Finding Asymmetry During Mobilisation in the Australian Army

Abstract

The mobilisation of national economies, industries and armed forces for war has long been a complex problem. Mobilisation brings a range of issues that both government officials and military staffs must navigate to be successful; it is no easy task. As great power competition increases across the globe, and the likelihood of conflict in the region rises, the Australian Army should consider the ways in which it might find competitive asymmetry if it were to be mobilised in defence of Australia. This paper seeks to demonstrate that Army’s capacity to weather previous national mobilisation events has been supported by a body of trained personnel delivering ‘just in time’ mobilisation effects. As Army prepares for all future scenarios, it must acknowledge the depth, and latent skill, held within its ranks and within society that will support mobilisation efforts. Where once the Army called upon personnel with a mere 30 days’ training per year, it can now draw upon personnel with an average of 10 years’ experience. It is the depth and quality of professional training resident within Army’s workforce, and society, that will give Australia an asymmetric advantage over its adversaries during conflict.

Introduction

Why Talk about Mobilisation?

Source: Australian War Memorial, P01875.002

Since the conclusion of the Second World War, Australians have enjoyed the benefits of a long period of relative peace and associated improvements to their standard of living. However, change is afoot. Australia is now in a period of uncertainty. The mobilisation of large-scale land forces may be required to respond to security threats from within the Pacific region or further afield. Recent conflicts such as the Russo-Ukrainian War and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict only heighten global tensions. They also demonstrate clearly that large-scale combat operations are still a modern reality.

Despite an uncertain future, it is both important and necessary to understand how Australia has weathered similar events in the past. As Mark Twain wrote, ‘History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends’.[1] As has happened before, the global security landscape, and specifically the Pacific region, is facing major strategic realignment. Specifically, it is seeing trends such as military modernisation, technological disruption, and an increase in the risk of state-on-state conflict.[2] Australia’s primary operating environment is now at the centre of great strategic competition between the major regional powers: the United States and China. Recognising this shift, the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) noted that ‘for the first time in 80 years … the prospect of major conflict in the region … directly threatens our national interest’.[3] This assertion highlights the necessity for military professionals, government officials, and academics to understand the implications of a major conflict in our region.

The potential for major conflict in our region, and the uncertainties inherent in the current global security landscape, has parallels to the security climate in the pre-Second World War era of the 1930s. Those parallels are characterised by a web of international alliances and partnerships where great power competition steadily increased between authoritarian and liberal democratic states. These similarities should give Army reason for pause and encourage it to engage in robust discussions and debate on mobilisation. It is critical that Army understands how it has mobilised in the past, how it could be mobilised in the future, and what asymmetric advantages it could bring to bear when called upon to do so. To that end, this paper explores Australia’s mobilisation history, the concepts of tacit and explicit knowledge, and Army’s greatest asset: its people and their leadership.

This paper asserts that Army can establish asymmetric advantage during mobilisation through the depth of knowledge, skills and leadership that it retains within its senior soldiers and officers. Mobilisation is a complex endeavour, and this paper reveals many weaknesses in how Army has met this challenge in the past. While this paper focuses on people, equally equipment and its availability is a critical component of any debate around Army mobilisation. To avoid organisational shock, complex problems require early thought and attention. The debate needs to begin now, before strategic circumstances compel Army to deliver capability solutions in response to a clear and present threat to Australia’s national interests.

Setting the Context

In its relatively short history as a Western nation, Australia has mobilised land power in pursuit of national objectives on average every 10 to15 years: Second Boer War 1899–1902, First World War 1914–1918, Second World War 1939–1945, Korea 1950–1953, Vietnam 1962–1972, East Timor 1999–2000, Iraq War 2003–2009, Afghanistan 2001–2021, National Bushfire Emergency 2019, and COVID-19. On two of these occasions, the nation mobilised every instrument of national power to achieve its objectives—those being the First World War and the Second World War. These two periods are of particular significance to this analysis because they offer a lens through which to understand how Australia previously entered national mobilisation, how it dealt with shortfalls in leadership and training, and how it has successfully produced land forces for conflict.

To explain the different types of mobilisation that Army may be called upon to effect, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has generated mobilisation categories. At the time of writing, these categories are described in the Australian Defence Doctrine Publication (ADDP) 00.2—Preparedness and Mobilisation, 2013, as follows:

- Stage One—Selective Mobilisation (e.g. an engineer squadron sent to support a flood response

- Stage Two—Partial Mobilisation (e.g. Australia’s 1999 commitment to Timor-Leste)

- Stage Three—Defence Mobilisation (e.g. the whole-of-ADF response to COVID-19 or Bushfire Assist 19, which included the call-out of the Army Reserve)

- Stage Four—National Mobilisation (e.g. Australia’s whole-of-government response to the First World War and the Second World War).

Based on these categories, it is apparent that mobilisation is a term used to describe a broad range of scenarios; its nature is entirely dependent upon the situation and its associated context. Many nations around the world invest in relatively small professional armies, acknowledging that they can achieve only limited peacetime objectives within the first three stages of mobilisation. However, while a focus on domestic security and peacekeeping may be understandable from the national economic perspective of some countries, Australia’s strategic settings demand that it must also be prepared to mobilise its entire national power base to generate forces for either aggressive or defensive purposes.

To support the achievement of contemporary Australian national security objectives, the Australian Army can benefit considerably from reviewing its contribution to the only previous instances of Stage Four—National Mobilisation: the First World War and the Second World War. The stages explained above are useful to bound the scale of mobilisation and limit discussion on the topic. However, one glaring omission from the definitions is that they only provide the start point for mobilisation. None of them explain when mobilisation stops or is complete. As stated at the start of this paper, mobilisation is a complex process which raises a multitude of questions that require answers, and many of those are not forthcoming. Given its complexities and the broad responsibilities associated with mobilisation, nations around the world typically choose to maintain smaller professional armies that can achieve limited peacetime objectives within the first three stages of mobilisation.

The First and Second World Wars were periods when Australia needed to escalate its mobilisation level to Stage Four–National Mobilisation in response to external threats. In both cases, and in response to an external threat, the Australian Government declared war in support of its closest ally at the time—Great Britain. These declarations triggered Australian military mobilisation en masse. Examining this historical experience through a contemporary lens may assist Army to establish asymmetric advantage in the event that it is required to mobilise again.

Source: Australian War Memorial, H11604.

Historical Review

Reconciling Terminology—The Australian Army 1901–1946

During the research for this paper, one issue rose above others as needing clarification at the commencement of this historical review. That issue is the naming conventions used to describe the Army. The creation of new organisations and structures invariably leads to periods of change as people attempt to settle upon a common lexicon that accurately reflects a certain image. The initial history of the Australian Army is no different, and from Federation in 1901 to demobilisation following the Second World War in 1946, the Army underwent five major changes to its overarching titles that were used to describe force structure. This short portion of the historical review is aimed at providing the reader with context for the titles and terms used between these periods to describe what is now known as the Australian Army.

The terms used to describe the Army during this period can be particularly confusing because acronyms, while remaining the same, denote different meanings. For example, between 1901 and 1915 ‘Commonwealth Military Forces’ (CMF) describes the entire Army. However, from 1916 to 1929 ‘CMF’ refers to the Citizen Military Forces, who were part-time soldiers and officers. These subtle changes in terminology can translate to major differences in meaning and in the purposes of the forces being described. As a result, it is crucial to highlight early in this work when these changes occur in time and how the components of the Army are referred to.

Prior to Federation the six colonies of New South Wales, Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Queensland were independently responsible for their own security. As a result, after Federation there remained a mix of permanent, part-time and volunteer units across the six former colonies. The Australian War Memorial (AWM) provides the most succinct and clear description of the periodic titles and organisational terms used between 1901 and 1946. Listed below is an excerpt from the AWM providing an overview of each organisation’s overarching title, associated timeline and force structure.[4] For simplicity, the list from the AWM has been modified to present the structural names for part-time and volunteer, permanent, and expeditionary forces respectively.

