Abstract

Simply being aware of cultural ‘dos and don’ts’ is insufficient to ensure truly gainful cooperation with a host populace, especially when the Army is waging counterinsurgency campaigns in complex, urban battlespaces. Taking cultural awareness ‘to the next level’ is the subject of this article, which details lessons from the Army’s arguably expert force regarding this topic: the Regional Force Surveillance Units (RFSUs). The authors examine the major aspects of the RFSUs community engagement strategies to highlight how the hierarchically-based Army has adapted itself to better integrate with the unique mix of traditional social groups resident in the north of Australia. In so doing, the authors reveal the many inroads to mission success that can be made by working with—rather than around—local civilian populations.

Introduction

Modern demographics suggest that conflict will increasingly occur in populated centres rather than uninhabited fields. As a result, people in contested areas—both combatants and civilians—will increasingly shape future battlespaces. Whether acting as an outside intervention force or as an integrated ally and partner, modern militaries must improve their capability to work with, and within, populations. The need for this has never been more clear than it is today in conflicts such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

Despite the increasing need for interaction with local populations, security planners and military forces may underestimate or dismiss community engagement as a task more appropriate for civilian agencies. This article seeks to articulate the value of engaging rather than circumventing communities, and suggests ways to navigate cultural complexities and inter-communal sectarianism. In doing so, it draws lessons from the Australian Army’s security partnership with its own indigenous communities.

Three units in the Australian Army, known as Regional Force Surveillance Units (RFSUs), are responsible for the surveillance of the country’s northern approaches and identification of border incursions by smugglers, illegal fishing vessels, and other potential threats. This mission, known as Operation RESOLUTE, relies heavily on the participation of indigenous reservists recruited from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. These reservists contribute extensive knowledge of the remote, difficult terrain of northern Australia, and they can facilitate Army operations in traditional lands from which outsiders are otherwise restricted.

The RFSU model is a useful case study for militaries who seek to engage better with populations that are culturally centred on community, family, tribe or clan relationships. This article reflects observations made during a one-month period spent with the 51st Far North Queensland Regiment (51 FNQR), which operates in the north-eastern Cape York and Torres Strait regions. In the course of extensive interviews with both indigenous and non-indigenous soldiers, we observed the methods by which 51 FNQR interacted in a mutually beneficial way with its indigenous population.

This article will discuss six key areas in which modern military units can learn from the RFSU experience. These include: identifying common security interests between populations and security units; developing positive relationships between indigenous communities and the Army unit; basing operations on cultural awareness; and, finally, the baseline assessment of 51 FNQR’s experience in mitigating tribal/clan tensions to instruct broader methods for navigating sectarianism in population-centric environments.

Community Power Structure

The Australian Army has long recognised the concept that domestic stability requires a shared commitment between the national and local security forces and local populations; as most recently shown by reporting of Australian operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Whether a national security force or a local community organised along tribal lines, both systems are organised by unique power structures. In order to support a common national security agenda, both systems must work together, although this goal is often difficult to implement due to conventional civil–military frictions and can be further complicated by cultural and language barriers. The ways in which 51 FNQR soldiers engage local communities by coordinating with municipal and tribal leaders is instructive for any military facing the challenge of operating in a foreign environment and where local support or concurrence is critical to the success of a national security mission.

A security force operating in close proximity to civilian communities must identify, respect, and reinforce existing power structures in order to achieve a unity of effort, rather than struggling to achieve a unity of command. By recognising the complex layers of leadership and authority that can exist in an indigenous community, the officers operating in local areas come to appreciate that authority may not lie exclusively in official office bearers. 51 FNQR understands the importance of gaining the support of existing community power structures in order to support their missions of recruiting, tactical patrolling, and regional stability. This is particularly imperative in indigenous communities, where traditional power structures have much more influence over a society than a term-elected municipal leader.

