Littoral Operations for the Australian Army

Theory and Principles

Introduction

Fighting at, from and over the sea is one of the most challenging tasks a military force can undertake. It requires naval, land, air, space and, increasingly, cyber operations to work in concert. Such forces need to operate in one of the harshest environments on the planet, where the natural forces of sea and weather can prove as dangerous as any adversary. Logistics presents an entirely different set of problems than that of a purely terrestrial environment. Finally, the distances that are often involved in such operations complicate matters, from resupply through to the physical strain placed on ships and aircraft, along with the ever-increasing ease with which seaborne forces can be detected and potentially targeted. Nevertheless, such operations remain vital tasks for modern militaries, be they small-scale raids or major assaults. Whether we term these operations ‘amphibious’ or ‘littoral’ is an interesting conceptual question which will be addressed herein.

In the decade after the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, Australia’s strategic direction has refocused on the Indo-Pacific region. The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) and 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) directed that the Army optimise ‘for littoral manoeuvre operations by sea, land and air from Australia’.[1] The use of the term ‘littoral’ has caused angst and confusion, with many wondering if it is ‘amphibious’ by another name, and thus a distinction without a difference. This paper aims to inform the discussion around littoral warfare for the Army and the Australian Defence Force (ADF), and to inform the development of concepts and doctrine. The strategic emphasis on littoral manoeuvre will bring challenges, changes and opportunities, and will require ADF roles to evolve. Not everything will change. The ability to engage an enemy in close combat will remain Army’s core role. Optimising for littoral warfare will mean that Army can do this at a greater distance from Australia but, more importantly, will require the delivery of long-range strike against land and maritime targets. This capability will be a crucial component of Australia’s strategy of denial.

Combat operations from the sea are as old as seafaring and warfare. Appeals to ancient history for a storied antecedent are always fraught, but if done correctly demonstrate important lessons of the past. It may sound trite to talk of the Trojan War as an example of ‘maritime power projection’, but it was in fact (as much as it might have been an actual historical event) a collection of city-states imposing their will through warfare across the Aegean Sea. The history of Classical-era Greece (roughly 500–321 BCE) was often defined by maritime pursuits, including warfare on, across and from the sea.[2] The centuries that followed were littered with examples of maritime powers—from Venice through to Portugal, Spain, China, Japan, the Netherlands and Great Britain—influencing events across the seas with a combination of naval and land forces. More recent conflicts are no different: from the Russo-Japanese War through two world wars and into the 21st century, the ability to project power across the sea has remained an enduring concern of militaries around the globe. Technology has altered how it can be done, but the ‘why?’ has changed very little.

While amphibious operations have been spoken about, categorised and embedded into doctrine over the last century of military thought, the concept of littoral warfare as a discrete mission set is a relatively new one. The first problem starts with definitions, and the most common definition of littoral (in a military context) is quite generic: ‘the area in which shore-based forces can exert influence at sea, and forces at sea can exert influence ashore’.[3] On the surface, there is nothing wrong with this definition, but it does not really clarify the boundaries of the area. Instead, the boundaries are determined by technology and power projection capacity, a subjective measure that evades precise definition. Increases to weapon and sensor ranges have meant that what can be influenced from one domain to the next has grown. Indeed, one of the most defining features of the littoral is that it is a place where potentially all domains overlap: sea, land, air, space, and cyber. Perhaps the simplest way to think of the distinction is that all amphibious operations are ‘littoral’, but not all littoral operations are or will be amphibious. For example, a High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) firing anti-ship missiles (ASM) may be moved into its firing position by air or road. As such, it can generate effects in the littoral without having been involved in any sort of ‘amphibious’ operation. This is an important idea that will be explored further below.

This paper will provide background information and conceptual discussion around what littoral warfare might mean for the Australian Army in the near future. It discusses littoral operations through a land-power-centric lens.[4] Nevertheless, in the words of Milan Vego: ‘Littoral warfare requires the closest cooperation among the services, or “jointness”. It also requires close cooperation with forces of other nations.’[5] This paper is concerned with littoral operations from the standpoint of Australian land forces, but this is merely one perspective, not a claim to primacy. The paper will make the case for how land forces can be an invaluable asset in future operations conducted in what has been traditionally seen as a ‘naval’ theatre, complementing but not supplanting naval forces.

The first section of the paper will deal with Australia’s strategic situation. This will be followed by a discussion of theory, more specifically sea power theory. No land force operating in the littoral can be ignorant of the sea power theory that will govern its use in sea control, sea denial, or maritime power projection operations. The paper then provides a brief commentary on the maritime environment before discussing the all-important issue of definitions. This will lead into an analysis of how littoral operations might be classified into three different—but related—mission sets, in a similar vein to those of amphibious operations. These proposed mission sets are intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and targeting (ISRT); offensive operation/strike; and occupation/manoeuvre. Finally, a number of requirements for the successful application of littoral warfare will be explored and discussed, highlighting the key concepts that will govern land operations in the littoral. This covers everything from command and control through to logistics and technology.

This paper offers a basis for subsequent discussion. As highlighted above, the intent is to inform further development of Army littoral warfare and littoral concepts and, by extension, those of the ADF more broadly. There will be mentions of history and historical examples to highlight points of similarity—or difference. Nothing contained herein is prescriptive or doctrinaire. The main objective of this paper is not to ‘solve’ the question of littoral for the Australian Army but to provoke further discussion on the topic. Such inquiry is ‘a must’, as the ‘force in being’ must rapidly evolve to become comfortable conducting operations from—and surrounded by—the sea.

Australia’s Strategic Situation

Given the many and egregious misunderstandings that abound in the debate around Australia’s defence, it is necessary to contextualise this paper with reference to contemporary strategic—and physical—geography. The 2024 NDS outlined (in broad strokes) the strategic environment facing Australia in the Indo-Pacific.[6] Given Australia’s history, including countless Defence White Papers and other strategic analyses, this is nothing new. Australia is a large island continent that, since European settlement, has been reliant on the maritime domain for imports, exports and communication. The much misunderstood ‘tyranny of distance’ bedevils so many interpretations of Australia’s geography and defence. The idea that distance has always protected Australia is a fantasy. This is not a post hoc interpretation of history but a base acknowledgement of the initial rationale for the British establishing a colony in the faraway antipodes. Not just a land grab and place to stow convicts, Australia was in proximity to the Spanish, Dutch and French possessions within the Indo-Pacific and hence strategically invaluable for the ongoing global colonial and great power competition of the late 18th century and into the 19th.[7] Thus, it was not just commercial advantage but considerations of military positioning too that helped drive the expansion of outposts and ports around Australia such as Albany in 1826, Fremantle in 1828 and Port Essington in 1838—what Frank Broeze has called ‘Secondary Singapores’.[8] Moreover, by the 1840s Australia’s main trade link may have been with Great Britain, but a web of trade had been established throughout the Indo-Pacific, from Calcutta to Valparaiso. Therefore ‘Australia also firmly belonged to the maritime system of colonial and semi-colonial ports of Asia and the Pacific’.[9]

Indeed, advances in technology were seen as increasing the military threat to Australia as the 19th century progressed. The technology in question was steam power and the perceived threat was Russia. The Crimean War (1853–1856) sparked a panic over the Russian threat to Australian ports and gold-rush-fuelled shipping out of Australian ports, leading to the establishment of the Royal Navy’s Australia Station in 1859.[10] This new technology also changed the strategic calculus of sea power, as steam ships required regular access to ports and coaling stations. Again, in 1885 the mere rumour of Russian steamers at Cape of Good Hope and Singapore—thousands of miles from Australia—was enough to spark panic. As Frank Broeze points out, it was not just a direct threat to Australian territory but the threat to Australian shipping that was a prominent aspect of these Russia scares.[11] It is thus noteworthy to the modern strategist that in 1885, Melburnians perceived reports of Russian warships—some 6,000 miles and many weeks travel time away—as a distinct threat. While it was perhaps always an overstated threat in reality, the perception of it is an important consideration. It is therefore interesting that the myth is perpetuated, even today, that distance provides protection. In an era when Australia is still dependent on exports and imports by sea, and is potentially threatened by weapons with ranges of thousands of miles, it is hard to fathom how the ‘sea–air gap’ offers much in the way of protection now, when it has not done so in the entirety of Australia’s history.

