Introduction

A 2020 paper published in the Australian Army Journal (AAJ) outlined that the success of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army (ADFGY-A) program that ran from 2007 to 2012 was not as clear as the rhetoric of the day suggested.[1] A low transfer rate into the Permanent Force coupled with ambiguity around its purpose gave reasonable cause to question whether the program represented value for money or whether it was even effective as an alternative avenue of entry.

After a hiatus of three years, Army reintroduced the ADFGY-A program in 2015. Its reintroduction was an election promise of the coalition government and provided Army with an opportunity to implement changes that were intended to address the criticisms of the first program. On 12 January 2015, the first intake of participants into the new program were enlisted and by the end of June 2022 a cumulative total of 2,160 had commenced the other ranks (OR) component.[2]

As with the paper published in 2020, the aim of this article is to examine the Gap Year completion rate and subsequent transfer into the Permanent Force or Reserves among OR[3] participants who enlisted in the program from January 2015.[4] To establish context and to allow the 2015 program to be compared against its 2007–2012 predecessor, the key changes and reforms made to the program will first be highlighted. This will be followed by detail on recruitment, completion and retention outcomes exhibited so far. Common themes, observations and recommendations arising from both programs will be drawn together in the discussion towards the end of this article.

Previous Findings about the 2007–2012 ADFGY-A Program

By the time it ended, 1,630 participants had been recruited into the 2007–2012 ADFGY-A program. Immediately after or during the program, 32.8 per cent of participants had transitioned into the Australian Regular Army (Permanent Force roles currently described as SERCAT 6 and 7) and an additional 32 per cent had transitioned into the Army Reserve (roles currently described as SERCAT 3, 4 and 5). The remaining 35.2 per cent either separated or transferred into the Standby Reserves (currently described as SERCAT 2).

It was anticipated that retention of Gap Year participants in the Permanent Force after participation in the 2007–2012 program would be good, with policy and processes specifically developed to facilitate transfer.[5] It was implied that those not wishing to continue would self-select out of the Army in a ‘try before you buy’ approach, thereby leaving only those in service who were sufficiently motivated towards a longer-term Army career.[6] However, separation rates for participants continuing in the Permanent Force did not differ markedly from those of entrants through normal ab initio avenues. After four additional years in the Permanent Force (around five years in total), only 26.3 per cent of the original participants remained. Retention in the Reserves did not fare any better, with only 16 per cent of the original participants serving in the Active Reserves four years after they participated in the Gap Year.

Some of the main criticisms levelled at the 2007–2012 program were oriented around its purpose and whether it was intended to provide an experience for its participants or whether it was actually a recruitment opportunity. As a result of the lack of clear purpose from the outset, Army systems were not sufficiently flexible to provide participants who wanted to continue in the Permanent Force an opportunity to do so, thereby limiting the program’s effectiveness as a recruiting avenue of entry. Eventually, training capacity and funding constraints resulted in reductions to the intake sizes such that the objective of offering a wide range of Army experiences to a large number of participants was also compromised. The reduced intake levels and high separation rates of participants who were trained to the level of full-time capability contributed to Defence’s assessment that the program was an ineffective and costly avenue of entry that could not be sustained. As a result, it was suspended in 2012.[7]

Comparison of the 2007 and 2015 ADFGY-A Program Structures

With a similar aim to its predecessor, the 2015 program offers ‘to provide young Australians with the opportunity to gain experience as a member of the Australian Army for up to one year’.[8] Also as with its predecessor, there is ambiguity in its purpose, with Army’s policy suggesting that the program ‘provides a contemporary pathway into the Australian Army’ with an emphasis on retention after the Gap Year. This incongruity between a recruiting objective and an experiential objective (the latter which does not imply retention in order for the program to be successful) has so far plagued analysis of the success of both programs.

Although it is easy to dismiss incongruity of purpose as a semantic matter, the mere existence of a discrepancy in objective has the potential to result in conflict in program administration and management. For example, the allocation of resources towards an experience versus retention or transition, and the approach taken towards marketing and attraction as a Gap Year or an alternative avenue of entry, are fundamentally different and implicitly connected to the objective of the program. Therefore, clarity of purpose remains essential in obtaining effective outcomes.

Setting aside the continued ambiguity in the program’s objective, other more tangible characteristics such as the participant selection criteria remain similar. ADFGY-A is still intended to attract a slightly different and narrower recruiting demographic than normal ab initio avenues by appealing to post-secondary young Australians.[9] Additionally, the education, aptitude and age requirements of participants remain consistent between the programs and, despite the ambiguous policy statements, there remains no compulsion to continue to serve in the ADF after completion of the program.[10]

There are several key differences in the conduct and administration of the program that have been implemented since 2015, partially in response to criticism surrounding the first program, and partially to capitalise on opportunities that were previously missed. Notably, formal responsibilities have been assigned to monitor the progress of participants, provide individualised advice, and facilitate transition into the Permanent Force or, at the very least, into the Reserves. This approach provides options for closer individual monitoring and management of participants, along with an effective feedback loop for improvements and advice to both the participant’s chain of command and Army’s leadership regarding the program itself.

