Abstract

This article reflects on the operation of the Australian Army’s 1st Reconstruction Task Force, which deployed to Afghanistan’s Uruzgan Province in August 2006. The author highlights the importance of civil affairs, such as reconstruction, education and capacity-building, in an overall counterinsurgency effort.

As for the character of our enemies, they have been unusually ruthless and nihilistic. Their only purpose in violence has been to tear down, not to build up an alternative vision they genuinely support. They are ruthless killers who often seem to kill just for the pleasure of it. There is no merit in [their] vision according to any serious cultural or moral code in the world today.

- Michael O’Hanlon 1

Introduction

Since Western nations commenced operations in Afghanistan in 2001, they have undertaken a complex counterinsurgency. As General David Petraeus commented recently, the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan were not the wars for which the armies of the West were best prepared.2 Yet these are the wars in which many Western armies are engaged—and are likely to be so for the foreseeable future. Insurgency will be the favoured approach of violent non-state actors well into the twenty-first century. Ironically, the nature of Western armies is at least part of the problem: the overwhelming superiority of Western military forces now compels those who wish to challenge the status quo to resort to insurgency operations. Such operations claim many recent successes in Iraq, the southern Philippines and Afghanistan.

Faced with the complex challenges of counterinsurgency operations in southern Afghanistan, and the need for cognitive-realm solutions to counter the extreme ideas of the Taliban, the Australian Army has fashioned its own response in the development of the reconstruction task force organisation. The first of these organisations, the 1st Reconstruction Task Force (RTF), deployed to Afghanistan in August 2006 as part of the Dutch-Australian Task Force Uruzgan. For eight months, this task force worked to rebuild the physical infrastructure of Uruzgan Province, to build an indigenous capacity to undertake engineering activities there and to support the Dutch Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT).

This article examines the role and contribution of Australian Army reconstruction operations as an element of the counterinsurgency fight in southern Afghanistan. The overarching purpose in Uruzgan was to make the Taliban irrelevant. With this aim in mind, this article examines the way in which the 1st RTF conducted its operations and projects a future path for civil affairs activities.

COIN and Reconstruction

Reconstruction and civil affairs are not obvious elements of counterinsurgency operations, a term that, to general understanding, simply suggests the prosecution of insurgents. Yet reconstruction does have a place within the broader spectrum of such deployments. One of the mainstays of counterinsurgency theory is the separation of the insurgent from the populace. While this theory certainly has a physical and ‘kinetic’ dimension, counterinsurgency rests primarily in the cognitive realm—commonly known as the ‘battle to win the hearts and minds’. The counterinsurgent must persuade the population to withdraw physical and moral support for the insurgent.3

Like other counterinsurgency campaigns, the outcome of the war in Afghanistan will be decided by the degree to which the counterinsurgent gains the support of the people. This demands a continuous balancing act between kinetic actions (the employment of lethal force undertaken by the combat arms) and non-kinetic actions (undertaken by Provincial Reconstruction Teams and the Reconstruction Task Force). The RTF trod a difficult path between the kinetic and non-kinetic elements of the military contribution to counterinsurgency operations, seeking to present the Afghan population with a softer side to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).4 Coalition forces were portrayed not as a destructive presence, but as a force for good, focussed on rebuilding and assisting local communities.

Military reconstruction operations provide time and space for the creation of indigenous capacity to backfill military capabilities. They also allow time for the eventual arrival of aid organisations. In many areas such as southern Afghanistan, the tenuous security situation prevents a vast majority of aid groups and other agencies from establishing a presence. However, there remains a dire need for nation-building and reconstruction in addition to security operations. This must be provided by highly capable organisations with the integral mobility and protection to allow the conduct of reconstruction with minimal physical interference from the insurgent. Only military organisations—and military engineers in particular—possess the ability to undertake reconstruction activities while concurrently providing a robust level of self-protection. It is the military reconstruction operation that provides the critical link between warfighting operations and the return of normality to civil society.

The conduct of reconstruction operations by military engineers and attached elements of the combined-arms team requires the diversion of a significant level of resourcing from traditional security operations to areas previously considered support roles such as construction and civil liaison. Yet the benefits of reconstruction are not confined to restored infrastructure. Military engineers have the ability to transfer skills in basic trades and the planning and conduct of construction tasks to the local populace to ensure the growth of indigenous capacity. Providing skills to the population is an effective way to assist Afghans to help themselves, and is also an important element of ISAF’s ultimate exit strategy.

