Conceptual Reframing of the Operational Level of War

The traditional conceptual model that divides war into strategic, operational, and tactical levels remains influential within Western military doctrine. While strategic decisions shape political aims, the tactical level encompasses direct battlefield engagements. Between these extremes lies the operational level of command, tasked with linking strategic intent to tactical actions.[1] Recently, this operational level has come under scrutiny, particularly with respect to its relevance and utility for middle powers such as Australia. Critics suggest that it complicates military understanding, unnecessarily separates political and tactical spheres, and that its suitability is limited to large-scale, great-power conflicts.[2],[3],[4] Yet, despite these critiques, this Land Power Forum post will contend that the operational level of war remains vital. Rather than discarding the concept, the Australian Army should reframe it, employing a more dynamic model better suited to contemporary strategic and operational realities.

The debate surrounding the operational level primarily arises from its perceived artificiality and redundancy; which is further exacerbated by its conceptual ambiguity. It has been critiqued for unnecessarily separating strategic and tactical dimensions, often creating a bureaucratic buffer, causing further confusion rather than clarity.[5] It is further argued that this artificial delineation between politics and tactics risks strategic disconnect and undermines coherent policy implementation. Similar criticisms have been made for its role post-9/11, with assertions made that it may exacerbate civil-military divides by enabling vague political directives to be transformed, often ineffectively, into military actions.[6] Furthermore, some suggest that the operational level, introduced into Western doctrine relatively recently during the Cold War era, lacks historical grounding in classical military theory and may no longer be universally relevant.[7] Further, the operational level of war is often conflated with operational art—a related but distinct concept; this conflation can create confusion, both in doctrine and debate.

To maintain analytical precision, this post distinguishes clearly between the two: the operational level relates to ‘where and who’ (a decision-making stratum) while operational art relates to ‘how’ (the methodology applied to design campaigns and synchronise tactical actions in pursuit of strategic effects through major operations). The value of the operational level lies in its ability to host operational art: a headquarters, structure, and staff environment from which campaign design is conducted.[8] For middle powers like Australia, both remain vital, particularly in the context of coalition warfare or autonomous regional operations.

The operational level remains critical precisely because it provides a structured setting for translating broad strategic objectives into coherent tactical outcomes (i.e. operational art), essential in joint or coalition environments. Australia's unique geostrategic challenges require a flexible yet disciplined approach to military operations, emphasising the need to undertake operational art effectively. Australia, often operating within coalitions or alliances, must reconcile its national strategic objectives with the operational dynamics led by partner nations. Having an operational level of command, staffed with personnel focussed on the operational art, ensures tactical interoperability and strategic influence within such contexts.[9]

Moreover, operational art offers essential analytical and organisational advantages. Critically, many of the arguments made against the operational level are in fact arguments against poor operational art. Examples of vague political aims devolved to theatre-level commanders illustrate the dangers that arise when the interface between strategy and operations is unclear.[10] The solution is better operational art, not the abolition of the operational level. Similarly, criticism that the operational level displaces civilian control overlooks the doctrinal reality that operational-level command remains under civilian strategic direction.[11]

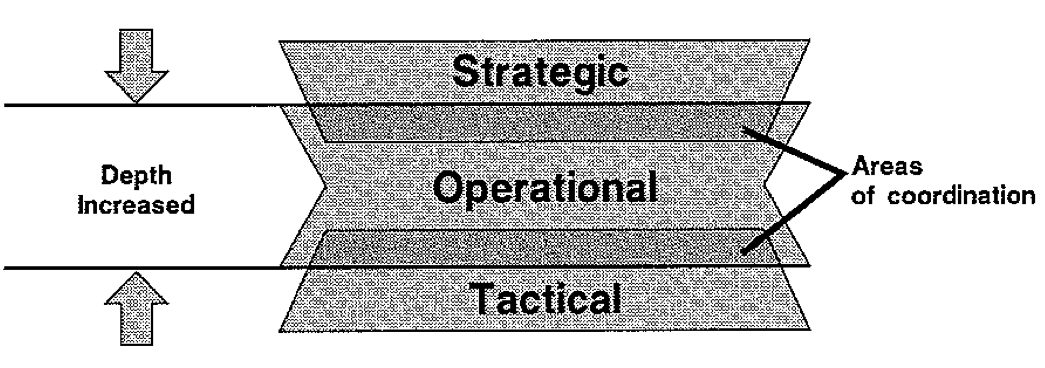

Source: Image from The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters[12]

