Abstract

This article explores the ways in which the Australian Army’s 1st Reconstruction Task Force, deployed to Afghanistan in August 2006, implemented complex adaptive systems theory to develop an adaptive approach to their role as part of counterinsurgency operations.

For highly complex missions, it is not realistic to expect to “get it right” from the outset. The initial conditions are much less important than the ability to improve performance over time.1

Contemporary counterinsurgency operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, southern Thailand, and the southern Philippines have proven a significant challenge for those nations whose military cultures and force structures are still evolving from Cold War, conventional mindsets. It is likely that state militaries will continue to face such challenges as insurgency continues to be the favoured approach of violent non-state actors. Therefore, success in these operations will be determined largely by the ability, and willingness, of Western forces to adapt and thrive in the changed situation.

The character of the operation in Afghanistan reflects that of many previous insurgencies, with the addition of contemporary influences such as pervasive media. Recently described by Hoffman as a neoclassical insurgency2, the Taliban and al-Qaeda forces possess a cause, effective leadership (based in Pakistan3), support from (at least part of) the population, favourable terrain and external support as well as a sophisticated ability to manipulate the Internet and mass media to influence perceptions.

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the insurgency is its proven capacity to adapt, not only to the terrain and the operations of counterinsurgents but also with its application of new technologies to their operations. Ten years ago, the Taliban did not permit the playing of music; now it is highly adept at exploiting multimedia for its propaganda in Afghanistan and around the world. These factors combined make Afghanistan a serious challenge for conventional Western military forces and a destabilising influence in the region. While this lethal conflict will require time and resources to confront, as history shows it is possible to defeat insurgencies and Afghanistan is no different.

This paper examines how the 1st Reconstruction Task Force (RTF) implemented a systemic adaptive approach, not as a new method of operating, but to improve the chances of the unit successfully influencing its environment. Military commanders have always sought to innovate both during and between conflicts to ensure success. Therefore the efforts of 1RTF to innovate and develop new ways of doing business are not exceptional. What does set these operations apart is the deliberate use of complex adaptive systems theory as the framework for implementing an adaptive approach as part the unit’s culture.4

In reviewing 1RTF’s implementation of an adaptive approach, this article starts with a description of the context—how reconstruction operations fit within counterinsurgency campaigns, and the environment in which the task force operated. The next section describes how the task force sought to win the adaptation battle against the Taliban. Further, this article offers suggestions on the transition from theory to practice in the conduct of systemic adaptation5 before and during military operations. The underlying principle, implemented from the top of the organisation, was that of winning the adaptation battle, to deny the enemy the support of the people and to consequently make the Taliban irrelevant.

A Complex Environment: Non-Kinetic Counterinsurgency Operations

Where does reconstruction fit within the broader spectrum of counterinsurgency operations? One of the underlying themes of counterinsurgency theory is that of separating the people from the insurgent. While this may have a physical (kinetic) dimension, its primary importance is in the cognitive realm. Also known as winning the hearts and minds, the counterinsurgent seeks to provide the population with sufficient motivation to deny support to the insurgents (either physically or morally).

The contemporary environments in which land forces are undertaking counterinsurgency operations have been described as ‘complex terrain’.6 This is certainly the case in southern Afghanistan. While the physical terrain is quite challenging for the conduct of operations, it is the humans that occupy this region that comprise its complexity.

The intricacy of the human and informational dimension of Uruzgan was a constant challenge in the operations of the RTF.7 It required continuous information collection to ensure that RTF operations were based on the most up-to-date understanding of the environment. The environment changed constantly, as a result of various stimuli from coalition forces, the Taliban, local people and other actors. Ensuring that the RTF maintained and enhanced its effectiveness in the environment required an adaptive approach. Building this approach required detailed pre-deployment activity.

