Introduction

Project Land 400 Phase 3 aims to introduce into service an infantry fighting vehicle (IFV). This will replace Army’s aged armoured personnel carrier (APC) capability, which has been in service since 1965. The IFV acquisition provides Army’s infantry with enhanced firepower, mobility and protection to enable them to fight, win and survive close combat in the contemporary threat environment. However, discourse on the acquisition has often suffered from a poor and incomplete understanding of the differences between IFVs, APCs and other armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs). Equally, it is evident that the differences between the different types of infantry forces which operate AFVs and the approaches which guide their employment are also not well understood. Therefore, to inform discussion on this important project, it is necessary to examine the development of the IFV as well as the types of infantry forces which operate IFVs.

This article provides a short history of the development of armoured vehicle-borne infantry over the course of the 20th century, encompassing motorised, mechanised and armoured infantry types. Complementing this analysis, it examines the vehicle technologies which were developed to equip these forces over this period. It also explores the different philosophies which underpin these infantry force types in the 21st century and it concludes by considering which approach may best suit Army as it introduces the IFV into service.

Infantry Mobility and Firepower

Throughout history efforts have been undertaken to enhance the mobility of the traditionally foot-borne infantry arm. These included mounting infantry on horses, mules, camels and wagons. This approach was driven by the need to deploy infantry faster and further as well as to lessen the effects of fatigue on the infantry. The late 16th century Dragoons are an early modern example. They rode to battle on horseback, dismounted in a secure area where the horses were held, and then fought on foot. While dragoons were more mobile than other infantry, they did not fight mounted or perform scouting or security tasks, these being the purview of the cavalry.[1] One of the last examples of horse-mounted infantry prior to the widespread adoption of the combustion engine in the early 20th century was the British Army’s Mounted Infantry. These were infantry temporarily provided enhanced mobility to travel to the battlefield, who then dismounted to employ firepower. Unlike British irregular Mounted Rifles or regular Cavalry, Mounted Infantry were neither trained nor equipped to fight mounted. The zenith of Mounted Infantry in the British Army was the Second Boer War, where their mobility afforded them a distinct advantage over foot infantry.[2]

Prior to this the maturation of the steam engine in the mid-1800s provided the means to deploy large bodies of troops and materiel. Where rail and stations existed, this provided the ability to transport infantry quickly over long distances to a theatre of war greatly improving their strategic mobility and reducing march distances to the front.[3] It was during the First World War that motorised wheeled vehicles powered by the internal combustion engine, such as cars, trucks and buses, were first employed to move infantry in significant numbers. Motorised transport supplemented the use of railways by moving infantry from stations closer to the front, further reducing distances travelled on foot. However, motorised transport did not improve their mobility on the battlefield, with the infantry forced to fight across fire-swept ground on foot.

Infantry firepower also evolved during the war. Rapid-fire and high-explosive weapons gradually devolved from brigade and battalion levels and were integrated into platoons and sections. Machine guns, automatic rifles, mortars and grenades enabled infantry sections to employ the basic tactic of one element providing a static fire support to prevent an enemy from moving and firing, while another mobile element moved to close with them. This provided the ability to defeat entrenched defenders through the combination of suppressing fires and high-explosive destructive firepower.[4] By the war’s end, infantry tactics incorporating fire and movement at the section level had eclipsed the massed infantry linear tactics which the war had begun with. Importantly, the application of fire and movement—the most elementary form of manoeuvre—remains fundamental to minor tactics today and underpins the integration of infantry and armoured vehicles.

After years of relatively static attritional trench fighting, particularly on the Western Front, the last months of the war saw the resumption of mobile warfare. Notably, the Battle of Amiens (1918) demonstrated the potential of tracked mechanised forces, such as tanks, to increase the tempo of battle.[5] Tanks provided the infantry a means to quickly breach tactical obstacles such as wire and provided supressing fire support to cover their movement as well as destroying enemy strong points. Tanks also conserved the infantry force by physically protecting them. The tank was also developed into an artillery gun carrier, specialised engineer variants and supply transports,[6] serving as a portent of the potential of mechanisation. However, at the end of the war exactly how mobility and firepower could be combined to best enhance the infantry arm remained unclear.

Motorised Infantry

Following the war technological advances resulted in tank-equipped forces (collectively termed armour) becoming better protected, more reliable and faster. The latter drove the need for the infantry, and other arms and services, to become more mobile to keep pace and reap the benefits of operating together. An initial step undertaken was the permanent provision of unprotected trucks and utility vehicles to mobilise the infantry, creating a new type of force—Motorised Infantry. Conceptually similar to horse-borne mounted infantry, motorised infantry moved mounted, but dismounted in a safe area to then close with the enemy and fight on foot.[7] Trucks could transport large sections of infantry with additional ammunition, stores and equipment. Thus, the chief benefits of this type of force were significant improvements to the infantry’s operational mobility (the speed and range at which they could be deployed) and their endurance, given their immediate access to supplies and a lessening in fatigue from the reduction in distances marched on foot. However, while infantry could move further and faster once motorised, they were primarily road-bound whilst mounted. Consequently, their ability to move with armour off-road remained limited.

