Abstract

This article explores the implementation of ‘mission command’ in the complex operational environment of Al Muthanna Province, sourthern Iraq, by the commander of the Al Muthanna Task Group 1, using his experience as a case study. The author discusses the role of the leader in preparing, enabling and executing a mission command mind-set with a bias for action ‘amongst the people’ by implementing at all levels clear intent, trust and accountability.

The essential thing is action. Action has three stages; the decision born of thought, the order or preparation for execution, and the execution itself. All three stages are governed by the will. The commander will tell them (his subordinates) what he considers necessary for the execution of his will, but no more, and he will leave them freedom in the manner thereof which alone ensures ready co-operation in the spirit of the whole. There will always be details in which a commander must just hope for the best.

- General Hans von Seeckt, 19301

Success now, as it always has, rests with humans and the links and relationships between them. A human command system that generates ‘decision[s] born of thought’ and provides a robust freedom to act will enable military organisations to seize opportunities and perform in a coherent, coordinated decentralised manner. Systems based on centralised direction and rigid controls are not sufficiently adaptable. No amount of technology will ‘fix’ the weaknesses of the centralised approach. Humanity, reality and the ‘astonishingly complex environment’2 will simply not allow it. Armies must focus on people, mission command and ‘the essential thing’—enabling coherent, focused action in accordance with ‘the spirit of the whole’.

This paper is focused on how to enable ‘the essential thing’ at battle group or unit level. The first Al Muthanna Task Group (AMTG1) is used as a relevant contemporary operational case study.3 It is one example of the type of modern, complex and chaotic operational environments faced by Australian troops deployed around the world today.

The first section of this paper will describe why mission command4 is the logical, optimum and, perhaps only, practical philosophical approach for dealing effectively with complexity. The AMTG1 case study admirably demonstrates the ‘astonishing level of complexity’ faced by troops during modern operations. Using the case study as a tool, the key variables that generate complexity will be examined. These include terrain, threats, friendly force composition and mission aims and objectives. The purpose of the examination is to demonstrate and explain why mission command—’decentralised decision making within the framework of superior commander’s intent5’—is essential to mission success.

The second section will describe how a deliberate organisational framework can be fashioned to foster and support the application of ‘mission command’. Again the AMTG1 experience will be used to provide practical examples of the framework. The paper will describe the key intellectual, moral and physical components of a mission command framework at battle group level. The primary value of this paper is as a practical, if imperfect, mission command case study and discussion generator. My firm conclusion is that mission command is the key to enabling action and will maximise the chance of success in complexity. Alternatively, micro-management and over-control will almost certainly result in failure.

The Challenge of the Operational Environment: 'War Amonst the People'

We fight amongst the people, not on the battlefield.

- General Sir Rupert Smith6

Uncertainty, friction, humanity and violence are the enduring characteristics of conflict that combine to deliver complexity.7 A close examination of the AMTG1 operational environment provides an example of just how complex it can get. The environment is the context in which a force must operate and command systems must function. While each operational environment will be different, the common thread in modern operations is complexity. Following an examination of the case study, the paper will then examine the implications for command and action.

The Complex Environment: The Full Picture

The environment is ‘composed of physical, human and informational elements which interact in a mutually reinforcing fashion, leading to extremely high-density operating environments and enormous friction upon military operations’.8 Understanding ‘the full picture’ relies on appreciating the combined impact of the physical, human and informational environment. The AMTG1 case study ‘full picture’ provides a practical example of the context in which modern forces are required to act.

Terrain

Physical Terrain. Modern Western forces are increasingly operating in complex physical terrain as the threat groups use the environment for support and to hide, survive and strike at our weaknesses. The physical terrain encountered by AMTG1 in southern Iraq was diverse. The Al Muthanna Province includes wide variations in physical terrain—from close country along the banks of the Euphrates, to highly urbanised centres in the major cities, and pure, open sandy and rocky desert. For mobile security forces, transition through terrain types was a constant tactical challenge.9 The physical terrain represented a continually changing, irregular jigsaw in and over which all operations had to be conducted.

Human Terrain. The social and human dimension of a society is the central source of complexity. The human terrain of southern Iraq is a tremendous example of chaotic intricacy. The AMTG1 Area of Operations (AO) was conducted amongst a population of 500 000 people who were linked by an extremely complex Arabic maze of shifting and interrelated cultural, social, political, religious, tribal and family influences. It is markedly different to Australia and was utterly alien to the majority of our troops. At the most basic level, the language was different and our organic expertise in Arabic was limited. Cultural norms and conduct, such as the role of women, differ noticeably to that encountered in the West. In the constant cross-cultural exchange, a simple mistake could become an obscenity without the ‘guilty’ party even being aware of the error. Religion is a powerful influence, and religious leadership is closely entwined with political leadership. Located far from Baghdad, Al Muthanna is intensely parochial and regional in character. Local geography is important and the cities and towns of the Province have unique interests, organisations and identities. Tribal influence is crucial and pervades all aspects of daily life and action.10 The Province is politically fluid, active and prone to overheating at short-notice.