1901–1915: Commonwealth Military Forces (CMF)

Citizens Forces

Permanent Forces

Australian Imperial Force (AIF—from 1914)

1916–1929: Australian Military Forces (AMF)

Citizen Military Forces (CMF)

Permanent Military Forces (PMF)

Australian Imperial Force (AIF—until 1921)

1930–1939: Australian Military Forces (AMF)

Militia (known unofficially as the Australian Militia Forces (AMF) or the CMF)

Permanent Military Forces (PMF)

1939–1942: Australian Military Forces (AMF)

Militia (known unofficially as the AMP (often corrupted to Australian Militia Forces))

Permanent Military Forces (PMF)

Australian Imperial Force (AIF)

1943–1946: Australian Military Forces (AMF)

Citizen Military Forces (CMF)

Permanent Military Forces (PMF)

Australian Imperial Force (AIF)

The above list shows the variations within naming conventions used throughout this early period of the Army. As this paper progresses, it will reinforce when naming conventions change, to support the reader in anchoring themselves to the correct period and associated terminology.

Kicking It into Gear—First World War Mobilisation

The Commonwealth of Australia had only been in existence for 13 years when the drums of war beat out in August 1914. Despite Australia’s fledging statehood, the country successfully mobilised the Army and the national economy to support the war effort. The 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF), comprising 20,000 men, was mobilised in three weeks and then dispatched within three months.

This major achievement was supported by several contributing factors. In succession, Australia’s first General Officer Commanding, Major-General Edward Hutton, commenced training reforms in 1902 to address the wide variations in military knowledge, organisation and efficiency of the nation’s citizen soldiers.[5] The Australian Government had introduced compulsory military training in 1909 that would provide access to trained personnel of varying standards from 1912. Lord Horatio Kitchener’s visit to Australia in 1910 initiated major structural reforms and re-energised the professionalisation of officer training. There was also a timely review of how to support an offshore expedition, which was directed by the Minister of Defence between 1910 and 1913.[6] These elements contributed to what could be viewed as the ‘just in time—with just enough’ mobilisation of the Army. These events are worthy of deeper analysis.

Organisational Reform. Australia’s first General Officer Commanding was, perhaps not surprisingly, a British officer who had spent time commanding colonial forces in New South Wales, during the South African War and in Canada. Hutton assumed command of the Commonwealth Military Forces (CMF) on 29 January 1902 and commenced the reforms he deemed necessary to craft a coherent defence organisation by amalgamating the forces of the six pre-Federation colonies and determining a strategy for their use.[7] Hutton’s influence on the CMF cannot be understated. During his inspections of six states and three military districts, he found organisations where training had not progressed past elementary levels of drill for ceremonial parades. He also determined that the delivery of advanced training was nearly impossible due to training camps only running for three to four days.[8] Perhaps his most damning observation was that, until training could be rectified, the ‘troops of the Commonwealth cannot in themselves be regarded as fit for active operations in war’.[9]

In response to the identified deficiencies, Hutton set about introducing a more methodical and scientific training approach which had not been adopted by colonial forces prior to 1901. He established schools of instruction for the light horse, artillery, engineering, infantry, medical services, and supply and transport arm of the CMF. He also encouraged an increase in the duration of field training.[10] However, his system of schools of instruction was hampered by a lack of permanent staff, and the militia struggled to secure sufficient time away from their civilian employment.[11] To address these issues, Hutton commenced lobbying the government to establish a permanent military college to provide trained staff officers and to build industry to support the provision of small arms, artillery pieces, and ammunition.[12] While the establishment of a permanent military college would not be achieved for another decade, Hutton’s reforms and lobbying kick-started the modernisation and professionalisation of the CMF and the development of an Australian defence industry. But Hutton’s influence was not entirely positive.

‘For King and Country’. Understandably, Hutton saw his world through the lens of the British Empire. John Mordike, in An Army for a Nation, explains that Hutton regarded the colonial militias as part of the much larger imperial organisation. Hutton wanted to establish a cooperative scheme between Britain and the militias; he envisioned mounted troops from Australia becoming part of an imperial force for service outside of Australia.[13] It is here that Hutton ran headlong into competing priorities between Britain’s imperial objectives and those of the newly formed Australian Government. As the Australian Government considered early drafts of the Defence Bill in1902, the ruling Labor Party removed the General Officer Commanding’s power to commit troops to overseas service. The Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, was particularly wary of committing to an imperial military reserve that could deployed outside of Australian territory.[14] In his view, Australia’s interests centred on defence of the newly established country, and economising on military costs. This view demanded that Australia maintain the freedom to select when (and if) its national interests would be served by supporting the Empire in a foreign war.

By contrast to the Australian Government’s reluctance to position Australian troops for overseas service, Hutton was a British officer with a vested interest in generating a colonial force capable of supporting the collective security needs of the Empire. He cautioned that restricting overseas service to voluntary organisations meant that Australia risked having to organise bespoke military units for active service at the very moment when their service was required.[15] Interestingly, Hutton saw a field force of about 20,000 Australian mounted troops as an appropriate number for an imperial commitment. While it may be coincidence, this is precisely the number of expeditionary soldiers discussed by the Australian Government during the 1902 negotiations over the Defence Bill, and the same as the number of troops initially committed by Australia to both the First World War and the Second World War.

A Rising Threat. Hutton’s training reforms and discourse on how best to defend Australia brought to the fore the difficulties associated with the sheer size and dispersed nature of Australian population centres and military forces. Many commentators regarded compulsory military training as one way to bridge this gap. But to explain how Australia introduced compulsory military training it is first necessary to review the international events that unfolded from 1904.

By February 1904, Russia and Japan were fighting a land and naval campaign against each other in Manchuria. Australian newspapers were quick to report on the threats that a dominant Japan might pose to the national interests. For example, the Newcastle Herald in March 1904 declared that ‘an ultimate triumph by Japan would be calamitous’ for Australia.[16] In August, WE Abbott, a prominent New South Wales politician at the time, wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald that based on the threat in the Pacific ‘up to this time our contributions to the defence of the Empire has been contemptible’ and that ‘half-hearted attempts at our own defence have been ridiculous’.[17] The sentiment from across Australia was becoming clear: the regional threat posed by Japan brought into stark clarity the nascent nature of Australia’s defence capabilities.

In 1905, the defeat of the Russian Fleet at the Battle of Tsushima crystallised two major shifts in Australian defence thinking. The first was the realisation that Australia required a naval force to protect its interests; the second was that Australia’s military planning was inadequate to confront an external threat.[18] By this time, Prime Minister Alfred Deakin had decided that nothing short of the Swiss system[19] of universal military service would provide Australia with an effective defence scheme.[20] Threats from the north, and an acknowledgment of the undoubted deficiencies in Australia’s military capability, prompted the government to reinvigorate military planning and saw defence issues gain prominence.[21]

Mobilisation Strategy. Following the 1907 Colonial Conference,[22] the Australian Government considered the introduction of a defence scheme to remediate identified shortfalls in military capability, particularly for personnel and equipment. The proposed scheme comprised a standardised approach to the training and equipping of the Army (a version of universal service[23]) and a precautionary stage of mobilisation for which Great Britain would provide strategic warning.[24] The Chief of the General Staff of the Australian Forces, Colonel William Throsby Bridges, initiated work to develop a strategy designed to provide Australia’s six states and three military districts with explicit instructions on how to mobilise as a part of the CMF. Over the next six years, plans were drafted including guidance on how to raise, train and sustain military units. Subsidiary plans addressed matters such as how to use the media to recall militia and what measures might be necessary to limit press freedom in order to ensure operational security.[25] While planning was incomplete at the outbreak of the First World War, it nevertheless provided initial direction to the district commandants and supported Great Britain’s call for Australia to enter a precautionary stage of mobilisation.

