Climate Change and Army Personnel

In a 2024 article in the Australian Army Journal, Dr Albert Palazzo was necessarily blunt in his assessment of the impact of climate change on the future characteristics of war, stating that ‘Australia and the ADF will have to adapt if the nation is to meet the demands of operating in a more violent and decisive climate change era’.[1] Unfortunately, Palazzo stands with just a handful of others in articulating the extent to which climate change will affect the Australian Defence Force (ADF). As has been the case for much of the last century, the understandable default of military academics and strategists seems to be authorship on topics perceived to have a greater appeal to the usual military audience, such as those focusing on military operations, acquisitions, technology, and national security.

In this article, defence policy and the discussions of several security analysts will be extended to consider the practical impacts of climate change on the members of the Australian Army. In particular, the article will focus on the effects of climate change on individual soldiers, their families, and the training and career systems. Importantly, in line with advice from the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, this article considers climate change to be inevitable.[2] Therefore, the discussion does not speculate about whether there may be impacts on Army, but takes the perspective that there will be impacts—with the only variable being when those impacts will occur.

Summary of the Strategic Literature

The Defence Strategic Review (DSR) dedicates just five brief paragraphs (about half a page) to the topic of climate change; three of them lament the concurrency of the ADF’s contribution to disaster relief against the provision of military capability. In this context, the issue of climate change itself is not directly addressed. Further, while the DSR states that ‘[c]limate change is now a national security issue’,[3] it is noncommittal as to the degree to which this is the case. Using speculative language, it states: ‘If climate change accelerates over the coming decades it has the potential to significantly increase risk in our region’. At least one commentator has noted that the language of the DSR is not useful given that it is a broadly accepted fact that climate change will accelerate and it will increase risk; speculative language serves to diminish the immediacy of the threat[4] and its moral implications.[5]

Among security commentators, there is broad consensus that climate change poses ‘a national security threat to Australia through the stability of the region and national capacity to respond’.[6] There is a consistent theme recognising the climate/security nexus: ‘climate change effects lead to environmental impacts, and environmental impacts create social impacts, which lead to security implications’. Influential authors (including those affiliated with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute[7] and the Australian Security Leaders Climate Group (ASLCG),[8] the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,[9] the United Nations Security Council[10] and a Senate standing committee[11] take this view. Indeed, the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade concluded that there is ‘consensus from the evidence that climate change is exacerbating threats and risks to Australia’s national security’.[12]

While the national security threat posed by climate change is broadly acknowledged, some writers lament that ‘the ADF has only limited awareness of the extent of the disruption and military challenges that climate change may create’.[13] Indeed, there remains ‘a refusal to accept the size and immediacy of climate risk in 2024’,[14] an observation that extends to the impact of climate change on ADF members themselves. In an effort to redress this situation, Palazzo explains the implications of climate change in practical terms for warfighting strategy. This includes the need for a larger ADF, emphasis on self-reliance, participation of the entire Australian citizenry, and consumption of national wealth. Palazzo has ominously surmised that ‘war will resume its place as one of the great forces for human decision-making’.[15]

Overall, security and climate change are rarely written about by Australian security specialists. It is significant that Palazzo’s contribution on climate is unique among the numerous articles in the Australian Army Journal. Notable too is Michael Evans’s nuanced opposing view in the Australian Journal of Defence and Strategic Studies; he argues that there is no direct causal link between climate change and conflict.[16] Among the dozens of other defence and security advocacy groups and think tanks, only one is focused specifically on climate change and national security in the Australian context—the ASLCG, whose members include a former Chief of the Defence Force and a former Vice Chief of the Air Force.[17] Others provide a regional focus, as the Australian Strategic Policy Institute does through its Climate and Security Policy Centre.[18] Overall, despite the dozens (or hundreds) of articles written every year by Australia’s military strategists, the paucity of discussion on a change that is inevitable, in favour of speculation on hypothetical strategic scenarios that may never occur, is both disappointing and alarming.

