- Home

- Library

- Occasional Papers

- Benchmarking Bottom Up Defence Innovation in the Australian Defence Force

Benchmarking Bottom Up Defence Innovation in the Australian Defence Force

An International Comparative Analysis

This paper reports the findings from a study of bottom-up innovation in defence organisations. It presents a comparative study of bottom-up innovation activities at the Australian Defence Force (ADF), New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF), United States Armed Forces (US military), and British Armed Forces (BAF). The NZDF, US military and BAF are benchmarked against the ADF with the purpose to identify best practices in bottom-up innovation and to identify gaps in best practice in the ADF.

To fulfil this purpose, the study traces the relationships between levels of authority, funding opportunities, innovation practices, open innovation, and measurement. It further describes how bottom-up innovation builds upon an innovation system grounded in people, structures and culture. The benchmarks thus derived are intended to help the ADF to develop a sustainable innovation capability that adds to its ability to deter potential adversaries.

The study is primarily grounded in the qualitative analysis of 29 interviews with personnel working on bottom-up innovation at the ADF, NZDF, US military and BAF at various levels of authority across various branches. Additionally, the researchers created a database of over 500 documents on bottom-up innovation in the defence organisations of 18 other countries. Of these documents, 397 came from the four militaries under comparison. The remaining 100-plus documents were used in a later stage of the analysis to corroborate the findings. We identified nine benchmarks. The benchmarks inform the governance (three), innovation processes (three) and organisation (three) of bottom-up innovation in the defence sector.

The three benchmarks for governance are senior leadership support, strategic alignment, and funding. The ADF performs strongly against these benchmarks, but there are gaps in senior leadership involvement and longer term strategic alignment, and an overreliance on ad hoc and competitive funding. It is also noteworthy that the coordination of joint bottom-up innovation initiatives lies with the branches, while elsewhere it is coordinated at a ministerial level. This situation might explain difficulties in sustaining joint activities and cross-branch learning.

The three benchmarks for innovation processes are methods, open innovation, and measuring impact. The ADF is bringing many methods to bear. An oversight, however, is the relative absence of stage gate approaches. ‘Stage gate’ is a project management term that refers to a methodology that improves project outcomes and prevents risk by adding gates, or areas for review, throughout your project plan. While it might suit the ADF’s operational and technological demands for advancing innovation, the downside is that opportunities are missed for design thinking, agile, and lean startup. It leads to difficulties in transitioning solutions into continued application. The ADF is strong in open innovation, but there are still opportunities for it to learn from the US military and the BAF, which have both doubled down on open innovation and have larger national innovation systems to draw on. Measurements of innovation performance are in place at the ADF, but need reviewing as regards the specific demands and processes of bottom-up innovation. The present measures are too static.

The three benchmarks for organisation are people, structure, and culture. The ADF has invested in the people benchmark but could improve embedding bottom-up innovation in its organisational structures. Without this, bottom-up innovation could fade. Culture remains a benchmark under development, not only in the ADF but more broadly in each of the studied militaries.

Articles in journals, newspapers, and websites from around the world describe bottom-up innovation at defence organisations. Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, the UK and the USA are represented. Bottom-up innovation is defined as involving staff members across organisations in the continuous improvement and adaptation of capabilities. The documents describe activities that encourage and enable staff from all ranks to innovate and improve force posture and design from bottom up. Examples of bottom-up innovation initiatives are makerspaces, hackathons, idea-pitching events, incubators, and agile sprints. With the introduction of these initiatives come new roles, such as innovation coach, innovation ambassador and innovation mentor. There exists, so far, limited research on the bottom-up innovation within militaries. Best practices, benchmarks and suitable management approaches to help sustain these efforts remain to be identified.

This report addresses a gap in research by presenting the results of a study of bottom-up innovation within defence organisations. The purpose of the study was to identify and compare bottom-up innovation in the militaries of selected countries and to benchmark them against the ADF. Identifying areas of excellence, gaps and opportunities shows a trajectory towards the achievement of greater capability across all services and arms. The report informs ADF personnel working in bottom-up innovation on how to improve their efforts, provides senior officers with information on how to assess the performance of bottom-up innovation, and promises to strengthen the development of a stronger sovereign capability.

The four countries selected for this study are Australia, the United States of America, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. The modes of data collection were interviews and the accumulation of publicly available information from online and offline sources. An ethics approval from the Defence People Research—Low Risk Ethics Panel covered the data collection and analysis. The analysis process involved searching for strengths and weaknesses in bottom-up innovation initiatives within the defence sectors of the four countries studied.

The bottom-up innovation initiatives identified within defence organisations, and the language used to describe them, had parallels within private sector companies and non-profit and government organisations. This fact indicates that defence bottom-up innovation is at least in part inspired by the wider discourse and non-military practices. Uniquely however, the defence context sets specific boundaries for innovation work in terms of safety, security, strategic alignment, and transfer of solutions into the system of existing capabilities.

On the following pages we first provide details on our methods. We describe the type of data collected, identify the kind of benchmarking analysis undertaken, and explain how benchmarking can provide actionable information. The methods are followed by a brief overview of the four studied militaries. This overview is meant to put the four militaries into perspective, noticing that there are large differences between them, although they are allies in the Five Eyes network. Then we turn to the topic of benchmarks. The benchmarks are closely related within three identified groups: governance, innovation process and organisation. We conclude the description of each benchmark with notes on gaps and opportunities. A brief discussion of future work on benchmarking in bottom-up innovation concludes this report.

We applied a constructivist research lens to benchmark the ADF against the NZDF, the US military and the BAF (Charmaz, 2006). The goal was to better understand bottom-up innovation initiatives and measures of success based on empirical data and the current literature. Constructivism is an interpretive method that is a suitable lens through which to study ongoing developments, because it enables systems to be seen through the written and spoken language of immediate participants and stakeholders. This means looking at how practical understandings emerge around bottom-up innovation and identifying what works and what doesn’t work, how innovation might become sustainable, and what possible objections and challenges persist.

Benchmarking Approach

Benchmarking allows organisations to adapt. It involves a process of examining key metrics and practices and comparing them to understand how and where the organisation needs to change to improve performance. Benchmarking includes several stages: planning, data collection, analysis, action, and review. Of these stages, this report covers the first three. It also includes a list of recommendations for action. It is for the audience for this report to decide which actions to take and to review their implementation.

Of the various forms of benchmarking, this report presents an external approach to practice. Practice benchmarking involves gathering and comparing qualitative information about how an activity is conducted through people, processes and technology. It results in insights into where and how performance gaps occur, and what best practices the organisation is already applying. Benchmarking is external, because it compares the practices of one organisation to several others, all of which need to agree to participate in the exercise. The authors of this report act as a third party to facilitate data collection and analysis, thus avoiding conflicts of interest.

The objective of the benchmarking study is to gain insights into the current state of bottom-up innovation in the four selected militaries, which allows us to set baselines and determine goals for improvement. Practice benchmarking is recommended where an activity is relatively new to all comparable organisations and key performance indicators are not yet identified. A quantitative benchmarking study might follow up on the results, operationalising the discovered concepts and developing valid and reliable measurement instruments.

Data Collection

To capture bottom-up innovation, an initial list of key concepts was compiled through an exploratory search in international defence journals, newspapers and websites. Based on the publicly available information, we expanded our search to non-classified strategic documents, reports, conference presentations and similar. Our search produced 544 documents from 18 countries. The collected documents indicate the existence of diverse bottom-up innovation initiatives in militaries around the world.

a) 397 publicly available and non-classified documents (Australia 127; New Zealand 13; United States 211; United Kingdom 46) and (b) 29 semi-structured interviews with key personnel involved in military innovation in the selected countries (Australia 16; New Zealand 4; United States 5; United Kingdom 4).

