- Home

- Library

- Occasional Papers

- Drawing on Reserves

Drawing on Reserves

Assessing Civilian Employer/Manager Support for Employees’ Part-time Military Service

This Occasional Paper derives from a 2023 Australian Army Research Scheme funded project seeking to better understand the relationship between civilian employers and the part-time military careers of members of the Australian Army Reserve. Currently there are few empirical studies of Australian Defence Force (ADF) reservists. When the recruitment and retention of ADF reservists have been examined, the focus has been on their conditions of service, such as formal benefits and entitlements. With reservists increasingly being seen as a solution to current Defence workforce challenges, there is an urgent need for new evidence about how reserve service is affected by the state of civilian-military relations. This paper specifically addresses this issue by analysing how civilian employers support (or not) their workers to undertake reserve service. This is an important topic. At a micro level, support determines whether individual reservists are able maintain a part-time career in the armed forces. From a macro perspective, it directly affects the viability of Defence policy directions to increase utilisation and expansion of reserve forces.

Two key questions guided this research:

- What civilian workplace level challenges do reservists in the Australian Army face when balancing their military and civilian career responsibilities?

- How do civilian employers/managers, across a range of sectors, organisation sizes and demographics, currently view and facilitate (or otherwise) the participation of their employees in the Australian Army Reserves?

Answering these questions entailed two complementary but separate modes of data collection:

- Focus group interviews with 60 Army reservists based at three different and purposefully selected Australian locations.

- A nationwide survey of 800 civilian employers/managers, capturing their views about the inclusion and treatment of Army reservists within their organisation, with the ability to compare results from organisations of different sizes and in different sectors.

The three key findings of the study and accompanying recommendations are listed below. The results and their relevance for the nature of civilian-military relations in Australia should inform the government’s direction in the Defence Strategic Review (2023) (DSR) that Defence “investigate innovative ways to adapt the structure, shape and role of the Reserves”, and subsequent policy development.

Key Findings and Recommendations

Finding 1: Australian Army reservists requesting Defence leave frequently experience hostility, sanctions and discrimination in their civilian workplaces. This animosity generally stems from capacity issues and, in larger organisations, the unsupportive practices of middle managers.

Recommendation 1: Further encourage voluntary adherence to the Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act, by diversifying the current engagement with industry leaders through campaigns that seek to raise awareness and understanding of the Act amongst small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and middle managers.

Finding 2: Civilian employers/managers have limited appreciation for the transferability of skills attained through reserve service. This factor, coupled with the short notice that reservists are often provided to attend ADF courses, creates or exacerbates workplace conflict.

Recommendation 2: Industry-reservist relations would significantly benefit from reservists being provided with greater human resources (HR) support from the Department of Defence. This observation specifically relates to the provision of increased certainty and notice regarding the scheduling of training courses, and enhanced communication with employers/managers to promote the benefit of trained skills to civilian workplaces.

Finding 3: A belief that the military is intrinsically important significantly increases employer/manager support for their employees’ part-time military service. It is also a critical motivator for reservists to continue their military service in the face of workplace obstacles and disincentives.

Recommendation 3: The Australian government should increase its efforts and modernise its approach to fostering understanding between the Australian public and the ADF. This should include recognising that reservists are integral to national security and are motivated primarily by a volunteer ethic rather than the pursuit of career or financial rewards.

Rationale and outline of the study

Over the past decade there has been an increasing recognition among Western nations of the importance of Army reservists for the delivery of military capability. This development has seen greater utilisation of individual reservists and reserve units in deployments to major conflict zones and on humanitarian operations. The ADF Reserves has become an important factor in Defence workforce planning, seen as a way to: a) address current and expected future labour shortages in all-volunteer militaries as a consequence of a growing civil-military gap;[i] b) increase the strategic depth of the Army in order to mobilise for the return of Great Power competition, particularly in light of a general lack of community support for compulsory national service or other forms of conscription;[ii] c) fill important human capability gaps, such as in the cyber and information warfare domain, associated with the changing nature of conflict.[iii]

Despite this strategic positioning, and the Australian Army Reserve making up nearly a third (12,706) of the number of permanent members in the Australian Army (29,968),[iv] there is a dearth of available data and little consistent policy attention on the reserve forces. Mark Armstrong,[v] for example, has argued that the current strategic prominence of the reserves in Australia has largely been the outcome of their successful but ad hoc utilisation since the end of the Cold War rather than the result of clear strategic policy direction. Over the past decade, the limited strategic attention that has been paid to ADF reserves has largely focussed on ways to integrate reservists into the total ADF workforce, rather than considering who are reservists and what are their distinctive characteristics and identities.[vi]

Australia is not alone in this neglect, with studies in the field of armed forces and society[vii] being overwhelmingly related to permanent forces. This reticence is due largely to the connection of reservists to the citizen-soldier model of service from which contemporary military professionalism has sought to distinguish itself since the mid-century twentieth century. However, as recent significant international studies of the reserves emphasise,[viii] effective reserve policy requires an appreciation of – and a willingness to – develop empirical insights into the difficulties that reservists face in balancing military and civilian careers, and the ways they are subject to Defence systems that are designed for (and frequently privilege) regular members whose service is mostly their main ongoing job, and full-time in nature. In contrast, Reserves service is normally part-time in nature.

With the ADF currently having trouble achieving its desired workforce level,[ix] and with an increased appreciation for the immediate need for mobilisation planning (though currently with only moderate planned increases in the Defence budget), it is important for Defence to better comprehend the reserve workforce. As the military sociologist and former advisor to the US Chiefs of Staff, Charles Moskos, noted in his foundational three-part study of the US reserves, it is important for the reserves to be analytically conceptualised as being “more than just an organisational variation of active components”.[x] This appreciation is most urgently required for the DSR recommendation, subsequently accepted by the Federal Government, to undertake “A comprehensive strategic review of the ADF Reserves, including consideration of the reintroduction of a Ready Reserve Scheme…” by 2025.

This paper reports results from empirical research that focusses on the relations between Australian Army reservists and their civilian employers. Focus topics include issues relating to Defence leave and other matters relevant to reservists’ capacity to balance their civilian and military careers.

The Australian Army currently constitutes nearly three quarters (73%) of the total ADF reserve force (Defence Census 2019). Significantly, a key feature of the Ready Reserve Scheme, which operated from 1991 to 1996, was that reservists in this scheme undertook twelve months full-time training similar to personnel recruited for full-time permanent service.[xi] Such a long period of consolidated military service would require a reservist to take a significant period of leave from study or any concurrent civilian employment.

The study was guided by two specific research questions:

- What civilian workplace level challenges do members of the Reserve in the Australian Army face when balancing their military and civilian career responsibilities?

- How do civilian employers/managers, across a range of sectors, organisation sizes and demographics currently view and facilitate (or otherwise) the participation of their employees in the Australian Army Reserves?

The research focus of this paper is similar to the ‘Keeping Enough in Reserve’ (2018) study undertaken in 2018 by the UK’s Future Reserves Research Programme. This was a sociology focussed research project co-funded by the British Army, Ministry of Defence and Economic and Social Research Council to inform the implementation of the UK Ministry of Defence Future Reserves 2020 programme (FR2020). FR2020 was a strategy to substantially increase the number and role of the reserves in the UK armed forces, providing it with generalist additional workforce capacity as well as expertise in areas considered not to be practical or cost effective to maintain as part of the regular forces. Like our study, the ‘Keeping Enough in Reserve’ project[xii] recognised that the nature and extent of employer support for current (and potential) reservists can markedly influence the viability of policy initiatives aimed at increasing either the number of reservists or the intensity of the service demands placed on them by the military. Our analysis differs methodologically from ‘Keeping Enough in Reserve’ in that we adopted a mixed-method approach, combining qualitative and quantitative insights, whereas the UK study was primarily based on interviews with reservists.[xiii]

Specifically, our study’s two research questions were answered by two separate but complementary modes of data collection:

- Focus group interviews with 60 Army reservists based at three different and purposefully selected Australian locations.

- A nationwide survey of 800 civilian employers/managers, capturing their views about the inclusion and treatment of Army reservists within their organisation, with the ability to compare results from organisations of different sizes and within different sectors.

Endnotes

[i] Raphael S Cohen. Demystifying the citizen soldier. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, 2015; Thomas S Szayna. The civil-military gap in the United States: Does it exist, why, and does it matter?. Vol. 379. Rand Corporation, 2007.