There are other fundamental changes incorporated into the second program that offer benefits to both Army and the participant. For example, there has been a reduction in the number of employment categories available for participants from 23 to just seven. The roles now available are those where participants can be sufficiently trained with enough time remaining to experience at least a few months in a unit environment prior to the end of their Gap Year. Recruiting into a generic employment category known as General Enlistment (ECN500), prior to allocation to a specific employment category near the end of initial military training, was closed. This change allowed for more certainty for both training establishments and participants while providing for more focused approaches to marketing and attraction.[11] Additionally, participants are assured that, if they want to transition into the Permanent Force, then a position will be made available for them—an assurance that was not available for participants in the first ADFGY-A program (perhaps a consequence of an experiential rather than a recruitment objective). Finally, the ADFGY-A participant intake itself only occurs in the first quarter of each calendar year, so it is better synchronised with the intent of a post-secondary gap year. It also consolidates participants into a handful of recruit platoons, providing a more common experience for participants and enabling better programming throughout training and subsequent posting activities.

ANALYSIS DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Gap Year participants are specifically recorded and identified in Defence’s human resource system (Defence One). This allows all participants to be accurately tracked throughout their time in the program along with any subsequent service in the Permanent Force or the Reserves. For this analysis, data fields obtained included the Gap Year enlistment date, employment category, sex, separation or transfer date, and any subsequent movements into another Service Category (SERCAT) or Service Option (SERVOP).[12] The following analysis of Gap Year is approached from three perspectives: achievement of ADFGY-A recruitment targets, completion of the program and transfer into the Permanent Force or Reserves, and post-program retention of participants who had transferred into the Permanent Force or Reserves.

RESULTS

The first candidates who were enlisted into the revised ADFGY-A program commenced on 12 January 2015. Regular intakes then followed from January to March each year to align with the training courses for specific employment categories. By the end of June 2022, 2,160 OR participants had commenced the program over the eight years since its inception, with the program ongoing.

Recruitment Outcomes

The program has remained popular with applicants (as it was throughout 2007–12) and it is normal for Defence Force Recruiting to receive far more applicants than there are positions for all employment categories. This situation most likely reflects the continued positive employment value proposition that provides successful applicants with training, salary and experiences with no specific obligation period after completing the program. The marketing approach of ‘spend an exciting 12 months in the Navy, Army or Air Force, where you’ll get paid for meaningful work while travelling around Australia, gaining skills for life, and making lifelong friends’ still appears to resonate.

Table 1 shows the recruitment outcomes from financial year (FY) 2014–15 to FY 2021–22 for each employment category, while Table 2 shows a breakdown by sex (correct at 1 January 2023).[13] Based on this data, there appear to be some positive attributes that are unique to Gap Year. Specifically, females are recruited into ADFGY-A combat roles at higher ratios than through ab initio avenues (14 per cent of participants in combat roles are women).[14] For other roles, it also seems that Gap Year has a positive influence on female recruitment outcomes (43 per cent of participants in non-combat roles are women). It can be speculated that this outcome could be attributable to the Gap Year employment offer having no obligation to continue to serve once the applicant completes the program. Due to the limited employment categories available, and the likelihood of competition between avenues, a direct comparison with ab initio avenues cannot be made. Consequently, the benefit of the program to improving gender diversity outcomes cannot be ascertained with precision. However, it is reasonable to suggest that there might have been some marginal contribution to Army’s overall recruitment outcomes for women.

|

Employment Category |

Recruiting Year |

Total |

|||||||

|

FY14/15 |

FY15/16 |

FY16/17 |

FY17/18 |

FY18/19 |

FY19/20 |

FY20/21 |

FY21/22 |

||

| Artillery Gunner |

25 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

13 |

29 |

|

112 |

|

| Combat Engineer |

|

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

|

96 |

||

| Command Support Clerk |

19 |

26 |

38 |

39 |

37 |

27 |

29 |

|

215 |

| Distribution Operator |

40 |

26 |

48 |

48 |

50 |

50 |

58 |

|

320 |

| Driver Specialist |

38 |

47 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

47 |

49 |

|

325 |

| Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems |

|

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

|

56 |

||

| Infantry Soldier |

103 |

126 |

137 |

112 |

82 |

95 |

85 |

|

740 |

| General Enlistment* |

|

296 |

296 |

||||||

| Total Recruited |

200 |

250 |

300 |

300 |

270 |

270 |

274 |

271 |

2,160 |

| Target |

200 |

250 |

300 |

300 |

270 |

270 |

270 |

270 |

2,130 |

*From 2022 new entrants into the program were recruited into a combat or support segment and allocated to an Employment Category during Initial Military Training.

Table 1. ADFGY-A recruiting targets and outcomes (FY 2014–15 to FY 2021–22)

| Employment Category |

Female |

Male |

Total |

| Artillery Gunner (ECN 162) |

26 |

86 |

112 |

| Combat Engineer (ECN 096) |

23 |

73 |

96 |

| Command Support Clerk (ECN 150) |

91 |

124 |

215 |

| Distribution Operator (ECN 104) |

97 |

223 |

320 |

| Driver Specialist (ECN 274) |

179 |

146 |

325 |

| General Enlistment (ECN 500)* |

71 |

225 |

296 |

| Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems (ECN 237) |

14 |

42 |

56 |

| Rifleman (ECN 343) |

79 |

661 |

740 |

| Grand Total |

580 |

1,580 |

2,160 |

Table 2. ADFGY-A recruiting outcomes by sex

Completion of Gap Year and Transfer into the Permanent Force and Reserves

The results in Table 3 detail the completion and transfer outcomes for the FY 2014–15 to FY 2020–21 cohorts, representing 1,864 participants (validated as at 1 January 2023).[15] While there were 2,160 participants to 1 July 2022, the most recent 2022 cohort of 296 has not yet had an opportunity to complete the program and is therefore excluded from Table 3 until the transfer outcomes of the entire cohort are known.[16]

The participant completion rate is similar to that of the earlier 2007–2012 program, with around 80 per cent completing the program or transferring to the Permanent Force or Reserves. Additionally, early loss rates are comparable to other OR ab initio avenues, where around 20 per cent of any starting cohort separate before completion of training or the first year of service.[17]

In a significant improvement on outcomes from the 2007–2012 program, just over 57 per cent of participants transfer into the Permanent Force after the program (which may have occurred during or immediately after the Gap Year). An additional 23 per cent transfer into the Reserves, comprising 16 per cent into the Active Reserves (currently referred to as SERCAT 3, 4 and 5) and 7 per cent into the Standby Reserves (SERCAT 2). Almost 20 per cent separate altogether.