A Complex Environment

Undeniably, the human dimension was the most complex aspect of the environment in which the 1st RTF operated. While the physical environment in Afghanistan was extremely demanding, it was the people of the province who determined the complexity of the environment as a whole. Ethnically, the inhabitants of Uruzgan are overwhelmingly Pashtun. Tribal affiliation provides the single greatest distinction within the local people and, during the 1st RTF tour in Uruzgan, the Populzai was the dominant tribe in the region, boasting the Governor and senior security personnel among its members. Populzai dominance—and the enmity it sparked— remained a constant sensitivity.

Inter-tribal rivalry, however, was not the only source of tension. The drug trade plays a key role; Uruzgan is one of Afghanistan’s largest producers of poppies. This illicit industry constitutes the most significant proportion of the local economy and involves a large percentage of farmers and other members of the community. As a consequence, any effort to disrupt the drug trade incurs hostility from the local people and active and violent resistance from drug traffickers and major dealers.

Other sources of conflict in the province include political differences, residual conflict over the roles of various individuals during the Soviet occupation, and honour killings under the Pashtunwali code of conduct that governs behaviour throughout most of Uruzgan.5 The parlous nature of provincial governance provides a further level of complexity.

A further complicating factor in this intricate and difficult environment is the presence of the Taliban. While not as active in Uruzgan as in some other parts of southern Afghanistan, the operations of the Taliban applied constant pressure throughout much of the RTF’s deployment. The effect was a constant requirement for security on worksites, during convoys and on engineer reconnaissance. Taliban tactics were principally indirect, and they favoured the use of improvised explosive devices and rocket attacks to disrupt Coalition operations.

This complex tableau of ethnic and tribal affiliations, political allegiances and government agencies, local and foreign adversary forces, criminal/drug groups and Coalition forces presented the RTF with constant and multifaceted challenges. Sources of conflict were never clear-cut: it was rarely a simple matter of Taliban versus Coalition forces. Likewise, the linkages between different actors, some of whom the RTF was required to interact with regularly, were far from apparent.

Physically, the area in which the RTF conducted operations was notable for the striking disparity between the ‘green zones’ along the rivers and the harsh and arid desert that dominated the remainder of the province. The green zones represented a significant physical obstacle—a complicated amalgam of irrigation channels, orchards, small villages and wadis that contained the major concentrations of people and also provided perfect concealment for the insurgent. The basin in which the RTF primarily worked was surrounded by high mountains: rocky, sheer and totally devoid of vegetation.

The climate served to exacerbate the daunting physical challenges. From May through to November, the weather is searingly hot and dry, with dust storms a constant hazard. The beginning of the year, however, saw the arrival of rains that, while dampening the dust, bedevilled operations by clogging the transport of goods into the area. The onset of winter brought extreme cold weather (down to minus 15 degrees Centigrade) and confirmed perceptions that this was a harsh and hostile climate in which to work.

The complex situation—both physical and human—in Uruzgan constantly tested friendly operations. Coming to terms with this intricate environment was crucial from the earliest stages of planning for the deployment. This was a mission that would require an intelligence-led organisation.

Intelligence-led Reconstruction

One of the basic tenets of reconstruction operations is that they must be intelligence-led—knowledge of the operational environment is paramount. Within the human environment, understanding the complex interrelationship between family, tribal and political loyalties was a significant undertaking. Even in a small province such as Uruzgan, simply forming some appreciation of the scope of the problem took many months.

From the onset of pre-deployment preparations and throughout the actual conduct of these operations, the development and updating of a ‘human map’ of the province was the highest intelligence priority. This ‘map’ provided a view of the key people in the province, their relationships and interactions. Possessing this ‘human map’, continually updated using complex adaptive systems theory, equipped the commanders and staff with insights into the dynamics of the province and the ability to assess the impact of RTF projects on the various local actors.

Human intelligence operations are the force multiplier for these types of missions. Human intelligence had to be employed effectively to enable the RTF to undertake the right project at the right place and time and to ensure robust force protection measures. The RTF’s most important human intelligence asset comprised the eyes and ears of its members, who interacted constantly with local people in villages, on worksites in the provincial capital Tarin Kowt, at the Trade Training School and in meetings. This interaction provided invaluable opportunities to gain insights into the local situation and, importantly, also to convey messages from ISAF and the Government of Afghanistan.

The fusion of all of the information collected was a major undertaking and allowed the RTF to overlay all its sources and build an informed picture of the area. This fused product shaped operations by providing insights into the needs of the local population and the intentions of the Taliban and other adversary elements in the province.