[ii] Elbridge A. Colby and A. Wess Mitchell. ‘The Age of Great-Power Competition: How the Trump Administration Refashioned American Strategy’. Foreign Affairs 99(1), 2020: 118-130; Stephen K Trynosky. Paper TigIRR: The Army’s Diminished Strategic Personnel Reserve in an Era of Great Power Competition. Technical Report U.S. Army War College. 2023. Accessed at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/trecms/AD1215164

[iii] Stephen Dalzell, Molly Dunigan, Phillip Carter, Katherine Costello, Amy Grace Donohue, Brian Phillips, Michael Pollard, Susan A. Resetar, Michael Shurkin. Manpower Alternatives to Enhance Total Force Capabilities: Could New Forms of Reserve Service Help Alleviate Military Shortfalls? Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2019; Isaac R. Porche III, Caolionn O’Connell, John S. Davis II, Bradley Wilson, Chad C. Serena, Tracy C. McCausland, Erin-Elizabeth Johnson, Brian D. Wisniewski, Michael Vasseur. Cyber Power Potential of the Army's Reserve Component. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017.

[iv] Defence Census 2019: Public Report. Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. Accessed at https://www.contactairlandandsea.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/defence…

[v] Mark Armstrong. ‘Pursuing the Total Force: Strategic Guidance for the Australian Defence Force Reserves in Defence White Papers since 1976’. Security Challenges 16(2), 2020: 71–87.

[vi] Samantha Crompvoets. Exploring Future Service Needs of Australian Defence Force Reservists. Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Canberra, 2013; Brad West. ‘The future of reserves: In search of a social research agenda for implementing the Total Workforce Model’. Australian Army Journal 14(1), 2018: 109–119.

[vii] James Burk, Robert J. Waldman, David R. Segal, and Charles C. Moskos. The military in new times: Adapting armed forces to a turbulent world. New York: Routledge, 2019.

[viii] Eyal Ben-Ari and Vincent Connelly (eds.) Contemporary military reserves: Between the civilian and military worlds. New York: Routledge, 2022; Patrick Bury ‘The Changing Nature of Reserve Cohesion: A Study of Future Reserves 2020 and British Army Reserve Logistic Units’. Armed Forces & Society 45(2), 2019: 310-332; Nir Gazit, Edna Lomsky-Feder and Eyal Ben Ari. ‘Military Covenants and Contracts in Motion: Reservists as Transmigrants 10 Years Later’. Armed Forces & Society 47(4), 2021: 616–634; K. Neil Jenkings, Antonia Dawes, Tim Edmunds, Paul Higate and Rachel Woodward. ‘Reserve forces and the privatization of the military by the nation state’. In O. Swed and T. Crosbie (eds) The sociology of privatized security. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019: 107-136.

[ix] Parliament of Australia Inquiry into the Department of Defence Annual Report 2021–22. Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. Accessed at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_…

[x] Charles C. Moskos. The Sociology of Army Reserves: An Organizational Assessment. United States Army Research Institute for Behavioral and Social Science. ARI Research Note, 1990, p86.

[xi] Hugh Smith and Nick Jans, N. ‘Use Them or Lose Them? Australia’s Defence Force Reserves’. Armed Forces and Society 37(2), 2011: 301-320.

[xii] Timothy Edmunds, Antonia Dawes, Paul Higate, K. Neil Jenkings and Rachel Woodward. ‘Reserve forces and the transformation of British military organisation: soldiers, citizens and society.’ Defence Studies 16(2), 2016: 118-136.

[xiii]Paul Higate, Antonia Dawes, Tim Edmunds, K. Neil Jenkings, and Rachel Woodward. ‘Militarization, stigma, and resistance: negotiating military reservist identity in the civilian workplace’. Critical Military Studies 7(2), 2021: 173–191.

[xiv] Gazit et al. 2021

[xvi] https://www.reserveemployersupport.gov.au/ Last accessed 30 August 2024

[xvii] Geoffrey J Orme and E James Kehoe. ‘Left behind but not left out?: Perceptions of support for family members of deployed reservists’. Australian Defence Force Journal. 185, 2011: 26-33.

[xviii] For example, Mladen Adamovic and Andreas Leibbrandt. ‘A large‐scale field experiment on occupational gender segregation and hiring discrimination’. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 62(1), 2023: 34-59; Mladen Adamovic and Andreas Leibbrandt. ‘Is there a glass ceiling for ethnic minorities to enter leadership positions? Evidence from a field experiment with over 12,000 job applications’. The Leadership Quarterly. 34(2), 2023: 1–13.

[xix] Lauren A. Rivera, ‘Employer decision making’. Annual review of sociology. 46(1), 2020: 215-232.

[xx] Ibid; Lyn Spillman and Sorcha A. Brophy. ‘Professionalism as a cultural form: Knowledge, craft, and moral agency’. Journal of Professions and Organization 5(2), 2018: 155-166.

Mixed Methods

As indicated in the introduction, our research questions were answered utilising a mixed method approach, combining (a) qualitative focus group interviews of reservists with (b) a quantitative survey of employers/managers. This approach aims to use different forms of data in a single study to investigate the same phenomenon. The rationale is that having more than one form of data allows researchers to attain comprehensive answers to research questions. In this study, it helps to uncover the intersection between everyday experiences of reservists in various workplaces and employer attitudes and dispositions in relation to the support they are able and willing to provide to their employees who pursue a part-time military career.

Methodological Assumptions and Hypotheses

By utilising two different forms of data, the mixed method approach attempts to avoid certain blind spots that are associated with a single research method. However, any study inevitably privileges certain comprehensions of the world over others. In the interests of validity and transparency, it is important to declare how the chosen research design may prioritise certain concerns. This research project is structured by two such methodological assumptions:

1) The Australian Army Reserves needs to be comprehended culturally in its own terms, and not as a derivation or variant of the permanent forces.[xxi] Reserve service in Australia is distinctively shaped by a particular history and by institutional policies that give the term ‘reserve service’ a distinct meaning.[xxii]

2) Participation in the Australian Army Reserves is influenced by a civilian-military relationship that is distinctively Australian.[xxiii] This means that we need to measure how influence may relate both to rational economic interests and to cultural understandings of military service when considering the degree to which employer actions support (or not) reservists’ service.

To determine how business capacity and economic interests intersect with cultural factors, the two research methods test the following three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The larger the company, the greater the level of support civilian employers/managers demonstrate in employing and supporting members of the Australian Army Reserves.

Hypothesis 2: Stigma levels related to the employment and support provided to members of the Australian Army Reserves differ across industries in ways that reflect how different sectors intersect economically and culturally with Defence.

Hypothesis 3: The level of civilian workplace support to members of the Australian Army Reserve differs in relation to the perceptions that civilian employers/managers have of military service and the views they believe are held by their civilian employees.

Focus Groups

For the purposes of this study, the sample of Australian Army reservists is limited to those members who are service category (SERCAT) 5 and who hold civilian employment. SERCAT 5 encompasses the majority of reservists. They serve in a part time capacity, providing regular service to a unit. This contrasts with reservists in other SERCATs, where work is typically more irregular and may be used to fill specialist short term gaps in the regular ADF workforce. The focus group methodology garnered qualitative data from a group discussion. This method ensured that different perspectives on a single topic were attained while identifying areas where people tended to have a shared understanding.

Six focus groups were carried out in late 2023 and early 2024 with members of the Australian Army Reserves across three locations: Gallipoli Barracks in Brisbane, Holsworthy Barracks in Sydney, and Lavarack Barracks in Townsville. These research sites were selected based on 2021 Australian Bureau of Statistics Census data showing that over 50% of current ADF reservists (56% or 47,700 people) live in either New South Wales or Queensland, with around two-thirds (67%) living in a greater capital city. Townsville is a garrison town in regional Australia and was selected to comprehend the diversity among Australian Army reservists. Notably there are plans to increase the number of soldiers located in Townsville to give effect to the DSR direction that the military workforce is "optimised for littoral manoeuvre operations by sea, land and air from Australia, with enhanced long-range fires". According to the census, 565 people from Townsville are in the ADF Reserves, higher than any other regional area.

In total, 60 reservists participated in the focus groups, with two sessions being held at each location on a single night. All focus groups were carried out on a Tuesday night when reservists were attending barracks for their routine parade schedule. The focus groups sought to elicit responses that were naturalistic. By this we mean that questions and subsequent prompts were used in ways to encourage responses in a manner similar to normal, everyday communication. The focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed, with the resulting data then subject to thematic analysis. In presenting the focus group results, we utilise direct quotations both as a measure of validity for our analytic claims and as a compelling way of conveying reservists’ experiences in their own words.

The focus groups revolved around the interview questions outlined below in Box 1. The methodology allowed for follow-up questions to issues and themes that emerged from responses and discussion in the group.

|

Box 1: Main questions for focus group interviews of Australian Army Reservists Q1. What is the experience of being an Army Reservist in a civilian workplace and what is it like balancing your civilian career with being part-time in the ADF?

Q2. What are your employer’s/manager’s attitudes and dispositions to you being a Reservist and pursuing a military career part-time?

Q3. How do your workmates react to knowledge of your Army service and how willing are you to share with them your military identity and role?

Q4. Have you experienced difficulty in requesting leave for training or deployments from your place of civilian employment?

Q5. Do you think that the skills attained in your Reservist service are transferable to your civilian career?

Q6. To what extent does your civilian employer/manager appreciate a transferability of skills and knowledge between your military experience and your civilian workplace?