The interviews were each about one hour long and aimed to generate insights into existing operations and activities in bottom-up innovation. The target participants were past and present members of defence forces and associated private organisations managing bottom-up innovation. In terms of demographics, all participants were over 18 years of age. We concentrated on experienced (10-plus years of service) people who work or worked with defence innovation in a managerial position. We assessed this group as being the most knowledgeable about the organisational aspects of how to create and maintain bottom-up innovation. An anonymised list of participants is attached to this report (Attachment A). It provides a notion of the kinds of organisations, titles and entities of interest.

Within Australia, Army participants were from Australian Special Operations Command’s Innovation and Experimental Groups (SOCOM IXG), the 8th and 9th Brigade of the Royal Australian Regiment (8/9 RAR IXG), Army’s Makerspace Pilot Program, and the Robotic and Autonomous Systems Implementation & Coordination Office (RICO) within Army’s Future Land Warfare Branch. Participants from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) were from Jericho Disruptive Innovation and Edgy Air Force. We also interviewed members of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Centre for Innovation within the Warfare Innovation Navy Branch. Further, we worked closely with the Australian Army Research Centre which supported and oversaw the sampling approach.

For the NZDF, the participants were members of the Defence Excellence—Innovation organisation and Defence Industry Engagement. We also interviewed two former NZDF officers who were recognised innovators in humanitarian assistance, logistics, army and air force.

For the United Kingdom, the participants came from the British Field Army, Future Capability Group, Army Innovation Hub, and Army Rapid Innovation and Experimentation Laboratory (ARIEL), which works closely with Defence BattleLab. We also included participants from Defence Equipment and Support, a Ministry of Defence collaboration with the UK military.

For the United States, participants were from Naval X, Air Force Werx (AFWERX), Special Operations Force Werx (SOFWERX), and Kessel Run. Werx is a slang word for ‘works’, used by the military to indicate informality relative to standard operations. One participant was a former senior manager in charge of acquisition and technology development with the US military.

To avoid interviewing too widely and losing focus, Australian military participants were drawn from within target organisations and focal activities that we assessed to be most likely to practise bottom-up innovation. In this way, the source, number, expertise and age of the potential participants was tailored to achieve the aims of the project—the development of benchmarks for defence innovation.

Data Analysis

We transcribed the interviews and, together with the text from the documents we gathered, uploaded them to the qualitative research software NVivo. The analysis followed three steps.

First, we coded the interviews and documents. This process produced a wide roster of codes indicating managerial, strategic, resourcing, methods, behavioural, structural and cultural issues. Sorting the codes resulted in a rough first identification of possible benchmarks. Going back to the raw data, we corroborated the emerging benchmarks, firming up the boundaries and identifying additional concepts that were descriptive and definitive of the benchmarks. This analytic step provided the emerging benchmarks with depth. We arrived at nine major benchmarks, which we interpreted to belong to three groups of benchmarks as reported in this paper.

The second step of our analysis involved creating benchmark tables (provided in Appendix B), where we compared the ADF, NZDF, US military and BAF. These comparisons provided best practices. Once identified, we then benchmarked the best practices against the ADF to affirm the existing practices or to point out gaps.

Third, we drew on the innovation literature to further define our emerging benchmarks and relate them to one another. This allowed us to link our study to a wider theoretical conversation of innovation in non-military organisations and provided the basis for the recommendations in this paper.

Finally, we turned to the documents on bottom-up innovation in the countries that were not part of the main study to corroborate our findings and to check if we had missed something.

We begin reporting our findings with a brief characterisation of each studied military and the scope of their bottom-up innovation activities. According to Global Firepower’s ranking of size and strength (www.globalfirepower.com), the USA holds the first spot, the United Kingdom the eighth, Australia the 17th and New Zealand the 84th. Size notwithstanding, the ranked militaries have a common ambition to engage with bottom-up innovation. The driver for such innovation is a widely held perception of a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous strategic environment, combined with accelerating technological development, which are both difficult for militaries to deal with using traditional research and development (R&D) and procurement processes.

Table 1: Bottom-up Innovation in Selected Militaries

| Australia | New Zealand | United States | United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army |

SOCOMD IXG, 8/9 RAR IXG, RICO

|

Army Innovation Scheme | Army Futures Command; Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) | Defence BattleLab, Army Innovation; ARIEL |

| Navy | Warfare Innovation Navy (WIN) Centres—East and West |

Naval X

|

DARE (Discovery, Assessment and Rapid Exploitation) innovation team; Navy X | |

| Air Force | Jericho Disruptive Innovation, Edgy Air Force (4) |

ABIR, AFWERX Kessel Run

|

||

| Joint | Information Warfare Division—Joint Capabilities Group | Defence Innovation Centre of Excellence | SOFWERX | Defence BattleLab; Joint Forces Command innovation hub (jHub) |

| Government (Department/Ministry of Defence) |

Defence Innovation Hub

|

Defence Technology Agency | Defence Innovation Unit | Future Capability Group, Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) |

| Public-private | H4D (Hacking for Defense) BMNT | H4D/BMNT; National Security Innovation Network | H4D/BMNT |

Australian Defence Force

The ADF consists of the Australian Army, RAN and RAAF. The Australian Army encourages and supports numerous bottom-up activities aiming at incremental innovation for extending and improving the capabilities of existing and continuing capabilities. Notable initiatives are the creation of makerspaces for ideation and prototyping, and RICO for R&D of autonomous technologies. To support bottom-up innovation, the RAN established Warfare Innovation Navy (WIN) centres in Sydney and Perth. These centres function as leverage points for a host of activities, like innovation training, ideation and prototyping workshops, and industry outreach. While most aircraft are sourced abroad, RAAF has created the Jericho Disruptive Innovation centre to explore technologies that support and complement its activities. Jericho seeks to innovate with the help of RAAF personnel and technology companies in order to create new warfare capabilities. The ADF also has several joint operations initiatives in bottom-up innovation. The aim of these joint activities is to avoid ‘reinventing the wheel’ across the three services, and to learn from each other’s innovation successes and failures.

New Zealand Defence Force

the New Zealand Army, Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN), and Royal New Zealand Air Force. With insufficient resources to attain heavy capabilities (it operates no main battle tanks, for example), the NZDF has oriented itself towards bottom-up innovation to extend and improve the use of existing capabilities and to develop technology-driven solutions to complement these. The New Zealand Army has turned foremost to its personnel for ideas on how to improve and develop existing capabilities and to experiment with new solutions. Annual idea challenges and awards play a growing role, expected to feed into the development of a widespread innovation culture. Seeking new ideas and solutions, the RNZN hosted a hackathon together with the RAN that attracted service personnel and external inventors from both countries. Overall, we observe a debate among stakeholders about centralised and distributed innovation activities, with the Defence Innovation Centre of Excellence ostensibly coordinating NZDF innovation.

United States Military

The US military consists of six service branches: Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force and Coast Guard. For commensurability to the other defence forces in our sample, we concentrated on the Army, Navy (including Marine Corps) and Air Force, because they are organised under the Department of Defense. Based on the portfolio of tasks of the US Army, there are numerous bottom-up innovation activities going on. Several organisational entities within Army are encouraging and supporting these activities, such as Army Futures Command and Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM). To provide global vigilance, global reach and global power, the US Air Force is at the forefront of innovation and capability development. Small Business Innovation Research, AFWERKS and Kessel Run encourage, host and support initiatives that explore new technologies with external technology startups and that enable air men and women to be innovative bottom up. Departing from the WERKS template, the US Navy’s central coordinating initiative is Naval X, which runs makerspaces and, more broadly, focuses on building tech bridges to industry. In this it diverges somewhat from the other branches. Notable also is SOFWERX, which sits at the joint level and is very active in the bottom-up innovation and outreach activity of the Special Operations Command (SOCOM). SOFWERX is a public-private innovator of technology, bringing together academia, companies and non-traditional partners to work on SOCOM’s most challenging problems.