Intelligence-led reconstruction was the most effective method of conducting an operation of this nature. Above all, it ensured that all projects were conducted where and when they were needed. It ensured that deployments to small villages supported the right people and were aimed directly at stealing support from the Taliban. Intelligence was gleaned from the lowest levels, but also disseminated through the chain of command. Ultimately, if the conduct of counterinsurgency operations—and reconstruction operations—relies on strategic corporals and privates, then those corporals and privates must have access to accurate and timely intelligence on which to base their decisions.

A Conceptual Model for RTF Operations

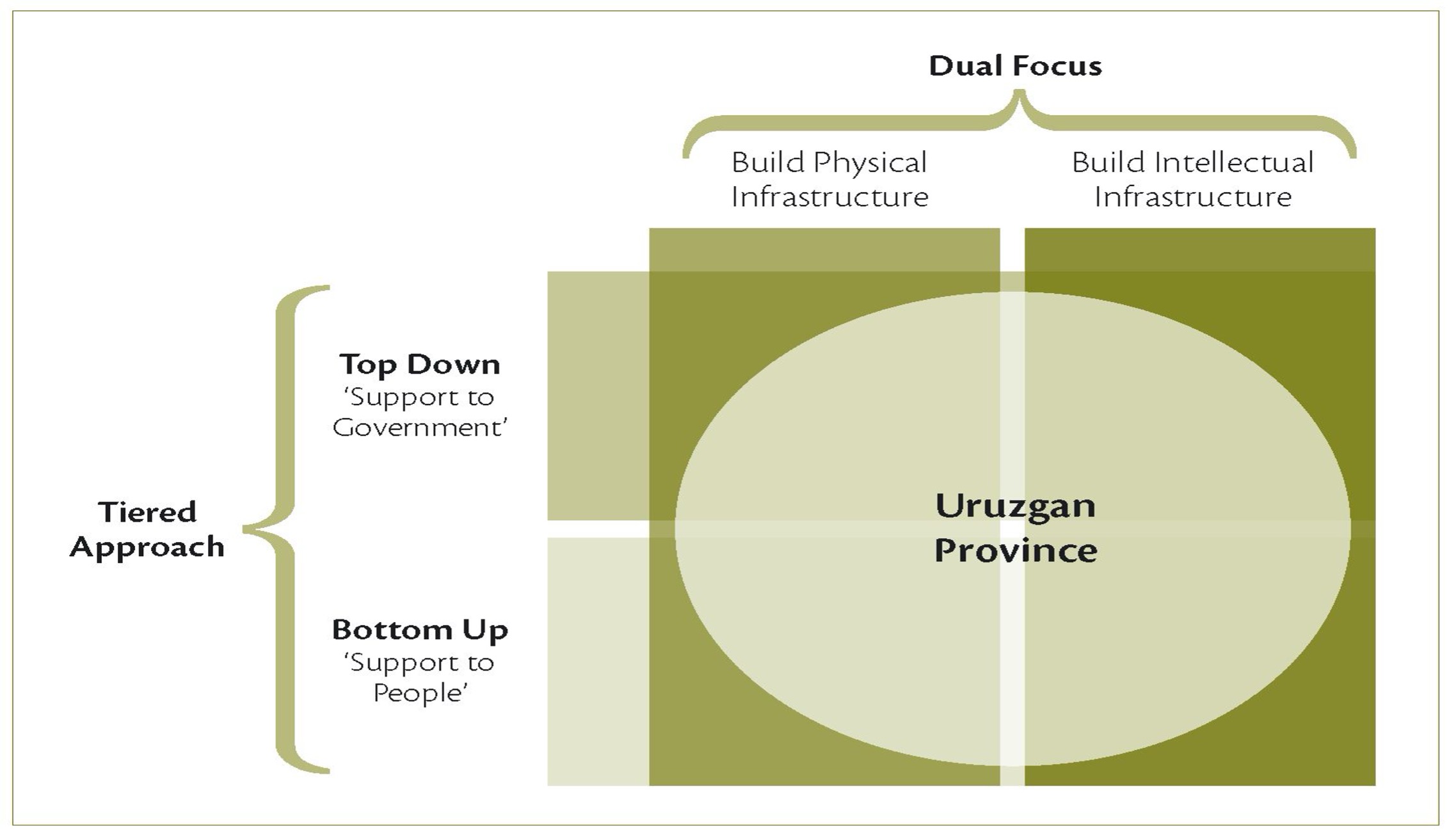

As its concept of operations unfolded, it became apparent that the RTF required a concept of what to achieve. The RTF conduct of operations evolved into a very simple conceptual model. This model had two separate but mutually supporting binary approaches, and overlaid them in a single concept. The first of these binary approaches was the two-tiered, top down, bottom up approach. This meant that the RTF conducted concurrent operations to rebuild government institutions and infrastructure (top down) based on the priorities of provincial officials, as well as conducting small-scale missions to assist the people in individual villages (bottom up) based on their community priorities.