It is often said that Australia has faced a tension between finding security from Asia, or from within Asia.[12] This should not be seen as a binary choice but as a spectrum. Australia has always had important trade and security connections throughout the region. Nevertheless, the critical trade which flows through the region is carried by merchant vessels that ordinarily sail at great distances from Australia’s shores and face the potential threat of hostile interdiction. For example, Australia is dependent on the importation of liquid fuel, a critical resource for the day-to-day survival of the nation. This refined fuel originates mostly from Asia, particularly Singapore, South Korea and Japan.[13] These countries, in turn, source their oil largely from Africa and the Middle East. The smaller amount of crude oil that is imported for local refining mostly comes from Asia as well, two of the top three originators being Malaysia and Vietnam.[14] Australia’s energy security is thus reliant on trade routes that span the entire Indo-Pacific region, including areas where Australia exercises only limited military influence. Further, the land areas of the region can be used by an adversary to threaten Australia more directly, less so for invasion and more so as a base from which to strike Australia and more closely interdict its trade.

For any nation with maritime interests, the projection of power across the seas is essential. Australia is of course an island nation reliant on the sea for imports, exports, and communication via underwater cables. These vital sea lines of communication stretch across the entire globe. Thus events far removed physically from Australia can have a dire effect on its economy and national security. An adversary need not get within 500 kilometres of mainland Australia to cause it irreparable harm. The spectre of continental invasion is scarcely credible when the cutting of Australia’s sea-lanes itself constitutes an existential threat. This observation should not be a revelation, as even a cursory understanding of Australian history over the last two centuries would reveal this basic fact. For example, the theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan recognised this threat at the dawn of the 20th century, noting that Australia would not find security by focusing only on local defence.[15] The infamous sea–air gap to Australia’s north is really a ‘sea–air–land gap’, whereby it is the land areas of the archipelagos to Australia’s north that require the Army’s attention.[16] In 1924 the Navy Board argued that the islands surrounding Australia could be used to threaten it; an adversary who occupied such territory would ‘constitute a menace until retaken … Australia would therefore be compelled, as soon as circumstances permitted, to despatch an overseas expedition to drive the enemy from the islands’.[17] The Japanese advance through the Pacific and up to Australia’s shores in 1941 would prove the validity of this analysis. Notable in this regard was the advice of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) to the Army that threats to Australia could originate from the surrounding littoral areas and that countering these threats would require a combined land–sea effort. For the ADF of the 21st century, it seems inevitable that future military operations will involve the projection of power at (and from) the sea, and that land forces will be integral to achieving such missions.

Suggestions that Australia can wholly rely on the use of ASM to defend itself are fantastical and cannot be taken seriously. Crediting nigh-on omnipotence and omnipresence to land-based anti-access / area denial (A2/AD) systems vastly oversimplifies the problem of targeting ships at sea.[18] This is not to downplay the threat of land-based anti-ship strike systems, but to point out that targeting defended, moving warships—spread across a vast sea space—is an extremely difficult task.[19] The vaunted combination of anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles and uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) has not been enough for the Houthis in Yemen to successfully strike warships patrolling the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Bab al-Mandab Strait, even with Russia provided targeting data.[20] These attacks are occurring in relatively confined waters, particularly compared to much of the sea space of the Pacific and Indian oceans. The successful sinking of the Russian Navy’s cruiser Moskva demonstrates that it can be done, and that successfully striking warships at sea requires the close cooperation of land, sea and air forces with precise targeting information. It also illustrates that ships operating alone with inadequate air defence systems are vulnerable—as they always have been.[21] This lesson needs to be heeded when discussing land-based contributions to future maritime operations.

Land-based maritime strike will be an important role for the Australia Army now and in the future, hence the need for a littoral approach to future warfighting. When deployed forward, land forces will be required to enable operations in the Indo-Pacific, whether by their presence, by their defensive capabilities, or by enabling offensive operations, either organically or in concert with the other services as part of the integrated force. The point here is that this outcome cannot be achieved from Australian shores alone. A maritime Maginot Line is not the way forward for the defence of Australia and its national interests.

Sea Power and Maritime Strategy

It is impossible to discuss the idea of amphibious or littoral warfare without putting it within the context of strategic theory. In this case, it is critical to understand sea power theory. An enduring problem is that sea power theory is often seen as a concept concerning only navies. This is not the case. Maritime, land and air forces all have critical roles to play in the conduct of sea power. This reality has existed for thousands of years, going back to the Ancient Greeks. The Ancient Greek word thalassokratia translates as ‘rule of/by the sea’, or more simply ‘sea power’.[22] Two of the best modern definitions of sea power make it clear that it is not the sole concern of navies:

Sea Power is that form of national strength which enables its possessor to send his armies and commerce across those stretches of sea and ocean which lie between his country or the countries of his allies, and those territories to which he needs access in war; and to prevent his enemy from doing the same.[23]

The capacity to influence the behaviour of other people or things by what one does at or from the sea.[24]

These are both simple yet revealing definitions. The first, by the Royal Navy’s Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, makes it clear that armies can be integral to effective sea power. The key phrase is ‘national strength’; he does not say ‘naval strength’. Naval, air, and indeed land forces form part of this strength and all have important roles in enabling—or denying—access across the seas. The second definition, by theorist Geoffrey Till, is less explicit but no less clear: sea power includes operations from the sea, meaning not just strikes but also the projection of land forces ashore. It is important to remember that there are maritime operations that indirectly affect events on land, and others that directly impact events ashore.

This is critical to understanding how littoral warfare fits within a wider strategy, especially for a nation so influenced by maritime considerations as Australia. The direction of the 2023 DSR and 2024 NDS reinforced that Australia must embrace a maritime approach to defence. Far from sidelining the Army, this has given the Army renewed prominence in the defence of Australia and its national interests.

There are three key sea power concepts that need to be understood when discussing littoral warfare: sea control, sea denial, and maritime power projection. These three concepts are deeply linked, and land forces have a role in their conduct. Specifically, the concepts govern how the Army will conduct littoral warfare and frame the strategic military objectives of such operations. To illustrate, an army’s littoral force will not only require sea control to manoeuvre but—once in place—may itself contribute to the continuance or extension of that sea control. Alternatively, it may contribute to sea denial operations. Most obviously, an army’s littoral force will be the object of an opponent’s maritime power projection efforts.

Sea Control

Sea control is critical to maritime operations, especially those that involve the movement of forces by sea. It is a term that, along with the older phrase ‘command of the sea’, implies totality. In reality, it is relative, limited both geographically and temporally. It is also contestable, and it is possible for no-one to have sea control. No definition is likely to satisfy everyone, and so for this paper the following will be used:

Sea control is a state by which a maritime force can conduct operations as desired at a certain time and in a certain place with no or minimal interruption by an opposing force. Simultaneously, the opposing force is unable to utilise the sea as they would wish in that particular space at that particular time. This includes air and subsurface space, and the electromagnetic spectrum.[25]

Sea control thus enables other maritime operations, especially littoral and amphibious operations. Importantly, it is not just necessary to enable friendly operations but also necessary to deny this control to an adversary. Attaining sea control is extremely difficult and requires active measures to maintain it. As the theorist Julian Corbett remarked, one side losing sea control does not necessarily mean the other side gains sea control by default.[26] In most cases, the sea will be contested and thus ‘uncontrolled’.

Based on such considerations, the concept of sea control in littoral operations is important for two primary reasons. As indicated above, the possession of sea control is a critical requirement in operations that involve the movement of land forces by sea. Such operations may involve the deployment of many large and vulnerable amphibious warfare ships in relatively static positions offshore. Even the transit of troop-carrying ships without sea control can be dangerous. For instance, on 7 November 1914 the Russian military caught and sank three Ottoman transport ships carrying troops, ammunition and equipment in the Black Sea, resulting in the loss of 3,000 soldiers and critical equipment.[27] Without control of the sea and air space in a littoral area of operations, it is all but impossible to transit by sea—let alone land on a hostile shore. Lack of sea (and air) control is why the Germans never attempted an invasion of Great Britain in 1940, and why the Allies spent so much time and effort to ensure their own sea control before crossing the English Channel in June 1944. In future littoral operations, sea control will be necessary at many points, especially in any lodgement phase or during major resupply operations. This is not to say operations cannot go ahead at all in the absence of sea control, but rather to emphasise that without it there is an enormous risk to friendly forces at sea.