At the time, over 13 political parties were active in the Province, as well as a number of illegal organisations, such as armed militias and criminal organisations. A full range of new and evolving government, judicial, security and bureaucratic institutions were active and evolving within an incomplete and uncertainty policy framework. This complex human system, embedded in a jigsaw of complex terrain, was the AMTG1 ‘battlefield’.

Human complexity is not only a function of the domestic society. External stakeholders import their own significant contributions to complexity. First among these in the AMTG1 case study was the Multi-National Force (MNF). Like all large coalitions, the MNF consisted of a vast array of national troop contributions with different capabilities, characteristics and missions.11 Inside the AMTG AO, Australian, British and Japanese troops were overlaid, using up to three languages, each seeking linked but not identical goals. An extended range of government and civil agencies, such as various national diplomatic services and aid agencies, operated across the AMTG1 AO. Within this mix there were also a limited number of independent non-government agencies.

All these stakeholders were in constant, often completely independent, interactions with Provincial and Iraqi central government agencies. Amongst the milieu were private contractors, which range from large-scale logistic providers through to a multitude of private security detachments. This extended, external, and complicated mix fed directly into the local human system.

Informational Terrain. The final aspect of the complex environment was the informational system. While the remote, regional, rural Province of Al Muthanna struggled with the provision of the most basic essential services, it was fully networked into the global communications grid.12 Press networks were ever-present. While Western press were scarce, they employed a number of local ‘stringers’ who were armed with handheld video cameras and an open licence to rove. The Eastern press, notably Turkish satellite television, were on the ground and active. The Province had its own newspapers and television station. The sum result of the informational terrain was constant coverage and a network potentially linking all activities into the local, national and global pool of information in ‘real time’. For the friendly force, and almost everyone else, the eye of this network was constant and persistent. Given its instant, unpredictable feedback into the environment, the information network was capable of creating an unpredictable and diverse range of second- and third-order effects.

The Threat

And what are the clothes of the Mahdi Army? So that I can distinguish them from others. They don’t have a specific uniform. They are people gathered by love, and faith is their weapon.

- Moqtada al-Sadr, Spiritual Leader of the Mahdi Army Militia13

The threat groups confronted on many modern operations, including major combat operations, are increasingly irregular, unconventional and lethal.14 The threat groups faced by AMTG1 fit this model closely. Across southern Iraq, threat groups not only operated ‘amongst the people’; more often than not, they were ‘the people’. The threat was almost impossible for the AMTG1 to physically identify before it commenced offensive action and, if Moqtada al-Sadr’s comment above is to be believed, even he had difficulty identifying his own forces. Local and regional extremist groups, such as the Mahdi Army, pursued a variety of agendas through a combination of political, social, cultural and military means. In the south during 2005, the Coalition faced no concerted al-Qaeda–led Sunni extremist insurgency.15 Nevertheless, the possibility of such an insurgency remained a constant factor to be considered and countered. Threat elements pursued a classic guerrilla methodology married to the power and lethality of modern technology.16 Threat tactics emphasised dispersion, ‘fluidity of force’, low profile and avoidance of battle.17 They operated ‘like a vapour [that would] offer nothing material to the killing’.18 AMTG1 faced a complicated patchwork of heavily armed, largely local militia forces operating literally ‘amongst the people’. It was war by the few, but was dependent on the support of the many.19 Interaction with the threat took place in the context of the complex environment.

Friendly Force Composition

Complexity is not only a by-product of the physical, social and informational terrain and the threat profile. Modern security missions require the case-specific creation of combined joint interagency task forces (JIATF) to achieve designated missions within a complex environment. These teams aim to ‘incorporate all elements of national power in an integrated framework, tailored and scaled to the requirements of specific a mission’.20 The intent is to build a force that is able to ‘control the perceptions and behaviours of specific population groups’ and not merely apply force.21 JIATFs are, therefore, rarely standing organisations or groupings. They are custom-made and case specific.

