A 100-year-old bullet-riddled steel landing craft recovered from Gallipoli is one of the first items seen by visitors to the Australian War Memorial, furnishing silent testimony to the Australian Army’s lengthy amphibious tradition. This heritage includes several division- and corps-level amphibious and littoral operations across the South-West Pacific during the Second World War. However, despite some important capability acquisitions, the recent experience of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has led to ‘amphibious amnesia’—existing force structures and operating concepts are ill-suited to waging high-intensity littoral warfare. Australia’s new littoral manoeuvre concept represents an opportunity for the ADF to better support ‘whole of government’ efforts to shape, deter, and respond to threats in the region.[1] Within the new littoral project, one development option promises a multitude of benefits. Weaponising the Army’s future fleet of littoral vessels with loitering munitions will offer operational and tactical flexibility to the joint force, support high-intensity littoral warfare and, for the first time, see the Army play a role in strategic deterrence.

This article proceeds in four parts. First, it outlines the current strategic framework, defines Australia’s regional maritime geography and primary operating environment, and highlights the Australian Army’s experience in conducting effective large-scale amphibious and littoral operations. Second, it reviews the Australian Army’s watercraft replacement program and the current discourse surrounding the littoral manoeuvre concept, assessing that there is no technical or doctrinal barrier to weaponising the future fleet. Next, it explores the characteristics and operational use of loitering munitions and surveys their integration into the nascent United States Marine Corps (USMC) organic precision fires (OPF) program. The article then concludes with a simple proposal: that the Army’s future watercraft be fitted for such weapons, offsetting critical gaps in ADF capability and providing the joint force with enhanced lethality and protection at the tactical and theatre levels.

Strategic Context and ‘Amphibious Amnesia’

Australia’s strategic risks are rising as the preponderance of global wealth and power shifts to maritime Asia. The Department of Defence’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update (DSU) identified the growing threat of China and argued for a significant change in strategy. Australia’s primary focus shifted from the Middle East towards the Indo-Pacific—a distinctly maritime operating environment. It narrowed strategic guidance for force structure, prioritising ‘credible capability to respond to any challenge … in the immediate region’.[2] The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) reaffirmed much of the DSU, defining Australia’s ‘immediate region’ as ‘encompassing the north-eastern Indian Ocean through maritime South-East Asia into the Pacific, including our northern approaches’.[3] This region is dominated by thousands of islands across vast archipelagos and a growing population concentrated on long coastlines.

Despite the clear maritime focus of both the DSU and the DSR, Professor Michael Evans has observed that a curious paradox of Australian strategic culture is the lack of any significant maritime tradition. Even though the ANZAC sacrifice on the beaches of Gallipoli—the largest amphibious operation of the First World War—looms large in the Australian national identity, Evans argues that neither amphibious campaigning nor a general maritime consciousness has ever come to define strategic thought. Even the numerous division- and corps-level amphibious operations performed in New Guinea, New Britain, Bougainville and Borneo between 1943 and 1945 have not found their way into the national ‘strategic psyche’.[4]

Yet, as Russell Parkin argues, in recent decades every time Australia has faced a genuine crisis it has repeatedly deployed its military in an ad hoc reaction rather than as part of a coherent strategic policy. These responses have always required the projection of forces ashore, a task for which such forces are often ill prepared. Sea power can project, protect, and sustain land forces, but only land forces can take and hold territory.[5]

Australia’s defence policy is often framed within a ‘continental’ versus ‘expeditionary’ framework, a dichotomy that has dominated much of debate since the 1970s. Evans remarked that this debate often oscillates between ‘the defence of geography on one hand and the defence of interests on the other’.[6] In one sense a false dilemma, this dichotomy is nevertheless a useful way to broadly explain Australia’s ‘ways of war’ and its strategic continuity.

‘Continentalism’, the first way of war, is best represented by the ‘Defence of Australia’ (DOA) doctrine, a thoroughly geographic conceptualisation of national security best typified by Paul Dibb’s contribution to the 1987 Defence White Paper. Dibb interpreted the 2020 DSU as a return to the DOA concept following decades of commitment in the Middle East and Central Asia, but with an important distinction: the contemporary strategic situation is more dangerous and uncertain than the benign regional environment of the 1980s.[7] Evans, however, argues that this is a conceptually narrow strategic view where the sea is viewed as a ‘defensive moat’ rather than manoeuvre space.[8] This approach is focused on defending the northern ‘air-sea gap’, an unfortunate term which obfuscates the complexity of the littoral and archipelagic region within: a joint land-sea-air operating environment.[9]

The second way of war involves an expeditionary approach to strategy, which seeks maritime security through alliance with a great naval power. This means paying premiums to a security guarantor through regular deployments of force packages to distant offshore theatres, most recently in Afghanistan and Iraq. Evans points out that the Australian way of war has an ‘offshore character’, while historian Jeffrey Grey noted that Australia’s warfighting approach has always been defined by the high quality of its expeditionary infantry.[10] But this strategy has hitherto meant there has been both minimal requirement and limited opportunity to develop a sovereign maritime tradition.

The maritime manoeuvre potential of a new fleet of Army-operated vessels represents an opportunity for new thinking on operating concepts and force design. But it should be noted that the Army’s current strategic focus is not unprecedented. In the Second World War the Australian Army conducted extensive operations across multi-year campaigns, on land and along coastlines, as part of a coalition maritime strategy in the same region defined by the 2023 DSR. Apart from the larger and better-known landings at Lae in 1943 and across Borneo in 1945, Australia conducted dozens of amphibious and littoral operations in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) in the Second World War.

During this period the Australian military developed extensive experience conducting what could now be called ‘littoral operations’. In late 1943, under Operation POSTERN, the 9th Division conducted two significant amphibious operations in succession at Lae and Finschhafen, then cleared the coastline of the Huon Peninsula as part of General Douglas MacArthur’s CARTWHEEL plan.[11] To support POSTERN, US Navy motor torpedo boats (or ‘patrol torpedo’—‘PT’—boats) blockaded the Huon Gulf and twin Vitiaz and Dampier straits, hunting Japanese transports along the New Guinea littorals.[12]