Winning The Adapatation Battle - Building a Foundation

The process of introducing an adaptive approach commenced prior to the deployment. There was a realisation among several key staff very early in the planning for the deployment that the task force would be conducting operations in a very complex environment. It was an environment that was largely not understood, despite the plethora of briefings and reading done by nearly all members of the task force. A detailed appreciation of the situation would require time spent in that environment. This reinforced the need to be a learning organisation, with the ability to quickly gain situational awareness and adapt operations as the understanding of the environment improved after deployment.

Given this dilemma, complex adaptive systems theory appeared to offer important insights into how the unit might be able to better understand and influence its environment upon deployment. Using a framework of complex adaptive systems for task force operations also seemed to offer the chance to improve the task force’s chances of successfully conducting operations in the medium to longer term. Consequently, complex adaptive systems theory was adopted as a supporting structure for innovation and adaptation from the formation of the new unit.

As the first task force of its type, there was significant latitude from the chain of command in how the unit would operate. No-one really knew what a reconstruction task force was supposed to look like or how it would conduct its operations. Therefore, there was significant freedom of action in how the unit’s standard operating procedures were developed. This autonomy permitted the use of complex adaptive systems theory to shape how the unit initially did business, and how it might learn from its initial experiences to constantly adapt and improve its performance.

Several principles were used in implementing an adaptive approach. First, it was based on extensive study of military history (in particular the history of military innovation). Military history is an excellent source of what has, and has not, worked over a couple of thousand years of human conflict. Given the enduring nature of warfare, a sound foundation in the history of human conflict is essential to an effective implementation of an adaptive approach. Second, whatever was adopted had to be simple. This dedication to simplicity included the use of existing terminology where possible. This was to ensure that it was understood and implemented widely, and was also transferable to subsequent task forces when they rotated into Afghanistan. This would ensure longevity of the approach.

Third, it required advocacy from the top. This is a key lesson from any study of the history of military innovation and change—commander advocacy is critical. Leaders—and initially this was a very small group but gradually expanded—had to constantly push and mould the implementation of an adaptive approach. It would have been very easy to fall back into the standard methods of operating. It took constant reinforcement and allocation of resources to the implementation of an adaptive approach to ensure it took hold.

Solid research and preparation identified previous COIN operations and the lessons therein. These formed the basis of the way the RTF would do business. Over time in-theatre, these lessons were revised continuously and can be called ‘learnt’ because the RTF adapted as circumstances changed. The RTF embodied the utility of being an adaptive and learning organisation and the military benefits of doing so.

As John Nagl states in his most recent book Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, ‘individual learning is not sufficient for an organisation to change its practices, a more complicated process involving the institutional memory is involved’.8 Prior to deployment, the unit consulted with the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) on methods of implementing a systemic approach to adaptation in the unit. Building upon individual adaptation processes, this ensured the entire organisation benefited from lessons learnt during the conduct of operations, and that these were absorbed effectively. Where possible, the unit sought to institute systems with longevity—and the simpler the system, the longer its likely endurance.

After-action reviews (AARs) were introduced from the first days of assembling the new task force. These were an important element of pre-deployment preparation and were conducted to measure whether training objectives had been met, and to assess whether task force tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) were appropriate to the likely tasks that the RTF would undertake. These AARs were also used by observers from outside the unit during the Mission Rehearsal Exercise (MRE). Facilitated by the Combat Training Centre, observers were employed to assess the performance of the new unit prior to deployment, and to make observations on the need for changes in organisation and procedures.

The principle of the task force having to ‘win the adaptation battle’ was reinforced constantly. It was also included as an explicit section of the unit concept of operations. This was necessary to ensure that the unit deployed with the organisation and procedures most appropriate to the environment in southern Afghanistan.

It was also vital in ensuring that the unit built and reinforced an ethos that allowed members of the task force to identify weaknesses—or undesirable patterns—and change them before the enemy in Afghanistan could exploit them.