British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces (BAF) consist of the Royal Navy (RN), the Royal Marines, the British Army and the Royal Air Force (RAF). Building upon its traditions, the British Army has established several initiatives to drive bottom-up innovation. These include the Defence BattleLab, Army Innovation, and ARIEL, each of which aims to bring new technologies and new solutions to bear on operations and capabilities. Within the RN, the DARE innovation team and Navy X accelerator are tasked to drive bottom-up innovation, providing the groundwork for continuous incremental innovation and experimentation with new technologies. Of the three branches, the RAF seems to be the least involved with bottom-up innovation. Most initiatives run through the Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA), which sits within the Ministry of Defence. With this, the BAF has its central coordinating, funding and initiating body at the government level. Its priorities are to integrate information and physical activities across domains, to deliver agile command and control, to operate and deliver effects in contested domains, to equip defence people with skills, knowledge and experience, and to simulate future battlespace complexity.

We identified nine benchmarks, which cover best practice in governance, innovation processes, and organisation of bottom-up innovation. In each benchmark, we describe best practices across all militaries studied, before benchmarking against Australia to identify areas of strengths and gaps. The groupings reflect that bottom-up innovation is a multifaceted phenomenon involving not only the work of innovators on their ideas but also the dependency of innovation on the support of the larger military organisation.

Table 2: The Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Definition |

|---|---|

| Governance | |

| 1: Senior leadership support | Upper echelons driving, supporting and shaping innovation efforts |

| 2: Strategic alignment | Following and fulfilling the strategic direction set |

| 3: Funding | Budgeting for innovation initiatives and projects |

| Innovation process | |

| 4: Methods | Competently creating or deploying appropriate innovation approaches |

| 5: Open innovation | Tech, ideas and solutions sourced from beyond the defence sector |

| 6: Measuring impact | Gauging the success or failure of innovation outcomes |

| Organisation | |

| 7: Leadership and people | Leader behaviours, mentoring and training |

| 8: Structural embeddedness | Units, rules, norms, reporting and relationships |

| 9: Cultural change | Innovation as the new normal |

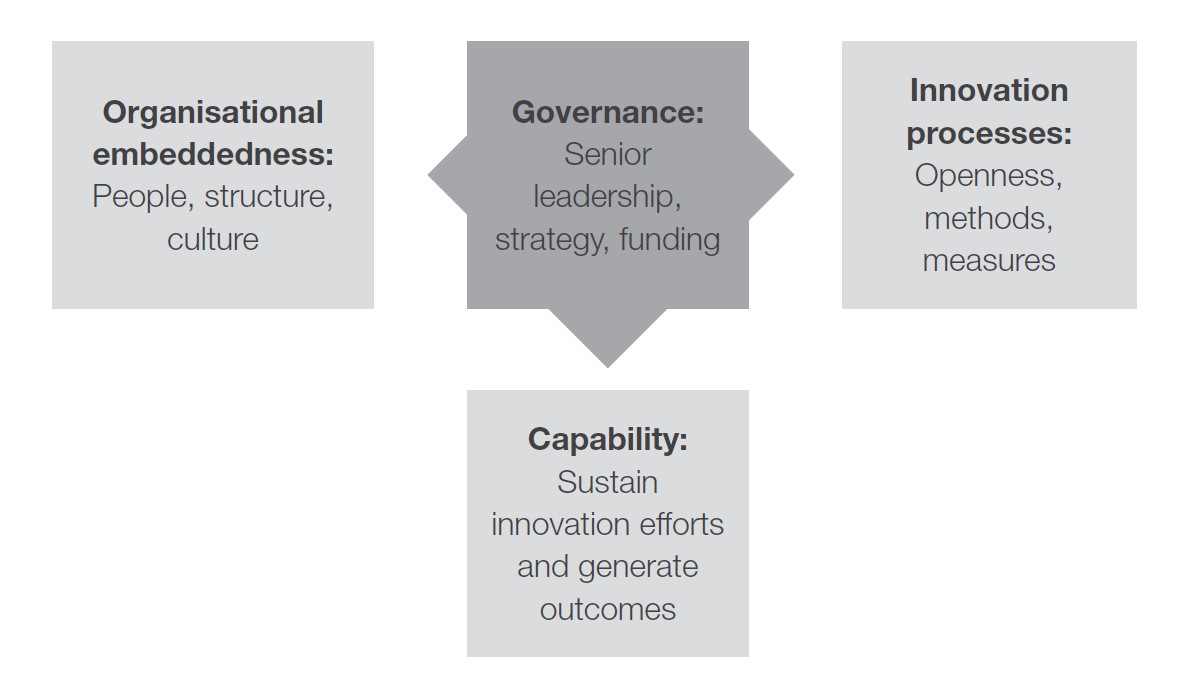

The relationship between the nine benchmarks is not summative but mutually reinforcing. Best practice in one benchmark enables the achievement of better outcomes in other benchmarks as well. For example, excellent senior leadership support for bottom-up innovation usually leads to adoption of a wider variety of innovation methods, which in turn leads to the creation of structures (such as innovation centres or hubs) where these activities are housed and showcased. As this example demonstrates, while the benchmarks in each group are closely linked, they influence the development of the other benchmark groups. Together they create a bottom-up innovation system that is sustainable.

The interdependencies within the bottom-up innovation benchmarks are, however, also what makes balancing and managing the activities difficult. Overly rigid or narrow strategic direction might hamstring the freedom and creativity needed to explore untravelled idea pathways, noticing the overlooked and reassessing the wrongly discarded. Creating innovation centres that house innovation capabilities might relegate innovation to a special task, outside the realm of the ordinary service men and women. Further, centres might get stuck in their own innovation model, increasingly unable to reinvent themselves, which can generate divergence between the priorities of senior leadership and the innovation processes they are tasked to lead. Because of these interdependencies, bottom-up innovation systems are necessarily dynamic and need continuous managerial attention. Success is measured less by the capacity to get it right once and more by the ability to continuously keep it right. This interrelationship of the benchmarks at the service of sustaining innovation efforts and generating outcomes is expressed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sustaining Innovation Efforts and Generating Outcomes

This observation is important when reading the benchmarks reported below. It means that any attempt to improve upon a single benchmark will have positive or negative consequences for other benchmarks.

Governance

Governance benchmarks take a view from the top. Specifically, they present best practices in how the senior leadership enables, fosters and manages bottom-up innovation. Such benchmarks counter a misconception that innovation could ‘bubble up’ from the bottom of defence fuelled by the needs and motivation of individual staff members. Without endorsement, encouragement and resourcing from the top, bottom-up innovation will inevitably be short lived. A key aspect for governance is strategic alignment. Without it, innovation efforts quickly lose their legitimacy. Further, there are several ways to fund bottom-up innovation. While the funding needs of individual projects might be small in comparison to larger procurements, such projects have distinctive needs in terms of human resources, space, equipment, test-and-learn processes, and implementation. We will describe the three benchmarks that together represent governance, identifying for each one how Australia stacks up against the other countries in our sample.