There is a substantial difference between employment categories, with the transfer of infantry soldier and artillery gunner participants into the Permanent Force significantly below the average, while the percentage of combat engineer and driver participants is higher. Separation figures also differ between employment categories, with over a quarter of all infantry soldier participants separating from Army altogether, compared with around 8 per cent of combat engineer and 10 per cent of command support clerk participants.

The difference in completion rates between combat and combat support categories is notable and may suggest that ADFGY-A has different rates of efficacy across the employment categories. The program appears to have been particularly effective in recruiting and retaining combat engineers, which, despite only being included in ADFGY-A since 2018, is the employment category with the highest transfer rate and lowest rate of separation. This situation contrasts with the infantry soldier category, which is popular and oversubscribed but has low transfer rates into the Permanent Force. Indeed, this category achieves barely average transfer rates into the Reserves (despite many opportunities in Reserve roles), and higher separation than all other available employment categories.

Females generally had higher rates of completion and transfer than males. As shown in Table 3, over 84 per cent of women completed the program or transferred, compared with less than 79 per cent of males. At the employment category level, female artillery gunners and infantry soldiers had substantially higher transfer rates into the Permanent Force and lower separation rates (during the program) than their male counterparts. This provides some support for Army’s ongoing initiative of lower obligation periods for women applying for these roles through ab initio avenues of two years, but also raises questions as to why a one-year program with no ongoing service obligation would result in substantially different outcomes than a two-year ab initio obligation.

Unfortunately, when assessing the program against its objectives, comparisons against an average, other employment categories or other sex are constraining and not necessarily useful. However, there is little choice but to use these types of metrics because, while averages and comparisons do not provide a context of ‘good or bad’ or ‘desirable or undesirable’, Army has established no performance or success criteria for what it expects or hopes from the Gap Year program. Consequently, the following discussion remains necessarily oriented around relative comparisons in relation to transition and separation.

| Employment Category |

Total Participants |

ADFGY-A Completion |

Transfer During or After Gap Year Participation |

|||||||||

|

Permanent Force SERCAT 6, 7 |

Reserves SERCAT 3, 4, 5 |

Standby Reserves SERCAT 2 |

Separation |

|||||||||

| Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Artillery Gunner (ECN 162) |

|

26 |

23 |

88.5% |

20 |

76.9% |

2 |

7.7% |

1 |

3.8% |

3 |

11.5% |

| Combat Engineer (ECN 096) |

|

23 |

22 |

95.7% |

13 |

56.5% |

7 |

30.4% |

2 |

8.7% |

1 |

4.3% |

| Command Support Clerk (ECN 150) |

|

91 |

79 |

86.8% |

63 |

69.2% |

10 |

11.0% |

6 |

6.6% |

12 |

13.2% |

| Distribution Operator (ECN 104) |

|

97 |

73 |

75.3% |

53 |

54.6% |

14 |

14.4% |

6 |

6.2% |

24 |

24.7% |

| Driver Specialist (ECN 274) |

|

179 |

156 |

87.2% |

115 |

64.2% |

36 |

20.1% |

5 |

2.8% |

23 |

12.8% |

| Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems (ECN 237) |

|

14 |

13 |

92.9% |

9 |

64.3% |

4 |

28.6% |

|

0.0% |

1 |

7.1% |

| Infantry Soldier (ECN 343) |

|

79 |

63 |

79.7% |

48 |

60.8% |

12 |

15.2% |

3 |

3.8% |

16 |

20.2% |

| Female Total |

|

509 |

429 |

84.3% |

321 |

63.1% |

85 |

16.7% |

23 |

4.5% |

80 |

15.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Artillery Gunner (ECN 162) |

|

86 |

70 |

81.4% |

48 |

55.8% |

13 |

15.1% |

9 |

10.4% |

16 |

18.6% |

| Combat Engineer (ECN 096) |

|

73 |

66 |

90.4% |

55 |

75.3% |

6 |

8.22% |

5 |

6.8% |

7 |

9.6% |

| Command Support Clerk (ECN 150) |

|

124 |

114 |

92.7% |

77 |

62.1% |

29 |

23.4% |

8 |

6.4% |

10 |

8.1% |

| Distribution Operator (ECN 104) |

|

223 |

181 |

81.2% |

120 |

53.8% |

38 |

17.0% |

23 |

10.3% |

42 |

18.8% |

| Driver Specialist (ECN 274) |

|

146 |

120 |

82.2% |

95 |

65.1% |

17 |

11.6% |

8 |

5.5% |

26 |

17.8% |

| Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems (ECN 237) |

|

42 |

37 |

88.1% |

24 |

57.1% |

8 |

19.0% |

5 |

11.9% |

5 |

11.9% |

| Infantry Soldier (ECN 343) |

|

661 |

480 |

72.6% |

328 |

49.6% |

107 |

16.2% |

45 |

6.8% |

181 |

27.4% |

| Male Total |

|

1,355 |

1,068 |

78.9% |

747 |

55.1% |

218 |

16.1% |

103 |

7.6% |

287 |

21.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grand Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Artillery Gunner (ECN 162) |