The second part of this conceptual model involved sustaining a dual focus of physical and intellectual (capacity-building) reconstruction.6 As impressive as new hospitals, clinics, schools, bridges and other infrastructure may be, it is the capacity of local people to staff this infrastructure and maintain it in the long term that is of overwhelming importance. Consequently, the RTF also conducted extensive trade training and developed an education infrastructure.7 This ensured that reconstruction projects not only had an immediate effect, but that the capacity-building element incorporated into each project ensured its longevity through the training of local men in maintenance and the development of project management skills in provincial government officials.

Provincial Infrastructure Development and Rapid Reconstruction

Consultation with local officials and other interested parties was a critical aspect in prioritising the RTF’s construction projects. A weekly engineer forum for all provincial and Coalition engineer organisations was established early in the deployment to separate the various engineer projects and provide a forum for professional debate. This was supplemented by regular meetings with provincial officials to discuss the details of individual projects and ensure that what was needed would be matched by what was delivered.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of RTF operations

The 1st RTF deployed with a strong planning capability that integrated engineer, security, intelligence and information operations (IO) planning in a single entity. From within the Task Force Headquarters, the plans section reached out to the PRT and provincial officials to prioritise works that accorded with provincial and ISAF developmental requirements. These priorities were then used to develop a monthly works plan that determined the location of projects and RTF deployments, as well as dictating budget planning.

The capability provided by the works section was integral to this. Embedded within the S3 (Operations) cell, this small yet highly capable element provided civil engineers, works supervisors, drafting and surveying capacity. As components of the operations section, security and information operations planning were incorporated into engineer planning for projects from their inception, providing significant flexibility in the execution of reconstruction tasks. The works section was able to design and manage projects for both integral engineer elements and contractors. Further, the works section was able to use its ability to confer with other Army engineer units in Australia to secure additional advice on technical engineer issues.

This hybrid planning process also allowed greater flexibility in project execution. Integral assets from the RTF engineer squadron could be employed, as could local contractors. At times, the nature of the project—such as the renovation of the provincial hospital—required a mix of both. This meant that the RTF was effectively able to undertake top down projects and bottom up projects concurrently. Top down projects saw the plans section conducting reconnaissance, design and the project or contract management required to oversee civilian contractors on these lengthy, large-scale tasks. Bottom up projects initially involved the plans section; however, execution occurred via a task-organised combat team with an engineer organisation tailored to each task. These bottom up tasks were conducted in small villages in the vicinity of Tarin Kowt and, consequently, a blend of security and engineering was required for each, supplied by the integral engineer squadron and security company of the RTF. Generally, each of these tasks comprised a specific operation on which the PRT also deployed one of its mission teams for local liaison.

In one initiative, the RTF developed tailored village packages—literally ‘one-stop shops’ for village reconstruction projects. Traditionally, engineers conduct reconnaissance, retire to prepare for the task and then redeploy to complete the work. It became clear very early in the deployment that, while efficient, this would not be effective due to a potential loss of credibility with the local people. Instead, taking village ‘packages’, consisting of pre-fabricated mosque renovation kits and water storage tanks or tank stands, were taken on the mission. These rapid reconstruction tasks (colloquially known among the troops as ‘backyard blitzes’8) constituted, quite literally, an adaptation driven by local requirements. Identifying credibility as a cornerstone, the RTF developed its operations around these rapid reconstruction tasks that would commence as soon as consultation with village maliks was completed.9 While the scope of these ‘backyard blitz’ tasks was small, the return in good will and improvement in the lives of those assisted was considerable.

The immediacy of this action had an enormous impact on local villagers. Coalition forces were seen to be delivering on their promises, lending ISAF operations significant credibility. The lives of the local people were also immediately and substantially improved and the mosque renovation kits sent the additional message that the Coalition forces respected Islam. This had instant information operations benefits as it clearly countered Taliban propaganda to the contrary. In a tribal society such as Afghanistan, winning over the villagers is critical. These villages constitute the key terrain in such a counterinsurgency campaign, and must be won over—one at a time if necessary.10

These rapid reconstruction tasks were underpinned by a significant intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) effort that included engineer reconnaissance from previous operations. Given the nature of these operations, the construction element of the activity was initially planned and the enabling security concept then ‘wrapped’ around the construction. Flexibility and adaptability were key concepts in the conduct of RTF operations.