During the Second World War motorisation and mechanisation of Western militaries accelerated greatly. The war demonstrated that the cooperative combined-arms use of infantry and armour was essential during close combat, negating previous views that either could or should operate alone. Infantry-armour tactics were mutually supporting; one element provided intimate protection and the other intimate support in return. However, in order to achieve such mutual support during mobile operations, the infantry required mobility commensurate with that of armour. Early combat experience illustrated the limitations of motorised infantry, such as British Motor Battalions and German Schützen (Rifle) units. Both forces possessed limited off-road tactical mobility (typified by speed, turn, gap crossing and climbing abilities) and were vulnerable to small-arms and artillery fire. This negated their ability to move and fight at the tempo of mechanised, generally tracked, armoured forces. Conversely, when armour was slowed to the pace of dismounted infantry it became increasingly vulnerable to anti-armour weapons. To overcome this, the infantry required a vehicle which had greater off-road mobility and improved protection.[8]

Combatants on both sides turned to open-topped, lightly armed and armoured transports. Examples such as the half-tracked German Sonderkraftfahrzeug (Sd.Kfz.) 251 and the US M3 personnel carrier, as well as the full-tracked British Universal Carrier, provided considerable advances in off-road mobility and some protection from small-arms fire and shell fragments. German Panzergrenadier and US Armored Infantry units thus equipped were able to operate more closely with armour before dismounting to fight on foot. Furthermore, Panzergrenadiers displayed a preference to remain mounted for as long as possible, and even to fight mounted in order to maintain the tempo of operations.[9] However, the limited protection and the mobility differential between half- and full-tracked vehicles remained a barrier to infantry-armour cooperation. Consequently, late in the war Allied armies began to ‘mount’ infantry in armoured personnel carriers (APCs) temporarily. These early APCs, nicknamed ‘Kangaroos’, were expedients created by repurposing obsolete self-propelled artillery and tanks to carry an infantry section. These vehicles were grouped into specially created APC regiments operated by the Canadian and British armoured corps. Wartime experience demonstrated the value of APCs, as they enabled much closer cooperation with armour, as the infantry could move cross-country at the same speed and dismount closer to tanks. Furthermore, the enhanced protection of the APC greatly reduced infantry casualties. While the level of vehicle integration within the infantry was minimal under these arrangements, the potential of equipping infantry with their own AFVs was evident.[10]

Mechanised Infantry

In the 1950s both the US and Britain experimented with this ‘mounted infantry’ model, creating APC organisations to transport infantry. However, these proved to be short-lived as the benefits of infantry with organic mobility proved superior. By the early 1960s both armies had created Mechanised Infantry forces. Akin to motorised infantry, mechanised infantry were permanently provided with vehicles to transport them to battle. Doctrinally, mechanised infantry moved mounted in their APCs, dismounted once contact was made, or outside effective anti-armour fire in an assault, to then move and fight on foot alongside tanks. The APCs, with relatively light armour and limited armament, did not fight alongside the infantry and tanks, instead providing supporting fire from a distance or withdrawing out of contact until required to move the infantry again.[11] Consequently, mechanised infantry forces contained relatively large sections of 10–12 soldiers to provide the maximum amount of dismounted supressing fire to enable fire and movement in close combat. This philosophy was important as it underpinned the design of APCs.