|

112 |

93 |

83.0% |

68 |

60.7% |

15 |

13.4% |

10 |

8.9% |

19 |

17.0% |

| Combat Engineer (ECN 096) |

|

96 |

88 |

91.7% |

68 |

70.8% |

13 |

13.5% |

7 |

7.3% |

8 |

8.3% |

| Command Support Clerk (ECN 150) |

|

215 |

193 |

89.8% |

140 |

65.1% |

39 |

18.1% |

14 |

6.5% |

22 |

10.2% |

| Distribution Operator (ECN 104) |

|

320 |

254 |

79.4% |

173 |

54.1% |

52 |

16.2% |

29 |

9.1% |

66 |

20.6% |

| Driver Specialist (ECN 274) |

|

325 |

276 |

84.9% |

210 |

64.6% |

53 |

16.3% |

13 |

4.0% |

49 |

15.1% |

| Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems (ECN 237) |

|

56 |

50 |

89.3% |

33 |

58.9% |

12 |

21.4% |

5 |

8.9% |

6 |

10.7% |

| Infantry Soldier (ECN 343) |

|

740 |

543 |

73.4% |

376 |

50.8% |

119 |

16.1% |

48 |

6.5% |

197 |

26.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grand Total |

|

1,864 |

1,497 |

80.3% |

1,066 |

57.2% |

303 |

16.3% |

126 |

6.8% |

367 |

19.7% |

Table 3. ADFGY-A completion and transfer outcomes (FY 2014–15 to FY 2020–21) by sex and total

Post-Program Retention

While just over 57 per cent of program participants transferred into the Permanent Force or Reserves immediately after completion, their ongoing retention also remains a significant indicator of program success (where recruitment is an objective of the program). As with the 2007–2012 program, it is interpreted that those remaining in the Army after completion of the program are sufficiently motivated toward a long-term career, owing to the numerous opportunities to self-select out during their Gap Year.

Complete analysis of retention outcomes requires that a sufficient period has elapsed since the cohorts first commenced and completed the program. For this analysis, retention to the four-year mark is chosen as the benchmark because it is the same obligation period that would be applied to most individuals if they were recruited through ab initio avenues (less women recruited with a two-year obligation). This narrows the data from which to analyse retention to the first four ADFGY-A cohorts (financial years 2014–15, 2015–16, 2016–17 and 2017–18), in which there were 1,050 participants.[18] For these cohorts, by the end of the first 12 months of the program, 55 per cent of participants had transitioned into the Permanent Force, 17 per cent into SERCAT 3 or 5, and 8 per cent into SERCAT 2. Around 18 per cent had separated altogether and the remaining 2 per cent remained in the program for a range of reasons.[19]

