Mobilisation and Australia’s National Resilience

This article explores ways to strengthen Australia’s resilience and facilitate national mobilisation for an environment of increasing threat, major-power conflict and geopolitical competition. It suggests a conceptual model of layered defence as a framework for national resilience and mobilisation, offers a comparative analysis of four distinct approaches (NATO’s resilience agenda, Singapore’s total defence (TD) model, the Baltic states’ comprehensive defence systems, and Taiwan’s overall defence concept (ODC)) and considers ways to incorporate insights from all four approaches into Australia’s ongoing resilience and mobilisation efforts.[i]

The article first analyses Australia’s strategic environment, then develops a framework for national resilience within an overall layered defence construct that is compatible with, though slightly different from, the ‘National Defence’ framework advocated in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review and the 2024 National Defence Strategy and Integrated Investment Program. This generic framework enables comparison among differing resilience and mobilisation systems. The comparative analysis examines four such systems, and was developed through documentary research, engagement with NATO’s ‘Allied Command Transformation’ (ACT) in Norfolk, Virginia; field visits to Singapore, Finland, Estonia, Taiwan and Norway; participation in three NATO resilience seminars held at ACT; and interviews with key personnel from domestic and border security agencies, special operations forces, and territorial defence organisations in relevant countries between 2022 and 2024. The article draws insights from each approach, and from recent events including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, and the conflict in the Middle East, before recommending next steps that policymakers might wish to consider.

Endnotes

[i] This paper is an updated and revised version of a draft paper previously prepared by the author, but never published, in support of the Department of Home Affairs’ National Resilience Task Force in 2023. No funding was received for the earlier research, and the author declares no conflict of interest or other sources of funding.

The analysis suggests the following key judgements:

- Major-power competition, war in Europe and the Middle East, ongoing tension with China, ‘tech wars’ among great powers, economic decoupling among regional blocs and targeting of offshore, cyber and space-based infrastructure all intensify the ‘uncertain and threatening’ environment identified in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update and the heightened risk of conflict noted in Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Reviewand 2024 National Defence Strategy.

- Australian national resilience and mobilisation efforts within this environment will require a more extensive, robust, and better resourced approach than in the past 30 years—especially if Australia seeks to future-proof national resilience and mobilisation against emerging threats. This judgement applies both to external threats and to internal security, countering foreign influence and protecting the civil and human rights of all Australians.

- National mobilisation—for defence, and for a broader range of government objectives—is a whole-of-community effort that will require focused leadership at every level of Australian government and civil society.

- Though not the sole departments involved, Home Affairs and Defence play the critical executive roles across multiple essential functions in resilience, and these departments therefore should be the main effort for national mobilisation, while strengthening the coordinating role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet represents an important supporting effort.

Australia’s Strategic Environment

Already in 2020, the Defence Strategic Update had identified several concerning trends that have since accelerated, contributing to further degradation in Australia's environment. These included intensifying great power competition, increased aggression within the international system, decreased strategic warning time, increasing grey zone activity, increased risk of major war in the Indo-Pacific, and international norms and a rules-based international order under strain.[ii]

NATO’s ‘Resilience Agenda’ identifies similar trends, analysing them through the lens of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA), a framework developed by the US Army War College as a sense-making approach to the post-Cold War environment.[iii] The alliance’s 2030 Capstone Concept, adopted in mid-2021, describes the strategic environment as shaped by VUCA factors and characterised by boundless (geographically unbounded), persistent, simultaneous conflict among state and non-state actors.[iv] Like Australia’s key current strategic policy documents, it identifies rising risk of great power conflict amid disruption and complexity.

Since 2020, the characterisation of Australia’s environment first noted in the Defence Strategic Update has been validated by a series of major disruptions, including:

- state-sponsored cyberattacks on the Australian parliament in mid-2020, followed by significant data breaches at Optus and Medibank reflecting increased threat to Australia’s cyber infrastructure and digital economy[v]

- the COVID-19 pandemic and related trade, transport and supply chain disruptions, along with international and domestic unrest in multiple countries, including Australia, related to governments’ reaction to the pandemic[vi]

- China’s economic bullying and political warfare campaign to punish Australia for seeking an independent investigation of the origins of COVID-19, including export disruptions and ‘fourteen demands’ by a senior Chinese diplomat[vii]

- the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, which undermined US and allied credibility, weakened Western deterrence (increasing the risk of major war), and boosted the morale of terrorist groups worldwide while triggering a humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan and an international surge of refugees[viii]

- Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, resulting in part from weakened Western credibility after the Afghan collapse, which has created the largest, highest-intensity conflict in Europe since the Second World War; triggered global supply chain, commodities and food supply disruptions; caused a major refugee crisis; and reshaped the Eurasian geostrategic order[ix]

- US-Chinese tension escalating through a series of incidents in the South China Sea and East China Sea, around the Philippines and in the Taiwan Strait, with continued growth in Chinese naval and air power, missile capability (including anti-shipping and hypersonic missiles) and space-warfare capabilities, alongside a ‘tech war’ in which the US seeks to disrupt China’s access to advanced semiconductors and artificial intelligence[x]

- increasingly aggressive Chinese incursions into Australian sea and airspace, resulting in Australian ships and aircraft being harassed, targeted using lasers, or shadowed by Chinese air and naval forces in Australia’s exclusive economic zone, while Chinese intelligence-gathering assets frequently encroach on Australian Defence Force (ADF) and multinational exercises[xi]

- the AUKUS agreement, in which governments of both major Australian political parties committed to deepened security relationships and interoperability with the UK and US, along with improvements to Australian defence capability[xii]

- targeting of commercially owned infrastructure, including the destruction by sabotage of the Nordstream 1 and Nordstream 2 pipelines in the Baltic Sea in September 2022, the targeting of space-based communications infrastructure, and a series of attacks on offshore fibre-optic cables and oil and gas platforms[xiii]

- increasing sabotage in multiple countries, targeting railways, factories, bridges, food production, power generation, water purification and other critical systems using kinetic (physical) and cyber means[xiv]

- increased threat from foreign interference, influence and subversion (including disinformation and misinformation) targeting civil society and government, with negative effects on national cohesion and trust in institutions at all levels[xv]

- spillover from the Israel-Gaza conflict and wider Middle Eastern theatre, including increased terrorist threat within Australia and supply chain disruption following efforts by Ansarallah (Houthi) forces in Yemen to block the Red Sea to commercial shipping traffic.[xvi]

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review took account of these developments (with the exception of the Middle East conflict, which had not yet escalated when the document was published) identifying a global strategic environment with significantly heightened risk of conflict. The review noted:

Australia’s strategic circumstances and the risks we face are now radically different. No longer is our Alliance partner, the United States, the unipolar leader of the Indo-Pacific. Intense China-United States competition is the defining feature of our region and our time. Major power competition in our region has the potential to threaten our interests, including the potential for conflict.[xvii]

Noting that emerging technologies enable hostile actors to seriously threaten Australia without invading our territory, and that our traditional reliance on geography and strategic warning time no longer applies, the review concluded that Australia’s current regional circumstances are characterised by major-power competition, coercive tactics, an accelerating and non-transparent expansion of military capabilities, militarisation of emerging and disruptive technologies, nuclear weapons proliferation, and increased risk of miscalculation or misjudgement.[xviii]

While Defence was analysing the environment for the 2020 and 2023 reviews, the Department of Home Affairs also initiated a range of efforts on homeland security and critical infrastructure. However, the Commonwealth Government has issued no whole-of-government strategy since 2013’s Strong and Secure: Australia’s National Security Strategy, partially updated in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.[xix]

Strong and Secure identified several national security risks, including espionage and foreign interference, instability in developing and fragile states, malicious cyber activity, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, serious and organised crime, state-based conflict or coercion significantly affecting Australia’s interests, and terrorism and violent extremism. Based on that risk analysis, it enumerated eight pillars of Australian national security, as follows:

- Countering terrorism, espionage and foreign interference

- Deterring and defeating attacks on Australia and Australia’s interests

- Preserving Australia’s border integrity

- Preventing, detecting and disrupting serious and organised crime

- Promoting a secure international environment conducive to advancing Australia’s interests

- Strengthening the resilience of Australia’s people, assets, infrastructure and institutions

- The Australia–United States alliance

- Understanding and being influential in the world, particularly the Asia-Pacific.[xx]

While the risks and pillars identified in 2013 remain relevant, their relative importance has shifted as a result of the developments noted above. As Bruce Jones noted in 2020, global affairs at the broadest level have been unsettled by China’s rise to become the world’s second-largest economy, largest energy consumer and second-largest defence spender. Meanwhile, Beijing’s increasingly assertive posture is intensifying a pattern of great power competition.[xxi] These developments have increased the risk of major conflict in Australia’s region, while simultaneously increasing the threat of foreign interference, cyber-attacks, sabotage of Australian assets and infrastructure, and disruption of Australia’s trading, energy supply and economic interests.