When considering the concept of sea control and littoral operations, the second important consideration is how the land force itself can contribute. A land force equipped with maritime strike weapons and integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) can contribute to sea control alongside naval and air forces. Just as an air force or navy cannot unilaterally conduct land control operations, a land force will not be able to establish sea control without naval and air forces. But new land-based capabilities have widened the possibilities for land forces to threaten ships at sea at much greater ranges, and with greater lethality, than ever before. Given the combination of longer-range air defence systems, and modern capabilities that increase options to target ships and aircraft from the land, Army’s role in sea control and sea operations has increased significantly. This is in addition to the oft-overlooked fact that the forward operating bases from which strike and intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISRT) aircraft, and even naval ships, will operate, will need to be secured by land forces.

Sea Denial

Essentially, the concept of sea denial refers to the ability to prevent an adversary from using the sea as they would wish. It is often seen as a ‘weaker’ strategy than that of sea control since it does not allow for own-force use of the sea other than in defensive operations. While it is true that a military incapable of conducting sea control operations might instead rely on the conduct of denial operations to achieve its strategic objectives, it may also be the case that the conduct of sea denial operations is sufficient in response to a particular strategic threat. Indeed, nations may engage in sea denial operations against one another when control of the sea is contested.[28] Gaining but especially maintaining sea control is resource intensive and so a denial approach may be the most efficient one depending on the circumstances.

Traditionally, sea denial has involved the use of shorter-range, defensive weaponry, such as sea mines, torpedo boats, and fast attack craft equipped with guns and short-range missiles, as well as small conventional-powered submarines. In the era of prolific long-range strike, sea denial will often utilise longer-range offensive weapons, striking much further out to sea than has been possible in the past, including with hypersonic and ballistic missiles. Key to this increase in lethality has been advances in intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) technology that is able to provide targeting data to land-based forces. Modern sea denial operations will also involve fewer but more capable sea mines, far more sophisticated than previous generations of these weapons. Increasingly, uncrewed aerial and surface vessels are able to strike targets out at sea. While there is certainly a place for missile- and gun-armed fast attack craft in denial operations, uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) filled with explosives as ‘suicide’ craft now pose a serious threat to warships.

An example of an ongoing successful sea denial campaign is the Ukrainian Armed Forces campaign against the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet. The Russian fleet clearly overmatched the much smaller Ukrainian one, destroying its main fleet units at the outset of the war. This left the Ukrainian coast, including the strategically important city of Odesa, vulnerable to Russian naval forces conducting strikes or even amphibious operations. Nevertheless, Russian naval forces did not achieve sea control in the Black Sea. The Ukrainians were able to deny the Russian fleet this, using a combination of land-based strike systems such as ASM, UAS and, eventually, USVs. This sea denial campaign has included strikes against ships at sea, as well as vessels alongside in port.[29] At the same time, the Russian defences in the Black Sea are such that the Ukrainians cannot operate as they would like in the area. For example, they have been unable to position forces close enough to strike the strategically vital Kerch Strait Bridge with lasting effect, as they might if they were able to operate vessels closer to the Kerch Strait. In this sense, it is an almost textbook example of a contested sea, where both sides can deny each other the free use of the sea, but neither side is able to use the sea as they might wish.

Maritime Power Projection

Whereas sea control and sea denial are operations primarily focused at and towards the sea, the concept of maritime power projection (as the name suggests) is about projecting force from the sea to the land in order to directly affect events ashore. This can take the form of attacks from ships and ship-based aviation, and may also involve the projection of land forces ashore. It is a concept that spans the strategic level down to the tactical level of operations: everything from the island-hopping campaigns of the Pacific theatre in World War II down to small amphibious raids and naval gunfire harassing attacks against ports can be considered a form of maritime power projection.[30] Maritime power projection constitutes the ‘what is done from the sea’ component of sea power theory.

Land forces are an essential component in the achievement of maritime power projection. The ability to send and sustain a powerful land force across the sea has been definitive in many conflicts throughout history. Going back to Ancient Greece, land forces have often been critical in military efforts to secure key terrain. Equally, land forces are expected to be an important component of maritime power projection efforts in any future conflict, whether large scale or small scale, and including operations across a dispersed geographic span of the Indo-Pacific. What distinguishes modern littoral operations from those conducted in the past is that emerging technology now enables a land-based force—equipped for long-range strike—to position itself as a maritime power projection asset. This means maritime power projection will no longer be the sole purview of naval assets positioned at sea. This is an important conceptual point about how the littoral environment represents a confluence of geographies and joint effects. Increasingly, any of the three services can contribute to joint effects in this environment. This is an opportunity to be exploited, especially by the Army’s current and future force.

The Maritime Environment

The problems of operating in the littorals are exacerbated by the physical environment of the maritime realm. In the first instance, the sea itself is a disruptor, speeding or slowing the transit of ships depending on the weather. Wind and current can favour or impede a ship by up to six knots or more, adding or subtracting hours or days of transit time. Meanwhile, rough seas can have a substantial effect on people and their ability to operate, and something as trivial seeming as seasickness can materially affect operations at sea or forces landing ashore. For example, the Australian 18th Brigade spent 29 days at sea transiting from Australia to Morotai for staging before the Oboe II landings in 1945, degrading its physical fitness and training ability before a major operation.[31] While a modern amphibious warship is far more comfortable than a 1945-era landing ship tank, the fact remains that a ship is a poor place to enhance readiness for land operations. Then there is the harsh salt air and its effect on equipment, especially on anything that is not protected against it, as is the case with most army equipment. Waterproofing of vehicles and equipment is crucial, as is the proper loading of equipment in the order needed for disembarkation.[32] For a land force operating ashore for extended periods, this will be a serious consideration, even more so when transiting on open-decked transport vessels like landing craft (medium and heavy). This situation exacerbates the already difficult issue of logistics and sustainment for an expeditionary force.

The operating environment poses many challenges, both for maritime vessels and for land forces operating in the littoral, and even more so when targeting ships and aircraft out at sea. For ships and boats, operating in littoral waters can involve variable depths, strong tidal streams and currents, and numerous navigation hazards, from reefs through to small vessels. Atmospheric phenomena such as a super- and sub-refraction and ducting can aid or disrupt both communications and radar/electromagnetic sensing equipment.[33] Naturally a complicated electromagnetic environment, combined with the possibility of Global Positioning System jamming, means that navigation may well rely on traditional means. Accurate hydrographic data will be crucial, before and during such operations. This is in addition to all the issues of operating in the land environment.

In the case of Australia’s strategic environment, the physical geography of most concern is the Indo-Pacific region. It contains a wide variety of environments, perhaps none more challenging than the tropical jungles found around the region. Thick jungle canopies and coral reefs pose challenges to land and maritime forces operating here. Depending on the time of year, heavy rainfall, tropical storms, and cyclones or typhoons are potentially severe weather problems. Such weather conditions will affect all aspects of littoral operations—land, sea, air and electromagnetic. Technologies not designed for this environment will be severely degraded or will simply not work. For example, small UAS operating in a European climate will not be suitable in the rain and humidity of a Pacific island covered in jungle. They will be physically incapable of operating, and their sensors (designed to detect people in an open or European-type forest environment) will malfunction in these environments where the ambient temperature and humidity mimic those of a human body. This is not to say UAS will be useless, or that there is nothing to learn from their operations in current conflicts such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but to state that the operating environment is physically very different. The land environment and the maritime are both different to Ukraine and the Black Sea.