In early 1909, following considerable debate, the Australian parliament introduced the Universal Training Scheme (UTS) to meet the increasing demands for military personnel. The scheme was colloquially known as ‘Boy Conscription’, as 12 to 21 year olds were brought in for military service, either with the permanent force as cadets or within militia units.[26] Despite its introduction in 1909, the scheme did not register eligible males until 1911 and did not commence training them until July 1912.[27] This three-year delay undoubtedly reduced the number of trained service personnel serving across the states in the militia, and most likely limited the level of experience attained by soldiers before the outbreak of the First World War. Following the initiation of the scheme, the Australian Government invited Field Marshal Lord Horatio Kitchener to review Australia’s defences.

In November 1909, Lord Kitchener commenced a six-week tour of Australia to assess its defences. His damning conclusions identified that Australia’s Army was inadequate in number, training and organisation.[28] Notably, Lord Kitchener recommended that Australia use the newly introduced UTS to raise and train the CMF up to a total strength of 80,000 personnel.[29] Further, he recommended that the force should consist of 84 infantry battalions, 28 regiments of light horse, 49 field batteries, seven howitzer batteries, seven communication companies and 14 field engineer regiments.[30] Such a force necessitated that approximately 1.8 per cent of the Australian population be trained for war service—a major investment and a considerable change from practices at that time.

Lord Kitchener’s recommendations reflected a desire to increase the depth of trained military personnel in Australia who could defend against raids or invasion. However, under the 1903 Defence Act, personnel called for service under the UTS could not be utilised outside of Australia or its territories.[31] This restriction limited the CMF to roles in the direct defence of Australia. Should Australia need to contribute to British imperial efforts or to Australian-led expeditions overseas, bespoke military elements would need to be raised.

In addition to his observations concerning force design and workforce, Kitchener identified deficiencies in professional military leadership. Military officers in Australia at the time were not professionally trained and there was no formal process of application to a centralised authority. Instead, a vacancy at a unit had to exist and a candidate was recommended directly to the commanding officer. Potential candidates received no formal professional military education, and selection often owed much to an individual’s social status and level of education.[32] Officers were trained based on the interests of the commanding officer, and skill levels varied widely across the force. While militia battalions were trained by permanent warrant officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs),[33] very little attention was given to developing professionalism among officers who led the CMF. Instead, most of the time and effort went into training on drill and musketry.[34] To rectify this shortfall in professional military leadership, Lord Kitchener, as Hutton had done previously, recommended the creation of a military college based on the model of West Point in the United States to train what he called a ‘Staff Corps’.[35]

Formalised training regimes had a profound effect. The creation of the Royal Military College—Duntroon (RMC) enabled Army to concentrate efforts into the development of professional military education in a way not previously achievable.[36] Professionally trained officers were valued for their knowledge, organisational skills and logistical expertise, and they saw service in the regular Army. In addition, it should be highlighted again that the CMF comprised two elements. The Citizens Forces made up the bulk but were part-time reservists commonly referred to as militia soldiers. By contrast, the Permanent Forces were full-time service personnel who fulfilled essential administrative and instructional functions. Reform also touched the leadership of militia units, with professionalisation of citizen officers also being considered. Specifically, Lord Kitchener proposed that citizen soldiers who showed potential as future leaders should be appointed as officers in the militia as early in their career as practicable. This was to ensure that citizen officers had opportunities to develop proficiency in military drills through repetition, and sufficient time to study their duties and profession.[37] It is important to highlight that legislation was subsequently passed that established RMC as the sole vehicle to train and promote permanent officers into the Staff Corps. As Darren Moore highlights in his history of RMC, the Staff Corps was only responsible for the instruction and administration of the Permanent Forces. By contrast, commanders for the militia would only be drawn from within their own ranks and not from the permanent officers of the Staff Corps.[38] Lord Kitchener’s efforts to improve the quality of staff officers was taken seriously and implemented rapidly, but his recommendations were not all encompassing.

While Lord Kitchener’s report dealt with the defence of Australia, it lacked attention to an offshore scenario. This was a glaring omission considering Australia’s contributions to the Crown during the Second Boer War, but undoubtedly reflected Kitchener’s understanding of previous tensions between Hutton and the Australian Government on the issue. Despite this omission, conversations about overseas service did occur. Between 1910 and 1913, the Minister for Defence undertook studies to determine how Australia and New Zealand could respond to an offshore military scenario.[39] In 1912, brief discussions between New Zealand and Australian military staff determined that both countries could raise and support a combined division for operations offshore;[40] New Zealand would contribute 8,000 men and Australia 12,000 men. It is not surprising that only brief discussions were held about a combined division and its preparation or use. Prior to the First World War senior Australian officers had little scope to achieve collective training at the battalion or brigade, let alone divisional, level.[41] This void relegated discussions about such training to the conceptual rather than practical level. Consider also that a joint response to an overseas conflict would have been politically sensitive in both the Australian and New Zealand parliaments if leaked. Despite these restrictions, the brief work conducted on the combined division formed the basis for planning when both Australia and New Zealand committed troops to the First World War.[42]

Shortly after the declaration of war on 4 August 1914, the CMF started mobilising to fulfil a 10 August 1914 offer made by Australia to the British Government of 20,000 personnel for overseas service.[43] Given the restrictions imposed on overseas service by members of the CMF, on 31 August 1914 the all-volunteer 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was raised as a wholly new and separate organisation in order to contribute operations beyond Australia’s shores. Volunteers were necessary, as personnel enlisted under the UTS could not deploy outside of Australia. As Hutton had cautioned in 1902, restricting overseas service to voluntary organisations meant that the CMF was now required to organise bespoke military units for active service at the very moment when their service was required. An unintended positive effect of Hutton’s earlier lobbying and introduction of the UTS was that indigenous military industry now existed to manufacture small arms, ammunition, clothing, and military supplies. This industry supported the mobilisation of the 1st AIF.

On 1st November 1914, the 1st AIF troop transports departed Western Australia for Europe—later diverted to Egypt. The AIF comprised 881 officers and 19,745 soldiers.[44] Of these officers only 24 had no previous military service, and of the soldiers only one-third had no military service.[45] Notably, officers were primarily drawn from old militia lists or were volunteers from the Citizens Forces, vice those from the Permanent Forces or the Staff Corps.[46] Many Staff Corps officers were instead retained for service within Australia to ensure the functioning of the CMF—a critical decision for ongoing mobilisation efforts as they were able to raise, train and sustain elements in the field. Australia’s ability to mobilise over 20,000 men for active service overseas in just 21 days was a feat made possible only by the undertakings of both government and the military in the years that preceded conflict.

Key Observations. In Australia, the years leading up to the First World War were defined by profound changes in defence policy and approaches to mobilisation. The deteriorating global security landscape, starting in 1905, forced the issue of national defence into the minds of politicians and military professionals alike. The debates about and eventual establishment of the UTS had several positive influences on the country’s ability to mobilise (readily available forces, force structures, defence industry) but nevertheless imposed major restrictions (limited to service within Australia). The review of Australia’s defences by Lord Kitchener provided a growing sense of urgency, as well as the grounds, for Australia to better prepare itself for mobilisation and its own national defence. This was especially true with respect to the need for professional military leadership of both the CMF and the AIF. The Australian experience at the outset of the First World War demonstrated that the pre-prepared combined division force structure aided in the mobilisation of the AIF even if it was not used. Finally, the ability to draw upon leadership from the CMF with military skills, knowledge and training ensured Australia was able to deploy the AIF in an expeditionary role. Mobilising 20,000 men for overseas service in 21 days was an admirable feat and involved a process that would be repeated for the Second World War.

