Abstract

The Australian Army is investing a high proportion of its capability in operations, turning to the deployment of reservists to supplement the number of full-time soldiers available to deploy. While demand for Army reservists has increased, total force numbers have been decreasing. Defence-sponsored surveys of serving reservists are designed to analyse their motivation for serving from a quantitative standpoint. This paper presents the findings of doctoral research using a qualitative approach to complement those survey results, seeking to understand the experiences and perspectives of individuals undertaking Reserve service in Australia and the United Kingdom to assist human resource (HR) policy and practice within the Australian Army. The doctoral research involved nine participants who were asked to describe their motivation for joining the Army Reserve, their experience of HR activity, and what they regard as the most enjoyable and least enjoyable aspects of service. This data was analysed to understand individual experiences of Reserve service, retention and resignation to validate prior research. More importantly, this latest research enabled the further development of previous theories and concepts. The study suggests that the motivation of reservists to serve is unique and represents a combination of both volunteer and part-time employee motivation. The conclusions drawn demonstrate that most participant reservists regard their service experience through both a volunteer perspective (value for time) and through an employee perspective (value for money). Reservists’ attitude to their service experience in turn influences the rates of resignation and retention.

Is the nature of ADF Reserve service a form of part-time ADF employment or a unique form of service – or perhaps elements of both?

- Podger, Knox and Roberts1

Introduction

A 2007 review into military superannuation arrangements questioned the unique nature of Australian Defence Force (ADF) Reserve service. The review team argued that the provision of pro-rata full-time ADF conditions of service, including superannuation, is logical if the Reserve is a form of part-time employment. If, however, Reserve service is unique, then unique conditions of service should apply. The review team did not make a specific recommendation on Reserve service, leaving the matter for determination by the Department of Defence.2

Since the early 1990s, Army Reserve numbers have fallen steadily from a level of 24,000 to 25,000, to around 13,500 actively serving members today.3 This has had a significant effect on ADF capability and the quality of Reserve training, the morale of reservists and, consequently, attendance at parade nights and activities. Defence has conducted numerous quantitative surveys of reservists in an attempt to understand their motivations for serving. The recent qualitative research described in this paper is designed to complement that survey work by examining the experiences and perspectives of those undertaking military service in two Army Reserve organisations: the Australian Army Reserve and the United Kingdom’s (UK) Territorial Army.4

This paper addresses the unique nature of Reserve service and also analyses the reasons reservists provide for resignation. Through an overview of existing research, the paper presents the results of the original study designed to record the lived experiences of Australian Army reservists and UK Territorial Army members. The nine participants included serving and ex-serving reservists who reflected on their motivation to join, their experience of recruitment, training, promotion and some of the most and least enjoyable aspects of Reserve service. Ex-service participants provided insights on their reasons for resigning. The participants — both male and female — had varying lengths of service, were from a range of corps, ethnic backgrounds and ranks, and represented a broad diversity of Reserve service. The size of the participant group was based on a convenient sample. The small number used is considered appropriate for the research approach employed. The research approach prefers small group sizes because it allows the researcher to dig deeply into the content and meaning derived from the interviews. This contrasts greatly from large, statistics-based research that requires large numbers of participants and limits the number of possible responses to questions. This study suggests that reservists’ motivation to serve is unique and combines motivations typical of both unpaid volunteer and paid part-time or casual employees.

The study used a human resource (HR) lens to narrow the literature and research. This permitted the exclusion of other aspects such as equipment, facilities and logistic support, allowing the research to be suitably focused. Consequently, the scope of this paper includes a comparison of Reserve service and employment utilising industrial relations definitions. The study found that Reserve service most closely resembles casual employment, although there are significant differences. The ‘part-time’ employee psychological contract begins with the recruiting campaign5 and is extensively discussed in a broad range of Defence literature.6 The inaccuracy of terminology used in Defence literature often affects reservist identity and can cause psychological contract tensions between the Army and its reservists.

This study identifies that many reservists regard their service through both a volunteer (value for time) and an employee perspective (value for money). In other words, reservists consider themselves ‘paid volunteers’. Models for understanding volunteer and employee tensions describe the factors that influence reservists’ level of satisfaction and decision to resign. HR practices in the Army focus on the employee motivation of reservists. Thus, developing HR policies and practices that consider the volunteer motivations of reservists may increase retention.

Reserve service research

Given the level of Reserve contribution to operations worldwide, there is surprisingly little academic thought dedicated to Reserve research. While recent research into reservist motivations is limited, there are some opinion papers and academic research that relate specifically to Reserve issues. Alex Douglas’s ‘Reclaiming Volunteerism’ offers many important insights into Reserve service, but stops short of identifying Reserve salaries as the key difference between reservists and volunteers.7 Other research targets issues such as Reserve retention after deployment, family impact on reservists during mobilisation, and the degree to which military leadership will accept Reserve casualties.8

The first significant effort to specifically understand ADF Reserves through survey methods began in the late 1990s. Subsequent reports used statistical trends to understand Reserve attitudes to part-time ADF service. These reports reviewed motivation to join, key issues of importance to reservists and factors that could boost their retention.9 This significant body of quantitative research focused on quantifiable, measurable types of information. However this type of research is not equally balanced by qualitative research. Qualitative research records qualities that are descriptive, subjective or difficult to measure, allowing the voice of the individual to be heard.10 This study aims to fill the gap in Reserve-focused qualitative research. The use of a qualitative approach means that this research can seek to confirm or challenge statistical findings, while also describing the reasons reservists respond to HR impacts on their service. Researching the reasons for resignation through qualitative research provides information that statistics cannot, and therefore complement current Department of Defence data.

To better understand the experiences of Army reservists in joining, serving and leaving the Reserves, the research used a specific form of qualitative research called phenomenology. The main research questions are posed from the position of ‘how’ a phenomenon occurs, while supporting questions that address the ‘what’ is happening within the phenomenon. In effect, it examines how individuals perceive their service and what has shaped this.11

The research questions addressed in this study are:

- Is serving as a reservist unique, and if so, what is unique about it?

- How do reservists experience and view their Reserve work?

- What model (if any) can be developed to represent the Reserve service experience?

- How do reservists experience resignation and their decision to stay or leave?

