Abstract

The first version of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army (ADFGY-A) program, which ran between 2007 and 2012, aimed to develop a pool of willing applicants who would extend their commitment to the Army.1 Although it has often been cited as a success, when the quantitative outcomes are reviewed more closely the extent of its success becomes somewhat ambiguous and largely dependent on views on the ADFGY-A program’s purpose. Despite the possibility that some intangible and immeasurable objectives were achieved, such as attributable changes in community perceptions towards the Australian Defence Force, less than one-third of the participants eventually entered the Australian Regular Army (ARA) during or after the program, and six years later only one in five remained. This low transfer rate and ongoing separation rate suggests that, if success is defined as the proportion of participants who transferred into the ARA, the ADFGY-A program represents a costly and inefficient alternative avenue of entry.

Introduction

In 2006 and 2007, the unemployment rate was low, the economy was performing well and there was relative political and leadership stability. Despite the low unemployment rate, which stood at around 4.3 per cent2 for the national rate and 9.0 per cent3 for youth in early 2007, programs such as Work for the Dole continued to be considered for expansion alongside various youth employment initiatives and a consistent, although small, voice for some type of national service. Concurrently, recruitment into the Australian Defence Force (ADF) had been experiencing long-term underperformance at a time when Army required growth through its Hardened and Networked Army (HNA) and Enhanced Land Force (ELF) programs. In both financial years 2005–06 and 2006-07, just 84 per cent of the recruiting target for the permanent force had been obtained.4 In this national context, and in the lead-up to the 2007 federal election, the Australian coalition government announced the Australian Defence Force Gap Year (ADFGY5)—a program that would continue after the election victory of the Labor Party.

There have since been two ADFGY programs. The first ran from 2007 to 2012 and there were 1630 Army participants before it was ceased.6 The second program commenced in 2015 and is ongoing. Although there were changes in the way the program was managed and the opportunities that were available for continued service after completion, they were otherwise very similar in terms of structure and the range of employment categories (job roles) available to participants.

This article will focus specifically on the outcomes of the 2007–2012 program. As it has now been over 13 years since the first cohort commenced their ADFGY, and eight years since the final 2012 cohort commenced, all participants have had an opportunity to complete ADFGY, transition to the Australian Regular Army (ARA) or Army Reserves (ARes), complete any initial service obligation period and continue to serve voluntarily. This also means that sufficient longitudinal data now exists with which to conduct a quantitative analysis to facilitate a broader and more factual discussion on the actual outcomes of the entire 2007–2012 program.

This article will focus primarily on examining the ADFGY completion rate and subsequent transfer into the ARA and ARes.7 In doing so, this article also aims to moderate some public statements proclaiming the program a success that were made well before any reasonable period had elapsed that would normally allow for a balanced evaluation to be conducted.8 To establish the contextual scene, this article will review the original aims of the program as defined by the ADF and Army, along with previous research and public comments. This is followed by an outline of the workforce climate at the start of the program to help explain why particular decisions were made and the impact these have since had on analysis. Finally, the analysis methodology and results relating to Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army (ADFGY-A) participation and retention are detailed.9 This article will not cover attitudinal aspects of ADFGY, as this is detailed separately in other reports.10

The ADFGY Program

Incorporated into the Recruitment and Retention (R2) Program in 2007 as part of the Howard government’s broad range of initiatives to improve the ADF’s recruiting and retention,11 ADFGY offered ‘an opportunity for young adults to experience military training and lifestyle within a 12-month program’.12 The program was intended to appeal to a slightly different and narrower recruiting demographic than the traditional ADF candidate through the deliberate targeting of young post-secondary men and women because a shorter commitment was thought to reduce a barrier to enlistment for that group. Most notably, there was no compulsion to continue to serve in the ADF after completion of the program’s 12-month period and there was no expectation that participants would choose to do so.13

Other differences between the program and normal ADF service included the education, aptitude and age requirements of participants. ADFGY applicants had to have completed year 12, be aged between 17 and 24 and obtained an aptitude score higher than that required for normal ADF entry. These requirements ensured that participants were of the same demographic as those who might normally undertake a tertiary gap year.14 The first Army participants commenced the program in November 2007 and the last participants commenced in April 2012.15

From the program’s inception, the Defence-wide objectives of ADFGY were non-specific and tended to oscillate from experiential outcomes to recruiting objectives. Subsequently, when the Defence-wide objectives were distilled into Army’s own, several subtle differences emerged such that Army’s objectives did not completely correspond with those of the ADF. Although these were not in direct conflict, there were enough differences to create ambiguity with respect to defining success for the ADFGY.

ADF’s aim for the ADFGY program was formally outlined in the 2008 release of DI(G) PERS 5–10 Australian Defence Force Gap Year.16 The document detailed that the ‘aim of the ADFGY is to provide young men and women with a meaningful experience that allows them to gain a better understanding of the opportunities available to them in the ADF’.17 Similarly, the ADF Retention and Recruitment Strategy Implementation Plan (2007) outlined that the program was to ‘allow young Australians to better understand the opportunities available to them in the ADF, with a potential benefit of increased recruitment’.18 Publicly, the program was marketed by Defence Force Recruiting (DFR) as a ‘try before you buy’ experience to ‘gain the skills and experiences to get ahead in the 21st Century’.19

The aim and marketing statements suggested that the ADFGY was only partially intended as a recruiting avenue for the ADF, as it also emphasised its experiential objective.20 On the one hand, the directive explained that the ADFGY is ‘one of a number of initiatives developed to assist with improving the recruitment and retention of personnel within the Australian Defence Force’ and on the other it was occasionally reinforced that no recruiting outcome was intended.21 This gave rise to potential ambiguity in the true program objectives and subsequent performance indicators.22