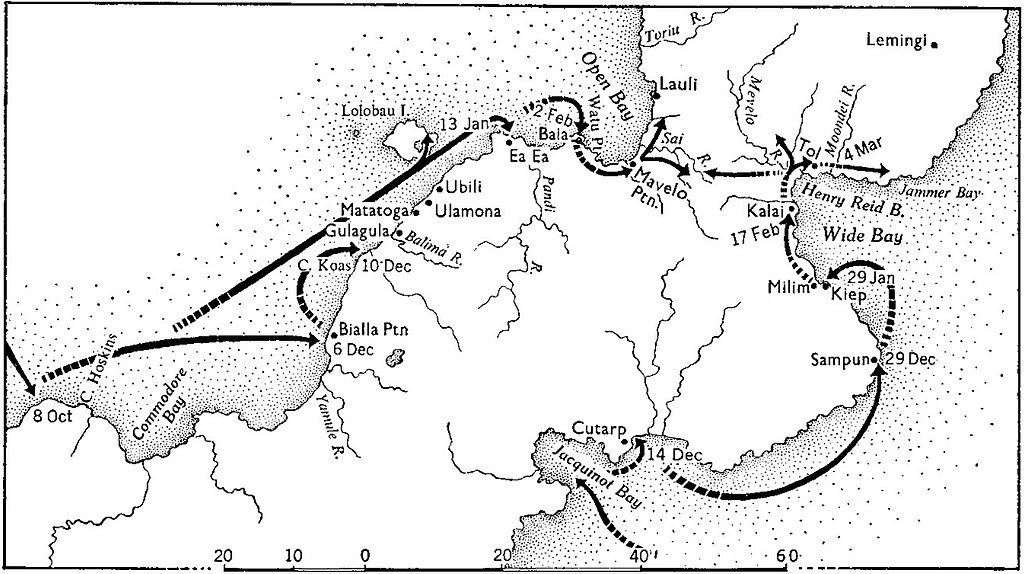

When the Australian 5th Division arrived in New Britain in October 1944, it used barges to launch a series of two-pronged advances along the north and south coasts towards the neck of the Gazelle Peninsula to fight and contain a Japanese army of nearly 70,000 men, many seasoned veterans, until the end of the war.[13] In May 1945, under Operation DELUGE, an amphibious ‘end-run’ enabled Farida Force, a Commando Regimental Combat Team, to envelop and isolate the Japanese positions at Wewak for their destruction by the 6th Division during the Aitape-Wewak campaign.[14]

In June 1945 as part of Operation OBOE 6, Brigadier Victor Windeyer’s 20th Brigade conducted patrolling operations by using landing craft to move quickly along the various rivers and estuaries along the North Borneo coastline.[15] Place names like Dove Bay, Goodenough Island and Scarlet Beach may not hold as much resonance as Gallipoli, but they nonetheless represent a journey of doctrinal development, innovation, and institutional competence earned by hard-won experience.

Map 1. Australian operations in central New Britain, October 1944 to March 1945 (Source: Australian War Memorial)[16]

At one stage, the Army operated a veritable armada of boats and small craft, including trawlers, tugs, lighters, dinghies, barges, landing craft, and the 1,500-ton supply ship Crusader. Towards the end of the Second World War, the Army’s Water Transport units operated over 2,000 ships and small vessels between Australia, New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Borneo.[17] This stands in stark contrast to the two-dozen watercraft currently in service.

While planners should indeed seek lessons from the past, it is important that the warfighting potential of the new watercraft be optimised for the future. In a critique of US defence policy, Christian Brose lamented procurement incentives that favoured ‘better legacy platforms over integrated networks of faster kill chains [and] familiar ways of fighting over new ways of war’.[18] Australian former naval officer Bob Moyse expressed similar sentiments about Australia’s force structure debate:

By concentrating on getting better at what they already do well, the army, navy and air force risk missing the point, like whales trying to solve their problems by getting bigger or cheetahs by getting faster.[19]

He adds: ‘no one has ever won an archipelagic conflict on a single landmass. Archipelagic warfare depends upon manoeuvre of land forces by sea’.[20] The Australian Army’s littoral manoeuvre programs (Land 8710 and Land 8702) present the opportunity to ensure legacy vessels are not simply replaced with newer ones, and that the future force is capable of littoral manoeuvre, joint warfighting, and strategic deterrence.

Littoral Manoeuvre

The DSU’s partner document, the 2020 Force Structure Plan, announced the Army’s intention to replace its fleet of aged watercraft. Land 8170 Army Littoral Manoeuvre (Phase 1) seeks to replace the Army’s dated Landing Craft Mechanised (LCM-8) as well as its Lighter, Amphibious Resupply, Cargo, 5-ton (LARC-V) watercraft. The Littoral Manoeuvre Vessel—Medium (LMV-M) will be replaced with an improved but similar capability. Phase 2 will procure a heavy landing craft to re-establish the capability of the decommissioned Balikpapan-class Landing Craft Heavy (LCH). An LCH is an essential platform to disaggregate a landing force from the large and few Canberra-class Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) vessels and enhance survivability in a contested maritime domain. Under Project Land 8702, the Army will deliver a littoral and riverine fighting vessel, tentatively termed the Littoral Manoeuvre Vessel—Patrol (LMV-P). The ADF has never fielded an LMV-P type capability, so its requirements are loosely defined. Therefore, great opportunity exists to maximise the project’s operational potential.

Figure 1. Concept art for Raytheon-BMT proposed Independent Littoral Manoeuvre Vessel (ILMV). If selected to deliver the Army’s Land 8710 Phase 1A program, Raytheon Australia will lead the team to deliver the BMT-designed vessel. The ILMV is one of several proposals for Land 8710 Phase 1A (Source: Australian ILMV design, BMT)[21]

Figure 2. Concept art for the Australian Maritime Alliance (AMA) proposed ‘Oboe’ design. The Oboe is one of several proposals for Land 8710 Phase 1A (Source: Serco)[22]

Figure 3. HMAS Balikpapan, East Timor (Source: Defence Image Gallery)[23]

Several Australian commentators have offered views on the embryonic littoral manoeuvre concepts. Professor Peter Dean recently called for restructuring the Marine Rotational Force—Darwin from a conventional bilateral training activity to one centered on experimentation and on developing the USMC’s emerging littoral operating concepts alongside Australia’s own Indo-Pacific focus. He notes that Washington’s adoption of ‘integrated deterrence’ as the ‘cornerstone’ of its Indo-Pacific Strategy makes the interoperability of its nascent littoral concepts with the ADF essential.[24] Furthermore, Dean argues, the US Navy Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System (NMESIS), with its use of the Joint/Naval Strike Missile (NSM), nests neatly with Project Land 8113 Long Range Fires and SEA 4100 Phase 2 Land Based Maritime Strike.[25]

Will Leben offers a ‘radically different force design’ and operating concept intended to ‘deter without escalation’. Specifically, he presents a model of a dispersed maritime-littoral task group based on Army capabilities and ‘latent strike’. He proposes the emplacement of Army command and control (C2); intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); and strike capabilities within a maritime area of operations (AO) at the onset of a crisis—perhaps as a stay-behind force following a disaster relief operation, as part of a routine training rotation, or as circumstances deteriorate along a ‘competition continuum’. ‘We need to offer a credible vision of how we could employ joint forces to shape a threat in a maritime setting’, he says, ‘rather than merely targeting them after they have acted first.’[26] Though his draft proposal pre-dated his awareness of its existence, his paper echoes much of the thinking behind the USMC’s Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept. This is unsurprising given the shared strategic focus and similar operational challenges.

Historian Albert Palazzo calls for new thinking on the purpose of the Army’s future watercraft. He points out that to date, the operational usage of the Army’s watercraft has been nearly entirely limited to the support of forces ashore, including the movement of personnel, stores and vehicles, typically intra-theatre. ‘When the soldiers needed fire support from the sea they had to call upon the navy’, he says. ‘The Army’s watercraft mission was to support the fight, not to undertake it.’ He proposes that Land 8710 evolve as a combat as much as a support program, integrating other joint fires projects with the littoral manoeuvre potential of the Army’s new boats. ‘There is no longer a good operational or technological reason’, he adds, ‘to treat Army boats solely as support vessels’.[27]

Other states field fleets of potent small craft. Examples include the Hellenic Navy’s Roussen-class fast attack craft, the Norwegian Skjold-class missile corvette, the Finnish Hamina-class missile boat, the Israeli Sea Corps Sa’ar 4.5-class missile boat, and China’s Type 022 Houbei stealth missile boat. The Iranian Navy’s doctrine includes ‘swarming attacks’ conducted by small, fast boats hidden among littoral inlets and anchorages. These micro fleets launch concentrated anti-ship missile strikes from dispersed locations that seek to overwhelm an adversary’s missile defence system.[28] While these vessels are operated by navies, Australian Army personnel or joint crews could equally operate the ADF’s future brown-water fleet.