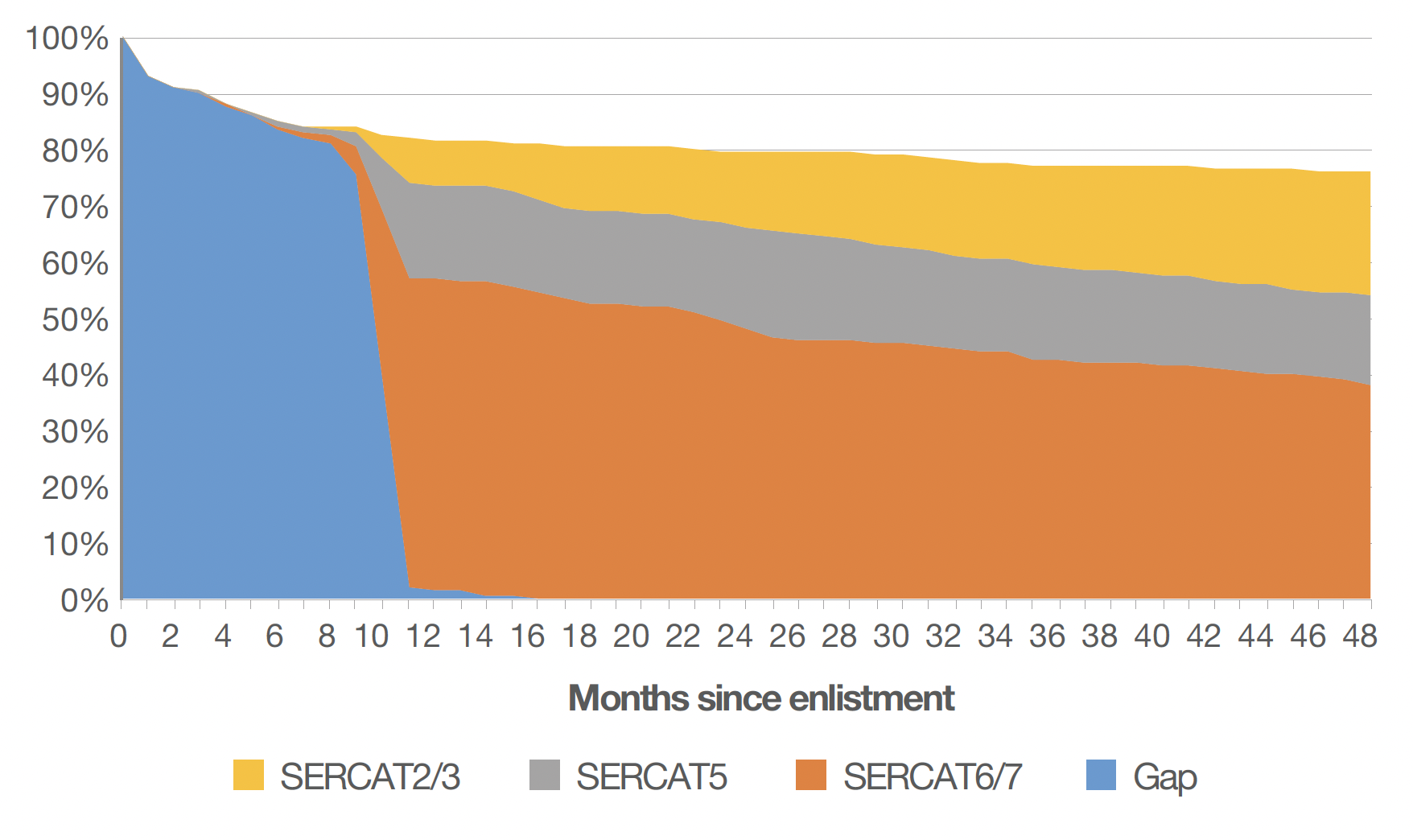

The ongoing retention rate of participants to the four-year mark is shown in Figure 1. While 55 per cent of the financial year 2014–15 to 2017–18 cohorts ultimately entered the Permanent Force during or immediately after their Gap Year, three years later (four years in total) just 38 per cent remained. This decrease from 55 per cent to 38 per cent (17 per cent) equates to 31 per cent of ADFGY-A participants who transitioned to the Permanent Force after completion of the program subsequently choosing to separate or transfer to the Reserves before completing a total of four years of service (and after the first year). This figure is useful for comparison with other avenues of entry.

The ADFGY-A and normal ab initio populations differ markedly in several of the characteristics mentioned earlier, such as age, aptitude, education and service obligation; however, cautious comparisons can be made. While 38 per cent of Gap Year participants completed a total of four years of service in the Permanent Force, over 65 per cent of those recruited through ab initio avenues completed the same length of service.[20] Unfortunately, this direct comparison is dubious because ADFGY-A participants are under no obligation to undertake further service after completion of the program, unlike their ab initio counterparts, who typically have a four-year obligation period. However, once the first year is set aside and only those former Gap Year participants who transferred to the Permanent Force are considered, proportionately more (31 per cent) will still leave after one and before the end of four years than the 20 per cent of those recruited through ab initio avenues who leave during the same period in a career.

While a benefit to the Reserves has been mentioned as a secondary outcome of ADFGY-A,[21] the level of reserve activity undertaken by participants after they transfer to the Reserves is not high. Of the 261 participants who transferred to the Reserves (SERCAT 2, 3 or 5 from the same four cohorts mentioned above), only 110 (42 per cent) paraded for 21 days or more in any subsequent year until the end of FY 2021–22. Of these, 24 only achieved this milestone once following completion of the program. When those who initially transferred to the Standby Reserve (SERCAT 2) are considered in isolation, only 10 of 83 undertook 21 days or more of effective service in the years after completing the program, nine of whom transferred to SERCAT 5 before doing so.

Figure 1. Retention of ADFGY-A participants (FY 2014–15 to FY 2017–18 inclusive)—first 48 months

Is the 2015 Gap Year a Success?

An assessment of the program depends primarily on the lens through which success is defined. As discussed in this and the previous AAJ paper, a claim of success depends on whether the program’s objective is viewed as experiential or an alternative avenue of entry to the Australian Defence Force. Several observations made in this paper suggest that, while an experiential objective remains in policy and some marketing material, this is far from the reality of Army’s intent for the program. It is notable that neither the Army nor the equivalent schemes of the other Services have undertaken any research to ascertain whether participants took their positive experiences of military service acquired during their Gap Year into the broader community, whether this had positive implications for the nation or Defence, or even whether the individuals themselves benefited from their Gap Year experience. Therefore, success against an experiential objective remains the subject of speculation and it is likely that the practicalities of recruiting and the achievement of targets has become the dominant consideration for Army over simple experiences for participants.

Recruiting Success

For the purpose of further discussion, it is pragmatic to infer that Army considers the program’s objective as being an alternative avenue of entry to the ADF, particularly given its recruiting success. However, it is unclear whether the program competes against the usual ab initio avenue for the same applicants, or results in an overall increase across all avenues. It is not possible to reliably conclude that the program contributed to an increase in total recruiting above that which would be achieved if ADFGY-A did not exist at all. Therefore, a larger ADFGY-A may not be a panacea for Army’s ongoing recruitment shortfalls, despite its apparent success in attracting candidates to the program.

Nonetheless, the current structure of the program provides some insight regarding the program’s capacity to assist with recruitment outcomes. Specifically:

- When employment categories are oversubscribed (i.e. have more applicants than positions), it makes no difference whether those targets are met through one or many avenues of entry. For these employment categories, ADGFY-A serves no purpose in improving recruiting outcomes. Therefore, it would be fair to conclude that they likely remain an offering within the program only to ensure that a range of roles are available to prospective candidates. If the transfer of participants into the Permanent Force at the end of their Gap Year is not what Army requires or was expecting, then it is entirely plausible that ADFGY-A may actually be detrimental to short-term recruiting into the Permanent Force.