A significant challenge of any military operating within the general population is the extent to which security forces can engage the communities. A highly regimented organisation itself by tradition, it is often challenging for a military unit to relate to a friendly foreign force on a truly bilateral basis. More difficult, and less understood, is how a military unit can operate in a tribal society, where the local power structure may not follow a more regimented or formal Western model outlining authority; tribal elders may not keep regular business hours from a professional office; leadership and authority may be expressed in unfamiliar ways; and, similarly, an outsider’s authority may not be immediately accepted. A military unit commander’s rank may hold no value for a tribal community, thereby complicating the protocol with which that unit may gain support or coordination from a local community. Therefore, it is essential for those in uniform to understand how locals perceive security forces, how locals understand authority, and the degree to which the military’s authority can work in cooperation or in conflict with local power structures.

The 51 FNQR area of responsibility encompasses dozens of indigenous communities, each with its own distinct customs, dialects and authority figures. We observed that community leaders appreciated being consulted by 51 FNQR company commanders for their coordination, rather than having the soldiers being overly focused on a specific operation and therein dismissing the local population. Furthermore, traditional elders valued RFSU recruiting efforts in the community. Although this support was not always manifest in high volunteer rates, the elders’ long-term view on partnering with the Army acknowledged that components of regimental service can benefit the communities; traditional leaders’ status was reinforced as Army liaison and local enlisted soldiers return to their communities more confident, better organised, and ready to assume greater local leadership positions. At a time where traditional leaders are concerned about the erosion of their communities from external modern influences, the RFSUs have presented timely and relevant opportunities that benefit the communities far beyond local recruitment or security operations.

Perhaps the most important way 51 FNQR shows its willingness to work with the needs of the local community is that reserve service allows locals to take ownership for putting on and taking off the uniform; part-time, professional military service requirements do not create cognitive problems for indigenous soldiers by subjugating local identities to a broader national identity. Through voluntary enlistment and reserve service, indigenous soldiers have the opportunity to regularly return to community life and resume traditional identities. As the RFSU reserve commitment is twenty days of service per year (although most elect to serve an average of 100–180 days each year), indigenous soldiers have a great deal of flexibility in being able to balance their national service and community commitments. Community leaders appreciate that the Army is not trying to rival or usurp traditional leadership structures. Furthermore, by including a role for indigenous civilian ‘liaison’ to work with RFSU companies, 51 FNQR leverages a variety of creative tools to secure linkages with the local authorities and guarantee concurrent support for the national security objective of denying sanctuary to those conducting illegal activity in remote areas.

Ideally, a military commander would have institutional knowledge of a community. This could include cultural awareness training, familiarity with local residents, or unit members from the local area who can serve as important liaison for civil–military relations. More likely, the unit leader will be the first point of contact with a community, and lack the requisite anthropological skills and long-term outlook to cultivate a relationship once the crisis that mobilised the military unit occurs.

Community Relations

In addition to the leaders’ knowledge and attitudes, it is essential that rank and file soldiers also appreciate their relationship to both local power centres and the broader community in order to coordinate a common response to security threats. As RFSU units are small and have a relatively flat chain of command, the role of the ‘strategic corporal’1 is highly relevant to regular interactions with local communities. For the RFSUs, positive relationships with the local communities in their areas of responsibility (ARs) enforce common security priorities, such as reporting illegal fishing, trafficking, smuggling and immigration activities. With a small force and limited resources, the RFSU soldiers cannot possibly provide a constant patrolling presence throughout the remote northern territories of Australia. Instead, they rely on partnerships with local communities to provide critical intelligence and reporting on area activity.

As US Army General Charles Krulak observes, it is increasingly likely that soldiers will have to react to and interact with local populations at low-levels of command and organisation.2 Balancing the desire to cultivate or maintain community support for military operations while avoiding political situations that could complicate a mission is challenging. The fundamental task of engaging a community can be further complicated when a military and local population cannot readily relate to one another. Krulak suggests that each military unit’s leader must possess agility to navigate these complex scenarios. How that leader understands a community that is often inextricable from the battlespace is vital, and it is in this knowledge area that 51 FNQR excels.