- What kind of event, or events, cause a reservist to resign?12

Data analysis used a descriptive empirical phenomenological method. The descriptive element of this analysis seeks to describe what is unique and looks for themes to explain how it is unique. The empirical part of the analysis then compares the themes with existing research models and theories such as the quantitative research conducted by Defence and others mentioned earlier. Using this approach allows the research to reinforce the findings of previous quantitative research and also to find or develop new theories or models for understanding what is happening — in this case, the phenonomen of Reserve resignation and retention.

Unique but ambiguous employment proposition

Defining Reserve service has long been problematic and the unique nature or standard employment of reservists remains an ongoing question.13 The Defence Act 1903 (Cth) provides the legal framework for ADF Reserve employment, defining reservists as ‘personnel who do not ordinarily render full-time service’.14 Army reservists are bound by the Act and regulations to meet training period obligations.15 They are not bound to render continuous full-time service unless called out or electing to do so. Essentially, Reserve service is defined by what it is not — full-time employment. This may underpin the recent use of the term ‘part-time service’.

Reserve service does not constitute a form of part-time employment or a form of unpaid volunteerism under industrial relations definitions.16 Reservists are not part-timers because they do not work a full-time employee pro-rata week, but generally have set attendance patterns. Under the Department of Defence’s workforce reform plan, Plan Suakin provides part-time service that differs from routine Reserve service in that it is a pro-rata arrangement for members of the Regular Army to work part-time. Reservists are paid employees, not volunteers; however, manuals and instructions contain provisions for reservists to work without payment.17 While reservists are similar to casual employees given their shift-like employment pattern and remuneration, Reserve service and casual work also differ due to the tax-free status of Reserve pay.18

Casualised workforces enable employers to hire and retrench employees with little, if any notice. When the government institutes budget cuts, discretionary spending is one of the first areas affected. The survey participants in this study provided many examples of fluctuations in Reserve salary budgets. In 2009 and 2013, for example, budget cuts for the Reserve became newsworthy with ‘cut[s] from as many as 48 to 24 [training day salaries per soldier], which would severely reduce operational readiness and probably result in mass resignations from the ranks’.19 The governments of other countries have also instituted similar cuts in times of budget stringency.20

The culture of a casualised workforce may not support the depth of commitment expected of the Reserve workforce. At times, reservists are given limited notice regarding upcoming periods of employment. The Army’s preference for a Reserve force that is trained and available for short-notice employment in a range of roles is well documented.21 However, the notion of the Army reservist as a ‘casual’ employee rather than a part-time member has the potential to adversely affect the way that members of the full-time force view reservists – both in commitment to serve and quality of capability.

Increasing expectations of reservist availability do not align with the parameters of casual employment. One participant told the study: ‘[Reserve service will] take as much of your time as you’re prepared to give it, and then they’ll ask for more – always’. Another participant agreed with this sentiment, adding: ‘the commitment that is expected … [is] a big one’. Australian and UK-based participants assert that the demands on, and increasing expectations of reservists are not aligned to any other casual employment commitment. As a consequence, Reserve service is regarded as more than ‘casual employment’, but cannot be deemed ‘part-time employment’, and therefore more appropriately recognised as a unique form of employment.

Identifying Reserve service as unique employment sets the conditions for examining reservists’ descriptions of their experiences. This allows the identification of themes in the analysis of reservists’ motivation, satisfaction and decision to resign.

The Reserve experience and perceptions of work

This research highlights two notable insights into the service experiences of reservists. First, the survey data gathered for this research confirms the view of Lomsky-Feder et al. who describe reservists through the metaphor of their lives as ‘transmigrants’.22

The transmigrant metaphor presents an innovative viewpoint for exploring the specific social and organisational qualities of military Reserves. Reservists migrate swiftly and regularly between the military and civilian world. Lomsky-Feder et al. argue that reservists have ‘different patterns of motivation, cohesion, political commitment and awareness, and long-term considerations that characterize each [world]’.23 They describe the way reservists feel: they belong and yet do not fit into the military system; their civilian co-workers regard them as similar, but different due to their military service. Reservists have invested in both military and civilian life and are constantly moving as ‘migrants’ between military and civilian worlds. The experiences described by the participants in this research confirm the insights of Lomsky-Feder et al. Both UK and Australian participants openly discussed the unique sense of ‘belonging’ to the Reserve, but at times of not fitting into the broader Army. They described being both connected and disconnected from civilian colleagues because of their service and the tensions of managing other interests.

Secondly, this research also found that many reservists consider themselves both paid employees and unpaid volunteers. The ambiguity of Reserve service underpinned this line of investigation. The participants were provided the industrial relations definitions for the terms ‘paid employees’ and ‘unpaid volunteers’ and were then asked to define themselves as either an employee or a volunteer. Most struggled to describe their employment model. In analysing their responses, their literal response was considered alongside examination of what motivated them based on the motivations of employees versus the motivations of volunteers which, according to current research, can be significantly different. For example, volunteers are not motivated by remuneration as they are not paid. Seven of the nine participants presented information that indicated they considered themselves both employees and volunteers.24 Of the remaining, a university student clearly perceived his service as paid employment, whereas a long-serving warrant officer explained that he would be willing to serve without remuneration. Analysis of each interview revealed evidence of changing volunteer/employee motivations and differing levels of satisfaction for each individual. These responses highlight the fact that the participating reservists regard themselves as ‘a bit of both’ — a hybrid of employee and volunteer.25

Paid volunteer satisfaction and lifecycle

Reservists with a hybrid perception of service often face the tensions of competing employee/volunteer motivators and satisfiers. Employee and unpaid volunteer work motivation and satisfaction differ. While employees and volunteers may perform the same work, the actual or perceived rewards for that work vary. Volunteers’ motivation to work without remuneration differs from that of paid workers. Motivation/satisfaction theories — such as described by Maslow in his hierarchy of needs theory — suggest that volunteers’ lower order needs such as security, shelter and sustenance are met elsewhere26 (including other work, pension, working partner). While paid work fills the lower order needs such as shelter, food and security, volunteering invariably satisfies higher order needs such as self-actualisation.27 Maslow’s higher order needs are those intangible rewards felt by participants in activities beyond basic survival.

