Abstract

In a little known episode of history, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) seized Christmas Island unopposed on 31 March 1942. Pre-landing air and naval bombardments led the tiny garrison to surrender, but also damaged key facilities, frustrating Japanese efforts to quickly remove the valuable phosphate ore. When Japanese engineers determined the island was not suitable for the construction of an airfield, the occupying force was left solely reliant upon sea lanes of communication, vulnerable to submarine interdiction. A late-1943 submarine attack led to the IJN’s complete withdrawal from its Christmas Island outpost.

On the last day of March, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) captured what would become, if only for a short time, the Japanese Empire’s southernmost outpost.1 The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and IJN had between them invaded and occupied the British territories of Borneo, Malaya and Singapore, as well the Netherlands East Indies. US resistance in the Philippines had been crushed, and the IJN was unchallenged across the western Pacific Ocean. As a prelude to the IJN carrier strike force’s operations in the Indian Ocean, the Imperial General Headquarters ordered the seizure and occupation of the (then) British possession of Christmas Island, 190 nautical miles southwest of Java.

In mid March the IJN Netherlands East Indies Force Commander, Vice Admiral Takahashi Ibō,2 planned the invasion and occupation of the island.3 He planned to secure the island’s rich phosphate ore deposits and to determine the feasibility of establishing a fighter-capable airfield4 there to extend the IJN’s reach into the Indian Ocean, thereby further choking the shipping lanes that linked Australia with India. If it were feasible, the force was to then commence preparatory work for the airfield’s construction. As for the phosphate ore, Christmas Island had long been an important exporter to Japan, so much so that the triangular Islander Jetty was also referred to as the ‘Japanese Pier’.5

Despite its location, Christmas Island had limited strategic potential and was not well defended. By late 1941, the Singapore government, which had jurisdiction over the island territory, had responded to the threat of German raiders—such as the Kormoran, which sank the Royal Australian Navy’s light cruiser HMAS Sydney II off the West Australian coast on 19 November 1941—as well as the growing Japanese menace by establishing a garrison on the island. Given the competing strategic pressures face the British Empire at the time, that force was necessarily a token one, comprising around thirty Sikh soldiers, serving under one British officer and four British non-commissioned officers (NCO). In addition to small arms, this tiny force was equipped with a single 6-inch gun, sited on top of the hill at Smith Point so as to overlook Flying Fish Cove—the island’s only harbour.

Opening Shots

The first visible IJN presence around the islands came on 20 January 1942, when the submarine I-59 torpedoed the 4184-ton Norwegian freighter MV Eidsvold, standing off Flying Fish Cove.6 Heavily damaged, the Eidsvold then drifted and eventually sank off West White Beach. In February, the Garrison claimed to have sunk a Japanese submarine with the Smith Point 6-inch gun, which had been ‘trained at an extreme angle and at close range’ (presumably in Flying Fish Cove) until ‘part of the submarine surfaced and large amounts of oil’ were seen.7 But the counterattack was unsuccessful; I-59 lived to fight another day—if indeed it was her—nor was any other IJN submarine sunk in that area.8

On 9 February, Christmas Island experienced its first air raid, which resulted in the death of three Chinese labourers. Further raids followed on 1 March and 9 March, the latter causing extensive damage to the main town, which was referred to as the Settlement. This was followed on 7 March by an initially cautious and somewhat cursory bombardment of the island’s commercial installations by the battleships Haruna and Kongo.9 Unsure as to whether it might be being used as a submarine or air base, the ships approached from a distance, using their floatplanes to first reconnoiter the island.

On 9 February, Christmas Island experienced its first air raid, which resulted in the death of three Chinese labourers.

After they had determined that the British defences were minimal, the floatplanes dropped 60-kilogram bombs on the island—two of which dropped by one of Kongo’s aircraft destroyed the island’s telegraph station—before directing the battleships’ fire.10 The bombardment appears to have been desultory—Haruna reportedly only fired a total of three 14-inch and fourteen 6-inch rounds—but was nevertheless sufficient to convince the island’s defenders to capitulate.11

As a white flag was raised on the island, the two ships ceased firing and observed as a motorboat, also bearing a white flag, came out to meet them. But as neither the IJN nor the Imperial General Headquarters had planned to occupy Christmas Island at this point—that decision came around one week after the battleships’ bombard- ment—the two battleships departed, leaving the undoubtedly confused defenders behind.12Haruna and Kongo were escorting Rear Admiral Yamaguchi Tamon’s 2nd Carrier Division and had proceeded to Christmas Island at his direction.13 Yamaguchi was renowned as an aggressive commander, who frequently railed against more passive superiors and the bombardment was probably his own initiative, rather than part of a central, strategic plan.