- When employment categories are undersubscribed (i.e. there are not enough applicants in the absence of a Gap Year program), then a net positive outcome will only occur if the Gap Year offer operates to attract more applicants in total than could be achieved if normal ab initio avenues were the only option. If this is not the case and the ADFGY-A program simply displaces applicants from ab initio avenues to itself, and their transfer rate into the Permanent Force is low, then the program will be detrimental to overall recruiting into the Permanent Force in the less popular roles.

The degree to which different employment categories differ in their appeal to prospective candidates is relevant in determining the utility of ADFGY-A as a recruitment tool. In particular, the likelihood of the program making a contribution to overall recruitment outcomes is driven by whether employment categories offered through ADFGY-A are routinely oversubscribed or undersubscribed in the broader ab initio targets. On this basis, the prerequisites for the program to make any real impact on recruitment into the Permanent Force are:

- The employment categories available through ab initio avenues are undersubscribed.

- The ADFGY-A offer increases net total enlistments across all avenues of entry.

- The transfer of Gap Year participants into the Permanent Force is above an established threshold such that the total number of those continuing their service (when all avenues of entry are summed together) is greater than what might have been achieved if there were only an ab initio avenue.[22]

These same prerequisites and conditions can be applied for smaller segments such as the recruitment of women. For example, for the program to make any impact on female representation in the Permanent Force, the number of female applicants must be broadly undersubscribed against targets available through normal ab initio avenues, the ADFGY-A offer must increase the net total female enlistments across all avenues, and the transfer of female Gap Year participants into the Permanent Force at the end of the program, combined with females recruited through ab initio avenues, must be greater than what might have been achieved if there were only an ab initio avenue. On review, it is likely that these three conditions have been met in the 2015 version of the program. Therefore, ADFGY-A has probably made a marginal contribution to improving the representation of women in Army.

At between 8 and 10 per cent of the total Army OR recruiting target (excluding in-service targets), and up to 40 per cent for some employment categories (such as Command Support Clerk), the program competes with ab initio avenues to varying degrees. However, if expanded (either in terms of more employment categories or in terms of total participant targets) the program would likely compete more explicitly with ab initio entry. In this context, it is questionable whether—and to what extent—the program could meet the three prerequisites outlined above. Maintaining two separate avenues of entry that only differ in the length of initial obligation period raises an obvious question concerning the efficacy of having two avenues rather than one. Army may wish to consider a single avenue of entry that either abolishes an obligation period altogether or at least reduces it to be better aligned with the current Gap Year model that has no service obligation.

Overall, it is not possible to conclude that that ADFGY-A contributes to recruitment outcomes in any meaningful way. For those employment categories where ab initio targets are always achieved, the program achieves little or nothing with respect to Army’s recruiting requirements. For those employment categories where targets are not always achieved, it remains unknown whether Gap Year participants would have joined Army through ab initio avenues anyway. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain the recruitment benefit to the Permanent Force that can be attributed to Gap Year. Without knowing how many participants were incentivised to join the Army specifically because of the program, and how many of these participants made a decision to transfer into the Permanent Force, the recruitment benefit of ADFGY-A remains a matter for speculation.

Retention and Ongoing Service

Retention beyond the first year of enlistment is an important measure of success in recruitment efforts as it indicates the extent to which participants who have been trained to the level of a Permanent Force member actually go on to serve in the Permanent Force beyond Gap Year. This is an especially important metric where the program is viewed as an alternative avenue of entry. It has already been observed that transfer rates to the Permanent Force have increased from 32.8 per cent during the previous program to 57.2 per cent during the second. Much of this increase is attributable to the previously mentioned improvements that have facilitated transfer into the Permanent Force, including the ADF’s assurance that a position will be available for those participants wishing to transfer. However, the progress of these participants beyond the first year is of equal, if not more, relevance to an assessment of program success than transfers into the Permanent Force.

While the initial transfer rates are sound, ongoing retention in either the Permanent Force or the Reserves appears to remain an area of weakness. With just 38 per cent of program participants remaining in the Permanent Force after four years of service, and relatively high loss rates after the first and subsequent years, the cost-effectiveness of training and employing participants who do not provide enduring periods of capability after program completion is questionable. Transfer rates into the Reserves do little to offset or compensate for the high loss of numbers in the Permanent Force, because relatively few participants render effective reserve service in subsequent years. Furthermore, transfer into the Standby Reserve (SERCAT 2) appears to be something of a proxy for separation, as 88 per cent of members have not rendered any further effective service of 21 days or more since completing the Gap Year (and most of those who did achieve this level of service had already transferred from SERCAT 2 to SERCAT 5).

Training participants to a relatively high level of capability, including the resources necessary to recruit, train, retain and transfer them, appears suboptimal and fiscally wasteful where their ongoing service and retention is low. This shortfall may represent an area for program review and further assessment by the Army. While this article has not focused closely on the fiscal aspects of the program, an average ADFGY-A participant will cost around $60,000 in salary over the year. This means that the cost of the program is $16 million annually in salaries alone (without including other attributable and non-attributable costs such as allowances, superannuation, housing, training, medical, dental etc.). Failure to realise an investment in the 44 per cent of participants who do not transfer into the Permanent Force represents a poor use of least $7 million of Defence funding annually.