Given reservists’ lack of clarity in describing their employment model, thematic analysis was conducted which found that the Reserve experience correlates to both employee and volunteer satisfiers. Reservists are satisfied by their service through perceptions of being both an employee and unpaid volunteer (see Table 1).28

The study also revealed tensions between volunteer-like and employee motivation, with some themes revealing that participants were motivated in a similar way to volunteers. These motivators included the ‘anticipated benefits of the activity’,29 and the fact that the organisation ‘was doing admirable work and there were other non-monetary benefits [to] the volunteer’.30 Participants’ strong focus on ‘culture and identity’ highlighted the importance of the ‘social systems and support networks’ that Reserve service provides.31 Likewise, participants’ focus on a ‘sense of belonging’ to the Reserve strongly aligns with compensation theory knowledge. Compensation theory applies to those participants who explained that Reserve service compensates for the satisfaction they do not receive in their civilian work, such as taking part in exciting military activities or feeling ‘set apart’ from their civilian colleagues.32

Table 1. Reserve satisfiers compared with employee and volunteer satisfiers

| 1. Reserve satisfiers | 2. Herzberg (employee satisfiers) | 3. Volunteer satisfiers |

| Deploying | Work content | Help others or community Use skills or experience Do something worthwhile |

| Courses, learning, training, transferable skills | Work content | Use skills or experience Gain work experience Learn new skills |

| Camaraderie | Good relationships |

Stemming naturally from involvement in an organisation Social contact |

| Exercises | Work content | Use skills or experience Be active |

| Adventure training | The challenge | Be active |

| Responsibility | Responsibility | — |

| Live firing | Work content | Be active |

| Doing something different | — | Do something worthwhile |

| Parades | — | Stemming naturally from involvement in an organisation |

| Promotion | Praise and recognition | — |

| Travel | — | — |

| — | Achievements | — |

| — | Autonomy | — |

| — | Personal or family involvement | |

| — | — | Gain personal satisfaction |

| — | — | Relating voluntary work to religious beliefs |

There was also evidence that participants’ motivation closely resembled that of employees. Participants readily discussed issues concerning remuneration and benefits, training, hiring, administration and their relationship with Regular Army staff. Here the push/pull factors model is relevant, as it describes employee retention in terms of ‘pull factors’ (the attractions of civilian life) and ‘push factors’ (the disadvantages of service life).33 Participant focus on employee-like topics aligned to push factors such as ‘salary, company policy and administration, supervision, working conditions, and interpersonal relations’.34

The unique Reserve service proposition occurs, in part, as a result of the ambiguity of reservists’ sense of belonging to both the military and civilian spheres of their lives. Both UK and Australian reservists struggle to define the employment model in which they work. Their motivation to serve and satisfaction from service draws on both volunteer-like and employee examples. The motivation and satisfaction of employees conflicts with that of volunteers and explains, to a certain extent, the challenge of retaining reservists. The tensions between volunteer and employee motivations underpin the remaining research findings.

The above analysis points to the reservist psyche as a paradox rather than a dichotomy. Reserve service is not an ‘either/or’ frame of reference. The employee/ volunteer motivation ebbs and flows between the two mindsets and can coexist in each individual’s thinking.

A reservist’s stage of life shapes his/her perception of service. As reservists experience service, other events and contexts influence the extent to which they perceive themselves as volunteers or employees. For example, if reservist currently view themself more as volunteer, there are still aspects of service they can experience from an employee’s perspective because of their current stage of life. A warrant officer participant considered himself purely as a volunteer, but readily described the need for Reserve superannuation, as appropriate to his age and length of service.

