Abstract

Success in counterinsurgency requires a careful balance between the ability to win the support of the people, and a finely honed close combat ability which can crush the enemy with precision whenever and wherever the opportunity arises. This article examines these issues from a commander’s perspective with a focus on counterinsurgency operations in Uruzgan in the second half of 2009. In doing so it focuses on two primary areas in which MRTF-2 modified its operational techniques: dispersed operations and influence. This article is an extract from a more comprehensive Land Warfare Studies Centre Study Paper (No. 321). For the full context of the operations conducted, the additional techniques designed to support mental health and resilience, and a brief proposal for enhancements to mission specific training and whole of government coordination, please refer to the Study Paper.

... intelligence has to come from the population, but the population will not talk unless it feels safe, and it does not feel safe until the insurgent’s power has been broken.

– David Galula 19641

The Second Mentoring and Reconstruction Task Force (MRTF-2) deployed to Uruzgan, South Afghanistan, in May 2009 with the short-term aim of providing security for the Afghan National Elections, and the strategic goal of developing the capacity of the 4th Brigade of the Afghan National Army (ANA) to conduct counterinsurgency operations. The battle group formed at 1 RAR in Townsville during March 2009 with soldiers from across the 3rd Brigade, supported by specialists from across the Australian Defence Force. MRTF-2 entered Afghanistan in the middle of a very active ‘fighting season’ in the face of an evolving threat from the Taliban and had a strong impact on the progress of the counterinsurgency within the Uruzgan province. The approach was to dominate the threat while maximising influence on the people and the environment, with the objective of supporting and preparing the Afghan National Army to conduct the counterinsurgency independently. The success of MRTF-2 came as a result of the strength of character, resolve and initiative of all ranks.

Background

Environment

A large portion of Uruzgan is dasht (desert) or steep mountains of rock. These areas contain little life except for the nomadic Kuchi tribespeople. A small portion of the terrain consists of valleys in which all the available water, crops and life exist—these are referred to as ‘green zones’. The green zones are where the people live, and generally where the Taliban operate.

Green zones are extremely complex environments in which all land is privately owned and all structures are man-made. There are clay walls (which can be several feet thick) around most fields and around all dwellings. The Afghans live in compounded, high-walled residential complexes called q’alas. The flow of water to fields is controlled by a maze of deep and well crafted irrigation canals, many of which have walls on their banks, often supplied by large subterranean waterways known as karez. The tracks through the villages are designed to be negotiated on foot or on an animal (but not vehicle), with walls on either side of them, and generally cross the canals over very narrow and precarious foot bridges. Most communities grow three crops a year: typically poppy, wheat and corn. Each of these crops becomes high and dense as it matures, but the corn in particular can reach eight feet, creating a very dense close-country environment towards the end of summer. There are also dense orchards of almonds and apricots. The width of these valleys can range from merely half a kilometre to as much as ten kilometres. Maximum temperatures in summer can be above 45 degrees Celsius, while in winter minimums can be well below freezing. This is a challenging environment requiring largely dismounted operations.

Green zones are extremely complex environments in which all land is privately owned and all structures are man-made.

Structure

The original structure for MRTF-2 was directed to reflect exactly that of MRTF-1, with a single operational mentoring and liaison team (or ‘OMLT’, which was named ‘OMLT-C’, based on C Company 1 RAR) to mentor the ANA’s 2nd Kandak,2 a single combat team (Combat Team Alpha, or CT-A, based on A Company 1 RAR), a combat engineer squadron (based on 16 Combat Engineer Squadron from 3rd Combat Engineer Regiment), a combat service support company, and a battle group headquarters. Immediately prior to deployment, government decided to increase the force structure of MRTF-2 for two reasons: firstly, to provide additional combat power for operations in support of the national election security tasks (to be known as CT-B); and secondly, to enable an increased mentor effect (to be known as OMLT-D). This represented an increase in personnel and capability of almost 50 per cent on top of the original MRTF structure.

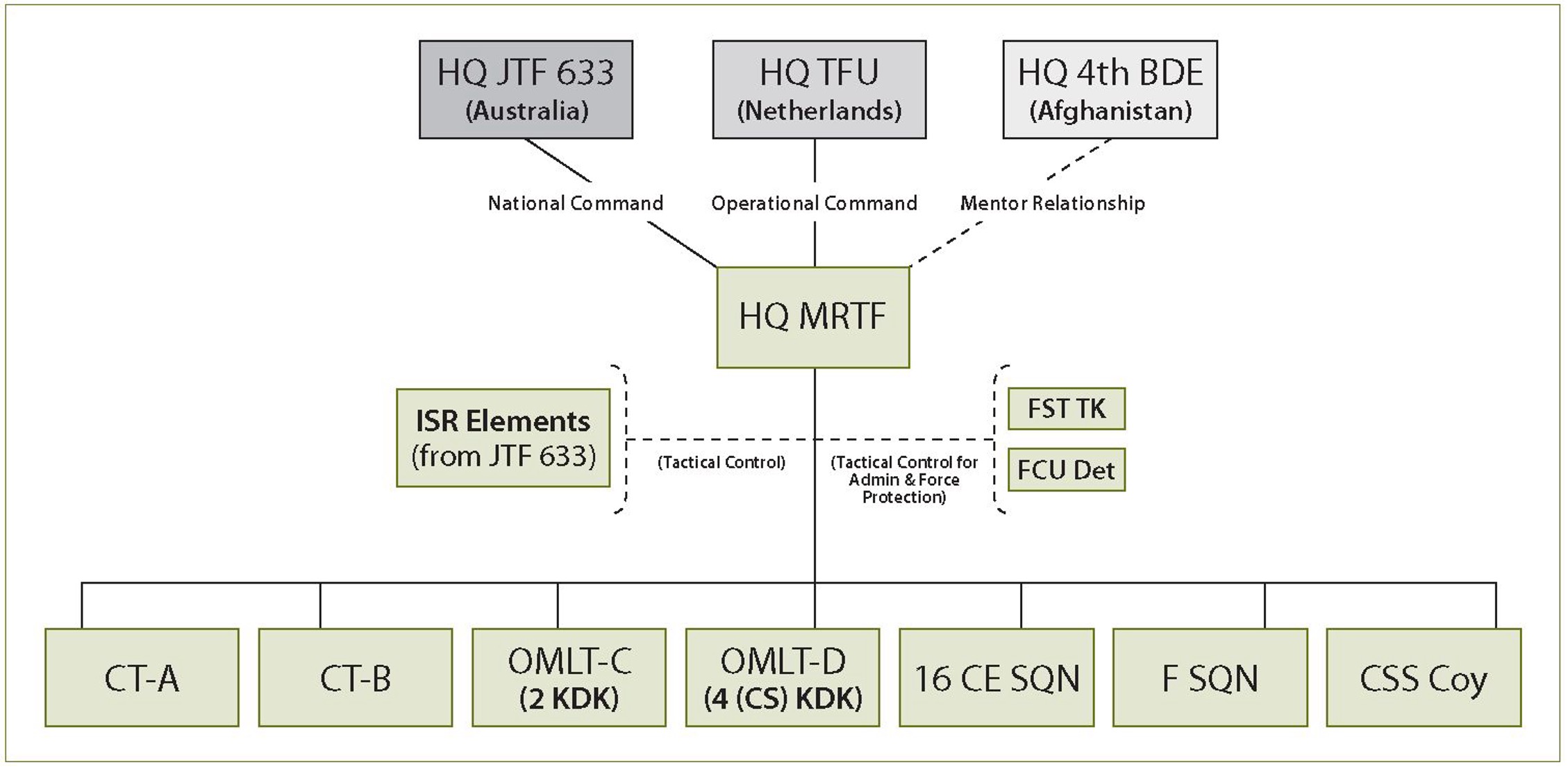

By September, total strength sat at around 730, with a battle group headquarters, battle group enablers (including joint fires teams from 4th Field Regiment, mortars and snipers from 1 RAR), a diverse intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) group, and seven sub-units3 (two OMLTs, two combat teams, a combat engineer squadron, a protected mobility squadron and a combat service support company).4 See Figure 1. MRTF-2 handed over to Mentoring Task Force One (MTF-1, based on 6 RAR) in February 2010.5

Operational Philosophy

MRTF-2 pursued four concurrent and interdependent lines of operation as part of a counterinsurgency-oriented mission:

- to mentor and build the capability of the 4th Afghan National Army (ANA) Brigade;

- to secure the people;

- to influence the population, the insurgency and the coalition; and

- to develop infrastructure and capacity within Afghan communities.