The intensified war in Ukraine since February 2022 has dominated security thinking within NATO and, to a lesser extent, in Washington DC. However, as the head of the UK’s Security Service (MI5), Ken McCallum, noted in 2020:

if the question is which countries’ intelligence services cause the most aggravation to the UK in October 2020, the answer is Russia. If, on the other hand, the question is which state will be shaping our world across the next decade, presenting big opportunities and big challenges for the U.K., the answer is China. You might think in terms of the Russian intelligence services providing bursts of bad weather, while China is changing the climate.[xxii]

More recently, in February 2023 the US intelligence community assessed that:

while Russia is challenging the United States and some norms [in a regional conflict in Ukraine], China has the capability to … alter the rules-based global order in every realm and across multiple regions, as a near-peer competitor.[xxiii]

Each of these assessments emphasises the distinction between acute, urgent crises and longer-term but less obvious shifts in the background environment—McCallum’s ‘weather’ versus ‘climate’ metaphor is particularly apt. Addressing this full range of threats, in a timely manner, involves developing a robust model for national resilience and national mobilisation within an integrated overall defence and security framework.

National Resilience in Context

We can understand national resilience within a broader construct of comprehensive (sometimes termed ‘total’) defence, in which national security derives from the integrated effects of multiple activities and institutions across a series of layers, building on each other.[xxiv] Underpinning this ‘layered defence pyramid’ (but not considered in detail in this analysis) lies a set of national policies to enhance cohesion, prosperity and state effectiveness.[xxv] These include industrial, critical technologies and commodities, entrepreneurship, innovation, scientific research and development, energy, health, education, trade, telecommunications, transport and space policy.[xxvi] This policy baseline represents the platform on which national security capabilities are built, and is fundamental to national strategy.[xxvii]

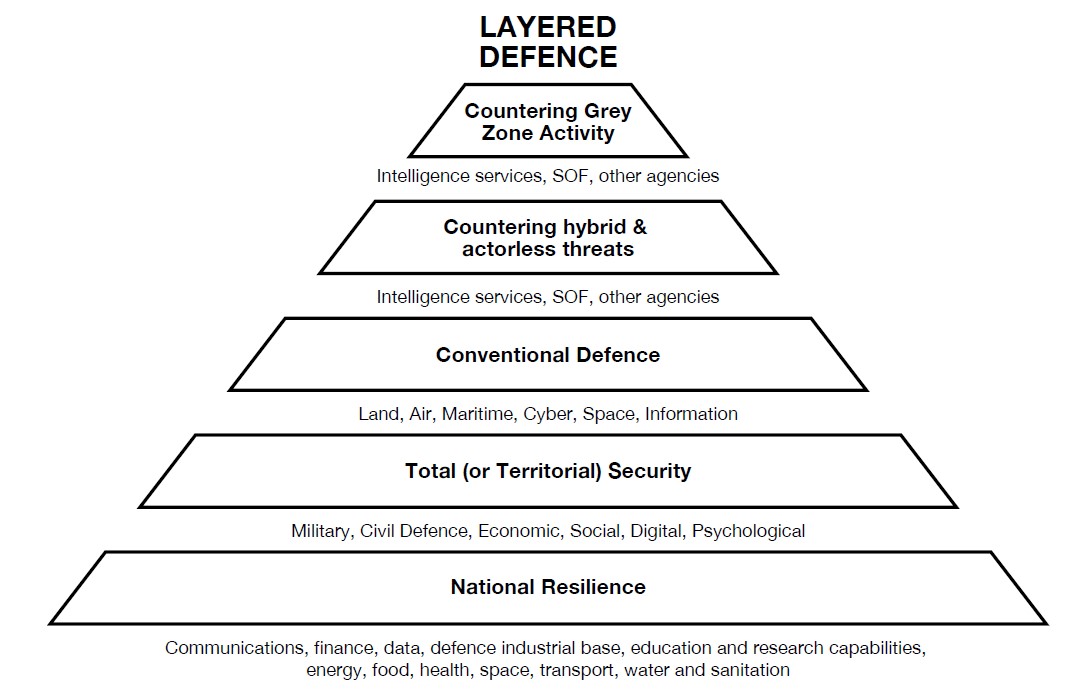

Layers within the pyramid include national resilience, total (or territorial) security, conventional (sometimes ‘traditional’) military capabilities, countering hybrid and ‘actorless’ threats (pandemic disease, climate change, natural disasters)[xxviii] and grey zone activity. The higher up the pyramid, the tighter the control exercised by national authorities, and the greater the role of central (as distinct from local and state) government. Higher placement on the pyramid does not imply greater importance, risk, or expenditure—arguably, the lower levels are the most important. Rather, each layer builds on, draws resources from, and enhances the effects of the layers beneath it. The framework can be represented graphically as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Layered defence within a comprehensive (total) defence framework

Within this construct:

- National resilience forms the base on which all other activities build. While nations and organisations define resilience differently (as discussed below), most include some or all of the categories of communications, finance, data, health, energy, food and water and transport in their frameworks.

- Total defence builds on national resilience and includes military and non-military territorial defence organisations, border security, customs and excise, biosecurity, civil defence (including emergency services), environmental protection, critical infrastructure protection (physical and digital) and, in some countries, social cohesion and psychological preparation of the population.

- Conventional defence includes military activities to defend the nation, its territory and population, and its broader interests. It includes operations in the land, sea, air, space, cyber and information domains and is led by Defence and supported by Home Affairs, the intelligence community and law enforcement.

- Countering hybrid and actorless threats deals with terrorism, insurgency, people-smuggling, narcotics trafficking, modern slavery and other serious organised crime, along with threats to the environment and public health from natural disasters, disease, weather and climate. The intelligence community, special operations forces and other specialised agencies often take the lead at this level, supported by conventional defence and home affairs organisations.

- Grey zone activity is action beyond the realm of normal peacetime interaction but below the threshold of armed conflict. As the upper level of the layered defence construct, it builds on all capabilities from the other layers. Many nations, and organisations such as NATO and the EU, have published defensive strategies or established centres of excellence for countering grey zone activity. Several also conduct offensive operations in the grey zone.

Roles of Defence and Home Affairs

The departments of Home Affairs and Defence play a role at every level of this layered construct and are the two most important agencies in executing the Commonwealth Government’s resilience and mobilisation efforts, while the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet plays a critical coordinating role. Home Affairs’s core business lies in the resilience layer, with the department leading most inter-agency efforts at this level, while other departments play supporting roles. At the level of total defence, Home Affairs and Defence operate together, each leading specific tasks while supporting other agencies on others. Defence takes the lead in conventional defence, supported by Home Affairs and others, while at higher levels of the construct each department conducts specialised activities to support whole-of-government objectives, in conjunction with other agencies. Within Defence, the ADF plays a critical role in executing operations at each level of the construct, while also providing a recruiting and mobilisation base that enables its own activities but also those of other departments. The national industrial base, along with financial, communications, scientific and technological research, education, health and transport systems, provides the firm platform on which higher levels of the construct rest, while ultimately also providing the motivation for national mobilisation and resilience, since these systems form key parts of the Australian society that is being defended.