As it is not expected to transport large cargo or vehicles, the Australian Army’s LMV-P project presents an opportunity for renewed thinking on the future littoral and riverine capability. A small platform generates unique manoeuvre opportunities. As Palazzo argues, the Army’s future watercraft ‘will not sail in blue water and do not need long sea legs. Instead, they will hug the shore and hide in coves and swamps or move upriver’.[29] Weaponised vessels could be the brown-water equivalent of Julian Corbett’s ‘flotilla’ with a ‘battle power’ that asymmetrically holds an adversary’s vessels and other critical systems at risk.[30]

The PT boats of the Second World War offer an example of the value of small, agile and well-armed vessels in high-intensity littoral warfare. Their experience suggests that the Army’s future watercraft should not duplicate the role performed by the Navy’s larger offshore patrol vessels or warships. As the US Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison explained, PT boats were originally designed to ‘sneak up on enemy warships at night and torpedo them’, but this turned out to be ‘suicidal’ at Guadalcanal.[31] Instead, they found a new purpose and proved indispensable along the coasts of New Guinea, New Britain and the Admiralty Islands.

Because of Allied sea control in adjacent waters, Japan’s alongshore barge traffic became its only surface supply line. In the South-West Pacific littorals, PT boats ran nightly patrols in search of enemy barges, denied waterborne transport to the Japanese, inserted and extracted scouting parties, and provided fire support to amphibious operations.[32] From 1942 to 1945, expanding from a force of six boats to 15 squadrons, PT boats and their rockets, torpedoes, cannons, and machine-guns left coastlines littered with destroyed barges and starved enemy soldiers.[33]

But what types of modern weapons are suitable for littoral watercraft? Apart from direct fire support, Palazzo has campaigned for very long-range precision-fire systems that would allow the Army to adopt its first strategic mission.[34] Such systems would undoubtedly require robust joint battle networks for ISR and targeting. Jason Kirkham argues for an Australian ‘deep battle’ concept to act as a unifying framework to rationalise upcoming long-range systems acquisition.[35] Former Commanding Officer School of Artillery Ben Gray cautions against the ‘seductive and enticing’ allure of a doctrine predicated exclusively on precision systems, a cultural proclivity fueled by wars of choice and a desire for ‘quick solutions’ and intangible threats. Mass artillery fire, he emphasises, is still necessary to mitigate manoeuvre vulnerabilities.[36] For this effect, the Army’s Project Land 8116 Protected Mobility Fires will deliver a regiment of self-propelled artillery and, in due course, be augmented by additional High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems.[37] But these are terrestrial capabilities that require lodgement ashore for their effects to be brought to bear.

Loitering munitions offer an alternative: a middle ground that balances precision (strike) with mass (the ability to swarm), cross-echelon networked fire control, and the ability to deploy afloat on future watercraft. There is currently no ADF project to introduce loitering munitions into service—but there should be.

Loitering Munitions

Loitering munitions fit in the niche between cruise missiles and unmanned combat aerial vehicles—both capabilities the ADF either currently fields or is developing.[38] Sometimes called ‘kamikaze drones’ or ‘suicide drones’, loitering munitions are a low-cost, and thus potentially high-density, unmanned vehicle, armed with explosives and designed to ‘loiter’ above a target area for an extended period.[39] Like a missile, they are a one-time consumable designed to find a target and strike it. Humans can steer them from a control station, they can be autonomously operated with pre-programmed strike authority, or they can be employed with a combination of both.[40] Their ongoing development envisions the application of swarming methods to overwhelm an adversary’s defences.[41] One analyst has called loitering munitions ‘a revolution in plain sight … [one] that will impact the character of warfare more substantially than the introduction of the machine gun’.[42]

While they have their origins in the Second World War era jet revolution, loitering munitions matured in the 1980s as a specialised weapon to target anti-aircraft systems. Several programs such as the Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI) Harpy and US AGM-136 Tacit Rainbow integrated anti-radiation sensors into a drone or missile frame. These capabilities were designed to be launched in sufficient numbers to saturate enemy surface-to-air missile areas and trigger activation of radar systems for attack by follow-on aircraft. As aerodynamics, C2, and payload technology have improved, loitering munitions are increasingly used as a substitute for everything from mortars to airstrikes. The Marine Corps, for example, is seeking to directly replace its 120 mm mortar capability with loitering systems.[43] Some loitering munitions rely on a human operator to locate and strike targets, whereas others, such as the IAI Harop, can function autonomously.[44] Loitering munitions have appeared in war zones such as Afghanistan, Yemen and Syria, but it was not until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War that they garnered mainstream attention.[45]

In 2020, in a brief war over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, Azerbaijan overwhelmed the Armenian military with the Harop loitering munition, enjoying success against older ground-based air defence systems. This tactic peeled off an important defensive layer, gave Azerbaijan air supremacy, and allowed it to destroy armoured vehicles and other systems with relative ease.[46] The Harop provided an almost persistent air threat to Armenian forces with its nine-hour loiter time and top-down anti-tank capability.[47] With off-the-shelf munitions, Azerbaijan demonstrated, according to one commentator, ‘how a modest technological advantage can turn into a major strategic benefit’.[48]

The 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War propelled loitering munitions to notoriety. As of February 2023, the US Department of Defense has supplied Ukraine with 700 AeroVironment Switchblade Tactical Unmanned Aerial Systems (T-UAS) and 700 Aevex Aerospace Phoenix Ghost T-UAS.[49] Mainstream media outlets have widely promulgated demonstrations of their capabilities.[50] The Russian military has made extensive use of ZALA Aero Group’s Lancet-1, Lancet-3 and KUB-BLA small loitering munitions, with a 1 to 3 kilogram payload and 30 to 40 minute endurance; and the larger Geran-2, which houses a 30 to 50 kilogram warhead. They are routinely recorded destroying Ukrainian air defence and long-range fires platforms.[51] In addition, the conflict has showcased ‘suicide’ unmanned surface vessels (USVs) and the destruction of naval vessels with aerial loitering munitions, demonstrating the utility of autonomous munitions in the maritime domain.[52]

Nations with advanced drone programs generally possess sizeable loitering munitions arsenals. China, Russia, Iran, Turkey, Israel, Taiwan, and the United States all have domestic loitering munition production, and several other nations have purchased them from major manufacturers.[53] The battlefield events in Ukraine are driving a surge in demand for unmanned systems and the threshold for entry, even for non-state actors, is inexpensive.[54] At the time of writing, Australia does not yet have a loitering munition program for either domestic production or supply.