These lines described the different aspects of our mission that required resourcing, and provided a useful structure for weighing and adjusting the main effort against supporting efforts. The prioritisation and coordination of resources to achieve the commander’s intent was achieved through a targeting process.

Figure 1. MRTF-2 Structure

The mentor line of operations was the main effort of the battle group. All other lines of operation complemented this output, working towards 4th ANA Brigade being capable of conducting independent counterinsurgency operations. The philosophy adopted by MRTF-2 drew heavily from the foundations established by MRTF-1 with the 2nd (Infantry) Kandak. Our two OMLTs, each consisting of approximately seventy mentors between the ranks of private and major, had the lead on this line. We offered respect for Afghan experience and culture, and reinforced ANA ownership of the operation and the terrain, while at the same time demanding tactical outcomes and professional development. We encouraged the development of patrol plans for normal framework operations from the bottom of the chain of command (company level), and involved the ANA Brigade and Kandak commanders heavily in the planning and execution of all deliberate operations. OMLT-C took over mentoring of the 2nd Kandak from MRTF-1 in seven different patrol base locations. On the arrival of OMLT-D, we commenced the mentoring of the 4th (Combat Support) Kandak, and became closely engaged with Headquarters 4th Brigade to pave the way for this mentoring role to be formalised. This involved CO MRTF developing a close personal relationship with Commander 4th Brigade, which assisted in building stronger links between the respective chains of command.

We offered respect for Afghan experience and culture, and reinforced ANA ownership of the operation and the terrain ...

The mission of building the capacity of the 4th Brigade has required Australian OMLTs and combat teams to conduct partnered combat operations with ANA Kandaks since MRTF-1 commenced the mission in October 2008. Due to the aggressiveness of the insurgency and the dispersal of the ANA, we conducted patrols and operations side by side in high-threat areas, seeking to raise Afghan skill levels and achieve an operational effect simultaneously. As part of these activities we learnt a considerable amount about the environment and the people from the ANA. This mentoring effect was achieved by small groups of Australian soldiers operating independently in partnership with Afghan patrols of squad to platoon size from small patrol bases.

The secure line of operations was a supporting effort to MRTF mentoring objectives. We consistently reinforced and partnered with elements of the 4th ANA Brigade to ensure certain tactical preconditions were met on the ground and in doing so reinforce Afghan National Security Force (ANSF) credibility and Afghanistan government legitimacy. Though this line was normally a supporting effort, it underpinned the strong partnering relationship between MRTF-2 and 4th Brigade, and became the main effort for key objectives, such as election security. ANA and MRTF elements regularly reinforced each other throughout the tour in groupings from section to combat team size. The generation of confidence and credibility through tactical success is key to establishing a capable new force in a combat environment, and by successfully partnering with the 4th Brigade MRTF reinforced these objectives.

The influence line of operations aimed to develop and maintain a positive perception in the minds of all relevant audiences6 in relation to the capabilities of the Afghanistan government, the ANSF and ISAF. By developing the trust of the population in the government and the counterinsurgency force, we sought to separate the insurgents from their support bases. This line of operations emphasised the great importance of actions by soldiers at the local level to influence and convince the people. It also placed importance on cultivating and maintaining strong and positive links with all coalition partners. This required a well-synchronised information operations capability. The intent was for information operations to drive the way we operated by manipulating the influence line across all other lines of operations. We adopted the philosophy that all of our actions (including manoeuvre, construction and key leader engagement) would influence perceptions.

The develop line of operations sought the provision of infrastructure, construction related skills and the empowerment of local communities with the aim of enhancing local national support for the Afghanistan government and the ANSF. This is a continuation of the solid framework established by Reconstruction Task Forces One to Four, and was achieved through the integration of MRTF efforts with the Netherlands Provincial Reconstruction Team, AusAID, Afghanistan government agencies and local leadership. This line produced extremely complementary effects to those required by the influence, mentor and secure lines, and was significant to the achievement of Afghanistan government objectives as part of a holistic approach to counterinsurgency.

The develop line of operations sought the provision of infrastructure, construction related skills and the empowerment of local communities ...

This article refers particularly to two major deliberate operations: the provision of security for the Afghan national elections in Operation CRAM GHAR, and the clearance of the Mirabad Valley in Operation BAZ PANJE. However, it is important to note that there were three other deliberate operations, and more importantly that the soldiers of MRTF and 4th ANA Brigade conducted ‘framework operations’ on a daily basis throughout the area of operations. These framework patrols involved mentors operating with small teams of Afghans at platoon and squad level, combat team elements working at section and platoon group level, and later on armoured elements operating at patrol level. Often these elements combined at the lowest level, invariably with the support of combat engineers, joint fires teams and medics. It is only through the daily acts of professionalism, dedication, risk and resolve of these soldiers that the battle group was able to achieve the lines of operation described above. Focus is given to these two particular deliberate operations below because they best illustrate our techniques and their modification. There was considerable employment of framework operations within these deliberate operations.