Army’s internal aim for the program was outlined in DI(A) PERS 34–13 Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army Management, Policy and Procedures. In contrast with the ADF policy, Army’s main objective was unambiguous: ‘The Army’s objective is to develop a pool of willing applicants who wish to extend their commitment to the ARA or Army Reserves after or during the initial year of service’.23 In other words, from Army’s perspective, the program was ‘about the Army being an employer of choice and providing training and lifestyle experiences for young people’.24 The Army document even specified that the program was ‘a contemporary pathway into the Australian Army’.25

Superficially, there is no particular conflict between the dual aim of providing youth an opportunity to experience military service and providing an additional method of entry into the ADF. However, a misalignment in the definition of success can arise where success for the experiential objective does not necessarily represent success in terms of a recruiting outcome. Conceptually it was quite possible for individuals to have a positive experience but not extend their service, in which case a measure of success from the ADF perspective might not directly translate into a success for Army.

Defining Success

Although there were objectives, the expected performance outcomes or indicators were not developed until well after ADFGY started. It is unclear whether this was through a lack of expectation for the program from which to develop outcomes, through genuine oversight or through lack of guidance from ADF leadership. However, no evidence was found during the research that supports a conclusion that performance indicators were even a basic consideration during development of the program. Ultimately, this is reflected in the understanding that neither the ADF nor Army had any particular defined expectation or planned outcome for the program beyond merely meeting the ADFGY recruiting target. This resulted in success metrics being developed after the program had already commenced.

Metrics and performance indicators for the program were progressively developed during the first two years. By this time the Air Force gap year program was being scaled back, Navy had significantly reduced its target and Army’s program had been reduced due to situational factors that will be described later. The only departmental review of ADFGY, conducted in 2010, implied that there was still no formal view of what constituted success of the program; instead, a definition had to be derived (‘synthesised’) by the authors of other documents.26 Subsequently, the review determined:

[It would] examine the ADF Gap Year Program’s potential to benefit the ADF through:

- Participants transferring into the Permanent or Reserve forces either during or immediately on completion of their ADF Gap Year service.

- Creating a cadre of ‘ambassadors’ for ADF careers, additional to those already existing in the Permanent and Reserve Forces.

- Accessing demographic groups that would not normally consider military career options.

- Providing ‘test bed’ opportunities for new approaches to recruitment and training’.27

In other words, the review adopted a broad definition of success relating to an opportunity for youth to experience military service and subsequent recruiting into the ADF. At the time of its publication, the review had only one cohort of participants from which to make observations and limited longitudinal data to assess recruiting and retention outcomes; it was therefore constrained in making observations relating to some success metrics. To address the absence of empirical evidence that existed at the time of the review and to fill a gap in knowledge about the eventual outcomes, this article defines success more narrowly in terms of the results for recruiting and continued service in either the permanent or reserve forces after participation in the program.28

Previous Findings

Within the first 12 months of the program a perception arose that ADFGY was a success.29 This view could only have resulted from assessment against the experiential objective because, in reality, insufficient time had elapsed since the commencement of the program to make an assessment against any other objective. Unfortunately, the numerous media reports claiming success, fed by often repeated and inappropriate statistics that did not actually demonstrate success, are likely to have contributed to an unbalanced and unchecked public perception that the program was a success.

Departmental Review

The 2010 departmental review possibly contributed to some of the prevailing misperceptions of the program’s success. Aside from some findings relating to the intangible successes of the program, the review made findings that ‘The ADF Gap Year appears to have provided additional recruitment potential to the ADF via transfers from the ADF Gap Year Program to the Permanent Forces and Reserves’ and that ‘The ADF Gap Year Program has successfully attracted females to the ADF’.30 While these statements have a strong prima facie appeal given the limited data available at the time (just one full cohort), the report did not consider many other factors, discussed later, that give rise to these assertions being challenged.

Unfortunately, the assessments made by the departmental review infiltrated much of the ensuing public narrative about the program’s success without the opportunity for sensible discourse surrounding the quantitative aspects of the program. Ultimately, and in contradiction of some of the review’s findings, the program was closed because it was viewed as unnecessary for recruiting and added an unnecessary burden on the training system given the proportion of participants that eventually transferred into the permanent forces.

Media Reporting

Perhaps capitalising on the 2010 departmental review, most of the media articles about the program espoused its success based on the attractiveness of the program to year 12 graduates and their ability to fill the available ADFGY opportunities. For example, in December 2007, just one month after the first participants had started ADFGY, newspapers were reporting that the program was a ‘huge success’. 31 The use of this one-dimensional definition of success risked the program being labelled as such when the reality was less clear. Unfortunately, after media reports and articles are published in the public domain, it becomes difficult to moderate public perception, particularly that which is held within the ADF. It is fair to suggest that, shortly after the launch of the program and as a result of media reporting, the public perception of the program had already been entrenched and any real analysis would have been unlikely to change the prevailing views, even in the presence of evidence.152

Situational Factors

The claims of success of the ADFGY program that permeated through the media and were supported by the departmental review were at best premature and did not consider many of the situational factors that influenced ADFGY throughout its duration. Had more time been taken and situational factors considered, many of the conclusions and findings may have been quite different. Throughout its duration, the ADFGY-A program was constrained by a number of influences. The capacity of DFR and Army training establishments to recruit and then train participants represented just two of the more practical constraints on the numbers that could be accepted into the program. Accommodation, facilities, training duration, course scheduling and other considerations provided further limitations on the number of candidates that could be accepted.