Although the Union Jack was restored to its place on the flagpole,14 the sight of the IJN battleships proved too much for the Sikh soldiers who, joined by the island’s Sikh policemen, mutinied on the night of 10/11 March, murdering the Garrison Commander, Captain Williams and his four British NCOs.15 They then placed the remaining twenty-one Europeans in captivity, until the Japanese landed twenty-one days later.16

Operation X

‘Operation X’, as it was known, was a purely IJN operation without any direct IJA involvement. The sizeable but very much second rate IJN force comprised an 850-strong landing force carried aboard two freighters and escorted by three old light cruisers, two destroyers and two patrol boats, and supported by one tanker.

‘Operation X’, as it was known, was a purely IJN operation without any direct IJA involvement.

Rear Admiral Hara Kensaburō commanded the operation from on board his 16th Cruiser Division flagship, the Natori, accompanied by her sister ship, Nagara. Natori and Nagara were old (both were commissioned in 1922) triple-stack, 5570-ton light cruisers, armed with seven 5.5-inch guns. The third cruiser, Naka, was a slightly younger (1925), four-stacker of similar size (5500 tons) and armament (also seven 5.5-inch guns), and was the 4th Torpedo Flotilla’s flagship. Two destroyers from Naka’s subordinate 9th Destroyer Squadron, the Natsugumo and Minegumo, accompanied the cruisers and provided the primary anti-submarine force.17

These ships set out from Makassar on 25 March,18 and were later joined by the 16th Destroyer Squadron’s Amatsukaze and Hatsukaze. Finally, two small (1162 tons, one 4.7-inch gun) patrol vessels (No. 34 and No. 36),19 escorted the requisitioned freighters, the 5193-ton Kimishima Maru20 and the 7508-ton Kumagawa Maru,21 and the ex-merchantman, converted fleet tanker, the 10,182-ton Akebono Maru.22

The landing party, carried aboard two transports, was drawn from the IJN’s 24th Special Base Unit, based at Ambon. At that time, the 24th Special Base Force had already absorbed into its organisation sailors from the Kure No. 1 Special Naval Landing Force SNLF),23 and was in the process of incorporating the Sasebo No. 1 SNLF.24 It is probably from those SNLF ranks that the 450-strong landing assault group was drawn. Although often referred to as ‘marines’, these landing forces were comprised of sailors who had been provided with a modicum of infantry training and organised into rifle companies.