The organisation of the RTF constantly evolved prior to deployment. Originally envisaged as a 200-person organisation, it deployed as a significantly larger task force. A robust security element was added just prior to deployment, although this organisation deployed later than the remainder of the unit. This resulted in a more flexible organisation, containing its own integral intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, engineering, security and logistics functions. It also provided very good freedom of action for the task force.

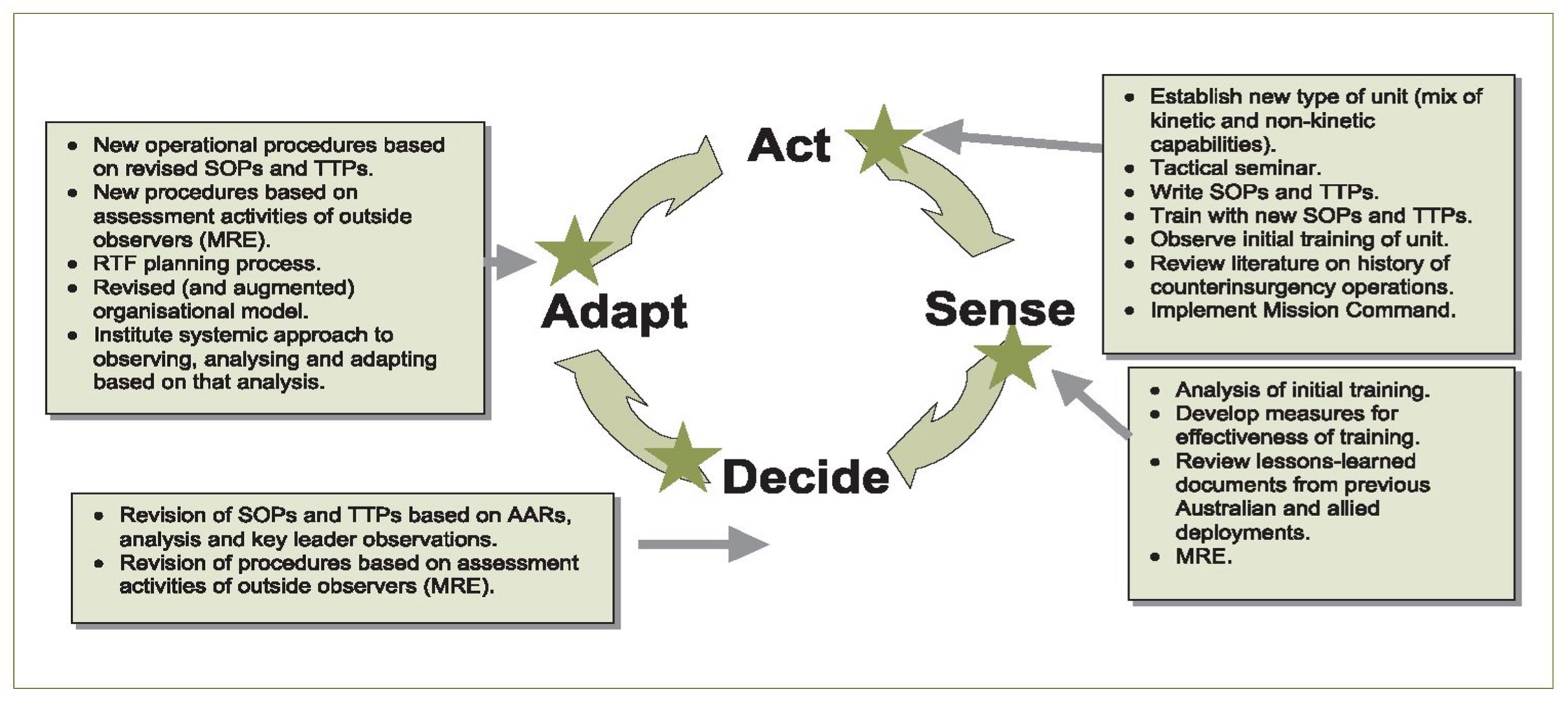

The period prior to deployment in which the reconstruction task force was raised and trained was critical to introducing an adaptive approach. While Adaptive Campaigning9 had yet to be written or released during this period, the pre-deployment activities of the RTF did fit within the Adaptive Cycle10, as shown in Figure 1.