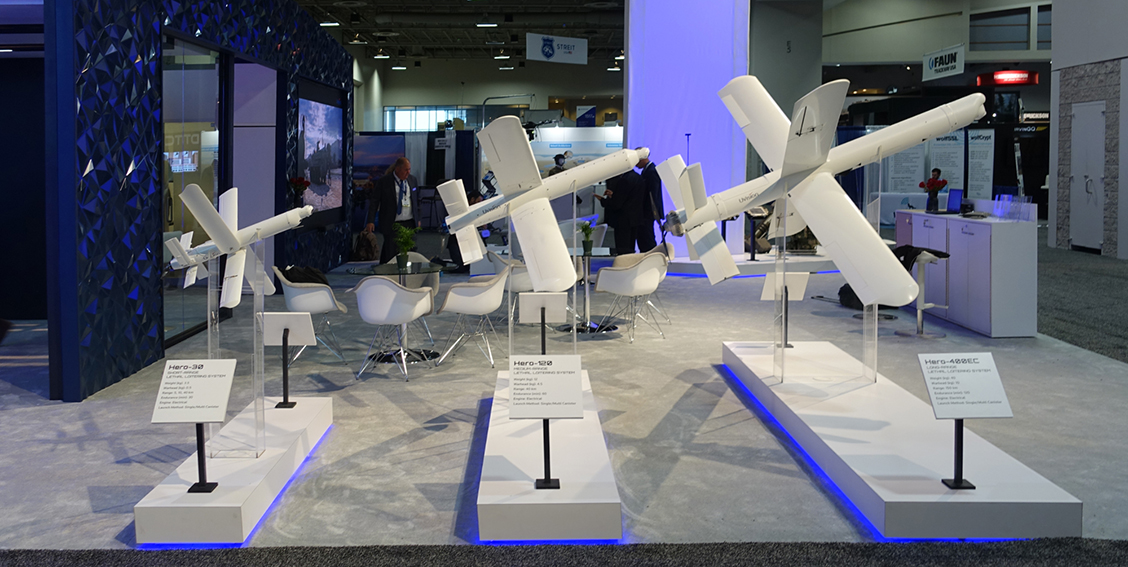

In 2021 the USMC contracted the Israeli-made Hero-120 loitering munition for its Organic Precision Fires—Mounted (OPF-M) systems requirement. UVision’s contract followed a request from Marine Corps Systems Command (MARCORSYSCOM) for a tactical precision fires system ‘capable of attacking targets at ranges exceeding the ranges of weapons system currently in an organic infantry battalion [7 kilometres] and up to 100 kilometers’.[55]

UVision’s Hero suite ranges from tactical to strategic systems, but the Hero-120 is the only platform acquired by the USMC so far. UVision advertises the munition as suitable for tactical tasks ‘and other strategic missions’, and it is the largest of their short-range systems. At 18 kilograms, it carries a 4.5 kilogram warhead, and its electric engine can project it beyond 60 kilometres for about an hour.[56] UVision’s smallest system is the Hero-30, a man-portable TUAS weighing 7.8 kilograms (with launcher), a half-kilogram warhead, a 15 kilometre range, and a 30-minute loiter time. The largest strategic system is the Hero-1250, comparable to the Geran-2 with a 30 to 50-kilogram warhead, a 200 kilometre range, and 10 hours of endurance.

Figure 4. UVision loitering ammunition models Hero-30, Hero-120 and Hero-400EC (Source: Wikimedia Commons)[57]

The OPF-M contract provides for a multi-year program in which UVision will supply the Hero-120 loitering munition to the USMC. UVision pitches Hero-120 as a system that combines surveillance and attack capabilities in a semi-autonomous system, defeats multi-dimensional threats in complex battlespaces, operates in GPS-denied environments, enables transfer of fire control between echelons, and communicates with existing C2 and fire-control systems.[58] If it proves capable of networking with the Aegis combat system, land-based C2 suites, or other existing battle networks, it will have immediate utility for the ADF.

For the USMC contract, Hero-120 will come with a multi-canister launcher, which is currently configured in eight cells but is modular and can be adapted to four- or six-cell configuration as required. It can be integrated into the USMC’s Light Armored Vehicle-Mortar, the 4x4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, and the Long-Range Unmanned Surface Vessel.[59]

Figure 5. Long- Range Unmanned Surface Vessel with Multi-Canister Launcher (Source: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service)[60]

This article does not advocate for a specific platform or market solution.[61] However, it highlights the Hero munitions for several reasons. First, Hero-120 presents a model with a promising array of capabilities, including effective operating ranges suitable for the littoral environment. It is a multi-mission system designed for the air, land and sea, and thus represents an example of potential cost efficiencies and cross-domain synergy. UVision advertises its maritime capabilities as ‘sea-to-sea’ and ‘sea-to-shore.’[62]

Second, the Hero suite spans the range of tactical to strategic systems in payload, ranges, launch platforms, and mobility, representing opportunities for cross-echelon target selection and hand-off in an integrated fire-support network. Any loitering munition acquisition should consider efficiencies in manufacturing, supply chains, and operator training.

Third, Australia’s closest ally has selected the Hero-120 system for the USMC OPF-M project, which intends to employ it in distributed maritime operations. Given the maritime nature of Australia’s primary operating environment, the ADF and USMC both face similar operational problems.

Weaponising Watercraft

The DSR is explicit on the importance of Australia’s regional geography in framing the ADF’s military challenge. The littoral manoeuvre concept and watercraft replacement program are acknowledgements of the growing significance of the maritime operating environment. But unarmed, the future vessels will only address half the problem—manoeuvre without fire.

Artillery and mortar fire provide massed but imprecise support to the manoeuvre element, and precision fires have traditionally been the role of manned aviation. Yet in the degraded, distributed, and denied environments of the Indo-Pacific littorals, there is a pressing need for long-range precision fires available to smaller manoeuvre units dislocated from each other and their supporting echelons. This capability becomes crucial if these manoeuvre elements are operating in an adversary’s weapon engagement zone, acting as ‘stand-in forces’ in Marine Corps parlance.[63]

In a conceivable future war against a peer adversary, it is unwise to assume that elements of the joint force will have ready access to close air support or naval surface fires from large, targetable warships. From 1942 to 1943, following the battles of the Coral Sea, Midway, and the Bismarck Sea, the dispersed Japanese Eighth Area Army in the South-West Pacific increasingly found itself at the mercy of Allied air and sea power, relying on submarines and alongshore barges, mostly moving by night, for reinforcement and resupply.[64] Similarly, a ‘stand-in force’ operating forward in the contemporary maritime environment will often be reliant on its organic fire support. Commanders will require a responsive and organic precision strike capability to achieve their tasks and protect their force. Ideally, this capability should be inexpensive, multi-purpose, long range, and electronically resilient.