Ramping It Up—Second World War Mobilisation

Few Australians would have been spared a direct link to the effects of the Great War, later known as the First World War. Australia had seen just over 400,000 enlist into service—from a population of roughly four million, amounting to nearly 10 per cent of the total population.[47] As a result, the effects of the First World War were still sharp in the minds of politicians, the serving military, military veterans, and the Australian public when war was again declared on 3 September 1939. In response to the deteriorating global strategic situation, the pre-war period saw the Australian Government rush to rectify shortfalls in defence policy, while many of the lessons from the First World War went ignored or were inadequately addressed. Ultimately, Australia was no better prepared for the Second World War than it was for the First World War.

Budgetary Restrictions. Massive military expenditure during the First World War was followed by an equally huge budget reduction in the post-war period. Defence policy of the 1920s was based on three guiding principles. The first was that the possibility of another war was remote; after all, as described by HG Wells and the United States President, the First World War was the war to end all wars.[48] However, this forecast proved idealistic. Conflicts remained unabated in mainland Asia, in Eastern Europe and in Turkey, and humanity’s natural tendency to make war at a global level was confirmed only 20 years after the end of the First World War. The second principle was that Australia had significant war debts to repay and needed to drastically restrict spending.[49] It is not surprising that successive governments wound back spending across defence and other departments as they attempted to correct the nation’s debt to gross domestic product ratio and return the economy to pre-war standards. The third principle was the belief that if another war did occur, Britain could be relied upon to defend Australia from its forward bases in Singapore—an assumption predicated on the strength of the Royal Navy.[50]

During this period, the British Government was committed to the so-called ‘10-year rule’, which held that no war would occur within a warning time of a decade.[51] However, the global security landscape declined rapidly between 1931 and 1939. Australia observed the deteriorating strategic environment from 1931 with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria; in 1933 the Nationalist Socialist Workers Party (NSDAP, or Nazi Party) gained control of Germany; in 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia; and in 1936 the Spanish Civil War erupted. Not surprisingly, the combination of these events prompted military and governmental officials to reconsider their defence policy, expenditure and posture.

From 1933, Australian defence spending increased in response to the deteriorating global security landscape. At first, budget reform focused on funding a naval-centred approach that supported Britain through the Singapore Strategy.[52] Under this concept, the Army was only required to provide a force capable of defending Australia against enemy raids.[53] The realities of the strategic environment, however, initiated a change in defence thinking. The 1937 Imperial Conference reminded attendees that the earliest phase of any war would be the most dangerous to Britain and the dominions.[54] This realisation elevated the need for military measures to be taken during peacetime to enable early military contribution in any conflict. Indeed, the British Imperial General Staff noted that the earlier divisions from the dominions could be dispatched to support a crisis, the more value to the war effort they would be.[55]

Despite the experience of the First World War and discussions at the 1937 Imperial Conference, Australian policy remained focused on an Army that was limited to service in Australia and in Australia’s own defence. Organisational reform following the war resulted in a structure that included four infantry divisions, three mixed brigades capable of forming a fifth division, and two cavalry divisions. While this represented a powerful capability on paper, in reality these were skeleton units.[56] These units were fortunate if they managed to maintain a strength of 25 per cent, denuding the professional force of realistic training opportunities, and leaving significant hollowness to be remediated in the event of conflict.[57]

In the late 1920s, Army’s capabilities had been further eroded. The Wall Street stock market crash of October 1929 led to an acute global trade depression. To limit government expenditure, the UTS was suspended on 1 November 1929. Five infantry battalions and two light horse regiments were also abolished to conserve resources.[58] By 1931, the Australian Military Forces (AMF) (now made up of the Militia and the Permanent Military Forces) were in crisis.[59] Funding for training, equipment and salaries was progressively reduced from £1,239,395 in 1929–1930 to £978,144 in 1932–1933.[60] A comparison of military strength is illustrative of the depth of the crisis: during the interwar years, the permanent and militia forces lost 50 per cent and 70 per cent of their workforce respectively.[61] By 1931, the AMF consisted of just 1,544 permanent and 27,400 militia personnel. These numbers were lower than those recorded at Federation in 1901. This was despite a 90 per cent increase in the Australian population over that same period.[62]

With each funding cut and personnel reduction, the AMF lost more personnel capability and experience. Training and courses were limited, and more battle-experienced AIF veterans aged out of service annually. Gaining access to resources for training courses and schools became a constant source of tension. For example, personnel earmarked for promotion to lieutenant colonel had to complete the course titled ‘21A’. This course was six days long and included formal lessons, tactical exercises without troops, unit-level command instruction, and introduction to brigade operations. This training, while essential, was still regarded as insufficient to properly prepare officers for command at battalion and regimental levels, and under-resourcing exacerbated the problem (as a comparison, the British equivalent of 21A ran for three months and was still considered too short by the British Army).

The atrophy in professional training was felt acutely at RMC. Gavin Long, the general editor of the Official History of Australia in the Second World War, explains that from 1911 the college had increased its class sizes from 35 to approximately 60 cadets per year in the 1920s and that it was producing professional military officers with the requisite skills to perform staff appointments across a wide range of functions. As the effects of the Great Depression took hold, however, cadet numbers were reduced and the Duntroon barracks was closed in favour of Victoria Barracks in Sydney.[63] By 1931, barely 30 cadets were being trained annually, in contrast to the 60 cadets trained every year in the 1920s. As Prime Minister Menzies announced the beginning of Australia’s involvement in World War II, Army’s decision to reduce class sizes (by roughly 30 cadets per year) meant that there were now 270 fewer professionally trained staff officers available to support the war effort (the permanent force at this time was roughly 3,500 personnel, and 270 officers would have represented an 8 per cent increase in available workforce).

Army’s training efforts during the interwar years has been described by Garth Pratten as having a professional ethos but with amateur standards.[64] Instead of regressing to the drill and ceremonial parades of the pre-Federation period, Army training was gradually improved with staff and field exercises involving the use of machine guns and mortars.[65] These efforts were focused on practical measures to ensure that officers and NCOs had the requisite skills to raise units, train them, and command them on active service.[66] These changes reflected an organisational drive towards achieving uniformity of standards and emphasised the importance of training officers and NCOs for higher command and staff roles in case of a mobilisation event. Further, following the observed and proven success of training schools during the First World War, promotion courses and written examinations were introduced and expanded. With limited opportunities for officer training in Australia, many officers and NCOs were instead sent to Britain, or elsewhere across the Empire, to train, learn, and share ideas. Demonstrating the importance of such opportunities, the chief instructors of both the Small Arms School at Randwick and the School of Artillery at South Head were appointed only after they had qualified for the position by attending training at British institutions. By studying overseas, members of the AMF accessed up-to-date training methods to bring back to Australian courses. Experience gained on overseas courses was viewed favourably, as was experience gained during the First World War.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Army adopted the policy that all officers selected as battalion commanders needed First World War experience.[67] While this policy was highly useful in the 1920s, it led to a stagnation of new talent rising through the militia in the 1930s. First World War veterans, unsurprisingly, reinforced doctrinal teachings applied during the First World War. In some cases, these lessons had to be tempered and updated based on the information exchanges occurring overseas, particularly in England and India.

In 1938, Army was finally funded to establish a command and staff school (C&SS). Critically, this school was open to both militia and permanent staff corps officers who were to be trained in strategy, tactics and administration.[68] This measure aimed to rectify tactical training and administrative shortcomings experienced during the First World War. Regrettably, it offered too little too late to impact more than a handful of officers by the commencement of conflict in September 1939. The establishment of C&SS did, however, create an indigenous capability for the AMF to train its people. Indeed, the school still operates today (though with a significantly altered remit and under the name Australian Command and Staff Course). Ultimately, the Australian Army of 1939 was little different to that of 1914 in terms of size, preparedness and training. Regardless, it would provide the nucleus of professional military talent for rapidly expanding the Army. What was missing was whole-of-government coordination for mobilisation.