We should not only think in terms of offshore territory. The primary role of the ADF is to defend Australia, which itself has an enormous coastline with several thousand islands. The Australian coastline is approximately 59,000 kilometres, with a total of 8,222 islands.[34] Moreover, some 50 per cent of the Australian population reside within seven kilometres of the coast. Australia’s marine jurisdiction is the third largest in the world, with an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) covering 8.2 million square kilometres, plus an additional 2.5 million square kilometres of seabed jurisdiction beyond the limits of the EEZ under the continental shelf regime. This includes a series of strategically important islands in three different oceans. Heard Island and McDonald Islands are Australian territories in the Southern Ocean, and important research stations in the sub-Antarctic region. In the Pacific, Australia has the territories of Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island. Finally, and most significantly, there are Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean. These are not just Australian territories to be protected but potential assets. Christmas Island lies 500 nautical miles from the strategically important Sunda Strait, one of the few navigable passages through the Indonesian archipelago connecting the Indian to the Pacific Ocean. It is one of four significant straits to the north of Australia giving access to and from Asia.[35] The littoral environment applies not only to the Indo-Pacific region but also to much of Australia’s core geography that needs to be defended and is itself placed to influence the archipelagos surrounding Australia.

‘Littoral’ and Other Key Definitions

Definitions are important for setting the parameters of conceptual discussions. This is especially the case in the context of military thinking, where jargon predominates and doctrine has ingrained certain definitions for decades (if not centuries). Having said this, it is important that definitions do not become prescriptive, limiting the boundaries of thinking. Instead, there needs to be flexibility. On this basis, the definitions explored in this paper should be seen as a basis for exploring a concept, and not deterministic. There are three key definitions that need to be explored here, albeit only in brief: littoral, amphibious and archipelago.

Littoral

The very definition of littoral has become a contested one in recent times. As the Australian Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Simon Stuart, has defined it, in line with most modern definitions, the littoral comprises ‘the areas of the sea that influence the land and the areas of land that influence the sea’.[36] The US military definition divides the littoral into two key segments, seaward and landward.[37] Modern long-range weapons mean that most land areas are vulnerable to maritime forces, far beyond geographic areas that would have been considered littoral even 50 years ago.[38] While geography (both land and sea) is important, the word littoral also has a conceptual element. Specifically, in a military sense, ‘the littoral’ is an area where all the domains—sea, land, air, space and cyber—overlap. A more detailed description of the littoral is found in The Australian Army Contribution to the National Defence Strategy 2024:

It is a broad term that goes well-beyond just the physical environment. It includes the land, rivers, people, infrastructure, coastal waters, airspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum in these coastal regions … and even the space above them.

Littoral terrain dominates the Indo-Pacific region. Hundreds of millions of people live near the coasts, including 87% of Australians. The littoral connects us to our economic wellbeing: maritime trade arrives through coastal waters and shipping lanes, and goods flow through ports and airports in coastal areas. It is where the critical internet cables hit national shores, as the hubs of our digital world.

The lifeblood of the Indo-Pacific region, and of Australia, is in the littoral. This includes some of the most challenging jungle, mountain, riverine and urban terrain in the world.[39]

This description highlights two important elements that characterise the littoral domain: the physical terrain and the human terrain. Neither can be ignored or underestimated, especially in a region as diverse as the Indo-Pacific.[40] Here there are numerous geopolitical boundaries at sea and on land, including those that do not necessarily correspond with ethnic, religious or cultural boundaries. As seen below, these characteristics predominate in Australia’s ‘archipelagic’ operating area.

As indicated above, the physical terrain is formidable in its variety and the potential challenges posed to military operations. All three physical terrains of sea, land and air need to be considered, including rivers, estuaries and ports. The land environment in which the Australian Army will be expected to operate will consist of both heavy jungle and, potentially, low- to high-density urban areas. Much of the Indo-Pacific region has heavy rainfall and persistent humidity, a challenge and a hazard for both people and equipment, especially small UAS.

Human terrain in the littoral is often just as complex as the physical terrain. Before even reaching land, the offshore waters frequently play host to numerous civilian vessels of various makes and sizes, from ferries and merchant vessels down to all manner of small private craft and fishing boats. This cluttered human terrain will inevitably complicate military efforts to maintain situational awareness of the maritime surrounds. For example, targeting operations by land-based strike assets may be hampered if adversaries can conceal ISR assets among civilian vessels in these highly trafficked areas. Human terrain can also hinder the movement of friendly forces and the conduct of deception operations. The need to maintain situational awareness within offshore waters exists in parallel to requirements in the land domain that surrounds any littoral force, including nearby islands and offshore features that are non-contiguous with the force.

Amphibious

Amphibious operations have been well categorised over the last few decades, with a rich body of scholarship and doctrine. Briefly, an ‘amphibious force’ is defined as a naval and landing force, together with supporting forces that are trained, organised and equipped for amphibious operations. In the Australian context, an ‘amphibious operation’ is defined as a military operation launched from the sea by a naval and landing force embarked in ships or craft, with the principal purpose of projecting the landing force ashore tactically into an environment ranging from permissive to hostile.[41] The key aspect of something being ‘amphibious’ is the linear ship-to-shore—and reverse—dynamic of these operations.

Amphibious warfare and its attendant theory have developed over a long time. Typically, there are five categories of amphibious operations recognised in doctrine. Brief definitions based on Australian maritime doctrine are:

- Amphibious assault. Landing on a hostile or potentially hostile shore, including a build-up of combat power, aimed at having a decisive effect in a crisis situation or large-scale conflict.

- Amphibious raid. A swift incursion into hostile terrain, including the temporary occupation of an objective area, followed by a planned withdrawal.

- Amphibious withdrawal. The extraction of forces by sea from a hostile or potentially hostile shore. This may be done as part of a redistribution of forces to other areas or theatres.

- Amphibious demonstration. An amphibious operation conducted to deceive an adversary or potential adversary through a show of force. The aim is to induce the adversary into an unfavourable course of action.

- Amphibious support to other operations. Amphibious forces may conduct other operations such as humanitarian and disaster relief or stabilisation operations.[42]

For the purposes of this paper, there is no need to focus further on these concepts, as they have been defined, tested and revised over many years. It is productive, however, to consider how we might see ‘littoral’ as a new operational and strategic construct for modern land forces. The most salient point is that current operational and tactical concepts around amphibious warfare remain extant in any discussion of littoral operations now and in the foreseeable future. Some of the problem sets that the ADF may face will require one or more of such operations, independently or in concert with a more ‘littoral’ operation as discussed below. Indeed, many littoral operations will start as a more traditional amphibious one: a conventional amphibious landing in order to position a land-based strike element, for instance.

Archipelago

Key to understanding how operations in the littoral will be conducted is the practical, and legal, concept of an archipelago and archipelagic waters. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea defines an archipelago as:

A group of islands, including parts of islands, interconnecting waters and other natural features which are so closely interrelated that such islands, waters and other natural features form an intrinsic geographical entity, or which historically have been regarded as such.[43]

An archipelago is more than just a series of islands belonging to the same nation. Land and sea spaces are connected spaces, conduits for movement rather than barriers. Sea spaces are hives of activity—for transit, fishing and resource collection, and as spaces of cultural significance. This realisation is especially salient for Australia, which sits below the largest archipelagic nation on earth, Indonesia, and is surrounded by a host of others such as Papua New Guinea, Fiji and many other island nations.[44] It is a reminder of the complex physical and human terrain that defines much of the Indo-Pacific region, where the complexities of modern geopolitics play out across sea and land spaces in a terrestrially non-contiguous manner.

Archipelagos are, however, much more than just geography, as there is a distinct international legal regime in place that governs such waters. This regime regulates maritime areas and rights of passage through what are known as archipelagic states.[45] Considerations of archipelagic passage will be key in operating to the north of Australia. Operating in such an environment adds the perspective of international law to any sea, air and land domain considerations of a military nature.

Littoral Operations—a Proposed Classification Scheme

As with many things military related, classification is often a determining factor when discussing theory and concepts. While classification can have the effect of limiting thought, it does help refine ideas into a useful system. Therefore, the proposal here to introduce a classification scheme for littoral operations is not intended to confine further analysis. Instead, it provides the basis for further discussion, and even argument. What follows is one idea of how to conceptualise the operations which land forces will conduct in a littoral environment, separate to any traditional amphibious-type operations.