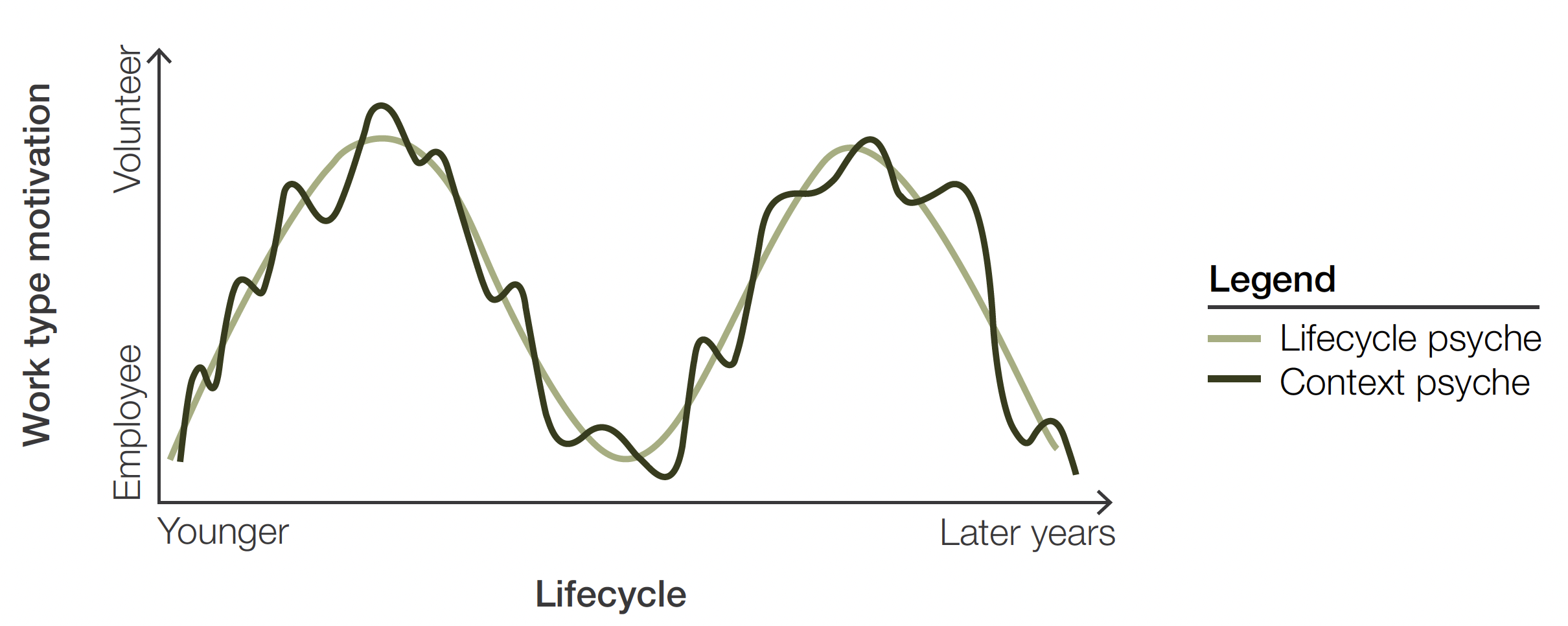

Figure 1 graphically depicts the ebbs and flows of the lifecycle mindset (dark line) and the fluctuations within this due to context or events (pale line) over time. Both relate to volunteer and employee motivation. Each individual will start and finish at different points on the graph. Some will start at a more volunteer-based position, others at an employee-based start point. This research found that reservists may start with a volunteer mindset and feel more like an employee in the later stages of their career. Others may join for the salary and later enjoy voluntary elements of service.

Figure 1. Reservists’ paid-volunteer lifecycle

As each participant experienced different events in his/her personal life or Reserve service, the motivation to serve altered or became more weighted towards an employee or volunteer mindset.35 Enjoyable Reserve activities that make such service different to civilian work (volunteer mindset), or fewer enjoyable tasks and heavy burdens such as administration (employee mindset), also changed participants’ views of Reserve service.

Reservists unconsciously layer these short-term experiences onto their overarching view of their service. By doing so, tensions appear between the motivations to serve as an employee and a quasi-volunteer. The ever-changing view of ‘self’ as described by the participants, also affects their expectation of the ADF and its policies and practices. Indeed, they may view the same policy from different perspectives depending on their mindset at the time.

This theory highlights the opportunities to better understand Reserve motivation and satisfaction as a unique psychological or motivational model. If these participants are representative of other reservists, as suggested by transmigrant theory, then it will be important to develop suitable Reserve-specific HR policies and practices to maintain Reserve motivation.36 If Defence adopts an employee-only focus in setting policy, a natural conflict between employee policy and volunteer-like motivation may arise, causing those who are motivated as volunteers to feel unfulfilled. The converse is also possible. Volunteer-like policies may also alienate those who regard themselves as employees.

The resignation experience

Many participants asserted that the Army has high expectations of the modern reservist. These expectations can, at times, lead to resignation. The participants provided examples that included separation from partners due to Reserve service, the intrusion of Reserve service into civilian careers and the impact of Reserve service on other aspects of life. While these issues did not automatically cause the resignation of participants, a common thread from ex-serving participants’ experiences was the issue of ‘time’. Their perception was that their time was valuable and could be better spent doing other activities.

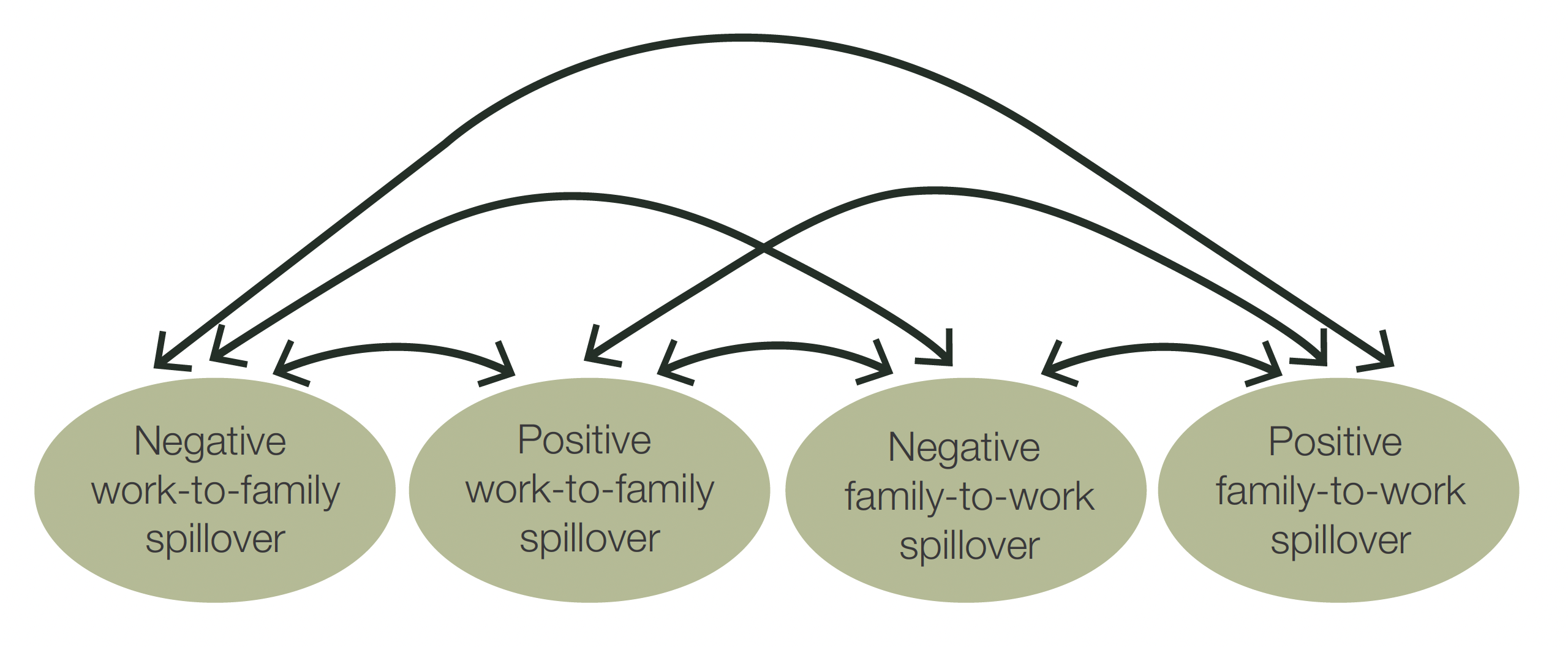

An existing theory of motivation, satisfaction and resignation known as ‘spillover theory’ is relevant here. The process of ‘spillover’ occurs when ‘an employee’s experience in one domain [of his/her life] affects their experience in another domain’.37 Considered the most accurate view of the relationship between work and family, spillover describes multi-dimensional aspects of the work-family relationship. The four-factor spillover model (Figure 2) proposes positive and negative interrelationships between home and work.38