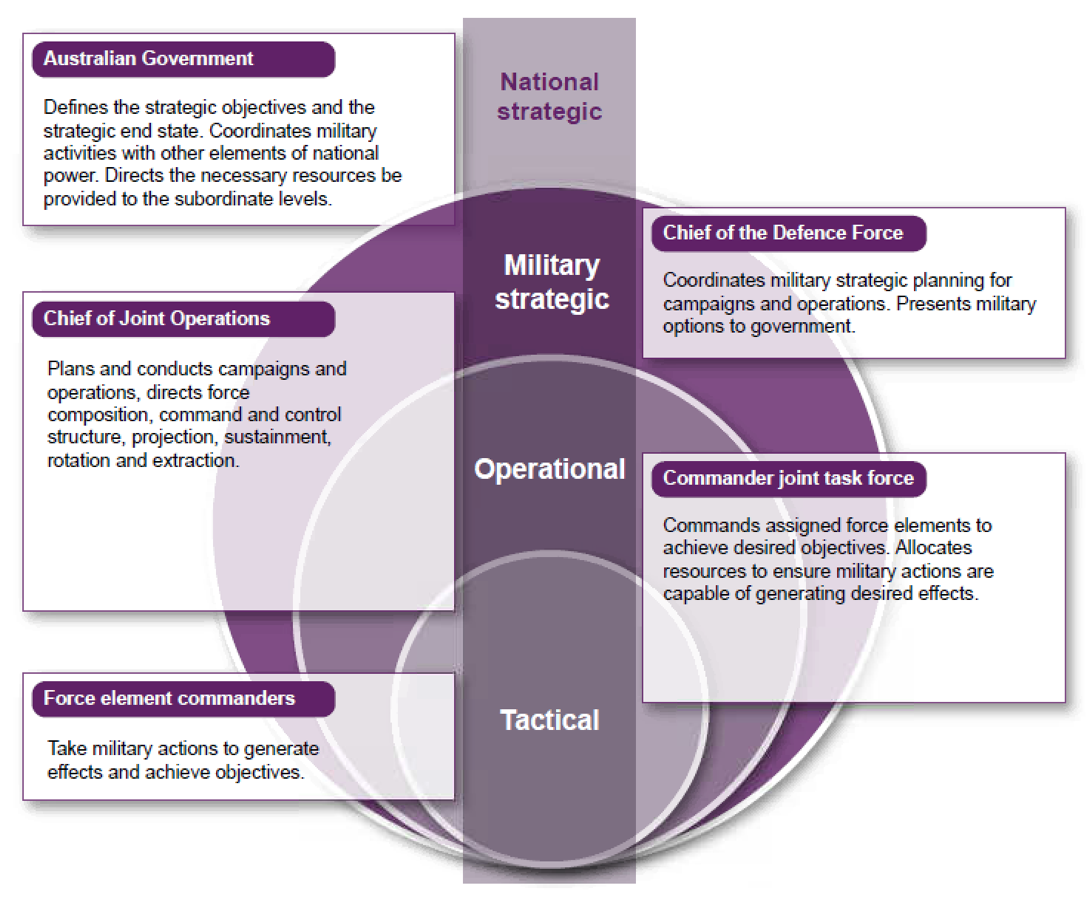

This post’s primary contribution lies in proposing a way to better visualise the dynamic interplay between levels of war while locating operational art within the broader strategic-tactical continuum. Historical diagrams (i.e. Figure 1) present the operational level as a rigid, hierarchical intermediary between strategy and tactics, suggesting limited interaction or overlap. Recent Australian doctrine has improved on this by demonstrating nested levels, as seen in Figure 2. However, this depiction still fails to encapsulate the synchronous and temporal pattern in which multiple lower levels of command may operate within the same strategic confines.

