parties, local leaderships, potential or actual insurgents and their supporters, security forces, businesses, religious groups, gangs, criminal elements, schools, universities, the media and non-government organisations. The agents interact with one another and their environment continuously in both deliberate and spontaneous ways. Some of the consequences of these interactions are linear and predictable; others are not. However, from the vast number of interactions, a pattern of behaviour emerges. This pattern of behaviour then informs the interaction of the agents (and begins to establish rules for the system) through the gains around positive and negative feedback mechanisms. Increases in the gains around positive feedback loops result in the amplification and proliferation of behaviours (be they negative or positive), while negative feedback mechanisms serve to dampen these gains and, by extension, the associated behaviours.

Feedback is critical in shaping the emergent behaviour of a complex adaptive system. It informs the actions of the agents of the system, shapes their connectivity, gives rise to the rules of the system, drives self-organising behaviour, leads to co-evolution with the environment, and results in non-linearity. In a linear system, inputs and outputs are proportionate. However, in a complex adaptive system,

Figure 1. A complex adaptive system. Simple, self-organised relationships between the system’s agents give rise to an emergent pattern of behaviour which influences the remainder of the system and its external environment, and informs subsequent agent action through negative and positive feedback loops. Successful behaviours become templates—strategies that may be learnt and copied by other agents. Variety within the agents of the system, their self-organised relationships, and memory of past successful strategies give rise to adaptive capacity and resilience. These are qualities that enable the complex adaptive system to absorb, respond to and learn from crises without collapse.4

positive and negative feedback cycles can result in disproportionate responses, unpredictable behaviour or an indeterminate relationship between cause and effect. Importantly, feedback (and non-linear feedback in particular) drives the emergence of successful strategies or templates that may then be learned, remembered and copied by other agents within the system. Once they are established, highly successful past strategies or templates (for example, the organisation of militant cadres and use of intimidation by supporters of a political party) become difficult to remove from the system.5