Q7. Are the reactions to your military service in the workplace similar to those you experience in the community broadly?

Q8. What do you believe explains the support or lack of support for your military service in your particular workplace?

Q9. How critical is support from your civilian employer/manager to the extent to which you are able to pursue a part-time career in the Army and/or remain in the Army Reserve?

Q10. Do you have any final comments on issues that have been raised in the session or on topics that have not been covered but which you consider significant to the aims of the project?

|

Employer/Manager Survey

Our employer survey elicited attitudinal measures of employer practices and dispositions regarding their employees’ reserve service. While there is prevalent survey research in the United States examining civilian-military relations,[xxiv] in Australia there is a dearth of existing quantitative insight into such civilian-military relations.[xxv] It is unclear to what extent a ‘supporting the troops’ sentiment might underpin the decisions of employers and managers in relation to hiring individuals who are reservists or supporting their rights to undertake part-time military service. There is nevertheless opinion poll data in Australia that consistently finds positive public regard for the armed forces.[xxvi] Notwithstanding the existence of such poll results, there remains little data to suggest a deep level of public understanding about the armed forces and the work of military personnel.[xxvii] In the absence of any strong quantitative studies, critical analysis has typically presumed that the organisational culture of industry is one that is supportive of the military.[xxviii]

For the purposes of this study, civilian employers are defined as people who do – or could potentially – recruit or manage members of the Australian Army Reserves in civilian employment. The sample was restricted to those who have responsibility for employed individuals and may potentially have recruitment responsibilities in their current job. By focusing on potential rather than actual employers of reservists, the survey measures how capacity issues (Hypothesis 1) as well as orientations toward Defence (Hypothesis 2 & 3) are likely to influence the support and general employment prospects of Australian Army reservists in civilian workplaces.

Civilian employers in Australia were sourced from established volunteer panels maintained by our field partner, Wallis Social Research. Invitations and information about the study were sent to eligible panel members and responses were screened and managed to ensure a final sample with the desired composition and coverage (i.e., a mix of industry and organisational size categories proportional to known workforce parameters). The resulting nationwide employer sample contains 820 full responses. This data is the basis for the quantitative findings in this paper.

The core of our employer survey is a set of 12 questions that elicited scale-based numerical responses to a set of attitudinal propositions (see details below). Another two questions gathered information about the employer/manager’s organisation (its industry and size). Finally, four questions sought information about demographic attributes of the respondents themselves: their age, level of highest educational attainment, gender, and cultural identity. The survey data was analysed using the standard statistical software package, STATA, to produce the descriptive summary results and graphs presented later in this paper.

A list of our 12 attitudinal questions is provided in Box 2. In generating these questions, we followed and extended the earlier respected work of Meredith Kleykamp on civilian-military relations.[xxix] This work applied a vignette approach to measure respondents’ attitudinal support for and/or stigma towards Australian Army reservists. Specifically, respondents were randomly presented with one of two short vignettes about a hypothetical reservist, John, to assess their views. The two vignettes introduced a comparative element to the data, with ‘John’ having a trade qualification in one scenario and a university degree in the other.

The vignette text reads as follows:

“John is a single, 30-year-old man with a [trade qualification / university degree]. For the past 10 years, he maintained steady civilian employment while also serving as a Reservist in the Army. During that time, he took 6 months off work to be deployed to Afghanistan. He has also taken shorter periods of leave for training and to be part of ADF responses to natural disasters and Covid-19.”

|

Box 2: Main attitudinal questions in the civilian employer survey Q1. How likely is it that your organisation would be supportive of John taking leave for training and foreign deployments to combat zones?

Q2. What capacity would your organisation have to provide John with leave for training and foreign deployments to combat zones?

Q3. Do you think that recent labour market challenges in the Australian economy have reduced the likelihood that your organisation would be supportive of John taking leave for training and foreign deployments to combat zones?

Q4. How would you think employees in your organization would feel about John being someone who they would work closely with on a daily basis?

Q5. If John and an equally qualified candidate were being considered for an internally advertised position in your organisation, how much preferential treatment might John be given based on his military service?

Q6. How relevant do you think John’s military training and experience would be for his role as an employee in your organisation?

Q7. How likely do you think it is that John is a ‘hard worker’?

Q8. How likely do you think it is that John is a creative problem solver able to ‘think outside of the box’?

Q9. How likely would you think it is that John was receiving regular treatment for a mental health problem?

Q10. How many Reservists or recent military veterans do you believe are employed in your organisation?

Q11. How would you rate the political orientation of most employees in your organisation?

Q12. Do you think that Australian governments should spend more or spend less on the military?

|

Survey Questions 1, 2 and 3 seek to determine the organisation’s perceived levels of support and capacity to provide leave for a hypothetical reservist. These questions directly address issues relating to: a) how civilian employers support (or not) employees who are members of the Australian Army Reserves; b) what attempts to increase recruitment, retention and mobilisation of reservists will likely mean for the Australian Army, reservists, and civilian employers; and c) how support and capacity issues may have changed due to recent economic and labour market circumstances.

Other questions in the survey addressed how this level of support and capacity may be influenced by civilian employers’ perceptions of the ADF and their beliefs about the views held by their civilian employees (Hypotheses 2 and 3). Support is measured by questions relating to: a) beliefs about how employees in the company would likely feel about a hypothetical Australian Army reservist being someone who they would work closely with on a daily basis (Question 4) and how much preference this person might attain for an internally advertised position, relative to other similarly qualified candidates, on the basis of their military service (Question 5).

To gauge how perceptions about reservists might be influenced by the ideological orientations towards the ADF of civilian employers themselves, or of their employees, the survey includes established and widely used questions about perceived political orientation (Question 11) and beliefs about military spending (Question 12).

Four questions addressed the topic of whether stigma exists around the institutional characteristics of military service and the applicability of military service skills to civilian employment. Question 6 considers the perceived relevance of military training and skills to civilian employment. Questions 7 and 8 measure whether the hypothetical reservist is perceived as a ‘hard worker’ compared with a ‘creative problem solver’. Question 9 addresses whether the respondent thinks that the hypothetical reservist is likely to be receiving regular treatment for a mental health problem.

The vignette used in our survey invokes a male protagonist, ‘John’. This formulation was chosen in part because 80 per cent of Army reservists are men. In past research on stigmatisation in military to civilian transitions, it has also been found that men are more likely to be defined by others with reference to the institutional nature of military service and issues around mental health. No ethnicity is assigned to the vignette’s protagonist due to limitations of the sample size and the relatively low levels of diversity on this characteristic within the ADF: 87% of ADF members were born in Australia and 73% have Australian ancestry. One benefit of the vignette approach is that it can be built upon by future researchers, who could generate further insights by having, for instance, protagonists of different genders and ethnicities.

Endnotes

[xxi] Moskos 1990

[xxii]Smith and Jans 2011

[xxiii] Brad West and Cate Carter. ‘Antipodean Insights into Civil–Military Relations’. In B. West and C. Carter (eds) The New Australian Military Sociology: Antipodean Perspectives. New York: Berghahn, 2024: 1-28.

[xxiv] For example, Alair MacLean and Meredith Kleykamp. ‘Coming home: Attitudes toward US veterans returning from Iraq’. Social Problems 61(1), 2014: 131-154.

[xxv] Mick Ryan, Duncan Lewis, Risa Brooks, Cameron Moore, Michael Evans, Brendan Sargeant, Steven Day, Pauline Collins and Dan Bourchier. Civil-military relations in Australia: past, present and future. 2021. Accessed at https://www.defence.gov.au/defence-activities/research-innovation/research-publications/civil-military-relations-australia-past-present-and-future; Ben Wadham and Willem de Lint. ‘Australia: Expanding and Applying the Field of Civil-Military Relations’. In W. R. Thompson (Ed.) Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

[xxvi]ANU Poll 2021. Accessed at https://whataustraliathinks.org.au/data_story/democracy-safe-but-slipping/; Danielle Chubb and Ian McAllister. Australian Public Opinion, Defence and Foreign Policy: Attitudes and Trends Since 1945. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

[xxvii] Hines, Lindsey A., Rachael Gribble, Simon Wessely, Christopher Dandeker, and Nicola T. Fear. ‘Are the armed forces understood and supported by the public? A view from the United Kingdom’. Armed Forces & Society 41 (4), 2015: 688-713.

[xxviii] For example, Katharine M Millar. Support the troops: military obligation, gender, and the making of political community. Oxford University Press, 2022.

[xxix] Meredith Kleykamp, Crosby Hipes, and Alair MacLean. ‘Who supports US veterans and who exaggerates their support?’. Armed Forces & Society 44(1), 2018: 92-115.; MacLean and Kleykamp 2014.