Source: Image from ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power, Edition 2[13]

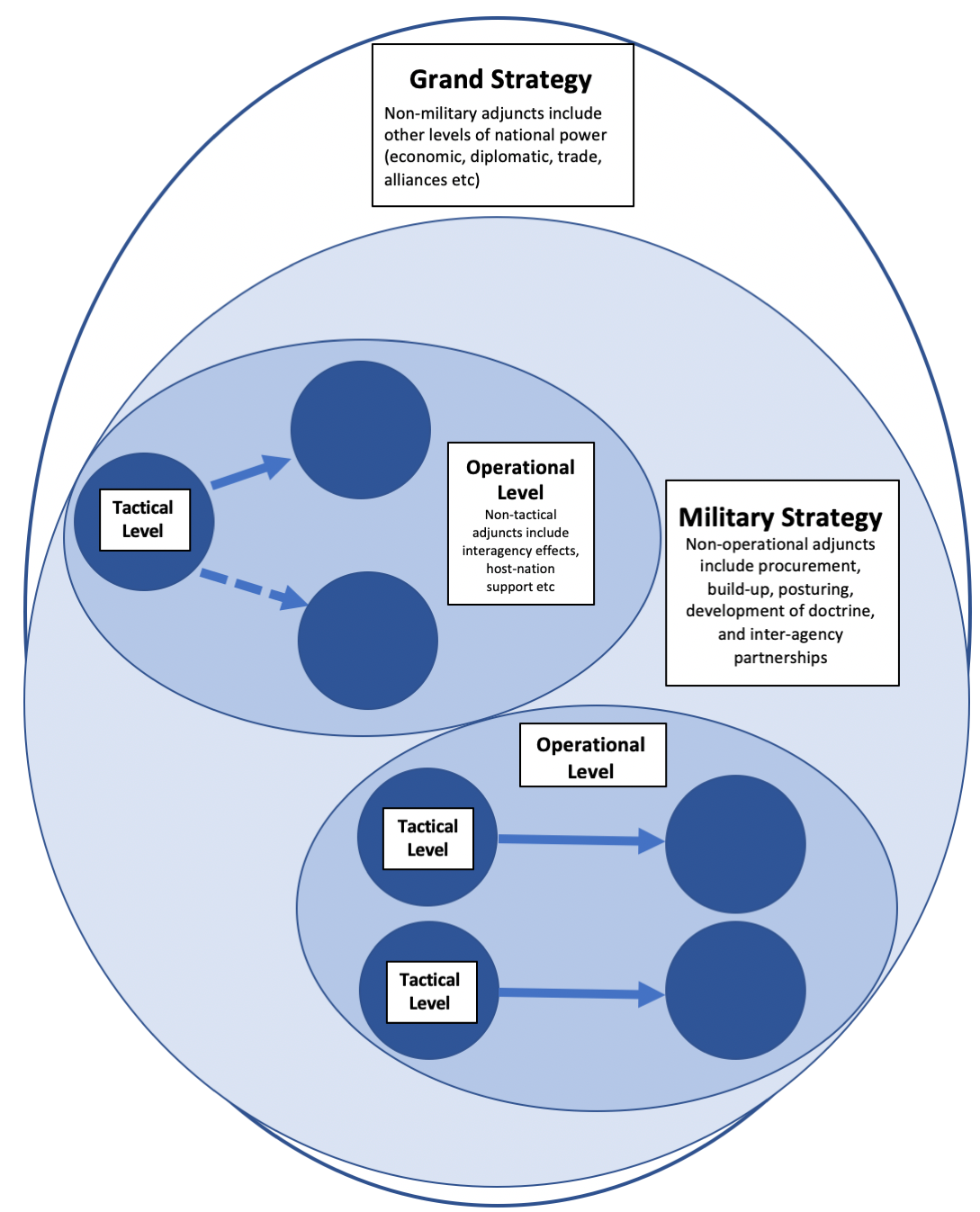

The diagram presented here (Figure 3) seeks to remedy this by showing the operational level to be dynamically nested within broader strategic contexts, explicitly accounting for temporal and geographic variability. Furthermore, it depicts simultaneous, overlapping tactical operations within a unified strategic framework, highlighting how tactical actions can influence strategic decisions and vice versa. Arrows indicate temporal progress, and the interstitial space represents the adjunct activities (e.g., information operations, diplomacy, economic measures) that planners at all levels must account for. Additionally, it visually represents the integration of non-military adjuncts (such as, at the operational level: interagency effects or host-nation support) being executed within the interstitial space that sits separate to the various tactical levels. In doing so, it enhances coherence and strategic alignment across the whole.

Implementing this refined conceptualisation offers tangible benefits to the Australian Army. Firstly, it enhances clarity and integration across command levels, providing a practical tool for commanders and staff officers to visualise and manage complex operational realities. Secondly, it supports improved synchronisation in coalition operations and campaign design, by explicitly demonstrating how Australian-led tactical and operational initiatives align with broader strategic coalition goals. In an era characterised by rapidly evolving security threats and coalition-dependent responses, this model equips the Australian Defence Force to exert strategic influence more effectively and responsively.

In conclusion, while the operational level of war may be justifiably scrutinised, abandoning it would overlook its fundamental role in bridging strategic intent and tactical execution, especially for a middle power like Australia. To address this, first of all, the operational level of command and operational art must be disentangled conceptually. Secondly, the