The RTF also enjoyed significant flexibility through the availability of adequate funding at short notice. A large budget for reconstruction projects was approved prior to deployment, with key personnel given the appropriate delegations to approve the expenditure. Works section staff were also trained in complex procurement methodologies. A financial advisor was included in the headquarters, ensuring rapid feedback on the availability of funds prior to the approval of expenditure. The combination of this allocation of money with appropriate delegations and complex procurement skills ensured that the RTF had the flexibility to expend large amounts of money on major projects without constant reference to Australia.

Building Capacity

Capacity-building is a consistent theme in the approach of various government and non-government organisations to nation-building operations. While the organisation of the 1st RTF incorporated a trade training capacity from its inception, this area was notably under-appreciated prior to deployment. The first trade training courses—each of one month’s duration—were very successful both in increasing the basic skills of the local youth and in striking a blow in the information operations campaign. News of the RTF Trade Training School spread rapidly by word of mouth, and RTF personnel on operations around Tarin Kowt were constantly asked by local people to include their young men in the courses. Eventually the curriculum was also expanded to include a small engine maintenance course. As an additional incentive for young men to apply for these courses, a training wage was paid to all trainees. At the end of the course, graduates received formal qualifications in their trade (in Pashtu) and a tool kit. The RTF then assisted graduates to find employment, with some graduates subsequently working as trainee instructors at the Trade Training School. By the latter stages of the deployment, all courses had at least one Afghan instructor who was a graduate of the school. This was a deliberate strategy to ensure that once RTF rotations in Tarin Kowt ceased, there would be an indigenous capacity to continue vocational training in the area.

Another area of capacity-building led by the RTF involved the training of Afghan National Army engineers. While this task was not anticipated prior to deployment, an opportunity arose early in the tour to have Afghan Army engineers attached to the Task Force. The RTF adopted a ‘train and partner’ approach based on a monthly rotation in which Afghan Army engineers would receive a week of formal instruction in combat engineering, followed by two weeks of deployment on RTF operations and a week’s leave. The partnering of the Afghan engineers with their embedded US Army trainers allowed the RTF to conduct village tasks using Afghan soldiers. This not only gave the RTF greater credibility in the eyes of the villagers, but created the perception in local Afghans that their army was a credible and constructive part of society.

A further aspect of RTF capacity-building involved mentoring provincial officials. The RTF developed links with key personnel within the Ministry of Reconstruction and Rural Development, as well as with the office of the local mayor. Senior RTF personnel formed close bonds with the leadership of these two provincial entities, fostering a more informed process for prioritising RTF projects and developing trade-training capacity.

Kicking the Taliban Where It Hurts

Working with and for the local people is a key element of successful counterinsurgency operations. For the RTF, this involved meeting with local people and listening as they detailed their needs at provincial and village level. It also entailed more subtle elements that impacted on the way the RTF operated.

Building a sound knowledge of local culture took time before and during the deployment, but was critical to interacting with local people. Gaining an understanding of the human or social elements in the area of operations was a high priority throughout the RTF’s tour in Uruzgan. To achieve this, the RTF started slowly, gradually gaining a more detailed picture. The first projects did not start until the unit had been in the area for some time so as to allow the RTF sufficient time to ensure that these projects met local requirements.

RTF staff worked hard to ensure that every facet of the relationship with local people was based on respect. Every RTF member undertook substantial cultural training prior to deployment, especially in the local Pashtunwali code of conduct, so as to provide a solid foundation for dealing with the people of the Tarin Kowt area. The first standing operating procedure of the 1st RTF was the code of conduct for its soldiers. This code were issued to every soldier prior to deployment and constantly reinforced throughout. It included guidance on dealing with the various elements of Tarin Kowt (Pashtun) society, as well as local norms and practices.

This initial interaction and the delay in initiating projects also ensured that the RTF was not making promises it could not keep. Through detailed discussions with local people, the RTF carefully managed expectations and promised only what it could deliver. This was a reaction to the constant complaint by local people that government and Coalition forces would promise projects, but not deliver. From this initial interaction grew the ‘backyard blitz’ approach to village reconstruction missions described earlier. The enduring theme of RTF operations became ‘promise only what can be delivered and deliver on everything that is promised’. This was translated by RTF soldiers into the classically Australian line: ‘we don’t make promises, we just build stuff.’