Benchmark 1: Senior Leadership Support

Although it is called bottom-up innovation, it is not sustainable unless it receives senior leadership support. Ad hoc, idiosyncratic attempts at being innovative (where novice service personnel invest their goodwill, time and resources to solve problems within their remit) might occasionally succeed. When bottom-up innovation is to become a regular, sustained and systemic element, however, senior leadership needs to lend its legitimacy and resources. By doing so, leaders motivate and enable junior personnel to apply themselves to bottom-up innovation.

We have loads of high-level support from all over the Department of Navy. I would highlight that we have lots of support from entry level as well, folks that are just coming in 22 years old up to, you know, mid-career. And then we have loads of support again from senior leadership on up, on up. So, the one-star and above, the two-star and above—totally get it. They see the strategic plans that we have ahead of us. They know what’s at stake. They know where we have capability gaps and they are thrilled to try something different. They know that the status quo will not get us there. (Bradley, US military)

Where support remains lip service, and operational concerns dominate the agenda, bottom-up innovation initiatives quickly wither, as our interviewees told us. Motivated innovators become frustrated and move on to other positions or leave the military altogether. To support bottom-up innovation, senior leadership must establish strategic direction, be involved with innovation, secure resourcing, set risk thresholds, and put the right people in charge.

In those environments, people start to leave, and your creatives will start to leave right away because they’ll feel uncomfortable and they’ll stop talking. Or you’ll see a very specific, focused area of technology innovation, and other areas will start to really struggle. Because whatever that individual or that senior leadership team’s focus is, is where everybody will turn their effort, and they’ll just stay within bounds. They’ll be afraid to go outside of it. (Jennifer, US military)

means to single out specific areas of activity for innovation, such as cybersecurity, maintenance, collaboration or mobility. The scope is essential to direct innovators towards what is key and will be supported, and what might be less likely to find approval, no matter the amount of effort invested. It directs attention to those opportunities that fit into the strategic direction.

I just realized I left the copy of my innovation strategy that’s currently drafted that we’ve been working on behind, but the purpose of it really is to—what’s the term?—and I’m struggling here—provide an environment for people to successfully put their ideas forward, to feel safe putting your ideas forward and know that they will be supported to try and deliver those ideas or implement those ideas, or at least, to start the work towards designing the proof of concept, and then with the idea, towards implementing their idea. (Yogi, NZDF)

In our analysis, we noticed that strategic direction is generally set in strategy documents, which are circulated widely and explained at suitable events. The wording of these documents remains at a generalised level, with aim and scope remaining open to interpretation. Senior leadership provides impetus and legitimacy to innovation efforts and offers a wide aim, such as building ‘the force of the future’. Beyond the documents, an interviewee at the BAF explained that detailed strategic direction needs to be given in multiple interactions so that personnel can develop a sense of what is expected and in which way they might invest themselves. It is in these informal interactions that a sense of the importance of bottom-up innovation and its role for the military evolves.

So, there was at work with the leadership team to create an empowered environment to my level. And then there was the reorganisation of our headquarters to move from, the Field Army Headquarters being a traditional hierarchical structure like that, to flattening out our structure and developing agile organisational protocols. So, I don’t know whether you’ve done any work, or you have any understanding of agile reorganisation and agile organisations, but … they have a different approach to a traditional bureaucracy, in terms of their agility, and their ability to respond and the empowering environment they create. (Ivan, BAF)

As our interviewees told us, supporting bottom-up innovation requires a delicate balance by senior officers between maintenance of the status quo and the provision of sufficient space and legitimacy for innovators to usher in novelty. For example, in Australia all service chiefs have been involved in innovation initiatives. In some cases, they give permission for military innovators to operate outside the chain of command. In other cases, such as the Army Innovation Day, they furnish their own expertise to help drive innovation and create the opportunity for personnel to submit ideas for funding support by the Chief of Army. However, developing a sense of the appropriate balance requires knowledge and skill that develops slowly among the ADF’s senior leadership, because this cohort rose through the ranks in times when bottom-up innovation was not a strategic goal.

I think if you were to talk to any really Senior Leader in Defence, you know, they would give you the standard bureaucratic management leadership speak of, ‘You know, we need to innovate to survive.’ And, you know, there’s a bunch of catch words bingo that would be used, but I don’t think any of them. Sorry, not many of them truly know what that means. They know they want it, but they don’t know what it is and honestly. (Lyle, ADF)

Senior leadership sets different risk thresholds for initiatives depending upon their origin. Consider, for example, initiatives involving artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous systems. Large R&D or procurement projects involving such capabilities have high risk thresholds because they require considerable investment in radically new technologies and their adoption

for military use. By contrast, where AI and autonomous systems are part of bottom-up innovation, the risk thresholds are lower due to the experimental nature of the engagement. Bottom-up innovators are attempting to find out what new technologies could do, before large investments are decided upon. This comparison garnered considerable attention in the documents we collected. Military journals and magazines from around the world describe the way senior leaders have approached breakthroughs in tests and adoption of new technologies.

Part of my job from a leadership perspective, is to say, ‘No, but …’. Because saying no is one of the biggest problems now it is a really easy objection to roll out to our people and in so doing, we stop them in their tracks. But if you go, ‘No, but why don’t you think about this?’, So ‘why don’t you go and talk to somebody?’ So, I’m trying … I have … I say, you know, you are not allowed to say, ‘No’, alone. You’ve got to go, ‘No, but’ and give them, ‘You’ve done a great job.’, ‘How about looking at this?’, ‘Why not go and have a look at that?’, ‘Here is a problem I really need solving’, ‘You obviously have the skill set—you can go and do this.’ (Debbie, NZDF)

Senior officers regularly review the risk thresholds across innovation activities. A best practice is to communicate the risk appetite widely, because it informs the focal areas of bottom-up innovation. Comparing the four defence forces in our study, risk thresholds were communicated to innovation centres and individual innovators, and the higher the military budget, and the more technologically sophisticated the defence force, the higher the risk thresholds seemed to be.

And so, we’re pretty agile in terms of what we can get after and how we get after it. But with that kind of top level, I guess management from the Director General level and then the two-star level, Head of Land Capability, we invite Heads to come and see some of those demonstrations. He’s obviously aware on a periodic basis of what we’re doing and what I see … probably a couple of times a week. And then higher, we provide a report to the Strategic Leadership Group, Senior Leadership Group, like everybody else does about what we’re doing. (Robin, ADF)

To guarantee a low risk threshold, it becomes crucial to find, select and nurture specialised innovation personnel. Spotting potential innovators requires attending to personal and professional attributes which may be different to traditional career progression criteria. In the comparison between the defence forces, we found that all four showed care in selecting innovators and putting them in charge of bottom-up initiatives. At the same time, it was not uncommon that roles in innovation centres were filled on a rotational basis, where personnel would step in and out as part of their competence development trajectory. In these cases, there was the danger that the time spent in innovation (between six months and one year) was too short to see projects through or to become deeply familiar with all aspects of bottom-up innovation work.

Best Practice: Provide strategic direction in brief documents outlining aims and scope, and then follow it up by providing further clarity regarding strategic direction on a case-by-case basis. This can be achieved by senior leaders getting personally involved with innovation, including at events, discussions and base visits. By doing so, senior leaders help to set and communicate risk thresholds. Being involved with innovation also makes it easier for senior officers to put the right people in charge with a better understanding of what resourcing is needed.

Gaps: Based on the results of our interviews and analysis of the documents collected, we assess that there is top-level support and involvement in bottom-up innovation within the ADF. Yet maintaining an innovation capability inside an operational unit remains a challenge. We found that ADF senior leaders do provide written strategic direction encouraging innovation, but there is less evidence of their direct and active involvement with initiatives. This left risk thresholds less well defined, and there also seems to be less clarity regarding how to identify, select, challenge and support key innovation staff outside of their volunteering to get involved or being posted to innovation centres in the course of their ordinary career progression.