Mobilisation of the Force. While budget and personnel reductions had dealt a heavy blow to Army capability, the interwar period had nevertheless seen it begin to develop mobilisation strategies that could support the defence of Australia in a deteriorating global security climate. The first degree of mobilisation involved Army providing coastal defence in the event of war with a distant enemy. The second envisaged a situation in which minor raids onto Australian soil could be repelled using a force of approximately two divisions (while the structure was there on paper, issues of hollowness were not addressed). Finally, the third degree of mobilisation—full mobilisation—was intended to counter a full invasion. It required complete mobilisation of the AMF’s five infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions to defend Australia from outside aggression. Full mobilisation would need upwards of 200,000 personnel and a whole-of-government approach to building the force.[69]

Critically, none of Army’s mobilisation strategies considered service overseas and all remained dependent upon voluntary recruitment. Suspension of the UTS in 1929 meant that to mobilise any force within Australia required a voluntary approach. In 1938, the government authorised the militia to expand to 70,000, and a formal recruiting campaign was initiated. Contrary to a pervasive 1920s anti-war sentiment, by the late 1930s many Australians were acutely aware of the threat posed by Japan in the Pacific and the rise of Nazi Germany in Europe. As a result, the recruitment campaign was a raging success. The Militia was successfully expanded from a force of 35,000 in September 1938 to 70,000 by March 1939.[70] As had been the case in the First World War, Australian men were willing to volunteer in large numbers for service where there was a clear and identifiable threat. While the Militia remained confined to service within Australia, recruitment out of the Militia became a mechanism through which Australia could access a nucleus of dedicated officers and NCOs who were experienced in commanding sections, platoons, companies and battalions.[71] As Craig Wilcox observed in For Hearths and Homes: Citizen Soldiering in Australia 1854–1945, by the 1930s, citizen soldiers had become the tool to teach citizen officers how to organise, supply, deploy and lead their men.[72]

With the threat of war looming, and military personnel numbers increasing, in 1939 the Australian Government hastily published the Commonwealth War Book. This document was designed to provide cross-coordination of departmental action in the event of strained international relations and on the outbreak of war.[73] In reality, Jeffrey Grey explains, the Commonwealth War Book was a necessary measure but amateurishly executed.[74] The book was released without chapters on manpower or supply, and excluded considerations for the mobilisation of the civilian populace. When the declaration of war between Britain and Germany was announced on 3 September 1939, Australia was caught in a period of correction: it was scrambling to rectify the atrophy of the 1920s and early 1930s to enable mobilisation for a large-scale war.

Mobilisation of the Army commenced shortly after the formal declaration of war. The coastal defences of Australia were crewed, and the militia was mobilised at a rate of 10,000 every 16 days to provide guards to vulnerable points.[75] These actions were in keeping with the concept for first-degree mobilisation. Following the experience of the First World War and the 1937 Imperial Conference, it came as no surprise when the British Government requested (on 8 September) that Australia provide an expeditionary force for overseas service at the earliest possible time. While defence policy still precluded use of the AMF outside of Australian territory, work had been carried out from the mid-1930s to generate a force that could be made available for overseas service. This work, known as Plan 401, formed the basis on which to mobilise and deploy forces for service offshore.[76] As in the First World War, the Army was faced with the necessity of mobilising the Militia for homeland defence at the same time as mobilising a division (the 6th Division of the 2nd AIF) for service overseas.

On 15 September 1939, the Australian Government confirmed the raising of the 6th Infantry Division, 2nd AIF, for service overseas. At the same time, the mobilisation of the Militia was increased from lots of 10,000 to lots of 40,000 men, and training expanded from 16 to 30 days.[77] Long explains that nearly all the senior military leaders, divisional commanders and brigade commanders, and most unit commanders, of the 6th Infantry Division had previously served as regimental officers during the First World War.[78] In fact, at the outbreak of war, 43 out of 54 battalions in the AMF’s order of battle were commanded by First World War veterans.[79] There was nevertheless a critical shortage of professional regular officers to fill key staff posts (in this regard, the benefit of hindsight underscores the opportunity that was lost to fill these positions when the 270 officer positions were withdrawn from RMC). With an inadequate number of regular officers in service at the outbreak of the Second World War, the Prime Minister directed that priority was to be given to filling key positions and staff appointments across the military districts of Australia. The exclusion of permanent officers from command appointments in the 6th Infantry Division caused annoyance and disappointment among their ranks, but was grounded in the government’s acknowledgement that these officers were needed to support force generation;[80] their primary responsibilities were to keep the militia, their skills and the Army headquarters operating, as professional training and experience were in short supply. Furthermore, retention of staff corps officers inside Australia was influenced by the War Cabinet’s fears regarding the intentions of Japan; Cabinet needed to retain a sound military base for training the AMF in case of invasion, and the permanent officers of the staff corps provided this stability.[81]

The requirement to fill both expeditionary and defence of Australia units quickly raised concerns regarding workforce availability. As a result, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced on 20 October 1939 the reintroduction of compulsory military service.[82] It had been nearly 10 years to the day since the old UTS had been halted by government. Now, using the powers of the Defence Act 1903, the Governor-General called up all specified persons, males aged 18, to ‘enlist and serve’ in the militia (at this time for service in Australia only).[83] This announcement had two key effects: (1) it started to bring the militia up to full strength and commenced broad training programs across the military districts to achieve their defensive tasks, and (2) it provided an additional pool of trained personnel who could, if they desired, volunteer for service with the expeditionary forces at a time of their choosing. As with the First World War, the Army in the Second World War had little difficulty in meeting its initial personnel targets. The perceived existential threat to Australia triggered an associated desire among men of military age to serve in the militia. Interestingly, so successful were the initial recruiting drives that Army had received an additional 50,000 enlistees with whom it could fill an additional two divisions at its discretion.[84]

Despite the rapid availability of new recruits, the impact of training day reductions and lack of access to equipment and professional military leadership were keenly felt across the entire AMF. The permanent officers overlooked for command appointments had, in many cases, served in positions as lieutenants or captains for extended periods with poor prospects of promotion. The professional knowledge and experience they had gained, many on the front lines of World War I, made them nearly irreplaceable and essential to the operation of the military organisation as a whole. When the 6th Division of the 2nd AIF commenced its transportation to North Africa in January of 1940,[85] it had only achieved platoon-level training, at best. As a result, it conducted training serials overseas throughout 1940 until the formation was committed to combat in January of 1941 at the Battle of Bardia.[86]

The practice of militia officers receiving command appointments over permanent officers continued as the 7th and 8th Divisions were raised in February and June of 1940 respectively. Long highlights that in these divisions the commanders had limited access to permanent officers, whose skills were in demand across the entire organisation.[87] Despite the desire for more permanent and professionally trained officers, the importance of the militia’s capacity to provide the expeditionary forces—with a trained pool of officers and NCOs—cannot be overlooked. Pratten notes that General Blamey oversaw the selection of commanding officers for the newly raised divisions. He also asserts that there are strong indications that Blamey selected these men only as caretakers to raise and train the battalions while younger officers learned their trade and prepared to take command on active service.[88] Pratten also notes that the skills of the militia commanding officers were commendable. From their experience in the First World War to that gained through their roles in white-collar jobs, he argues, they were particularly well prepared for the task of training and organising new units for war.[89] It was access to this trained talent pool that provided the nucleus for the rapidly expanding new divisions. It also created a dilemma for the defence of Australia: how to fill the militia if its members kept volunteering for overseas service.