To develop these relationships, 51 FNQR company commanders draw on their professional agility to overcome common challenges to developing relationships in traditional or tribal communities. As described in previous sections, cultural differences between the Army and traditional community styles can create friction in the establishment of operational authority, as company commanders must reconcile their responsibility for executing 51 FNQR’s area mission in conjunction with local community leaders’ concurrence.

In a broader sense, positive community relations can support the RFSU’s missions more effectively than an increase in number and frequency of unit patrol operations. Army soldiers sceptical of the RFSU’s value as something more than ‘political window-dressing’ suggested that the remote surveillance and reconnaissance missions could easily be conducted by small units of regular soldiers, without the need for engaging local communities and modifying enlistment criteria to allow for greater indigenous participation. Dismissing this claim, one 51 FNQR company commander explained that while soldiers might be attracted to the notion of covert patrols through the bush, with full camouflage face paint and full kit, 90 per cent of his most valuable surveillance information came from the communities. More than the surveillance patrols, community engagement missions that included local recruiting and public relations components were highly valuable and yielded even more important results. He explained that as community engagement could not be easily evaluated by conventional metrics, it was difficult for some of his colleagues to understand the value of civil ‘missions’, but that they were just as critical to the broader goal of regional security and stability as were the bush patrols. With limited resources, the company leadership can dedicate most material assets to conducting remote patrols while community engagement requires little more than the commitment of several RFSU soldiers to spend several days in a community for recruiting and leadership engagement events. In that way, community engagement could be undervalued by decision-makers as it does not require a significant dedication of conventional resources for successful execution, but it is for this very reason that community engagement serves as a critical force multiplier, as is evidenced by the increasing role of human terrain and provincial reconstruction teams working to secure local support in the Iraq and Afghan theatres.

Looking beyond annual metrics and requirements, the company commander (a major) understood that community engagement requires both legitimacy and credibility to work over the long-run; soldiers cannot simply roll into town and expect results. For reconnaissance and surveillance missions, patrol and community engagement operations focus on identifying change in the security landscape over time, rather than absolute change. This is to say that the missions require a regional sensitivity that cannot be statically conveyed in a pre-deployment briefing, but rather developed by operating in the field and engaging with local residents over time. For this reason, several junior and senior company leaders stated that community engagement requires a ‘365-day a year’ approach. Rather than suggesting that the Army could or should be physically present at all times in every community, it means that the military should ensure that the many means of engaging local communities are being properly employed.

Cultivating a civil–military relationship requires a great deal of personal engagement, but it is critical that general community engagement remain broad in focus to withstand personnel changes in the long run. The challenge of this task is reconciling the long-term roles of community leaders with the more transient two-year assignments for RFSU company commanders in the field. These officers in charge face the task of cultivating, or stewarding, a relationship with community leaders, but—as discussed above—cannot always rely on their rank as a means of entry into the community’s leadership circle. Faced with the challenge of having to establish a bond with civilian leaders, an officer may be tempted to present himself as a friend.

However, doing so compromises the integrity of the RFSU’s mission. Some indigenous enlisted soldiers in the RFSUs (who are assigned to RFSUs for their entire careers),3 complained that an incoming officer in charge would sometimes try to present himself as the company soldiers’ best friends—an approach interpreted as not taking the indigenous soldiers as ‘seriously’ as non-indigenous Australian soldiers, who were held to different standards. Critical to achieving a long-term framework for cooperation and collaboration against foreign exploitation and infiltration of remote areas is appreciating that community engagement, at all levels, must be something greater than a series of interpersonal networks. In this way, community engagement cannot be limited to leadership partnerships or liaison billets, but involve a broader, community-based support for interaction and collaboration—in the military, political and local communities.

A key challenge to maintaining steady community relationships is that of turnover. In any military setting, including operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, units and leadership will invariably change every few years or less. However, there must be an effective way to maintain continuity in relationships with community leaders, the soldiers, and the community itself. As difficult as it may be logistically, a period of overlap between company leadership would permit more stable relationships with local leaders. Detailed changeover documents and introductions to community leaders would facilitate this process, but are not enough. Cultural adjustment is required for the leaders, and having overlap between leadership changes would save a significant amount of time that would otherwise be spent in adjustment.