National Mobilisation within Layered Defence

This layered defence construct is not specific to Australia. Rather, it is a generic framework that allows comparison of capabilities and concepts across multiple countries and organisations (discussed in Part 2). It represents a comprehensive, enduring, flexible framework for national resilience and defence across multiple threat levels over time, rather than a wartime posture. As the strategic environment progresses from normal or steady-state peacetime cooperation and competition, through pre-crisis, crisis, conflict and war, the necessary level of national mobilisation changes accordingly. Mobilisation involves trade-offs between readiness posture (which is costly to maintain) and strategic warning time. The decision to mobilise—if taken under pre-crisis or crisis conditions—can itself precipitate a conflict, as seen most famously in the European powers’ mobilisation on the eve of the First World War or, more recently, Ukraine’s January 2022 decision not to mobilise lest this should provoke a direct Russian invasion.[xxix] Conversely, failure to mobilise in time can leave a nation unprepared and vulnerable to strategic surprise.[xxx]

Over much of the last five decades, Australian planners assumed a 10-year strategic warning window for major inter-state conflict, allowing the nation to maintain peacetime mobilisation levels on the assumption that it would have a decade to prepare for war. As a result, problems of mobilisation—particularly, rapid expansion of the ADF and the supporting assets and infrastructure needed to enable such an expansion—were under-emphasised. One of the most important observations of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, therefore, was the judgement that the nation is now inside that 10-year warning period and must now raise its mobilisation posture (and, by extension, improve national resilience). The 2023 Defence Strategic Review went further, noting that loss of warning time ‘has major repercussions for Australia’s management of strategic risk. It necessitates an urgent call to action, including higher levels of military preparedness and accelerated capability development’.[xxxi] The 2024 National Defence Strategy reaffirmed these judgements, noting that ‘Australia no longer enjoys the benefit of a ten-year window of strategic warning time for conflict’ and that since 2023, ‘our strategic circumstances have continued to deteriorate, consistent with the trends the Defence Strategic Review identified’.[xxxii]

Acknowledging that a 10-year warning period no longer exists represents a significant departure from 30 years of strategic practice. It also departs from Australia’s post-Cold War focus on threats from weak states, failing states and non-state actors—and hence on small-scale, long-duration coalition expeditionary operations, in support of alliance partners, in distant theatres. This focus resulted in under-resourcing of resilience capabilities, and the atrophy of national mobilisation planning. Most importantly, the acknowledgment that Australia can no longer rely on a 10-year warning time underscores the need for a mindset shift toward self-reliant national defence, and the ability to mobilise rapidly and effectively in the face of a deteriorating strategic environment.

For Australia as for other countries, the COVID-19 pandemic also represented a wake-up call. It highlighted the need for resilience against actorless threats, alongside national cohesion, intergovernmental coordination at local, state and Commonwealth levels, improved effectiveness across a range of services, resilience against bullying by a great power adversary, and supply chain, food and energy resilience.[xxxiii] During the same period, a series of natural disasters—bushfires and flooding in Australia, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions across the region—required the nation to mobilise around shared resilience goals. Key questions arising from this experience include the following:

- What is the optimal division of responsibilities among local, state and Commonwealth governments? Is the existing allocation of roles appropriate?

- Should decision-making adaptations such as National Cabinet be extended or adapted into permanent national security institutions?

- In emergencies that do not justify use of the Commonwealth’s constitutional defence power, who has legal authority? How should that authority be coordinated among states and territories, and among Commonwealth agencies? Do existing arrangements scale appropriately for higher-level threats?

- Does the use of the ADF rather than civilian agencies for COVID-19 or other emergencies devalue civilian agencies? Does it overstretch Defence, or deplete resources better used higher in the layered defence pyramid?

- Which departments should have command and control (C2) authority, as distinct from execution responsibility, and under which circumstances?

- How has recourse to Defence for internal security efforts affected public trust in the military, and how has it affected training and warfighting capability?

- How has use of Defence assets for logistics, transport and public safety affected Defence’s readiness for its core warfighting functions, and how has it influenced investment in other agencies?

- What is the appropriate role within national resilience for civil society, including organisations such as the Mindaroo Foundation; the Australian Resilience Corps; Team Rubicon; the Returned and Services League; and veterans’, religious and volunteer groups, charities and philanthropic foundations?

- How can a multiplicity of assets and organisations at every level of civil society best be coordinated—as distinct from controlled, since these are non-government assets—in order to achieve synergy and efficiency?

- Last, but arguably most importantly, how can the civil rights, democratic freedoms and human rights of all Australians be respected and safeguarded even under conditions of national emergency and patriotic dissent?

These questions were partially addressed in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review and 2024 National Defence Strategy. However, in the absence of a whole-of-government national security strategy—or a detailed, robust and regularly updated plan for national mobilisation—an approach that focuses primarily on the role of the Department of Defence and the ADF can, by definition, only be a partial solution. Even following the excellent work of the Department of Home Affairs’s national resilience task force, addressing these broader questions remains an important interdepartmental requirement, as well as a crucial national conversation, if recent crises are to help improve national resilience and mobilisation capacity for the era of heightened threat in which Australia currently finds itself.

Endnotes

[ii] Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Update 2020 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020), pp. 11–17.

[iii] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Command Transformation (NATO ACT), Resilience Symposium, at: https://www.act.nato.int/resilience.

[iv] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO 2030 Factsheet (NATO ACT, June 2021), at: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/6/pdf/2106-factsheet-nato2030-en.pdf.

[v] See Georgia Hitch and Andrew Probyn, ‘China Believed to Be behind Major Cyber Attack on Australian Governments and Businesses’, ABC News, 18 June 2020, updated 14 July 2020, at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-19/foreign-cyber-hack-targets-australian-government-and-business/12372470.

[vi] For a partial analysis see Alan W Cafruny and Leila Simona Talani (eds), The Political Economy of Global Responses to COVID-19 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

[vii] See Jonathan Kearsley, Eryk Bagshaw and Anthony Galloway, ‘”If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy”: Beijing’s Fresh Threat to Australia’, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 November 2020, at: https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/if-you-make-china-the-enemy-china-will-be-the-enemy-beijing-s-fresh-threat-to-australia-20201118-p56fqs.html.

[viii] See David Kilcullen and Greg Mills, The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan (London: Hurst & Co., 2021)

[ix] Among multiple (and conflicting) analyses see Lawrence Freedman, Modern Warfare: Lessons from Ukraine (Sydney: Lowy Institute, 2023); Glenn Diesen, The Ukraine War and the Eurasian World Order (Atlanta GA, 2024); and David Kilcullen and Greg Mills, The Art of War and Peace (Cape Town: Penguin Random House, 2024).

[x] See U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington DC, 2023), at: https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

[xi] See Shaimaa Khalil, ‘How Australia-China Relations Have Hit “lowest ebb in decades”‘, BBC News, 11 October 2020, at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-54458638.

[xii] See ‘Joint Leaders’ Statement on AUKUS’, Prime Minister of Australia website, 14 March 2023, at: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/joint-leaders-statement-aukus.

[xiii] For two among many recent analyses see Helga Kalm, NATO’s Path to Securing Undersea Infrastructure in the Baltic Sea (Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2024), at: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/05/nato-baltic-sea-security-nord-stream-balticconnector?lang=en; and Christian Bueger and Tobias Liebetrau, ‘Critical Maritime Infrastructure Protection: What’s the Trouble?’, in Marine Policy 155 (2023): 105772, at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X23003056.