Fortunately, loitering munitions offer such a capability, as the Marine Corps has recognised. Loitering munitions are cheaper than missiles, low signature, and simple to operate. They combine the benefits of independent fire support with ISR capabilities, and they also allow forces to locate, track, prioritise, hand off, or engage time-sensitive targets. Concentrated munitions launched from dispersed locations in sufficient numbers can overwhelm and dismantle an adversary’s anti-access air defence system. The Nagorno-Karabakh, Russo-Ukrainian, and Israel-Hamas wars have all so far failed to produce a suitable response to loitering munitions.[65] Thus, low-signature distributed stand-in forces and small littoral vessels can conceivably degrade an opponent’s air defence system from within the weapon engagement zone, buying time and space for larger conventional joint assets to enter the battlespace. As one commentator put it: ‘Formerly the domain of higher echelon shaping operations, enemy armour and air defense assets can now be swept off the battlefield chessboard by a company-level drone strike.’[66]

The Australian Army should arm its future littoral watercraft with loitering munitions. The best opportunity to do so is at the outset of the littoral manoeuvre watercraft replacement program, before designs are finalised. The Army does not need to develop separate vessels for its various missions. Less the specific requirements of the LMV-P, the same LMV-M hull could provide the base for troop transport, cargo and supply, riverine and coastal patrol, fire support, and C2. The LMV-P itself could house a series of different mission kits or weapon pods. Other militaries field modular weapon kits and containerised systems. As the Marine Corps is demonstrating, the Hero canister launcher can be mounted on various vehicles and vessels. Both Russia and China have developed cruise missile systems disguised in 40-foot shipping containers, giving merchant vessels the ability to strike aircraft carriers and complicate targeting.[67]

Deception aside, the availability of heavier and more advanced munitions with extended range—200 kilometres in the case of the Hero-1250 system—presents the Army with the option to significantly expand its organic operational fires reach. Along with the acquisition of land-based long-range strike capabilities such as the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System and Lockheed Martin’s Precision Strike Missile, long-range loitering munitions enable Army to assume responsibility for securing maritime terrain within Australia’s northern approaches, acquiring a deterrence role at the strategic level of war. Along with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and Royal Australian Navy (RAN), the Army’s strategic mission could entail contesting an adversary’s manoeuvre across a theatre-sized battlespace—the vast littoral region to Australia’s north and north-east.[68] These long-range weapon systems could be ground-based, flown in by air, or launched from the Army’s future watercraft.

Figure 6. Swedish-designed Stridsbåt 90H CB90-class fast assault craft. Rheinmetall and UVision offer the CB90 as a conceptual example for marketing the Hero-120 in the maritime domain (Source: Wikimedia Commons)[69]

There are several operational and strategic advantages to loitering munitions afloat. First, the littoral operations concept is designed to enhance Australian deterrence signalling within a sovereign escalation framework. Currently, the ADF’s staging and deployment of a capital ship, such as the Canberra-class LHD, or a larger embarked amphibious task force, represents a significant escalation for Australia. There are limited steps on such an escalation ladder, and further signalling requires substantial commitment of additional forces. The presence of smaller watercraft, on the other hand, lowers diplomatic costs and increases the number of rungs on the ladder. Small patrol boats are likely to be more politically palatable to Indo-Pacific heads of state than are warships.

Second, at the tactical and operational level, the ability of a littoral task force commander to employ a dense array of sensors prior to ground force disembarkation provides essential organic surveillance support to the force. This is the case for large amphibious lodgements, littoral patrolling, or pre-landing force operations. The simultaneous ability to remove threats as they appear, or to prioritise them for higher echelon targeting, enhances that flexibility and security. LMVs could discharge smaller ‘kamikaze’ USVs—like those purportedly used against the Russian Black Sea Fleet by Ukraine in 2022 or those launched against the Saudi Arabian Navy by Houthi rebels in 2017—for further self-defence or offensive strike capability.[70] In addition, most loitering munitions feature the ability for the operational commander or system operator to abort a strike mission mid-flight.

Third, the flight endurance of loitering munitions adds a temporal advantage that is significantly different from any other weapon system in operation. Loitering endurance means ‘greater range, greater effects density, and greater survivability for the launch platform which can be long gone before the munition it delivered engages its target’.[71] Watercraft possess the advantage of unimpeded manoeuvre, fast powered movement, and the ability to hide in complex terrain afforded by the littoral shore, including coves, estuaries and inlets.

Fourth, the combination of technical simplicity and precision offers the opportunity to push offensive support to lower echelons under permissive fire-control methodologies. This would mean greater organic survivability and lethality—loitering munitions are as much a force-protection system as a fires asset in a denied environment. Human-operated abort options and artificial intelligence enabled autonomous munitions decrease response time, increase strike accuracy, and minimise human error and collateral damage. These characteristics enable commanders to assume greater risk in decentralised fire control. This targeting approach will be essential in any future conflict within the Indo-Pacific, where the ‘tyranny of distance’ will see distributed forces operating in remote and austere locations without the advantage of immediate on-call fire or air support, even should their communications not be denied by their adversary.[72]

Fifth, loitering munitions add to the growing mixed arsenal of lethal and capable weapon systems employed by the ADF. When instantaneous protective fires are required, missiles and conventional artillery remain more effective. However, loitering munitions provide a complementary weapon mix by generating a greater proportion of offensive fires and reserving costlier missiles for defensive purposes or larger targets. Weaponised watercraft can bridge gaps in operational fires between joint effects such as naval gunfire support, tactical aviation, and ground-based artillery once it can be brought into action ashore. Under Project Land 4100 Phase 2 (land-based anti-ship system), early designs like the Bushmaster-mounted ‘Strikemaster’ will be capable of launching twin Kongsberg Naval Strike Missiles (NSMs). A mixed fleet of loitering munition canister launchers and NSMs would form the foundation of a formidable littoral strike network.

Sixth, integrating loitering munitions into the littoral combat team, as a combat program led by the Army, opens the door for further innovations and doctrinal development for land forces. For instance, while large unmanned expeditionary systems will continue to be operated by the Royal Australian Artillery and RAAF at higher altitudes and longer ranges, support companies of the future infantry battalions may generate an armed UAS platoon of smaller tactical munitions—the Hero-30 or -90, for example—designed to operate in direct support of the ground combat element. During an amphibious lodgement, echelons could hand off the targeting data and authorities of these systems depending on the status of the supporting-supported commander. Furthermore, while it takes decades to develop a new manned aircraft, loitering munitions and drones can evolve quickly, as their recent proliferation demonstrates. This is an advantage as threats and countermeasures interact quickly.

Figure 7. Concept art for the Israeli Sa’ar 4.5 Hetz-subclass missile boat employing Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI)’s Mini Harop Loitering Munition System from a 12-drone canister launcher (Source: IAI)[73]

Weaponising littoral manoeuvre watercraft with loitering munitions addresses two critical gaps in ADF capability and culture. It allows the joint force to fight in and from the littorals. The RAN’s focus is on large, blue-water vessels with advanced and expensive combat systems, unsuited for work in the littorals. The smallest vessel operated by the RAN is the Armidale-class patrol boat, which displaces 300 tons.[74] Its pending replacement capability under Project SEA 1180, the Arafura-class offshore patrol vessel, will be five times larger and will displace between 1,640 and 1,800 tons. The projected 13 Arafura-class vessels will cost around $4 billion.[75] The Army’s future watercraft need not be so exquisite and irreplaceable. Engagements within and from the littorals will, in part, protect and support these larger naval vessels, freeing their larger weapon systems for decisive surface combat.

Loitering munitions fill a lethality gap between cruise missiles and unmanned combat aerial vehicles. Many loitering munitions are relatively inexpensive, simple to operate, modular, and multi-role. They are capable of operation by dismounted soldiers, from armoured vehicles, or from watercraft, representing a logical investment for the Australian Army, a flexible force that operates across multiple domains. Armed watercraft could be used as a fire-support platform akin to the PT boats of the 1942–1945 South-West Pacific campaign, a precision-strike launchpad, an ISR and C2 node, a strategic deterrent, or merely an armed transport vessel capable of self-defence.