When new ways of doing things are implemented they are, if possible, tried—rehearsed—before deployments to ensure that the organisation is familiar with new processes or equipment, and any weaknesses are identified and remedied. Implementing an adaptive approach for the conduct of reconstruction task force operations demanded a similar approach.

Figure 1. Adaptation in the Pre-Deployment Phase.

The period in which the RTF developed the tactics, techniques and procedures required for operating in southern Afghanistan was hugely challenging and often quite frustrating for many personnel. There was much trial and error while the unit undertook pre-deployment training in Australia. Much was learned about the potential for the unit to contribute to counterinsurgency operations in this time. However, it was the first months while the unit was deployed in Uruzgan that really provided the environment for exploring exactly what the task force was capable of.

Constant Adaptation - Adaptive Reconstruction Operations

On deployment, the RTF continued to focus significant energy on winning the adaptation battle. The RTF sought to be adaptable throughout the execution of its operations in the Tarin Kowt basin. This was the result of a constantly evolving security situation in Uruzgan, but also a result of the personnel of the RTF learning more each day about the strengths and weaknesses of the organisation that they had designed and deployed. An effective RTF needed to be a learning organisation. This philosophy had to be fostered by leadership at all levels.

The adversary confronting the RTF demonstrated an ability to observe coalition forces and adapt accordingly. They constantly exchanged information about any observed coalition vulnerabilities amongst themselves, including with other insurgents in distant areas. RTF operations sought to deny recognition of patterns, and limit the adversary’s ability to understand the RTF and subsequently adapt to combat it. In many respects, the unique organisation of the RTF—combining security and construction capacity in a single unit—may have posed more dilemmas for the adversary than otherwise would have been the case for a traditional unit.

Because of the unique organisation and mission of the RTF, there was no existing planning process that allowed for an integrated approach to RTF planning. The RTF adapted extant military planning processes, which were developed for conventional operations, to develop a hybrid planning process that combined the existing Military Appreciation Process (MAP), the Project Management System (PMS)11, information operations planning and healthy doses of professional military experience and common sense. It allowed RTF assets to reconnoitre, design, project manage, and conduct engineer operations within a security umbrella provided by the RTF intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and security assets.

The task force also developed simple measures of effectiveness (MOE) to ascertain progress, or lack of, in adapting to the environment. These MOE utilised both quantitative and qualitative measures to give the task force an indication of its success in influencing the environment, and a sense of where it was on the road to specified goals. It also assisted in reviewing whether those goals where still relevant in the changing environment.

Finally, a key adaptation that took place was a shift from pure physical reconstruction as the main effort, to a far greater emphasis on capacity-building. Though this often had a physical dimension, such as the construction of a trade training school or a school for healthcare professionals, the training of the local people gradually assumed a significantly enhanced role in our operations as we gained a better appreciation for the environment and for the effect that this increased investment in capacity-building would have.

The idea of the RTF needing to win the adaptation battle was constantly reinforced at all levels. This was vital in ensuring that the unit possessed an ethos that allowed everyone to notice patterns and change them, especially ineffective or detrimental ones. This systemic and formal approach to adaptation—reinforcing the informal approach that is more prevalent in military units—was an important part of the RTF’s operational philosophy.

The Next Step: Counter-Adaptation

It is logical to assume that if a friendly military unit seeks to adapt to be more suitable for the environment in which it operates, the enemy is doing the same thing. The adversary in Afghanistan had previously demonstrated the ability to adapt. As a consequence, the RTF conducted what could be described as a counter-adaptation battle against the enemy.