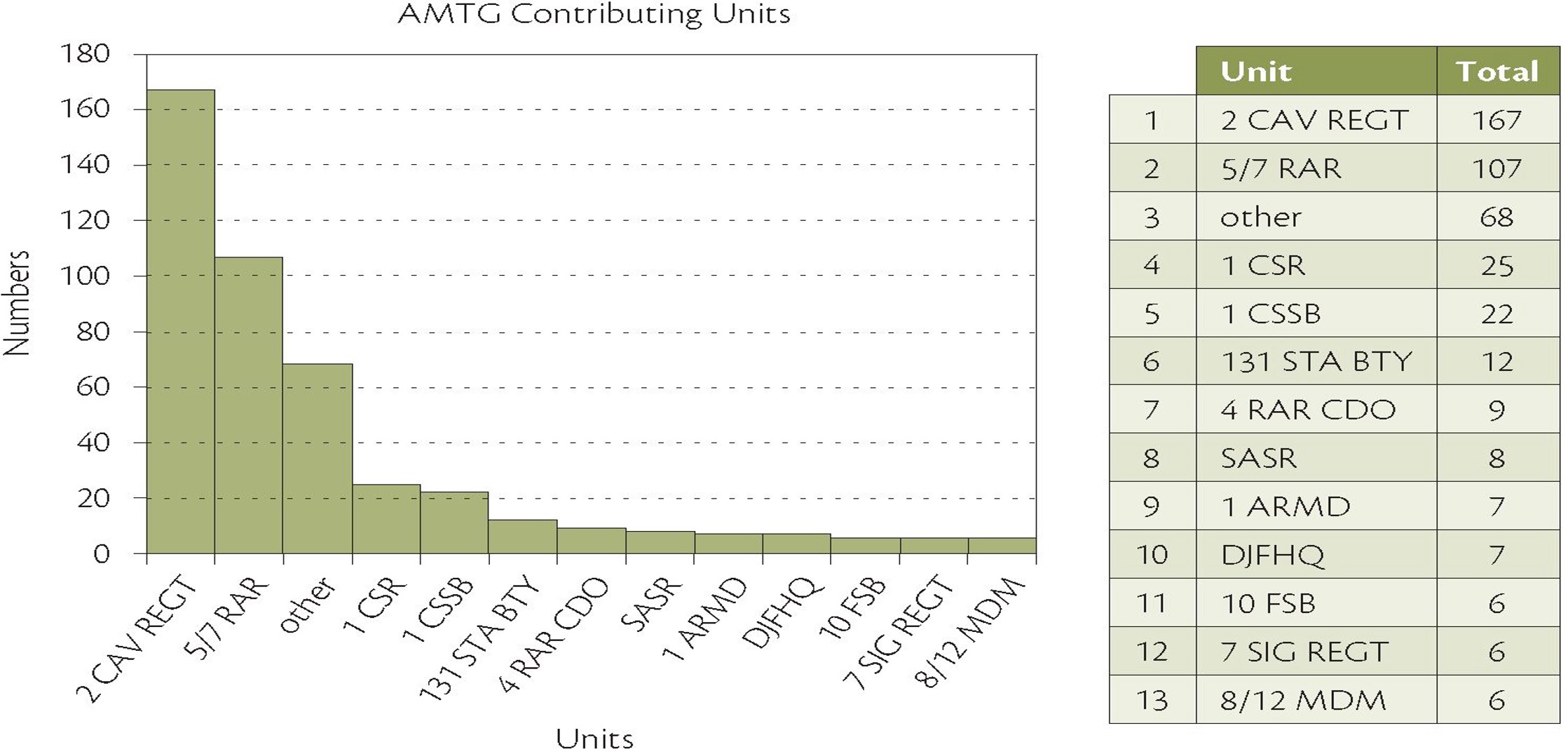

AMTG1 is one example of a modern battle group–level JIATF. It was not a standing organisation and was non-traditional in structure. It incorporated a broad range of capabilities drawn from joint, Defence and national resources. It consisted of 450 personnel from two Services, 56 Army units and 19 Corps. The considerable diversity is reflected through an example table shown below at Figure 1, which shows the sources of AMTG1 Army personnel. The force also included a selected range of specialist civilian personnel. AMTG1 was a diverse, unique grouping of capabilities that were rapidly concentrated, formed and deployed.22 The composition and rapid deployment of a custom-made force was essential, but generated unavoidable internal complexity and friction.

The Complex Environment: The Implications for Command

For the soldier on the ground, the environment is quite simply a sea of complexity. Situations rapidly develop, constantly change and demand immediate case-specific responses. The problems encountered are never purely military or tactical; they are also social, cultural, legal, moral and political. Drills and templates provide assistance and guidance, but success requires thinking, decision-making and adaptation to the specific circumstance. A constant, recurring theme of modern operations is that complexity means that ‘the possible permutations of all ... interactions are innumerable’.23 Success, therefore, relies on shaping and influencing outcomes and then quickly adapting to and exploiting those outcomes. War amongst the people requires soldiers who are face to face with the people to have the will, means, authority and freedom to act to achieve the mission. The environment demands mission command.