As the previous section illustrated, amphibious operations are well classified, but littoral operations have no such doctrinal breakdown. Specifically, there has been little discussion on what missions a land-based littoral force might conduct once it is positioned in an area of operations (AO). To address this deficit, what follows here is a proposal to classify three main missions for such a force:

- Intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and targeting. A land force tasked to provide ISR and to cue land-based strike elements and/or naval and air forces to own-force or allied units.

- Offensive operations/strike. A land force tasked to conduct operations against a land or a maritime target, as part of strategic strike or as a contribution to either sea control or sea denial operations. The force may conduct long-range or relatively short-range strike, including the use of sea mines.

- Occupation/manoeuvre. A land force positioned to occupy key terrain and/or littoral objectives such as a port, choke point, or maritime approach to a land feature. The purpose could be to control or deny the use of this terrain/infrastructure, including the use of IAMD. The force may need to manoeuvre from one land position to another to enable one of the other two operations, utilising the sea as an operational manoeuvre space.

To better understand the distinction between the land force’s role in littoral operations and its role in amphibious operations, it is instructive to draw a few comparisons.

- The land forces in an amphibious operation are more narrowly focused than those engaged in littoral operations. Amphibious forces are concerned with getting ashore and staying there before eventually moving inland to secure objectives. By contrast, the concerns of littoral forces will be much broader, requiring greater consideration of the other domains. While amphibious operations seek to project power ashore through land forces, littoral operations also involve projecting power from the land into the sea, and from one piece of land to another in the littoral/archipelagic environment.

- Unlike amphibious operations, which are conducted sequentially, the mission sets of littoral operations may also occur concurrently. For example, by its very nature an amphibious raid involves a withdrawal once the raid has been completed, thus an amphibious raid and an amphibious withdrawal are two separate missions. Equally, while a failed amphibious assault might result in a withdrawal, the assault and withdrawal are still two different mission sets with different planning considerations. In a similar vein, some littoral operations occur sequentially. For example, ISRT may be carried out before long-range strike. At other times, however, littoral missions will be conducted simultaneously. This could occur, for example, when the land force occupies key terrain (to deny it to an adversary) at the same time as a long-range strike mission is conducted (to support the denial mission).

- In essence, an amphibious operation is about projecting power ashore through land forces. Littoral is more than this: it is also about projecting power from the land into the sea, and from one piece of land to another in the littoral/archipelagic environment. While the main effort of the land force in an amphibious operation is focused principally inland, in a littoral operation the effort needs to be focused seawards. This is not to say a land-based littoral force can ignore events ashore. Specifically, such a force may need to repel an adversary by land, as well as to provide basic security and counter ISR. Nevertheless, the primary focus of the littoral force may change several times throughout a campaign or may be concurrent.

While not a unique characteristic of littoral campaigns, operations conducted in this environment might occur pre-conflict or after its outbreak. Before conflict, the military objective might be to support a strategy of denial through the establishment of a long-range strike or ISRT capability forward in the region, or the establishment of a land force to help occupy and defend an ally’s key terrain. After the outbreak of conflict, the continued conduct of littoral operations will require the movement and lodgement of land forces within a threat environment. To achieve this might require the lodgement of land forces ashore in a traditional amphibious operation.

Regardless of the nature of the operation, the precondition for the delivery of military effects is access to terrain. In this regard, any plan to deploy forces into and over foreign countries will depend upon the successful negotiation of access, basing and overflight rights. Such negotiations will occur at the diplomatic-political level and thus this topic lies outside the scope of this paper. This is in no way to trivialise the issue, and the course of many a conflict has been decided by such issues before the first shot is fired. This paper does not propose the conduct of littoral (or any other military) operations as some sort of Schlieffen Plan, to be executed without regard to political or diplomatic consequences.[46] No-one expects that operations will be conducted as per the Second World War, when fleets and armies moved through and occupied terrain in the archipelago as required, with no sovereign countries to consider. Modern littoral operations will obviously require access, basing and/or overflight. Regional engagement is a key priority for Australia, both in practice and conceptually.[47] The idea that this is some sort of missed planning consideration is simply not credible. The fact that Australia’s core operating region consists of a number of archipelagos that are sovereign nations has not escaped the ADF’s notice.

Regional engagement is something considered, planned and practised on a daily basis by all three services and the ADF as a whole, and has been for decades. It is a live and ever-evolving issue. The relevance of sovereignty to military operations is aptly demonstrated by the recently signed defence treaty between Australia and Papua New Guinea. This diplomatic effort will see greatly strengthened defence ties between the two nations.[48] It is whole-of-government efforts such as this, to which Defence contributes daily, that create the operational circumstances within which the ADF can prepare for future conflict. The key point here is that littoral operations might come on either side of the conflict line and across a spectrum, from competition to conflict. There is little point in having a littoral operating concept if the requisite access, basing or overflight rights are not in place when and where needed. The ADF is well attuned to this fact.[49]

However, on the other side of this, to be useful at all, a concept of operations must exist and be understood so that it is in place to execute if and when required. It speaks to the age-old adage that plans are useless but planning is everything. The concepts around littoral warfare are no different to those of sea, land or air power theory, on which many extant military plans are developed. Access, basing and overflight are key enablers to all military operations, not just those in the littoral.

Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance and Targeting

The lowest-signature and smallest-footprint mission for a land-based littoral force is ISRT. When considering ISRT missions, the most immediate image that comes to mind is that of the Coastwatchers of World War II, reporting on Japanese movements around the Pacific theatre and providing critical information to Allied forces. In a modern context, such a force would require a suite of surveillance tools, especially for the purpose of monitoring the electromagnetic spectrum and intercepting communications. The force itself would need to be both low signature and mobile, by land and sea. In all likelihood, such a force would be dispersed across several locations, to maximise the area which they could cover with their sensors.

This ISRT mission set will be of critical importance to the success of future littoral operations, providing surveillance and targeting data in any or all domains. This information will be invaluable not only for the littoral force itself but for informing the integrated force more broadly. Using land forces, naval and air force units could be provided with a much greater level of ISRT data than would otherwise be available. Not to be overlooked, any land-based littoral force will need accurate hydrographic data, not just in the traditional pre-landing operations phase of an amphibious lodgement but also throughout any operation where they need to move by sea. Such intra-theatre movements would require an organic hydrographic and geospatial capability. Importantly, hydrographic data will be required for all littoral operations, across the entire spectrum of peace, competition and conflict. For example, a landing operation conducted as part of a humanitarian aid / disaster relief operation will need just as much hydrographic survey data as an amphibious assault.

Special operations forces will be particularly adept at delivering the ISRT mission set. Such missions might be conducted to support the deployment of a larger follow-on body, or might constitute discrete missions in and of themselves. An example is the ISRT missions conducted by the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) operations in Afghanistan in 2001–2002. Deployed over three separate rotations, the almost entirely self-sufficient task force would deploy patrols for weeks at a time, tasked with long-range reconnaissance throughout the southern, western, eastern and north-eastern regions of the country. They were an invaluable presence in areas that had not been visited by any coalition forces to date, providing US and coalition partners with vital ISR data. In the case of Operation Anaconda, SASR patrols were crucial to the targeting of enemy forces throughout the two-week battle.[50]

Turning back to the context of littoral operations, any land-based force will need (as a minimum) ISR capabilities within the immediate AO and in all domains. The situational awareness requirements of such a land force will be significant as it will need to integrate water spaces as well as the land and air domains. Equally, such a land force could provide key intelligence inputs to inform the common operating picture of the deployed force more broadly, especially the water areas of the littorals that might otherwise be difficult for naval forces to keep under surveillance. Thus, a land-based littoral force can contribute a number of sensors into a common operating picture and, eventually, into a kill chain.

Offensive Operations/Strike

As explored above, one of the characteristics that make the littoral such a complex environment is the proliferation of land areas in a space otherwise dominated by sea. This creates the potential for multiple threat vectors from land-based forces, especially in conjunction with sea and air forces. There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages in a land-based long-range strike force, but overall the basing of strike assets in the land areas of the littoral will be of great utility to conducting sea control and sea denial operations.