[xiv] See Souad Mekhennet, Catherine Belton, Emily Rauhala and Shane Harris, ‘Russia Recruits Sympathizers Online for Sabotage in Europe, Officials Say’, Washington Post, 10 July 2024; and ‘Russia Is Ramping up Sabotage across Europe’, The Economist, 12 May 2024.

[xv] See Office of National Intelligence (ONI), ‘ASIO Annual Threat Assessment 2024’, ONI website, 28 February 2024, at: https://www.oni.gov.au/asio-annual-threat-assessment-2024.

[xvi] See Liam Stack, Mike Ives and Gaya Gupta, ‘Tensions Spilling over from Gaza to Red Sea Escalate’, New York Times, 16 December 2023; and Noam Raydan, ‘Houthi Ship Attacks Pose a Longer-Term Challenge to Regional Security and Trade Plans’, Policywatch 3890 (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), 26 June 2024, at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/pdf/view/18828/en.

[xvii] Department of Defence, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 23.

[xviii] Ibid., p. 28

[xix] Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Strong and Secure: Australia’s National Security Strategy (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2013), p. 2.

[xx] Ibid., p. 15.

[xxi] Bruce Jones, China and the Return of Great Power Strategic Competition (Brookings Institution, 2020).

[xxii] Dominic Nicholls and Robert Mendick, ‘MI5 Chief: Russia’s Intelligence Services Provide “bursts of bad weather, China is changing the climate”‘, The Telegraph, 14 October 2020, at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/10/14/mi5-chief-britain-faces-nasty-mix-threats-state-backed-hostile/.

[xxiii] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community (Washington DC: U.S. Government, February 2023), p. 3.

[xxiv] For the doctrinal and theoretical underpinning of layered comprehensive (‘total’) defence see NATO Special Operations Headquarters, Comprehensive Defence Handbook, Vol. 1 (December 2020), pp. 17–18, 21, 34ff.

[xxv] Jan Angstrom and Kristin Ljungkvist, ‘Unpacking the Varying Strategic Logics of Total Defence’, Journal of Strategic Studies, online, 27 September 2023, at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/01402390.2023.2260958?needAccess=true.

[xxvi] Joaquim Soares, ‘A Literature Review on Comprehensive National Defence Systems’, in NATO Science and Technology Organization, Conceptual Framework for Comprehensive National Defence System (2021), at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joaquim-Soares-3/publication/349099458_A_Literature_Review_on_Comprehensive_National_Defence_Systems/links/60ed4ff116f9f313007c7481/A-Literature-Review-on-Comprehensive-National-Defence-Systems.pdf.

[xxvii] Ieva Berzina, ’From “Total” to “Comprehensive” National Defence: The Development of the Concept in Europe’, Journal on Baltic Security 6, vol. 2 (2020): 1–9.

[xxviii] See Morgan Bazilian and Cullen Hendrix, ‘An Age of Actorless Threats: Rethinking National Security in Light of COVID and Climate’, Just Security, 23 October 2020, at: https://www.justsecurity.org/72939/an-age-of-actorless-threats-re-thinking-national-security-in-light-of-covid-and-climate/.

[xxix] For the classic account of mobilisation in 1914 see Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August: The Outbreak of World War I (New York: Random House, 1962), Kindle edition locations 1560–1579. For Ukrainian reluctance to fully mobilise in 2022 see Alexander Baunov, ‘As Ukraine Escalation Peaks, What’s the Logic on Both Sides?’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace website, 16 February 2022, at: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/02/as-ukraine-escalation-peaks-whats-the-logic-on-both-sides?lang=en¢er=russia-eurasia.

[xxx] For an overview of historical cases of Australian mobilisation see Peter Layton, National Mobilisation during War: Past Insights, Future Possibilities, National Security College Occasional Paper (Canberra: Australian National University, August 2020), at: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/f6268d5a-6e66-4e58-b559-b0add582b9ef/content.

[xxxi] Defence Strategic Review 2023, p. 25.

[xxxii] Department of Defence, National Defence Strategy 2024 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024), pp. 5, 11.

[xxxiii] The term ‘adversary’ in this context refers to a potential future enemy, rather than a current one.

The analysis suggests the following key judgements:

- Major-power competition, war in Europe and the Middle East, ongoing tension with China, ‘tech wars’ among great powers, economic decoupling among regional blocs and targeting of offshore, cyber and space-based infrastructure all intensify the ‘uncertain and threatening’ environment identified in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update and the heightened risk of conflict noted in Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Reviewand 2024 National Defence Strategy.

- Australian national resilience and mobilisation efforts within this environment will require a more extensive, robust, and better resourced approach than in the past 30 years—especially if Australia seeks to future-proof national resilience and mobilisation against emerging threats. This judgement applies both to external threats and to internal security, countering foreign influence and protecting the civil and human rights of all Australians.

- National mobilisation—for defence, and for a broader range of government objectives—is a whole-of-community effort that will require focused leadership at every level of Australian government and civil society.

- Though not the sole departments involved, Home Affairs and Defence play the critical executive roles across multiple essential functions in resilience, and these departments therefore should be the main effort for national mobilisation, while strengthening the coordinating role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet represents an important supporting effort.

Using the layered defence construct, described in Part 1, as a common analytical framework, this section offers a comparative analysis of four resilience and comprehensive defence approaches: NATO’s resilience agenda, Singapore’s TD construct, the Baltic states’ total resistance model and Taiwan’s ODC.

NATO’s Resilience Agenda

NATO resilience requirements (mandated under Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty) include the twin components of military capacity and civil preparedness. Each NATO nation is obliged to maintain its own national resilience and mobilisation capability. In effect, collective defence commitments under Article 5 of the treaty serve to complement self-reliance commitments from each nation to its allies under Article 3. At their 2016 Warsaw summit, NATO leaders committed to enhancing resilience across seven baseline requirements.[xxxiv] These are:

- Assured continuity of government and critical government services

- Resilient energy supplies: back-up plans and power grids, internally and across borders

- Ability to deal effectively with uncontrolled movement of people, and to de-conflict these movements from NATO’s military deployments

- Resilient food and water resources: ensuring supplies are safe from disruption or sabotage

- Ability to deal with mass casualties and disruptive health crises: ensuring civilian health systems can cope and sufficient medical supplies are stocked and secure

- Resilient civil communications systems: ensuring telecommunications and cyber networks function even under crisis conditions, with sufficient back-up capacity (Note: in November 2019, NATO defence ministers stressed the need for reliable communications systems including 5G, robust options to restore these systems, priority access to national authorities in times of crisis, and thorough assessments of all risks to communications systems)

- Resilient transport systems: ensuring NATO forces can move across alliance territory rapidly and that civilian services can rely on transport networks, even in a crisis.[xxxv]

This framework represents a recognition that civil preparedness and resilience, while well-resourced during the Cold War, became less effective after 1991. Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 prompted a reassessment, leading to reinvestment and increased resilience efforts led by the international defence staff and NATO’s ACT. The principal mechanisms for advancing NATO resilience have included high-level commitments at NATO summits in 2016, 2019 and 2022; creation of a NATO resilience symposium that has met regularly since 2019 to pursue data sharing, common standards and collaborative resilience; and capability development through NATO-accredited centres of excellence (COEs). COEs are international military organisations that train and educate leaders and specialists from NATO member and partner countries, engage in doctrine development, and work on lessons learned, interoperability and experimentation.[xxxvi] NATO-accredited COEs support military and civil resilience capabilities, including countering improvised explosive devices, C2, cooperative cyber defence, crisis management and disaster response, energy security, defence against terrorism, joint chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence, and stability policing.[xxxvii] They provide trained personnel, research, and common concepts, doctrine and procedures across the alliance.

In addition, although not currently a NATO COE, the European COE for countering hybrid threats, in Helsinki, is jointly funded by the European Union, specific nations and NATO. The centre was established in 2017 by a network of nine participating nations, along with multinational institutions within NATO and the EU.[xxxviii] Its establishment reflects the heightened focus on resilience and great power competition among Nordic and Baltic nations following Crimea, and the status of Finland as an EU member but not (at the time) a NATO ally. The accession of Finland to the alliance in 2023 has not yet resulted in the counter-hybrid COE becoming a NATO COE, but its focus is likely to remain on cross-cutting issues including legal resilience, deterrence and cyber resilience.