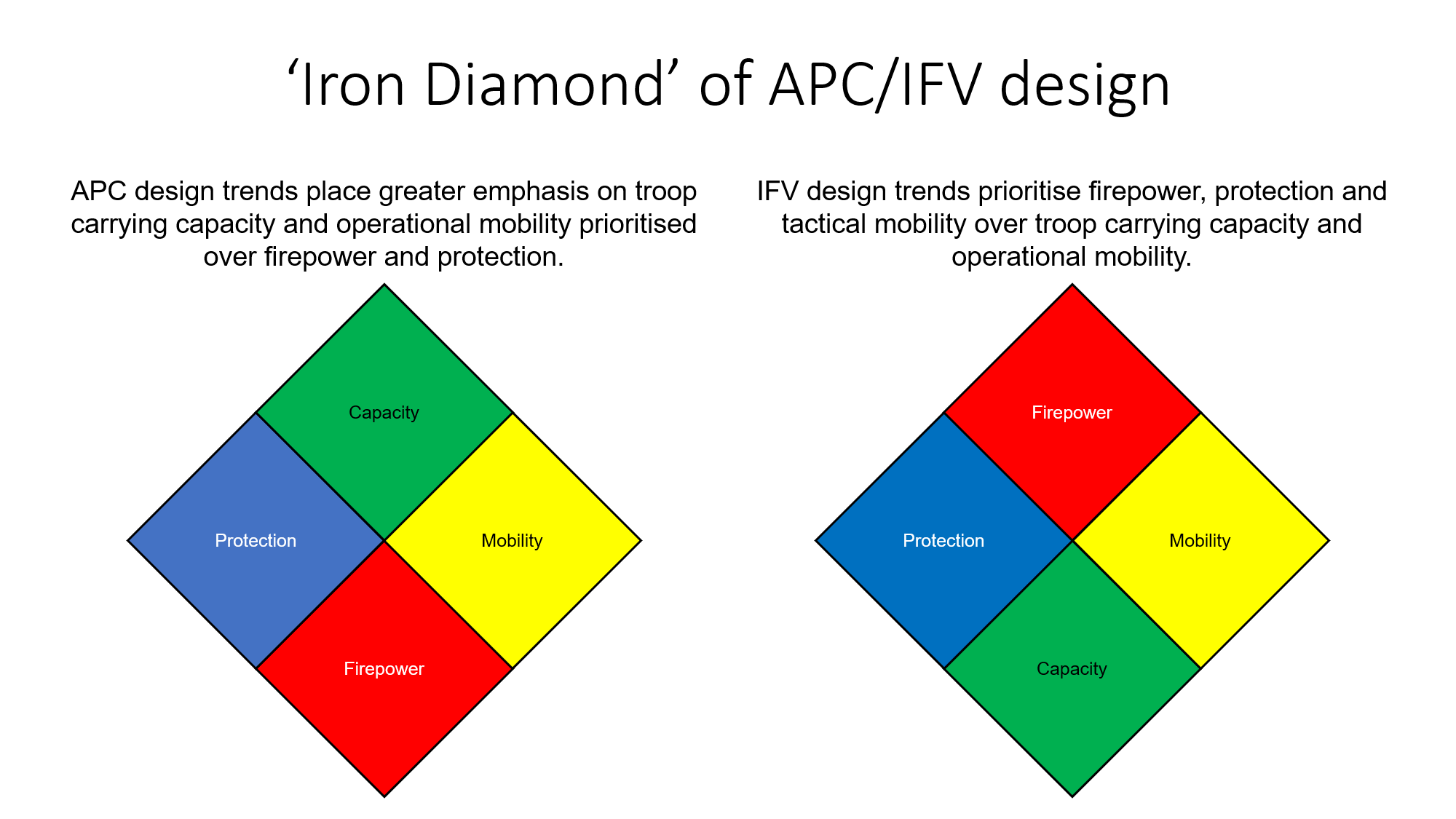

From the mid-1940s numerous wheeled and tracked APC designs were developed to varying levels of success. These included the US M39, M75, M59 and M113, the British FV 432, the French AMX-VCI, the Austrian Saurer 4K and the Soviet BTR-50 and BTR-60 APCs. These were designed as transport vehicles, ‘battle taxis’ to deliver the infantry to the edge of battle to then fight on foot; not to deliver them into close combat or to fight mounted. The emphasis on delivering a large infantry section required considerable internal volume to accommodate them. The desire for improved mobility also encouraged designs that were amphibious and air portable. Consequently, the combination of these design factors required compromises in APC firepower and protection.[12] The weapons fitted were generally adequate for self-defence only and had limited utility in covering friendly vehicle movement or fighting other AFVs. Protection was limited to shell fragments and small-arms fire, leaving these vehicles vulnerable to heavy machine guns, mines and basic shaped charge anti-armour weapons. Furthermore, the infantry had limited, if any, ability to fight or observe from under armour, relegating them to the status of passengers.[13] This meant that infantry troops needed only a basic familiarity and generalist skill base to ride in APCs, dismount and fight on foot. Based on this thinking, the capacity to transport a section of infantry became the key design requirement. This upset the traditional AFV design theory paradigm, often termed the ‘Iron Triangle’ of firepower, protection and mobility, with troop-carrying capacity added to these criteria as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Iron Diamond of APC/IFV design[14]

Armoured Infantry

The combat experiences of Germany, the Soviet Union and the US led to a desire to improve the ability of infantry to fight mounted. This was compounded by the prospect of fighting over ground potentially contaminated by chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons. Given its experience of the Second World War, the German Bundeswehr re-established its Panzergrenadier arm in 1956. The Panzergrenadier (PzGren), literally Armoured Infantry, operated differently to US and British mechanised infantry doctrines. The PzGren approach required infantry with specialised training and equipment to move and fight in as close cooperation as possible with tanks during mounted and dismounted action, in offence and defence.[15] In practice this meant moving mounted alongside tanks, fighting mounted from the vehicles through hatches and firing ports, and fighting dismounted alongside tanks and their own vehicles. While traditional infantry tasks were maintained, PzGren methods concentrated less on positional or terrain-focused approaches and more on mobile methods and anti-armour tasks. Also reflective of wartime experience, the PzGren could be employed as an independent entity, offering a medium-weight alternative to heavier armoured or lighter infantry forces.[16]

To implement this doctrine the PzGren required a vehicle tailored to this role with capabilities beyond those of an APC. The first attempt was the Schützenpanzer 12-3 (SPz), designed in the late 1950s. Arguably the ‘proto’ IFV, the SPz incorporated capabilities which evolved it into a vehicle that infantry could fight with, rather than simply a transport in which they were passengers.[17] It was relatively heavily armoured and fielded a 20 mm auto-cannon to support its infantry and fight other AFVs. However, it only carried five infantry, who could fight from open hatches but not from under armour. The SPz and contemporaries such as the Swedish Pansarbandvagn 301, French AMX-VCI and US XM734 represented transitional designs incorporating aspects of both APCs and IFVs. These designs were superseded by the Soviet BMP-1 in 1966. Arguably the first ‘true’ IFV, the BMP-1 embodied much of the contemporary thinking on armoured vehicle-borne infantry and represented a significant evolution in infantry firepower, protection and mobility. The BMP-1 provided Soviet infantry with increased mobility to accompany tanks and delivered heavy direct fire support from a low-pressure cannon, an anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) and numerous machine guns. It was protected from small-arms fire and from artillery fragmentation, and featured radiation shielding. It carried a smaller section of eight infantry with a crew of three. Notably the infantry could fight from within the vehicle or dismount and fight on foot. For the Soviets this provided a vehicle which enabled their infantry to move in concert with tanks, across potentially contaminated ground, and could contribute to combat rather than simply deliver infantry to the fight.[18]