Adapting With The Threat

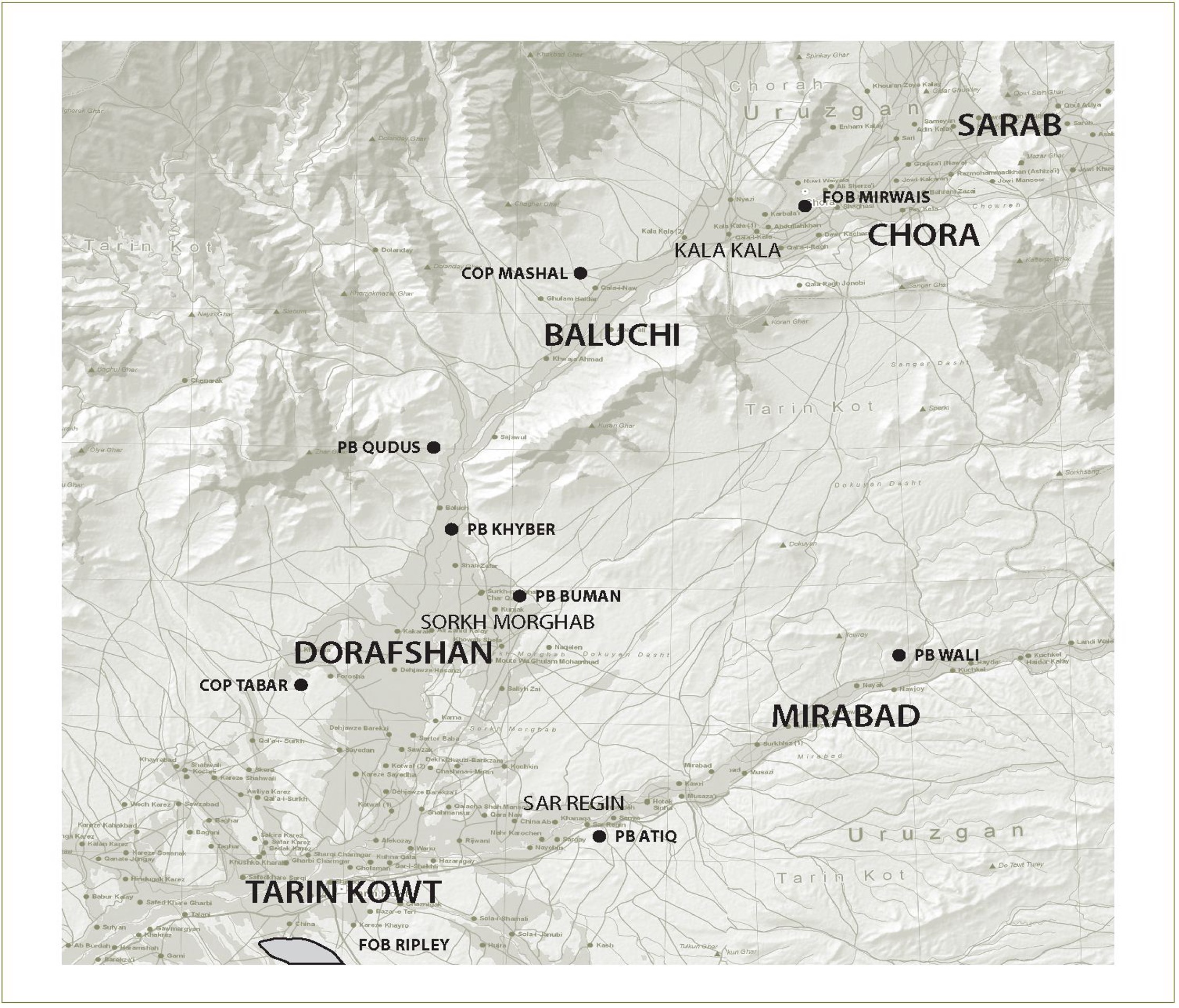

MRTF-1 had experienced a new threat in the Baluchi Valley (see Figure 2) in the months preceding the arrival of MRTF-2: there had been a number of wounded in action due to low metal content pressure plate improvised explosive devices (PPIEDs) targeting vehicles and some rapidly emplaced remote control IEDs (RCIEDs) targeting dismounted mentoring patrols. The incidence of these attacks increased dramatically during MRTF-2’s first month on the ground. This was the height of the ‘fighting season’ and the period immediately preceding the Afghan national presidential elections. It was also a time where MRTF expanded its ‘sphere of influence’ through increasing the radius of mentored dismounted patrols and eventually increasing the amount of combat power and the partnered footprint with the ANA on the ground.

The first serious casualties were from the crew of an engineer ‘Bushmaster’ Protected Mobility Vehicle (PMV)7 that was destroyed while following its search team on 7 July, the first day of Operation TUFANI BABAR (MRTF-2’s first deliberate operation). The section had been unable to detect the IED with the equipment available at the time. Less than two weeks later Private Ben Ranaudo was killed and Private Paul Warren was seriously wounded by a low metal content anti-personnel mine, which triggered a sizeable IED while they were participating in a dismounted combat team cordon and search on the western edge of Kala Kala. During the following month four more PMVs were lost to low metal content PPIEDs. It is extremely lucky there was no further loss of life and relatively minor wounds from a long stream of poorly employed or constructed RCIEDs used against dismounted patrols, several of which were part of complex attacks (supported by machine guns and rocket propelled grenades from different directions).

Figure 2. MRTF-2 and 2nd Kandak Area of Operations

Such experiences early in the tour gave cause to review and to question existing techniques. It was critical at this early stage for the soldiers to see their commanders from the CO down share the risk with them on patrol, and for those commanders to take the lessons learned from participating in platoon and OMLT patrols to generate plans, techniques and structures which addressed both the threat and the environment. It was also critical for the soldiers to believe in what they were doing and to be confident that they were using the best techniques and equipment. The sappers were the hardest hit—the sheer frustration caused by the difficulty of finding the threat combined with the high tempo demanded of them by the situation resulted in exhaustion. The vehicle crews were stretched by the heightened expectation of the threat. The soldiers conducting dismounted patrols from both the OMLT and the combat teams (largely infantry, artillery, engineers and medics) were frustrated by taking casualties from this unseen threat and often being unable to retaliate. However, all took it in their stride, maintaining strong battle discipline. This resilience was incredibly important to the achievement of the mission. Through this effort the battle group maintained dominance of the terrain, refusing to yield initiative to the Taliban, while demonstrating a commitment to the ANA, to the Afghanistan government and to protecting the Afghan people. The perception of our actions was a delicate matter as the national elections loomed in the near future, and the ‘optics’ could influence the confidence of both the ANSF and the local population.

Such experiences early in the tour gave cause to review and to question existing techniques.

Routine and critical reviews of tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) were conducted to enable an adaptive and agile response to changes in the enemy’s methods. The most useful technique to assist in surviving this threat and maintaining momentum was the encouragement of good ‘battle cunning’—to be as unpredictable as possible, and to be capable of rapid and aggressive close combat when required. It was important to not be a slave to prescriptive techniques such as those for obstacle crossing or searching vulnerable points, given the assumption that the enemy was always watching reactions, gauging distances and noting crossing points.

This need is always a challenge when soldiers are trained for and deployed to an unfamiliar environment with a new threat. It takes time for everyone to know the environment well enough to feel confident in adjusting the TTPs from the original template to what is required specific to the situation at that point in time and space. This makes the first weeks of a deployment a dangerous time, but a period of adjustment that everyone needs to pass through in order to be operationally effective. Anything that can be done to advance this level of awareness prior to deployment should be done, and it is not something that is achieved in a single mission rehearsal exercise. It calls for a long period of combined arms mission specific training, with an advanced application of simulation technology. The ADF is a long way from achieving this at present.

This need is always a challenge when soldiers are trained for and deployed to an unfamiliar environment with a new threat.

After the first two months the employment of armoured vehicles in overwatch was reduced to make them less predictable, at times keeping them in dead ground or planning on the use of other direct or indirect fire support (if required) for legs of specific missions. This was particularly important in the Baluchi Valley, where the Taliban had responded to years of Australian TTPs by placing IEDs on most of the favoured support by fire locations.

The techniques used to search for IEDs were amended throughout the deployment as the threat evolved and the battle group expanded into new areas. Insurgent IED TTPs were researched before deploying into new areas, and reviews of their evolving TTPs were conducted continually. If necessary, the combat engineers would amend their search techniques, and advise on amendments to mounted and dismounted patrol techniques to reduce the risk from IEDs. These modified techniques were coupled with the introduction of additional counter-IED equipment, obtained through rapid acquisition following submission of operational user requirements.

One of the greatest concerns as the elections approached was the enemy’s plan to proliferate suicide bombers in populated areas—specifically to target polling centres. The best weapon against this threat is well trained and inquisitive Afghan soldiers. Unfortunately four members of 3rd Kandak were killed and three wounded to a suicide bomber in the Chora Bazaar two days before the elections, when they had their guard down. On the day, however, the ANA were extremely effective. The Taliban were evidently frustrated by their inability to get through the ANA cordons, and resorted to stand off attack with a large number of 107mm rockets being fired in the vicinity of several patrol bases and polling centres throughout the 2nd Kandak area of operations, to no effect. None of the reported suicide bombers in the area were employed and there were no ANSF or civilian casualties.

MRTF-2 experimented with methods of exerting a more persistent dismounted presence within the green zones in order to better protect and influence the local population, and to disrupt and isolate the Taliban. This method was not easy due to the characteristics of the local culture and rural terrain. It took form in the postelection period and was then used to considerable effect in the Mirabad Valley.