While initially emphasising civil preparedness, NATO’s resilience framework was adapted in 2019 to sharpen its focus on communications systems, cybersecurity and information security.[xxxix] It has continued to evolve. For example, COVID-19 exposed nations’ reliance on extended supply chains for critical commodities, prompting greater emphasis on supply chain resilience. All NATO-accredited COEs were tasked to develop lessons learned from the pandemic, under a process coordinated by NATO’s Joint Analysis Centre for Lessons Learned, located in Lisbon.[xl] Likewise, the alliance noted the need to improve resilience against ‘invisible’ (i.e. actorless) threats[xli] and announced a Strengthened Resilience Commitment in June 2021.[xlii] This commitment, for the first time, introduced the concept of ‘democratic resilience’, noting ‘increasingly pervasive hostile information activities, including disinformation, aimed at destabilising our societies and undermining our shared values; and attempts to interfere with our democratic processes and good governance’.[xliii] It informed a proposal to establish a centre for democratic resilience focused on countering misinformation, disinformation and foreign influence. This proposal has been controversial among member nations on civil liberties and national sovereignty grounds, and has not been implemented so far.[xliv]

NATO’s Resilience Framework: Implications for Australia

In a broad sense, Australia can learn much from NATO’s approach to resilience and mobilisation, particularly the alliance’s strengthened resilience commitment since 2021 (in effect, a partial mobilisation in the face of Russia’s build-up ahead of the invasion of Ukraine). Simply having a stated set of resilience priorities—centrally updated, furthered by a coordinating body and advanced through a network of capacity-building centres—helps focus efforts. NATO’s multinational character means that resilience rests on intergovernmental data sharing, while in Australia’s case the states and territories could benefit from aligning with Commonwealth priorities, while drawing on national resources.

Australia’s critical infrastructure legislation shows some overlap with NATO’s resilience agenda. The Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Bill 2021identified 11 critical sectors: communications; financial services and markets; data storage or processing; defence industry; higher education and research; energy, food and grocery; health care and medical; space technology; transport; and water and sewerage.[xlv] Australia’s policy includes areas (space technology, higher education and research, defence industry, and financial services and markets) not covered in NATO’s framework. Likewise, two NATO functions—continuity of government and control of mass population movement—are not explicit in Australia’s legislation, though they are covered under existing policies. It is of course worth noting that critical infrastructure protection, mobilisation, and national resilience are different though overlapping categories.

A major omission in NATO’s framework is supply chain resilience. NATO’s pandemic lessons learned process has not yet resulted in an updated framework to include supply chain resilience as an additional, eighth baseline requirement. In Australia’s case, the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (led by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in cooperation with India and Japan) represents a national effort to strengthen supply chains in the Indo-Pacific.[xlvi] Analyses by the Productivity Commission and by the Office of Supply Chain Resilience in the Department of Industry, Science and Resources have improved interdepartmental coordination.[xlvii] Home Affairs’s establishment of critical technology supply chain principles further supports these efforts at the policy level.[xlviii] Arguably, however, more needs to be done, particularly by Defence, given Australia’s degree of reliance on platforms, systems and supply classes (including several key natures of ammunition) that are manufactured offshore and would have to be imported across potentially threatened sea lanes in the case of conflict.

Singapore’s Total Defence Model

Singapore has a strong historical focus on homeland defence and resilience, driven by the circumstances of the nation’s founding and its geographical positioning between larger (and not always friendly) neighbours. The TD concept was formally created only in 1984, but it draws on the national service program created in 1967. This, in turn, built upon internal security arrangements established by the Malayan Federation (which included Singapore at the time) during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960). It also reflected lessons learned from Singapore’s experience of occupation by Japan in 1942–1945. The Swiss and Finnish models of TD have been cited as sources for Singapore’s model, the goal of which is to create a civil defence framework and elevate it alongside pre-existing military defence arrangements, forming an overarching national security capability that draws on Singapore’s full resources and gives every Singaporean citizen a part to play.

When first established in 1984, TD comprised five pillars (military, civil, economic, social, and psychological) with a sixth, digital, added in 2019 to reflect increased cyberthreats. Singapore updated its model to include digital defence at around the same time that NATO increased its emphasis on digital resilience within the alliance resilience framework, perhaps reflecting heightened global appreciation of the risk of cyber-attack and malign influence. There have been calls in Singapore’s parliament to add a seventh pillar, climate. While this proposal remains under discussion, the current pillars are described by the Singaporean Government as follows:

- Military defence is having a strong Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) to deter aggression and protect the country. It also involves citizens doing their part to support the military. This involves obligatory national service in the SAF for two years by able-bodied males above 16 years of age, followed by reserve service with obligations to maintain physical fitness and attend annual in-camp training.

- Civil defence provides for the safety and basic needs of the whole community so that life may go on as normally as possible during emergencies. This pillar includes police, fire, ambulance and the Singapore Civil Defence Force, a uniformed organisation under the Singapore Ministry of Home Affairs which provides firefighting, rescue, emergency medical support and civil defence.

- Economic defence is the government, business and industry organising themselves to support the economy at all times. Individuals contribute by working hard and meeting the challenges of development. Those who continually improve themselves to stay relevant play an even bigger role. Economic defence includes stockpiling key commodities including food, water, medical supplies and personal protective equipment, along with efforts to create redundant supply chains and safeguard water supplies.

- Social defence is about people living and working together in harmony and spending time on the interests of the nation and community. Social defence is focused on countering foreign influence, radicalism and extremism, while keeping Singapore’s multicultural and multi-faith society harmonious.

- Digital defence requires every individual to be the first line of defence against threats from the digital domain. Digital defence includes cybersecurity efforts, training of cyber defence teams and regular audits of critical digital infrastructure.

- Psychological Defence is each person’s commitment to and confidence in the nation's future. In addition to focusing on mental health, this component includes countering misinformation and disinformation, and building psychological resilience.[xlix]

The TD framework has been applied in several crises, most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2023 study noted that Singapore’s COVID-19 pandemic experience had shown that TD was ‘a viable framework for facilitating a coordinated, multi-domain response to a non-conventional security threat’ and that the persistence of non-conventional security threats and hybrid warfare indicated that Singapore must continue to adopt a TD approach.[l] The analysis noted that coordination and collaboration, including forging ‘collaborative partnerships (i.e., government-to-government, public-to-private, private-to-private) for crisis management’ must occur pre-crisis and that the ‘immediacy of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity for young Singaporeans to understand total defence as “lived” experience rather than a set of ideals or principles imposed from top-down’.[li]

Singapore’s Total Defence Framework: Implications for Australia

Singapore has much to offer Australian policymakers’ thinking about national resilience and mobilisation. As an open, connected society reliant on global trade and embedded in the international rules-based order, Singapore cannot pull up the drawbridge and attempt to turn itself into a fortress. Indeed, this was a key lesson from 1942, which informed the creation of TD in 1984. The TD framework represents a functional approach to resilience, considered as a set of activities involving various categories of action, rather than (as in the NATO resilience agenda or Australia’s 2021 legislation) a target set to be protected. As an approach that has adapted over decades to a range of threats including military tension, terrorism, financial crises and pandemics, TD has proven its utility and flexibility. It shows the value of a capable, empowered home affairs team that embeds defence (SAF), police, internal security and intelligence representatives in multi-functional teams and coordination centres, developing enduring relationships among personnel within operational departments.