Benchmark 2: Strategic Alignment

Strategic alignment is defined as a match between what a military can do (based on its strength and weaknesses) and the universe of what it might do (as presented through environmental opportunities and threats). Bottom-up innovation, however, has no clear direction in and of itself. Everything that can be identified as an opportunity might seem worth pursuing. To avoid the risk of misdirected effort, the relevant question is not so much whether an opportunity exists as whether it is an opportunity worth pursuing by the specific branch of the military. The answer to this question is guided through the strategic alignment of efforts.

So basically, our goal is to ensure that we don’t get left behind in what we’re doing. We want to be a Future Ready Defence Force and ensure that our efforts in innovation align with the wider NZDF strategy. (Yogi, NZDF)

Lack of strategic alignment poses many dangers. Without it, innovation becomes a grab bag of techniques. There is a lack of decision criteria for necessary trade-offs. Innovators might imitate the innovation processes and directions of another military. If a military holds the ambition to make innovation a capability, then it is crucial for bottom-up innovation to stay tightly aligned with the overarching strategy. This prevents a situation in which projects are started, succeed in development, but ultimately fail in implementation. It also prevents accusations of money wastage on pet projects, and it prevents the loss of legitimacy among peers and in the eyes of senior officers. Strategic alignment provides a communication platform upon which bottom-up innovation projects can move from development to implementation, then to sustained capability.

Yeah, I think most of them come from my team. So we just explore it and we discuss it, and we build on what it might look and then we consider whether it’s worth pursuing or not. Then we look at how we might pursue it if we didn’t want to pursue it and as I say, a reference is back to something like the RAS Strategy, where it talks about in there making better decisions, using Artificial Intelligence for example to firstly automate, but then inform how we might make decisions. And you know, you could take it to the next step and actually get it to make decisions about we’re all super uncomfortable about that right now, even though it’s doing it for you already. (Robin, ADF)

When military personnel are working at the front line of everyday problem solving, or face difficulties in employing and maintaining capabilities, they can easily become enthused about the prospect of generating solutions which engage their individual expertise and concerns. Such efforts, however, might not align with the overarching strategic direction as envisioned by senior officers.

So, the Air Force produced its strategy last year, which is called ‘AFSTRAT 2020’. And in that we have several lines of effort that we’re looking for people to progress towards, and one of them is upskilling our personnel. So, we don’t mind if somebody fast fails a prototype and it doesn’t work, because there is value in what they might have learned from that journey. And that’s what we see as the upskilling piece. They may not have had a success, but they go, they’re backing the workplace, thinking about something else, and they can draw on those failures or successes that they’ve had working in our … programs for the next big idea. (Nicholas, ADF)

To address the issue of strategic alignment, all four studied militaries locate bottom-up innovation efforts in purpose-created centres and hubs, such as RAN’s Warfare Innovation Navy. Here it falls to the centre director to make sure that ideas picked and supported cluster within the strategic direction. The director becomes a critical link between senior officers and innovators in that she or he needs to communicate the value and alignment of innovation projects upwards, while encouraging, inviting, protecting and supporting individual projects downwards.

The attention to strategic alignment in the short term needs to serve the long-term purpose of bottom-up innovations. In the BAF there is an ambition to go from integration of new solutions and technologies to long-term adaptability as a capability. In the NZDF there is the long-term ambition of setting in motion a self-reinforcing trajectory towards capability enhancement and continuous innovation. The idea is that such a continuous effort will afford and support aligning and realigning to defence policy and strategy changes in response to a changing geopolitical context.

So, it’s really about making sure that all of that type of stuff is in place in line with the senior messaging. In terms of top cover, yes, CGS will absolutely cite innovation as one of his priorities, and it’s in his Army Command Plan as well. It is written in the Land Industrial Strategy that we need to be innovative. So, all of our doctrine, both internal and external facing, will cite innovation as an important part of realizing operational advantage, which then makes it important. (Glen, BAF)

Finally, alignment thought of not only in terms of following a strategic direction but also in terms of identifying, evaluating and aligning to emerging technology for new capabilities. We heard that the ADF framed this approach in terms of ‘technology vectors’ (e.g., a vector might comprise technological developments in autonomous vehicles or generative AI) which would lead to solutions across several potential capabilities. To realise the potential in each technology vector, it is important to bring external and internal stakeholders together in a focused way. Once a technology vector has been established for one military capability, alignment involves mining its potential by identifying, developing and testing whether the technology can be applied to other capabilities.

But out of it came an argument and a debate about additive manufacturing at sea. And now we’re writing and in the third month of an additive manufacturing strategy which will be presented to [Chief of Navy] by the end of the year, financed by Joint Logistics Command. So, this little, tiny project has led to a large Defence capability. And that’s how innovations energise thinking. (Steve, ADF)

Best Practice: Strategic alignment requires a person to bridge the relationship between bottom-up innovators and senior officer strategic decision-makers. Where there are multiple initiatives, hubs or centres, each requires such an innovation director. These ‘bridge personnel’ assure that idea selection, development and implementation fall within the defence force strategy, and he or she communicates the actions taken and the outcomes to senior officers. It has a dual benefit: future top-level strategy making is informed by a realistic view of innovation capabilities and outcomes, and innovation activities benefit from support and uptake from the legitimacy gained through strategic alignment.

Gaps: Benchmarking the NZDF, USAF and BAF against the ADF, we noticed that Australia has suitable bridge personnel in place and strategic alignment is continuously reviewed. However, this study indicates room for improvement in how the activities, and the results achieved, are fed back into the organisational processes that inform future strategy. At the moment, the relationship is unidirectional (from strategic leaders downwards to those engaged in innovation), which is characteristic of an operational organisation but not yet of an innovative organisation.

Benchmark 3: Funding

One of the most critical aspects of innovation is to provide adequate funding. Too much, and innovators can buy their way around difficulties that might otherwise have inspired novel approaches. Too little, and innovators feel like they are asked to make something out of nothing. Apart from the amount, it is also the practice of funding that matters. Discretionary funding provides flexibility, while competitive funding seeks to reward the greatest opportunity, pitching ideas against each other. Both forms of funding have advantages and disadvantages.

. Lengthy documents are written to justify funding proposals, explaining how risks will be avoided or managed to give the project in question the maximum likelihood of success. Preparation of these documents is supported by capability analysts who provide advice and support so that proposals can pass the necessary quality gates before they are tabled at the decision-making level. In much bottom-up innovation work, however, there is too much ambiguity and uncertainty to meet the normal criteria for project progression. A good proportion of the funding provided will have to be written off as a necessary investment into learning what doesn’t work. The advantage of bottom-up innovation is, however, that failure is cheap. Most bottom-up innovation costs only a fraction of other projects that are subject to regular procurement processes. The achievement of innovation, therefore, becomes a game of low cost, ingenuity and speed, rather than meticulous planning and documentation. But how do militaries set up a reliable funding structure for that? Several practices that we found in our study are outlined below.