However, there were two factors that placed very specific pressures on the program. First, Army changed its force structure and, second, it over-achieved on its own retention goals. These factors created internal pressure to reduce ADFGY-A recruiting targets and constrained both the employment categories available to participants and the ability to transfer into the ARA on completion of the program. Furthermore, these constraints were inconsistent and varied throughout the program’s duration, making comparisons between cohorts problematic and thereby confounding any analysis.

When the ADFGY commenced in 2007, it was expected that the total target would remain around 500 eventual recruits, with targets for each employment category relatively consistent from one year to the next. However, a program to increase Army’s strength, announced in 2007 as the ELF/HNA, changed this expectation. While unintended, the need to recruit and train additional ARA personnel had four key detrimental impacts on ADFGY-A, including:

- a reduction in ADFGY-A recruiting opportunities, decreasing from 500 in financial year 2007–08 to 317 in the following financial year, partly due to a loss of training positions

- a reduction in opportunities to transfer into the ARA due to a lack of available positions that were now taken up by the HNA increase

- a reduction in the number of targets for the popular ADFGY-A role of Infantry Soldier, due to the heavy growth in ARA Infantry Soldier for the HNA recruiting that consumed infantry training positions

- the allocation of General Enlistment ADFGY-A participants toward employment categories that they may not have otherwise chosen.

The requirement for growth in Army also necessitated the commencement of the R2 Program and other favourable changes in conditions of service. These changes resulted in a dramatic decrease in separation rates that, when combined with the increased ARA recruiting achievement, further limited opportunities for transfers into the ARA from ADFGY. Although opportunities for transfer still existed, they were significantly constrained to just a few employment categories where the recruiting targets were not already being met and where vacancies existed.

Finally, workforce funding had a significant impact on the program. Unlike most funding for military personnel, ADFGY was funded under neutral arrangements—that is, it did not come from Army’s bottom line and was funded separately. Although this meant there was no funding risk for Army in increasing or decreasing participation in the program, there were very significant pressures rising from over-retention elsewhere within the ARA. Army had started to exceed its personnel funding—a problem that first arose in 2009 and then became significant in 2010—which presented a significant problem. Strength became intensively managed and any initiative that increased strength beyond Army’s funding was closely scrutinised. As a result, the ADFGY-A program was progressively wound down and its funding was eventually used in support of the burgeoning ARA workforce.32

The effect of changes in force structure, recruiting and retention initiatives, and funding on the program should not be understated. These factors, which existed at varying stages and degrees throughout the program’s duration from 2007 to 2012, collectively distort and confound any analysis of the program. It is unfortunate and detrimental to the historical record that reporting to date has not given an appropriate level of consideration to these factors. Nonetheless, Army’s ability to conduct the ADFGY-A will remain subject to the effects of structural changes, workforce initiatives and funding, which suggests that such a program can unnecessarily burden an already complicated Army workforce planning system.

Data and Methodology

ADFGY participants were specifically recorded and identified in Defence’s human resource system as their own ‘service type’. This allowed all participants to be identified and accurately tracked throughout their time in the program along with any subsequent service in the ARA, ARes or Standby Reserve (SRes). For this analysis, data fields obtained included the ADFGY enlistment date, employment category, gender, separation or transfer date, and any subsequent movements into the ARA, ARes, SRes, or other Service. Using the data available, and with respect to the purpose of ADFGY mentioned earlier, analysis of the program was approached from three perspectives:

- achievement of ADFGY-A recruiting targets

- completion of ADFGY-A and/or transfer into the ARA or ARes

- retention of those ADFGY-A participants who had transferred into ARA or ARes.

Results

The key statistics relating to the program and subsequent service are relatively simple to ascertain but have not previously been released for wide distribution. There has been no final report of the 2007–2012 version of ADFGY-A and the figures concerning recruiting results, completion outcomes and ongoing service have not been previously published in any form. This section will detail the known figures on recruiting results and retention of ADFGY-A participants.

Recruiting Outcomes

As highlighted in many media articles and the departmental review, recruitment into the ADFGY was successful, with most targets achieved.33 This was exhibited through not just the achievement of the target for recruitment directly into an employment category but also the achievement of the target for recruitment into a generic, non-specific category known as General Enlistment (GE), where participants would later be allocated to a specific employment category during training. Table 1 shows the recruiting targets for each financial year along with the totals recruited into each employment category before and after allocation of GE participants to a certain category.

Table 1. ADFGY-A recruiting targets and achievement

| Employment Category (EC) | Target | Achievement | ||||||

| 2007–08 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | Total target | Recruited EC | Allocated EC | |

| Dispatcher Air (ECN 099) | 2 | |||||||

| Artillery Gunner (ECN 162) | 13 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 108 | 110 | 179 |

| Artillery Command Systems Operator (ECN 254) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Cavalryman (ECN 063) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 14 | 14 | 32 | ||

| Clerk Finance (ECN 076) | 2 | |||||||

| Combat Engineer (ECN 096) | 5 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 38 | 38 | 46 | |

| Cook (ECN 084) | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Dental Assistant (ECN 029) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 8 | |

| Driver (ECN 109) | 10 | 10 | 35 | 10 | 65 | 65 | 111 | |

| Ground Based Air Defence (ECN 237) | 10 | 12 | 21 | 21 | 19 | 83 | 75 | 81 |

| Operator Administration (ECN 074) | 14 | 30 | 31 | 51 | 34 | 160 | 132 | 165 |

| Operator Catering (ECN 363) | 17 | 12 | 10 | 15 | 54 | 42 | 48 | |

| Operator Movements (ECN 035) | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 21 | 22 | 21 |