The RTF also maintained a minimum level of local labour for every contract signed with local construction companies. The aim of this policy was to keep local men employed in constructive endeavours, foster the transfer of work skills and inject money into the local economy. Local companies often tended to employ labourers from outside the province. To enhance employment opportunities for local people, the RTF set a benchmark of 70 per cent local labour for each of its projects. This became a contractual obligation for contractors, some of whom were penalised for non-compliance by being locked out of the worksite. During the tendering process, any contractors who identified that the technical nature of a project would prevent them reaching this minimum level of local labour would be engaged in contract negotiations and a compromise effected.

Constant negotiation was a feature of the relationship between the RTF and local officials. Throughout the scoping and design phases of RTF projects, there was extensive consultation and negotiation with local officials. However, even when agreement was reached and contracts had been signed (and even when construction was underway), local officials would often seek to re-negotiate contracts. RTF staff listened to the concerns of these officials and endeavoured to reach a compromise that was agreeable to both sides. RTF staff quickly learned that they could not assume that changes would not be sought simply because construction had commenced. The RTF accepted that this was the ‘Afghan way’ and ensured that neither side lost face during the ongoing negotiations.

Conveying the Message

Many members of the task force augmented their cultural knowledge by learning the local language, Pashtu. Many soldiers also undertook regular refresher training while deployed. While they rarely became fluent, the local people responded very positively to soldiers who were seen to be making an effort to interact and understand local norms. The effect of Australian soldiers who were able to say ‘g’day’ in the local language was often quite pronounced, especially in the smaller, more remote villages.

Interaction between the local people and the RTF was enhanced by the use of interpreters who played an essential role in RTF operations. The interpreters, employed by the RTF, were contractors and citizens of other nations, and yet were treated as full members of the RTF. This facilitated their use in detailed technical discussions with provincial officials on complex project-related issues. Importantly, the interpreters were able to translate nuances in conversations that were crucial to gaining an overall understanding of the local people. Without these interpreters the RTF would not have been able to effectively assess local needs and requirements and then transform this into physical construction and capacity-building projects.

Every effort was made to give credit to the local people and agencies for projects undertaken by the RTF so as to lend credibility to local government institutions and to endow local people with ownership of projects. This approach also worked to minimise adversary targeting of RTF projects.11

The 1940 United States Marine Corps publication, the Small Wars Manual, noted that ‘tolerance, sympathy and kindness should be the keynote of our relationship with the mass of the population.’12 Working effectively with and for the local population was a central tenet of RTF operations. Developing a sound familiarity with local culture was crucial to this interaction and made a significant contribution to the operational capability of the task force.

An integral part of RTF operations was devoted to ensuring that information concerning infrastructure development and capacity-building was conveyed to the local population as well as to Coalition partners and the Australian people. This was achieved by employing standard doctrine, which states that: ‘The relationship between security forces and the local population must be based on mutual respect and confidence which, in turn, is based on accurate information and understanding.’13 Consequently, a strong information operations plan emphasising strategic communications was integral to every RTF activity.

Information operations were a dominant consideration from the very outset of each planning process. There were many target audiences at different levels and informing these different audiences was a time-consuming and laborious process, but an absolutely essential element of operations. Considerable effort went into ensuring consistency of RTF message to deny the adversary the ability to exploit seams in the Coalition’s public information campaigns. As the penetration of electronic media in the province was relatively limited (with the exception of radio), the principal means to convey information to the local people involved printed matter and word of mouth. Every RTF mission employed these methods to ‘tell the Coalition’s side of the story’ as a central tenet of operational practice.

Coalition forces in southern Afghanistan are locked in a constant IO battle with the adversary. The Taliban has the ‘home ground’ advantage in its ability to shape the information environment. Coalition forces use the truth to maintain their legitimacy while the Taliban frequently makes outrageous claims concerning the actions of the Coalition forces and the Afghan Government. The Taliban has a simple yet effective IO approach that seeks to separate the population from the Coalition forces by informing media and United Nations organisations of any instances (true or otherwise) of Coalition involvement in civilian casualties. They have amply demonstrated their effective understanding of how to exploit modern media (especially the Internet) as well as age-old methods such as night letters.