Advantages of this approach include the potential for robust logistics and thus deep magazine depth, as well as concealment and the immutable feature of land as ‘unsinkable’. Achievement of this military edge relies on two primary factors: proximity to the national support base, and the provision of allied support in the forward staging area. Defending Australia’s northern approaches will benefit greatly from being able to draw on the national support base, provided the relevant enabling infrastructure is in place. The further one moves away from Australia, however, the more complicated the supply chain becomes, especially if supplies need to move through an adversary’s weapon engagement zone (WEZ). An example of this challenge arises in efforts to rearm at sea vertical launch system cells, which are the primary weapons system of modern warships. By contrast, systems such as the HIMARS are easier to reload in the field.[51] Land-based assets can also be more difficult for an adversary to target. This is because they can be more readily concealed through dispersion or camouflage, or their identity confused by the use of decoys.

While an island or land feature might be ‘unsinkable’ it is also, of course, immobile. The achievement of organic mobility for long-range strike assets is thus key to their preservation—mobility both by sea and by land, and by air if possible. The latter will be far more difficult in a contested environment or for a force maintaining a low signature, but the advent of autonomous resupply systems could assist in certain situations. The greatest challenge will be logistics. This issue is especially acute given the sensitive nature of long-range munitions such as the precision strike missile. Moreover, dozens of missiles will be required for an effective salvo against enemy targets, especially warships. Once again, timely and accurate targeting data is critical to operational success.

It is worth noting that a land-based littoral force could also enable defensive sea mining, a capability introduced into the ADF with the 2024 Integrated Investment Program.[52] Sea mines are a low-cost but highly effective weapon, able to sow doubt into the minds of an adversary even before the outbreak of a conflict. Even the threat of deploying this weapon can be an effective deterrence measure. Sea mines are also an excellent weapon for a strategy of denial. Aside from being positioned to deploy these mines, more important would be a land force’s ability to protect a minefield with land-based strike elements. For example, the Cold War NATO defence of the Baltic approaches relied heavily on naval mining to close choke points and defend vulnerable beaches from Warsaw Pact amphibious landings. However, an undefended minefield can be cleared and so, in the Baltic example, the Danish planned a series of land-based defences to protect the minefields by threatening any mine warfare units sent to clear the fields. This was done initially with artillery batteries (fixed or mobile) and then in the 1980s by mobile Harpoon ASM batteries.[53] An uncontrolled minefield can certainly interrupt and slow down an enemy’s plan, but a controlled field would pose a far more difficult defensive barrier to overcome.

Occupation/Manoeuvre

This third mission is the hardest to define, and easy categorisation is elusive. It is a task that spans competition and conflict, in either permissive or contested environments. Occupation/manoeuvre is a mission set that occurs post-lodgement—that is, once the force is ashore. It may be instigated through a traditional amphibious landing or assault which then transitions to a littoral focus. In a future contested environment, it is likely that an amphibious task group (ATG) may only have a limited window of access to land the required force. This narrow access window might be limited due to the requirement to penetrate an enemy WEZ, or it might be because the naval assets of the ATG (especially escort ships) are needed elsewhere. In either case, the initial amphibious lodgement will need to transition to something that resembles the Guadalcanal campaign of 1942–1943, where the initial US landings had limited support from naval forces as the sea and air spaces around the island were hotly contested for months post-lodgement.[54] In this type of scenario, a land force will require organic movement and lift assets. This will be especially crucial in a contested environment and inside a WEZ where, as the war in Ukraine has demonstrated, dispersion will be critical to a force surviving for any length of time.

For a land force operating in the littorals, the sea will need to become an operational manoeuvre space. With organic movement assets, a littoral force can utilise inshore waters and rivers for movement and resupply. However, more than just being necessary for communications and logistics, this movement capability will be required to enable the conduct of the other two mission sets, ISRT and offensive operations/strike. Forces positioned for ISRT may need to move in order to more effectively conduct their task. Fires assets will need to be positioned appropriately for targeting. High-value assets will also need sufficient mobility to survive.

The occupation of key terrain will itself be an important task for a littoral force, whether to control a vital piece of infrastructure or population centre, or to position enabling long-range strike for sea control or sea denial. In such a scenario, an amphibious landing (or raid) may need to be staged—not from the sea but from the land. Precedents for this include US Army operations in Sicily in 1943 along the north coast, and the United States Marine Corps (USMC) landing on Tinian in 1944. Both operations were launched from the neighbouring island of Saipan, itself previously taken in an amphibious assault.[55] In the Sicily example, these reinforced battalion-size landings were planned and executed in a matter of a few days. Beyond the initial insertion of troops, logistics resupply from the water was vital to the campaign’s continued success. This was due to the difficulties posed to land-based resupply by the rough interior terrain of Sicily and insufficient transport infrastructure. Australia too has experience of these types of operations, with several beach-to-beach landings conducted in Borneo during the various Oboe operations.[56] For contemporary operations, it will be critical to view water space as not just a barrier but also a potential operational and tactical manoeuvre space.

Examples such as these demonstrate the differences between amphibious and littoral operations. In traditional amphibious operations, land forces proceed from a sea-based force—such as an ATG—lodging ashore, building up a force and moving inland to secure objectives. Support is provided by the ships afloat, both logistics and fires support. Here, there is an ongoing tether between land force and naval force until the operation is complete, or until the forces are self-sufficient enough that an ATG is no longer required, the force instead being maintained via normal shipping through a captured port. By contrast to amphibious operations, in a littoral example the tether between the land force and the naval force does not endure. While a land force may be landed via a traditional amphibious landing or assault, the time on station for the ATG is limited by exposure to a WEZ, or the requirement for naval assets to be distributed elsewhere. Following the initial insertion, the land force leaves behind any organic naval assets, such as landing craft medium and/or heavy, that support troop movement. From here, the land force’s objective is to protect key terrain and contribute to sea control / sea denial operations. The land force will disperse throughout an archipelago, without an ATG, occupying and protecting key land terrain. It will conduct ISRT in several small, dispersed locations. It will be equipped with long-range strike assets that can contribute to local sea control or sea denial, or conduct strategic strike operations into adjacent land areas. Such a land force will require outside logistics support, most likely passing through or into a WEZ. The force’s ability to conduct local sea denial operations—and to defend its position by land—is critical to operational success. Such forces cannot be spread too thin, lest they become vulnerable in the same way as the ‘Bird Forces’ of 1942 were left unsupported and with insufficient organic capability to defeat the attacking Japanese forces.

Outcomes

It is all well and good to have a set classification scheme for littoral mission sets, but to have any purpose these missions need to fit within a strategy. At their core, littoral operations conducted by the Australian Army will aim to contest or contribute to sea control or sea denial efforts, or to project power in and from the maritime space. These are effects generated in and from the littoral environment in support of the integrated force.

Sea Control and Denial

In a national strategy of denial, the most obvious task for land-based elements in a littoral environment is to help protect vital sea lines of communication and contribute to joint force efforts to achieve sea control or, most likely, sea denial.

An example of a layered sea control / sea denial approach can be seen in Soviet Cold War strategy in the Pacific in the 1980s. The Soviets implemented a strategy of sea control in the Sea of Okhotsk.[57] Essentially, this sea became a ballistic mission submarine (SSBN) pen, where the nuclear missile armed submarines could range the US mainland, protected by a screen of mines, submarines, surface combatants, and land-based naval aviation armed with long-range anti-ship cruise missiles.[58] The geography of the Sea of Okhotsk (with its one, albeit large, entrance) meant that the Soviet Navy could concentrate here with a layered defence, establishing control within the Sea of Okhotsk and a very large area of sea denial in the approaches.[59]

Obviously Australia does not possess—nor will it acquire—nuclear weapons, but the principle of layered defence is nevertheless a useful construct. Rather than protecting an SSBN pen, the ADF could help protect forward operating bases, which in turn protect the Australian mainland. Corresponding with these efforts is the need for sea control in the surrounding seas and sea lines of communication. Given the range of many modern weapons systems, Australia’s national security interests are best protected if effective denial is achieved far from our shores, holding adversaries at risk before they can target critical infrastructure in Australia. The Australian Army’s role in this would be clear: establishing a footprint in a strategically important positions or positions, using the littorals as a manoeuvre space, and deploying long-range strike and IAMD assets to extend a ‘bubble’ of sea denial in the region.