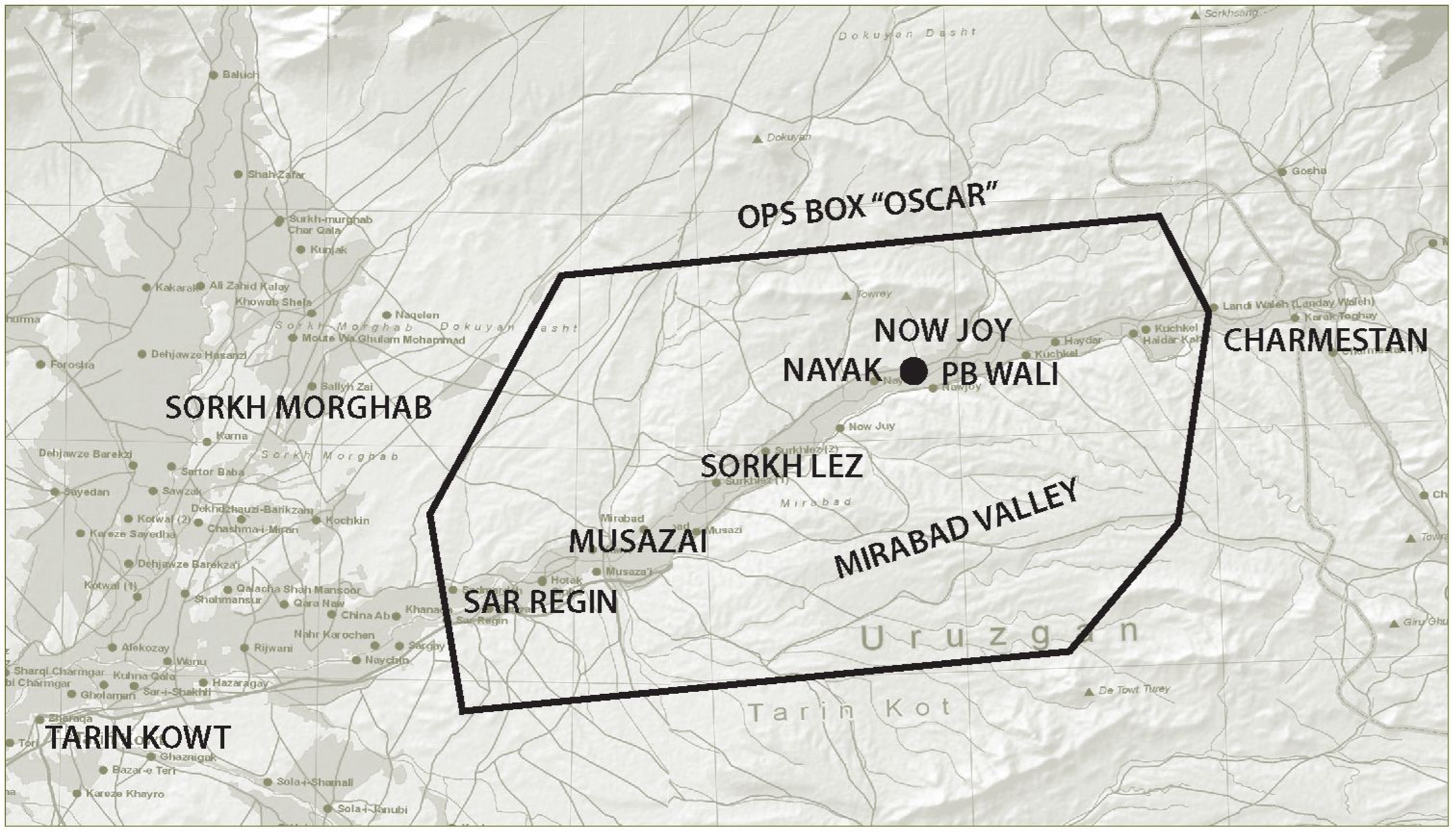

The final cycle of enemy activity was in response to the clearance and domination of the Mirabad Valley in Operation BAZ PANJE (see Figure 3 for the area of operations). Dismounted platoon groups (both Afghan and Australian) were inserted into key locations, where they would ‘rent’ or occupy a local q’ala, and were then sustained in location for up to two months. From these locations section and platoon minus patrols were then able to dominate the terrain, significantly influence and know the locals, and create a substantial dilemma for the Taliban. The enemy were isolated from local support, forced to change their own methods of movement and resupply, and eventually resorted to standoff attack due to the unpredictable nature of movement of the multiple dismounted patrols. The most noteworthy metric was that through the use of these techniques, over fifty caches were discovered within a small area over two and a half months—including anti-armoured weapons, ammunition and large quantities of IED components. The enemy’s preference for Command Wire Improvised Explosive Devices (CWIED) was generally defeated by patrol techniques (fifteen were discovered and disarmed over two and half months) and by the employment of combat engineers in small numbers (often just a pair behind the scouts and commander) on dismounted patrols. The enemy eventually resorted to standoff small arms attack, having lost a large share of their firepower and supplies for the winter months. Thus, on a local level, MRTF-2 seized the initiative by adapting with the threat in a valley which had formerly been regarded a safe haven, and established a persistent ANSF presence to maintain that effect. Such experience of success is essential for the ANSF to become a competent and credible force. Only by building on this experience will the Afghan Army become capable of independently conducting the counterinsurgency.

The enemy were isolated from local support, forced to change their own methods of movement and resupply, and eventually resorted to standoff attack ...

During the operation, Patrol Base Wali was constructed at Now Joy in accordance with Commander 4th Brigade’s intent.8 It was designed to allow ANSF/Coalition forces to easily access the complex terrain without being seen from a distance, enabling our forces to more readily protect and influence the population and to dominate the enemy.

The MRTF-2 approach to mentoring was one of respect first, establishment of rapport second, and then patience in pursuing the outcome. MRTF-2 partnered successfully with 2nd Kandak for the election security operations in August and reinforced ANA primacy at both kandak and brigade level for that operation. OMLT-C developed a system to train and certify the ANA through a series of meaningful intermediary steps between what was at the time referred to as CM (capability milestone) 3 and CM 2.9 OMLT-D then supervised the commencement of 4th Kandak developing their specialist skills post the election, and supported their command of a successful brigade resupply convoy to Kandahar.10 Operation BAZ PANJE saw the integration of 2nd and 4th Kandak elements into Commander 4th Brigade’s main effort in partnership with MRTF-2 to create a new area of operations for the recently trained 3rd Kandak.

The MRTF-2 approach to mentoring was one of respect first, establishment of rapport second, and then patience in pursuing the outcome.

Figure 3. The Area of Operations for Operation BAZ PANJE (September–December 2009)

Two fundamental steps are required to advance the capability of the 4th Brigade to the level Australia seeks to deliver. The first of these is the consolidation of mentoring continuity throughout the brigade.11 This was further enhanced by the subordination of all mentoring tasks across the province to one headquarters—the Mentoring Task Force (MTF). The second is the reorganisation of dispositions on the ground to enable a proper ‘Red-Yellow-Green Cycle’.12 Currently the 4th Brigade is too dispersed to achieve any effective concentration of force, with its troops conducting combat operations on a daily basis and extremely limited opportunities to take leave.

Operational Techniques

The battle group adopted a number of different methods of operation, both in search of the optimal approach to the counterinsurgency and in response to developments in the threat. These modifications to tactics, techniques and procedures were born of the desire to better understand, influence and protect the people, to dominate the enemy and deny them support, and to facilitate the ANA in persistently employing these methods. This section will focus on two primary areas of modification: dispersed operations and influence. Systems and mechanisms were also developed to assist with the short- and long-term health of our soldiers (particularly mental health) and mentoring the ANA (particularly training and certification systems), along with proposals for enhancements to mission specific training and coordination of operational objectives with whole-of-government agencies. These topics are addressed in addition to those described below in the longer LWSC Study Paper No. 321.13

Dispersed Operations

By establishing outposts in q’alas and saturating the area with unpredictable section and platoon group patrols, the section commander was empowered to operate within the platoon commander’s sphere of influence, giving each a measure of autonomy. This enabled MRTF-2 to take the fight to an increasingly elusive and IED-dependent enemy, while also living amongst the people to gain their trust. While Australians have used the technique of dispersed operations in past counterinsurgencies, it was relatively new in South Afghanistan. Due to the level of the threat it had been normal to view the platoon group with its integral vehicles to be the smallest unit of action (with these not remaining in the green zone for any significant period of time). This has generally been the case for conventional and special forces.