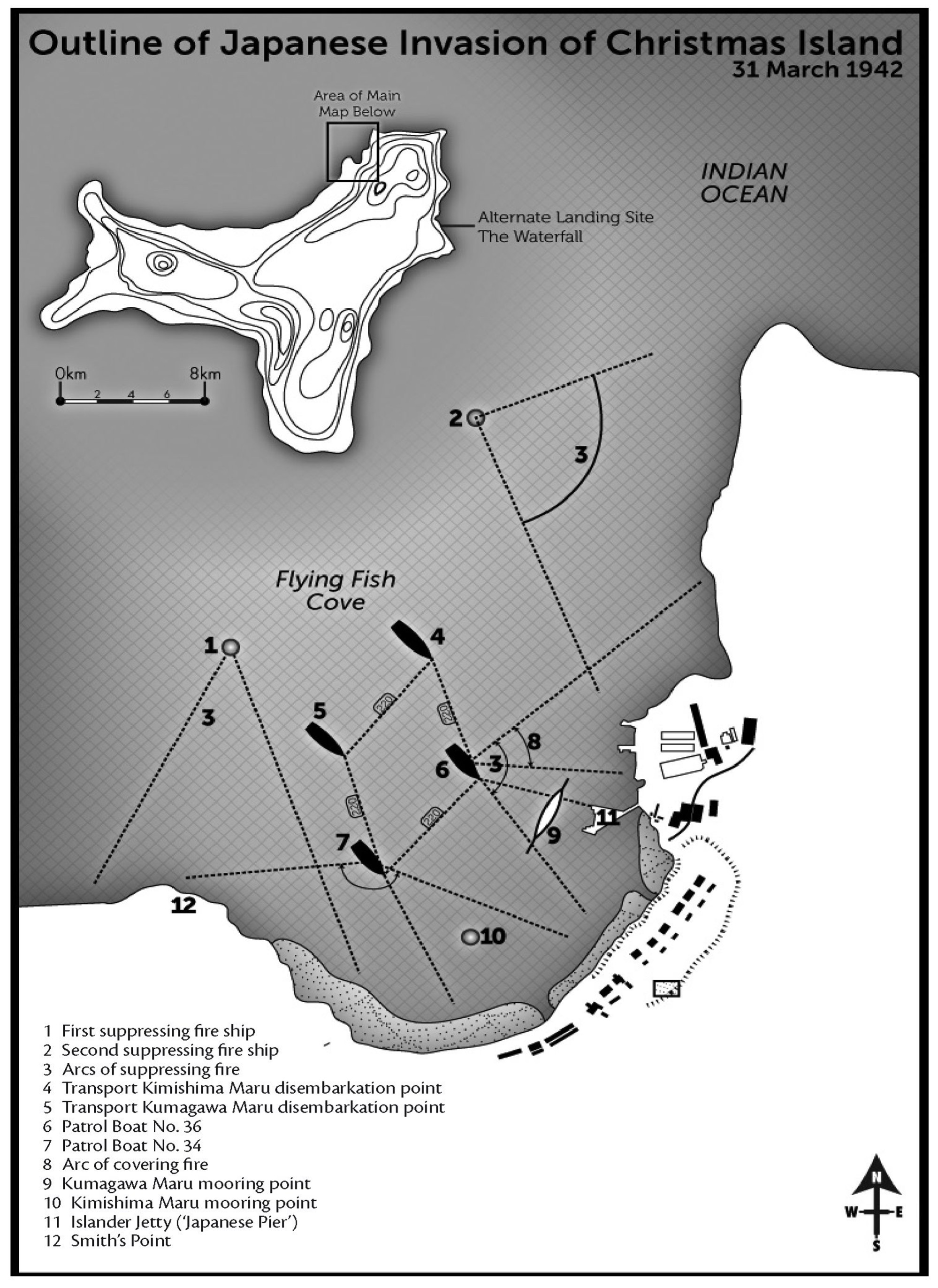

The island’s only harbour at Flying Fish Cove, on the island’s north coast, was selected as the main landing site, with an alternative landing site identified at the waterfall on the northeast coast.25 It was intended from the outset that the landing force would be withdrawn quickly after the island had been secured.26 To garrison the island, 200 sailors from 21st Special Base Unit would man four 12-centimetre naval guns and four 8-centimetre anti-aircraft guns—at least one of which remains— that were to be emplaced on the island.27 They would defend the planned airfield, to be constructed by the 200-strong detachment from the 102nd Naval Construction Force, who would repair the phosphorous mine and loading facilities.

The Landing

Amatsukaze’s captain, Commander Hara Tameichi, described the landing as a ‘simple operation’, the ‘easiest’ he had ever witnessed.28 At 0547 hrs,29 floatplanes from the three cruisers bombed the Settlement near Rocky Point (at the eastern edge of east Flying Fish Cove) and then the 6-inch gun position at Smith Point. At around 0545 hrs, the Naka opened up on the Smith Point gun with her own 5.5-inch guns from a range of about 9000 metres.30 But Naka ceased firing after only three rounds, when a white flag was observed at around 0600 hrs.31 The freighters then moved into their positions in Flying Fish Cove around 0710 hrs, and at around 0745 hrs the landing force commander reported his sailors had reached their initial objectives without encountering any resistance.

Unopposed, the IJN sailors quickly rounded up the Sikh soldiers and local police, with the landing force commander reporting at 1225 hrs that the Settlement had been cleared, the 27-strong Sikh garrison captured, and the Smith Point gun confirmed as inoperable.32 The landing detachment then commenced repairing the phosphate facilities in order to load the precious ore onto their freighters, and started to survey the island.