Community engagement is not about completing a checklist of office calls and photo opportunities, but rather constantly building and reinforcing a framework to support the larger security mission. As with many introductions, the military and the community likely have preconceptions about one another, some of which may be inaccurate. This is particularly true when the two groups seldom associate with each other. 51 FNQR soldiers and officers acknowledge that there are misperceptions among outsiders of what life is like in indigenous communities. Infrequent media coverage tends to highlight the extreme stories of abuse and malfunction, and 51 FNQR soldiers are quick to demonstrate their interest in taking the time to get to know the locals and understand the needs of the community rather than assume that they understand the particulars of a community based on its public reputation. For over two decades the Australian Army has worked to establish relationships in remote indigenous communities, but the work in this area is far from complete.

Indentifying Common Interests

One of the key reasons for the RFSU’s success is its focus on an issue of mutual interest between indigenous communities and the Australian Army: border security. Like many indigenous societies, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities deeply value their ties to traditional lands, and their rights to the resources within them. In many cases, Aboriginal landowners have the power to grant or deny outsiders the right to enter traditional land, and to hunt or fish on those lands.

Federal agencies seek to defend the Australian homeland against illegal immigration, strict quarantine regulations, natural resource exploitation, and illicit smuggling activities. Given the situation of indigenous control over many of Australia’s most remote and vulnerable areas, it is critical that those responsible for national security have the capability to leverage all defensive measures necessary in a way that remains in concert with its citizens’ traditional ways of life. This mutual security interest—protection of Australian lands, borders, and resources—provides an opening for 51 FNQR to collaborate with local indigenous communities on immediate, practical issue areas. In any population-centric environment, military planners should prioritise the task of identifying common areas of interest between local groups and security forces. By doing so, the security forces (including the military) are able to secure a strong baseline on which they can execute more complex operations.

It is also useful to note that trained, skilled soldiers are also trained, skilled community members. 51 FNQR trains its reserve soldiers in communications, remote area driving, boating, patrolling and more. RFSU service provides opportunities for indigenous reservists to develop both professional skills, such as welding or carpentry, and important leadership skills. The RFSUs do so because the commanding officers and senior community leaders recognise that such skills will enhance economic and civic opportunities for the communities involved. These skills raise the confidence and status of reservists within their communities and, as a result, the communities often view the Army as a venue for skills development and as a means to enhance their capabilities as individuals and communities.

Therefore, military commanders in population-centric military operations should carefully consider how to align a military unit’s goals with those of a target community. They should develop and utilise sound cultural knowledge and listen to the needs of community members. By identifying answers to key preliminary questions about local security problems and socio-economic priorities, a unit can fine-tune its approach to local communities, thereby being able to move beyond burdensome and often shallow ‘hearts and minds’ public affairs campaigns.

Draw on Local Resources

The first instinct of militaries operating in population-centric settings may be to underestimate the resources that can be provided by the community. This would be a grave mistake. With thought and creative implementation, community resources can be mobilised effectively to complete almost any mission. In the 51 FNQR AR, we observed three key resources that the community itself provided: valuable recruits with skills unavailable elsewhere; operational intelligence; and local civilian liaison to mitigate the friction that naturally arises between the Army and local communities.

51 FNQR was particularly effective at tailoring its recruiting practices to the concerns and needs of potential indigenous soldiers, to draw on the pool of recruits in the ARs. The Army enforces rigorous literacy, numeracy, and health standards in its recruiting efforts, but the RFSUs acknowledge that these standards may disqualify many indigenous recruits with great potential to contribute to the RFSU mission. The Army’s RFSL, therefore, allows commanding officers to waive specific enlistment criteria in order to employ indigenous reservists in a regional capacity in Cape York and the Torres Strait.