While Australians have used the technique of dispersed operations in past counterinsurgencies, it was relatively new in South Afghanistan.

When considering the conduct of dispersed operations in a high-threat battlespace like Afghanistan, it is important to keep in mind that such a technique can only succeed while the enemy is operating at a low level of concentration (which is currently the norm), and the level of threat must be actively monitored for change at all times.14 As with all operational techniques, the required level of force concentration is the judgement of the commander, and the threat needs to be assessed continually with a testing of assumptions. Furthermore, it would appear that it is only when the enemy is reduced to a level of threat that allows the counterinsurgent force to operate in smaller concentrations itself that the population is able to be influenced significantly by the counterinsurgent.

To lodge a platoon in the green zone for up to six weeks, enabling it to dominate a specified area with platoon minus and section patrols, ambushes and observation posts, a number of conditions was required to be set.

- First, the platoon commander needed cash. The green zone is a sea of man-made properties—there is nowhere you can adopt a platoon harbour. The answer is to ‘rent’ a q’ala. This funding line had to be applied for and approved by the national chain of command.

- The second condition was logistics—water and food needed to be plentiful enough to allow them to stay. A large number of water purification kits were used as an emergency measure (noting the irrigation canals were not something soldiers particularly wanted to drink out of) and with money platoons could normally buy good local fruit and bread to supplement their diet.

- The third was the appropriate groupings to fight and win in close combat. Platoon groups took their joint fire teams, combat engineer sections and medic/combat first aiders with them dismounted in the green zone. Availability of offensive support from mortars or direct fire support from aviation (normally US attack or reconnaissance helicopters) or light armoured vehicles in overwatch was carefully coordinated, particularly in the early stages of the clearance before we became familiar with the environment.

- Fourth, communications were essential to ensure fire support, casualty evacuation and resupply. A system was developed using the joint fire team data systems to enable use of data communications. This was particularly useful (when it worked) to send patrol report details (including ‘atmospherics’ of the local population) up the chain of command.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, was access to mobility to insert, resupply and extract these groupings from the green zone. This led to the re-grouping of armoured assets.

Q’alas were selected for occupation by considering the following principles: providing presence and support to permissive areas, demonstrating persistence and resolve to non-permissive areas, interdicting insurgent lines of communication and supply, and disrupting the insurgent network. Targeting known insurgent safe houses and support nodes for occupation as platoon houses presented the advantage of disrupting insurgent freedom of action while demonstrating coalition force presence within a population zone. These counterinsurgency-oriented considerations had to be carefully balanced with the traditional principles of defence and offense.

Targeting known insurgent safe houses and support nodes for occupation as platoon houses presented the advantage of disrupting insurgent freedom ...

The original concept was to regularly move between locations within the green zone every 48 hours or so. Unfortunately the effort of finding a location acceptable to the local population and then establishing supplies was in practice so extensive that platoon houses were secured for significantly longer periods. This involved some risk, but was mitigated by active and disciplined patrolling, and dedicated engagement with the local community to develop high levels of situational awareness and control. During Operation BAZ PANJE, this was proven to be a worthwhile approach, where the benefits outweighed (and mitigated) the risks.

However, as mentioned earlier, it is critical to continually scan the environment and update the commander’s assessment on this balance.15 The experiences in South Afghanistan in 2006 and 2007 suggest that it was necessary to first disrupt the threat by using larger concentrations of coalition forces with greater manoeuvre and firepower, before then employing smaller, more dispersed forces and to introduce greater numbers of mentored indigenous elements. Such progress enables more open engagement and influence with the local population. The use of multiple ‘satelliting’ small team patrols denies the insurgent the ability to coordinate a complex attack and swarm an isolated element.

The ability to conduct the kind of dispersed operations described above rests heavily on the imagination, independence, toughness and resilience of soldiers. In particular, the high calibre of our junior commanders (both JNCOs and officers) enables directive control. Given latitude they positively thrive on the challenge of independence, and the opportunity to employ their battle cunning. This often means that by employing smaller groupings with a smaller, less recognisable footprint, better results are achieved in gaining the initiative by finding more caches or out-manoeuvring the enemy. This has been the experience through several generations of the Australian Army, and soldiers from other nations quickly recognise this when they work closely with the Australians today.

The ability to conduct the kind of dispersed operations described above rests heavily on the imagination, independence, toughness and resilience of soldiers.

It is also important to note the great importance of offensive support and other enablers in allowing such operations to take place. The battle group was allocated joint fire teams on a scale of one per platoon. This enabled each platoon to operate independently from its combat team headquarters and still ensure access to offensive support. Some issues were encountered with this manning as there was no redundancy when platoons were conducting independent operations or in the smaller OMLT locations. This also required careful planning when the platoon was conducting dispersed section operations. They were able to use the high volume of passing coalition air to great effect when required, along with the Dutch 155mm artillery (when in range and available) and the attack aviation capabilities of the US Task Force Wolfpack (who were always keen to assist).

It was of particular importance to be able to rely on the battle group’s organic assets in an emergency or when other coalition assets were tasked elsewhere. These included two (three tube) sections of 81mm mortar (which changed to three sections of two tubes for greater flexibility) and four sniper pairs, as well as personnel trained to employ the .50 cal machine gun and 40mm automatic grenade launcher. Furthermore, MRTF-2 was well equipped with the Type I Light Armoured Vehicle with its 25mm cannon and extremely effective sensors. The mortars and light armoured vehicles proved their worth on election day when the Taliban conducted standoff attacks with 107mm rockets—in three different locations these two weapon systems engaged rocket points of origin to remove the threat. During quieter periods, preserving the employment of mortars (including bedding-in and illumination missions) only for situations of clear and present threat minimised negative effects on the population and reinforced the Taliban’s fear of their reach, lethality and responsiveness.

Having snipers as an organic intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capability who were also capable of surgical kills in the populated green zone was invaluable. They were employed extensively on patrols within the green zone to ‘satellite’ the supported patrol and remain offset from the main body to look for RC/CW IED ‘trigger men’. Snipers were specifically employed for counter-IED operations, and to contribute a layer of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance for major deliberate operations, such as Operation BAZ PANJE. The snipers developed a close relationship with their Dutch counterparts, allowing them to form several combined quads. These were of great utility on deliberate operations as quads were more sustainable and afforded better force protection.

Snipers were specifically employed for counter-IED operations, and to contribute a layer of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance ...

This range of organic assets gave the battle group a degree of flexibility, lethality and range that it could not have achieved by relying on external assets alone.

While experimenting with these dispersed operational techniques in the Baluchi Valley in August and September, many vehicles were not well employed when their dismounts were spending longer periods in the green zone. Furthermore, in the situations where they tried to contribute through provision of overwatch, it was becoming predictable to the Taliban, and a considerable number of vehicles were lost to IEDs in July and August as a consequence. Also, with the addition of an extra combat team and an extra OMLT to the order of battle, the armoured vehicle fleet had become close to 100, and needed to be managed carefully.

For these reasons, MRTF-2 re-grouped16 armoured crews and vehicles (both light armoured vehicle from 2nd Cavalry Regiment and Bushmaster from B SQN 3/4th Cavalry Regiment) into what was called ‘F SQN’ under Captain Craig Malcolm from B SQN, 3/4 Cavalry Regt.17 Patrols from this new sub-unit were tasked with mobility, screening, resupply and support by fire tasks. This resulted in far more efficient usage of vehicles, given that at this stage only a portion of MRTF needed to be lifted at any one time (F SQN was still able to lift up to two thirds of the battle group simultaneously if necessary). This was a different requirement to that during the pre-election period when mobile platoon groups had provided greater flexibility. The change allowed mounted operations to be independent of the dismounted elements simultaneously operating in the green zone. However, platoon groups could still be re-grouped with their original vehicles for roles such as battle group reserve, work site protection or convoy escort that required movement over longer distances.