Conclusion

With the capability to conduct intra- and inter-theatre manoeuvre, deliver organic fire support, and distribute ground combat systems and landing force packages, the littoral manoeuvre capability represents a conceptual bridge between two competing ‘ways of war’. For the first time since the Second World War, the Australian Army will be capable of effectively operating in the complex archipelagic terrain of the region sometimes dismissed as an ‘air-sea gap’.

Loitering munitions present a viable option for arming the future fleet of watercraft, especially the small ‘flotilla’ vessels of the LMV-P program. Their combination of surveillance and precision strike affords operational flexibility and permissive, decentralised and cross-echelon fire-support methodologies. Along with other long-range precision strike capabilities acquired under Land 8113, the adoption of large loitering munitions will enable the Army to play a role in national defence at the strategic level of war. A prospective littoral operating concept may integrate communications networks with a wide range of munitions that fuse the strike system together at multiple echelons. This could see assets and fire control allocated down to the deployment of tactical-level littoral combat teams, which will be forward in the theatre, shaping the environment for larger follow-on close combat formations.

Weaponising watercraft with autonomous and semi-autonomous munitions, some capable of strategic strike, will represent a significant expansion of the Australian Army’s operational reach. Littoral warfare has a rich history in the Army and in the region, and it is essential that future watercraft are not overlooked for their warfighting potential. The littoral manoeuvre programs must deliver more than just ‘bigger whales’ and ‘faster cheetahs’.

While a full understanding of the impact of loitering munitions on future warfare will not be achieved without further operational experience, wargaming and testing, these systems will undoubtedly compel substantial changes in doctrine, platforms and force design. Weaponised watercraft will drive much of this change. A century hence, one should expect to see them among the War Memorial’s displays.

Acknowledgements

The author extends deep gratitude to Dr Michael Morris for his mentorship and guidance, to Dr Christopher Stowe and Dr Eric Shibuya for their leadership and insights, and to the Australian Army Research Centre for their support and review of this paper. All errors remain those of the author. This paper does not represent any official positions of the United States Marine Corps or the Australian Army.

About the Author

Ash Zimmerlie is an infantry officer in the Australian Army. His operational service includes Iraq, Afghanistan, Timor‑Leste, the South‑West Pacific, and domestic emergency response. He has fulfilled a range of regimental, training, representational and staff appointments. He holds a Bachelor of Arts and Master’s degrees in Military Studies, Operational Studies, and Strategy and Security. He is a graduate of the Australian Defence Force Academy, Royal Military College Duntroon, University of New South Wales, United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College (distinguished graduate), and United States Marine Corps School of Advanced Warfighting.

Endnotes

[1] This paper was written in 2022 and used the 2020 Defence Strategic Update as its reference point in responding to the Littoral Operating Concept. The 2023 Defence Strategic Review was released following this paper’s initial draft. Rewrites have incorporated the DSR, acknowledging that the central premise of Australia’s strategic shift has not fundamentally changed in the intervening three years. The DSU itself marked discontinuity in Australia’s strategic thinking. It outlined three new strategic objectives: (1) to shape Australia’s strategic environment; (2) to deter actions against Australia’s interests; and (3) to respond with credible military force when required. The DSR is simultaneously an expansion of these objectives and a narrowing of focus on the ways and means to achieve them. See Department of Defence, Defence Strategic Update 2020 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020), at: defence.gov.au/about/strategic-planning/2020-defence-strategic-update; and Australian Government, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2023), at: defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

[2] Defence Strategic Update, p. 6.

[3] Defence Strategic Review, p. 28.

[4] Michael Evans, The Tyranny of Dissonance: Australia’s Strategic Culture and Way of War 1901–2005, Study Paper no. 306 (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2005), pp. 33–35.

[5] Russell Parkin, A Capability of First Resort: Amphibious Operations and Australian Defence Policy, 1901–2001, Working Paper 117 (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2002), pp. 39–40.

[6] Evans, ‘The Tyranny of Dissonance’, p. 33.

[7] Paul Dibb, ‘Is Morrison’s Strategic Update the Defence of Australia Doctrine Reborn?’, The Strategist, 9 July 2020, at: aspistrategist.org.au/is-morrisons-strategic-update-the-defence-of-australia-doctrine-reborn.

[8] Evans, The Tyranny of Dissonance, p. 38.

[9] Peter Dean, ‘Amphibious Operations and the Evolution of Australian Defense Policy’, Naval War College Review 67, no. 4 (2014), pp. 33–34.

[10] Evans, The Tyranny of Dissonance, p. 55; Jeffrey Grey, A Military History of Australia (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 5.

[11] For the Australian official history on Operation POSTERN and the actions at Sattelberg, see David Dexter, Volume VI: The New Guinea Offensives. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Official History, Series 1—Army (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1968), pp. 326–560; for the US Army’s official history on Operation CARTWHEEL, see John Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific (Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1959).

[12] Samuel Eliot Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier: 22 July 1942 – 1 May 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 6 (Little, Brown & Company, 1950), pp. 257–258.

[13] Lachlan Grant, ‘Given a Second-Rate Job: Campaigns in Aitape-Wewak and New Britain, 1944–45’, in Peter Dean (ed), Australia 1944–1945: Victory in the Pacific (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 226; Gavin Long, Volume VII: The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Official History, Series 1—Army (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1963), pp. 242, 250–260, 269.

[14] Long, The Final Campaigns, pp. 344 (map), 377, 349–350.

[15] Eustace Keogh, The South West Pacific 1941–45 (Melbourne: Grayflower Productions, 1965), p. 453.

[16] Long, The Final Campaigns, p. 254.

[17] Michael Askey, By the Mark Five: A Definitive History of the Participation of Australian Water Transport Units in World War II (Turramurra: David Murray, 1998); Australian Army History Unit, ‘Moving Tanks by Water: A Short History of Australia’s Tank-Capable Amphibious Capability’, The Forge, 29 July 2019, at: theforge.defence.gov.au/publications/moving-tanks-water-short-history-australias-tank-capable-amphibious-capability.

[18] Christian Brose, The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare (New York: Hachette Books, 2022), pp. xxi, 228.

[19] Bob Moyse, ‘Winning Battles and Losing Wars: The Next Force Structure Review’, The Strategist, 19 September 2018, at: aspistrategist.org.au/winning-battles-and-losing-wars-the-next-force-structure-review.

[20] Ibid.

[21] ‘Independent Littoral Manoeuvre Vessel’, Austal Australia, at: austal.com/news/austal-australia-teams-raytheon-and-bmt-deliver-australian-independent-littoral-manoeuvre (accessed 21 November 2022).

[22] ‘Australian Maritime Alliance’s LMV-M Design Granted “structural approval in principle”’, 6 July 2022, Serco, at: serco.com/aspac/news/media-releases/2022/australian-maritime-alliances-lmv-m-design-granted-structural-approval-in-principle (accessed 21 November 2022).

[23] ‘CAPT Scott Corrigan watches as HMAS Balikpapan comes in on a beach near the West Timor border. Picture: ABPH Damian Pawlenko’, date unavailable, Defence website, at: images.defence.gov.au/oth991268-20.jpg.

[24] Jane Hardy, ‘Integrated Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific: Advancing the Australia-United States Alliance’, United States Studies Centre, 15 October 2021, at: ussc.edu.au/analysis/integrated-deterrence-in-the-indo-pacific-advancing-the-australia-united-states-alliance; United States Government Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States (Washington, DC: The White House, 2022), at: whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf.