| Operator Petroleum (ECN 269) | 3 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 10 | |||

| Operator Radar (ECN 271) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 9 | ||

| Operator Unmanned Aerial System (ECN 250) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 11 | |

| Operator Supply (ECN 294) | 22 | 35 | 34 | 71 | 41 | 203 | 193 | 238 |

| Rifleman (ECN 343) | 192 | 85 | 76 | 76 | 56 | 485 | 498 | 613 |

| Signaller Combat (ECN 660) | 1 | |||||||

| Tank Crewman (ECN 065) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Technician Preventative Medicine (ECN 322) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Marine Specialist (ECN 218) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Medical Operator (ECN 031) | 2 | |||||||

| General Enlistment (ECN 500)* | 215 | 80 | 82 | 377 | 390 | 37** | ||

| Total | 500 | 317 | 315 | 315 | 220 | 1,667 | 1,630 | 1,630 |

The data suggest that there was little difficulty in reaching the ADFGY recruiting targets, with a final recruiting result of 98 per cent.34 The program remained popular with applicants throughout the entire period of 2007– 2012 and it was normal for DFR to receive far more applications than there were positions for most employment categories. This most likely reflected the positive ‘employment value proposition’ that provided successful applicants with training, salary and experiences with a limited obligation period of just one year. What remains unclear is the extent to which the program attracted applicants who would not otherwise have considered an Army career, whether it was a competing product alongside the usual ab initio avenue of entry for the same candidates, whether it attracted a group of marginal applicants who were uncertain about an Army career and were therefore at a higher risk of leaving during or immediately after the program, or whether a combination of all of these factors contributed to success ambiguity. While this will be discussed later, what has emerged is that, unless success is defined as an opportunity to experience military training and lifestyle, recruiting success alone is most likely a poor metric for overall program success and perhaps retention beyond the ADFGY might have been more appropriate.

Regardless, because of its popularity among applicants, it can be safely assumed that a larger overall ADFGY target could have been achieved; however, the effect on the training system and facilities would have been significant and prohibitive. If the program were expanded, it is likely that the usual ab initio target would have required a reduction in order to accommodate the additional ADFGY participants. As it turned out, the situational factors detailed earlier actually necessitated increases in the usual ab initio intake, which, due to facilities constraints, necessitated a decrease rather than an increase in ADFGY-A targets. This decision tacitly acknowledged the importance of sustained recruiting of people who have a longer service obligation period, rather than one year, for the provision of capability.

Completion of ADFGY-A and Transfer into the ARA and ARes

Perhaps the most under-reported metric concerning ADFGY-A is that over one-third (35.2 per cent) of the participants did not continue into either the ARA or ARes.35 Precise reasons for this cannot be determined purely from the available data, but some possibilities include self-realisation of a poor job fit with Army (self-selection), a marginal propensity to join or affinity for Army in the first place, lack of desire for further immediate service after fulfilment of the 12-month obligation, or a perceived lack of opportunity in Army after the program. Interpretation of a 35.2 per cent loss rate as a good, a bad or an indifferent outcome will depend on whether success is viewed as providing an experience or providing additional recruits into the permanent or reserve force. If it is the latter then, arguably, losing over one-third of all participants can only be viewed as a loss of opportunity and resources.

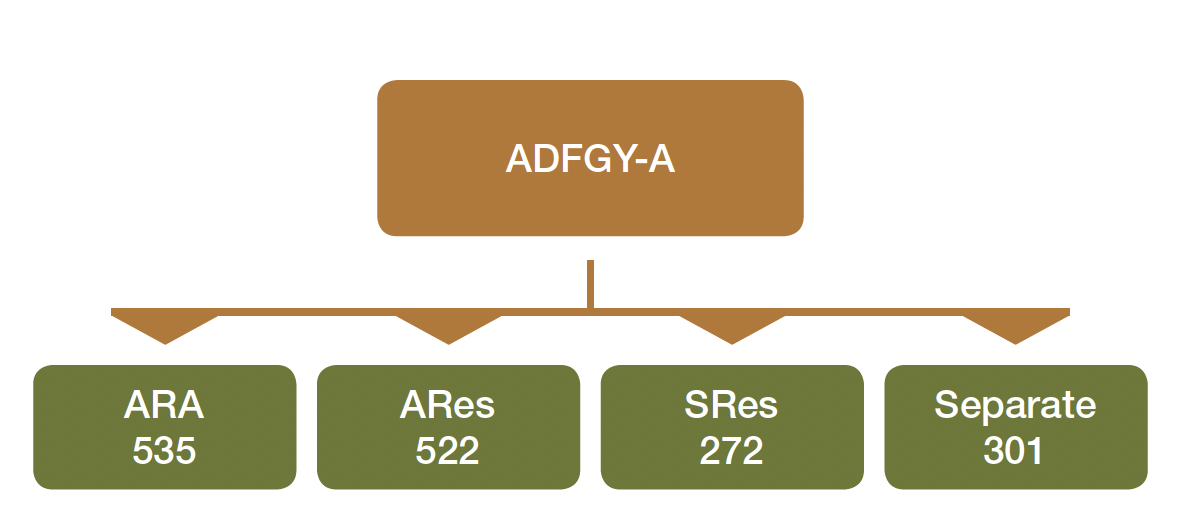

Figure 1 and Table 2 show where ADFGY-A participants transferred immediately after completion of the program or during the program itself. By the end of the program, 32.8 per cent had transferred to the ARA, 32.0 per cent had transferred to the ARes and the remaining 35.2 per cent had either separated or remained in the SRes. Differences between male, female and different employment categories are likely to reflect the varying constraints on transferring into the ARA rather than a characteristic of gender. Specifically, many of the male-dominated employment categories had limited opportunity for transfer into the ARA, which was not the case in employment categories where women were participants. This had consequences for the transfer rate from combat employment categories, where only 26.5 per cent eventually transferred into the ARA compared with a transfer rate of 42.4 per cent into combat services support (CSS) employment categories.