Certain pillars of Singapore’s approach—social and psychological defence, and some elements of economic defence—might prove controversial in Australia if implemented in the same way as in Singapore. Even in Singapore’s close-knit environment, some aspects of social cohesion and psychological mobilisation have been criticised by opposition parties (and challenged in the courts) as authoritarian. This, of course, has also been true of Australian efforts to counter violent extremism, and (particularly at the state level) of pandemic-era mandates, travel bans and lockdowns. In this sense, though Singapore differs from Australia in many ways, the government of Singapore faces similar challenges in preserving human rights and democratic freedoms while building resilience against foreign influence and hybrid threats. As for NATO’s centre for democratic resilience, this inherent tension is likely to be one of the more contested aspects of any future national resilience program.

One other noteworthy aspect of Singapore’s approach, of relevance to Australia’s consideration of national mobilisation, is its use of a large-scale national service scheme including all male Singaporean citizens and second-generation permanent residents. National service has, of course, been a longstanding—and at times politically controversial—aspect of Australia’s national defence preparedness (as discussed below), and Singapore’s experience is a useful point of comparison despite its differences from Australia.[lii] As of 2023, this scheme produced approximately 50,000 national service full-time personnel performing an initial two years of compulsory full-time service. After this initial period, national servicemen perform a further 10 years of part-time service as operationally ready reservists, during which time they are assigned to operational units and required to undertake regular individual and unit training.

As of 2023, the total available reserve personnel pool generated in this manner was approximately 350,000 part-time personnel, on top of the 50,000 performing full-time service. All Singaporean male citizens and second-generation permanent residents are required to register for national service at the age of 16 years and six months, and then undergo psychological, aptitude, medical and other testing to determine suitability for different forms of service. Service can be undertaken in the SAF, Singapore Police Force, or Singapore Civil Defence Force (a uniformed service under the Ministry of Home Affairs, which provides emergency services including firefighting, rescue, and emergency medical response, and coordinates the national civil defence scheme under the TD construct).

Baltic States (‘Small-State Resilience’ and ‘Total Defence’)

The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) each have distinctive approaches to resilience and mobilisation. However, the similarities among these nations’ approaches outweigh their differences, reflecting shared geography—living next door to an aggressive great power—and a common history of imperial Russian and Soviet occupation, followed by hybrid warfare directed at them by the post-1991 Russian Federation.

The Baltic model:

includes not just the national armed forces and allied forces, but also the mobilisation of all national resources towards defeating an invader, along with active resistance by every citizen that is in any way legitimate under international law.[liii]

Civilians under hostile occupation are prepared to engage in both non-violent and armed resistance under a legal framework, controlled, directed and supported by the national government (whether inside the country or operating externally as a government-in-exile), with the objectives of:

imposing direct or indirect costs on an occupying force, securing external support, denying an occupier’s political and economic consolidation, reducing an occupier’s capacity for repression, and maintaining and expanding popular support [for the legitimate government].[liv]

Current capabilities reflect recent hybrid, political, economic and cyberwarfare attacks from Russia, and heightened mobilisation posture since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Each country considers military defence as ‘closely intertwined with nonmilitary or civilian capabilities and policies, with a special role for the citizenry and the national consciousness’ and has adopted a whole-of-society approach that is ‘now considered an integral part of national defence and encompasses not only active and passive resistance but also early warning and protection of the population’.[lv] Governments in the Baltic states are ‘educating their societies about national defence and creating familiarity and links with military service branches via reintroduction or expansion of mandatory service and strengthening of national voluntary forces’.[lvi] Components of this approach include:

- Military defence capabilities

- Civilian support for military defence

- Public-private cooperation for defence

- Psychological defence

- Civil protection and civil defence

- Strategic communications

- Domestic and internal security

- Continuous operation of the state and country

- Cybersecurity

- Economic resilience.[lvii]

Sometimes described as ‘deterrence through resilience’, this approach recognises that as small nations (in terms of both territory and population), Baltic countries are unlikely to defeat a direct invasion. However, a resilient posture demonstrating the costs any invader would suffer may change an adversary’s calculus. Cost-imposition strategies can be structured across multiple categories, including time (slowing an invader), space (forcing an attacker to secure multiple locations or extended supply lines) and materiel (requiring an attacker to consume resources beyond the value of the objective sought).[lviii] The goal is to demonstrate, ahead of conflict, that the cost of invasion would outweigh any benefit, and thus deter adversary action. Recently a fourth category—reputational cost—has been raised by the damage Russian forces initially suffered in Ukraine to their reputation for competence and effectiveness. The aim of cost imposition is to defeat an adversary’s ‘will to engage in—or continue with—aggression by denying benefits, increasing costs and influencing their perception of both costs and benefits’ while at the same time the ability to resist an invasion would ‘send an important political message to Allied governments, namely that the local population does not accept the new rulers and is putting their lives on the line to defend their national sovereignty’.[lix]

Beyond these similarities, Baltic states differ from each other in their planning and policy settings, approaches to conscription, and civilian resistance frameworks. Estonia, having suffered cyber and physical attacks, emphasises territorial and cyber sovereignty, supported by ‘participation of all sectors of society, including government institutions, the private sector and civil organizations’.[lx] Estonia has maintained conscription since its independence in 1991. Besides the regular military, the Estonian Defence League, an armed volunteer organisation supported by Estonia’s department of defence, has approximately 17,000 members and another 11,000 volunteers within its women’s and youth leagues.[lxi] It works with Estonian special operations forces and conventional forces to conduct territorial defence and guerrilla resistance in time of war, and performs civil defence and emergency response functions in peacetime.

Latvia currently maintains an all-volunteer military, and focuses on improving its ability to:

resist hybrid threats that may be economic, political and technological in nature, to counter information warfare and, like Estonia, to increase social cohesion. As outlined in the 2016 State Defence Concept, civil-military cooperation is part of the national security approach and brings together state administrative institutions, the general public and the national armed forces. According to the Latvian Constitution, the ability of the population to engage in individual and collective resistance is regarded as an indivisible part of the national identity and civic confidence, forming the foundation of state defence against any aggressor.[lxii]

Lithuania reintroduced conscription in 2016. Its approach includes mobilising all national resources to defeat an invader, along with guerrilla resistance by all citizens, as noted above. Lithuanian strategic documents include the concept of civil resistance, defined to include all citizens of Lithuania, either acting as individuals or formed into small units, and engaging in a range of activities, both armed and unarmed, against aggression and occupation.[lxiii] Lithuania has also:

used the concept of ‘comprehensive security’ which stands for the cooperation of military and civilian institutions and interoperability of military and civilian capabilities … The Ministry of National Defence has supported this effort by publishing extensive practical recommendations on how to prepare for and act in emergencies and war, issuing a brochure with focus on resilience in 2015, and issuing a third volume focusing on resistance in 2016.[lxiv]

In its 2020 threat assessment, Lithuania’s intelligence service laid out a useful categorisation of issues relevant to national resilience. These included regional security, military security, activities of hostile intelligence and security services, protection of constitutional order, information security, economic and energy security, terrorism and migration, and global security.[lxv]

In 2019, working with the Swedish Defence University, the US theatre special operations component in Europe (SOCEUR) developed a Resistance Operating Concept (ROC) building on Baltic and Nordic experiences and lessons learned from Second World War and Soviet-era resistance movements, armed and unarmed.[lxvi] The ROC is complemented, within US organisations, by a Resistance Manual for personnel engaged in support to resistance, and within participating countries by civil and (in some cases) armed resistance handbooks.[lxvii] In early 2020, SOCEUR and its partner nations co-sponsored a symposium alongside Special Operations Component Pacific (SOCPAC), enabling Taiwan, South Korea and other Indo-Pacific countries to compare notes on total defence, contributing to Taiwan’s ODC. The ROC is likely to be updated in the near future, to reflect lessons learned by regional countries as a result of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Baltic Total Defence: Implications for Australia

The Baltic countries differ from Australia in that direct military invasion of national territory by a neighbouring country is the primary threat towards which their mobilisation and resilience systems are oriented. As a result, and because of the size mismatch with Russia, territorial defence (including armed resistance against an occupier) is a key component of the Baltic model. Australia has lower risk of direct territorial invasion, hence less need for Baltic-style asymmetric territorial defence. At the same time, Australia’s offshore infrastructure, extended trade networks and reliance on international telecommunications and supply chains make it possible for an adversary to dislocate Australian society without an invasion. Therefore, the Baltic focus on cyber defence, rapid national mobilisation, whole-of-nation partnerships and use of emergency services and civil defence leagues to bolster capability in the event of war are all relevant to Australia.