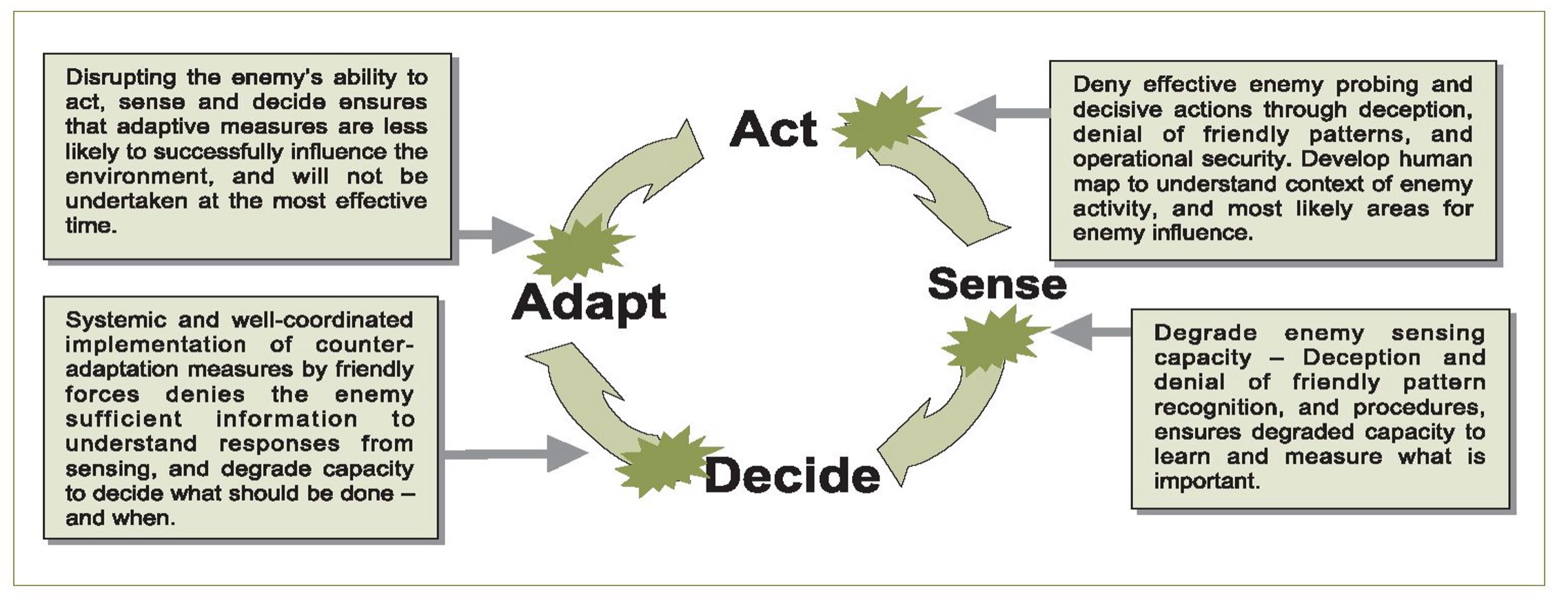

Counter-adaptation is the logical extension of the military counter-reconnaissance battle (or probing and sensing in the terminology of Adaptive Campaigning), which seeks to deny information to the enemy of friendly strengths, dispositions and intentions. Counter-adaptation operations aim to enhance friendly capacity to adapt and influence the environment while denying the adversary this same capacity.

Counter-adaptation operations seek to interrupt an adversary’s adaptive mechanisms. Using the lexicon of Adaptive Campaigning, it would influence and interrupt the Adaptation Cycle12 of those who seek to prevent friendly influence. This four-step loop is a good framework upon which to base counter-adaptation operations. This is because it is a natural approach to adaptation that any adaptive element would need to possess to be able to survive and influence others within a complex adaptive system.

The essence of counter-adaptation operations comprises four elements. First, influence the probing actions of the adversary based on the friendly understanding of the environment. Second, degrade the adversary’s sensing capacity by denying the recognition of any friendly patterns and procedures. Third, recognise adversary patterns and exploit them to friendly ends. Finally, deceive the enemy to ensure that any adaptations the adversary makes are low-quality adaptations (disrupting the decision process and the overall adaptation cycle).