Table 2. Transfer of ADFGY-A participants

| ARA | ARes | SRes/ separation | Total | |

| Total* | 535 (32.8%) | 522 (32.0%) | 573 (35.2%) | 1630 |

| Combat | 235 (26.5%) | 314 (35.4%) | 337 (38.0%) | 886 |

| CSS | 300 (42.4%) | 207 (29.3%) | 200 (15.4%) | 707 |

| Males | 354 (28.2%) | 418 (33.3%) | 482 (38.4%) | 1254 |

| Females | 181 (48.1%) | 104 (27.7%) | 91 (24.2%) | 376 |

* Thirty-seven General Enlistment participants of the 1,630 were not allocated to an employment category.

ADFGY-A = Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army; ARA = Australian Regular Army; ARes = Army Reserves; SRes = Standby Reserve; CSS = combat services support.

ADFGY-A = Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army; ARA = Australian Regular Army; ARes = Army Reserves; SRes = Standby Reserve.

Figure 1. Transfer and separation of participants after ADFGY-A

Publicly reported results initially suggested that ADFGY-A might have been particularly successful for the recruiting of women,36 with almost half (48 per cent) of the 376 women transferring into the ARA, an outcome that was substantially larger than that for male participants (28 per cent). However, in survey responses, one-third of the starting number of women indicated they would have joined the ARA anyway, which means that over the five-year duration of the program as few as 75 additional women entered the ARA.37 Therefore, ADFGY-A was only a marginal initiative in attracting women into Army and would probably be insufficient to justify the program on the basis of diversity outcomes alone.

Speculatively, had situational factors and constraints on transfer into the ARA not existed, it is possible that the combined transfer rate into the ARA for male and female participants could have exceeded 50 per cent. Even if this figure was realised, the loss of participants of somewhere between the observed figure of 32 per cent and a speculative figure of 50 per cent within a year, most of whom were fully trained at the time of their separation, represents a costly avenue of entry into the ARA and a costly experiential opportunity for those who did not go on to provide further service in the Army. The ADFGY-A cost around $66 million38 in salaries alone, which means that up to $44 million was paid in salaries for people who would not go on to provide any full-time capability (or, alternatively, the apportioned cost for every ADFGY-A participant who transferred into the ARA was three times greater than a person who was recruited directly into the ARA without going through ADFGY-A).