Recruiters were aware that potential recruits may have developed misperceptions of army life based on media portrayals. Only through awareness of this problem can recruiters mitigate this area of concern, demonstrating that RFSU operational tempo was more closely related to indigenous hunting excursions than what is displayed in Hollywood films such as Full Metal Jacket. Another issue that RFSUs could respond to was from their indigenous recruits’ worries that they would be required to travel far from their home communities, that training officers would treat them harshly, or that their reservist status would have a negative impact on their unemployment compensation. Well aware of the image of the stereotypical soldier, recruits also feared the embarrassment of failing to meet basic qualification standards. Recruiters received useful cultural training that helped them understand these worries—many of which are culturally-based—and these recruiters built on this preliminary knowledge by working with indigenous community leaders and indigenous soldiers to find creative solutions to temper these potential points of friction.

Once strong relationships existed between the Army and the communities, the encouragement of family members, friends, community elders and council members strongly influenced recruitment. When arranging recruiting or outreach missions, officers in charge tended to select those indigenous reservists with strong ties to the targeted community. After arriving in the community, officers instructed these reservists to take the lead in reconnecting with family, friends and other contacts in the communities. This approach provided many benefits, including a better perception of the Army, enhanced trust-building and increased likelihood that potential recruits would indulge their curiosity and approach recruiters. Furthermore, a strong emphasis on interaction with community elders helped gain the support of influential community members who guide community youth toward the Army.

Another key to the RFSU’s success is its emphasis on intelligence and information gathering by local communities. Valuable intelligence can be extracted from an avenue other than the formal border security and surveillance missions of the unit. This local intelligence helps prevent military planners from falling into the trap of mirror-imaging, in which planners may miscalculate assumptions and thereby compromise the ability to meet a mission successfully. In population-centric operational environments, situational awareness and cultural awareness are not mutually exclusive, and by drawing on critical information passed from indigenous sources, planners are in a better position to develop a robust picture of their area of responsibility.

A major challenge to communitycentric engagements is effective communication with local populations. In response, RFSUs often draw a third critical resource from local communities: mentors and liaisons that can enhance communication between indigenous officers and non-indigenous soldiers. In places like Iraq and Afghanistan, where indigenous populations serve as the backbone for police and military forces, communication in support of training efforts becomes especially important and difficult.

Mentors were particularly helpful during the Army Aboriginal Community Assistance Program (AACAP)—an annual effort to provide improved housing/infra-structure, promote health, and train select community members in valuable skills that can be applied in local industry. The training program was structured in small four-person teams, including a regular Army trainer, two community members, and one indigenous reservist (often a more experienced non-commissioned officer). The indigenous reservists were identified as ‘mentors’ because previous experience working with non-indigenous officers enhanced their ability to facilitate communication within the group, approach the Army trainer to address issues that might otherwise go unnoticed, act as a role model for community members, and provide valuable advice from the perspective of a successful reservist.

Using local resources to support communication, intelligence, and force skill development is not only a cost-effective solution to overcoming familiar operational obstacles, but it also serves to create a substantive bond between the military and indigenous groups sharing a common operational area. Using local resources—rather than importing skills and services from special teams or contractors—has a significant force multiplier effect at the strategic, operational and tactical levels.

Navigating Sectarianism

The challenges facing multinational forces in Iraq and Afghanistan highlight the negative impacts civil sectarianism can have on implementing a common security policy. Without a nation-wide consensus on and support of a security agenda, regional or inter-communal enmity can derail any attempt to implement a common program. Establishing and guaranteeing homeland security is particularly challenging in these scenarios, as inter-communal rivalries can create incentives for profiting from cross-border illicit activity, territorial competition, and general blockades to state-supported commercial traffic and security patrols.