Torpedoed

Although there was no resistance ashore, the IJN did not have things entirely its own way. At around 0749 hrs on the morning of the invasion, while the Naka was covering the landing, the USN submarine Seawolf made an unsuccessful attack when she fired torpedoes (Japanese records indicate a three torpedo salvo). The IJN escorts counterattacked with six depth charges, and although they claimed to her sunk, having witnessed steam and large amounts of oil on the surface of the water, and having also lost hydrophone contact,33 the Seawolf managed to escape.

Although there was no resistance ashore, the IJN did not have things entirely its own way.

Later, the following morning, at around 0450 hrs, Seawolf lined up a second unsuccessful attack against the Natori. But it was her third attack, at around 1604 hrs, that finally resulted in a single hit on the Naka,34 which:

‘hit smack amidships and broke Naka’s foremast. The impact and explosion left a five-meter hole gaping in its hull. Miraculously, however, not a single crewman was killed.’35

Although Naka had taken on 800 tons of water,36 her compartments held and she was taken under tow by the Natori. Four additional destroyers from the 22nd Destroyer Division were dispatched to protect the crippled cruiser as she was brought first to Bantam Bay (where she arrived on 3 April) and then to Singapore (6 April).37 After making some temporary repairs, Naka returned to Japan two months later where she underwent further repairs and refitting at Yokosuka before eventually returning to service in March 1943, twelve months after Seawolf’s attack.

Withdrawal and Conclusion

Nagara returned to Bantam Bay ahead of Natori, arriving on 2 April, and left for Japan that same day, having handed over escort duties to the four destroyers.38 The following morning (3 April), having loaded as much of refined phosphate ore— around 4000 tons out of the 20,000 tons available—as could be carried was loaded into the freighter,39 the remaining ships at Christmas Island together with most of the IJN landing force sailed for Java. The IJN engineers had determined that the island was not suitable for the construction of an airfield, and so only a small force was to be left behind to maintain order among the island’s subdued inhabitants.

Although the full-scale invasion and occupation had lasted only four days, Japanese ships continued to call at Christmas Island until the 17 November 1943 sinking of the phosphate carrier Nissei Maru (ironically while she was alongside the Japanese Pier)40 by an Allied submarine demonstrated the tenuous nature of the island’s continued occupation.41 In December, the remaining handful of Japanese forces and miners were evacuated to Surabaya aboard the minelayer Nanyō Maru.42

The IJN’s decision to invade and occupy Christmas Island was made following the string of successful advances across South-East Asia. Although the IJN committed an overwhelming force to Operation X, it expected only limited British opposition. That assessment had probably been encouraged by the absence of resistance during the aerial and naval bombardments. Together, these assaults had secured the psychological defeat of the garrison prior to the landing operation itself.

On the other side of the ledger, the bombing and bombardment missions damaged key infrastructure, which impaired the loading of the valuable phosphate ore into the Japanese transports.43 Meanwhile, USS Seawolf’s persistence necessitated the despatch of additional IJN forces, in the form of the destroyers Amatsukaze and Hatsukaze, and the damage she finally inflicted by one torpedo removed from the battle all three cruisers and probably hastened the withdrawal of the remaining covering forces. Combined with the poor showing of the escorts’ anti-submarine warfare efforts, Seawolf’s captain demonstrated the results, both physical and psychological, an aggressive submarine commander could achieve.44

From the outset, Vice Admiral Hara’s orders were that the invasion force be withdrawn quickly, leaving only the engineers and gunners to fortify the island and to prepare an airstrip. When it was decided that construction of an airstrip was infeasible, both the engineers, and the bulk of the gunners appear to have been withdrawn, leaving only the minimum garrison necessary to enforce the Christmas Islanders’ compliance with Japanese rule and to ensure the continued supply of phosphate ore. Although the island remained under Japanese control for almost two years, the occupation was a sideshow during an otherwise dramatic phase of the war. In October 1945, the frigate HMS Rother formally liberated the Islanders and officially restored Christmas Island to British control.

About the Author

Colonel Tim Gellel has enjoyed four postings to Japan, culminating in service as Australia’s Defence Attache to Tokyo from 2008 until 2011. Colonel Gellel developed his interest in Australia and Japan’s shared military history during his time as a student at the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force Command and General Staff College, and later at the National Institute for Defense Studies.

Endnotes

1 At 10°30’ South, Christmas Island lies just south of Indonesia’s southernmost point, the uninhabited Pulau Dana (also Pulau Ndana – south of Roti / Rote Island) which lies at 10°28’ South. In Papua New Guinea, Milne Bay, which is at 10°25’ South, was invaded but not held by Japan.