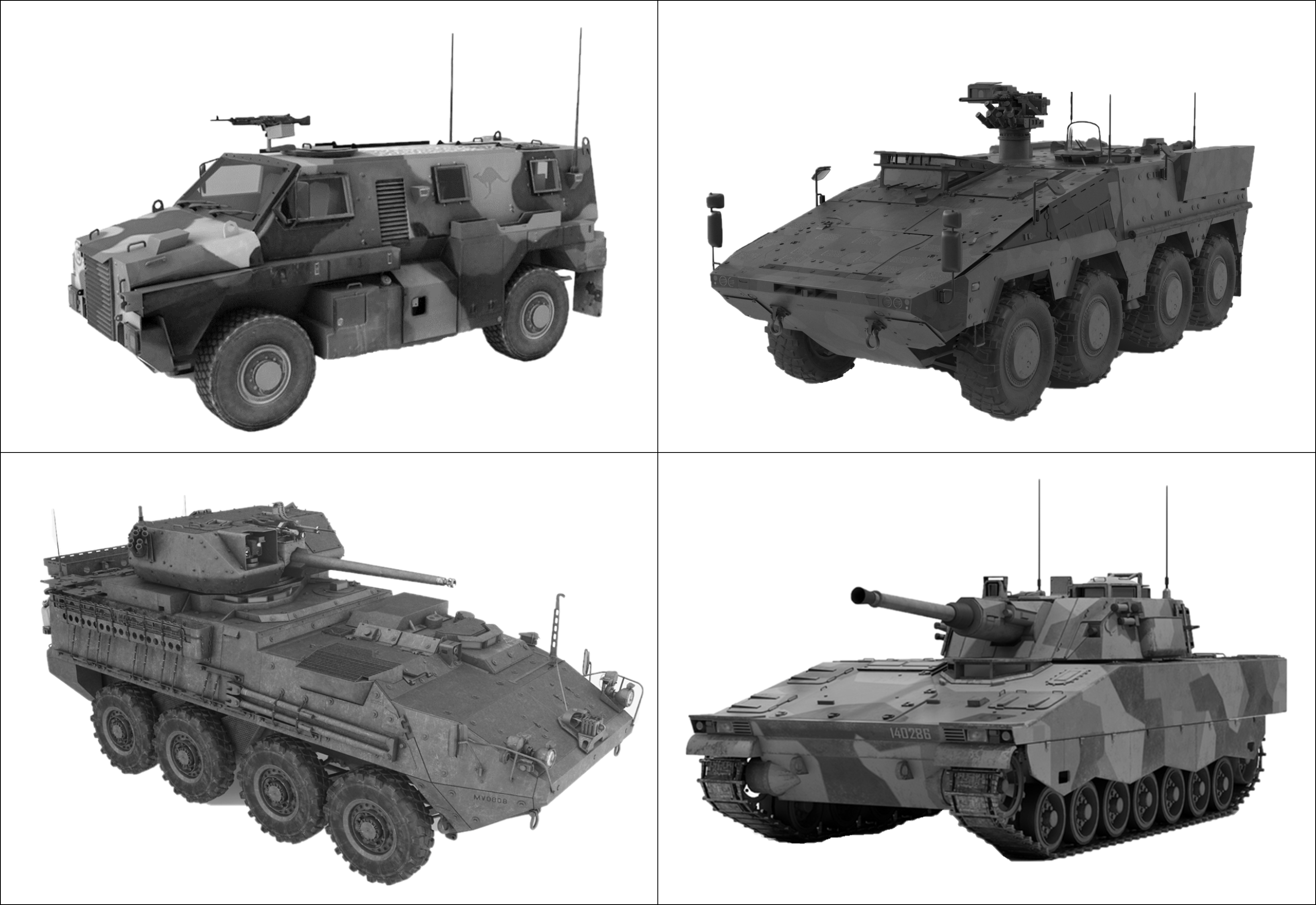

Subsequent IFV designs, such as the German Marder, French AMX-10, Dutch YPR765 and Soviet BMD, reflected the ascendance of firepower and protection over mobility and capacity in design. IFV armaments typically included auto-cannon with calibres of 20mm or larger, ATGM, machine guns and grenade launchers. These provided the ability to sustain high rates of fire to supress or neutralise infantry behind cover, protect vehicles when moving tactically and destroy other AFVs. The ability of infantry to observe and fight under armour was enhanced by the use of episcopes/periscopes, electro-optics and hatches, as well as the adoption of firing ports in the sides of the vehicles. Likewise, protection increased with frontal arc armour designed to defeat auto-cannon projectiles, complemented by all-round defence against heavy machine gun and shell fragments. Furthermore, the CBRN threat resulted in the incorporation of air filtration/overpressure systems, increased shielding and development of specialised protective clothing and techniques. To cope with design changes, larger, more powerful engines and improved suspension were needed to ensure IFVs could accompany tanks across country. However, the cost of this was often capacity, leading to a reduction in the size of the sections that could be carried.[19] Thus, while infantry gained advantages in firepower, mobility and protection, the ability to carry them was reduced, which triggered changes to how infantry-armour fought and the ratios in which they fought together. Examples of early APC and IFV designs are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Examples of early APCs and IFVs[20]

For the US and British armies, the introduction of viable IFVs took much longer. While the introduction of the M113 in US service in 1960 (and in Australia in 1965) provided a substantial improvement over earlier APC models, experience in Korea and the early stages of the war in Vietnam highlighted several limitations inherent to the APC approach. These included a lack of firepower, limited protection against hand-held anti-armour weapons and the inability of infantry passengers to fight while mounted in the vehicle. Consequently, the US Army began to develop what they termed a ‘Mechanized Infantry Combat Vehicle’ in the early 1960s. However, its development was hindered by a range of requirement definition and resource related issues. Early attempts such as the XM701, XM734 and XM765 were derivative of the M113 and suffered from limitations in this design. A new design, XM723, suffered a protracted and painful gestation before it finally emerged as the M2 Bradley in 1979.[21] It replaced the M113 APC in US Army Mechanised Infantry units, although this vehicle was retained in certain support roles. Initially the doctrine introduced with the Bradley indicated a shift away from a generalist mechanised infantry mindset towards a specialist armoured infantry approach. However, the tension between these approaches has resulted in frequent changes in squad size and infantry trade models and in modifications to vehicle design, as well as ongoing professional debate. [22]