Some of these ‘modifications’ are far from new, but are tried and proven techniques used by Australian soldiers in previous counterinsurgency campaigns conducted in complex environments. In particular, the conduct of dispersed operations to make the most of capabilities and commanders at section and platoon level were used when appropriate in Malaya, Vietnam, Somalia and Timor Leste. These modifications have better allowed the capture of the initiative in a ‘war amongst the people’ and enabled the success of the ANA in the counterinsurgency.

Influence

The influence line of operations called for a well-synchronised information operations capability with a multi-layered approach. The intent was for information operations to drive the way we operated by manipulating the influence line across all other lines of operations. We adopted the philosophy that all of our actions (including manoeuvre, construction and key leader engagement) would influence perceptions for many different audiences.

The aim was to ensure that we achieved a positive influence that contributed to the achievement of our objectives and mission, without developing unintended consequences. This was facilitated through the development of a system of human analysis so that we better understood who we were influencing, and the employment of a targeting system to allocate priorities to the generation of key effects (both ‘soft’ and ‘kinetic’).

The aim was to ensure that we achieved a positive influence that contributed to the achievement of our objectives and mission ...

The requirement to develop these influence techniques originated in an Afghanistan-focused ABCA (American, British, Canadian and Australian) exercise at Joint Mission Readiness Centre – Hohenfels (JMRC), for which a contingent drawn from 1 RAR and 3 Brigade deployed to Germany in September 2008.18

Within MRTF-2 Headquarters, information operations were run by an infantry SO219 with previous operational experience in psychological operations (PSYOPS), who coordinated the public affairs and PSYOPS elements which were attached from JTF 633. The information operations, with assistance from the S2, contributed to the targeting process for the generation of ‘non-kinetic targets’ such as leadership or powerbrokers to be engaged, or audiences to be specifically influenced. This then registered the influence effects amongst those of the other lines of operation in the commander’s top priorities to compete for time and resources. Thus manoeuvre and other kinetic actions were considered in terms of their information operation (influence) effects, as well as their more direct tactical value.

Examples of this approach ranged from how a large shura was organised, messaged and run, through to impromptu ‘chai sessions’ with local villagers while soldiers were on patrol. The delivery of ‘night letters’ to population centres was occasionally employed to develop the perception amongst the population that the ANA and ISAF ‘owned the night’. These letters would counter insurgent propaganda and spread messages concerning local government initiatives and progress. This technique required immediate follow-up the next morning to reinforce the themes delivered through the night letters and assess any changes to atmospherics.

All planning and coordination measures aside, the most important aspect of influence is to ensure that it is well understood by soldiers on the ground. When other nationalities talk about developing a ‘counterinsurgency based mindset’, Australian soldiers tend to have a more natural feel for what needs to be done. In 2008 the American instructors at JMRC commented on how good the (Australian and New Zealand) soldiers of the ‘ANZAC battle group’ were at switching from a hearts and minds focus to killing the enemy, and then switching back just as quickly to caring for the people. Australian soldiers continue to be the best means of information operations that the Army has. On reflection there are two different levels of information operations: the macro-level of messaging and coordination, where the ADF still needs to develop considerably to catch up with coalition partners; and the micro-level, where those on the ground tend to influence other people as individuals extremely well. This was seen time and again with mentors relating to the ANA, soldiers relating to the local population, and staff relating to coalition partners.

A fundamental component of influence was securing the support of other Coalition elements and convincing them of the need to pursue certain objectives. The battle group commenced the operation with the aim of every commander and staff member seeking out their equivalents in all applicable coalition elements and making a strong effort to get to know them and get on with them in the first month. These relationships were then closely maintained throughout the tour. This effort required additional staff capacity. The creation of an S5 position enabled the headquarters to engage and plan in far more detail, rather than have the S3 distracted by these needs when they should be focused on current operations.

A fundamental component of influence was securing the support of other Coalition elements and convincing them of the need to pursue certain objectives.

The dividends of this policy were substantial: we enjoyed an extremely close relationship with Task Force Uruzgan (our Dutch formation headquarters) and forged close connections with 4th ANA Brigade. These two relationships were fundamental to MRTF-2’s ability to make a significant contribution to the elections and the Mirabad clearance operation in accordance with Australia’s national objectives. It goes without saying that influence through relationships is a critical enabler to success in a coalition environment.

MRTF-2 sought to achieve a far deeper level of understanding of the human dimension within the area of operations in order to achieve a greater influence over the counterinsurgency. This requirement started with questions posed to the S220 during the ABCA exercise in Germany in 2008: ‘who really holds the power at the local level?’, ‘how do we isolate the insurgents from the population?’, ‘which buttons do we need to press to get the right result?’ and ‘what are the second and third order effects of those actions?’ During this activity a targeting cycle, which included information operations, was developed for use in Afghanistan (and continued to develop throughout the deployment). The requirement for greater knowledge of the human dimension eventually led to the development in Afghanistan of a human dimension analysis working group which met daily under the S2, but the team lacked the dedicated intelligence capability to focus on the problem. Therefore a DSTO operational analysis team was requested from JTF 633 on deployment into theatre, and later, a DIO analyst was dedicated to the task. This team set about trying to create a database of human dimension information for MRTF, using Dutch and Australian patrol report data from the previous four years.

The requirement for greater knowledge of the human dimension eventually led to the development in Afghanistan of a human dimension analysis working group ...

This initiative required the feeding of detailed information from the ground through patrol reports. This led to the production of the Human Atmospherics Card by PSYOPS Detachment.21 This laminated palm card had eight standard questions, each of which had three possible answers, to be completed by every patrol regardless of its size. These relatively simple responses resulted in a score that roughly indicated the population’s support for ANA/MRTF presence, which would then be plotted by the intelligence analysts as red, yellow or green dots on a map to indicate levels of permissiveness (‘atmospherics’). This system was used for the first time in Operation BAZ PANJE in the Mirabad Valley, which had not seen a persistent Coalition presence before, making it an excellent opportunity to test and adjust this approach. It was found that the analysis resulted in waves or concentrations of red and green alternating their way up the valley. This knowledge helped with decisions on where to put the patrol base and where to site platoon houses.

In addition to the more obvious contribution to influence made by major works of managed construction in the develop line of operations, there were two adjustments made by the combat engineers of MRTF-2 which significantly enhanced the influence of the coalition.

The engineers established programs to empower local communities to build small local works for themselves, and connected these back to the sponsorship of the Afghanistan government. ‘Community mobilisation’ was a concept developed by Recon Officer 16 CE SQN22 to fill the capability gap between the efforts of the Netherlands provincial reconstruction team and the MRTF-2 Works Team. It was designed to support the development of employment and micro-economies, facilitate skills transfer and invoke community pride by empowering local community leaders to shape their own development in non-permissive rural areas. This technique achieved excellent results on the influence line of operations, particularly in the southern Baluchi Valley and in the Mirabad Valley.

The engineers established programs to empower local communities to build small local works for themselves ...

The Trade Training School23 (TTS) trained local youth in various building trades, providing skilled labour for development. The local ministers for Rural Reconstruction and Development (MRRD) and Energy and Water (MEW)24 are strong supporters of the school, attending graduation ceremonies and providing contracts to local firms who employed TTS graduates. The expansion of this progress to Chora in the second half of the tour, leaving locally trained instructors to continue work in Tarin Kowt, exemplifies the plan to further spread this effect as areas gradually become more permissive. Sorkh Morghab and the Mirabad Valley are future targets for exported TTS courses. This is an extremely important effect in the engagement of the local community to win their support in the counterinsurgency.

A number of techniques employed by MRTF-2 Headquarters25 in the synchronisation of operations at battle group level were particularly beneficial from a commander’s point of view. Having a separate S5 to devote time to planning future operations, but more importantly to influencing the coalition, while the S3 was free to focus on the current battle, was particularly useful in a coalition operation conducted in a high threat environment. Similarly, subordinating influence based effects under the SO2 Information Operations made it easier to coordinate and to synchronise the ‘soft’ effects.