Missions and Methods

AMTG, as part of UK led Security Sector Reform, is to conduct security operations and provide training and adviser support to the Iraqi Army in AL MUTHANNA province for at least 6 months from 3 May 05 in order to enhance the security of the Japanese Iraq Reconstruction and Support Group and support the Governorate of AL MUTHANNA province to realise the process of UNSCR 1546 and transition to Iraqi self reliance.

- AMTG1 Mission Statement24

Missions on modern security operations almost always seek objectives that are beyond purely military results. This has the effect of broadening the range of tasks to be performed, increasing the types of capabilities that are deployed and requiring the employment of sophisticated methods that are tailored to the complex environment.

Figure 1: Army Units contributing more than five members to the AMTG

The AMTG1 mission (detailed above) provides an example of a mission that generates a need for sophisticated and disciplined methods applied by a force armed with a range of capabilities. AMTG mission success would ultimately depend on collective local community opinion.25 The focus was not the destruction of the threat, but rather the defeat of their intent to use illegal and violent action to achieve their ends. Success could be achieved as much by indirect means as through any clash of arms. The AMTG1 was, therefore, unavoidably required to execute a broader range of tasks than those required of a purely conventional military security task. It also required a sophisticated sensing of changes in the environment and quick adaptation to exploit opportunity. While the case study is unique, it bears similar traits to missions and requirements underway from East Timor to Afghanistan.

The nature of modern missions and complex environments demands decentralised action and adaptability. For example, the AMTG1 environment and mission demanded that no set patterns be developed in order to dislocate the threat. The force was required to operate in dispersed, small, but powerful groups that could survive and defeat an attack, yet not alienate the locals through unnecessary disruption to, and interference in, their lives. AMTG1 had to establish and sustain a continuous, open, face-to-face dialogue with people at every level across our AO. The force, therefore, had to act effectively in a dispersed, decentralised, face-to-face manner.

Decentralised and sophisticated methods, reliant on adapting to circumstance, require a binding ‘glue’ to ensure that action taken is coherent and directed towards a common end. A centralised, hierarchical system relying on detailed direction from above has limited adaptability, responsiveness or situational awareness to support a force operating in a 24-hour, dispersed, mobile roles. The essential glue that enables coherent action is not a piece of technology or a detailed web of predictive rules, but rather the establishment of an adaptive human system of mission command. The difficult part is establishing a mission command framework that enables effective, coherent action.

Building A Mission Command Framework

Given the importance of adaptability and the pressing need for effective decentralised action, the key issue becomes how best to build a mission command environment? This paper proposes that effective mission command relies on the establishment and nurturing of a mission command framework. The framework must consist of a series of intellectual, moral and physical components that together provide freedom of action and support to subordinates within boundaries.

Intellectual Components. An effective mission command framework relies on a clearly articulated and understood philosophy of mission command. This idea must then be clearly explained and articulated across the entire organisation. For example, AMTG1 had a short description of the philosophy of command that would apply on operations. The philosophy included the five specific individual characteristics required of the soldiers, non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and officers of the battle group:26

- Mission Focused/Task Orientated

- Imbued with a culture of mission command and a bias for action

- Tactically and technically excellent

- Highly Disciplined

- Adaptable

The command philosophy provided the behavioural rules against which all decisions, plans, training and actions would be developed and then assessed. In AMTG1, action was emphasised as a critical idea and was a mandated behavioural requirement:

The AMTG must have a bias for action. Individuals must independently act to solve a problem and achieve the mission in a timely manner based on the available information and resources. Decisive, determined action, based on the commander’s intent and targeted against the enemy’s critical vulnerabilities must be the hallmark of AMTG operations. Uncertainty is a constant, always act decisively.

A philosophy that describes mission command and explains what is important is the first and critical element of any mission command framework.

Mission Command relies on a clear understanding of the commander’s intent across an organisation. The intent must be articulated, explained and updated regularly. This is formally achieved through the promulgation of an operations order. Perhaps more importantly it was constantly reinforced through the ‘battle rhythm’ of an organisation.27 Intent became the issue of discussion throughout the organisation. In AMTG1, this was achieved through a variety of formal and informal means. Commanding Officer’s (CO) hours with the soldiers would begin with a discussion of the mission, tactics and the threat. Visits, sub-unit training, meals, and tactical operations all provided occasions for commanders (at every level) and soldiers to discuss and understand intent. One excellent example was the regular ‘sand table’ tactics training held by Combat Team Eagle, where intent was an open forum topic for discussion and suggestion by all ranks. Intent must become a ‘living’ idea that is a constant topic of discussion, and must be deeply understood.

A clear intellectual accountability framework, understood by all, is vital. Accountability is essential, as it holds subordinates and the entire organisation to the mission. Each individual must be held accountable against his appropriate level of responsibility. Therefore, it is vital to agree on what constitutes an error.