Comparatively, with the emergence of the BMP-1 the British Army also undertook a program to introduce an IFV commencing in 1967 termed the Mechanised Combat Vehicle 80. It also underwent a lengthy development, ultimately resulting in the FV510 Warrior in 1987. These equipped British Armoured Infantry Battalions, with Mechanised Infantry Battalions retaining the FV432 APC, a vehicle analogous to the M113. Accompanying the IFV was the adoption of a doctrine of all-arms battle groups charged with conducting highly mobile offensive actions. In previous British approaches, APCs performed the ‘battlefield taxi’ role, transporting troops close to action, where they would disembark to fight on foot—essentially as they had done in the Second World War. The new concept envisaged IFVs and tanks operating in mutual support, reinforced by the concentrated firepower of artillery and aircraft. Equipped with an IFV, the infantry could now move rapidly onto the objective before dismounting to assault at close quarters. Importantly, IFVs accompanied their infantry after they dismounted, providing them fire support and the ability to rapidly remount and move to subsequent objectives.[23]

In the early 2020s, both the US and British armies are replacing these legacy IFV fleets. After two abortive attempts—Future Combat System (cancelled 2009) and Ground Combat Vehicle (cancelled 2014)—the US aims to replace the Bradley under the auspices of the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) program. After a false start OMFV has now selected five companies to participate in a concept design phase prior to building prototypes, testing and final selection in 2027.[24] Likewise, the aged M113 APC fleet is steadily being replaced by a heavier, more protected vehicle. The US opted for the Bradley-derived Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), filling APC and support roles in their armoured formations.

The UK has been forced down a different path. The UK Ministry of Defence opted in 2021 to cancel their Warrior IFV upgrade program, instead replacing it with the wheeled Boxer Mechanised Infantry Vehicle around 2025. However, it should be noted that this was a decision based on cost rather than capability. The British Army acknowledged that the Boxer, an APC, is a different capability to the Warrior and does not ‘recreate’ the IFV capability, although it continues to investigate what might be done to ‘make it more IFV-like’.[25] In conjunction with force structure changes, the FV432 is also being replaced by the Boxer, which provides improved operational mobility and protection. There are clear economies of scale in standardising on the Boxer, which may make immediate financial sense for the UK. While the Boxer is very capable, it remains to be seen if it can compensate for the loss of the close combat capabilities of the Warrior, even when coupled with other capabilities such as artillery, helicopters and drones.

Globally, many other nations/companies continue to develop or modernise IFVs and APCs. A key driver for this is the need to increase vehicle and personnel survivability as the proliferation and lethality of anti-armour weapons increases. IFV examples include the Austrian/Spanish ASCOD, Chinese ZBD-04, German Puma and Lynx, Japanese Type 89, Indian Abhay, Italian Dardo, Russian T-15, Singaporean Hunter, South Korean K21, Swedish Combat Vehicle-90, Turkish Tulpar and US Griffin III. Likewise, APCs are steadily being upgraded or replaced in service by heavier, more protected vehicles. Late-model tracked APCs include the Israeli Namer, Russian Kurganets-25 and US AMPV; wheeled designs include the US Stryker, Russian K-16 Bumerang, Italian Super AV, Finnish Patria and German/Dutch Boxer. Late-model APC designs continue to prioritise capacity, mobility and protection over firepower.

Furthermore, the lines between APCs and IFVs have become blurred by another category of AFV, variously labelled as Infantry Carrier Vehicles or Infantry Combat Vehicles (ICVs). As a hybrid of the two, ICV designs often feature IFV levels of armament coupled with the operational mobility and capacity of wheeled APCs, often incurring penalties in weight, size or protection. Consequently, many contemporary wheeled APCs are increasingly offered as ICVs through the addition of a turret, manned or otherwise. A short survey includes the Canadian Light Armoured Vehicle 6.0, French Véhicule Blindé de Combat d’Infanterie, Israeli Eitan, Italian Freccia, New Zealand NZLAV, Singaporean Terrex, Taiwanese CM-32 Clouded Leopard, Russian K-17 Bumerang and US Stryker Dragoon. While arguments may be made that that these are simply wheeled IFVs, their typical employment aligns with a generalist approach rather than specialist methods, making a simple categorisation difficult.[26]

Similarly, the line between armoured trucks/utility vehicles and wheeled APCs has blurred with the evolution of Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPs) and Protected Mobility Vehicles (PMVs). Notable examples include the Australian Bushmaster and Hawkei, the US Mine Resistant Ambush Protected All-Terrain Vehicle andLight Combat Tactical All-Terrain Vehicle, and the UK Husky and Foxhound. While not AFVs, as they are not specifically designed for sustained close combat, protected vehicles prioritise defence against mines, improvised explosive devices and small-arms fire. They are generally equipped with defensive armament, although larger remotely operated weapons are emergent. MRAPs/PMVs often equip contemporary motorised infantry forces or serve as an expedient way to provide better mobility to traditional light or ‘foot’ infantry forces when required. Given the global efforts to update and/or acquire IFVs, APCs, ICVs and MRAPs/PMVs, it is evident that armies view the requirement for infantry firepower, mobility and protection as important and enduring. Armoured vehicles therefore remain essential tools of motorised, mechanised and armoured infantry in the 21st century. Figure 3 shows examples of contemporary vehicles.

Figure 3. Examples of contemporary PMV, APC, IFV and ICV designs[27]

Motorised, Mechanised and Armoured Infantry Philosophies

The philosophies underpinning motorised, mechanised and armoured infantry remain relevant to contemporary military forces. However, to those outside of the military the differences between them may appear indistinct. It is a neat, and oversimplified, generalisation to categorise motorised infantry as universally equipped with trucks or PMVs, mechanised infantry with APCs and armoured infantry with IFVs—this is not always so. While it is generally accurate that forces which align with an armoured infantry approach are equipped with tracked IFVs, certain armies which operate IFVs employ mechanised infantry methods and others equipped with ICVs or APCs employ them in IFV-like ways. Thus, while AFV technology is important, the way in which infantry forces are employed is definitive. Two distinct philosophies have emerged which guide contemporary armoured vehicle-borne infantry: one soldier-centric and the other vehicle-centric.[28]

The soldier-centric approach views the AFV primarily as a transport for the infantry section. The AFV transports the section to a dismount location, such as a forming-up point or short of the objective outside effective enemy weapon range; it then withdraws and remains on call to remount them once the objective is secured—the ‘battle taxi’ approach. The infantry section fight dismounted and are reliant on the fire teams within the section to provide both the base of fire and the assault elements when conducting manoeuvre. This method requires less integration between infantry and their AFV, requiring only a generalist training approach. This method is generally employed by motorised and mechanised infantry forces which deploy standard-size infantry sections requiring the lift capacities of PMVs and APCs.