Ongoing Criticism of ADFGY-A

While many positive changes were made to the 2015 program, several criticisms remain. The program’s place in the recruitment landscape remains undefined, a characteristic that owes its origins to the problematic nature of the objectives as either experiential, recruiting or both. It seems apparent from the changes that have been made to the program since its initial inception that Army views ADFGY-A as an alternative avenue of entry; however, Army still has no particular defined expectation or outcome for the program beyond merely meeting the recruiting target and transferring as many as possible into either the Permanent Force or the Reserves. For a multimillion-dollar program, this overly simplistic objective is in desperate need of reform towards a clearer intent.

The program also continues to attract and recruit individuals with relatively high levels of education and aptitude and, due to the limited employment categories available, places them in positions that do not necessarily require these attributes. This situation creates the suboptimal outcome that individuals are not necessarily offered the employment category they are best suited for, are not provided an opportunity to enlist into their most preferred employment category, and are ultimately not employed in roles that make best use of their potential. Furthermore, employment categories that do require the higher aptitude of ADFGY-A participants are denied the applicants they might otherwise have received, simply because their employment category is not part of the ADFGY-A program.

Although ADFGY-A remains extremely popular with candidates and targets are almost always achieved, the program presents potential candidates with multiple options for the same role in a confusing recruitment landscape. The requirement for Defence Force Recruiting to maintain marketing and attraction campaigns for two parallel avenues of entry—Gap Year and ab initio entry—has the effect of splitting resources (or requiring additional resources). It also inevitably places these avenues of entry in direct competition with one another. The efficacy of purposely creating this form of internal competition is questionable, particularly in a situation in which there is no net increase in recruitment, where high-quality candidates are funnelled towards limited roles, and where the only practical difference between programs is whether there is an associated service obligation.

Scope for Improvement

In principle, structural inefficiencies in the design and administration of ADFGY-A are relatively simple to resolve. In the first instance, Army should unambiguously determine whether it intends for ADFGY-A to simply provide an experience for applicants, or whether the program offers a genuine alternative avenue of entry.

If the purpose of the program is predominantly to provide participants with an experience of military life, then there are several changes required. To broaden exposure of Australia’s young demographic to the military, then an expansion exceeding 1,000 each year would be necessary to achieve a tangible and measurable outcome. A specific generalist ‘work experience’ type program that exposes participants to life in the wider Army (rather than life in a specific employment category) would also be necessary. Criteria for participation would need to be reviewed in order to ensure a wide applicant base without compromising normal Army ab initio recruitment avenues. Further, participants should be told not to expect to transfer into the Army at the completion of the Gap Year unless they satisfy Army selection criteria and undertake employment category training. This experiential model would require significant Army resources but would offer a distinct work experience product to a segment of the Australian population that would not normally undertake military service.

By contrast, if the purpose of the program is to provide an alternative avenue of entry to Army, then changes are simpler, but more confronting for Army. To avoid direct competition with normal ab initio avenues of entry, Army will need to consider exclusive ADFGY-A roles (i.e. employment categories where the only avenue of entry is the program). Alternatively, Army may need to reconsider the efficacy of persisting with two avenues of entry to the same employment category where the only substantial difference is the obligation period, or a lack of one. A review would likely indicate efficiencies in either combining the avenues of entry and ceasing or reducing the obligation period to one or two years, or ending the program altogether and reverting to extant obligation periods imposed on ab initio recruits. Consolidation of avenues of entry would simplify the employment offer, remove inequities between individuals recruited through different avenues, allow for focused marketing and attraction approaches, and provide individual applicants with the widest range of employment categories possible to best fit their individual talents, skills, aptitude and preference.

Regardless of the option chosen by Army, the program’s purpose and objectives must be measurable. These performance measures should be more deliberate than simple recruitment and completion outcomes. Measures relating to an experiential objective might include participant satisfaction, positive impact on influencers, increases in participant or public sentiment, increases in Army civilian engagement, improved employment outcomes for participants, and so on. A recruiting objective might consider retention beyond the Gap Year, individual performance, suitability for promotion (and actual promotion), long-term retention, impact on the employment offer and required recruiting targets etc. Whatever the program’s purpose and objectives, performance measurement needs to improve.

CONCLUSION

ADFGY-A has become a mainstay of the Army recruiting landscape. However, as with the program that ran from 2007 to 2012, Army policy and practice perpetuates an uncomfortable ambiguity around the true purpose of ADFGY-A. This is despite its reinvigoration in 2015 and an opportunity to redefine objectives. Just as there were no specific or measurable objectives of the previous program beyond simple recruiting results, there are none for the 2015 program—an unfortunate oversight requiring rectification.

While its purpose requires further definition, there have been significant structural and policy improvements made to the current program. The removal of constraints on participants transferring into the Permanent Force, reduction and consolidation of the number of roles to aid recruiting and management, implementation of a mentoring scheme, and improved general oversight have all greatly enhanced the program. When combined it is likely that these improvements have helped increase the number of participants transferring into the Permanent Force from 32.8 per cent in the original program to over 57 per cent, a marked improvement.

Nevertheless, having made all these improvements, it remains the case that 43 per cent of participants (from the FY 2014–15 to 2020–21 cohorts inclusive) do not transfer into the Permanent Force. Of those who transfer into the Reserves (16 per cent to SERCAT 3/5 and 7 per cent to SERCAT 2), relatively few render a reasonable period of effective service of at least 21 days. The fact that, despite having been trained to a Permanent Force standard and fully exposed to an early Army career and the opportunities and lifestyle it offers, a high proportion of participants are not transferring into the Permanent Force or rendering reserve service suggests that significant inefficiencies in the program persist.