A considered and collective definition of what constitutes a mistake is fundamental. To enable a culture of mission command, a mistake should be defined as a decision made without systematic regard for the commander’s intent or the mission. It must not be seen as an action that generates an adverse or negative result. Friendly force action is but one element in a complex system; the end consequences will be the result of multiple inputs and influences. A mistake, therefore, may well be both a decision leading to an action or the absence of a decision that results in a lack of action. It is important to recognise that a failure to act may be as significant as any decision to act. Where the actions are clearly connected with intent but the results are adverse, subordinates must be strongly supported in their actions. The incident or action should be reviewed and analysed with a view to improving performance. Coaching or retraining may be initiated, or the actions taken may be reaffirmed and validated. Where this definition of a ‘mistake’ is the norm, and the commander’s intent is the yardstick, the organisation will automatically self-correct and adapt at every level to achieve a common purpose. Action is, therefore, likely to be coherent, focused and encouraged. Subordinates will feel empowered to take action in uncertainty when they are certain that it passes the assessment against the intent test.

In AMTG1, the responsibilities for the actions of a force were the responsibility of the immediate commander, who was held accountable against the intent and the mission. Where the commander acted outside the boundaries of, or contrary to, the intent articulated, he would be formally disciplined and/or removed from his post. This was required on a small number of occasions and it was absolutely essential in order to build trust, preserve freedom of action and reinforce a disciplined application of mission command. Conversely, where a decision is taken in accordance with the intent and the mission, the subordinate must be supported and the commander must accept responsibility and ‘own’ any adverse consequences that arise from that action. This approach grows trust, liberates subordinates to act, and binds every level of action to the mission.

Effective accountability fundamentally relies on systematic command supervision. As a general rule, supervision needs to be constant, multi-level and available to subordinates. It should be helpful and should not be delivered as a superior, auditstyle oversight. Importantly, supervision should be personal, direct and detailed. This requires commanders at all levels to operate forward in the field rather than within the security and connectivity of the firm base. This ensures that the key supervision is located in the optimal location for any given plan.

Moral Components. Trust is the essential moral component of mission command. Commanders must accept and own risk in order to demonstrate trust. As trust must flow both down and up, it depends on knowing individuals and understanding how they think and act.

As General von Mellenthin accurately observed, ‘Commanders and subordinates start to understand each other during war ... the better they know each other, the shorter and less detailed the orders can be’.28 This proved to be an observation relevant to AMTG1. The development of trust and understanding was facilitated by a combination of supervision and close interaction between commanders at every level. This is a face-to-face, human business rather than a hierarchical, formal process achieved through constant email contact. AMTG1 deliberately lived, worked and went on leave in its small team groupings—both section and patrol. Trust develops and spreads like a virus—upwards, outwards, downwards and cross ways. Trust cannot be mandated, directed or wished into being.

Where trust is breached, or not developed, personnel must be removed or placed in positions where close supervision is possible or where the risks are minimal. Breaches of trust cannot be tolerated, no matter how small, as it is the true currency that underpins all mission command-based organisational action. On a number of occasions, breaches of trust within AMTG1 resulted in disciplinary action and the removal of personnel from appointments, or modifications to the level of freedom of action assigned. Failure to act on breaches of trust, at any level, will seriously undermine mission command. This means that the rule must apply to all, equally, top to bottom. Rank, age, and specialty can offer no sanctuary.

Physical Components. A physical control framework is required to support effective mission command. A control framework must be established to provide security, confidence and support to junior commanders. The control system must assist decision-making and command. It must be responsive and adaptable to changes. Commanders must be empowered to modify it and there must be a constant dialogue on the boundaries of action and control measures. Senior commanders should speak directly and regularly to junior commanders. The vertical hierarchy and position is less important than the mission: when they know they need to, junior commanders must be encouraged to speak directly to senior commanders. The key to an effective mission command is the construction of a co-ordinating framework that is highly accessible to subordinates, responsive to the environment and capable of adapting quickly.

Empowerment of the staff to make decisions, support subordinates and to support the execution of the mission is the aim of an effective control system. In AMTG1, the S3 became the lead control officer. His core business was the regulation and management of the commander’s intent and the execution of the mission. Jokingly, and appropriately, he was called ‘The Intent Policeman’ and constantly patrolled the mission and intent. In AMTG1, the S3 did not act as the deputy commander, but was instead tasked with building, servicing, repairing and modifying the control framework. He was a key adviser to all commanders and did not compete with them. All branches of the BGHQ staff effectively served the operations staff and the S3. They were vital to feeding and sustaining the framework, keeping it up to date and triggering the need for change or adjustment. The tools of the staff were fragmentary orders, control measures and the transmission of key information between commanders, across the battle group and outside to the broader Coalition.