The Adaptive Cycle

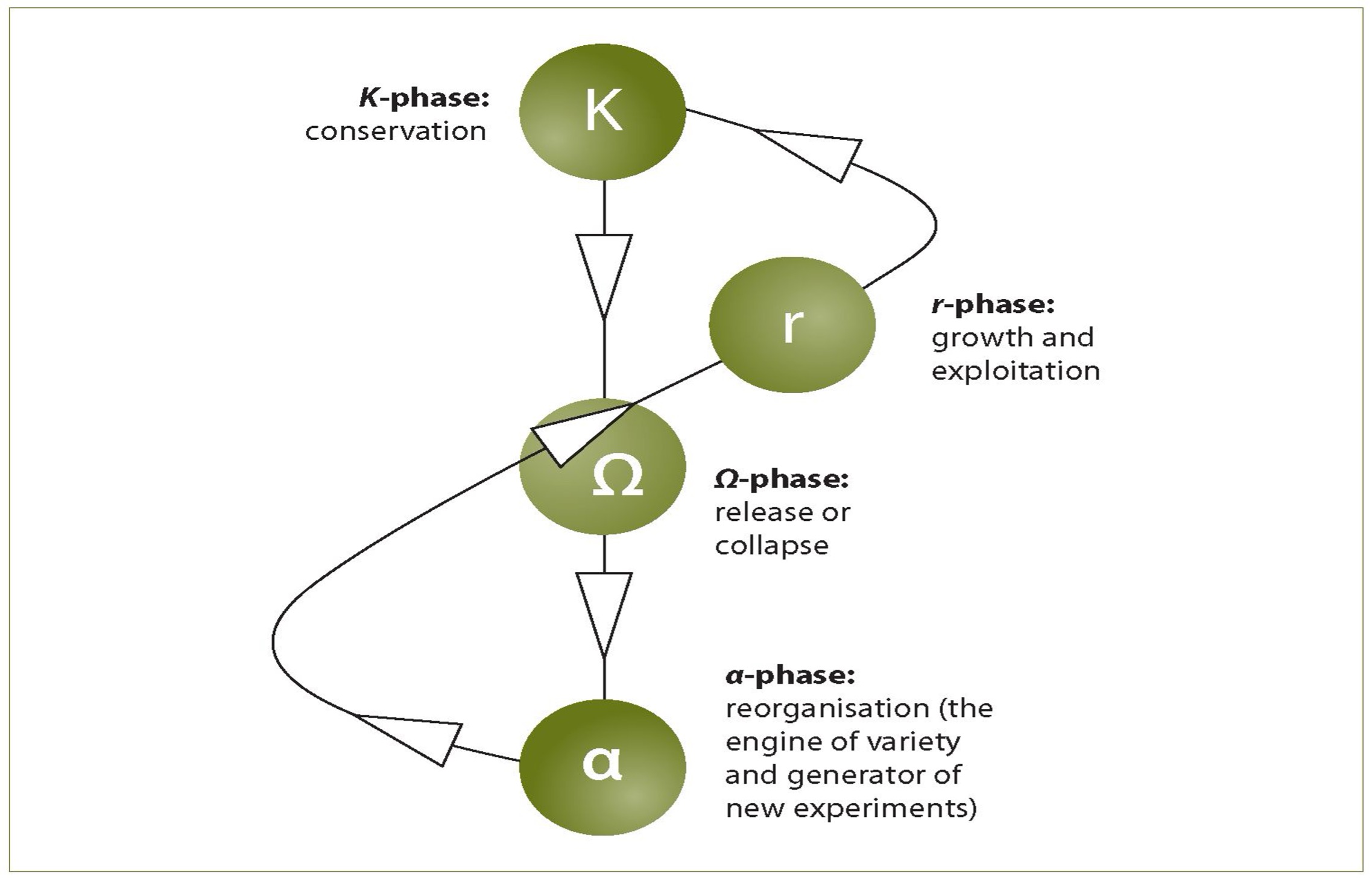

The adaptive cycle, a model derived from studying the dynamics of ecosystems, can be used to understand the life-cycle of complex adaptive systems such as the society within which a stabilisation or support operation is being conducted. This model (illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 2) is of particular relevance because the processes of destruction and reorganisation are emphasised rather than overlooked in favour of a focus on growth and conservation. The four phases in the adaptive cycle are: growth and exploitation (r); conservation (K); release or collapse (Ω); and reorganisation (α). Slow, incremental phases of growth and conservation are punctuated by more rapid collapses or releases leading to reorganisation and renewal of the system.6

Figure 2. The adaptive cycle—a life-cycle model for complex adaptive systems. In a society, the release or collapse (Ω) phase involves revolution and rapid change which may manifest as disorder, upheaval and violent conflict. The reorganisation (α) phase involves regime change and the establishment of new paradigms, rules and strategies. The new relationships and opportunities afforded by this process are exploited with strong growth during the r phase and are maintained and proliferated during the slow, conservative K phase.7

In a society that comprises a complex adaptive ‘system of systems’ or panarchy, constituent systems may be in different phases of the adaptive cycle at any point in time. For example, the political system and indigenous security forces may be in phases of reorganisation (α) while aid, investment and the exploitation of natural resources have driven the economic system into the growth (r) phase. If one system within the panarchy—the political, economic or security system for instance—enters a release or collapse (Ω) phase, it may trigger a crisis, catalysing the collapse of other systems (known as a ‘revolt’ connection). Alternatively, the strategies, templates and resilience of larger, slower systems within the panarchy may heavily influence the subsequent reorganisation (α) phase (known as a ‘remember’ connection).8

Resilience and the related concept of adaptive capacity are critical to the stability of a complex adaptive system, and work to prolong the period between phases of release or collapse (Ω), reduce the likelihood of ‘revolt’ connectionbased crises, and increase the stabilising effect of ‘remember’ connections. Resilience refers to the capacity of the system to absorb and tolerate disturbance without collapsing (retaining structure and function), while adaptive capacity relates to the ability of the system’s agents to learn and store knowledge and experience, creating flexibility in problem-solving. Resilience and adaptive capacity are interdependent, and diversity (or functional redundancy) is fundamental to both.9

Stabilisation and support operations are likely to be conducted in response to a release or collapse (Ω) phase in the life-cycle of a social system and may be designed to reduce the severity of this transition or guide the subsequent reorganisation and renewal (α and r phases) to ensure that undesirable strategies and templates (such as corruption, radical ideology, politically motivated violence or organised crime) do not flourish. From a systemic perspective, the military force is employed to alter system feedback to ensure that such behaviours are unproductive, while desirable strategies and templates are generated, supported and reinforced. The military force also contributes to the resilience of the system by buffering shocks to the nascent indigenous political and security apparatus, and can increase adaptive capacity through mentoring and advisory approaches. Effectively, stabilisation and support operations represent an effort to generate a ‘remember’ connection between the social system in collapse and the more stable societal systems represented by the contributors from the military force.