Finding 1: Capacity issues as the basis for hostility, informal sanctions and discrimination

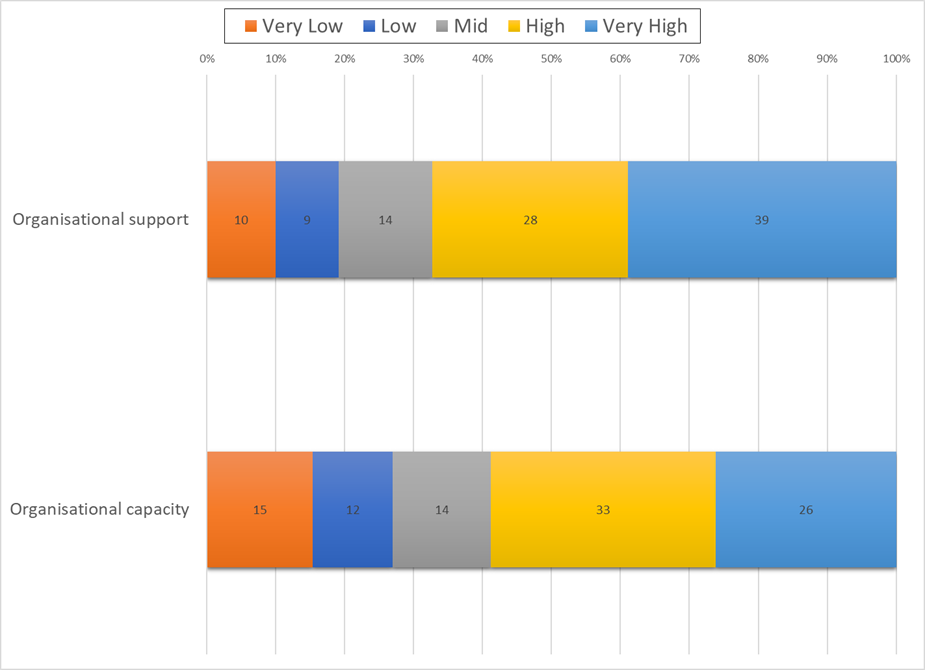

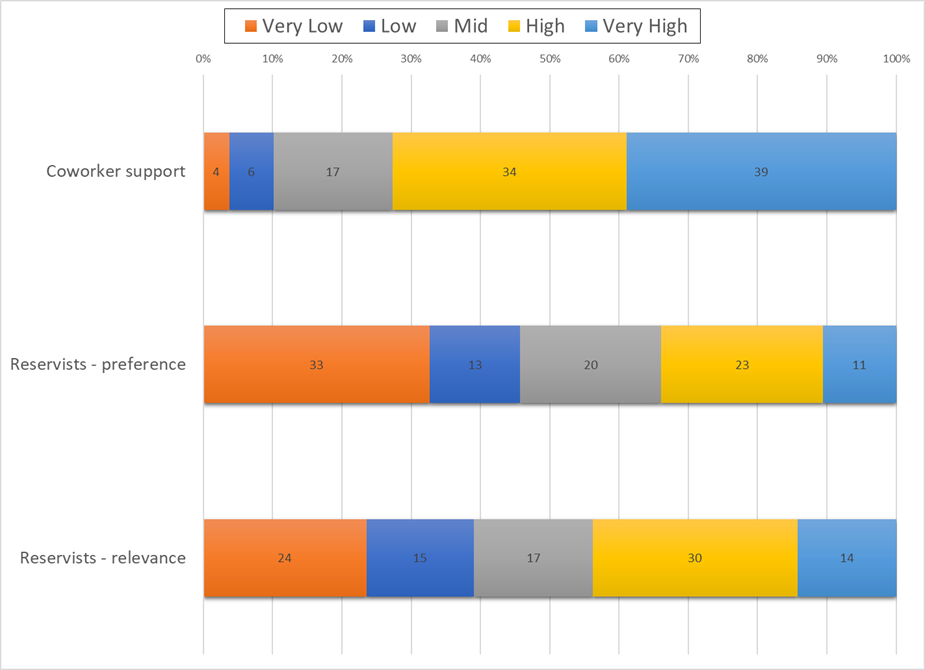

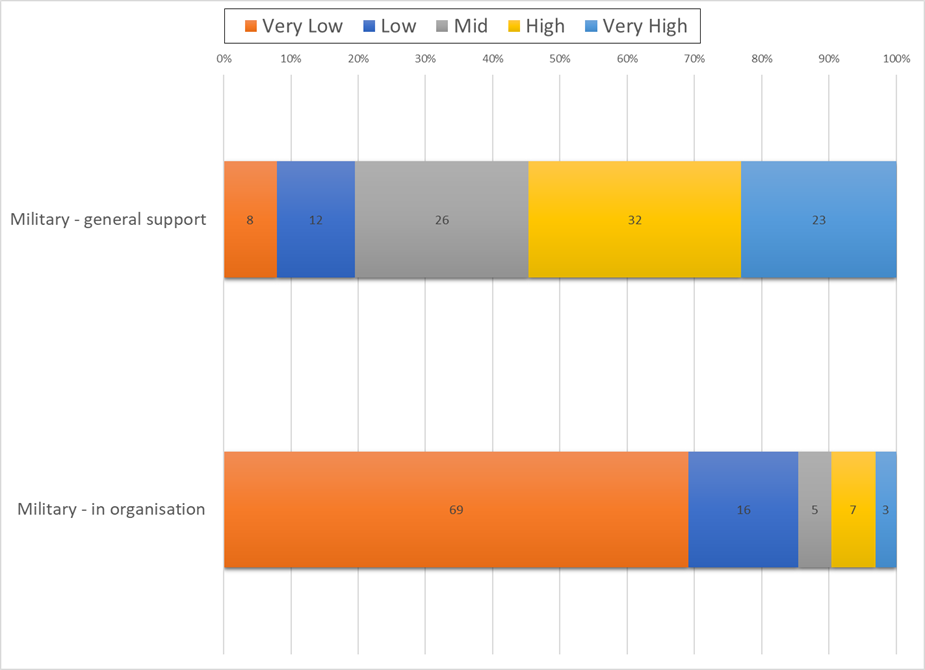

Australian Army reservists frequently experience hostility, informal sanctions and discrimination in their civilian workplaces when requesting reasonable periods of leave for military service. Our survey of civilian employers/managers clearly reveals the potential for such adverse treatment, with nearly one in five civilian employers (19%) indicating that their organisation would provide low or very low support to the hypothetical reservist John in taking leave for training and foreign deployments to combat zones (see Figure 1). While 2 in 3 civilian employers/managers (67%) indicated that their organisation is likely to provide John with a high or very high level of support, this finding must be seen in the context of other results (Question 2) that indicate a consistently lower level of organisational capacity to provide such leave (also Figure 1). Notably, 1 in 4 civilian employers/managers (27%) said their organisation’s capacity to provide leave to Reservist John would be low or very low.

These organisational capacity issues are consistent with our focus group results, in which participants experienced various degrees of difficulty in seeking leave to undertake Defence service and circumstances in which their reserve service resulted in them being disadvantaged for civilian career opportunities. As illustrated in the quote below, this includes acts that blatantly disregard the legislative rights of reservists.

I applied for a warehouse job and they said “you need full availability” and I said “Well I’m a Reservist” and they said “You’re not allowed to apply”. And I said “You know you’re breaking the Defence Reserve Protection Act by not letting me even go for a job interview”? And they said “No we will not hire anyone unless they have full availability”.

In most cases the discrimination and disadvantages that reservists experience are not as blatant, but requests for Defence leave commonly result in contestation around reservists’ rights and what is reasonable for periods of leave and prior notice.

In a high number of cases, reservists indicated that their employers had a generally low knowledge of the Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act. As a result, the reservists commonly had to educate their managers about their legal rights. This includes reservists often having to invoke the legislation themselves or to request a Defence representative to do so on their behalf to secure leave for Defence service, even when an appropriate period of notice was provided. The below quote is indicative of these experiences and the issues they present for reservists.

And then even when I had HR call me up about it, they told me I need to either be a soldier or a nurse. I had to make that decision, you need to make that decision whether you want to be a soldier or a nurse. So and then you’ve got to get your platoon commander to write them a nasty letter to say, listen this is the legislation, we’re going to come after you if you don’t let him [take leave].

In the focus group interviews, many respondents indicated that the legislative protection provided to reservists eventually compelled employers/managers to approve the specific instance of requested leave. However, this action did not permanently resolve, and in some cases exacerbated, tensions in the workplace around the right of the employee to pursue a part-time Army career. Reservists who had experienced tensions with their employers/mangers also reported that they had been subject to various sanctions as a consequence of taking leave for Reservist service. For example, as illustrated in the quotes below, this includes reservists suddenly being rostered with nightshifts or assigned to less fulfilling duties.

It irritated them that I had this trump card, where I was like, well this is the Federal Government you’ve got to let me go. So they resented that, and then they gave me 8 weeks of nightshift prior to acknowledging that they had to let me go. So at least how I interpreted it, and this is State Government.