Formal orders provide the behavioural rules and guidance to allow subordinates to act inside an agreed framework and give them freedom of action. In AMTG1, the operations order formed the bedrock operational guidance and ‘law’ that guided all behaviour and decision-making. It was effectively a ‘one-stop shop’ for formal policy. The AMTG1 operations order included issues as diverse as detainee policy, the Rules of Engagement (ROE), safety policy, training policy, compensation and act of grace payments and discipline. It was revised and adjusted regularly, with five separate versions being issued. Against this order were issued Fragmentary Orders. All tactical and administrative activities were instigated and covered by formal written orders. When time was limited, orders were issued verbally and the written order followed shortly thereafter. This methodology empowered the staff to make actions against the formally stated intent. As they were charged with executing the operations order, it needed to be comprehensive enough to guide decision-making. Orders were to be complied with and were written to confirm intent, describe freedom of action and guide behaviour and decision-making.

The operations order should set the rules for behaviour rather than focus on developing predictive details on specific actions in certain circumstances. In the case of AMTG1, behaviour and responses to unexpected situations were critical. The AMTG1 needed to operate in a low profile way, so the AMTG1 was always seeking to be in ‘the corner of their eye’ rather than directly in the faces of the local people. All activity had to be conducted against the reality of the local cultural norms, not in accordance with our own world view. From this, ‘consent’ could be built. Therefore, the operations order and intent emphasised ‘rules of behaviour’ being applied on a case-by-case basis. The three rules are:

- Always Low Profile—’Corner of their Eye’

- Always Culturally Aware

- Always Highly Disciplined

When followed, even in difficult circumstances and against powerful threat information operations, respect and support would almost always grow. Subordinates could take the rules and apply them, as required, to whatever particular circumstance arose.

The organisational battle procedure must serve subordinates and act to continually update, assess and modify intent and control arrangements as required. AMTG1 evolved a systematic operational cycle that focused on a constant assessment and update of intent and adjustment of the control framework. This became the primary purpose of the Daily Operations Update, which was a ‘short’, daily operational assessment and discussion forum. This was supported by a deliberate seven-day planning cycle that identified and resourced known tasks seven days out. This provided maximum warning and planning across the sub-units. The effect of a disciplined operations and planning cycle is a coherent, constant control across a battle group. It supports and enables decentralised, detailed execution, and supervision at combat team level and below. Ideally, it should ideally be focused downwards and on execution.

The development of effective Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) reduces friction and allows rapid adaptability to changing situations. SOPs should therefore be threat-, environment- and capability-driven. They must be discussed, argued and improved. In AMTG1, the operations staff owned the SOPs and modified them in consultation with the entire battle group, most notably the combat teams. The duty of the combat teams was to ‘road test’ SOPs and to consistently question and improve them.

Shared situational awareness, supported by an effective command information system (CIS) network, is critical to maximising the chances of coherent action. A mission-command control framework must have the aim of furnishing its people in the field with timely and effective intelligence that leads to high levels of situational awareness. Navigating the flood of information, finding the key pieces and interpreting them effectively are not simple tasks. This process requires a careful, intimate linkage between the intelligence and operations staff, both of whom must unwaveringly serve all commanders from patrol to battle group level. A culture of service by the staff, both upwards and especially downwards, is essential and is rarely automatic. This is an old idea. To quote General Sir John Monash: ‘The staff officer is the servant of the troops ... this was the ritual pronounced at the initiation of every staff officer’.29 The development of a responsive intelligence cycle and process that serves the soldiers in the field requires disciplined staff processes, close cooperation and dogged, hard work by battle group level staff officers who must be constantly supported by close-command supervision.

The control framework must have at its heart an effective technical network of communications. While there is no substitute for face-to-face orders, a supporting communications network is a key component to enable mission command. At battle group level, secure voice is critical, as command and intent can be forcefully transmitted through language, tone and expression. Email alone is therefore an inadequate method of communication. AMTG1 was equipped with a range of effective systems that enabled mobile, secure communications. Redundancy is important; as are multiple communications means. Communications will break down due to both the threat and the environment, and the control framework must support action when there is no communications.

A strong organic discipline and personal support system is the backbone of any effective mission-command system. Ideally, discipline on operations becomes the business of all ranks that ‘self-police’ and sustain collective discipline without constant command intervention. Discipline is everyone’s business, not just officers or senior non-commissioned officers (SNCOs). The discipline system must be simple, clear, timely, just and operate without favour. A key component, often overlooked, is the design of ‘the rules’ and their assigned importance. If rules are broken, discipline must be enforced. It is, therefore, vital that the rules are sensible, relevant and linked to mission outcomes. Any rule that commanders are reluctant to enforce should be modified or removed. Like SOPs and the other components of the control framework, the rules governing conduct must be carefully designed and constantly assessed. If the rules are sensible and enforced without fear or favour, they promote credibility and allow trust to develop.