Figure 2. Kinnunen, Feldt, Guertes and Fulkkinen’s four-factor spillover model

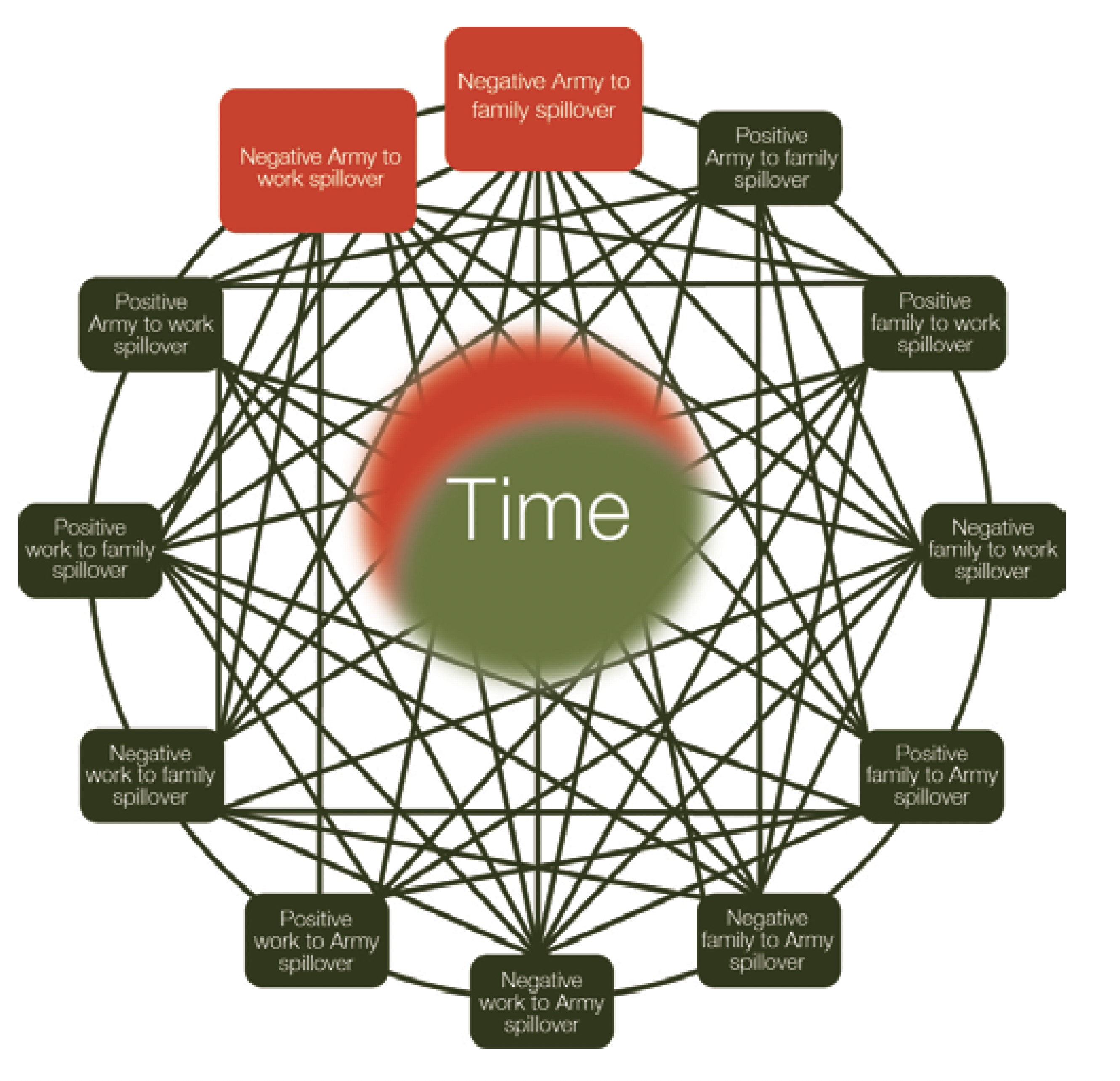

Spillover theory becomes significantly more complex when Reserve service is added to the model. By adding Reserve service, the model changes from a four- factor model to a 12-factor model.39 The 12-factor model was developed prior to data collection because the literature suggested that life with Reserve service was signficantly more complex. The Figure 3 model shows this to be the case. Following data analysis, the research revealed that ‘time’ was central to the positive and negative influences of the Army on non-service life. The model was further adjusted to include time to be central to the model.

The research demonstrated that participant perceptions of the Army’s negative spillover effects magnify over time (see Figure 3).40 Time is shown in the centre of all the spillover effects. The negatives of service increase in size and become more negative in the eyes of the affected reservist (red). As the negative spillover increases, it is perceived to erode time.

Figure 3. Reservists’ spillover theory model

Previous surveys and interviews with serving members did not conclusively demonstrate the strength of pull factors for members who leave. With the inclusion of ex-serving members, this research identified that reservists commonly leave because of the tensions of finite time and the inability to manage time within their transmigratory lives.41 This significant insight into the tensions of Reserve life is important in identifying likely resignation trends.

Resignation event or events

In contrast to existing Defence survey data that infers a critical event as the precipitant, this research found that reservists often do not leave because of a single event.42 Additionally, this research identified that serving reservist perceptions of reasons to leave are not likely to be predictors of future resignation.

Multiple incidents, underpinned by spillover time pressures, push and pull factors43 and an emphasis on aspects of work, cause dissatisfaction as described by Herzberg.44 Serving participants perceived push factors as providing more plausible reasons to resign.45 Aspects of workplace conditions within the service that may prompt resignation include being ‘stuffed around’, being forced to leave, or being ‘picked on’.46 Only one serving participant mentioned a pull factor — that being that his military career has a negative impact on other aspects of life. A 2004 ADF Reserve report cites increasing Reserve pay, providing a retention bonus/financial reward, improving allowances and providing Defence-sponsored superannuation as possible incentives for persuading reservists to continue to serve.47 All the elements of the survey relate to service life and thus focused only on push factors. There is arguably a gap in that the ADF report did not fully consider the possible pull factors to retention or resignation and subsequent efforts to counter the pull to leave.