The vehicle-centric approach interprets the AFV as an integral part of the infantry section providing transportation and firepower. This enables the infantry to fight mounted employing the AFV’s armament and to fight dismounted employing the AFV with the fire teams. The AFV transports the infantry to a dismount point just short of, at or beyond the objective and fights with them. It provides intimate support to the fire teams, providing the base of fire for them to move and assault—in effect the section’s ‘gun group’. Conversely, the fire teams provide intimate protection to the AFV, clearing enemy threats, particularly anti-armour weapons, in close terrain. The infantry-IFV relationship is symbiotic and is highly integrated, requiring specialised tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) to exploit the benefits offered by the IFV’s capabilities. This integration is underscored by combined-arms training at the lowest levels. This mindset is reflective of armoured infantry forces which employ smaller infantry sections tailored to their IFV.

These philosophies are demonstrated in modern Western militaries. The mechanised infantry approach is typified by US, French and Canadian forces. In contrast, British, German, Swedish, Finnish and Danish forces favour the armoured infantry pattern.[29] The New Zealand Army utilises a mounted infantry methodology, with its armoured corps providing mobility to the infantry. However, these philosophies are not monolithic. Debate continues, particularly in the US, concerning the integration of IFVs and infantry, the focus of training, squad sizes and vehicle design requirements.[30] In contrast, there appears greater consensus within armies which have adapted infantry organisations and their employment to integrate with IFVs under the armoured infantry approach. Notably, Britain’s transition to the Boxer APC from an IFV, will likely spur a review of its armoured infantry approach.[31]

In comparison the Australian Army currently fields both mechanised and motorised infantry types within its combat brigades. Both are vehicle borne and share a common basis in training, yet they operate differently. However, in the near future Army plans to replace the M113AS4 APC of the mechanised infantry with an IFV capability. Given the philosophies discussed above, the question arises: what doctrinal approach will accompany the introduction of the IFV capability? Does Army retain its current mechanised infantry concept or does it adopt an armoured infantry approach?

In the case of the former, is the IFV simply a vehicle replacement for the mechanised infantry? If so, can this be achieved without major modification to infantry structures, trade models and mechanised TTP? A generalist approach across both motorised and mechanised infantry certainly has value in achieving common battalion structures, a singular trade model and centralised training. It arguably offers greater flexibility in terms of employment, avoiding the creation of specialised requirements and posting restrictions. However, given the significant improvements in firepower, mobility, protection and communications that the IFV provides (which differ greatly from the APC and even more from the PMV), this approach risks coupling modern technology with incongruent thinking. Gunnery training, mounted TTP development and maintenance regimes may require significantly greater emphasis given the complexity of the IFV. Consequently, the benefits of a generalist approach must be weighed against the ability to maximise the potential offered by the new capability.

Conversely, what changes would be needed to under an armoured infantry philosophy? A specialist approach may require a split in infantry trade models, such as separate motorised and armoured infantry streams, akin to the armour-cavalry dynamic, which shares a common initial training base and subsequent specialisation. Equally, the capabilities of the IFV may warrant a review of the extant mechanised infantry battalion’s organisation, employment and sustainment. Given the wide number of potential IFV operators, its introduction is likely to affect more than just the infantry corps, with command and control, combat support and combat service support functions across combat brigades also impacted. Critically, the concept of how armoured infantry fight in conjunction with armour, cavalry and motorised infantry within a combined-arms setting merits examination. The impact upon the force, in terms of doctrine development, training, logistic support, facilities, capability management and development, is also likely to be significant. Therefore, in order to make this decision and maximise the potential of IFV-equipped infantry, it is important that the costs and benefits to organisation, employment and sustainment are well understood.

Figure 4. Land 400 Phase 3 contenders: AS21 Redback IFV from Hanwha Defence Australia and KF41 Lynx IFV offered by Rheinmetall Defence Australia[32]

Conclusion

The need for armoured vehicle-borne infantry was driven by the conditions faced during the First World War. Over the course of the 20th century the dynamic relationship between philosophy and technology resulted in the development of motorised, mechanised and armoured infantry types. In 21st century Western militaries two predominant distinct philosophies guide these force types. One is soldier-centric which views the armoured vehicle primarily as a transport for the infantry, enabling dismounted action through the provision of enhanced mobility while under the protection of armour. This approach requires less integration between infantry and the APC and is most applicable to generalist mechanised infantry force types. The other is vehicle-centric, viewing the infantry and their IFV as one entity. The IFV and the infantry operate in a mutually supporting manner to fight mounted and dismounted together. The IFV is essential to the infantry section as it provides them firepower, mobility and protection in close combat. This approach is highly integrated and likely warrants a specialist armoured infantry force to maximise the capabilities of the IFV-infantry team.

Two primary design trends were identified which guide APC and IFV designs. In general terms, APC designs prioritise infantry-carrying capacity, whereas IFV designs prioritise firepower. These priorities reflect the different ways, or philosophies, which guide their employment. In general terms, armies which favour mechanised and motorised approaches employ infantry generalists fighting dismounted and operating APCs/MRAPs/PMVs primarily as transports. In contrast, armies which employ armoured infantry reflect a preference for infantry specialists moving and fighting, both mounted and dismounted, in close concert with IFVs.