Constant Adaptation

The RTF focussed considerable energy and resources on winning the adaptation battle. This meant that the unit had to be a learning organisation at every level. John Kiszley recently wrote that ‘adapting to counter-insurgency presents particular challenges to militaries, and many of these challenges have at their root issues of organizational culture.’14 The need to constantly adapt was driven by the continually evolving security situation in Uruzgan, as well as the fact that RTF staff learned more each day about the strengths and weaknesses of their new organisation.

The Taliban demonstrated an ability to observe Coalition forces and adapt their own operations accordingly. They constantly exchanged information with other insurgents, some in distant areas, concerning observed vulnerabilities. RTF operations aimed to disguise patterns and limit the adversary’s ability to understand the Task Force and adapt. Put simply, the RTF conducted a counter-adaptation battle. This equates to the counter-reconnaissance battle of conventional operations and sought to enhance the RTF’s capacity to adapt to a situation while denying the adversary this same adaptation. The unique organisation of the RTF, which combined security and construction capacity in a single unit, may also have posed more dilemmas for the adversary than that of a traditional unit.

After-action reviews were key features of RTF operations and were used to assess whether objectives had been met and whether tactics, techniques and procedures were appropriate to that operation and those foreshadowed. RTF members also attended the after-action reviews of other units in Task Force Uruzgan and analysed their patrol reports to add to the information store of the RTF. The outcomes were widely disseminated and used to plan subsequent operations. The commander of each mission also briefed staff members following each operation so as to enhance their situational awareness and highlight areas for improvement in planning. At the soldier and non-commissioned officer level, weekly formal training was conducted throughout the deployment on issues related to the conduct of the mission and lessons learnt during RTF operations.

The RTF also sought to learn from the experiences of others. Prior to deployment, lessons on previous operations in Afghanistan and other counterinsurgency operations were analysed and discussed within the Task Force. These lessons were incorporated into the concept of operations and standing operating procedures for the RTF. Throughout the deployment, these lessons were revised based on the experiences of the members of the Task Force to ensure they remained relevant to the situation and the operations being conducted. The work of the Defence Science and Technology Organisation on adaptive approaches in military operations was also utilised extensively.15

Those lessons that provided impetus for adaptation were documented so as to ensure that they would be passed on to subsequent deployments. This transfer of institutional knowledge was accomplished through frequent contact with follow-on units well prior to their deployment and the development of a web page with all RTF operational documentation made available to subsequent task forces. In addition, the staff of the 1st RTF assisted with preparations for the second and third RTF rotations.

The fact that the RTF saw ‘winning the adaptation battle’ as an absolute necessity was vital in ensuring that the unit possessed an ethos that allowed its members to identify weaknesses or problematic patterns and change these before they attracted unwanted attention. This systemic and formal approach to adaptation—reinforcing the informal approach prevalent in military units—was an important part of the RTF’s operational philosophy.

Where to From Here?

While the RTF has been successful in taking the first tentative steps in the rebuilding of Uruzgan, there is still much to be done. Based on the lessons of the past eight months, the RTF needs to build on its initial successes and broaden its reconstruction operations. Areas such as the development of indigenous capacity—including further technical training for engineers, works supervisors, surveyors and draftspersons for the Ministry of Reconstruction and Rural Development—require additional focus to ensure that they enhance the ability of Afghans to undertake their own reconstruction. Initiatives such as the offering of technical and educational scholarships to Australia or other countries would contribute significantly to the ability of Afghans to move beyond the reconstruction of their local villages to that of their nation.

The mentoring of local officials should also be expanded. Selective recruiting or contracting of experienced town planners and other experts in town maintenance and administration to provide local mentoring would significantly improve the capacity of the Afghan people to plan and build their own civil infrastructure. The involvement of Australian government and non-government aid agencies as part of a synchronised whole-of-government approach to reconstruction would substantially increase the capacity of the RTF and enhance the conduct of civil affairs in the province.

There is a critical need to increase support to capacity-building enablers. A logical next step is to combine physical construction with indigenous capacitybuilding through the development of education infrastructure. This infrastructure must include participation in initiatives such as the Education Quality Improvement Program that, among other objectives, seeks to develop teacher training schools and vocational training schools throughout Afghanistan. The construction of schools to train healthcare professionals and the provision of more police training centres must also be effected as a priority.

From an institutional perspective, the Army needs to further refine the conceptual model for reconstruction operations to achieve the most appropriate balance of resources allocated to physical and intellectual reconstruction activities. While this balance is likely to be different for every operation, a model for use as a start-state for the conduct of future operations would constitute a valuable addition to the current process.