There’s ways they can make your life difficult… all of a sudden, there’s these big jobs right, they start getting pushed into these bigger jobs and start to have to go, pick up the slack for all the shit jobs. It’s basically their way of punishing you for taking time off, it’s - there’s a lot of ways they can do it.

Most tensions in the workplace concern reservists either taking extended periods away from their civilian employment, or the length of notice that reservists provide ahead of their absence (a topic that will be further explored in Finding 2). Antagonism exists even where the ADF is engaged in major disaster response that affects public welfare and for which there is generally broad public support for military involvement. For example, many of the interviewed reservists who supported state emergency agencies during the 2020 Black Summer bushfires, declared that this mandatory call-out saw their employer/manager expressing concern about their Reservist service impacting upon their business operations.

In addition to concerns around extended absence from the workplace, many employer/managers are simply reluctant to provide flexible work hours. This reticence manifests in inflexible weekly rosters, restricting the dates reservists have booked for annual leave (which they intend to use for ADF service), and general expressions of concern about the perceived productivity of employees after their attendance at ADF training and exercises. Such attitudes significantly impact reservists’ ability to pursue part-time military careers.

They pretty much on a weekly basis they like to try to keep me to work late which I just have to say “Sorry it’s in my contract, no can do, Tuesday’s the 1 day I need to leave”. I’m happy to work overtime every other day of the week, work weekends but when I ask for a nice 4 o’clock finish on a Tuesday which is still pushing it with all the traffic from the area, it’s a big struggle. I missed out on 2 months coming to Tuesday nights because they ignored my roster and booked me on night shift. So I miss out on a lot of courses and a lot of training because of that.

I had 3 weeks, 4 weeks leave booked (for Reservist training course), unpaid due to the company not supplying pay for that sort of, that period of time. So I’d taken it out of my own time to sacrifice a month of pay and then during that booked time the company decided to send me on a 2 week course out of state, (stating that) pretty much I can’t back out of the course. So I stated the requirements and what it (the Defence course), that I’d already enrolled in this course and that it was it’s pretty much the 1 remaining course I need to tick a box in my (Army rank) position and they pretty much turned a blind eye, booked me on this (civilian work) course and said there’s nothing they can do about it.

In the context of such obstructive management practices, the focus group data found a correlation between those employers who were most supportive of reservists taking leave for training and deployments and those that generally followed good HR management practices and who broadly respected the legislative rights of workers. Organisations with well managed HR departments and functions are thus more likely to be responsive to and accommodating of reservists’ needs for workplace flexibility, independently of their views about the military.

It is notable that there was very little evidence that anti-military sentiment motivated discrimination against reservists by employer/managers. This observation was supported by our survey results, with employers/managers who support an increase in government military spending outnumbering those who prefer a decrease by nearly 3 to 1. Rather, employer unwillingness to provide Defence leave appears to be most often based in capacity considerations and associated profitability factors. As one reservist describes, “Look I think in general they (employers/managers) support Defence, the role of Defence and its importance, it’s really just the capability of their individuals, a bit of a – just not in my backyard.” However, as will be outlined in Finding 3, general dispositions and levels of support towards the ADF (such as a sentiment of ‘supporting the troops’) are also a determining factor in the degree to which reservists are likely to receive workplace level support for their military careers.

Our survey results further reinforce the conclusion that concerns with capacity issues and profitability are a major influence on the level of support available to reservists in civilian workplaces. We found that perceived capacity to support reservists is between 6 and 9 per cent higher in larger organisations with more than 20 employees, compared to small organisations with 20 or fewer employees. These differences are both statistically and materially significant, and they exist after adjusting for other sources of difference between firms; that is, these are ‘like-for-like’ comparisons.[xxx] As such, the data confirms Hypothesis 1 that ‘The larger the company the greater the level of support civilian employers/managers demonstrate in employing and supporting members of the Australian Army Reserve.’

This finding is noteworthy on two counts. First, it shows that, in relation to accommodating flexibility in employment, Defence leave for reservists does not significantly differ to existing workplace research that finds larger organisations are more likely than smaller ones to see a competitive advantage by pursuing Human Resource strategies that enable and accommodate some flexibility for employees.[xxxi] Second, the finding has significant implications for the development of Defence policy options that aim to increase the size of the Australian Army Reserve and to use reservists in ways to fill gaps in strategic areas such as cyber. Both strategies substantially rely on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which represent the overwhelming majority of all businesses and organisations in Australia, providing appropriate support to their employees undertaking reservist service. According to the OECD, SMEs made up over 99% of employing enterprises in Australia in 2021-22 (i.e., excluding sole proprietorships) and provided 66% of total employment.[xxxii] However, SMEs also have the least capacity to cover the absence of employees, due to their inherently limited workforce size.

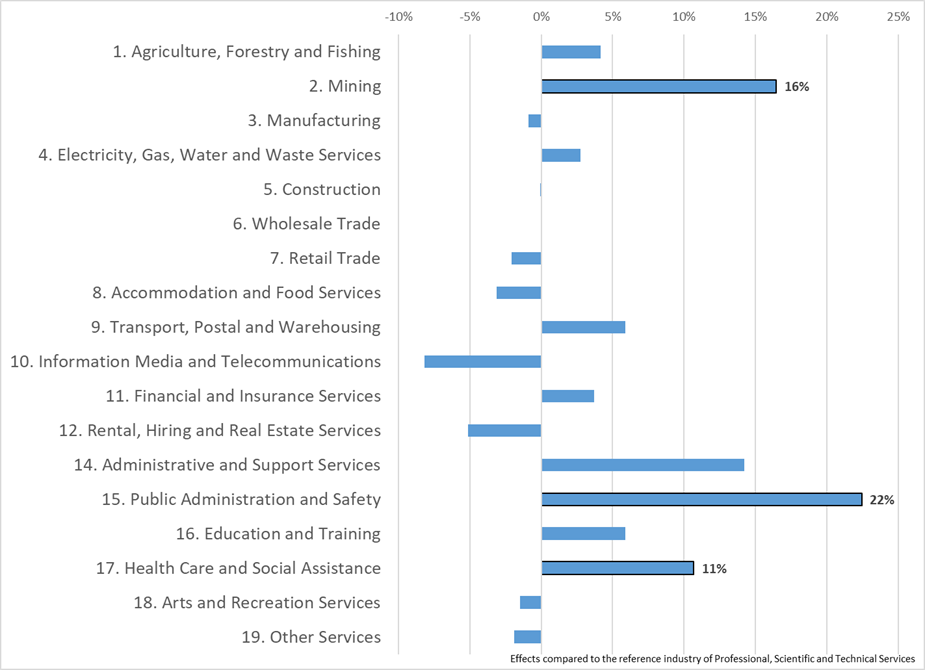

Beyond mere capacity factors, the survey reveals organisational support for reservists by employers/managers differs according to industry sector, even when all other factors (including organisation size) are constant. As outlined in Figure 2, certain industries report a significantly higher willingness and propensity to support reservists’ service. Most significantly, public administration, mining, and health care provide strong levels of support.

This survey finding is consistent with the focus group data. Numerous participants indicated that there were certain industry sectors more likely to be reservist friendly. As illustrated in the quotes below, certain sectors, such as public service, emergency services and the Defence industry, provide both institutional and cultural support for reservists. The probability of this support being available is much enhanced when other reservists are present in the workplace, particularly in management roles.

And other people from work (Police) who are in the Reserves, because so many people that they’re around are in, they, they also have a pretty positive view of people in the Reserves or people who are in the Defence.

… for someone working in Defence industry, having that previous Defence experience definitely does benefit a lot. Safe to say I’m pretty sure I got my role because of my experience being in the army and in the Army Reserves… they trust your ability to be able to distil information and provide it in a means that is required by the customer.

Our focus groups also revealed that the most supportive workplaces are typically those that employ other reservists. This factor helps raise awareness of both the legislative environment and the nature of reserve service. As illustrated in the quote below, familiarity with Defence leave requirements among managers (who themselves have military experience and who are willing to take on an advocacy role) places reservists in an especially advantageous position.

So I’ve told my manager and he’s been a previous Navy member so he’s completely on board with it. He vouches for me to the other staff members and stuff if they’re a bit unaware or uncertain what it entails. But he’s got my full support, and he advocates for that, so I’m in a pretty good position.

The survey results reinforce this point, with organisations on average displaying stronger support for reservists (and more favourable views about reservists’ capabilities) if the employer/manager indicated that they had more reservists on the payroll (Figure 3). To quantify this effect, we estimate that (all else being equal) the capacity of a workplace to support Defence leave would be 31 per cent higher for an organisation in which ‘almost all’ employees were reservists or were recent military veterans, compared to an (otherwise similar) organisation in which ‘none at all’ were in this category. Based on this result, we argue that Hypothesis 2 is broadly confirmed: ‘Stigma levels related to the employment and support provided to members of the Australian Army Reserves differ across industries in ways that reflect how different sectors intersect economically and culturally with Defence.’