More importantly, deterrence through resilience and changing an adversary’s calculus through cost imposition are highly relevant for Australia, given that a physical invasion of Australia’s territory is both relatively unlikely, and not necessarily the most dangerous course of action an adversary could adopt.[lxviii] As a result, affecting an adversary’s decision-making before the outbreak of any conflict—and thereby influencing the adversary’s choice of methods and targets—is particularly important for Australia, as is the focus (likewise critical for the Baltic states) on preserving sovereignty amid great power conflict in a wider region. Lithuania’s threat assessment categories (regional security, military security, activities of hostile intelligence and security services, protection of constitutional order, information security, economic and energy security, terrorism and migration, and global security) are a useful framework through which to consider Australia’s national mobilisation needs.

Taiwan’s Overall Defence Concept

The Republic of China (Taiwan) introduced its ODC in 2020, following debate within the Taiwanese Government and military-to-military engagement with like-minded countries. The ODC is Taiwan’s concept to deter and, if necessary, defeat attack by Communist China. As an integrated strategy, the ODC emphasises Taiwan’s constrained resources, ‘existing [geographical] advantages, civilian infrastructure and asymmetric warfare capabilities’.[lxix] The concept noted that China’s defence budget at that time outweighed Taiwan’s by a factor of 22, while its active forces outnumbered Taiwan’s twelvefold. Recognising that this asymmetry would only grow in the future, the ODC sought to shift away from Taiwan’s traditional focus on small numbers of expensive, high-end conventional weapon systems, towards a larger number of smaller, stealthier, cheaper, more easily dispersed and thus more survivable capabilities.

In support of this reorientation, the ODC emphasises national resilience ahead of and during conflict, whole-of-nation support to the armed forces, homeland defence, deterrence through resilience, and civil resistance. It also offers a mobilisation construct, with one of its two components—‘force buildup’—focused on developing a survivable force that can endure missile, air and cyber attacks ahead of (or instead of) an invasion. Civilian infrastructure is repurposed for dual use or military application, and a whole-of-nation civil resistance structure supports Taiwan’s military reserve forces, who would act as an asymmetric territorial defence force.[lxx]

China’s response to a visit to Taipei by US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi in August 2022 involved the unprecedented launching of missiles directly over Taiwan, and triggered ‘a visible swelling of public concern about the possibility of war erupting across the Taiwan Strait’. Such factors have resulted in ‘a marked increase in the Taiwanese public’s interest in civil defense preparedness’ and a recognition of national mobilisation and resilience as a key component of deterrence and a way to shape an adversary’s calculus ahead of conflict.[lxxi]

National resilience and mobilisation programs that support the ODC’s military elements include civil defence programs, along with several ‘bottom-up’ approaches started—on a voluntary basis but with government support—by civil society groups. One such program is the Kuma Academy, a volunteer organisation funded by donations from the public and wealthy individuals, which conducts one-day courses for civilians across a range of civil defence and emergency response skills. The academy’s courses are taught by professional instructors, and also cover resistance warfare skills and ‘topics like cognitive warfare methods, modern warfare, and basic rescue and evacuation practice’.[lxxii] Another is the Forward Alliance, founded by a Democratic Progressive Party politician who is also a military veteran, which provides training courses for groups of 400 to 500 civilians per month, focusing on civil defence and disaster relief.[lxxiii]

In Taiwan the legal authority for civil defence was formalised in January 2021 with the passage of the Civil Defence Act, which gave the Ministry of Interior (MOI) authority over civil defence in peacetime and tasked the MOI to raise a civil defence force that would transfer to Ministry of Defense control in wartime. The law details the legal scope of civil defence, appoints management authorities to coordinate defence at the central level and down to the village level, and specifies the organisation of civil defence forces.[lxxiv] Within the MOI, the National Police Agency (NPA) runs a civil defence command and control office. As a recent study notes:

there is no official data on the number of civilians currently involved in the NPA’s civilian defence force, and details about their training and proficiency are sparse. In turn, this lack of information has allowed for little public accountability around what the law mandates. Recent anecdotal evidence claims that the NPA’s civil defence force has around 50,000 civilians, mostly comprised of men between the ages of 50 and 70, who perform four hours of training per year.[lxxv]

The initially lacklustre performance of the civil defence force may have contributed to a groundswell of bottom-up national resilience activities in Taiwan, particularly noticeable since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[lxxvi]

Taiwan’s Overall Defence Concept: Implications for Australia

As a like-minded democracy in the Indo-Pacific region, under both hybrid and conventional threat from an aggressive China, Taiwan’s approach has much to offer for Australian policymakers. The creation of a single central authority under a home affairs ministry, with the establishment of a single national C2 centre within the National Police Agency, offers lessons for how to structure a civil defence and mobilisation capability, while also offering cautionary indications of what can happen when a motivated population perceives that limited steps are being taken by the government and takes matters into its own hands. Taiwan’s ODC concept draws directly from NATO’s resilience agenda and from the SOCEUR/SOCPAC workshop series that shared with Taiwan several key lessons from the Baltic and Nordic states’ approach to resilience and asymmetric defence.

Taiwan differs from Australia in significant ways. Most notably, it is far smaller in land area than Australia (though similar in population, at 24 million people compared to Australia’s 26 million). Taiwan is threatened by invasion from mainland China, as well as blockade and rocket or missile strikes, along with hybrid political, economic, cyber and information warfare attacks. Thus, as for the Baltic states, direct territorial invasion looms larger for Taiwanese analysts than for Australian ones. At the same time, like Australia, Taiwan is a democracy whose survival is tied to the free global flow of commerce and commodities under a stable international rules-based order. A ‘fortress Taiwan’ would not be sustainable over the long term, even though (unlike Singapore) Taiwan does have a forested, mountainous hinterland that might sustain guerrilla-based resistance warfare for an indefinite period under occupation. Thus, for Australians, Taiwan’s mobilisation approach offers insights on how to regulate, structure and operate a national resilience system in a democracy being subjected to hybrid warfare and foreign interference.

Endnotes

[xxxiv] See Wolf-Diether Roepke and Hasit Thankey, ‘Resilience: The First Line of Defence’, NATO Review, 27 February 2019, at: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2019/02/27/resilience-the-first-line-of-defence/index.html.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, ‘Centres of Excellence’, NATO website, updated 6 December 2022, at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_68372.htm.

[xxxvii] For a full list of COEs see North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Command Transformation, NATO-accredited Centres of Excellence, 2022 Catalogue, at: https://www.act.nato.int/application/files/6716/3911/5570/2022-coe-catalogue.pdf.

[xxxviii] See Hybrid Centre of Excellence, at: https://www.hybridcoe.fi.

[xxxix] Roepke and Thankey, ‘Resilience’.

[xl] Edward Lundquist, ‘NATO Learns Lessons from COVID-19 Crisis’, National Defense, 30 August 2021, at: https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2021/8/30/nato-learns-lessons-from-covid-19-crisis.

[xli] See Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørv, ‘Coronavirus, Invisible Threats and Preparing for Resilience’, NATO Review, 20 May 2020, at: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2020/05/20/coronavirus-invisible-threats-and-preparing-for-resilience/index.html.

[xlii] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Strengthened Resilience Commitment, 14 June 2021, at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_185340.htm?selectedLocale=en.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] See NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Recommitting to NATO’s Democratic Foundation: The Case for a Democratic Resilience Centre within NATO Headquarters, at: https://nato-pa.foleon.com/coordination-centre-on-democracy-resilience/the-case-for-a-centre-for-democratic-resilience-in-nato/.