Given this historical context, it may be necessary for the Australian Army to examine whether a mechanised infantry or armoured infantry philosophy is the best fit as it introduces a modern IFV over the coming decade. The introduction of an IFV may warrant the adoption of a specialised armoured infantry approach to maximise the benefits this combination provides Army. Conversely, a generalist mechanised infantry approach may be more applicable if commonality across the infantry arm is sought. Both approaches have merit and both pose challenges. A perspective on the US Army’s conversion from an APC-based infantry force to an IFV-borne one 40 years ago suggests that the answer may require careful and critical analysis.

The (M-2) IFV is not an improved Armored Personnel Carrier (APC); it is truly a fighting vehicle. This is a new dimension infantrymen must master. The fundamentals of current tactical doctrine remain essentially unchanged. They must, however, be modified to capitalize on the IFV’s capabilities. The more conservative thinkers will tend to regard the IFV as an improved APC or ‘battle taxi.’ The other extreme will think of the IFV as a light tank. The correct role of the IFV is in between these Two Extremes …[33]

Finally, for some both inside and outside the military, the philosophies underpinning motorised, mechanised and armoured infantry and the differences between different types of AFVs are unclear. Consequently, this poses challenges for Army to communicate the need for armoured vehicles, particularly when faced with ill-informed and adverse commentary. To overcome this challenge, Army may benefit from explaining its philosophy for the IFV in a way accessible to government, Defence and public audiences.

Army Commentary

The delivery of the Infantry Fighting Vehicle under Land 400 Phase 3 will enable Army to realise a highly capable Land Force and the Combined Arms Fighting System. The Combined Arms Fighting System has an output far superior than the sum of its parts. It comprises infantry fighting vehicles, tanks, combat engineering vehicles, self-propelled howitzers, combat reconnaissance vehicles and helicopters. It is supported by air and missile defence, surveillance systems and an enabling logistics chain. Realising the full capability potential of this system requires replacement of the M113 platform which was first introduced into service in 1965. This platform is obsolete and no longer fit-for-purpose in response to prevalent threats in our region.

This article highlights that treating the Infantry Fighting Vehicle as a simple ‘replacement’ is not sufficient. This reality is recognised in project Land 400 Phase 3. This Phase will enable structures and systems to be put in place which realise the full capabilities of the Infantry Fighting Vehicle through an Armoured Infantry approach.

As Army continues a path of constant development, the author provides a commendable contribution to understanding Army’s past, and highlighting some of the key areas Army will see change over the coming years.

Benjamin Howard

Lieutenant Colonel

About the Author

Leo Purdy is a retired Armour Officer who served in various regimental, staff and training postings. As an independent consultant, he now undertakes research and analysis activities to support Defence and Industry capability development. In this capacity, he has written articles, studies, concepts and doctrine on armoured warfare, mounted minor tactics and the future of armour and mechanised infantry.

Endnotes

[1] While the original function of British dragoons was as mounted infantry, by the mid-17th century they had morphed into a form of heavy cavalry. R Brzezinski, 1993, The Army of Gustavus Adolphus (2): Cavalry (Oxford: Osprey Publishing), 14–16; and R Simpkin, 1980, Mechanized Infantry (London: Brassey’s Publishers Limited), 9–10.

[2] There is a tendency to conflate mounted infantry and mounted rifles which is inaccurate and hinders an understanding of their different roles, structures and equipment. The former was infantry which possessed greater mobility than foot-borne infantry but once dismounted performed the same role and functions. The latter was a form of light cavalry which performed mounted tasks such as scouting and outpost duties but fought on foot with rifles rather than fighting mounted with swords and lances as heavy cavalry. A notable example of the confusion as to the two types of forces is the Australian Light Horse. Contrary to popular opinion, they were not mounted infantry but were structured, equipped, trained and employed as mounted rifles. A Winrow, 2016, The British Army Regular Mounted Infantry 1880–1913 (London: Taylor & Francis), 1–3; and J Bou, 2010, Light Horse: A History of Australia’s Mounted Arm (South Melbourne: Cambridge University Press) 5–12 and 68–73.

[3] M Howard, 2000, The Franco-Prussian War: The German Invasion of France 1870–1871 (Oxon: Routledge), 2–4; and G Wawro, 2003, The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France 1870–1871 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 74–77.

[4] J Storr, 2010, ‘Manoeuvre and Weapons Effect on the Battlefield’, RUSI Defence Systems 13, no. 2, 61–63.

[5] H Winton, 1988, To Change an Army: General Sir John Burnett-Stuart and British Armoured Doctrine, 1927–38 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas), 13–16.

[6] D Fletcher, 2016, British Battle Tanks: World War I to 1939 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing), 31, 42, 61, 64, 86 and 152.

[7] R Ogorkiewicz, 1974, ‘Mechanized Infantry’, Military Review 54, no. 8, 67–69.

[8] N Thomas, 2017, Osprey Elite 218: World War II German Motorised Infantry & Panzergrenadiers (Oxford: Osprey Publishing), 5–10; and Steven Zaloga, 1994, Osprey New Vanguard 11: M3 Infantry Half-Track 1940–73 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing), 3–5.

[9] M Hughes and C Mann, 2000, Fighting Techniques of a Panzer Grenadier 1941–1945 (London: Cassell & Co), 25–29; G Rottmann, 2009, World War II US Armored Infantry Tactics (London: Osprey Publishing) 40–53 and S Zaloga, 2017, Osprey Combat-Panzergrenadier versus US Armored Infantryman (London: Osprey Publishing), 18–20.