While larger employers are on the whole more supportive of reservists undertaking Defence leave, the focus group data revealed that sometimes the high numbers of reservists in a workplace becomes the source of tension and is itself an initiator of discrimination (including instances of direct contestation to the Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act). Consider the example below, in which the reservist describes a coordinated HR strategy in his organisation to contest the rights of its employees to undertake military service.

Rosters … I quote to them the Defence Reserve Protection Act and they still fight on that… they’re under the impression that through guidance from industrial lawyers, that they will defend their rights to reject my Defence leave when required. They’re very tricky with their wording and stuff like. So they’ll tell me stuff over the phone, they won’t put it in writing. Anyway so they’re under pressure to not let people go to Defence… because there’s a lack of staff.

As such, we suggest that, while certain positions, workplaces and industries are more likely to provide support to reservists, requests for reasonable periods of leave for military service are a considerable source of tension in all organisations. Ultimately, the legislative protection provided to reservists is not widely appreciated by mainstream civilian employers/managers, let alone universally upheld.

One reason for the prevalence of tensions is that resistance to legislative compliance often stems from individual managers whose actions do not reflect the official policies of their organisation. Reservists employed in large organisations (whether in the private sector or government) commonly reported the significant role of middle management in contesting Defence leave, with this occurring largely irrespective of the organisation officially declaring itself a ‘supportive employer’ of reservists. This middle tier of management (commonly line managers) was often reported as seeing their role as separate from their organisation’s commitments to corporate social responsibility. Variance in the support for Defence leave in practice, across different levels of management, is illustrated in the quote below.

So I have several layers of management slash areas that I report to because I work for a state government and then I work in emergency services under that. So I’d say my immediate superiors directly above me are extremely supportive. My rosters are extremely unsupportive. The middle management is unsupportive and then the highest management is very supportive.

Due to demonstrated hostility, informal sanctions, and discrimination commonly faced by reservists in their workplace, many choose not to inform their managers or workmates that they are a member of the ADF Reserves. This concealment occurs even when reserve service technically creates no clashes with current civilian work commitments. As highlighted in the first quote below, for this reason some members prefer to use annual leave rather than apply for Defence leave to undertake ADF training and exercises. The second quote illustrates how particular cases, in this instance tensions with employers/managers around Defence leave as stemming from involvement in the 2020 Black Summer bushfire mandatory call out, see them keep quiet about their reserves service. The third quote illustrates that some members will conceal their involvement in reserve training and exercises (such as those activities undertaken at weekends) in order to avoid the imputation that it diminishes their productivity and ‘readiness’ at the start of the civilian working week.

I’ve done Defence work whilst I’m taking annual leave … I’ve elected not to use it (Defence leave) because I do not want to make it a negotiation case.

And that’s from basically the bushfires onwards is when I kept all of my Defence activities a bit more private and didn’t tell them what I was doing on the weekends, don’t tell them about Tuesday nights and just keep that to myself.

a lot of my Defence activities I just keep private, confidential to myself … in their eyes if I go away on the weekend, get 6 hours of sleep that’s going to mean I’m less productive on the job come Monday. So if I tell them that, hey I had a great weekend, learnt a lot of new skills, want to bring these back to the work environment they’ll, they won’t hear that first half of the conversation, they’ll hear, you only had 6 hours of sleep and you’re not going to bring the best to the job today.

We suggest that hiding military service in this way, and not using Defence leave where the right exists, is likely to result in reservists having long term difficulties in sustaining civilian and military careers simultaneously. These problems relate both to workload management and the member’s opportunity to maintain a cultural identity linked to their military service. This situation will likely contribute to attrition rates in the Australian Army Reserves. This finding also has consequences for policy development around how reservists can play a type of ambassadorial role for the ADF within civilian workplaces. As advocates for the ADF, reservists can help build better relations and understanding between the civilian and military spheres, including in relation to recruitment.[xxxiii]

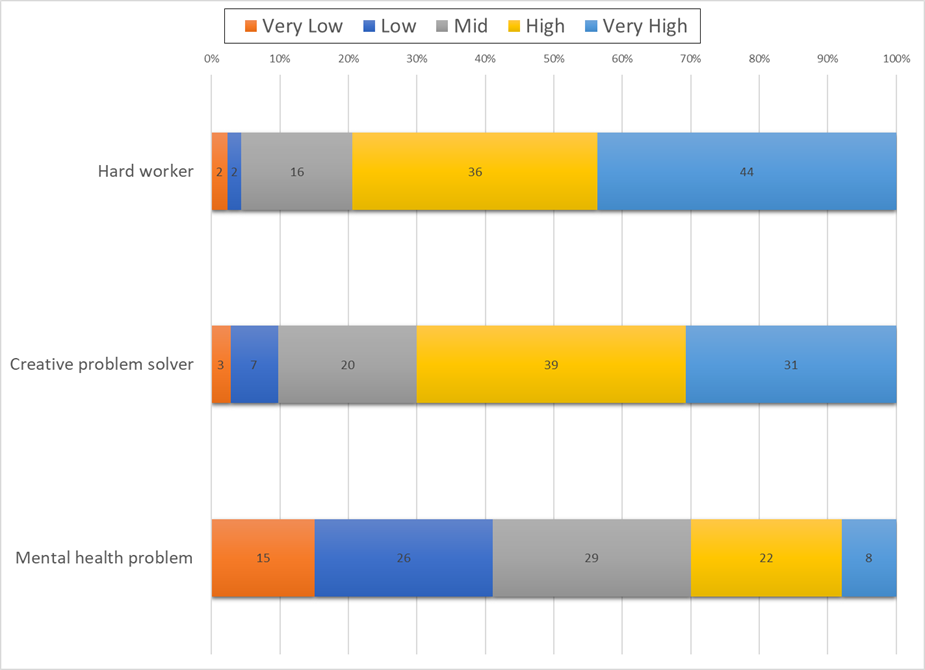

Finding 2: Lack of appreciation for transferability of skills

Our survey reveals that employers/managers have a generally positive view of reservists as employees. For example, the overwhelming majority indicated that they would expect the hypothetical reservist John to be a ‘hard worker’ (80% of respondents thought this very likely or likely) and only slightly fewer (70%) considered him likely to be a creative problem solver able to ‘think outside of the box’ (Figure 4). Notably, there was no evidence of any significant statistical difference in views between the two hypothetical versions of ‘John’ presented in our vignettes (i.e. one trade qualified versus another with a university degree). This finding suggests that reservists are not treated differently by comparable organisations based on their qualification level.[xxxiv] Figure 4 does indicate, however, that stigma may be associated with military personnel in terms of mental health considerations, with 41% of respondents indicating they would not be surprised to learn that John receives regular treatment for a mental health problem. Notably, this perception did not seem to diminish the generally positive managerial view of reservists as diligent and creative workers.

However, such positive perceptions of reservists as civilian workers do not ease the tensions in the workplace that arise around Defence leave. As noted by one reservist in our focus groups who works in a HR role for a large organisation:

I think everyone loves hiring Reservists because it looks great as an applicant … they present really well, they’re really confident, they learn really well … but then there’s that, oh fuck …now we’ve got to let them go, we’ve got all this extra leave we’ve got to approve.

Aside from the workplace management challenges that result from reservists requesting Defence leave, some employers/managers (and even reservists themselves) have doubts that the skills attained through military service easily translate to – and confer advantages in – the civilian workplace. The quote below illustrates the dichotomy between the appeal of employing reservists for their perceived personal characteristics, and a level of residual scepticism that military training and part-time military service offer real benefits to employers and organisations.

Management loves to put the word forward, super supportive, love the Reserves, Defence Force, yeah let’s go. But the second it comes to jumping on a course, they question everything. They question the importance of the Defence Force and that course. They question whether I really need to be going to that course.

The degree to which doubts exists around the utility of military skills was quantified in our survey results. Specifically, nearly 4 in 10 employers/managers (39%) indicated that they regard John’s military training and experience as having a low or very low relevance for his ability to be a good employee in their organisation (Figure 5).

In terms of the reservists themselves, many felt that their military roles do indeed provide them with personal characteristics and values that make them better civilian employees. There was nevertheless a general acknowledgment that it can be difficult to ‘translate’ military skills to their civilian jobs. This is not only because civilian employment is commonly in fields vastly removed from the military. It is also a consequence of the organisational and hierarchical differences between the two domains, with military organisations typically having a division of labour that is shaped by the necessity of having broad skills, whereas many civilian roles are more specialised. As illustrated in the quote below, this mismatch often creates a perception among reservists that there is a lack of mechanisms within civilian workplaces to recognise and utilise for their broad military-derived skillsets and experience.