The identification of patterns is a key method that both human and non-human predators employ to attack their prey. Just as friendly forces will seek to identify patterns that can be exploited in the behaviour of an adversary, so too the capacity of the enemy must be limited in seeking to do the same against friendly forces. The task force went to great lengths—and consumed considerable energy to include this in its planning process—to ensure that everything possible was done to not set patterns that the adversary could exploit.

Despite this, it would be naïve to think that friendly forces will always be able to avoid setting patterns. Therefore, it is vital to ensure the adversary is denied recognition of any patterns. The key to this is friendly forces recognising first their own patterns and making changes before the adversary identifies and exploits them. Once again, through the use of detailed afteraction reviews for every mission, and the analysis of those reviews by intelligence and operations staff (as well as senior staff), this approach was incorporated into RTF operations.

Friendly forces must recognise adversary patterns and exploit them. For military reconstruction operations, this means ensuring the enemy has limited capacity to have a negative impact on our reconstruction activities. While this may at times require kinetic operations, these will only have short-term, tactical effects. Exploiting adversary patterns and using them to generate non-kinetic effects within the population of the disrupted society has a more enduring legacy and helps make the adversary irrelevant to the population.

It is important to be active in influencing an adversary so that any adaptations they attempt are low quality. This can be done through deceiving the enemy about the true capabilities of various friendly systems so that enemy adaptation is based on wrong estimates of capabilities. Additionally, ensuring that friendly counteradaptation measures are closely orchestrated and integrated into the planning of all operations from their conception will ensure that friendly forces have a better chance at negating the adversary’s influence in a given environment.

Key to the conduct of counter-adaptation operations will be the continuous collection, fusion, analysis and dissemination of information on the environment. The aim should not be to seek a perfect overall picture, but to gain enough information to make decisions of good quality faster than the adversary. This reinforces the need for intelligence-led reconstruction.

Future Implementation

There is still much to be done in implementing an adaptive approach in a systemic manner. The implementation in operations of the adaptive stance will require some trial and error to ensure that the most effective manner of employment is adopted. However, based on the experiences of 1RTF, several issues are apparent.

Figure 2. The Adaptation Cycle and Counter-Adaptation.

First and most importantly, keep it simple. The environment in which contemporary operations take place are enormously complex. The technical and human resources employed are also very complex organisations. Therefore, in aiming to give friendly forces a better chance of success through adaptive operations, operational planning and execution should not be complicated through introduction of this approach. Any adaptive approach must be easily understood by key leaders and staff, and they in turn must be able to translate the complex ideas and terminology associated with the study of complex adaptive systems into a lexicon that is understood and employable by those they command. The ACT - SENSE - DECIDE - ADAPT loop, described in Adaptive Campaigning, provides a simple yet effective approach to how units can better understand and influence their environment. It is a simple model that does not seek operational perfection, but instead seeks to ensure friendly forces are more successful in their environment relative to any adversary.

A simple approach also demands simple yet effective mechanisms for measuring success, to provide valuable feedback for the conduct of subsequent operations. The 1st RTF developed a simple yet effective set of measures linked to its objectives, which provided feedback on short and longer term adaptations required within the unit, as well as for other adjoining units and follow-on RTFs. This type of approach needs to continue to be developed.

Any approach to simplifying the adaptive approach must consider terminology. The military will, and indeed should, resist the introduction of any fancy new lexicon associated with complex adaptive systems. Where existing words, phrases and terminology can be employed to describe the adaptive approach, they should be. This will aid in institutional acceptance.