This research and previous surveys reinforce the proposition of ‘value for money’ for reservists motivated by employee-like satisfiers. Current theory points to these factors as causing people to become dissatisfied (push factors), while other research suggests that these are not factors that would satisfy or retain members.48 The surveys and interviews of serving members did not convincingly demonstrate the strength of pull factors for members who leave, given that these participants had no experience of resignation.49

By contrast with serving participant views, ex-serving participants explained that the decision to leave was not a rapid, impulsive decision, but often seriously considered over a significant timeframe. As noted in spillover theory, the ex-serving participants clearly assessed ‘time’ as a tangible pull factor to leave, particularly the inability to manage time within their transmigratory lives. While there are suggestions that civilian work hours appear to be increasing,50 the average hours worked by full-time employees have remained stable since the 1970s.51 The increase in work time appears to be more a result of the career progression of an individual rather than changes to statistical norms. Longer serving participants described experiences in which promotion to management level increased work hours. Reserve and civilian employment promotions often parallel one another, with both demanding increased time commitment beyond standard work hours. This results in unpaid Reserve work becoming more visible to civilian employers and partners. For example, two participants described Reserve service as a key contributor to collapsed relationships.52

Ex-serving reservists assert that pull factors are a more likely determinant of resignation than push factors.53 Although time underpinned their resignations, the ex-serving participants described other cumulative experiences that also contributed to their decision to leave. One such experience was the erosion of the enjoyable aspects of service. Corporate governance tasks are identified as taking an increasing proportion of the time available for Reserve service. The repeated adage of ‘part-time army; full-time admin’ throughout the interviews emphasised this frustration. When Reserve service feels too similar to civilian work, the reservist may decide that precious ‘free time’ may be better spent on other activities. The pull of civilian life wins this battle.

Ex-serving reservists describe their resignation more in volunteer terms than those of employees. Phrasing such as the feeling of being unable to ‘dedicate my time to it’ is reminiscent of volunteer language, as an employee is less likely to offer that phrase when resigning from paid employment. While the value proposition for an employee is ‘value for money’, the proposition for the volunteer-like reservist is ‘value for time’.

The Department of Defence’s unconscious breaking of its psychological contract with employee/volunteer soldiers also contributes to resignation. The construct of a mutual agreement is the foundation of a psychological contract. According to psychological contract theory, employers and employees behave in a manner based on the supposed fulfilment of explicit or implicit promises made between the organisation and the employee.54 Further, employees’ psychological contracts with the organisation vary from person to person and, as such, they have different degrees and types of expectations of their employer. In short, a psychological contract is personal and subjective. However, shared psychological contracts or normative contracts are those in which people from situations that are similar — be it team, organisation or context — tend to build similar psychological contracts to other like-minded individuals. These may result from their similar values, job descriptions, employment conditions or other similarities. Nevertheless, individuals will still interpret the employer promise (job security, salary, commission, and holidays) in unique ways based on historical norms of what they have previously received in return for work or service.55

Increasing demands on reservists’ time and commitment create a psychological contract that reinforces their valuable contribution to ADF capability. The ex-serving participants in particular described the consequence of dramatic changes to Reserve commitment as quasi-casual employees in response to budget reductions. They perceived Defence’s appreciation of the value of Reserve service as fickle, believing that their ‘volunteer’ time was no longer valuable to Defence, undermining higher order needs such as self-actualisation. The ever-changing pressures on Reserve commitment therefore contribute to Reserve resignation. Participants believed that Defence messaging on the value of the Reserves is consistent, but that there is inconsistent action to support this over budget cycles.

Conclusion

This paper addresses the unique nature of Reserve service and the reasons for resignation identified in recent doctoral research. This research suggests that reservists are motivated by both employee and volunteer motivations, a result of ambiguity within the Reserve service proposition. Reserve service is largely described in the Defence Act 1903 (Cth) by what it is not and does not neatly fit into an industrial relations or HR definition of employment. As a result, reservists find it difficult to accurately describe their service.

Reservist resignation occurs when the volunteer and employee satisfiers compete and is often the result of multiple pull factors to civilian life, with time at the core. The models presented illustrate how reservists also resign when the spillover tensions from Reserve service become untenable. The opposing psychological differences between being a paid employee and a volunteer represent a significant contributing factor to the high rate of resignation.

Developing HR policies and practices that accommodate the ‘paid volunteer’ motivations of reservists may improve future retention and personnel capability. The unconscious ambiguity of employment status may negatively influence policymaking with repercussions for the experiences of the reservist. The nature of Reserve service is unique and requires further research. This paper recommends that Defence seek a better understanding of the nature of this service and develop more effective HR policy and practices in the future that can accommodate the various intrinsic and extrinsic factors that may prompt reservists to leave. The complexity of Reserve service means it cannot be resolved through a quick, single- focus policy, program or practice. It must be more than a modified version of full- time conditions, but rather a carefully considered suite of policies uniquely reflecting the nature of Reserve service.

Reserve HR policy must balance the employee and volunteer motivators and satisfiers to sustain future forces. While emerging Reserve HR policy is unlikely to affect future recruitment success, it is highly likely to have beneficial effects on retention. Current policy sufficiently addresses the ‘value for money’ proposition for employment, ensuring the ‘push’ disadvantages of service life are managed. The quality of policy implementation into practice varies and has mixed results on push of reserve resignation. Regardless, more focus on countering the ‘pull’ attractions of civilian life is required so that the paid volunteer perceives service as ‘value for time’.

Endnotes

1 A. Podger, D. Knox and L. Roberts, Report of the Review into Military Superannuation Arrangements, Canberra: Department of Defence, 2007, p. 43.

2 Ibid.

3 Department of Defence, Defence Annual Report, Canberra: Department of Defence, 2001–02, 2007-08, 2009–10, 2011–12. Department of Defence, Army Reserve Pocket Book as at Jun 15, Canberra.