2 In accordance with Japanese convention, family name precedes the given name in this article.

3 The order for the force was dated 18 March 1942. Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu (Japan National Institute for Defense Studies, War History Department), Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), Vol. 26, Naval Operations on the Netherlands East Indies, Bengal Bay Front (Ran’in, Bengaruwan Hōmen Kaigun Shinkōsakusen), Asagumo Newspapers, Tokyo, Japan, 1969, p. 613.

4 Ibid., p. 614.

5 Because Japan was the Island’s best phosphate customer. J Adams and M Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, Bruce Neale, Canberra, 1993, p. 71.

6 In May 1942, she was renumbered as the I-159.

7 Adams and Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, p. 71.

8 Indeed, I-159 survived the war, and passed into captivity before being scuttled in April 1946. H Jentschura, D Jung and P Mickel (D Brown and A Preston, trans.), Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1992 (1999 edn), p. 170.

9 J Kimata, The Combat History of Japanese Battleships (Nihon Senkan Senshi), Tosho Printing, Tokyo, 1983, p. 123.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid. Figures for Kongo’s ammunition expenditure are not available.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Adams and Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, p. 91.

15 Ibid., pp. 71, 91.

16 Ibid. Most of the European staff and their families had already been evacuated to Perth.

17 2370 tons, six 5-inch guns. Jentschura et al, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945, pp. 147–48.

18 PS Dull, A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1978, p. 103.

19 S Higashi, ‘Zu de miru “Kusentei, Shōkaitei” Hensenshi’ (‘History of the Transition of “Sub-Chasers” and Patrol Boats’) in H Kawajima, Shashin: Nihonsenkan (Warships of Japan in Photographs), Kojinsha, Tokyo, Vol. 13, 1990, p. 167.

20 Jentschura et. al., Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945, p. 276.

21 Ibid., p. 277.

22 Ibid., p. 252.

23 Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu, Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), p. 243.

24 K Shigaki, Kūbo Hiyō Kaisenki (War Diary of the Carrier Hiyō), Kōjinsha, Tokyo, 2002, p. 42.

25 Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu, Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), p. 616.

26 Ibid., p. 614.

27 Adams and Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, p. 75.

28 T Hara, (with F Saito and R Pineau), Japanese Destroyer Captain, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis 2007, p. 84. Although interestingly, the Official History points to Hara’s arrival on the scene as having been at 1830 hrs, well after the landing had been completed. Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu, Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), p. 617.

29 I have converted these times from Tokyo Time (GMT +9 hours), as used in the Senshi Sōsho, to Christmas Island time (GMT +7 hours).

30 Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu, Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), p. 617.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 C Blair, Silent Victory, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2001, p. 190.

35 Hara (with Saito and Pineau), Japanese Destroyer Captain, p. 84.

36 Ibid.

37 Dull, A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945), p. 104.

38 Dull records that Natori returned to Christmas Island on 3 April, but Natori’s Tabulated Record of Movement places her at Bantam Bay that morning, whereas Nagara’s has her arriving at Bantam on 2 April and then departing to sea on the same day. H Idachi, ‘Keijunyōkan Nagara, Isuzu, Natori Kōdōnenpyō’ (‘Tabulated Record of Movements for the Light Cruisers Nagara, Isuzu and Natori’) in Kawajima, Shashin: Nihonsenkan (Warships of Japan in Photographs), pp. 174, 177.

39 The 4000 ton figure is from Adams and Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, p. 71, and is consistent with the capacity of the freighters available. The 20,000 ton figure is drawn from the Japanese landing force commanders report in the Bōei Kenkyūsho Senshishitsu, Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), p. 617.

40 Adams and Neale, Christmas Island: the Early Years, p. 72.

41 Ibid., p. 91.

42 Ibid.

43 Bōei Kenkyusho, Senshishitsu (Japan National Institute for Defense Studies, War History Department), Senshi Sōsho (War History Series), Volume 80 Imperial General Headquarters, Naval General Staff, Combined Fleet [2] (Daihonei Kaigunb;Rengō Kantai [2]), Asagumo Newspapers, Tokyo, Japan, 1975, p. 202.

44 Seawolf’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Warder, claimed to have sunk three of the four light cruisers he believed to be off the island. Blair, Silent Victory, pp. 190–91.