Now through my funding I have that pre-approved funding to be able to deliver on that Bottom-Up innovation. And that’s where that funding forum funds the ideas. If it’s a fairly simple, straightforward idea, good to work with, we can do it as a Jericho Labs supported idea, or if it’s quite a good idea that fits within a capability priority or has a category sponsor who has a need, then we can provide up to $50,000 to develop out that idea. (Michael, ADF)

When asked, most personnel who seek innovation prefer discretionary funding. It means that a budget is provided to an initiative, hub or centre for a given period, usually one year. The budget comes with an expectation of outcomes being aligned with strategic direction, an agreement on principles to follow, and risk thresholds to observe. The budget can then be applied to as many or as few projects as the innovators see fit. The innovators we talked with favour frugality and tend not to overfund any specific project. An advantage of discretionary funding is that financial support is decided at a level close to competencies, technologies and innovation processes, leading to a more targeted approach. A disadvantage can be that innovators are using the funding towards projects that seem most challenging and interesting to them, which will inevitably lead, over time, to slippage in strategic alignment. Also, funding might go to more radical projects to show innovation prowess.

I’d like to highlight we have a very tiny budget inside of Naval X. We rely on all the rest of the money out there for the Department of Navy to actually do the work. We’re not another funding program to go figure out a contract. And I see that as a benefit, people are not coming to us with their ideas. They’re not coming to us with solutions that they want us to buy, they’re coming to us with ideas that they want advice on, and I can frankly give them unsolicited advice, without giving undue favour. (Bradley, US military)

Ad hoc funding becomes available where bottom-up innovators can prove that their idea has potential. This potential might be outlined in a proposal or a plan, and is usually communicated to senior officers. Ad hoc support provides an opportunity to align funding to risk appetite and strategy, and funding levels can be more accurately weighted against the perceived potential of the innovative idea. For the innovators themselves, however, it presents a lower level of funding certainty and a greater workload to research the exact value their idea might help generate. Importantly, this approach reduces the flexibility available to innovators to respond to knowledge gained during the innovation process by pivoting from the original idea to a more promising one.

Time or whatever, then that unlocks another tier of funding or something like that. I believe a model more agile like that is what we need to move towards if we’re going to remain relevant going into the future, because the danger is we don’t, and then our current capabilities just increasingly become less and less relevant as they’re off the shelf technology just goes through the roof. So the disparity between, private sector then and public sector becomes quite dangerous. (Jono, NZDF)

Competitive funding is gained through idea competitions, ‘shark tanks’ and similar events. To obtain funding, innovators need to pitch their idea against those of other innovators. Innovators might come from inside defence, from smaller companies, or from a mix of both. A judging panel of experts listens to the pitches, reviews the reduced-length innovation proposals, and discusses which idea or prototype has the highest potential. Such competitions might happen at the back end of a hackathon, for example, or there might be a regular schedule for when shark tanks take place. The advantage of winning competitive funding is often not only the financial resource but also the attention that an idea or project gains through winning a competition. It might make it easier for innovators to obtain funding from other sources, such as ad hoc funding. Many of the documents collected presented the winner of idea competitions.

The senior leaders supported this by doing Shark Tank and Spark Tank stuff. So, we had publicity. We had internal learning. The mission itself still exists. And in fact, it continues to grow from what I’ve seen with the new AFWERX regime and stuff like that. So yeah, sustainable because we kept producing enough wins that made it worth the funding because it wasn’t, the Air Force has cancelled more than enough programs over the years if we weren’t giving back positive value and stuff. (Brian, US military)

So far, the funding sources presented are principally concerned with providing money for initiatives that are rooted in defence. With an increase in open innovation (discussed in Benchmark 5) external collaborators are also becoming involved. To position such collaborators to work on their projects with defence, there are government funding opportunities for external collaborators. This funding is meant to put cash-strapped startups in the position to develop and test their services, products or technologies for defence applications, something which they would otherwise have difficulty achieving. Also, the funding provides the respective defence force with a tie to bind the startup to a project and to legally secure follow-through.

I’d like to highlight that the defense and government science funding model is unique in that it funds early-stage research for universities, which provides long-term investment. This is best served by government investment, not by private companies like Apple. The AFWERX is doing interesting things related to the Small Business Innovative Research Program, such as making cyber cool again. However, this is a snapshot in time approach and we should evolve over time to meet the needs of the Department of Navy as we grow. We should be starting to buy new things and depending on old things. The Impressionist approach is not a term of insult, but a way to celebrate the moment in time quickly. We need to be nimble to meet the needs of the Navy going forward. (Bradley, US military)

Finally, an important aspect of funding bottom-up innovation is to secure continuing capability funding for the solutions created and implemented. Once an idea has gone through the innovation process and has demonstrated itself to be an effective, efficient and implementable solution, resourcing needs to pass from the innovation initiative, hub or centre to the normal budget cycles. If this transition fails because senior officers assess that the solutions are unnecessary or still too risky, the solution will likely be abandoned. Therefore, the hand-off of the outcome of bottom-up innovation is a critical phase which goes far beyond the innovation process itself. In the literature examined for this study, innovation is seen as the adoption and normalisation of a new solution, not only its invention.

Best Practice: The militaries in our sample apply a mix of funding models. There are budgets for innovation for one-off projects; there is discretionary funding for innovation initiatives, hubs, and centres; there is competitive funding; and there are funds for working with external collaborators. There is, however, little evidence of continuation funding for new innovations. This is a concerning finding as it indicates a disconnect between innovation and the development of sustainable capability enhancements. Best practice is to provide central actors in the internal innovation ecosystem with discretionary funding, coupled with senior officer oversight and an ongoing demand for the innovation work to be strategically aligned. The same approach applies to ad hoc funding, competitive funding and funding for external collaborators. Best practice sees the funding streams for capability acquisition and maintenance as an extension of the bottom-up innovation system. While several militaries attempt to achieve this outcome through their focus on strategic alignment, we couldn’t find any military that had mastered it.

Gaps: Unlike Australia, the UK has a fixed pool of funds that are made available to support innovative activities across the BAF. There is a team that is dedicated to ‘passing the baton’ to help ideas cross the ‘valley of death’. Also, the US and the UK both have programs where personnel can be posted into an innovation program and receive funding from their home unit or as part of a fellowship. These programs are called ‘tech bridges’, a term which refers to productive networks where stakeholders can share ideas and best practices. The US Navy has seen a proliferation of tech bridges across the country and internationally. Further, there already exists a US-UK collaborative London Tech Bridge. The ADF, which has been less coordinated in the way it applies funding for innovation, could seek to participate in this organisation in order to learn more about the management and funding of cross-sector or cross-military developments.

We selected the term ‘innovation process benchmarks’ because innovation takes various pathways from insight to idea, experimentation, prototyping, testing and implementation. At any point in this process, learning occurs that might prompt the innovator to pivot towards more promising avenues or may pose challenges that need to be overcome. Metaphorically, this is called the innovation journey.

Within the studied militaries, a variety of innovation methods are presently being employed in bottom-up innovation efforts. Most of these methods hail from the private sector, where they have been in effect for the past 20 years or longer. Even the language that is being used to describe bottom-up innovation activities in the military derives from the private sector. This might seem odd because the goals of the two sectors are different, with private organisations innovating for profit and in the interest of their shareholders, and the military sector building and maintaining defence capabilities. The parallels in language and approach, however, indicate the militaries’ willingness to learn from the private sector, to work with it and to experiment with new approaches to innovation that have been developed elsewhere. Ultimately, what matters most for benchmarking is not the genesis of the methods but the kinds of practices in use and their effectiveness in delivering innovative solutions in a military context.

Beyond the methods, there is also a growing concern with open innovation in all studied militaries. Open innovation is an approach where an organisation doesn’t just rely on its own internal knowledge, sources and resources (its own staff or R&D, for example) for innovation. Open innovation affords bottom-up innovation for the purpose of bringing new technologies to bear on defence problems. While open innovation can include a spectrum of innovation efforts, from large-scale collaborative projects to small-scale tests and experimentations, in this report we are concerned most with the latter. For example, the US military includes open innovation in its WERX model, where defence personnel seek out and collaborate with startups and smaller companies to find trends and solutions.