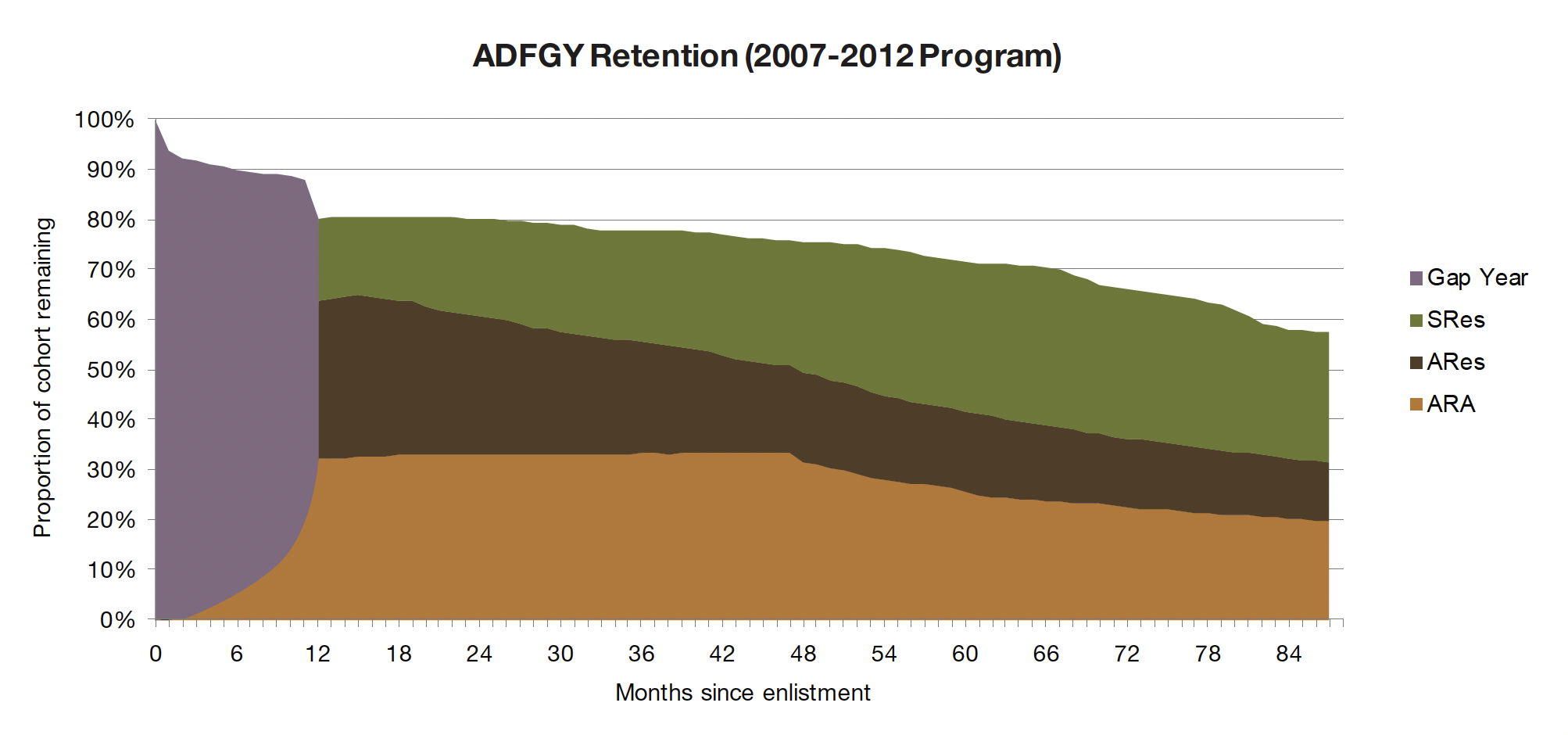

Retention of ADFGY-A Participants in the ARA and ARes

Initial transfer rates provide only part of the interpretation and sufficient time has now elapsed for a longitudinal analysis of the entire 2007–2012 program. This is because all participants have completed the ADFGY, made decisions to transfer to the ARA or ARes and have been able to complete any obligation period that they may have been required to complete when they transferred.

One of the most significant behavioural observations after the 48-month mark, shown in Figure 2, is that the separation of former ADFGY participants partially mimicked the same surge in separation behaviour exhibited by the ARA after the four-year initial period of service, with 21.8 per cent of those who completed their fourth year separating in the fifth. This indicates that the 32.8 per cent of participants who transferred into the ARA were not substantially more likely to maintain a career beyond their initial obligation period in the ARA than their ab initio counterparts. This debunks a view that the ADFGY-A participants who transferred into the ARA were somehow more committed after having being exposed to a ‘try-before-you-buy’ opportunity.39

Cumulatively, one in three participants (32.8 per cent) transferred into the ARA, one in four (26.3 per cent) completed a fifth year, and one in five (20.5 per cent) remained after just seven years. This observation challenges the view that ADFGY-A was a success because not only did less than one-third transfer into the ARA but also those who did exhibited separation behaviour similar to normal ab initio recruits. Furthermore, it introduces the possibility that if the program drew applicants away from the ARA then it may actually have been detrimental, rather than beneficial, to Army. Survey data of the first cohort indicates that 47 per cent of male participants would have joined the ARA in the absence of ADFGY-A, but only 28 per cent did.40 If extrapolated through the whole program (1,254 male participants), the competition between ADFGY-A and normal ab initio entry may actually have resulted in the loss of around 230 male participants who might otherwise have joined the ARA.

Unfortunately, the ARes did not fare any better. While 32.0 per cent (522) of participants transferred directly into the active ARes, only one-third of those (181), or just 11 per cent of the original ADFGY cohort, were still in the active ARes four years after they finished program. This proportion has since increased to 16 per cent through transfers of ADFGY participants into the ARes who initially transferred into the ARA.

Overall, just four years after their participation in ADFGY-A (five years of total service), only 26.3 per cent of the original cohort were in the ARA and just 16.0 per cent were in the active ARes. Another two years later, or six years after their participation in ADFGY (seven years of total service), the retention had further degraded to just 20.5 per cent in the ARA and 12.2 per cent in the active ARes. This means that, after their service in ADFGY-A and subsequent transfer into the ARA and/or ARes for a period of six years, less than one-third of the total number of ADFGY-A participants were serving in any capacity, or, conversely, two-thirds were not providing any capability whatsoever in any capacity.

ADFGY = Australian Defence Force Gap Year; ARA = Australian Regular Army; ARes = Army Reserves; SRes = Standby Reserves.

Figure 2. Retention of ADFGY-A 2007–08 and 2008–09 participants

Discussion

Was the ADFGY Program a Success?

An assessment of the ADFGY’s success depends primarily on the criteria by which success is defined. As discussed earlier, the actual definitions of success varied and were not necessarily complementary. I argue that, if experiential objectives are set aside, the transfer rate of just 32.8 per cent of fully trained personnel into the ARA, of which 21.8 per cent separated in their fifth year, represents an ineffective and costly avenue of entry regardless of the attractiveness of the program to applicants. This loss rate is not sufficiently offset by the 32.0 per cent of participants who transferred directly into ARes, where fewer than half remained at the end of five years of total service. Additionally, the possibility that ADFGY-A had a detrimental impact on the normal ab initio avenue of entry through a competing rather than complementing offer cannot be discounted. This means that if success is defined as those participants willing to transfer into the ARA or ARes then, from a numerical perspective, it was at best questionable and at worst unsuccessful.

However, it remains a valid assessment that some of the intangible benefits of the program may have been realised. There is evidence from internal reporting and the departmental review that the participants themselves were satisfied with the program, and the ‘try before you buy’ approach attracted a wide range of applicants. It is possible that individuals subsequently took their positive experiences of military service into the broader community, which may have had benefit for the nation and the ADF. Unfortunately, the extent to which this occurred has not been the subject of research (which is increasingly difficult given the passage of time), so, for now, qualitative measures of success against the experiential objectives must remain the subject of speculation.

How the Message of Success Became Compromised

Given the speed at which the ADFGY was publicly announced as a success before a cohort had even finished one year, moderating and providing a ground truth for this perception was always going to be difficult, even when data became available. This was not helped by the absence of a robust definition of success, which allowed for wide flexibility in what could be termed successful. The haste to announce policy success, overlayed with no clear definition for it, conspired to compromise any sensible discussion concerning the real outcomes of the program and make the perception of success almost irreversible, whether it was correct or not.