… from my experience in the ‘civiland’, particularly with State Government, roles are very specific. So a HR manager of somebody with a Bachelor or a Diploma in HR. A manager is somebody with a training in leadership of management. A workplace health and safety advisor is somebody with a workplace health and safety certificate, diploma, bachelor’s, whatever. In Defence, our roles are generalised because we have the mentality that you’re a soldier first and you have to be capable of doing everything. So in my role as a platoon sergeant, I’m partly a HR manager, so managing HR issues between soldiers and passing them on the team. I’m also a workplace health and safety supervisor, I’m also a leader and a manager and a logistician and on top of that, I’m also a clinician… it doesn’t translate well over there (civilian workplaces), because they’re so specific and so specialised.

The difference in prevailing organisational cultures between the ADF and the civilian workforce is a further factor that contributes to reservists’ reluctance to be open with employers and co-workers about their military service. As highlighted in the first quote below, reservists readily acknowledge that the organisational culture of the Army (as it relates to authority, teamwork and communication) does not easily translate to civilian workplaces. As illustrated in the second quote, so marked is the difference between the civilian and military work spheres that communication itself is a challenge when speaking about the military to civilian colleagues.

that’s probably a necessary thing and what’s accepted here, as normal human interaction may not be accepted outside of this uniform, people don’t like it when you call them certain words, right.

There’s still a lot of conjecture about what they actually do in health, in army, because they just don’t know. And the hard part is, you can’t really tell them because it’s different, it’s so different to what they do in Civi Street that unless they’re actually in the system and doing it, you can’t really tell them. So from a perception perspective they don’t know because quite frankly they just don’t know, they don’t do it. And it’s hard to broadcast something when they have no relativity to it.

For reservists, such organisational cultural differences can make it easier to maintain a separation between the two worlds. For example, one reservist noted how they deliberately facilitate compartmentalisation by having a cupboard at home for their army gear that, outside of periods of service, remains out of the way. In other cases, though, reservists feel pressure to conceal their military service due to a perceived incompatibility of military and civilian work identities. For example, as illustrated in the quote below, some reservists would never be seen leaving work in their army uniform, even when it would be highly convenient to get changed at work on the way to parade. This is not due to a perception of anti-military sentiment within the workplace but rather relates to the difficulty of “being comfortable” in having such dual identities.

I refuse to change into my uniform at work because it’s just, it’s seen as unusual in that workplace. Although there are multiple members, none of us get changed at work just because yeah. It would save me over an hour and a half, 2 hours on a Tuesday night to get changed at work but we just don’t do it so-…I don’t know, it’s just, I don’t know it’s a bit of a, more of being comfortable within that shop, not being questioned about it, not asking why you’re doing it or they’ll think that you’re trying to flaunt….

In other ways, the organisational culture of the ADF, and specifically that part which stems from the full-time regular forces, can unnecessarily cause or exacerbate notions that there is an incompatibility between civilian employment and Reserve service. Most prominently, participants in our focus groups consistently emphasised the frequency with which they are given short notice of their confirmation on a training course or sometimes of a course’s cancellation after work leave has already been arranged. Consider the below quotes as evidence of the monumental difficulty and strain these situations cause in the relationship between Reservists and their employers/managers.

We’re constantly in a situation as Reservists, we don’t know if we’re on a course until the course starts. We try to give your employers as much notice as possible and we tell them that it’s tentative and they’re still quite surprised when either we get pulled off the course or we get confirmed at the last moment so yeah.

… panelling for courses can be a week prior to the course date starting so you actually don’t really know if you’re actually going to be away or not and then it's a very awkward conversation where you’ve asked for gracious time off to go and do army reserve training and then you’ve got to walk back with your tail between your legs because you haven’t been panelled on a course that you thought you were going to get on. So I think the army can probably do better in that respect for Reserves.

my employer asked for the training schedule for the entire year. And I gave it to them and I said “Here’s the training schedule but it’s almost worthless because we chop and change the dates we train, courses will pop up, they’ll disappear and I don’t get confirmed on these courses until some times the day of the course”. So yes I can give you a training schedule and they’re expecting that to be a road map, they’re okay so now we can process your leave correctly and I’m like it doesn’t work like that. It's got to be an understanding of the tentative nature of Reserves and they don’t have that at all, at least mine doesn’t.

As one reservist noted, this tension is the outcomes of actions of ‘the army side, not the employer side’. Most of these courses have both permanent Army and reserve participants, with their scheduling and mode of delivery not designed with the needs of reservists or their employers/managers in mind.

Finding 3: The significance of comprehending the military’s intrinsic importance

The degree to which employers/managers perceive that the military is intrinsically important is a critical factor in determining the level of support they provide to reservists’ part-time military service. It is also a critical motivator that shapes whether reservists continue ADF service when faced with disincentives from their civilian workplaces. Thus far in this paper, we have argued that capacity factors, rather than ideology, is the primary factor driving hostility, informal sanctions and discrimination against reservists. However, generalised support for the military, as measured by our survey question ‘Do you think that Australian governments should spend more or spend less on the military?’, emerges in the data as a strong determinant of whether employers/managers think their organisations are willing and able to support reservists in taking leave for military commitments.

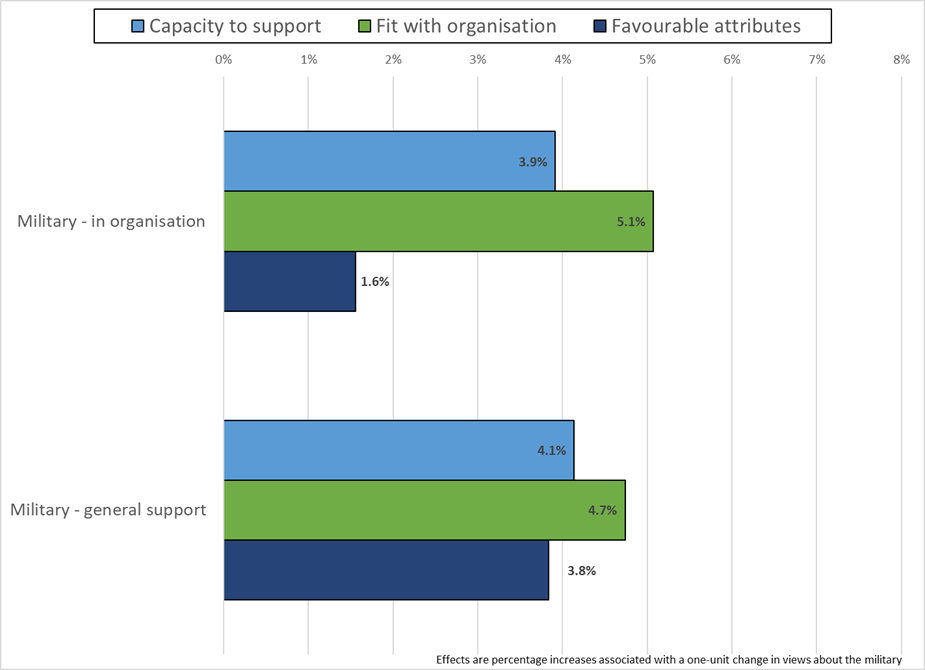

The importance of support for the military for influencing levels of support for reservists in the workplace is depicted both in Figure 3 and Figure 6. In the latter, we see that general support for the military easily surpasses general opposition, by a factor of nearly 3 to 1. Over half (55%) of our employer/manager survey respondents are in favour of increased military spending by government while only 20 per cent favour a reduction. Figure 3 illustrates the estimated relevance of the different levels of military support (net of other differences) on the perceived capacity of organisations to support Defence leave. Our results indicate that (all else being equal), each increment of favourability toward the military translates to a 4.1 per cent increase in the mean perceived organisational capacity to support reservists. Put simply, we estimate that this capacity would be 33 per cent higher for an organisation in which the employer/manager believes ‘much more’ should be spent on the military, compared to an (otherwise similar) organisation in which their preference is to spend ‘much less’.

The positive association between general support for the military and support for reservists in civilian workplaces stands out prominently in our results. In contrast, once other factors are controlled statistically in our models, the demographic attributes of our survey respondents (including age, education level, gender, and cultural identity) have little relevance to their support for reservists in civilian workplaces. Equally, the level of education held by the reservist is irrelevant, as is the respondent’s belief as to the political ideology prevalent among the workers in their organisation. Instead, general perceptions of the ADF are found to have the most impact on reservists’ experiences in the civilian workplace and the extent to which their requests for Defence leave are supported.

The connection between broader attitudes towards the military and how this plays out ‘at the coalface’ is illustrated by the following quote from a reservist in one of our focus groups:

I’d say the greatest things that my employer could do to support my Reserve life would be have a better understanding of the Defence Reserve Protection Act and why it exists. It’s sort of the larger, whole picture of Australia thing instead of oh you just go work for army. It’s a you’re contributing to the national interests, so as a state employer you need to contribute to national interests regardless of your own interests. They have no understanding of that at this stage...