Not only does sectarianism threaten security on a national level, but it can also undermine the effectiveness of security organisations themselves. Sectarianism can undermine authority, cooperation, and the mission of a security strategy by stoking divisions and competitions among communities or against the larger state. Tribal societies are more likely to display sectarian tendencies, as their traditional structure does not always readily conform to modern social conventions, such as pluralistic nationalism. As we continue to observe in Iraq and Afghanistan, traditional communities may not prioritise central government programs for border security, which may exclude certain customary interactions with neighbouring communities from different states. For this reason, it is especially important that national security forces identify and implement creative solutions to engage border area communities in a cooperative security framework. Although Australia does not have internal conflicts to the degree that exist in Iraq and Afghanistan, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities throughout northern Australia maintain unique traditions and objectives which, at times, clash with national law enforcement and other government services.

As already discussed, 51 FNQR companies work to gain the trust of and coordination with indigenous community leadership to coordinate operations. Equally important to achieving this objective is the way that 51 FNQR soldiers navigate sectarianism within the unit itself. Not dissimilar to the challenge of recruiting a national force from across tribal societies in Iraq and Afghanistan, the RFSUs must confront and overcome potentially divisive issues when working in the indigenous communities whose tribal affiliations are far from homogenous.

Recruiting from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the Australian Army acknowledges the unique environment it is creating for its soldiers. The 51 FNQR draws individuals from remote, heterogeneous, tribal communities and trains them to perform as a soldier, with all the expectations and requirements placed on Army reserve enlistees. However, the RFSUs recognise that the indigenous enlistee faces greater obstacles to fully integrating into the reservist program. Coming from cultures in which staying away from home for prolonged periods of time is a rarity, indigenous soldiers can find it difficult to complete training courses or remote reconnaissance operations. Additionally, certain indigenous soldiers are confronted with tasks that challenge their traditional taboos, such as crossing certain terrain, interacting with ‘poison’ members from other tribes, or taking command over other soldiers whose tribal social status might be higher than that of the commanding officer by Army standards. As a soldier and member of the unit, tribal differences, traditional taboos, and other sectarian behaviour will not be tolerated within the ranks. To emphasise this point, the RFSUs have developed a ‘One Skin’ policy, by declaring that the green uniform is a common ‘skin’ for all soldiers. All those who choose to put on the uniform also choose to put aside racial, tribal or other differences. The single army-green ‘skin’ covers any differences between indigenous and non-indigenous soldiers.

The important One Skin policy not only works to resolve intra-service sectarian issues, but intra-communal differences as well. While semi-autonomous indigenous communities may compete with one another for resources, it is important that the Australian Army soldiers operating in these communities maintain a neutral reputation. Whereas local leaders described certain social service and law enforcement agencies as acting autonomously of the communities to which they are assigned, they characterised 51 FNQR as being exceptionally willing to work with local communities in ways that respect local customs and balances of power. This professional neutrality extends to inter-community relations, in that local communities did not feel as though certain tribes were favoured by or received disproportionate benefits from the local Army companies.

Furthermore, 51 FNQR leadership demands that their soldiers respect the One Skin policy with reference to civil–military affairs to prevent the companies from being ‘ethnicised’ or otherwise distinguished by a certain tribal affinity. While the current RFSU soldier roster does not represent every indigenous community in the 51 FNQR AR in Far North Queensland, the Army and community leadership acknowledge that this is a long term project. Even if this representative diversity was achieved, the One Skin policy is applied in a civil affairs context as promoting an exclusive Army ‘profile’ that supercedes any other tribal affiliations. Not wanting a certain tribal group to assume that their relatives will demonstrate preferential treatment to their needs or similarly perpetuate sectarian aversions to taboo communities, the public version of One Skin provides a mitigating, neutral cover for moving among divided communities.

The Australian Army seeks to navigate the potential operational trip-wires of civil sectarianism by training their soldiers for cultural agility and reinforcing both unit cohesion and professionalism through the One Skin policy. This model addresses not only the battle to secure hearts and minds, but also the cultivation of common security priorities to bring soldiers from communities rife with sectarian divisions and cultural barriers together in a single unit tasked with implementing regional security priorities.