[25] Peter Dean and Troy Lee Brown, ‘Littoral Warfare in the Indo-Pacific: Time to Start Thinking Differently about the US Marines in Australia’, Australian Army Land Power Forum, 22 April 2022, at: researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/littoral-warfare-indo-pacific. The modified Bushmaster, employing a ‘StrikeMaster’ launcher which fires anti-ship missiles and the National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS) short-range air defence—see Ian Bostock, ‘Australian Industry Mates Bushmaster Ute with Naval Strike Missile’, Defence Technology Review, no. 84 (2022): 26–30.

[26] Will Leben, ‘Beyond Joint Land Combat: How We Might Creatively Integrate Prospective Strike Capabilities’, Australian Army Journal 17, no 1 (2021): 70–72, at: researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/australian-army-journal-aaj/volume-17-number-1.

[27] Albert Palazzo, ‘Adding Bang to the Boat: A Call to Weaponise Land 8710’, Australian Army Land Power Forum, 1 December 2020, at: researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/adding-bang-boat-call-weaponise-land-8710.

[28] Fariborz Haghshenass, ‘Iran’s Asymmetrical Naval Warfare’ (Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2008), pp. 7–8; Milan Vego, Maritime Strategy and Sea Denial: Theory and Practice (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), pp. 119–120.

[29] Palazzo, ‘Adding Bang to the Boat’.

[30] Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1988 [London: Longmans: 1911]), pp. 121–122.

[31] Samuel Eliot Morison, New Guinea and the Marianas: March 1944 – August 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 8 (Little, Brown, 1953), pp. 57–58.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Bryan Cooper, The Battle of the Torpedo Boats (New York: Stein & Day, 1970), p. 170. For an example of a typical mission profile, see the account of a raid on a Japanese advance base in a New Britain estuary in William Breuer, Devil Boats: The PT War Against Japan (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1987), pp. 127–37. The Australian War Memorial offers footage of US Navy PT boats operating with RAAF Beaufort bombers in the Southwest Pacific Area, World War II: see ‘PT Boats At Sea’, Australian War Memorial, F02560, at: awm.gov.au/collection/F02560.

[34] Albert Palazzo, ‘Deterrence and Firepower: Land 8113 and the Australian Army’s Future (Part 1, Strategic Effect)’, Australian Army Land Power Forum, 16 July 2020, at: researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/deterrence-and-firepower-land-8113-and-australian-armys-future-part-1-strategic-effect; and ‘The Australian Army’s Coming Strategic Role: The Implications of the Precision Strike Revolution’, Australian Army Land Power Forum, 16 June 2022, at: researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/australian-armys-coming-strategic-role.

[35] A commander’s ‘deep area’ is defined as ‘the area that extends beyond subordinate unit boundaries out to the higher commander’s designated AO’ (from Allied Tactical Publication (ATP 3-94.2) Deep Operations, September 2016, p. 1-2, at: irp.fas.org/doddir/army/atp3-94-2.pdf); see

[36] Benjamin Gray, ‘Accelerating Land Based Fires’, The Cove, 15 August 2021, at: cove.army.gov.au/article/accelerating-land-based-fires.

[37] Defence Strategic Review, p. 59.

[38] The Royal Australian Air Force employs the MQ-4C Triton as a maritime patrol drone, complementing its P-8A Poseidon fleet; and the Navy and Army are due to deliver a maritime strike missile. See Jamie Freed, ‘Australia to Decide on Further Triton Maritime Drone Orders after Defence Review’, Reuters, 15 September 2022, at: reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/australia-decide-further-triton-maritime-drone-orders-after-defence-review-2022-09-15; Nigel Pittaway, ‘Land-Based Maritime Strike Option Leverages NMESIS’, The Australian, 30 May 2022, at: theaustralian.com.au/special-reports/landbased-maritime-strike-option-leverages-nmesis/news-story/f14759481f1b670cf06f78e1b6256a86; and Robin Hughes, ‘Australia Fast-Tracks NSM Block 1A for RAN Surface Fleet’, Janes, 11 April 2022, at: janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/australia-fast-tracks-nsm-block-1a-for-ran-surface-fleet.

[39] Mark Voskuijl, ‘Performance Analysis and Design of Loitering Munitions: A Comprehensive Technical Survey of Recent Developments’, Defence Technology 18, no. 3 (2022): 325.

[40] Brennan Deveraux, ‘Loitering Munitions in Ukraine and Beyond’, War on the Rocks, 22 April 2022, at: warontherocks.com/2022/04/loitering-munitions-in-ukraine-and-beyond.

[41] Shuo Wang, DongMei Shi, Yu Dong and Kai Huang, ‘Research on Distributed Task Allocation of Loitering Munition Swarm’, 2020 International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems (ISPDS) (ISPDS, 2020).

[42] J Noel Williams, ‘Killing Sanctuary: The Coming Era of Small, Smart, Pervasive Lethality’, War on the Rocks, 8 September 2017, at: warontherocks.com/2017/09/killing-sanctuary-the-coming-era-of-small-smart-pervasive-lethality.

[43] The US Marine Corps recently divested the M327 120 mm mortar, seeking a precision replacement under the Organic Precision Fires (OPF) project. The Russian military recently employed Iranian-designed Geran-2 loitering munitions in a series of airstrikes against Ukrainian cities and infrastructure. The Geran-2 is based on the Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industries Corporation (HESA) Shahed 136, an autonomous 2.5 m wide fixed-wing pusher-prop drone. It possesses a warhead between 30 and 50 kg. See Shawn Snow, ‘The Marine Corps Ditched the 120 mm Mortar, but This Might Replace It’, Marine Corps Times, 25 September 2018, at: marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2018/09/25/the-marine-corps-ditched-the-120-mm-mortar-but-this-might-replace-it; and Marc Champion, ‘What Are the Iranian Drones Russia Is Using in Ukraine?’, Bloomberg, 17 October 2022, at: bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-17/what-are-iranian-drones-russia-is-using-in-ukraine-quicktake.

[44] ‘Harop Loitering Munition System’, Israeli Aerospace Industries, at: iai.co.il/p/harop.

[45] Spencer Ackerman, ‘Tiny, Suicidal Drone/Missile Mashup Is Part of U.S.’ Afghanistan Arsenal’, Wired, 12 March 2013, at: wired.com/2013/03/switchblade-afghanistan; Tom O’Connor and Naveed Jamali, ‘“Suicide Drones” Linked to Iran Have Made Their Way to Yemen Rebels, Photos Suggest’, Newsweek, 27 September 2021, at: newsweek.com/suicide-drones-linked-iran-have-made-their-way-yemen-rebels-photos-suggest-1628204; ‘Russian Kamikaze Drone Captured on Video’, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 17 April 2021, at: https://rg.ru/2021/04/17/primenenie-rossijskogo-drona-kamikadze-pokazali-na-video.html. See also Roger McDermott, ‘Russian UAV Technology & Loitering Munitions’, Real Clear Defense, 6 May 2021, at: realcleardefense.com/articles/2021/05/06/russian_uav_technology_and_loitering_munitions_775980.html.

[46] John Antal, 7 Seconds to Die: A Military Analysis of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and the Future of Warfighting (Philadelphia: Casemate, 2022), pp. 45–60, 132.