By July 1940, the three new divisions slated for the AIF had filled all their necessary enlistments. Unfortunately, there remained extreme shortages of junior officers and trained NCOs. As a result, Grey notes, not all officers and their units performed as well during combat as others, and they suffered from poorly trained reinforcements.[90] Grey’s assessment of the situation is not surprising. It was not until 1942 that permanent schools were established in Australia to improve the quality of reinforcements and their training.[91] These schools were the modern incarnation of Hutton’s schools of instruction. The importance of training institutions echoes to the modern day—demonstrating that dedicated training establishments need to operate before conflict occurs, even if they have to be run at a reduced capacity. Despite the late establishment of schools, access to a trained militia and permanent workforce (albeit at differing levels) enabled rapid expansion of the Army to support mobilisation across the AMF. Without the depth of professional military leadership and training provided by the reinvigorated militia, it is likely that the Army would have experienced much greater difficulty, and further delays, in mobilising expeditionary forces for service overseas. Considering the 6th Division trained for nearly 15 months before being employed in combat, further delays in mobilisation could have seen Australia’s wartime contributions taking nearly two years to reach employability—an unsatisfactory outcome.

Key Observations. Despite the challenges faced, mobilisation of the 6th Division, and subsequently the 7th, 8th and 9th Divisions in quick succession, was a significant achievement. It is particularly notable that Army’s ability to draw upon both a permanent and a militia workforce, with knowledge and experience of warfare, was fundamental to the achievement of national mobilisation. Indeed, it is apparent from these events that knowledge of war empowers its execution. This observation, and its relevance to modern warfare, will be the subject of the next section.

Source: Defence Image Gallery

Knowledge Is Power: Cracking the Code

The contemporary Australian Army has no practical experience of mobilisation beyond its current force structure. There is, however, relevant knowledge management inherent within the organisation. Knowledge management is a modern term used to recognise that leveraging already accumulated knowledge is the most beneficial way for organisations increase their competitive advantage.[92] The term describes a relatively new and discrete field of academic study. However, the concept has arguably been in existence since the first cave paintings were used to record hunting practices. In essence, knowledge management deals with the intellectual capital that is contained within a workforce and how it is trained, maintained and then utilised. In a military context, Army’s ability to use its inherent military knowledge and expertise, and to adapt it to government direction (such as direction to mobilise quickly and efficiently to provide fighting power more quickly than potential adversaries), offers an asymmetric advantage against state and non-state opponents. To better understand how Army can leverage knowledge management, it is instructive to understand the different types of knowledge and how they can provide asymmetric advantage in a military sense.

Knowledge management, as an academic study, came to the fore in post-war America during the 1950s. The introduction of the GI Bill and the scientific advancements from the Second World War produced a workforce that harboured vast amounts of knowledge. In 1959, the term knowledge worker was coined by Peter Drucker.[93] He explained that, due to higher levels of education, workers had an unprecedented ability to learn and then apply theoretical and analytical knowledge. By the 1990s, knowledge management had become mainstream in the business world and was a distinct academic discipline. Both the corporate world and academia recognised the importance of knowledge management and how it contributes to finding and maintaining competitive advantage.

Based on the available literature, defining knowledge management is an elusive task, with definitions spanning various fields of study and practice. The term includes aspects of physical technology to manage and enable the passage of information and an individual’s cognitive ability to execute tasks. Effective leadership is also critical to ensuring knowledge management is incorporated and applied with strategic direction. It also requires a culture based on collectively sharing and thinking about problems. Some definitions are set out below:

- Knowledge management is the leveraging of collective wisdom to increase responsiveness and innovation.[94]

- Knowledge management is the systematic, explicit, and deliberate building, renewal, and application of knowledge to maximise an enterprise’s knowledge-related effectiveness and returns from its knowledge assets.[95]

- Knowledge management is getting the right knowledge to the right people at the right time so they can make the best decision.[96]

- Knowledge management is the formalisation of, and access to, experience, knowledge, and expertise that create new capabilities, enables superior performance, encourages innovation, and enhances value.[97]

All of the definitions listed here have their place. In a military context, however, the fourth definition is the most useful in helping to understand how Army might achieve asymmetry during a mobilisation event. Specifically, it highlights the creation and storage of knowledge, it emphasises experience, and it clearly articulates an end-state of enabling superior performance. This paper accepts this concept of knowledge management as a baseline requirement of the ADF.

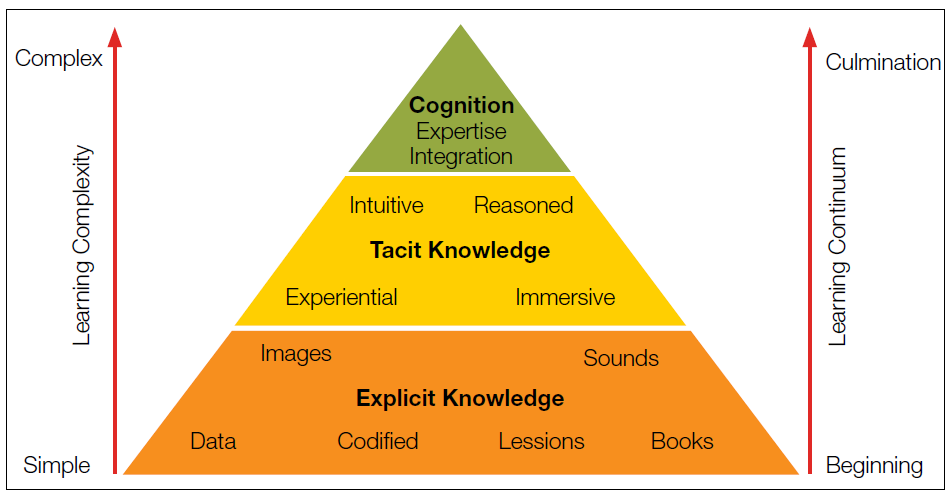

Underpinning knowledge management are the two underlying types of knowledge itself. In 1966, Michael Polanyi provided the pre-eminent explanation of knowledge and provided definitions for the two types.[98] He classified knowledge according to its complexity and identified a continuum that ranges from explicit to tacit. Explicit knowledge is that which is articulated in formal language and can be easily transmitted to others.[99] Conversely, tacit knowledge is embedded in individual experience and involves intangible factors such as beliefs, instincts, and values.[100] Understanding explicit and tacit knowledge is a key factor in ensuring an organisation has the expertise to perform at a superior level.

When considering the elements of knowledge management, it is relevant to consider that one is physical (explicit knowledge) and the other is human (tacit knowledge). This means that an organisation needs to achieve a balance between the two, recognising that the most complex form of knowledge (tacit) is held within the human dimension.

Explicit Knowledge

Organisations such as the ADF use core documents such as doctrine to store data, techniques and procedures to share explicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge can also comprise a range of data, text, sounds and images that can be expressed to learners through books, lessons, oral briefs or physical examples. One of the challenges in harnessing explicit knowledge is its sheer volume. There is no shortage of doctrine, academic papers, internal briefs or recorded media that try to help military professionals understand their roles and how to execute warfare. The multitude of information sources can, however, become overwhelming. Indeed, our modern capacity to store and generate explicit knowledge related to warfare is far beyond the capacity of a single human to absorb. Nevertheless, the study of explicit knowledge enables people to learn about, understand and deepen their knowledge of the roles and functions required of them within an organisation. What explicit knowledge does not provide, however, is the intuitive ability to perform those roles and functions. This factor is critical to tacit knowledge.

Tacit Knowledge

Tacit knowledge is gained through the experiences of individuals and builds upon the foundations of explicit knowledge. One of the fundamental characteristics of tacit knowledge is that it is difficult to translate into an explicit form. An example of this is riding a bicycle; people learn how to do it, but it is incredibly difficult to explain how to achieve balance before accomplishing it yourself. For this reason, tacit knowledge is acquired through a process of socialisation where an individual learns skills through immersion.[101] Understanding immersion is critical. For example, while military schools may teach the theory, component parts and mechanics of a platoon attack, students will only have a rudimentary capacity to perform the function until they also have opportunities to immerse themselves in the skill being taught. Only through continual immersion will students be able to build their tacit knowledge, improve individual performance, improve collective performance, and eventually achieve cognition in the task.