The discipline system must be supported by a command-driven welfare network in which everyone supports each other. Key appointments, such as the doctor and padre, are vital as they perform the role of both semi-independent morale (and discipline) ‘thermometers’ and advisers to all. High operational tempo and limited opportunities to rest demand a careful, constant assessment by all deployed personnel. This is the core business of commanders. In AMTG1, the use of enforced rest and short-term job swaps were two simple methods employed to manage discipline and morale. The authority of formal military discipline is the ultimate legal power that holds all to the mission and the required standard of conduct. It must be both credible and strong.

Systemic learning through constant assessment linked to training enables organisational adaptation. Training is the mechanism to formally improve, adapt and codify modified action. The retention of core skills and individual and collective proficiency are critical to confidence and trust. Training, revision and the testing of new and emerging ideas must also be part of the operational cycle. This requires not only familiar training (such as weapons handling and shooting), but a constant focus on tactical decision-making. The use of the tactical quick decision exercise, whether formal or informal, forces a debate on intent and action. Over time, this style of training links approaches and thinking while simultaneously generating critical analysis of current methods and tactics. For example, AMTG1 used deployed tactical low-level simulation and deployed Coalition (and DSTO) operational analysis teams to support assessment, learning and adaptation. Part of a mission-command control framework must be a deliberate, planned training program linked with a culture of formal and informal discussion and learning.

As mission success is the focus of mission command, an organisation needs to understand whether or not it is on the path to success. This requires the careful design of measures of effectiveness and a rigorous performance tracking methodology. This element of a control framework was initially missing for AMTG1 on deployment and answers were not readily found in doctrine. Over a period of time, a system of assessing progress was developed. This modified system allowed for the measuring of progress and the adaptable allocation of a full range of resources and capabilities, (kinetic and non-kinetic) to influence outcomes. This process also demanded that AMTG1 gain an understanding of the complex environment in which it was operating. What action induced what responses? What were the levers of influence in society? How was local consent reinforced or undermined? This tracking and auditing function is vital (for both positive learning and adaptation) in order to achieve the desired result.

Conclusion

In the 21st century, action remains the essential thing. Yet there are tremendous pressures to attempt to centrally control, direct and limit action. There is often a temptation to delay action, or indeed not act at all, given both the intense scrutiny and the potential adverse and unpredictable outcomes. This is not the path to success in complexity and against threats that recognise and exploit the operating environment and constraints in and under which Western forces operate. Effective, focused action at the lowest level remains the key to success. A network of intent that binds all to the mission is the logical and optimal approach to the challenge of complexity and chaos. It also allows a force to seize and exploit fleeting opportunities and to target the vulnerabilities of hard, committed and intelligent adversaries.

The key to effective, focused action is mission command. The philosophy of mission command must be believed and nurtured. To be effective, it must be built on the intellectual components of clear intent, trust and accountability. The central moral component is trust. A physical control framework must also be established to support decision-makers at every level, especially those in the midst of chaos and in close contact with the adversary. While every circumstance is unique, this paper has sought to identify some of the enduring components common to any physical, moral and intellectual framework of mission command. Mission command offers one way to enable effective action and to create a human network that ‘ensures ready co-operation in the spirit of the whole’.

Endnotes

1 General Hans von Seeckt, Thoughts of a Soldier, Ernest Benn Limited, London, 1930 pp. 123–30.

2 Lieutenant General J.P. Storr, ‘Command and Control within the Land Component’, Journal of Battlefield Technology, Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2000, p. 19.

3 From 24 April 2005 until 10 November 2005, the Al Muthanna Task Group (AMTG1) conducted 24-hour combined arms security operations, including 2359 discrete tactical tasks, for a total of 191 days in the high threat, complex operational environment of southern Iraq. This paper will use the AMG1 experience as one specific case study.

4 Mission Command is a philosophy of command and a system for conducting operations in which subordinates are given a clear indication by a superior of his intentions. The result required, the task, the resources and any constraints are clearly enunciated; however, subordinates are allowed the freedom to decide how to achieve the required result. Land Warfare Doctrine 0.0, Command, Leadership and Management, Department of Defence (Australian Army), Canberra, 17 November 2003.

5 Storr, ‘Command and Control within the Land Component, p. 19.

6 General Sir R. Smith, The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World, Allen Lane Penguin Books, London, 2005, p. 269.

7 Australian Army, Future Land Operating Concept: Complex Warfighting, <http://www.defence.gov.au/army/lwsc/Publications/complex_warfighting.pd…;, p. 4.