Second, this is not something that can quickly be developed during operations—inculcating an adaptive approach in a military unit needs to start long before any deployment. As the history of military innovation shows, significant innovation—or adaptation—needs to have some time to develop before the conduct of operations. While in the contemporary environment we may not have the luxury of the Interwar Period of 1918-1939 to develop new forms of doing business, we do need some time ‘out of contact’ for innovation to take place. It must be part of the culture of a unit, and there must be ‘buy in’ by commanders and their subordinates. This includes a robust adoption of mission command and the capacity to undertake effective self-critiques of unit performance.

Next, implementing an adaptive approach must be led from the top. Unit commanders and their subordinate leaders must understand, and support, the implementation of the various mechanisms to support better quality adaptation in military units. This advocacy from the top is critical. In 1983 US Army General Donn Starry, writing about change in military organisation, stated that:

someone at or near the top of the institution must be willing to hear out arguments for change, agree to the need, embrace the new operational concepts and become at least a supporter, if not a champion, of the cause for change.13

In a unit this will normally be the commanding officer. However, this advocacy will be required at various echelons above unit level, all the way to the top of the organisation. This will be a difficult undertaking for an organisation such as Army. It is certainly possible, but it will require senior leaders to understand, embrace and sell the adoption of this approach if it is to be successfully embraced by the wider organisation.

Not only must senior leaders convince their subordinates of the effectiveness of this approach, they must also ensure that other organisations with which Defence works, such as the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and aid organisations, appreciates the adaptive nature of military organisations and how they intend to operate. Publishing a concept such as Adaptive Campaigning is a start, but much more will need to be done. In addition to Australian Government institutions, a common approach must be forged with Australia’s principal allies and coalition partners. This will ensure that the cultural, as well as technical, framework that Australian Defence Force elements work within during coalition operations is familiar and is exploited by the coalition force as whole.

The senior leaders that advocate the adaptive approach must also foster continued examination of the benefits of exploring complex adaptive systems. In an organisation as busy as Army, we often need a separate organisation to undertake some of the theoretical development of alternative ways of conducting operations. The relationship between scientific organisations such as DSTO and soldiers is critical. Both play important roles in implementing an adaptive approach, as well as working to identify additional areas that can be exploited to enhance the effectiveness of military organisations. Ensuring there is an effective link to facilitate an effective transfer of theory into practice is a key part of this. The intellectual underpinnings provided by organisations such as DSTO will be a key enabler.

Fourth, advocates for the adaptive approach must ensure that systems implemented for adaptivity have longevity. It is a waste of valuable time and resources to implement an adaptive system that only endures as long as its original promoter remains in the unit. The advocate must ensure other key leaders ‘buy into’ the changes and ensure its continuation after that advocate departs the unit. Obviously in military operations there are lots of ways an advocate for these kinds of changes may leave the scene. Therefore, the value of the adaptive approach should be apparent to others—and the implementation systemic enough—to ensure they survive the departure of that advocate. This continuity of approach is vital.

Finally, it is not enough to implement systems that ensure that friendly military organisations are adaptive. It is just as vital that friendly forces interfere with the adaptive capacities of those that seek to hinder our capacity to achieve our objectives. There must be an aggressive approach to degrading the fitness of opposing forces. There are actions in both the kinetic and non-kinetic realms that we and our coalition partners, civilian and military, are able to take that can hinder the capacity of our adversaries to effectively adapt. The conduct of counter-adaptation operations against adversaries must be part of any adaptive approach that is set in motion in military organisations.

To inculcate military organisations with an ethos that encourages a greater level of innovation takes time. It will take both time and effort for more leaders to come to understand and appreciate the potential benefits of an adaptive approach based on a comprehension of complex adaptive systems. While some individual units may develop their own techniques, ensuring a consistent method across Army and the other Services will require a significant education campaign—and investment in the various training and education mechanisms— from the top to the bottom of the organisation. Ensuring a military unit is able to undertake effective adaptation takes an investment in both human and financial resources. However, the return on this investment is likely to be significant.