Force Projection

The ability to project land forces into the region is key to achieving Australia’s national security objectives. With the requisite access, basing and overflight, the Army can be a powerful unit of maritime power projection, seizing and holding terrain as required, not just in a traditional amphibious operation but as part of a wider contribution to littoral operations. Thus, a land force in the littoral can be the object of maritime power projection, as well as conducting maritime power projection itself. Land forces will be integral to Australia’s maritime strategy going forward.

Describing a Potential Littoral Operation

The preceding analysis has explored how the littoral and amphibious operations differ. It has proposed a new way of thinking about how land forces can operate in the littoral environment that characterises much of the Indo-Pacific region. This section builds on this analysis by laying out a generic sequence of events for a hypothetical littoral operation. It demonstrates that there is crossover between amphibious theory and skills and the emerging littoral mission set, but that at a certain point a future land-based operation in the region will move from being ‘amphibious’ to ‘littoral’ in nature.

Our proposed operation is broken down into four different phases with different characteristics.

- Phase 1—Shaping and pre-landing operations (amphibious-littoral)

- Phase 2—Lodgement: via amphibious assault/landing, sea and/or air lift (amphibious)

- Phase 3—Exploitation and control (amphibious-littoral)

- Phase 4—Sea control, sea denial, maritime power projection (littoral)

Phase 1—Shaping and Pre-landing Operations

Like any expeditionary operation, a littoral one will require shaping beforehand, most notably by obtaining the aforementioned requisite access, basing and overflight rights for military capabilities that are expected to operate within another nation’s borders. As highlighted earlier, creating the conditions for such agreements is an enduring line of effort from the Army and the wider ADF in maintaining strong contacts through the region through regular exercises and exchanges. Building and maintaining these good relationships is a key role and vital to the success of any future deployment.

The scope and nature of any pre-landing operations depends heavily on the manner of entry for a littoral force. This comes down to which side of the conflict line the deployment is made on. Deploying to an allied or partner nation before the outbreak of a conflict may take place over several weeks or even months, in a permissive environment using a combination of military and civilian lift. In such a situation, it might be possible to pre-position and/or cache equipment and supplies in forward areas, such as northern Australia or offshore Australian territories, in preparation for a potential deployment. Such an operation would be unlikely to need many of the traditional pre-landing operations such as beach survey and obstacle clearance.[60] On the other end of the spectrum, it may be that a littoral force needs to lodge somewhere in a non-permissive environment, in a traditional amphibious operation, and thus requires all of the standard pre-landing operations. In both cases, shaping and information operations will inevitably be required.

Phase 2—Lodgement

The lodgement phase of a littoral operation may look just like an amphibious operation, or it may differ entirely. How a force is lodged will depend on many considerations. The first of these factors is timing. For example, a land force might be positioned well before the outbreak of a conflict and built up slowly over time. This is the sort of regional ‘forward presence’ that scholars have mooted recently. It could involve the ADF being deployed forward into the region, on home soil such as Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Christmas Island, or even further forward in a place such as the Philippines.[61] In this scenario, the force might be deployed by sea and air lift, whether civilian or military, potentially in concert with another ally such as the United States.

After the outbreak of a conflict, lodgement into an AO will be very different. It may be necessary to stand up an ATG to conduct an amphibious landing, perhaps even an amphibious assault—although the latter would be done only under extreme circumstances and require significant assets. An ATG is a very vulnerable asset that has a large footprint and is relatively slow—and stationary at the point of disembarkation. This makes sending an ATG into a WEZ a risky proposition, and the more time spent in the WEZ the greater the risk. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that, in a future littoral operation, an ATG might remain in the AO only long enough to disembark forces before leaving. Further resupply and reinforcement would need to be conducted in lower-signature operations, perhaps only one or two ships at a time.

So while it may look like a conventional amphibious landing, a key difference will be the removal of the ATG—and thus afloat support—from follow-on operations post-landing. A historical antecedent to this is the US operations to take and hold the island of Guadalcanal in 1942–1943, when the sea and air space around the island was hotly contested by the Japanese forces. This made US aircraft carriers and transports very vulnerable. In response, the US carrier commander, Rear Admiral Jack Fletcher, declared that his carriers would only remain offshore for two days, increased to three after vigorous arguments from the landing force and USMC commander.[62] This example illustrates that the needs of the landing force must be balanced with the vulnerability of mission-critical transport and escort vessels.

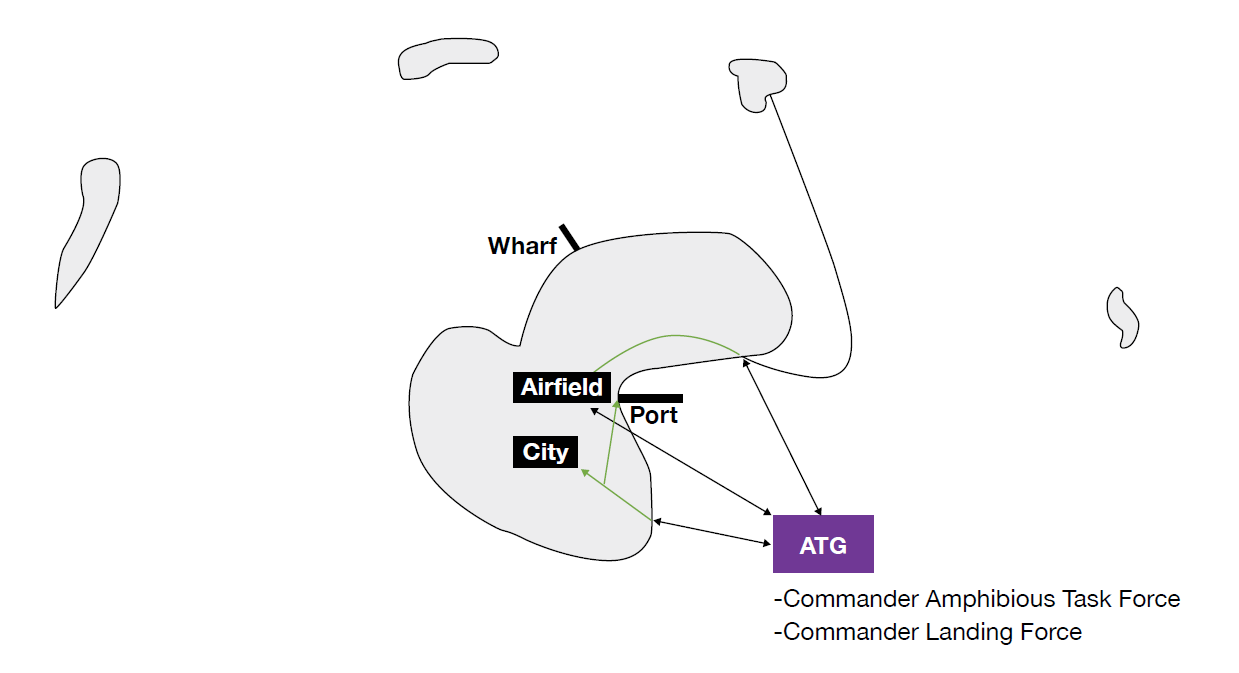

In essence, the lodgement phase of any future littoral operation is likely to look similar to those of the past, whether the operation is preceded by a force build-up phase, as with post-INTERFET Timor or Afghanistan, or constitutes a traditional amphibious operation. Either way, getting ashore in the future is unlikely to look different to how it does now, save the addition of new medium and large landing vessels. Therefore, it seems unnecessary to apply a ‘littoral’ lens to the issue of how future land forces will get ashore. Figure 1 provides a basic graphical representation of a generic amphibious operation. An ATG inserts a force ashore, by sea and/or air, and provides ongoing support during the operation. Sea/air forces established ashore are also tasked to conduct operations on nearby islands in a shore-to-shore movement.

Phase 3—Exploitation and Control

Once a force is ashore it needs to be secure in its position. For a littoral force this requirement will likely be of less concern if the force is operating from Australian territory or in an allied country. While a traditional amphibious landing requires exploitation and consolidation to move further inland, the focus is just that: inland. By contrast, a future littoral force will need to be more broadly focused. It will need to think about exploitation and control both inland and seaward, especially in the likely event that the ATG and supporting naval forces have departed the AO. The land force will also need to consider exploitation, consolidation and control in all domains, rather than being rigidly focused on its efforts to move inland.