The iterative and immersive process of achieving tacit knowledge explains why value exists in conducting yearly training cycles and build-ups to higher echelon training. Importantly, these activities build a repository of experience and knowledge that becomes more intuitive, immersive, experiential and reasoned as they increase in frequency; they help an individual in reaching a level of cognition.

Source: Created by the author.

Achieving Cognition

Cognition is the cumulative impact of both explicit and tacit knowledge. It is the linkage between these two types of knowledge and how an individual links that knowledge to a process.[102] The process of cognition is grounded in how an individual decides based on their available knowledge and their application of that knowledge in each situation. Figure 1 graphically depicts how knowledge leads to cognition using the building blocks of explicit and tacit knowledge. In essence, cognition is achieved through the application of accumulated experiences to determine the best outcome in response to a threat or an opportunity. For the military, individuals who build upon explicit and tacit knowledge to achieve cognition provide their organisation an advantage.

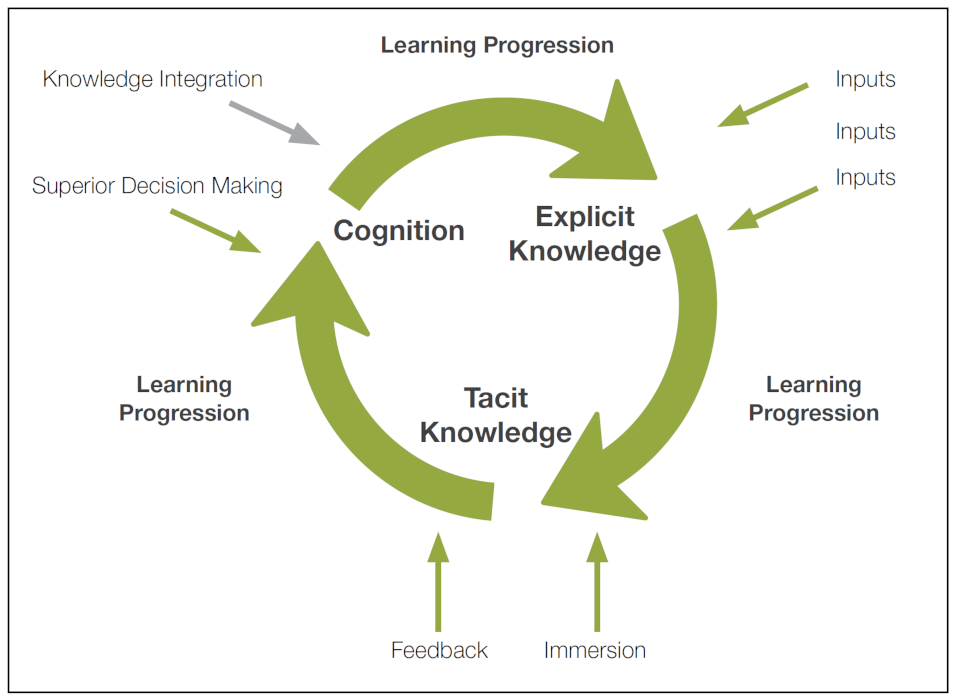

Source: Created by the author.

When reviewing the existing literature on knowledge management, one finds an evident weakness in explanations concerning the progression from explicit knowledge to tacit knowledge and thence to cognition. For example, while Figure 1 depicts a progression, it does little to explain how the transition between the elements occurs, or what happens when new knowledge is encountered. The progression is presented as a linear process with the culmination occurring once an individual reaches the desired end-state of cognition. The figure fails to factor in new knowledge that becomes available, new periods of learning that take place, or the opportunities presented by new trials or experimentation, and so on. To better explain the process, Figure 2 graphically represents how knowledge progresses in a cyclical rather than in a linear fashion. It highlights that, as an individual progresses through their access to accumulated knowledge, they also have the continued opportunity to learn. This could be achieved through self-reflection, or through their access to more explicit knowledge. Equally, it might be achieved by an individual being considered for promotion. In the military context, such individuals may gain access to knowledge associated with professional career courses and will gain a greater knowledge base once they achieve rank progression and with increasing exposure to tacit experiences. If nothing else, Figure 2 articulates that knowledge management should be viewed as a continual process rather than a linear one. Viewing the process as a cycle emphasises continued learning by progressive improvement in an individual’s access to knowledge and their performance in a chosen field.

Relevance of Knowledge Management to Military Capability

Knowledge management is critical in efforts to gain an asymmetric advantage and to understand how that advantage can be capitalised upon. As the definition explains, knowledge management is the formalisation of, and access to, experience, knowledge and expertise that create new capabilities, enable superior performance, encourage innovation and enhance value.[103] It is for this reason that organisations such as the ADF have invested heavily in building and staffing educational facilities, providing structured career courses, and conducting continual training serials for their people and units. The value of these measures is based on hard-won lessons from combat, and has often been learned after much bloodshed. In his 2021 analysis of German and British tactical officer training during the interwar period, Ashley Arensdorf concluded:

a military culture that stressed technical proficiency, rewarded intellectual aptitude, regarded war as the harshest test of the individual, and sought to create an officer who could act decisively and quickly under the stress of realistic battlefield conditions was definitely superior to one that lacked these characteristics.[104]

Structured training systems that deliver relevant and realistic training, and that allow for experiential gain through continued practice, undoubtedly provide an advantage over systems that do not.

Organisations that understand knowledge management and incorporate it into their developmental models will hold an asymmetric advantage over those that do not. The people within these organisations who can progress professionally through explicit and tacit knowledge towards cognition provide their organisation with greater capacity to deal with threats, make superior decisions and seize opportunities. ADF doctrine and training is based on historical learning and has proven results supported by continued academic research. Knowledge management is therefore an essential element in maximising organisational performance and (in a military context) achieving asymmetric advantage.

Thoughts for the Future

Exploring Army’s Edge

Source: Defence Image Gallery

In 2020, a paper co-authored by a former Chief of Defence Force accused the Army of being a glass cannon—capable of one big shot and then breaking.[105] This was a particularly graphic and emotive metaphor based primarily on an assessment of Army’s limited access to platforms and equipment such as strategic lift, logistics, and armoured vehicles. Lacking in this critique was an adequate appreciation of Army’s most valuable asset: its people. What the paper intimated, but never explicitly explored, is that Army’s edge comes from its ability to scale. Arguably, Army’s ability to scale relies heavily on the organisation’s access to a trained workforce to provide the launchpad for mobilisation if required by government. As Army moves through the 2020s and into the 2030s, access to a trained workforce will be of critical importance to achieving asymmetry during any mobilisation event.

Since Federation, the Army’s workforce has undergone a gradual but deliberate progression from one that favoured part-time militia forces to one that comprises a small regular professional force. This shift is understandable. Australia after Federation experienced limitations with a nascent military establishment, and learned lessons about access to trained and experienced personnel from its involvement in the Second Boer War, the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean War, the Malaya Emergency, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, operations in East Timor, and Australia’s military contribution to the Global War on Terror. As a result, Army has seen a progressive increase in regular force numbers, with commensurate decreases in reserve (militia) numbers (see Table 1).