The targeting cycle was developed throughout the tour with the aim of: prioritising resources and actions to achieve all effects in alignment with the commander’s intent; linking lines of operation that were very different in nature; and ensuring the effects produced were indeed the ones of greatest importance, preferably without unintended consequences (particularly those with the potential to undermine the counterinsurgency). The targeting cycle started with a scoping group involving the S2, IO, S3 and S5, and various subordinate specialists under the supervision of the executive officer or battery commander. This group reviewed existing targets for changes in viability or priority, and sought new targets in accordance with the commander’s priorities.

Functional areas within the headquarters were then tasked to develop further detail on the higher priority and most achievable targets. They then reconvened after several days to grade these targets and produce a proposed target list that was presented to the CO in the targeting board. With the CO’s approval and modifications to the required tasks, a fragmentary order was issued tasking subordinate elements, and planning cycles commenced for any major deliberate operations. Some targets generated by the targeting cycle were clearly unachievable by the battle group due to scope or time frame. These targets were passed to TF-U or Regional Command South for action and constantly monitored by the targeting cycle. Such synchronisation is particularly important to maintain direction in a counterinsurgency operation.

This system of coordination was supported by a system of review. None of the techniques described above were derived without mistakes being made (at all levels) and a system of ‘trial and error’ is always important for learning from mistakes and mishaps. Members of the battle group were encouraged to continually review the conduct of activities and the utility of TTPs and standard operating procedures. This feedback was generally channelled through the SNCOs to the RSM, who was responsible for collating lessons learnt, and updating and promulgating revised MRTF standard operating procedures. Battle group after action reviews were conducted after major operations by the XO and the S3.

Members of the battle group were encouraged to continually review the conduct of activities and the utility of TTPs and standard operating procedures.

Having the facility of a ‘CO’s TAC’ group was fundamental to command in a dispersed high-threat area of operations with many small teams operating in comparative isolation. The TAC, as designed by CO MRTF-1, had sufficient firepower, mobility and communications to enable the CO to command from the field. We added an engineer section and occasionally augmented the TAC with an infantry section. This was excellent for battlefield circulation—to visit OMLTs and platoons in isolated locations and participate in activities with them, and fully understand their challenges. Some minor augmentation on top of the crews, CO’s Sig party and Battery Commander’s party for the provision of a control function was required for deliberate operations. With lengthy deliberate operations, consideration does need to be given, however, to the balance between being well informed of your main effort and the conditions on the ground, and gradually becoming dislocated from your main headquarters (in particular ‘high side’ intelligence). Ten days was usually the maximum before links with the main headquarters became an issue, but this judgement depends on the situation. When not being employed by the commander, the TAC troop was capable of taking on other tasks, including that of reserve. This grouping was commanded by a cavalry troop commander.26

Observations

In Afghanistan the green zones are where the population and the threat are concentrated. Within these areas the counterinsurgent must focus on protecting and influencing the population, while simultaneously isolating the threat from the population and reducing their freedom of action. This ‘war amongst the people’ calls for persistent and pervasive dismounted patrolling to dominate the green zone with our Afghan counterparts. This presence develops the confidence and capacity of the ANA, generates trust among the local population in their security forces and their government, and deprives the enemy of the initiative and their support base.

The forces conducting these operations must take calculated risks in order to succeed. In order to remove the enemy’s freedom of action and bring them above the ‘detection threshold’, these operations require relatively small dismounted patrols to saturate the area, often moving large distances on foot in a single day and using difficult routes, to maintain the initiative and maximise their own protection. The size and composition of these patrols will vary depending on the current level of threat in that particular area, and the situation needs to be carefully monitored. If the enemy is manoeuvring in large groupings, they must be dealt with and reduced using concentration of force at the optimum time and place before dispersed operations can be viable.

The forces conducting these operations must take calculated risks in order to succeed.

Such patrols need to be supported by the full combined arms package in order to prevail and overmatch the enemy when they do rise above the detection threshold. This overmatch can often only be provided by offensive support or direct fire support from a distance. Given the constraints placed on offensive support at present, preference will be given to precision guided weapons to minimise collateral damage, but if these are not available, normal indirect fire must be available. All Arms Call For Fire is therefore less likely to be used, but still needs to be available for the last line of force protection. The requirement to generate precision target locations for precision munitions drives an increased demand for Joint Fires Observers (JFO) at lower levels.

Force protection against an adaptive IED threat requires continual modification of techniques coupled with the introduction of new counter-IED technology through either rapid acquisition or purchase of commercial-off-the-shelf equipment in response to operational user requirements. The combination of a continual review of TTPs with adaptive procurement is critical in order to stay ahead of an evolving adversary.

These requirements for successful dispersed operations in a high threat environment rely heavily on the high calibre of our junior commanders and soldiers. Their flexibility, independence and toughness are the backbone of operational capability, particularly in dispersed operations.

Mentoring requires respect, rapport and patience. The generation of confidence and credibility through tactical success is key to establishing a capable new force in a combat environment, and successful partnering is fundamental to achieving these objectives. Development of Afghan Army capability will be more effective if there is a concentration of the ANA above sub-unit level, allowing the generation of a workable red-yellow-green cycle. This may require the handing over of smaller patrol bases to the ANP as they become better established. The achievement of sufficient capability to enable independent indigenous operations is best not considered on a timeline. Mentoring in a counterinsurgency requires a conditions-based approach, endurance and resolve.

Operations to influence the people and dominate the threat in the Afghan green zone generally cannot be conducted from vehicles, because of the canalisation of the terrain and the effects that need to be generated in the populated areas. However, the dismounted element requires the support of vehicles (or aviation, which is harder to attain) for insertion, resupply and extraction. This need is further increased by the extremes of heat in summer and cold in winter. At the same time, activities such as reconnaissance, convoy movement, reserve tasks and direct fire support from the dasht, continue to be heavily dependent on vehicles.

Without a detailed knowledge of the local population—including tribal allegiances and cultural complexities, and a sensitivity to dealing with them—a counterinsurgency force is more likely to turn the local population to the cause of the insurgent. It is therefore extremely important that the force focuses its influence and engagement through a well planned, properly resourced strategy which is informed by human dimension analysis drawn from a reliable database, with regular input from all methods of collection, including patrols, human intelligence and signals intelligence.

The conduct of influence operations can be viewed on two levels—macro (organisational) and micro (personal). It is important that in the quest to solve the issues at the macro level, it’s not forgotten how fundamentally important the micro level is to the achievement of influence, and that Australian soldiers are generally pretty good at it.

The prioritisation and synchronisation of resources to achieve specific effects on extremely different lines of operation can be achieved through a ‘targeting’ process that considers all resources and all effects (both soft and kinetic) required to meet the commander’s intent at the same time. This is particularly helpful for the conduct of counterinsurgency.

If an army loses its capacity to kill, and to win the close fight, it will be unable to exert influence. ‘Soft’ capabilities to win the support of the people in a counterinsurgency environment (to influence, engage, develop and minimise collateral damage) rapidly become irrelevant in an environment such as Afghanistan if they are not underwritten by a tough and agile close combat capability. This requires an extremely flexible mindset amongst all soldiers, and the appropriate type of combat power at their disposal when they require it. This combat power needs to be precise and responsive.

The effect of this kind of combat on soldiers requires that they are better prepared both physically and mentally, that systems are developed to better monitor and care for them while deployed, and that they are given the opportunity to decompress with their team mates in a third country before returning home, where they need to be resourced to rebuild and rehabilitate.

Preparation for such a complex environment demands a significant period of combined arms mission specific training. The time and complexity of this training can be supported by an advanced application of simulation technology to link elements of a decentralised battle group. Participation in a whole-of-government effort requires a coordinated strategy encompassing all agencies for training, planning and conducting operations to achieve effects in the national interest.