Conclusion

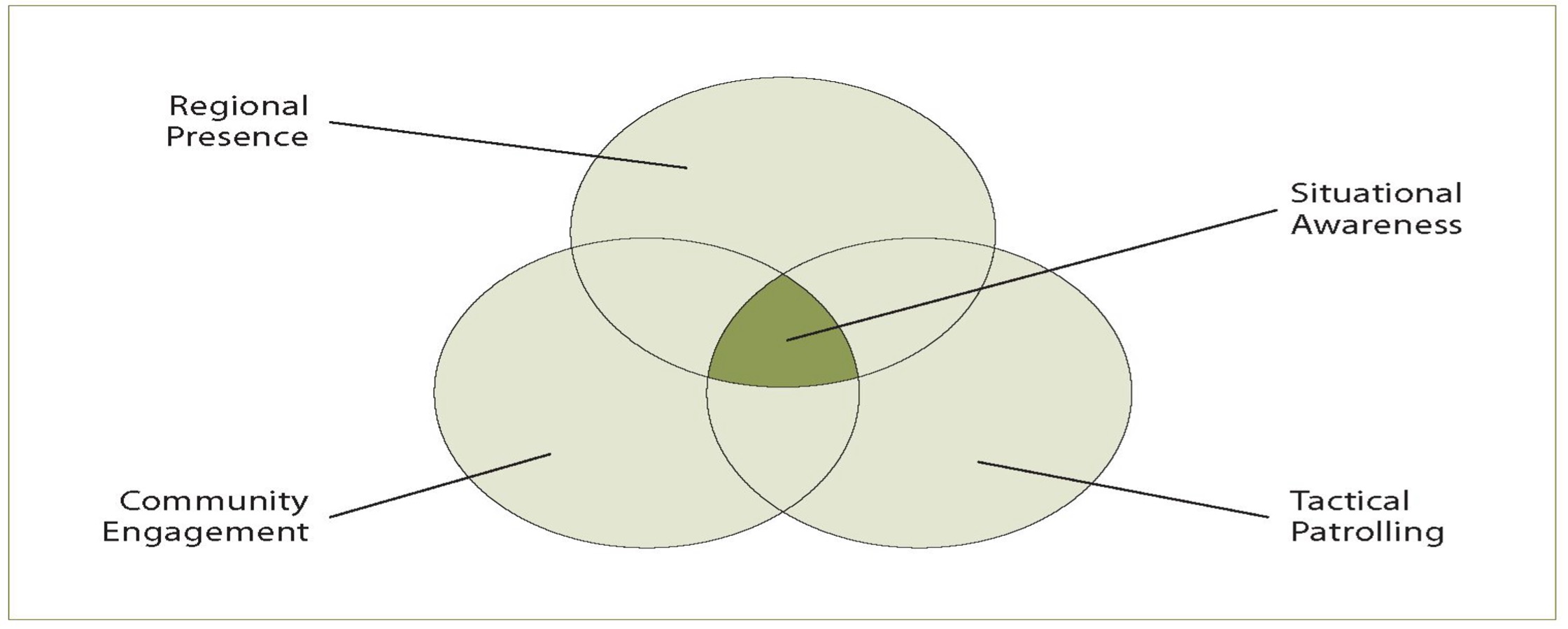

The multifaceted mission of the RFSU is perhaps best summed up by a set of concentric circles (Figure 1) described by one of the 51 FNQR officers.4 One circle represents the tactical patrolling mission (Operation RESOLUTE), another represents the community engagement and assistance activities run by the unit, and a third represents the broader effort to maintain a positive regional presence. Only by using all three of these tactics can the RFSU achieve true situational awareness—a fundamental requirement for any successful operation.

Critics of the RFSUs suggest that Operation RESOLUTE can be accomplished without indigenous reserve units; that is, by regular full-time soldiers trained for remote surveillance and reconnaissance. Indeed, Army regulars could likely maintain patrol mission tempo. But this approach ignores two of the three ‘circles’; simple tactical patrolling is not sufficient for long-term success, as we observed in our time with 51 FNQR. It is critical that the value of community engagement should no longer be dismissed by defence forces as the realm of civilian agencies, but rather incorporated as a key tool to accomplish military missions. Additionally, maintaining a regional presence provides a greater ability to deduce nuanced changes over time rather than simply identifying absolute changes that vary between patrol operations in the theatre.