Conclusion

With so many successful insurgencies ... the temptation will always be great for a discontented group, anywhere, to start the operations. Above all, they may gamble on the effectiveness of an insurgency-warfare doctrine so easy to grasp, so widely disseminated today that almost anybody can enter the business.14

The aim of this paper has been to explore one practitioner’s view of implementing an adaptive approach in military operations. Just as Krulak’s ‘three-block war’15 brings to mind a multitude of different types of joint and interagency operations, the term ‘winning the adaptation battle’ seeks to encapsulate an entire concept—a way of doing business. What the reconstruction task force undertook, seeking to be a more adaptive organisation, represents the initial steps. But even this posed significant challenges before, and during, the conduct of RTF operations.

Counterinsurgency operations are very complex undertakings. They require the commitment of a range of national resources, only one of which is the military. They present military organisations with particular challenges. The historical strength of an army, the coordinated and disciplined destruction of an enemy force, can at best only have a tactical effect in a counterinsurgency campaign.

Given the low entry threshold of insurgencies, counterinsurgency operations are likely to absorb the attention, and resources, of Western military organisations for some time to come. The junior officers that are graduating from their basic training today could be conducting these types of operations for their entire careers. Consequently, military organisations must be able to adapt themselves, from top to bottom, to be able to remain an effective and relevant option for governments in countering the likely range of insurgencies in the coming decades.

In her paper The Implications of Complex Adaptive Systems Theory for C2, Dr Anne-Marie Grisogono has identified that learning from experience to produce more effective future performance is a defining characteristic of complex adaptive systems.16 By adopting a systemic approach to learning from experience and using those lessons to adapt and better influence its environment, the experiences of the 1RTF provide important lessons for the implementation of the adaptive approach in military units.

Endnotes

1 Anne-Marie Grisogono and Alex Ryan, ‘Adapting C2 to the 21st Century: Operationalising Adaptive Campaigning’, Paper presented to 12th International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, June 2007, Newport, USA.

2 F Hoffman, ‘Neo-Classical Insurgency?’, Parameters, Vol. XXXVII, No. 2, Summer 2007, p. 71-87.

3 Major al-Qaeda, Taliban, Haqqani Network (HQN), and Hezb-e Islami Gulbiddein (HiG) sanctuaries exist in Waziristan in eastern Pakistan; see AH Cordesman, ‘Winning in Afghanistan: Challenges and Response’ Testimony to the US Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, February 2007.

4 It must be acknowledged that the influence of DSTO research into adaptation and complexity in Defence was significant in implementing the RTF’s approach to adaptation. The theoretical work completed in the last few years by DSTO provided a good foundation for the subsequent introduction of systems to facilitate an adaptive approach for RTF operations.

5 This requires the adaptive approach to be accepted by the majority of personnel, and all key leaders, in a unit as the preferred approach to the conduct of operations and the means to constantly increase chances of success and better influence the environment in which that military unit finds itself.

6 Lieutenant Colonel D Kilcullen, Future Land Operating Concept: Complex Warfighting, Army Headquaters, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2004, p. 5.

7 For a more detailed view of this environment, see M Ryan, ‘The Other Side of the COIN: Reconstruction Operations in Southern Afghanistan’, Australian Army Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, Winter 2007, pp. 124-43.

8 J Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005, pp. 6-7.

9 Commonweath of Australia, Adaptive Campaigning, Army Headquarters, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2006.

10 Ibid, p. 7.

11 The PMS is a technical engineer project management process developed by the Australian Army’s 19th Chief Engineer Works.

12 Commonweath of Australia, Adaptive Campaigning, p. 7.

13 D Starry, ‘To Change an Army’, Military Review, March 1983, p. 23.

14 D Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, Frederick A Praeger, New York, 1964, p. 143.

15 The term ‘three-block war’ was first used by United States Marine Corps Commandant, General Charles Krulak, in an article for Marines Corps Gazette entitled ‘The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War’ in 1999.

16 Anne-Marie Grisogono, ‘The implications of Complex Adaptive Systems Theory for C2, Paper presented to the 2006 Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, p. 5.