4 The United Kingdom Territorial Army is now referred to as the Army Reserve.

5 The current Reserve recruiting campaign slogan is ‘Do Something for Yourself and Your Country’. See http://www.defencejobs.gov.au/army/reserve/.

6 Department of Defence, Defence White Paper 2009: Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030, Canberra: Department of Defence, 2009; Australian Government, Australia in the Asian Century, Canberra, 2012; J. Reich, J. Hearps, A. Cohn, J. Temple and

P. McDonald, Defence Personnel Environment Scan 2025, Canberra: Directorate of Strategic Personnel Planning and Research, 2006; T. Schindlmayr, Defence Personnel Environment Scan 2020, Canberra: Directorate of Strategic Personnel Planning and Research, 2001.

7 A. Douglas, ‘Reclaiming Volunteerism: How a Reconception Can Build a More Professional Army Reserve’, Australian Army Journal, 9: 1, Autumn 2012, p. 13–24, http://www.army.gov. au/Our-future/Publications/Australian-Army-Journal/Past-editions/~/media/Files/Our%20future/ LWSC%20Publications/AAJ/2012Autumn/03-ReclaimingVolunteerismH.pdf.

8 L. Gorman and G.W. Thomas, ‘Enlistment Motivations of Army Reservists: Money, Self- improvement, or Patriotism?’, Armed Forces and Society, 17: 4, 1991, pp. 589–99; S.N. Kirby and S. Naftel, ‘The Impact of Deployment on the Retention of Military Reservists’, Armed Forces and Society, 26: 2, 2000, pp. 259–84; L.N. Rosen, L.Z. Moghadam and N.A. Vaitkus, ‘The Military Family’s Influence on Soldiers’ Personal Morale: A Path Analytic Model’, Military Psychology, 1: 4, 1986, pp. 201–13.

9 See J. Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists, EdD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 2014, for full bibliography of Defence reports consulted.

10 Quantitative research, particularly if methods focus on questionnaires, allow researchers to gather data across large organisation like the Department of Defence; generalising statistical data across diverse participants also has the tendency to pigeonhole people. Phenomenology, as a qualitative research method, provides a balance that allows the voice of the individual to be heard.

11 In phenomenological research, the research topic is formed from an intense interest in a particular problem or topic. A researcher’s enthusiasm and inquisitiveness should positively underpin the research and ‘personal history brings the core of the problem into focus’. See

C. Moustakas, Phenomenological Research methods, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1994, p. 104. Phenomenologists want to know what participants are experiencing and how they experience it. See L. Finlay, Introducing Phenomenological Research, http:// lindafinlay.co.uk/phenomenology/. This is true in the case of the author whose own Army Reserve experience motivated the research — a true insider’s research. See T. Brannick

and D. Coghlan, ‘In Defense of Being “Native” — The Case for Insider Academic Research’,

Organizational Research Methods, 10: 1, 2007, pp. 59–74.

12 This paper cannot present all the questions and findings from the research and therefore selectively presents the most illustrative results. For the full research thesis, see Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists.

13 Podger et al., Report of the Review into Military Superannuation Arrangements.

14 Australian Government, Defence Act 1903, Canberra, http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Series/ C2004A07381.

15 The Act accommodates the various types of Reserve service such that the regulations can specify differing training obligations between Active and Standby Reserves.

16 Department of Defence, Pay and Conditions Manual, Canberra, http://www.defence.gov.au/ dpe/pac.

17 Unpaid voluntary work or attendance is recorded in accordance with Defence Instruction (Army) DI(A) PERS 116–12—Voluntary Unpaid Attendance by Members of the Army Reserve.

18 A full-time employee has ongoing employment and works, on average, around 38 hours per week (see Australian Government, Fair Work Ombudsman, Canberra, www.fairwork.gov.au).

A part-time employee is a person usually working fewer than 38 hours a week and paid by one employer. However, a part-time or full-time worker may engage in other part-time work with subsequent employers (see Fair Work Ombudsman). Contractors are engaged and paid by an employer to complete a particular piece of work for a fixed period of time (see Office of Human Resources — Murdoch University, Determining the Employment Status of the Consultant / Independent Contractor, Western Australia: Murdoch University, 2006). A casual employee

has no guaranteed hours of work, usually works irregular hours, does not receive paid sick or annual leave and can terminate employment without notice, unless notice is required by a registered agreement, award or employment contract (see Fair Work Ombudsman). Casuals are generally hired to fill labour gaps although there is no set definition of what constitutes a casual employee (see R. Jackson, ‘When is a Casual Employee not a Casual Employee?’,

Human Resources, Sydney: Key Media, 2003). Similar to contractors, casuals often forego leave entitlements and receive hourly-rate payments that may include a leave loading; however, casuals and employers have an ongoing work agreement unlike contractors who have

fixed-term employment. Finally, a volunteer is a person who partakes in ‘an activity which takes place through not for profit organisations and is undertaken to be of benefit to the community and the volunteer’, without financial payment (Volunteering Australia, ‘Definitions and principles of volunteering’, Canberra, January 2006, www.volunteeringaustralia.org/sheets/definition.html).

19 ‘Army Reserves Won’t get Anzac Day Pay’, The Australian online, April 2010, www.theaustralian.com.au/news/army-reserves-wont-get-anzac-day-pay/story- e6frg8yo-1225851134715.

20 B. Johnson, S. Kniep and S. Conroy, ‘The Symbiotic Relationship Between the Air Force’s Active and Reserve Components’, Air and Space Power Journal, Jan–Feb 2013, pp. 107–29; ‘Guard and Reserve Units Fight for Funds amid Budget Cuts’, Army Times, September 2014, www.armytimes.com/article/20130906/NEWS02/309060011/Guard-reserve-units…- amid-budget-cuts.

21 M. Vertzonis, ‘Reserve Hardens Up’, Army – The Soldier’s Newspaper, 24 August 2006, p. 2, http://www.defence.gov.au/news/armynews/editions/1150/personnel.htm.

22 E. Lomsky-Feder, N. Gazit and E. Ben-Ari, ‘Reserve Soldiers as Transmigrants: Moving Between the Civilian and Military Worlds’, Armed Forces and Society, 34: 4, 2008, pp.593–614.