In practice, this means there may be few or even no significant objectives inland to concern a littoral force. It may be that inland objectives are not traditional amphibious objectives such as securing population centres or large swathes of an island. The force may instead focus on securing advantageous positions for ISRT, long-range strike, and IAMD. This realisation goes to the heart of what will differentiate an amphibious from a littoral operation: a focus on the seaward spaces rather than inland. Manoeuvre operations—by land and sea—will seek to secure positions for these littoral mission sets. This is not to say there will not be a landward threat, but in all likelihood a littoral land force will position itself defensively in order to enable long-range operations. Aside from controlling sea and aerial ports of debarkation (SPODs/APODs), it may be that control over land areas is ephemeral, necessary only insofar as it enables other operations. In this regard, the Guadalcanal example is again instructive. Here, the primary role of the land force was to defend the airfield, which in turn was to be used as an asset to extend air and sea control around Solomon Islands.

Phase 4—Maritime Strategic Operations

As discussed earlier, the ultimate outcome of positioning a land force in the littoral is to occupy key terrain and contribute to sea control, sea denial, and maritime power projection—maritime strategic operations as discussed earlier in this paper. This is an emerging role for the Australian Army, and for most land forces around the globe. It is a role for which there is little if any Australian precedent and it is the role that most clearly demonstrates how littoral warfare will differ from amphibious warfare.

As explored above, it is possible that a land force may have been positioned in Australian or allied territory in a permissive land environment, pre-conflict, without the need for an ATG or any sort of ‘amphibious’ operation. Such a force will still need to manoeuvre in the littoral environment, for intra- and inter-theatre resupply, to manoeuvre strike assets, and for ISRT. Accordingly, such a force will need to operate out of ports and over beaches and it will require many of the core skills inherent in the successful conduct of amphibious operations.

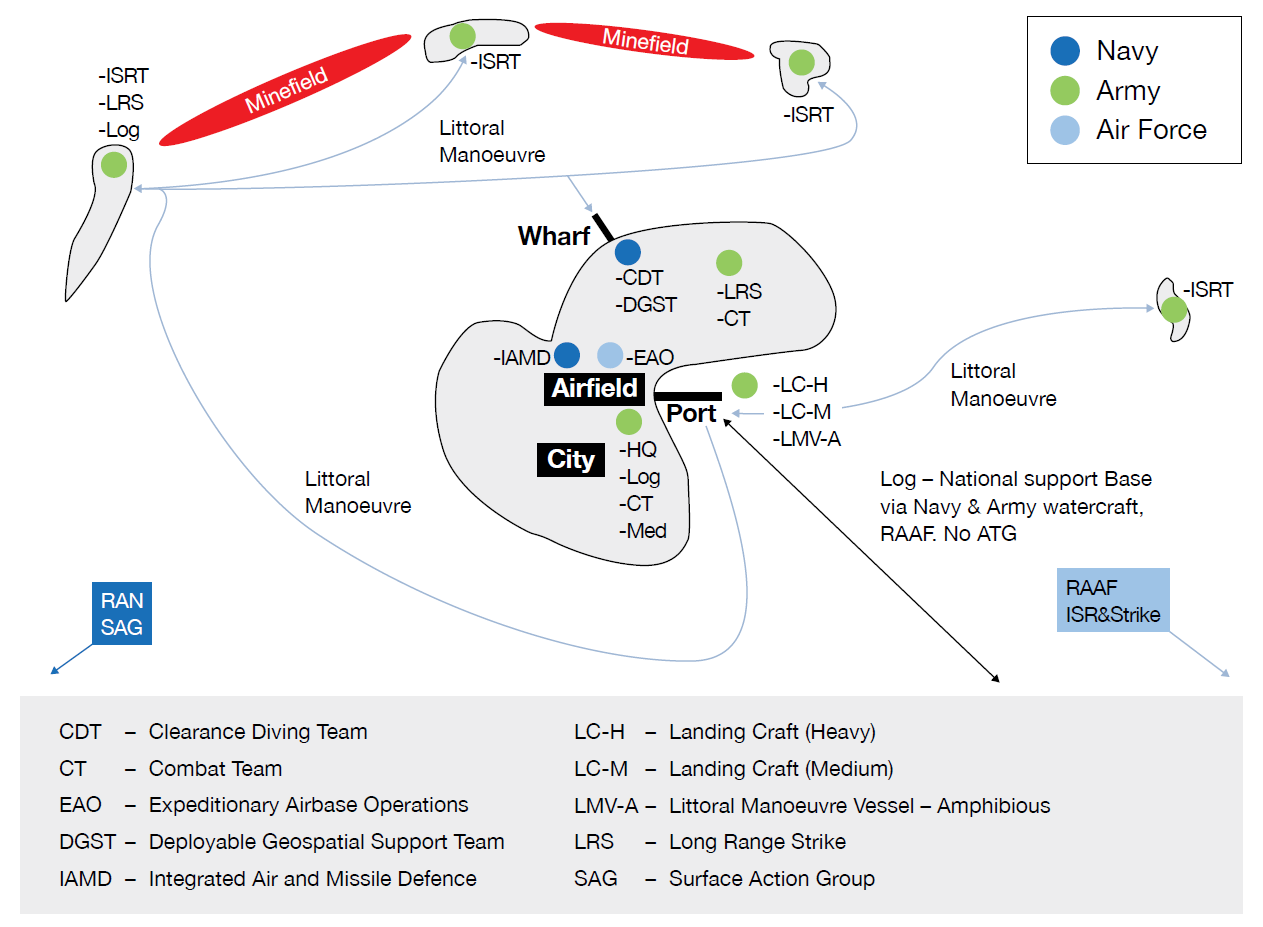

A post-lodgement littoral operation is shown in Figure 2. In this example, the littoral force might be operating out of Australian territory, or from a friendly nation with the requisite access, basing and overflight. It arrives in the AO before or after the outbreak of a conflict, in a slow build-up or in a traditional amphibious lodgement. Having established a footprint at the main APOD and SPODs, the land force establishes IAMD and long-range strike assets, protected by combat teams of infantry, infantry fighting vehicles, and armour as required. They are supported by engineers and logistics units, with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) establishing airbase operations. The RAN provides support in the form of clearance divers and geospatial survey capabilities to support littoral manoeuvre and logistics over the beach as required. This effort is supported by Army-operated landing craft heavy and medium, as well as amphibious vehicles. This allows the force to establish small footprints on outlying islands in the archipelago for ISRT, feeding information back to the land force and, in turn, to RAN and RAAF units positioned in support. Defensive naval minefields are established to channel enemy movement, overwatched by local strike assets.

This scenario demonstrates a littoral force conducting all three categories of littoral operations: ISRT, strike, and occupation and manoeuvre. In doing so, the force contributes to the broader strategic objective of sea denial, sea control, and maritime power projection. While not all littoral operations will be of this scale or complexity, the example illustrates what a high-tempo, maximum-effort littoral operation might look like.

Requirements for Modern Littoral Operations

Having developed a core mission set for littoral operations, and situating these operations with other military operations and wider strategy, it is necessary to explore some basic requirements for the conduct of modern littoral operations. The list offered in this section is not intended to be exhaustive; nor should it be revelatory. Many of the elements listed are common to any military operation, in any environment. The key objective here is to put these requirements into a littoral context.

Littoral operations are focused on three main outcomes: projecting power ashore with land forces and/or firepower; denying a land area to an enemy; and/or denying a maritime area to an enemy. This statement is qualified by the words ‘and/or’ because it may be the case that one, two or all of these outcomes are desired. Moreover, projecting power ashore may in fact occur from ships or from other land forces, and probably both. What makes the context ‘littoral’ is that those land forces are positioned firmly in the overlap of the five domains, equipped and directed to affect these domains. For example, it is easy to imagine forces being landed ashore from the sea in a traditional amphibious operation, and then having these forces use the sea as an operational manoeuvre space to position (as appropriate) for ISRT and/or strikes against land or maritime targets.