8 Ibid, p. 6.

9 Patrols of the AMTG would encounter these physical environments, and combinations of all three, within five kilometres of the forward operating base. Large infrastructure, such as highways and bridges, combined with significant man-made and natural obstacles, created a complex physical environment where choke points, routes, and observation points combined to create a complicated tactical jigsaw for both friendly and threat forces. It is difficult to imagine a physical environment more different from Australian training areas or one that could provide a greater series of rapid fire tactical challenges to any mobile security force.

10 For example, any police response to an incident would begin with an assessment of which tribes were involved in order to ensure the responding police could moderate the situation rather than complicate it through their own tribal identity. After 6000 years, an enduring, unwritten heritage of interaction between tribes, clans and families played a role in all social interactions.

11 AMTG1 flanking formations included troops from five nations who spoke four different languages. Liaison took place across three international and four Provincial borders. Two major Coalition routes ran through the AMTG AO, which resulted in a constant transit of almost all the remaining troop contributing nation force elements.

12 For example, most male locals owned at least one mobile phone and the network was modern, involved multiple service providers and offered extended local and international coverage. Cable television networks fed directly into the Province and could be found as far afield as the most remote desert police station. Internet services were also widely available.

13 ‘An Army of One: Iraq’s Moqtada al-Sadr on his men, his mind-set and when America should go’, Interview by Scott Johnson, Newsweek, 8 May 2006, pp. 22–3.

14 For example, during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Coalition forces met fierce resistance from irregular forces and only experienced limited direct confrontation with conventional forces. Studies such as COBRA II reveal that this was unexpected and that Coalition forces, especially at the operational level, were slow to adapt to the reality of the threat. M. Gordon and B. Trainor, COBRA II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq, Atlantic Books, London, 2006.

15 This was largely due to the efforts of those in the local community who were determined to prevent mass casualty attacks and extremist violence mounted by foreign fighters or Iraqis from other regions—all collectively viewed as ‘outsiders’ by the local majority.

16 Threat groups employed a range of highly lethal weapons, such as highly sophisticated Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and improvised indirect fire rocket attacks, in order to maximise their impact and minimise their chances of being decisively engaged. In all actions, threat groups exploited the environment, local support and knowledge in order to cover, assist or allow their actions to take place.

17 During the six months of the AMTG1 tour, it is worth noting that, of the seven deliberate threat attacks against Coalition forces in Al Muthanna, only two involved direct fire ambushes. Of these only one was assessed to be a deliberate, planned attack, while the other exploited a fleeting target of opportunity.

18 T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Wordsworths Classics of World Literature, Ware, Hertfordshire, 1997, p. 182.

19 B. H. Liddell Hart, Strategy, Meridian, New York, 2nd revised ed., 1991, p. 367. In 1954, Liddell Hart published the last version of his classic book on strategy with an additional chapter devoted to Guerrilla War. In it he describes the classic guerrilla or subversive strategy. It demonstrates that this approach is not new and remains relevant to modern operations in Iraq. He assessed that this approach ‘tends to be most effective if it blends an appeal to national resistance or desire for independence with an appeal to a socially and economically discontent population’. AMTG1, therefore, confronted a ‘classic’, if fragmented, guerrilla or subversive threat strategy.

20 Complex Warfighting, p. 14.

21 Ibid.

22 Deployment time from Government announcement in Australia to the commencement of operations in Iraq was 10 weeks. The AMTG1 drew personnel and equipment from across Australia.

23 Major J. P. Storr, Alternative Concepts For Battlefield Command And Control Organisations’, United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, paper presented to the 1999 Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, Command and Control Research Program, US Naval War College, Rhode Island, 1999, downloaded from: <http://www.dodccrp.org/events/1999_CCRTS/pdf_files/track_5/026storr.pdf…;.

24 AL MUTHANNA TASK GROUP (AMTG-1) Operations Order 02/05 OP CATALYST dated 25 May 2005. (The full document is SECRET)

25 The commanding general viewed the ‘consent’ of the local populace for Coalition action as crucial to mission success. He assessed that ‘consent’ was heavily dependent on, and intertwined with, ‘the legitimacy and responsibility of the Iraqi government’. Commanding General’s Directive To Multi-National Division (South-East), March 2005. (The full document is CONFIDENTIAL)

26 These characteristics are now included in developing Australian Army cavalry doctrine.

27 Daily operations briefs allowed for a continuous update and assessment. Extensive liaison linkages across national and Coalition forces enabled an ongoing assessment of intent.

28 DePuy, Balck and von Mellenthin on Tactics: Implications for NATO Military Doctrine, Universitaet der Bundeswehr, Munich, December 2004, p. 19.

29 General Sir J. Monash, The Australian Victories in France in 1918, Hutchinson and Co, London, 1920, p. 295.