Finally, the studied militaries are demonstrably preoccupied with how to measure innovation. How do we know that an innovation journey fraught with uncertainty and ambiguity is on the right track? Further, what measures are relevant and important to communicate up the chain of command to show that the allocation of funding has achieved results that are aligned with strategic direction? Measuring innovation is a pervasive concern—one to which a satisfactory answer might still be missing. Several interviewees told us that measuring innovation is difficult and agreed that measures of effectiveness are often missing.

Benchmark 4: Methods

Militaries seem intent on testing any method, tool or technique that has been applied in the private sector. Hackathons, pitch events, innovation sprints, and design thinking workshops are proliferating. The trouble is that a military that engages in all possible methods, tools and techniques is most likely acting arbitrarily and in search of what works best. In reality, a gap in the use of available methods doesn’t mean that an innovation practice is missing. It might rather mean that the innovators know why they engage with a particular technique and not another. Relating to the benchmark of strategic direction, the reason for choosing a particular method is more important than trying them all out.

So in terms of innovation processes, a lot of the things you have there have ideas, submissions, organisations, design thinking, hackathons … all those things. I think a fair number of those are used, but it wasn’t in the formal sense that these things have become, you know, these are relatively new phrases. Some of them, you know, solid learning theory research, a [inaudible] environment in order to do work, a small team, very well supported at the highest levels with a bit of funding. That’s really what it took to get that particular innovation off. (Thomas, ADF)

Two observations are key. The first one is that methods are not independent of context. For example, linear innovation processes (such as funnels or stage gates) work in stable environments, where influences and effects are reasonably predictable. In contrast, iterative innovation processes (such as design thinking, agile and lean startup) are made for contexts characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. Instead of keeping innovation in a narrow bandwidth, iterative processes help to solve problems by creating search patterns through which to discover what is in between and at the fringes of existing capabilities. Secondly, another distinction exists regarding experimentation. All innovation processes use experimentation to shed light on what works and what doesn’t work. However, scientific experimentation methods work only when it is possible to isolate the issue under consideration. Scientific experimentation begins with a hypothesis that will be tested to create knowledge and possibly lead to a solution. Accordingly, it finds its place in linear innovation processes. Creative experimentation, in contrast, works without hypothesis and draws more on broad events or activities that allow staff to explore bottom-up issues following their interests. The idea here is that problems and solutions are not centrally defined but are instead part of the search process itself. This is why creative experimentation is a method often used in hackathons, idea contests and other small-scale search processes for new solutions. These events are therefore particularly useful for harnessing iterative innovation.

But to their credit, that has proved certainly when I was in the seat as a success. That design thinking methodology drove itself down through to our Maker Labs and how we conceived ideas, how we tested them, how we iterated them, developed prototypes, iterated again. And that was a journey for some of our senior uniformed leaders and senior public servants that you know, ‘a failure is a success.’ (Lyle, ADF)

The methods benchmark can be organised along two categories: ‘harvesting ideas’ and ‘developing innovation’.

Harvesting Ideas

All four militaries have online idea platforms in place. Some have different platforms to support different military branches. The purpose of idea platforms is to allow service men and women of any rank to submit a proposal for an idea that they have developed, often involving a money- or time-saving way to perform a routine involved in delivering capability. Increased safety is also a possible goal. A committee evaluates the submitted ideas, deciding which ones deserve support. Support might involve two different pathways:

- The person who proposed the idea might receive funding and time to work on the idea.

- The person will be put in touch with staff at the innovation initiative, hub or centre, who will collaborate with him or her on the project. This process is meant to introduce the innovator to the methods of innovation work, which might enable and encourage future engagement with innovation opportunities.

Related to the idea platforms, militaries regularly run idea contests where service men and women, and at times outsiders, present ideas to expert panels, who will decide if the idea warrants funding, resources and support. Many of the idea contests are modelled on the ‘shark tank’ concept that was originally introduced in an American business reality television series. The US military calls such contests ‘spark tanks’. An important characteristic of idea platforms is that they involve innovators participating in an event. Participants receive immediate feedback and a ‘go or no-go’ decision. Further, participation in the contest provides visibility and a certain level of prestige for the participants’ units. It is important to notice the competition format of ideas, suggesting a funnel process where ideas are selected based on explicit criteria. Many ideas will fall by the wayside, especially radical and unfamiliar ideas that are likely to be eliminated in this format.

I’d put up these ideas on social media and allow for that natural, robust discussion to occur across all interested parties. Then find those ideas pitches that were, I guess, the meatiest and we potentially thought had some real interesting outcomes for Army and then at a forum at the back end of the year have a physical event where those idea pitches would like Shark Tank pitch their idea to senior leadership and either get those leaders to invest in that decision, whether that be through a change in process or taking a risk and posting someone to try that job or whether it was money but a lot of the times it wasn’t throwing money at the problem. (Jasmin, ADF)

A third method of harvesting ideas involves hackathons. While hackathons are similar to idea contests in that both involve an event, the difference is that ideas are being developed during the event, rather than being brought to it in a presentable format. Taking from one day to one week, hackathons tend to end with a panel judging the outcome of the hack and awarding funding and support to those ideas that merit further investigation.

So no longer was it intimidating to come in and talk and a lot of people felt comfortable, you know, coming in and having fun and making an impact. So, we would do hackathons where we’d have a specific problem that we were going to solve or that we were interested in people coming up with ideas for. Sometimes those would be a weekend, sometimes those would be a few weekends. We did both physical and digital hackathon solutions, and we also hosted, you know, things like a GitHub online with open source code and different solutions like that. (Jennifer, US military)

Developing Innovation

Makerspaces are inviting service personnel to bring their ideas into a dedicated space that provides playthings, modelling, and experimentation equipment. These spaces are often outfitted with a machine tool workshop to enable the production of minimally viable prototypes. Makerspaces are a standing offer, staffed and managed, which distinguishes them from idea contests or hackathons. And the invitation to work on ideas and to explore their potential and their viability, before presenting them to a committee or panel for further funding and support, distinguishes makerspaces from idea platforms. The methods for the spaces often build on design thinking—i.e., an iterative innovation process—to develop minimally viable solutions.

So, AFWERX had very light prototyping over at the Vegas hub, like they had a shop where you could do a little of that. But through the base innovation offices, you did end up with some different makerspaces both on the 3D printer side of the house with some really interesting like nose cone stuff for the front of aircraft there that they would do different things. (Brian, US military)

We found numerous examples of design thinking within the US military, including training in innovation methods and examples of innovative solutions generated within the Navy, Army and Air Force. While it is not entirely clear what the dominant variant of design thinking was, innovation was undoubtedly applied to problem-solving at the front end of the capability acquisition and maintenance cycle. Design thinking promises a structured approach to creativity that invites innovators to reconsider problems from a user-focused perspective. This human-centric approach makes design thinking an ideal method for bottom-up innovation.

Yeah. I would highlight that that’s a real tenant of Design Thinking [and] Lean Startup methodology, [that is] getting to that test point quickly of, ‘Are we headed down a path that is interesting to a customer or interesting to a user?’, ‘Are we confirming are we living in a space of confirmation bias where we … just kind of think we’re doing the right thing?’ (Bradley, US military)

Our data suggests that ‘agile’ is a popular method for innovation work in militaries. Agile is a project management term that refer to a way of breaking down project elements into smaller, more manageable components called ‘sprints’. Rather than forming a fixed bundle of tools and techniques, agile is driven by principles of collaboration, modularity and iteration. In the interviews, it was evident that many participants used the term ‘agile’ loosely, referring more to an attitude and ambition than to a set of processes. Successful bottom-up innovation was regarded as evidence for agile, whether or not the process of innovation followed agile principles. In the innovation initiative, hubs and centres, however, agile principles were more closely followed. There were clear attempts to enact them in a repeatable fashion to drive bottom-up innovation projects forward.