Our survey Question 5 garnered little evidence that a ‘support the troops’ sentiment results in preferential treatment of reservists over other co-workers and job applicants, even among those employers who declare their support for the military. The median employer/manager indicated that they would be unlikely to give any preferential treatment to the hypothetical reservist, John, if he were being considered against an equally qualified candidate for an internal vacancy (see Figure 5). Interestingly, we also found that (all else being equal) large organisations (those with 200 or more employees) are systematically less likely to provide preferential treatment to reservists. We presume that this result is because managers in such organisations are bound by obligations to adhere to policies requiring merit-based recruitment processes. The notion that reservists might derive some civilian career advantages from their military service was discounted or even ridiculed by one reservist in our focus groups. He responded to this suggestion by stating spontaneously: ‘I’m sorry…. That sounds like a joke to me honestly, sorry. That sounds ridiculous.’

The support that reservists receive in their workplaces is not only related to attitudes towards the military generally, but also specifically to the role of the Australian Army Reserves. In contrast to full-time military service, our respondents observed that reserve service was widely misunderstood and underappreciated by employers/managers. Our focus group evidence demonstrates that some reservists feel obliged to actively justify their reserve service by advocating for the importance of the military in society generally.

…not every employer or fellow employee is positive to the defence force… a lot of people are quite negative about I guess the role the army plays in society (resulting in)… tough conversations with managers and other employees about why we are actually in defence in the first place.

There is a common perception that reservists are not authentic military members (a view perpetuated by the common reference to them within Australia as ‘Chocos’ – that is, chocolate soldiers that are likely to melt when exposed to heat). There is also a perception that reserve service is motivated by either mere financial concerns or a wish to ‘play soldier.’ Both views undermine the legitimacy of reserve service. Consider the quotes below, which speak to the material effects that such perceptions have on the experiences and levels of support experienced by reservists in their civilian work roles.

Yeah I remember my old general manager always used to say [he is / I am] off playing – playing army this weekend. So take – taking the piss, you know? So accepting of it, and letting me go, but at the same time, probably showing that he’s not happy about it.

a lack of understanding [they] think it’s either a holiday or a hobby or just something fun to go do on your days off or a cash grab… I have been bullied at my workplace for being a Reservist, like when I’ve told people I’ve got to go away for 2 weeks they’ve been oh playing the system, I would too if I could do the army job, I’d got get my tax free dollars as well. And then I try to explain to them look if something big happens in the Pacific tomorrow I might actually have to go to frontline and then the reply back to that has been no, we’d never send Reservists to frontline.

Contrary to such beliefs, our results overwhelmingly show that reservists are motivated to continue their part-time military careers by intrinsic factors. In most cases, it is a volunteer ethic of service to the community and a sense of patriotism that our focus group participants reported as their main motivations for continuing to serve in the Army. This sentiment exists despite the significant tensions their status as reservists can cause in the workplace, and the fact that there are few, if any, direct civilian career advantages. To appreciate this motivation, consider the quote below:

So I’d say my main motivation for continuing with the Reserve space even though it results in sometimes a loss of pay compared to if I just went and did overtime at my civilian work, main motivation is I feel like I’m contributing to Australia’s national interests, something that I believe in. I kind of believe that every day I’m here helping train someone else is a day that we’ve got 1 more person to help during the next big conflict or next big emergency. So that’s my main motivation. It's not the money, it’s not necessarily the lifestyle, it’s just contributing to something larger than myself.

This is not to suggest that financial renumeration is not also a significant issue for reservists. Our results suggest that military pay has an important symbolic value to reservists in compensating them for the detriment caused by their military service to the prospect of advancement in their civilian career. It also helps them to justify and quantify to others (such as workmates and family) the benefits of reserve service in an age where they perceive that their intrinsic motivations are largely unfashionable.

Endnotes

[xxx] We do this by estimating regression equations in which the influences of other important variables, including industry differences, are statistically controlled for, so that we are left with the effects uniquely attributable to organisational size.

[xxxi] Muhammad Masood Azeem and Bernice Kotey. ‘Innovation in SMEs: The role of flexible work arrangements and market competition’. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 34(1), 2023: 92-127.

[xxxii]OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) ‘Australia’ chapter in Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2024: An OECD Scoreboard. OECD iLibrary, 2024. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1787/40171991-en (Accessed 2 April 2024).

[xxxiii]Eyal Ben Ari, Edna Lomsky-Feder, and Nir Gazit ‘Reserve Soldiers as Transmigrants—Two Decades On: A Research Note’. Armed Forces & Society, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X231223541.

[xxxiv] We also tested, but found no evidence to support, the possibility of differential treatment when the qualification of the survey respondent matches that of the hypothetical Reservist, John. For instance, university-educated managers might conceivably have favoured Reservists who also hold such a qualification – but we found no evidence of any such bias or preference in our results, after controlling for other measured differences in organisational and respondent attributes.

Recommendation 1: Increase awareness of legislative protection amongst SMEs and middle managers

In response to Finding 1, we recommend the need to further encourage voluntary adherence to the Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act by raising awareness and understanding amongst SMEs and middle managers regarding the legislative protection provided to reservists seeking Defence leave to undertake military training and deployments.

Current compliance strategies and advocacy for ADF Reserves largely focus on attaining commitments from corporate leaders. However, a clear finding of this study is that small businesses provide the least support for reservists and that larger organisations (even those that declare themselves to be supportive reserve employers) also engage in discriminatory practices. This is because it is middle managers (not corporate leaders) who are most often responsible for making decisions and interacting with reservists concerning their leave entitlements.

While large organisations may currently employ (and have traditionally employed) most Australian Army reservists, mobilisation of the kind outlined in the DSR – and any strategy that envisages greater utilisation of reserves – will require that personnel are drawn more broadly from across the workforce. This includes industries that are dominated by SMEs. Accordingly, existing compliance and enforcement strategies need to be re-evaluated. Any new approach should follow contemporary best industrial relations practice in protecting worker’s rights. This includes strategizing around how technology can be utilised to widely disseminate information about what the legislation means in practice and developing regulatory mechanisms for the monitoring of offences, such as workplace audits.

Recommendation 2: Human Resource support for aligning military and civilian careers

Industry-reserves relations would significantly benefit from reservists being provided with greater HR support from Defence. This recommendation specifically relates to providing increased certainty and notice of scheduled training courses and facilitating communication with employers/managers around how particular training skills are relevant to civilian workplaces.

Much of the compliance strategy around the Defence Reserve Service (Protection) Act assumes that employers will highly value military work skills. However, our survey of employers/managers indicate that this is not the case and that, for a variety of reasons, reservists seek to conceal their military service. While current employer engagement strategies used by Defence seek to promote the wider relevance of military service to the public, they do so in a generalised way. The approach is largely ineffectual in addressing the main conflict point that arises between civilian employers/managers and reservists: the need for (and relevance of) Defence leave.

A more effective approach would be for materials to be developed that articulate to different industries and occupations the transferability of skills attained in specific military courses, and where possible having these courses recognised through national accreditation. Such materials would also be relevant for fulltime regular members of the ADF in addressing military to civilian transition challenges.

Defence’s HR support to reservists should involve medium term career plans that cover both military and civilian career ambitions, with training schedules set through an ongoing dialogue between reservists and their civilian employers, so that the skills attained can be seen to benefit both the civilian workplace and the ADF.

Recommendation 3: Enhance public understanding of the ADF

The contemporary security environment is characterised by increased geo-political competition. At the same time, among Western nations there is an unprecedented ‘gap’ in levels of understanding between civilian society and the military. Strategies to address issues such as recruitment and retention in the reserves need to be underpinned by broader efforts to build sensibilities towards national defence efforts. While the 2024 National Defence Strategy emphasises the importance of ‘National Defence’ and how it is needs to be underpinned by a coordinated, whole-of-government and whole-of-nation approach, it does not address how cultural understanding by the Australian public and industry towards the ADF can be enhanced. The current model of military professionalism is one that seeks to define military service as a civilian-like career,[xxxv] but it does this to avoid the traditional links of honour and patriotism with military service, and in doing so seeking to professionalised model operate in relative isolation from the sacred yet highly contested civil codes that underpin society.[xxxvi] Yet, as our data indicates, it is likely that greater emphasis on military service as a patriotic service will be required if industry is to support Australia’s whole-of-nation ‘National Defence’ strategy when it comes with some disruption to operations.

As reservists are at the junction of civilian and military worlds, it is important that their sense of duty and patriotism as motivators for service is adequately recognised. However, our study indicates that many reservists themselves feel that that these motivations are not adequately recognised, not only by their employers/managers but also by the ADF, as the difficulties and sacrifices involved in balancing civilian and military careers are not adequately appreciated.[xxxvii]

Endnotes

[xxxv]Samuel English, Phillip Hoglin, and Alice Paton. ‘Is the ADF an Institution or Organisation?’ The Forge 14 May, 2024. Accessed at https://theforge.defence.gov.au/article/adf-institution-or-organisation

[xxxvi] West and Carter 2024

[xxxvii] For additional insight into the desire of reservists to have their sacrifices recognised see Jodie Lording ‘Paid Volunteers: Experiencing Reserve Service and Resignation’. Australian Army Journal. 12(1), 2015: 90-110.