Associated with the growth in numbers of the regular force, Army has developed permanent schoolhouses to educate its officers and soldiers, and has professionalised training across the organisation as a whole. From Major-General Hutton opening federated schools of instruction in 1902 to the founding of a centralised training depot in 1921 and the establishment of permanent schools in 1943, the Army has been seeking to standardise training, improve technical proficiency, test individuals’ mettle, and reinforce a culture of continued learning for well over a century. The previous section established the value in this approach to knowledge management. The outcome of this progression is a highly skilled and educated professional military force that maintains high levels of preparedness to respond to crises, both domestically and overseas.

| Permanent | Reserve (Militia) | Total Force | Australian Population | Total Force as a % of Population | |

| 1914 | 2,989 | 42,656 | 45,645 | 4,940,952 | 0.92% |

| 1938 | 2,795 | 42,895 | 45,690 | 6,629,839 | 0.68% |

| 2021 | 29,631 | 19,673 | 49,304 | 25,739,256 | 0.19% |

| Change over time | +891.3% | -53.8% | +8% | +420.9% | -79.3% |

Source: Compiled by the author. Data for 1914 and 1938 was drawn from the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, Year Book Australia, 1915[106] and Year Book Australia, 1939.[107] Data for 2021 was drawn from the Department of Defence’s 2020–21 annual report[108] and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.[109]

The data presented in Table 1 is significant as it indicates that, as of 2021, Army has an absolute numerical advantage in permanent professional military personnel compared to the situations that existed when it mobilised for the First and Second World Wars. The significance of this advantage cannot be understated. For example, as of 2021 the Army had 5,715 officers within the permanent force.[110] Of these, approximately 60 personnel hold the rank of Brigadier (one star). While most of these senior officers hold staff appointments across various senior headquarters rather than command appointments, the fact that Army maintains these appointments on the order of battle demonstrates the depth of experience that it currently retains. Many of these brigadiers would undoubtedly have the professional military experience and qualifications to command a brigade in various specialisations ranging from combat to combat support and combat service support if they were called upon to do so. These personnel will have, over their careers, progressed through multiple schoolhouses with a focus on professional mastery, command and management.

To understand the residual power presently held at star-rank level within the Australian Army, it is worthwhile making a direct comparison with historical experience. In 1918, for example, the officer corps of the AIF had 31 brigadiers serving across command and staff appointments (20 militia, five permanent, six British and one from New Zealand).[111] To achieve this scale, however, the AIF had needed to significantly expand and to promote officers (from both the permanent and militia forces). By contrast, the current Australian Army could, if it chose to, reapportion 31 brigadiers from within its current organisational structure to support the mobilisation of combat and combat support formations. While this example is extreme and simplistic in nature, it does reveal the significance of increasing the size of the force over the last 100 years, and the depth of professional military leadership that currently resides within Army. It should also be highlighted that this depth of experience would expand if the reserve forces of the Army were to be included.[112]

The example provided underscores that Army’s edge is enhanced by having access to a large body of trained and experienced personnel across the permanent, reserve and ex-serving categories. The flexibility that this intellectual edge affords Army is incredibly valuable. In regard to officers, for example, while many may currently be employed within headquarters performing staff appointments in a garrison environment, these personnel could be re-tasked to fill important command and staff appointments in the field force during a mobilisation event. Many of these officers will have already held commands at the platoon, company and possibly battalion levels, and will have participated in a wide range of exercises and operational deployments over their careers. They will also have progressed through a formalised system of education that has provided them with a solid baseline of knowledge and aptitude. While some of these star-rank officers may not have served in line units for an extended period, their resident knowledge of military tactics, techniques and procedures makes them a highly valuable resource. The fact that they are already included on the order of battle reduces the need to rapidly train others to fill emerging gaps. This means that their mobilisation (if required) would provide Army with sufficient time to prepare another echelon for service—which would almost certainly include individuals with no previous military experience or training.

Having a formalised system of education and associated infrastructure is not the only marker that assists militaries in finding an asymmetric advantage.[113] It is also informative to understand how long a member has had to progress through the knowledge management cycle and thereby hone their skills. A report published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in 2019 concluded that, for ADF members who served between 1985 and 2019, the average length of service was 10 years.[114] This represents a significant investment by individuals into a professional military career where technical proficiency and field experimentation are highly valued during formative years of service. Knowing the level of professional mastery that individuals have achieved assists Army to wield asymmetric advantage against an opponent. In particular, a member of the Army, who has undergone 10 years of training is likely to outperform anyone who has only received limited training under, for example, a conscription model. The underlying assumption here is that the longer time an individual has available to train and to learn their profession, the better their performance will be. Further evidence for this viewpoint can be found in Ukraine’s thus-far successful (beyond any previous assessment or hope) defence against the Russian invasion. Since 2016, the Security Assistance Training Management Organization (SATMO), led by the United States, has embedded trainers within the Ukrainian military to educate them on NATO standard doctrine and operations.[115] Given Ukraine’s military achievements to this point, this investment in training appears to have involved an incredibly effective transfer of knowledge. Indeed, it has been so effective that Ukraine has been able to retain an asymmetric advantage over Russia, despite its relative disadvantages in size.[116]

In Australia, Army has adopted an asymmetric approach to warfare to alleviate the burden of its small size compared to other regional militaries. Critics (and some policymakers) have claimed that, should Army need to mobilise, the small numbers of professionally trained individuals will not be enough to enable even the raising of a division (as was accomplished during both world wars).[117] However, basing an assessment on only the number of current serving Army members is narrow-sighted. Individuals with a professional working knowledge of the military can be found in the reserves and also outside the organisation. Despite not serving Army in a full-time capacity, an individual with an average of 10 years’ military service could effectively support a mobilisation event and further reinforce Army’s ability to generate a force capable of achieving the government’s direction.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics holds a range of informative data on the ADF that demonstrates the scale of human resources contained among the members of the Australian population who have previous ADF service. Table 2 demonstrates that, as of 2021, there are 233,996 individuals with previous ADF service living in Australia. These people represent a major potential resource for the ADF during a mobilisation event, though of course there are numerous caveats.

| Age | Male (count) | Female (count) | Total (count) |

| 15–24 | 3,501 | 1,238 | 4,735 |

| 25–34 | 22,133 | 4,310 | 26,411 |

| 35–44 | 34,324 | 7,583 | 41,909 |

| 45–54 | 56,384 | 14,290 | 70,673 |

| 55–64 | 72,773 | 16,492 | 89,268 |

| Total | 233,996 | ||

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics.[118]

Unlocking the Potential of Previous Service

The raw data presented at Table 2 requires further breakdown to be of real utility in assessing the potential military capability available among members of the Australian population who have previous service but are not currently members of the ADF. Firstly, the numbers in Table 2 represent service in the ADF as a whole; they are not broken down by service (Navy / Army / Air Force). Given that the Army represents roughly 50 per cent of the ADF’s total workforce, however, it could be assumed that approximately 116,000 of the people captured in Table 2 have seen service in Army. This assumption is significant in assessing Army’s ability to retain an asymmetric advantage over an adversary during mobilisation. To illustrate this point, consider that in both the First World War and the Second World War the Australian Government mobilised a division of roughly 20,000 personnel within the first eight to 12 weeks of war and mobilised a further two to three divisions within the next 12 months. In both wars, these follow-on divisions were largely made up of raw recruits who required extensive training to become combat ready. Conversely, the Army of the 2020s has one permanent division and one reserve division, neither of which operates under the restrictions on overseas service that were experienced during the First and Second World Wars.

Based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there would appear to be approximately 70,000 people aged 25 to 54 with previous military service. This is a sufficient personnel resource for Army to field three additional divisions. It is acknowledged that this assessment does not account for issues such as medical restrictions, the rate at which individuals might volunteer for service, or the gaps their service might create within the civilian workforce. What the figures do demonstrate, however, is it that there exists significant capacity outside of the ADF’s permanent and reserve forces to achieve mobilisation of the Army beyond its current force structure. Leveraging previous military service, Army could rapidly raise units with members holding recognised training proficiencies and with relevant military experience. In addition to supporting Army to find and maintain asymmetric advantage, this personnel capability would have further benefits. Specifically, it would give the Australian Government and the ADF sufficient time to mobilise the economy and potentially train additional follow-on forces who have no military experience—raw recruits.