[xlv] See ‘Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Bill 2021’, Parliament of Australia website, at: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r6657.

[xlvi] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), ‘Joint Statement on the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative by Australian, Indian and Japanese Trade Ministers’, DFAT website, 27 April 2021, at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/news/media-release/joint-statement-supply-chain-resilience-initiative-australian-indian-and-japanese-trade-ministers; and ‘Joint Statement on the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative by Australian, Indian and Japanese Trade Ministers’, DFAT website, 15 March 2022, at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/news/media-release/joint-statement-supply-chain-resilience-initiative-australian-indian-and-japanese-trade-ministers-0.

[xlvii] See Productivity Commission, Vulnerable Supply Chains: Study Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021), at: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/supply-chains/report; and Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR), ‘Office of Supply Chain Resilience’, DISR website, at: https://www.industry.gov.au/trade/office-supply-chain-resilience.

[xlviii] Department of Home Affairs, Critical Technology Supply Chain Principles (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021), at: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/cyber-security-subsite/files/critical-technology-supply-chain-principles.pdf.

[xlix] Government of Singapore, Ministry of Defence (MINDEF), ‘What Is Total Defence?’, MINDEF website, at: https://www.mindef.gov.sg/defence-matters/defence-topic/total-defence.

[l] Sarah Soh, Total Defence in Action—Singapore’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, RSIS Commentary No. 022 (Singapore: S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 2023), at: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/nssp/total-defence-in-action-singapores-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/#.ZBIvai-r19c.

[li] Ibid.

[lii] For an overview of conscription policy and related controversies in Australia see Australian War Memorial (AWM), ‘Conscription’, AWM website, at: https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/conscription.

[liii] Michael Peck, ‘Total Defense: This Is the Baltic’s Best Bet to Stop a Russian Invasion’, The National Interest, 9 November 2020, at: https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/total-defense-baltic’s-best-bet-stop-russian-invasion-172267.

[liv] Anika Binnendijk and Marta Kepe, Civilian-Based Resistance in the Baltic States: Historical Precedents and Current Capabilities (Washington DC: RAND Corporation, 2021), Ch. 2.

[lv] Ibid., p. 78.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] See Doowan Lee, Cost Imposition: The Key to Making Great Power Competition an Actionable Strategy (West Point: Modern Warfare Institute, 2021), at: https://mwi.usma.edu/cost-imposition-the-key-to-making-great-power-competition-an-actionable-strategy/.

[lix] Marta Kepe and Jan Osburg, ‘Total Defense: How the Baltic States Are Integrating Citizenry into Their National Security Strategies’, Small Wars Journal, 24 September 2017, at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/total-defense-how-the-baltic-states-are-integrating-citizenry-into-their-national-security-.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Government of Estonia, Estonian Defence League, at: https://www.kaitseliit.ee/en/edl.

[lxii] Kepe and Osburg, ‘Total Defence’.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Second Investigation Department under the Ministry of National Defence and State Security Department of Republic of Lithuania, National Threat Assessment 2020 (Vilnius: Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2020) at: https://www.vsd.lt/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2020-Gresmes-En.pdf.

[lxvi] Otto C Fiala, Resistance Operating Concept (ROC) (MacDill Air Force Base, FL: The JSOU Press, 2020), at: https://jsou.edu/Press/PublicationDashboard/25.

[lxvii] U.S. Army Special Operations Command, Resistance Manual (DRAFT) (Fort Bragg, NC: USASOC, 2019), at: https://www.soc.mil/ARIS/books/pdf/resistance-manual.pdf.

[lxviii] For a discussion of these points see Hugh White, How to Defend Australia (Melbourne: Latrobe University Press, 2019); and the author’s comments on White’s argument as contained in David Kilcullen, ‘Book Review: Hugh White, How to Defend Australia’, Australian Foreign Affairs 7 (October 2019), at: https://www.australianforeignaffairs.com/articles/review/2019/11/how-to-defend-australia/david-kilcullen.

[lxix] Lee Hsi-min and Eric Lee, ‘Taiwan’s Overall Defense Concept, Explained: The Concept’s Developer Explains the Asymmetric Approach to Taiwan’s Defense’, The Diplomat, 3 November 2020, at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/taiwans-overall-defense-concept-explained/.

[lxx] Ibid.

[lxxi] Russell Hsiao, ‘Taiwan’s Bottom-up Approach to Civil Defense Preparedness’, Global Taiwan Brief 7, no. 19 (2022), at: https://globaltaiwan.org/2022/09/taiwans-bottom-up-approach-to-civil-defense-preparedness/.

[lxxii] Ibid.

[lxxiii] Helen Davidson, ‘Second Line of Defence: Taiwan’s Civilians Train to Resist Invasion’, The Guardian, 22 September 2021, at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/22/second-line-of-defence-taiwans-civilians-train-to-resist-invasion.

[lxxiv] Ibid.

[lxxv] Ibid.

[lxxvi] Author’s discussion with personnel from the Republic of China Armed Forces (ROCAF) and civil society resilience organisations, Taipei, 20 January 2024. See also Natalie Tso, ‘Taiwan’s Civilian Soldiers, Watching Ukraine, Worry They Aren’t Prepared to Defend Their Island’, Time, 18 March 2022, at: https://time.com/6158550/taiwan-military-china-ukraine/.

Insights from the Comparative Analysis

Australia’s circumstances differ in detail from each of the four comparative examples analysed. However, relevant insights for Australian resilience include the following:

- Establishing a stated set of resilience priorities—centrally updated, furthered by a coordinating body and advanced through a network of capacity-building centres—helps focus resilience efforts and allows states and territories to align with national priorities and draw on national resources.

- Supply chain resilience was an under-emphasised area before the pandemic. NATO may update its framework to include supply chain resilience as an additional requirement. In Australia’s case, the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative and the Office of Supply Chain Resilience may help strengthen supply chains, as will Home Affairs’s critical technology supply chain principles. However, this is a dynamic area that requires continuous monitoring and updating in order to keep abreast of changing circumstances. Arguably, a concentrated effort to integrate and align supply chain resilience efforts across Commonwealth agencies and between the Commonwealth and the states and territories should also be a high priority for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Singapore’s TD framework is a functional approach to resilience, defined in this context as a set of activities involving various categories of action, rather than as a target set to be protected. In updating the categories of national security noted in Strong and Secure, Australian planners may wish to draw on Singapore, Taiwan, the Baltic states and NATO for updated functional frameworks.

- A total defence concept shows the value of a capable homeland security organisation that embeds defence force, police, internal security and intelligence community personnel in multi-functional teams and coordination centres, developing relationships among personnel within operational departments.

- Preserving human rights and democratic freedoms while building resilience against foreign influence is critical, but problematic for multiple countries and for NATO. Countering disinformation and foreign influence is likely to be one of the more contested aspects of any future national resilience program.

- The Baltic states’ focus areas of cyber defence, national mobilisation, whole-of-nation partnerships and use of emergency services and civil defence leagues to bolster capability in the event of war are all relevant to Australia.

- Deterrence through resilience and use of cost-imposition strategies to change an adversary’s calculus are highly relevant concepts for Australia, as is the Baltic states’ focus on preserving sovereignty amid great power conflict in the region.

- Taiwan’s creation of a single central authority under their home affairs agency, with a national command and control centre in the national police headquarters, offers lessons on structuring civil defence. The Taiwanese Civil Defence Act of 2021 is worth studying as a model for coordination of national resilience.

- Similar to the Baltic states, direct invasion looms larger for Taiwan than for Australia. At the same time, like Australia’s and Singapore’s, Taiwan’s survival is tied to the free global flow of commerce and commodities under a stable international rules-based order. Taiwan’s approach offers insight on national resilience in a democracy subjected to hybrid warfare and foreign interference.