22 Ibid., p. 609.

24 Seven participants presented data that referred to both employee and volunteer approaches to service. See Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists, pp. 116–19.

25 Ibid.

26 C.P. Alderfer, Existence, Relatedness, and Growth; Human Needs in Organizational Settings, New York: Free Press, 1972; A. Bandura, ‘Self-efficacy’, Harvard Mental Health Letter, 13: 9, 1997; F. Herzberg, ‘One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?’, Harvard Business Review, September–November 1987; A.H. Maslow, ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’, Psychological Review, 50: 4, 1943, pp. 370–96; J. Simons, B. Irwin and B. Drinnien, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Psychology — The Search for Understanding, New York: Publishing Company, 1987.

27 Maslow, ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’; Simons et al., Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

28 Table 1 presents comparative analysis conducted on participant satisfaction of service themes (column 1) against employee (column 2) and volunteer satisfiers (column 3). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Volunteerism’, Canberra, 2005. See also Herzberg, ‘One more time: How Do You Motivate Employees?’

29 J.E. Mutchler, J.A. Burr and F.G. Caro, ‘From Paid Worker to Volunteer: Leaving the Paid Workforce and Volunteering Later in Life’, Social Forces, 81: 4, 2003, pp. 1267–93, p. 1269.

30 M.A. Okun, A. Barr and A.R. Herzog, ‘Motivation to Volunteer by Older Adults: A Test of Competing Measurement Models’, Psychology and Aging, 13, 1998, pp. 608–21.

31 C. Toppe, A. Kirsch and J. Michel, Giving and Volunteering in the United States, Waldorf MD: Independent Sector, 2001.

32 S.J. Lambert, ‘Processes Linking Work and Family: A Critical Review and Research Agenda’, Human Relations, 43, 1990, pp. 239–57; C.S. Piotrkowski, Work and the Family System: A Naturalistic Study of Working-class and Lower Middle-class Families, New York: Free Press, 1979.

33 L.T. Jones, D.J. Murray and P.A. McGavin, ‘Improving the Development and Use of Human Resources in the Australian Defence Force: Key Concepts for Strategic Management’, Australian Defence Force Journal, 142, Jun/Jul 2000, pp. 11–20.

34 K. Farrell, ‘Human Resource Issues as Barriers to Staff Retention and Development in the Tourism Industry’, Irish Journal of Management, 22:2, 2001, pp. 121–25.

35 Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists, p. 189.

36 Lomsky-Feder et al., ‘Reserve Soldiers as Transmigrants’.

37 P.M. Hart, ‘Predicting Rmployee Life Satisfaction: A Coherent Model of Personality, Work and Non Work Experience, and Domain Satisfaction’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 1999,

pp. 564–84.

38 G. Garza, ‘Varieties of Phenomenological Research at the University of Dallas’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 4: 4, 2007, pp. 313–42; Kinnunen, Feldt, Geurts and Fulkkinen four- factor spillover model as cited in K.M. Lavassani and B. Movahedi, Theoretical Progression

of Work and Life Relationship: A Historical Perspective, Ottowa: Sprott School of Business, Carleton University, 2007.

39 Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists, p. 80.

40 Ibid., p. 230.

41 Lomsky-Feder et al., ‘Reserve Soldiers as Transmigrants’.

42 This refers to the analysis of the numerous Defence survey reports.

43 Jackofsky cited in K. McBey and L. Karakowsky, ‘Examining Sources of Influence on Employee Turnover in the Part-time Work Context’, Career Development International, 6: 1, 2001,

pp. 39–48; Jones et al., ‘Improving the Development and Use of Human Resources in the Australian Defence Force’.

44 Herzberg, ‘One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?’.

45 Jones et al., ‘Improving the Development and Use of Human Resources in the Australian Defence Force’, p. 15.

46 Ibid.

47 Defence Personnel Executive, Australian Defence Force Reserve — Attitude Survey Report, Canberra: Department of Defence, 2004.

48 Alderfer, Existence, relatedness, and growth; Bandura, ‘Self-efficacy’; D. Droar, Expectancy Theory of Motivation, Bracknell, UK: Arrod and Co, [2007]; Herzberg, ‘One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?’, Maslow, ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’; Simons et al., Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

49 Jones et al., ‘Improving the Development and Use of Human Resources in the Australian Defence Force’, p. 15.

50 G. Pankhurst, ‘Why Are Australian Workers Doing More Hours?’, Linkme Jobs website, www. linkme.com.au/members/resources/articles/career-management-in-the-work-place-why-

are-australian-workers-doing-more-hours/e89f2f11-13e3-451e-bd5b-a59230f36fc3; L. Carter, ‘Australian Workers More Stressed Than Ever Before’, ABC radio, www.abc.net.au/ worldtoday/content/2013/s3858968.htm; B. Pike, ‘Work/life balance - how to get a better deal’, www.news.com.au/finance/work/worklife-balance-how-to-get-a-better-deal/…- e6frfm9r-1226282044906.

51 R. Edwards (ed.), Yearbook Australia 2009-2010, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 2010.

52 Lording, Paid Volunteers – Investigating Retention of Army Reservists, p. 142.

53 Jones et al., ‘Improving the Development and Use of Human Resources in the Australian Defence Force’, pp. 11–20.

54 J. Hallier and P. James, ‘Middle Managers and the Employee Psychological Contract: Agency, Protection and Advancement’, Journal of Management Studies, 34, 1997, pp. 703–28.

55 C.P. Chang and P.C. Hsu, ‘The Psychological Contract of the Temporary Employee in the Public Sector in Taiwan’, Social Behavior and Society, 37: 6, 2009, pp. 721–28; V. Ho, ‘Social Influence on Evaluations of Psychological Contract Fulfillment’, Academy of Management Review, 30: 1, January 2005, pp. 113–28; M. Kim, G.T.Trail, J. Lim and Y.K. Kim, ‘The Role of Psychological Contract in Intention to Continue Volunteering’, Journal of Sport Management, 23, 2009, pp. 549–73; D.M. Rousseau, ‘Schema, Promise and Mutuality: The Building Blocks of the Psychological Contract’, Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 74: 4, November 2001, p. 511.