Conclusion

MRTF-2 experienced a challenging and successful tour in Uruzgan. This was because of the quality of its people—they were tough, focused, resolute and adaptive. They offered an engaging and population-focused approach to counterinsurgency but always maintained the agility to switch rapidly to aggressive close combat. Through the review of procedures at all levels of the organisation, the battle group developed increasingly successful techniques. The best results were achieved when relatively small dismounted Afghan and Australian elements were fully enabled and empowered to operate amongst the people and dominate the enemy in the green zone. This brought about the success and positive examples required to achieve the optimum mentoring effect. The Australian mentoring mission to build the capacity of the 4th Brigade to the point of independent counterinsurgency operations has shown very encouraging developments to date. However, it has a long way to go before it is complete. This will require considerable endurance, sacrifice and resolve from the Australian Defence Force along with understanding and support from the Australian people. It is important to acknowledge the significant achievements which have been made, and that despite the sacrifice, this is an end worth pursuing.

About the Author

Colonel Peter Connolly trained at ADFA and RMC Duntroon between 1987 and 1990. His operational experience has included deployment to Somalia as a platoon commander in 1993, East Timor as a company commander in 2000, Afghanistan as J3/5 of Regional Command South Afghanistan in 2006, and as Commanding Officer Mentoring and Reconstruction Task Force Two in 2009. Post command he became Director Force Structure Development in Strategic Policy Division. He is now posted to the Pentagon in the Pakistan-Afghanistan Coordination Cell.

Endnotes

1 D Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare - Theory and Practice, Praeger, Washington, 1964, p. 53.

2 Kandak is Afghan for ‘battalion’.

3 Due to a range of manning caps directed for these different elements, no two sub-units within the battle group had the same structure. The original MRTF operational manning document required CT-A to have nine-man rifle and combat engineer sections, inclusive of vehicle crews. For this reason infantry, engineer and artillery soldiers were trained to crew their vehicles within this combat team. If they had been given an armoured corps crew, the section would have been too small (at seven) to do its job effectively on the ground. When CT-B was created it was capped at 120. Because there was some choice in this structure, the option was for two-man armoured corps vehicle crews and eight-man sections in the back—the minimum acceptable size for infantry and combat engineer sections. This avoided having to train more crews at the last minute. Due to its cap, CT-B only had two platoon groups, while CT-A had three. With the late decision by the National Security Committee of Cabinet to send a second OMLT (as MRTF-2 commenced deploying), there were very few options for creating one. The well structured and highly qualified 1 RAR rear details element became the basis for the headquarters of OMLT-D. There was then little option but for 3 BDE to form a composite rear details under 2 RAR. This was not a very satisfactory arrangement for the units involved, but the alternatives were equally problematic.

4 The commanders of these elements were: OC CT-A – Major David Trotter; OC CT-B–Major Damien Geary; OC OMLT-C – Major Brenton Russell; OC OMLT-D – Major Gordon Wing; OC 16 CE SQN – Major Scott Davidson; OC F SQN (Protected Mobility Squadron) – Captain Craig Malcolm; OC CSS COY – Captain Cameron Willett; Battery Commander – Major Peter Meakin; Mortar Sergeant – Sergeant Michael Phillips; and Sniper Supervisor (and ISR Coordinator) – Sergeant Brett Kipping.

5 The author handed over to his successor, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Hocking, as CO of both MRTF-2 and 1 RAR at the end of his posting tenure in Tarin Kowt on 12 December 2009.

6 The local population, the insurgents, the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), the Afghanistan government, the coalition (International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)), and international and domestic (Australian) audiences.

7 Lance Corporal Tim Loch and Sapper Ivan Pavlovic of 3 CER. Both were returned to Australia for treatment, one via Germany.

8 Eight sites were reconnoitered to present options for Commander 4th Brigade prior to the operation. OC 16 CE SQN (Major Scott Davidson) and the S5 (Major Roger McMurray) participated in the recons and provided specialist advice, which was further enhanced by the detailed site recon conducted by the construction troop during the actual operation. The final choice to build north of the river on the edge of the green zone was made by Brigadier General Hamid. It was accessible to the local population, allowing them to provide information and relate to the ANA without being easily identified. This stood in contrast to most other patrol bases in the area of operations which were built on steep hills—easier to defend but isolated from the community, allowing patrols to be easily observed a long time before they entered the green zone, and therefore less capable of dominating the enemy.

9 Warrant Officer Class Two Mark Retallick (CSM OMLT-C) and Major Brenton Russell (OC OMLT-C) developed a four stage approach which included platoon and company collective capability and Kandak planning at all levels as pre-requisites to independent Kandak operations.

10 Operation TOR GHAR 15–19 November 2009 – 4th and 5th Kandak/OMLT-D resupply convoy to Kandahar.

11 The mentoring of headquarters 4th Brigade by the Australian Army commenced informally under MRTF-2, as directed by CJOPS. Major Gordon Wing, Captain Rob Newton, and Warrant Officer Class Two Adrian Hodges of OMLT-D were instrumental in establishing these connections.

12 The concept by which some soldiers can be on leave, some in training, and some conducting operations simultaneously.

13 Peter Connolly, Counterinsurgency in Uruzgan 2009, Study Paper No. 321, Land Warfare Studies Centre, Canberra, 2011, <http://www.army.gov.au/lwsc/SP321.asp>.

14 There were times back in 2006 when a sub-unit was considered the smallest viable unit of action in provinces like Kandahar because the enemy was prepared to swarm in much higher numbers and employ ‘semi-conventional’ tactics. This was particularly an issue for the Canadians in Kandahar and the British in Helmand around the time of Operation MEDUSA in August–December 2006.

15 In the summer of 2006, 3 PARA found that such an approach was not successful when faced with large concentrations of enemy in Now Zad and Musa Qala in Helmand Province. These forces lacked the numbers and fire power to dominate the terrain and the threat, and to influence the population, because the enemy was able to concentrate in far greater numbers relatively quickly.

16 This decision was taken after consultation with the armoured corps officers and SNCOs.

17 With the assistance of experienced members of B SQN and 2 Cav Regt including Captain Rhys Ashton, Warrant Officer Class 2 Glenn Armstrong, Sergeant Haydn Penola, Sergeant Beau St Leone, Sergeant Ben Horton and Sergeant Heath Clayton.

18 Exercise COOPERATIVE SPIRIT in Hohenfels saw the principal staff of MRTF assembled for the first time, in an ‘ANZAC battle group’ consisting of a company of 1 RAR soldiers and a company from 2/1st RNZIR. This was an important test bed for counterinsurgency philosophy. ANZAC forces worked alongside Canadian, British and US forces, all of whom were destined to operate in Afghanistan. Sadly, the then CO of 2 RCR was killed in Afghanistan in early 2010. The new CO of the Welsh Guards (who assumed command after the ex) was killed in Helmand during MRTF-2’s tour.

19 Major Julian Thirkill.

20 Major Nerolie MacDonald from Headquarters 3 Brigade.

21 The Human Atmospherics Card was designed by Warrant Officer Class Two Gary Hopper, who then operated for a long time in the Mirabad Valley as part of an ‘information operations team’ where he tested and adjusted his product.

22 Captain Rod Davis.

23 Under the stewardship of Lance Corporal ‘Spike’ Milligan, who first performed this role as part of RTF-3 in 2008. He drove the expansion of the TTS sphere of influence.

24 Engineers Hashim and Kabir.

25 The principal headquarters staff included: Battle Group XO – Major Anthony Swinsburg; S2 (Intelligence Officer) – Major Nerolie MacDonald; S3 (Operations Officer) – Major Brad Smith; S5 (Plans Officer) – Major Roger McMurray; Information Operations Officer – Major Julian Thirkill; and RSM – Warrant Officer Class One Darren Murch.

26 Lieutenant Andrew Hastie, who was extremely well supported by crew commanders Corporal Nick O’Halloran, Corporal John Wilson, Lance Corporal Chris Cohen and Corporal Dean Lee (Combat Engineer Section Commander).