This observation highlights a potential risk for Army personnel policy, where there is sometimes a conflict between the time it takes to record the outcomes accurately and the pressure to make positive public announcements. This is particularly problematic if it turns out that an earlier announcement may be at odds with an emerging reality, as may have been the case with ADFGY. Typically, the Department of Defence does not have a strong appetite for correcting, withdrawing or retracting previous assessments and announcements unless there is a reason to do so, especially if some (but not all) objectives were achieved. Unfortunately, this reluctance does little more than perpetuate potentially false views of a particular policy.

Lessons for Future Personnel Policy

One of many of the harsh realities of personnel policy analysis is that it is very rare that outcomes can be observed and measured in a short time frame. In the case of the ADFGY, a complete review had to wait until the last participant from 2012 had completed their service obligation period. By then, any findings of a review may only be relevant as an historical artefact because, as is the case, the ADF embarked on a second version of the program without a review of the first.

The generic risk for Army is that an incomplete analysis of a policy or program can threaten the sound development of evidence-based policy on other related topics, such as reductions in service obligation periods (for example, Army’s one-year Initial Minimum Period of Service trial). Although a balance may be required between early evidence of success versus a more complete analysis, this only amplifies the necessity for robust definitions and associated metrics from the start. There are several lessons arising from the ADFGY-A program that are relevant for future personnel policy initiatives. First, the aim and objectives should be consistent and unambiguous between policy documents. Second, metrics must be developed for each objective and must be specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely. Third, interim or preliminary measures of success should be defined and associated with the long-term objectives. Fourth, preliminary announcements of success should always be moderated and should never restrict the subsequent announcements of revised and updated information. Fifth, the organisation with responsibility for analysis and reporting should be centralised and intimately involved in policy metric development. Finally, outcomes of personnel policy initiatives will rarely be evident within 12 months and this fact should prevail in discourse, reporting and analysis.

Conclusion

The ADFGY-A program has widely been considered a success, particularly in attracting personnel who might not have otherwise considered an Army career. However, although there may have been constraints on personnel transferring into the ARA, particularly male participants, less than one-third of all participants eventually chose to do so. The fact that participants were trained to an ARA standard and had been fully exposed to an early ARA career but still separated at such high rates provides strong evidence that the program was an ineffective and costly avenue of entry. This finding draws into question the common perception of the 2007–2012 ADFGY-A as a success and the rationale behind its reintroduction in 2015.

Perpetuation of the view that the program was successful has much to do with the ambiguous aims and objectives that various policy documents had for the program. The fact that there were no specific or measurable objectives or performance indicators did little to help the situation. This alone constituted a significant oversight in policy development and represents one of the more significant lessons for Army and the broader ADF. Ultimately, if Army is to be able to identify and capitalise on successful workforce policies, or remediate those that are not successful, an adequate framework of success definitions and metrics must be developed before the policy is implemented.

Endnotes

1 Department of Defence, 2008a, Defence Instruction (Army) Personnel 34-13 Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army Management, Policy and Procedures (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2008a), 2.

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 6202.0—Labour Force, Australia, table 1, Series ID A8442305A, Unemployment Rate: Persons, Seasonally Adjusted.

3 Ibid, table 13, Series ID A84424185C, Unemployment Rate: Persons, Seasonally Adjusted.

4 Department of Defence, 2007, Annual Report 2006–07 (Canberra: Department of Defence), table 4.10, at: https://www.defence.gov.au/AnnualReports/06-07/2006-2007_Defence_ DAR_04_v1_s3.pdf

5 The Australian Defence Force Gap Year (ADFGY) program was initially called the Military Gap Year Scheme (MGYS). This name was changed prior to final release of policy and marketing campaigns to avoid any unintended association through use of the word ‘military’ and ‘scheme’ that might imply conscription.

6 By the time new entries into the ADFGY program closed in 2012 some 2,590 personnel, 1,630 of whom were Army, had participated, with the last completing his ADFGY service in April 2013.

7 Since 2012 it has been increasingly common to refer to the Australian Regular Army as the Permanent Force and Service Category 6 or 7; the Army Reserve as Service Categories 3, 4 or 5; and the Standby Reserve as Service Category 2.

8 Noetic Solutions, 2010a, Evaluation of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year Program (Canberra: Department of Defence).

9 As reports on behavioural aspects of the program have already been released, this article’s scope has been narrowed to examine those measures of success that can be quantitatively and accurately observed and measured.

10 Directorate of Strategic Personnel Policy Research, 2012, Project LASER ADF Gap Year Report 2010/11 and 2011/2012 (Canberra: Department of Defence).

11 Other initiatives, familiar to many currently serving personnel, included the Graded Other Ranks Pay Scale, Army Expansion and Rank Retention Bonus, and Defence Home Owner Assistance Scheme. For a consolidated detail of initiatives, see Noetic Solutions, 2010b, Review of the Australian Defence Force Recruitment and Retention Strategy (Canberra: Department of Defence).

12 Department of Defence, 2008b, Defence Instructions (Army) Personnel 34-13 Australian Defence Force Gap Year—Army Management, Policy and Procedures (Canberra: Department of Defence), 1. A total of 2,590 comprising 633 Navy, 1,630 Army and 327 Air Force (Source: PMKeyS).