Other criticisms of the program are worth noting: the program dilutes the resources dedicated to marketing and attraction of Army careers, competes with other avenues of entry, results in suboptimal use of the education and aptitude of participants, and generally does not contribute any more to capability than what might be achieved through normal ab initio avenues of entry. For many employment categories where there are no ab initio recruiting problems, the program is unnecessary, suboptimal and a potential waste of resources. Where there are problems in ab initio recruiting it is unclear whether the program helps through transfer of participants into the Permanent Force after their Gap Year, or hinders through siphoning potential ab initio applicants into a competing option with low transfer rates.

Regardless, noting the program’s likely continuation, there are several conceptual changes that Army may wish to consider. First, Army should formally decide on the purpose of program and reflect this clearly in policy, promotional material and career management activities with associated performance measures. Second, the selective nature of the program should be reviewed to permit greater alignment between the aptitude, ability and role preferences of applicants. Third, assuming that the true purpose of the program is to provide an alternative avenue of entry, Army may wish to reconsider the efficacy of offering parallel and competing avenues of entry that differ only in an initial obligation period. Consolidation of all avenues of entry with just one (or no) common obligation period is likely to yield process efficiencies and simplify the employment offer.

Without these changes the ADFGY-A program will remain a confused hybrid scheme stuck in policy and purpose somewhere between an experiential youth program and a recruitment initiative. Currently, it succeeds in being neither.

About the Author

Colonel Phillip Hoglin graduated from RMC in 1994, having completed a Bachelor of Science (Honours) majoring in statistics. In 2004, he completed a Master of Science in Management through the United States Naval Postgraduate School. He graduated from the Command and General Staff College of the Armed Forces of the Philippines in 2006, and was awarded a Master of Philosophy (Statistics) through the University of New South Wales in 2012. He has been involved in workforce analysis since 2004, was the Director of Military People Policy from 2014 to 2017 and the Director of Military Recruiting from 2018 to mid-2020, and is currently a researcher within Defence People Group.

Endnotes

[1] Phillip J Hoglin, 2020, ‘The Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army Program: Real or Rhetorical Success?’, Australian Army Journal XVI, no. 1: 146–166.

[2] As the program is ongoing, this figure represents the total other ranks enlisted into Gap Year between January 2015 and June 2022 inclusive.

[3] A small number (30) of Officer Gap Year participants were appointed each year from January 2018 to January 2021; however, the program is different in structure and outcome such that officer data cannot be combined with that of other ranks.

[4] Since 2012 it has been increasingly common to refer to the Australian Regular Army as the Permanent Force and Service Category 6 or 7; the Army Reserve as Service Category 3, 4 or 5; and the Standby Reserve as Service Category 2.

[5] For example, see Department of Defence, 2008, Defence Instructions (General) Personnel 05-10 Australian Defence Force Gap Year (Canberra); and Department of Defence, 2008, Defence Instructions (Army) Personnel 34-13 Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army Management, Policy and Procedures (Canberra).

[6] Brendan Nelson, Minister for Defence, ‘Get Ready for the ADF Gap Year’, media release, 9 August 2007.

[7] Nathan Church, 2014, The Evolution of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year Program, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library), at: http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1314/ADFGapYear

[8] Department of Defence, Military Personnel Policy Manual (MILPERSMAN) Part 2, Chapter 6, Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army (Canberra), 1 and 13; this replaced Department of Defence, 2008, Defence Instructions (Army) Personnel 34-13, 1.

[9] See ‘Discover Your Path in an ADF Gap Year’, DefenceJobs, accessed 22 April 2022, at: https://www.defencejobs.gov.au/students-and-education/gap-year?

[10] In additional to normal selection requirements, ADFGY-A applicants must complete year 12, be aged between 18 and 24 at enlistment and obtain a competitive aptitude score normally higher than that required for general ADF entry.

[11] Commencing in 2022, recruits apply for and are enlisted into either a generic combat segment or a support segment. These recruits commence basic training as ECN500 prior to allocation to a combat or support employment category towards the end of basic training.

[12] For further explanation of service categories and options, see Department of Defence, 2020, MILPERSMAN Part 2, Chapter 5, Australian Defence Force Total Workforce System—Service Spectrum, AL13 (Canberra).

[13] Some employment category names have changed over the period. The most recent equivalent employment category name is reported.

[14] In this context, combat roles are defined as Infantry Soldier, Artillery Gunner, Operator Air and Missile Defence Systems, and Combat Engineer.

[15] As at 1 April 2022.

[16] Although the title is ‘Gap Year’, participants since 2015 have generally undertaken an 11-month program. The program is sufficiently flexible that extensions are relatively routine for administrative reasons, such as injury, and decreases are also not uncommon where individuals request early transfer into the Permanent Force (indeed, during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large proportion of the 2019 cohort had their Gap Year shortened to enable transition into the Permanent Force or Reserves earlier than the normal 11 months).

[17] This can be due to a range of reasons including self-selection, training failure and poor job-fit outcomes.

[18] Analysis of retention over shorter periods, such as 12 months after the nominal completion of the program, is possible but comparisons against other avenues of entry are less valid.

[19] These figures differ slightly from those provided in Table 3 as they only reflect four of the eight cohorts, whereas the table provides data for all cohorts up to FY 2021–22 (inclusive).

[20] A duration of four years is chosen for comparison as it represents a normal service obligation period for those recruited through ab initio avenues into the same employment categories that are available through Gap Year.

[21] Noetic Solutions, 2010, Evaluation of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year Program, prepared for the People Strategies and Policy Group (Canberra: Department of Defence).

[22] This threshold will vary for each employment category and will require calculation by workforce modellers