Conclusion

The conduct of RTF operations has offered insights into the contribution of civil affairs activities to a holistic counterinsurgency campaign. While every insurgency is unique, the ‘cognitive realm’ focus of the RTF operation provides the counterinsurgent with a powerful tool to shift popular sympathy away from the insurgent. The type of operations conducted by the RTF and the manner in which they were conducted offer a highly capable, complementary function to the array of kinetic means currently deployed in Afghanistan, Iraq and other troubled areas. The mix of construction and security is a powerful combination and directly supports the conduct of kinetic activities in counterinsurgency operations. One 1st RTF officer commented dryly, ‘You can’t go around killing people and not promise them something.’16

Western nations are likely to face the challenges of counterinsurgency operations for some time to come. As David Galula noted in his book Counterinsurgency Warfare:

[W]ith so many successful insurgencies ... the temptation will always be great for a discontented group, anywhere, to start operations. Above all, they may gamble on the effectiveness of an insurgency-warfare doctrine so easy to grasp, so widely disseminated today that almost anybody can enter the business.17

If the forces of the West are to succeed in the conduct of counterinsurgency operations, they must have the ability to play a constructive role in those disrupted societies that will be the target of such operations in the future.

The conduct of reconstruction operations offers the affected population an alternative view of how they may live their lives, devoid of what Michael O’Hanlon terms the ‘ruthless and nihilistic character’ of contemporary insurgencies.18 Possessing the ability to not only kill the enemy, but to make him irrelevant to the populace must become a key tenet in the counterinsurgency fight waged by contemporary Western militaries. This certainly deserves more attention than it currently receives.

Endnotes

1 M. O’Hanlon, ‘A Ruthless Foe’, The Washington Times, 24 April 2007.

2 General D. Petraeus, ‘Learning Counterinsurgency: Observations from Soldiering in Iraq’, Military Review, Vol. 86, No. 1, January-February 2006, p. 2.

3 Commonwealth of Australia, LWD 3-8-4, Counterinsurgency, Australian Army, Puckapunyal, 1999, p. 1-10.

4 ISAF is a NATO-led coalition of thirty-seven countries.

5 Pashtunwali is an ancient code of conduct that governs the behaviour of Afghan people of Pashtun ethnicity. Its principal components are: hospitality, revenge, bravery, defence of honour and of tribal females.

6 Capacity-building is a consistent theme in the approach of various government and non-government aid organisations. One such organisation is AusAID, whose approach is described at <http://www.ausaid.gov.au/keyaid/people.cfm>. Andrew Natsios also lists capacity building as one of the nine principles of reconstruction in ‘Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development’, Parameters, Vol. XXXV, No. 3, Autumn 2005, pp. 4-20.

7 This involved the development of educational infrastructure based on consultation with the provincial Director of Education and interaction with the PRT Development Advisor under the auspices of the Afghanistan National Education Quality Improvement Program (EQUIP).

8 This title is a reference to an Australian television program of the same name in which a team of builders and landscapers would transform a suburban backyard in a matter of hours.

9 Malik is an Arabic word meaning ‘king’. In this context it refers to the tribal leader or chieftain.

10 Key terrain is defined as any locality or area, the seizure, retention, or control of which, affords a marked advantage. Key terrain is often selected for battle positions or objectives. It is evaluated by assessing the impact of its seizure by either force on the results of battle. Commonwealth of Australia, LWP-G 0-1-4, The Military Appreciation Process, Australian Army, Puckapunyal, 2001, pp. 3-16.

11 There was no adversary targeting of RTF projects during the tour of the 1st RTF.

12 United States Marine Corps, Small Wars Manual, 1940, pp. 1-17.

13 Counterinsurgency Operations, Australian Army, pp. 2-10.

14 J. Kiszley, ‘Learning about Counter-Insurgency, RUSI Journal, Vol. 151, Issue 6, December 2006, p. 16.

15 In particular, the work of Dr Anne-Marie Grisogono and her team was a significant influence in the approach adopted by the RTF. Grisogono, A, ‘The State of the Art and the State of the Practice: The Implications of Complex Adaptive Systems Theory for C2’, paper for the 2006 CCRTS; Grisogono, A, ‘Success and Failure in Adaptation’, International Conference on Complex Systems 2006.

16 Quoted in P. McGeough, ‘Winning hearts and minds is keeping the Taliban at bay’, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 February 2007.

17 D. Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, Frederick A. Praeger Publishers, New York, 1964, p. 143.

18 O’Hanlon, ‘A Ruthless Foe’.