13 In fact, in some advertising materials the program was marketed as a ‘try before you buy’ initiative. See, for example, Defence Force Recruiting, 2007a, ADF Gap Year Program, fact sheet (Canberra: Department of Defence). This was emphasised in media—for example, Kerry-Anne Walsh, ‘Join the Army for a Year, Students Urged’, The Age, 15 October 2006, at: http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/join-the-army-for-a-year-students-urged/2006/10/14/1160246371620.html

14 Furthermore, after completion of the program, a financial incentive to return to the ADF within five years after obtaining further education or a certified trade skill was available. Department of Defence, 2008c, Defence Instructions (General) Personnel 05-10 Australian Defence Force Gap Year (Canberra: Department of Defence).

15 Navy and Air Force programs commenced in January 2008. The last Air Force participants commenced in January 2010 and the last Navy participant commenced in June 2011.

16 Department of Defence, 2008c. See also Department of Defence, 2011, Defence Instructions (General) Personnel 05-10 Australian Defence Force Gap Year, Complete Revision, (Canberra: Department of Defence).

17 Department of Defence, 2008c, 1.

18 Department of Defence, 2007, ADF Retention and Recruitment Strategy Implementation Plan (Canberra: Department of Defence).

19 Defence Force Recruiting, 2007.

20 Department of Defence, 2011. Introductory paragraphs 2 and 3 describe the ADFGY as providing experiences within the military.

21 Ibid., 1.

22 A synopsis of the political discussion concerning whether recruiting was an intended aim is in N Church, 2014, The Evolution of the Australian Defence Force Gap Year Program (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia) at: http://www.aph.gov.au/ About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1314/ ADFGapYear. Although the programs of the three Services differed significantly, all three had a longer term aim for participants that included the potential for re-enlistment or continued service.

23 Department of Defence, 2008a, 2.

24 Ibid., 1.

25 Ibid., 1.

26 Noetic Solutions, 2010a, states (at 8): ‘The performance of the ADF Gap Year Program was then evaluated against: objectives synthesised from the R2 Implementation Plan, the relevant Defence Instruction and the Request for Quotation and Tasking Statement’.

27 Ibid., 7.

28 An assessment of success against an experiential objective would require methods such as surveying the participants—an approach that is beyond the scope of this article.

29 For example, see Warren Snowdon, Minister for Defence Science and Personnel, 2008, ‘ADF Gap Year a Resounding Success’, media release, 13 November 2008, at: https:// parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/media/pressrel/OP3S6/upload_binary/op3s60. pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22media/pressrel/OP3S6%22

30 Noetic Solutions, 2010a, 8. The claim of additional recruitment potential made in Noetic Solutions, 2010a, was not made against a benchmark or an expectation of what might have been expected from the program, nor was this balanced against what might have been achieved in the absence of the program. This is an unfortunate oversight of the departmental review.

31 There are many examples, including, ‘Defence Gap Year “Outstanding Success”’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 2007. Also see Australian Defence Association, ADF Gap-Year Program Aimed at the Future, at: http://ada.asn.au/commentary/formal-comment/2007/adf-gap-year-program.h…

32 See reporting in Sean Parnell, ‘Swollen ADF Puts Brakes on Recruiting’, The Australian, 31 May 201. See also Jennifer Crawley, ‘Army Gap Year Misfires’, The Mercury, 4 August 2012; ‘Defence Makes Cuts to Gap-Year Scheme, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 February 2011. Also outlined in Church, 2014.

33 Denis Peters, ‘Army Recruitments Above Target Last Year’, Brisbane Times, 4 January 2008, at: http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/news/national/army-recruitments-above-t…; Jorja Orreal, 2008, ‘Hundreds Sign Up for Taste of Army Life in Gap Year’, The Courier Mail; ‘Defence Declares ADF Gap Year Huge Success, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 November 2008, at: http://news.smh.com. au/national/govt-declares-adf-gap-year-huge-success-20081114-66fm.html

34 Recruitment into the program was aligned roughly with the end of the school year, with the majority of participants joining between January and March and a smaller intake later in the year. The largest number of participants in Army at any one time was 463 in March 2008, shortly after the program’s commencement and when the target was still relatively large. The number of participants declined progressively until April 2013.

35 There is some evidence that initial expectations of the program were not especially high. At the opening of applications for the program in August 2007 the then Minister for Defence, Dr Brendan Nelson, stated ‘Probably half or so will probably leave and not ever come back but there will also be a proportion who we will encourage to come back within five years’. In hindsight, this statement was somewhat more accurate than much of the public discourse that came afterwards. ‘PM Announces Gap-Year Army Program on YouTube’, The Daily Telegraph, 9 August 2007; ‘Prime Minister John Howard’s Defence Gap Year Announcement’ [video], 8 August 2007, at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=rYzxhLCuIuY

36 For example, see ‘Defence Gap Year “Outstanding Success”’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 2007; ‘Recruits Bridge the Gap’, The Daily Advertiser, 31 March 2008, at: http://www.dailyadvertiser.com.au/story/723425/recruits-bridge-the-gap/

37 See Army Supplementary Data to Directorate of Strategic Personnel Policy Research, 2012, Project LASER ADF Gap Year Report 2010/11 and 2011/2012 (Canberra: Department of Defence).

38 In financial year 2012–13 salaries, the salary component for a gap year participant is estimated to be at least $40,500 over the duration of the year. This does not include other allowances such as trainee, service and uniform allowances, and does not factor other benefits such as medical, housing and superannuation.

39 This is despite having had the opportunity to leave without detriment in the first 12 months of ADFGY.

40 Army Supplementary Data to Directorate of Strategic Personnel Policy Research, 2012, Project LASER ADF Gap Year Report 2010/11 and 2011/2012 (Canberra: Department of Defence).