Applying the Theory to Stabilisation and Support Operations

So how is complexity theory applied to military appreciation processes? Within the panarchy of the target society, some agents (including international forces), interactions and behaviours act as sources of stress, others as sources of resilience, while others simply exist as symptoms (or outputs) of the system’s functioning. In the conduct of stabilisation or support operations, anti-insurgency and indigenous capacity-building objectives can be accomplished through the identification of sources of resilience to sustain and enhance (through the creation or amplification of positive feedback loops) and the nomination of targetable sources of stress to neutralise or repress (through the creation or reinforcement of negative feedback loops).10 Such an approach is not novel in warfighting theory, having been postulated in a variety of forms since the advancement of Soviet deep-operations doctrine in the 1920s.11 However, this approach can also be used to develop the tactical and operational actions or decisive effects required to populate imposed (specified) lines of operation such as Adaptive Campaigning 2009’s joint land combat, population protection, information actions, population support and indigenous capacity-building.12

In the first instance, the range of critical sub-systems and their stakeholders, which act as important agents within the complex adaptive system, should be identified. These may include political parties and leaderships, gangs and groups, markets and business interests, security forces and militias, religious and ethnic groupings and both international state and non-state actors. From a reductionist analytical point of view, each of these stakeholders has its own centre of gravity, critical capabilities, requirements and vulnerabilities, and available courses of action. All these may need to be determined and assessed. Next, the relationships between these stakeholders should be examined. While many of these will be complex and opaque, understanding these interactions is critical as they govern the emerging behaviour of the complex adaptive system when iterated through positive or negative feedback cycles. Identifying which agents and interactions contribute to sources of stress (crime, lack of faith in security and the justice system, lack of availability of food, unemployment, poor access to services) and which act as sources of resilience (cultural identity, social groupings, traditional laws and leaderships, agriculture, religion and education) will provide a set of possible points where leverage may be applied to the system. This set will, of course, need to be refined, based on access and appropriateness for the military force within the whole-of-government effort, and given the resources available.

The points of leverage or ‘levers’ which may be used to produce disproportionate effects on targets identified within a complex adaptive system can be drawn from systems theory.13 A subset of these levers is readily applicable to a military force conducting stabilisation and support operations. In order of increasing power, this subset includes: monitoring and observing parameters in order to measure operational effectiveness and identify sources of systemic stress and resilience; contributing to the buffering of the system by adding capability and resilience to the security apparatus; alternative reinforcement and dampening of negative feedback loops by enacting or supporting the disruption of threat agents and subversive activities; alternative reinforcement and dampening of positive feedback loops through information actions and contributions to the security of positive templates; improving the flow of information supporting positive templates and discouraging harmful strategies through information actions; ensuring adherence to the rules of the system by monitoring and focusing attention on transgressions; and, where advisory capacity allows, influencing and reinforcing positive developments in the structure of the system and its goals. Ultimately, the use of these levers formalises the requirement to identify and monitor sources of stress and subversion, protect and reinforce successful strategies, build and generate successful templates, and dislocate or disrupt threats, subversive activities and harmful templates. Command and staff recognition of the paramount importance of innovative, thoughtful and proactive information actions and engagement in this process is essential for success. Commanders must also recognise that complex systems are often counter-intuitive and that, in some cases, the ‘cure may be worse than the disease’.14

Given the inherent non-linearity—and therefore unpredictability—in the response of a complex system to actions that alter its feedback mechanisms and information flows, the actions of the military force conducting the stabilisation or support operation are likely to be ‘effects-seeking’ rather than ‘effects-based’.15 Consequently, measuring the effect and the effectiveness of the actions taken by the military force and then adjusting those actions accordingly, is of paramount importance. This requirement is encapsulated succinctly from a doctrinal perspective in the adaptation or ASDA cycle (act, sense, decide, adapt).16 The most difficult task lies in assessing the effect that has been generated, an assessment that relies on the effective monitoring of carefully selected, culturally perceptive measures of performance (MOP) and effectiveness (MOE). These measures are necessarily specific to the societal system in question, but comprise an excellent start point and use specific methodology published by the United States Institute of Peace.17 Additional consideration should be given to breaking down MOP and MOE according to the appropriate scale they reflect. This will potentially yield micro-MOP/MOE for sub-systems and inform macro-MOP/MOE for the system as a whole. Academic consultation with groups such as the Defence Science and Technology Organisation could be helpful in designing such metrics.

The approach detailed in this discussion (summarised in Table 1), governed as it is by the need to use and measure influence in the absence of a readily quantifiable threat, demands disproportionate attention to information actions, civil-military cooperation and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities. Information actions, ranging from media product to key leadership engagement and the messages or ‘talking points’ briefed to every patrolling soldier, allow the military force to support successful templates and discourage harmful strategies.