[47] Deveraux, ‘Loitering Munitions in Ukraine and Beyond’.

[48] Kelsey Atherton, ‘Loitering Munitions Preview the Autonomous Future of Warfare’, Brookings Institution, 4 August 2021, at: brookings.edu/techstream/loitering-munitions-preview-the-autonomous-future-of-warfare.

[49] U.S. Department of Defense, ‘Fact Sheet on U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine’, 28 October 2022, at: media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/28/2003104896/-1/-1/1/ukraine-fact-sheet-oct-28.pdf; Ashley Roque, ‘Army Awaiting 100-plus Switchblade 600 Attack Drones’, Breaking Defense, 13 October 2023, at: breakingdefense.com/2023/10/army-awaiting-100-plus-switchblade-600-attack-drones.

[50] Jake Epstein, ‘Ukrainian Special Operations Forces Release Video Said to Show a Kamikaze Drone Taking Out a Russian Tank’, Business Insider, 24 May 2022, at: businessinsider.com/ukraine-video-taking-out-russian-tank-foreign-kamikaze-drone-war-2022-5.

[51] ‘Kamikaze Drones Successfully Used in Russia’s Special Operation in Ukraine—Defense Firm’, TASS Russian News Agency, 8 June 2022, at: tass.com/defense/1462311; Champion, ‘What Are the Iranian Drones Russia Is Using in Ukraine?’; ‘Kyiv Hit by Multiple Explosions after Russia Launches “Kamikaze” drones’, Guardian News, 17 October 2022, at: youtube.com/watch?v=HJbsB1liOKA.

[52] Tayfun Ozberk, ‘Loitering Munition Strikes Ukrainian Gunboat, a First in Naval Warfare’, Naval News, 6 November 2022, at: navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/11/loitering-munition-strikes-ukrainian-gunboat-a-first-in-naval-warfare; and ‘Analysis: Ukraine Strikes with Kamikaze USVs—Russian Bases Are Not Safe Anymore’, Naval News, 30 October 2022, at: navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/10/analysis-ukraine-strikes-with-kamikaze-usvs-russian-bases-are-not-safe-anymore.

[53] Atherton, ‘Loitering Munitions Preview the Autonomous Future of Warfare’.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Robin Hughes, ‘Hero-120 Loitering Munition Selected for USMC OPF-M System Requirement’, Janes, 23 June 2021, at: janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/hero-120-loitering-munition-selected-for-usmc-opf-m-system-requirement.

[56] ‘Hero-120 Profile’, UVision Smart Loitering Systems, at: uvisionuav.com/portfolio-view/hero-120 (accessed 24 November 2022).

[57] ‘Hero-30, Hero-120, and Hero-400EC photographed at the 2019 Association of the United States Army (AUSA) Annual Meeting & Exposition, Washington D.C., 2019’, Wikimedia Commons, 7 June 2021, at: w.wiki/9Wuo.

[58] ‘About Loitering Munitions’, UVision Smart Loitering Systems, at: uvisionuav.com/products/#.

[59] Hughes, ‘Hero-120 Loitering Munition Selected for USMC OPF-M System Requirement’.

[60] ‘Long Range Unmanned Surface Vessel Capabilities’, DVIDS, at: dvidshub.net/image/7765152/long-range-unmanned-surface-vessel-capabilities.

[61] There are many systems available in a rapidly expanding market. For a recent overview, see Dan Gettinger and Arthur Michel, Loitering Munitions in Focus (Center for the Study of the Drone, Bard College, 2017), at: dronecenter.bard.edu/files/2017/02/CSD-Loitering-Munitions.pdf.

[62] ‘At Sea: Multi-dimensional Coverage of the Naval Arena’, UVision Smart Loitering Systems, uvisionuav.com/solutions/hero-30-2-3/.

[63] The USMC defines ‘Stand-In Forces’ as ‘small but lethal, low signature, mobile, relatively simple to maintain and sustain forces designed to operate across the competition continuum within a contested area as the leading edge of a maritime defense-in-depth in order to intentionally disrupt the plans of a potential or actual adversary’. It adds: ‘Depending on the situation, stand-in forces are composed of elements from the Marine Corps, Navy, Coast Guard, special operations forces, interagency, and allies and partners.’ United States Department of the Navy, A Concept for Stand-In Forces (December 2021), p. 3, at: hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/142/Users/183/35/4535/211201_A%20Concept%20for%20Stand-In%20Forces.pdf.

[64] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (New York: Little, Brown & Company, 1963), pp. 272–274. For a description of the effects of these naval battles on Japanese strategy in the Southwest Pacific Area in 1943, see Hiroyuki Shindo, ‘The Japanese Army’s Search for a New South Pacific Strategy, 1943’, in Peter Dean (ed.), Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 68–87.

[65] Ridvan Bari Urcosta, ‘Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh’, Small Wars Journal, 23 October 2020, at: smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/drones-nagorno-karabakh.

[66] Sean Parrott, ‘Strike Platoon: Employment of Loitering Munitions in the Battalion Landing Team’, Small Wars Journal, 14 February 2022, at: smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/strike-platoon-employment-loitering-munitions-battalion-landing-team.

[67] Michael Stott, ‘Deadly New Russian Weapon Hides in Shipping Container’, Reuters, 26 April 2010, at: reuters.com/article/us-russia-weapon-idUSTRE63P2XB20100426.

[68] Palazzo, ‘The Australian Army’s Coming Strategic Role’.

[69] The United States Navy Expeditionary Combat Command (NECC) employs the CB90 as its Riverine Command Boat. See ‘HERO—Loitering Munitions’, Rheinmetall, at: rheinmetall-defence.com/en/rheinmetall_defence/systems_and_products/weapons_and_ammunition/loitering_munitions/index.php. ‘File:Stridsbåt 90.jpg’, Wikimedia Commons, at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stridsb%C3%A5t_90.jpg.

[70] HI Sutton, ‘Suspected Ukrainian Explosive Sea Drone Made From Recreational Watercraft Parts’, U.S. Naval Institute News, 11 October 2022, at: news.usni.org/2022/10/11/suspected-ukrainian-explosive-sea-drone-made-from-jet-ski-parts; Lara Jakes, ‘Sea Drone Attack on Russian Fleet Puts Focus on Expanded Ukrainian Arms’, New York Times, 31 October 2022, at: nytimes.com/2022/10/31/us/politics/russia-ukraine-ships-drones.html; Sam LaGrone, ‘Navy: Saudi Frigate Attacked by Unmanned Bomb Boat, Likely Iranian’, U.S. Naval Institute News, 20 February 2017, at: news.usni.org/2017/02/20/navy-saudi-frigate-attacked-unmanned-bomb-boat-likely-iranian.

[71] Williams, ‘Killing Sanctuary’.

[72] The Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey popularised this phrase in his 1966 book The Tyranny of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australia’s History (Melbourne: Sun Books, 1966).

[73] ‘Mini Harop’, Israeli Aerospace Industries, at: iai.co.il/p/mini-harop (accessed 22 November 2022).

[74] Stephen Saunders, Jane’s Fighting Ships 2012–2013 (Coulsdon: IHS Jane’s, 2012), p. 33.

[75] Julian Kerr, ‘Arafura Ahead of Schedule’, Australian Defence Magazine, 11 April 2019, at: australiandefence.com.au/defence/sea/arafura-ahead-of-schedule.