[10] S Dunstan, 1984, Osprey Vanguard Number 38 Mechanised Infantry (London: Osprey Publishing), 3–4; and J Grodzinski, 1995, ‘“Kangaroos at War”: The History of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment’, Canadian Military History 4, no. 2, 23–50.

[11] Department of the Army, 1962, Field Manual 7-20 Infantry, Airborne Infantry, and Mechanized Infantry Battalions (Washington: Headquarters Department of the Army), 287–289.

[12] R Hunnicutt, 1999, Bradley: A History of American Fighting and Support Vehicles (Novato: Presidio Press), 249–285.

[13] B Perret, 1984, Osprey Vanguard Number 38 Mechanised Infantry (London: Osprey Publishing), 23–29.

[14] Image created by author.

[15] Simpkin, 1980, 18–19 and 25–30.

[16] P Blume, 2003, Tankograd Militärfahrzeug Spezial N 5002: The Early Years of the Modern German Army 1956–1966, (Erlangen: Tankograd Publishing), 48–51; and Ogorkiewicz, 1974, 70–71.

[17] Blume, 2003,pp 48–51; and RA Coffey, 2000, Doctrinal Orphan or Active Partner? A History of U.S. Army Mechanized Infantry Doctrine, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College), 4.

[18] S Zaloga, 1994, Osprey New Vanguard 12 BMP Infantry Fighting Vehicle 1967–1994 (London: Osprey Publishing), 3–6.

[19] Coffey, 2000, 4–10; B Held, M Lorell, J Quinlivan and C Serena, 2013, Understanding Why a Ground Combat Vehicle That Carries Nine Dismounts Is Important to the Army (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Arroyo Center), 7–8; and Simpkin, 1980, 22–32.

[20] Images created by author from open sources.

[21] Burton, Hawarth and Hunnicutt provide detailed explanations of the development of the M2 Bradley IFV in the US Army and the challenges it encountered. JG Burton, 1993, The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press); WB Hawarth, 1999, The Bradley and How It Got that Way: Technology, Institution, and the Problem of Mechanised Infantry in the United States Army (Westport: Greenwood Press); and Hunnicutt, 1999, 249–285.

[22] Examples of this debate include F Abt, 1988, Tactical Implications of the M2 Equipped J-Series Mechanized Infantry Battalion, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); JM Carmichael, 1989, Devising Doctrine for the Bradley Fighting Vehicle Platoon Dismount Element: Finding the Right Start Point, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); Coffey, 2000; BC Freakley, 1987, Interrelationship of Weapons and Doctrine: The Case of the Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); E Gibbons, 1995, Why Johnny Can’t Dismount: The Decline of America’s Mechanized Infantry Force, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); B Jones, 1995 Cutting the Foot to Fit the Shoe: The Organization of The Bradley Battalion and the 1993 Version of FM 100-5, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); DH Ling, 1993, Combined Arms in the Bradley Infantry Platoon, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); T Severn, 1988, AIRLAND Battle Preparation: Have We Forgotten to Train the Dismounted Mechanized Infantryman?, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); RJ St. Onge, 1985, The Combined Arms Role of Armored Infantry, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); C Tucker, 1992, The Mechanized Infantry Battalion: Is Change Necessary?, Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College); H Wass de Czege, ‘Three Kinds of Infantry’, Infantry, July-August 1985, 11–13; and H Wass de Czege, ‘More on Infantry’, Infantry, September-October 1986, 13–15.

[23] S Dunstan, 1998, Warrior Company (Europa Militaria No 25), (Ramsbury: The Crowood Press Ltd), 4.

[24] There are five companies participating in the concept design phase: American Rheinmetall Vehicles, BAE Systems, General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS), Oshkosh Defense, and Point Blank Enterprises. A Feickert, 2021, The Army’s Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, Updated December 28, 2021, R45519 Version 22 (Washington: Congressional Research Service), 1–7, at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45519

[25] H Lye, ‘British Army Outlines How Boxer Will Fill Warrior Capability Gap’, Army Technology, 7 May 2021, accessed 6 January 2022, at: British Army outlines how Boxer will fill Warrior capability gap - Army Technology (army-technology.com)

[26] A notable point of difference in US doctrine between Bradley and Stryker equipped units is when they dismount. Except when facing light opposition, Stryker units plan to dismount in points of cover out of the maximum effective range of enemy weapons—e.g., they move to battle, dismount in cover in an attack position (forming-up position) and commence the assault on foot. Bradley-equipped mechanised infantry manoeuvre to an assault position (a bound in the assault itself) and may dismount at that point in range of the enemy weapons. Maneuver Center of Excellence, 2016, Army Training Publication 3-21.8: Infantry Platoon and Squad (Fort Benning: Headquarters Department of the Army), 2-57, 2-92 and 2-93.

[27] Images created by author from open sources.

[28] See P Kasurak, 2020, Canada’s Mechanized Infantry: The Evolution of a Combat Arm, 1920–2012, (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press), 4–5 for further discussion on these two philosophies.

[29] Ibid.

[30] This topic has been the subject of frequent debate, illustrating the ongoing tension over infantry and IFV integration and organisation. In addition to the sources raised in endnote XV, useful examples of this debate are provided in Held et al., 2013; and R Van Wie and T Keyes, ‘Mechanized Infantry Experience and Lethality: An Empirical Analysis’, Infantry, Summer 2019, 15–19.

[31] Lye, 2021.

[32] Image sourced from the Department of Defence image gallery, accessed 10 January 2022, at: http://images.defence.gov.au/20210312adf8588365_7224.jpg

[33] C Lee, 2004, The Challenges in Training of the Mechanized Infantry Units of the Republic of Korea Army in Transitioning from the Armored Personnel Carrier (K200) to Infantry Fighting Vehicle (K21), Master’s thesis (Fort Leavenworth: United States Army Command and General Staff College), 9.