Table 1. Applying complexity theory to the appreciation processes for stabilisation and support operations.

|

1. |

Identify the key sub-systems and their actors. |

J/IPMB (complex human, informational and physical terrain). |

|

2. |

Identify the relationships between the actors. |

As above. |

|

3. |

Identify which actors and relationships function as sources of resilience and which constitute sources of stress on the system. |

As above. |

|

4. |

Develop decisive points along specified lines of operation to: • Build, protect and reinforce sources of resilience (successful strategies). • Deter, dislocate or disrupt sources of stress (threats and subversive activities). |

J/MAP: mission analysis. |

|

5. |

Develop and monitor measures of performance and effectiveness. |

J/MAP: course of action development, analysis, and in execution through an ongoing targeting process. |

|

6. |

Adapt actions based on the effects that have been generated through continuous review. |

In execution through an ongoing targeting process. |

Information actions used to seek this type of leverage must be clearly distinguished from public affairs campaigns promoting the military force. Information actions focus on amplifying and promoting examples of indigenous resilience and adaptive capacity (such as the successes achieved by local security forces or community organisations). Sources of resilience, adaptive capacity and harmony within the community can be reinforced through civil-military cooperation, and should serve as the discriminator for project selection (rather than a preoccupation with ‘consentwinning tasks’ delivering doubtful flow-on benefits to stability or to indigenous capacity). Finally, identifying the opportunities for these actions and monitoring measures of effectiveness require the entire military force to maintain an informed awareness of its intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance role.

Conclusion

Complexity theory affords commanders and their staff a useful ‘lens’ through which to view their tasks during the planning of stabilisation and support operations, and also provides a means to conduct targeting in the absence of clearly distinguishable (or illegal) threats to the security of the host nation. When used to augment the framework of doctrinal decision-making tools such as the IPMB and the J/MAP, complexity theory enhances the utility of these tools away from their well-understood application to conventional and counterinsurgency warfare. A systemic (rather than analytic) approach, focusing on interactions and feedback mechanisms rather than concentrating on agents, will offer insights on where to apply leverage so as to contribute to the development of security and stability within a society. The targeting derived from such an approach will focus on building and fostering identified sources of resilience and adaptive capacity within the host nation, while mitigating or disrupting sources of stress. Complexity theory highlights the non-linearity of feedback mechanisms, implying a requirement for the continuous monitoring of measures of effectiveness in order to adapt effects-seeking operations. In analysing progress using these measures of effectiveness, viewing the society as a complex adaptive system evolving in an adaptive cycle provides a valuable understanding of where the host nation lies on its continuum of development. However, complexity theory does not promise certainty and, in its practical application, it does not permit the reduction of complex problems to simplicity. It allows commanders to identify more places to act, but imposes a requirement to decide on the appropriateness of such actions and then closely monitor the effects generated.

Endnotes

1 C Holling, L Gunderson and G Peterson, ‘Sustainability and Panarchies’ in L Gunderson and C Holling (eds), Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems, Island Press, Washington, 2002, pp. 63–75.

2 K Glenn, Complex Targeting: A Complexity-Based Theory of Targeting and its Application to Radical Islamic Terrorism, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, 2002, p. 14.

3 A Battram, Navigating Complexity, Stylus, Sterling, 1998, p. 38; Glenn, Complex Targeting, pp. 28–41; and ‘Trojan Mice’, <http://www.trojanmice.com/index.htm> accessed 4 May 2009.

4 Ibid.

5 Glenn, Complex Targeting, pp. 28–41.

6 C Holling and L Gunderson, ‘Resilience and Adaptive Cycles’ in Gunderson and Holling (eds), Panarchy, pp. 25–62.

7 Ibid., p. 34.

8 Holling, Gunderson and Peterson, ‘Sustainability and Panarchies’ in Panarchy, p. 75.

9 C Folke, J Colding and F Berkes, ‘Building Resilience for Adaptive Capacity in Social-Ecological Systems’ in F Berkes, J Colding and C Folke (eds), Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, pp. 352–65.

10 W Stothart (Commanding Officer), 3 RAR 611-7-8, Timor Leste Battlegroup IV Post Operation Report: Op ASTUTE, 2008, pp. 1–8.

11 J Kelly and D Kilcullen, ‘Chaos Versus Predictability: A Critique of Effects-Based Operations’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, p. 88.

12 Head Capability Development Army, Adaptive Campaigning 2009: Realising an Adaptive Army, Department of Defence, Canberra, March 2009, pp. 13–14.

13 D Meadows, Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System, The Sustainability Institute, Hartland, 1999.

14 J Forrester, ‘Counterintuitive Behaviour of Social Systems’, Technology Review, 1971, pp. 6–7.

15 Kelly and Kilcullen, ‘Chaos Versus Predictability’, pp. 89–97.

16 Head Capability Development Army, Adaptive Campaigning 2009, Department of Defence, Canberra, pp. 16–18.

17 United States Institute of Peace, ‘Measuring Progress in Conflict Environments (MPICE) Metrics Framework for Assessing Conflict Transformation and Stabilisation’, February 2008, <http://www.usip.org/peaceops/metrics_framework.html> accessed 18 May 2009.