In different parts of the organisation, agile is being used. Currently, the CIO ironically is in the midst of a transformation program called CISCTP Continuous Transformation Program, and its focus has been very agile-driven like the methodology that’s been used and that is definitely very agile. (Debbie, NZDF)

The third method to work with environmental and technological complexity is known as ‘lean startup’. This approach owes its origins to a methodology that aims at shortening product development cycles and discovering if a proposed business model is viable, involving hypothesis-driven experimentation, iterative product releases, and validated learning. We found it practised in two forms. In the US military, where entrepreneurial behaviour was often referred to, and where reservists and veterans were encouraged to start businesses after their tenure, lean startup was seen as a supportive methodology to allow these service men and women to achieve bottom-up innovation. The other form of lean startup happened outside the defence forces, and it involved collaborating with external founder teams to help them develop solutions that are appropriate for a military context.

We are also teaching Lean Startup, Lean Design Thinking and the tenets of standard waterfall P3M management. Everybody can now say fast-fail, learn by doing, ‘show, not tell’, and zoom out and zoom in. Zoom out as in you have a vision for what you want, ‘Future Commando Force.’ You then zoom in and you iterate. Because as the Navy CTO, I could only see good ideas probably shaping about three months in front of our face because everything is moving so fast. So how on earth could you write a 3 billion pound program for Future Commando Force Modernisation Program over the next 10-15 years? In any actual relevant detail, what you need to do is behave like Space X, have a hopper of cash and then spend X amount a year, iterating and going after it in chunks as you can. And I’ll do a worked example to the minute. (Dan, BAF)

Best Practice: It is difficult to describe one single best practice for the methods benchmark. Makerspaces, idea platforms, hackathons, idea contests, design thinking, agile, and lean startup all indicate tried and tested methods at work. However, the mere presence of all of these across the four studied militaries, with the exception of NZDF, where it is still in development, doesn’t indicate best practice. The reason is that the mix of these methods is directly dependent on application of the governance benchmark. Depending on senior officers, strategic alignment and funding, some of these methods make more sense than others. Further, a more careful consideration of the environment is needed. To assume that the environment is always turbulent is of little help, since there might be at least pockets of stability that support innovation methods that are more linear. The right practice is equal to the right mix under the circumstances with reference to the strategic goals.

Gaps: There is a gap within all arms of the ADF in terms of their demonstrated ability to support ideas that arise from the end-user community at the tactical or operational level. The Australian Army, Navy and Air Force have seen makerspaces on bases and deployable makerspaces in the field and on ships. However, the US Marines are still ahead in the coordinated application of methods. Also, the Defence BattleLab in the UK provides a more cohesive approach. Instead of trying additional processes, it may be more productive for the ADF to concentrate on a strategically aligned signature process. This approach might help foster bottom-up innovation efforts that are ultimately more sustainable.

Benchmark 5: Open Innovation

Militaries recognise that the source of valuable knowledge to help solve defence problems might reside outside of the defence sector. While the military sector has produced innovations that changed the private sector in the past (such as the internet and global positioning system), the flow of innovation seems to be turning around. This might happened due to an accelerated and more distributed development of technological novelties in the private sector. Militaries therefore seek out open innovation activities. These activities enable them to participate in a marketplace of ideas and solutions that benefit the various stakeholders included. Open innovation stretches into national (and sometimes international) innovation systems. For example, the US military has links to Silicon Valley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other centres of excellence and innovation, and is particularly active in this space. The ADF, BAF and NZDF are also involved in open innovation, usually with an eye towards technological advances and how these might improve, complement or amend existing capabilities.

Within IXG, we have established a deliberate annual, quarterly-based framework over the last four years. The last three years have been a venture of discovery into what ‘right’ looks like and when to do particular types of activities. We have weighted our effort in quarter one, where we run an open innovation sprint that invites others from the IXG network, noting that we have helped three other organisations establish a like model within their units. We invite them from across the Army and the Joint community, primarily from the end-user level. We have developed a specific sprint methodology that applies the ‘Think-Make-Connect’ innovation methodology. We run an education package that includes non-traditional education tools that take the best from Lean Six Sigma, Lean Startup, Design Thinking, and Agile. We bookend that with a custom and end-user-oriented framework, which is called the EURECA framework. We provide them with that to enable the teams with specialist experts from industry and DSTG, give them an open challenge and a time pressure of artificial mission constraints around the 72 hour ‘Maker Mission’ window. We allow the teams to provide a prototype demonstrator, a pitch, and pitch that demonstrator to a leadership panel. This year, that included representatives from each of the services at the right level, hosted by one of our One Stars, to provide immediate feedback and, for us, to look at options to take their prototype through. (Benny, ADF)

To engage in open innovation, the first step is ecosystem development. Militaries need to build lasting relationships with external actors. In general, militaries position themselves at the centre of their ecosystem, maintaining independent relationships with numerous external entities—companies, universities, think tanks and so on. Alternatively, careful steps are sometimes taken to generate a more dynamic, multipolar ecosystem. For the ADF this may occur, for example, when solving an identified challenge requires multiple stakeholders to interconnect. In such circumstances, the military is but one actor, contributing to solutions that might benefit its mission, while simultaneously addressing larger societal concerns such as sustainability, environmental preservation, equality or social justice. Of the two types of ecosystem positioning, all four studied militaries profess the former, placing themselves and their mission at the centre and striving to create a diverse ecosystem that benefits their mission and strategy. To begin creating such ecosystems, defence actors invite external parties to conferences, events, meetings, competitions and the like. The US military also maintains offices off base, custom designed for defence personnel to interact with technology startups and other potential external partners.

So the focus there was now how do I scale up the SOFWERX model to work at the service level? So, we created a thing called Naval X, which was really this learning framework that would speed connections and lessons learned. And then we developed as part of that a TechBridge network, as we called it, which I think is now up to 19 different sites, including a site in Japan, one over in England, and probably a couple of others. (Jim, US military)

Once potential ecosystem actors are identified and invited, the militaries proceed to sourcing ideas, technologies and solutions through interactions. The ADF sources from startups, mid-sized companies, private tech platforms, aircraft manufacturers, and universities through a multitude of agreements.

And we also have within Defence Excellence, we have a budget that we’ve used for various activities that are more tri-service across defence sort of activities. It’s quite a small budget but what we’re looking to do going forward is use that for a new program, which was stepping up around Open Innovation and picking projects to push forward with up to 100k, 50 to 100k level projects or maybe even as low as $10k—anything that sort of meets the criteria that we’re going to set. (Yogi, NZDF)

Competitions are a popular and safe way to source ideas and possibilities in open innovation. Defence forces issue a challenge related to a specific problem or interest—for example, unmanned vehicles in rough terrain, technology for smart sensing, quantum computing for defence purposes, or AI for situational awareness. Companies, universities and other external organisations can study the challenge, submit their proposals and—if selected—present them at defence industry events. The advantage of the competition format is that it holds the potential for surprising entries and unusual perspectives which would not have emerged if the military had relied on existing relationships.

So, for public competitions for example, you could go to AFWERXchallenge.com and you can see all our different competitions. And I think you technically have to register [and] leave your email behind. But I haven’t looked in a while since I am retired from the assignment, but it used to be a sign up with an email and then you can look at anything you want. (Brian, US military)