operational level needs to be reconceptualised to enhance its relevance and practical utility. By adopting the dynamic, nested framework proposed in this post, the Australian Army can address existing doctrinal shortcomings, better support the achievement of strategic clarity, and enhance operational effectiveness. This approach ensures that the concept of the operational level is not reduced to a set of labels, but is instead recognised as a vital analytical and organisational tool for navigating the complexities of contemporary warfare. In this way, it makes a valuable contribution to Australia's strategic preparedness and regional leadership.

Endnotes

[1] Australian Defence Force, ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power Edition 2, (2024).

[2] Will Viggers, "Politics, Strategy and Tactics: Rethinking the Levels of War", Australian Army Journal 16, No. 1 (2020).

[3] Tom McDermott, "Letters from HAMEL Part 3: The Operational Level of War. What is it Good For?", Grounded Curiosity (2016), https://groundedcuriosity.com/def-australia-letters-from-hamel-part-3-t….

[4] Martin Dunn, "Are the Levels of War Just a Set of Labels?", The Cove (31/07/2017 2017).

[5] Viggers, "Politics, Strategy and Tactics: Rethinking the Levels of War".

[6] McDermott, "Letters from HAMEL Part 3: The Operational Level of War. What is it Good For?".

[7] Dunn, "Are the Levels of War Just a Set of Labels?".

[8] Paul Cheng, "Decisive Battle and Operational Art: Contradictory or Complementary Notions?", The Forge War College Papers 2020 (2020).

[9] Tanya Evans, "Are operational level functionality and operational art viable concepts for Australia, or any other middle power?", The Forge War College Papers (2020).

[10] Alex Vohr, "The Operational Level of War Does Not Exist", Marine Corps Association (2024).

[11] McDermott, "Letters from HAMEL Part 3: The Operational Level of War. What is it Good For?".

12Macgregor, Douglas A. 1992. “Future Battles: The Merging Levels of War”, The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters.

[13] Force, Short ADF-C-0 Australian Military Power Edition 2.