Current war planners in Iraq and Afghanistan are beginning to consider the force multiplier effect that supportive local populations can have on their operations, and the RFSU experience highlights the impact of such a multiplier. This effect may manifest in a reduced need to employ personnel to counter opposing forces, or it may become apparent in an increased pool of resources arising from contributions from a willing community. When military units develop persistent relationships in a community, they are more likely to benefit from on-the-ground intelligence. Locals may be more inclined to facilitate operations, or at least to refrain from impeding them. Using the metaphor of a three-legged stool for 51 FNQR’s tactical components, while reconnaissance and surveillance patrols prop up the most apparent or measurable part of the overall security mission, these patrols alone could not withstand environmental pressures or unforeseen crises that could tip the balance and negate previous tactical successes. All of these factors allow troops to focus on fighting foreign enemies, preventing enemy infiltration, provide security that supports infrastructural and economic development, and promote conditions that encourage opportunities to develop a robust corps of indigenous soldiers.

Figure 1. The multifaceted mission of the RFSU

Military planners must recognise that, for better or worse, situational awareness requires a longer-term approach, for community engagement and regional presence cannot occur in a week or, perhaps, even during a two-year tour. The RFSU model allows commanders to expend the needed effort to build situational awareness, understand a community’s power structure and priorities, and identify common security goals. It allows units to develop culturally-based practices in a setting where cultural ‘sensitivity training’ is simply not enough, even when supported by the best cultural anthropologist or area specialist. Furthermore, it increases the likelihood that security planners can develop appropriate metrics for success and appreciate nuanced, less tangible changes that may otherwise go unnoticed.

Given an emphasis on relationships and the importance of a longer-term approach, leadership transitions must be carefully executed. RFSUs struggled with continuity during transition of commanders, who rarely overlapped with their predecessor long enough to be introduced to community leaders. Any exiting commander should be provided opportunities to pass information, make introductions, and ‘be seen’ with his or her successor. And new commanders will need to temper their enthusiasm for change with recognition that continuity also can be valuable.

The flexible nature of RFSUs allows commanders to gain the trust of indigenous populations and find creative, culturally-based solutions when needed. Military planners should recognise the value of this flexibility when working with communities, and the inherent need for multiple options and approaches to improving regional security. Although this is changing, default tactical plans may rely on conventional military manoeuvres, leaving unit commanders with few options to meet the emerging operational challenge of engaging civilian populations. This needs to change, and recent changes in how coalition forces are approaching challenges in Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrate the ways in which senior policy-makers and military planners are rethinking the tools available to their combat elements facing operational challenges. With this trend, it is important to acknowledge successful models, such as that of the Australian Army RFSUs, in developing dynamic and comprehensive approaches to operational challenges in population-centric theatres.

We found that 51 FNQR recognised, and acted upon, the inherent connection between strong community relationships, perceptive cultural engagement, and achievement of the national security mission. In part because of this approach, 51 FNQR enjoys a status as a positive, respected force in the communities it engages. Downstream benefits—including enhanced situational awareness and threat reduction—makes the unit far better able to meet its security goals.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the US Government.

Endnotes

1 Charles C Krulak, ‘The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War’, Marines Magazine, 1999.

2 Ibid.

3 For a variety of reasons, most indigenous recruits select to enter the Australian Army through the Regional Force Surveillance List (RFSL) program, which restricts service options to within the three RFSUs in northern Australia. This restriction is often insignificant to most RFSL soldiers, as they generally prefer to serve in their local communities.

4 Major Doyle, Officer Commanding A Company 51 FNQR provided this description, crediting Lieutenant Colonel Chris Goldson with having provided the original illustration.