Significantly, to the degree that Australian-focused articles and reports exist, they are written without the benefit of the classified 2022 Office of National Intelligence climate and security risk assessment, which would greatly add to national debate and understanding (and of which the ASLCG has called for the release of an unclassified version).[19]

Australia’s Changing Climate

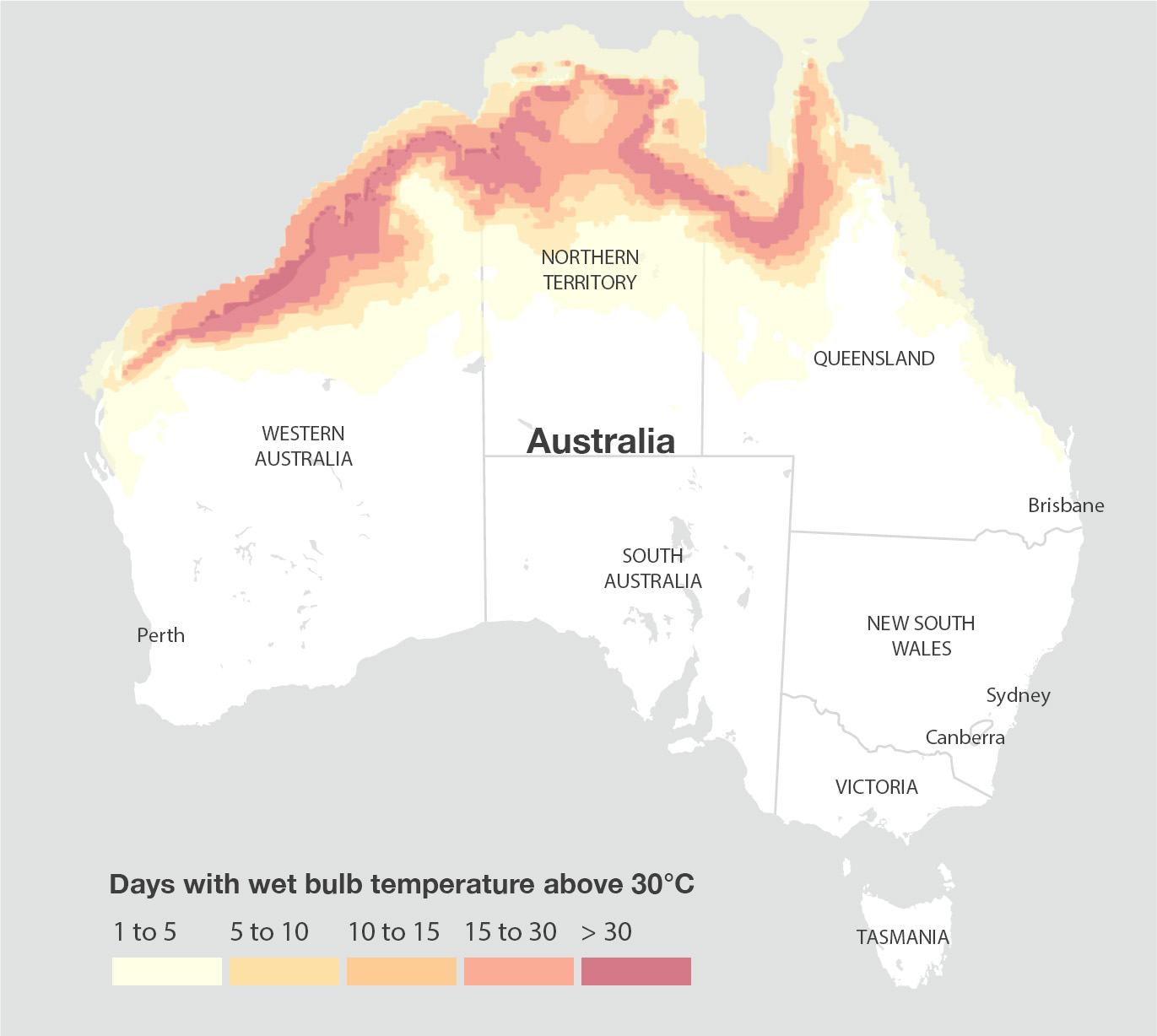

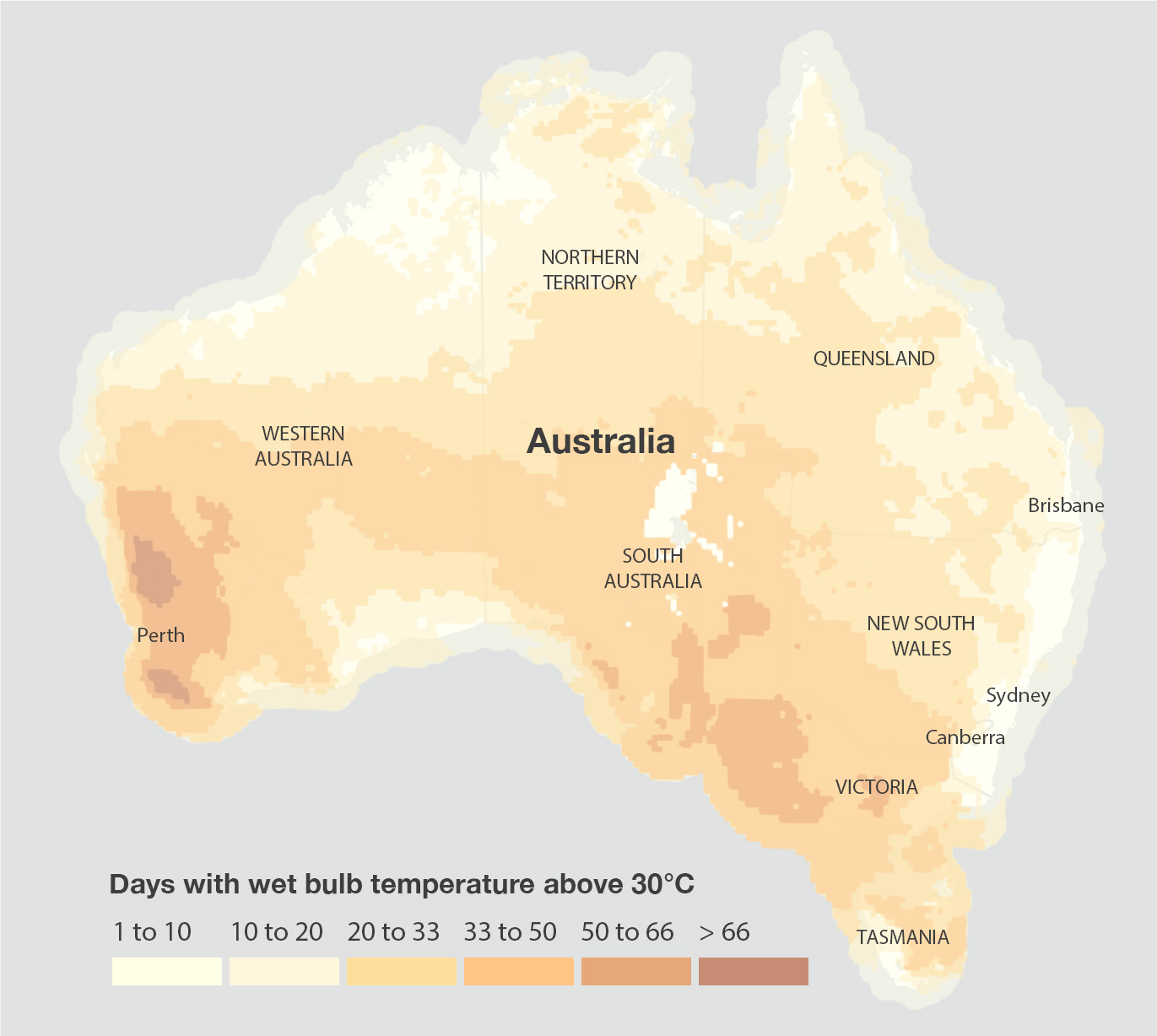

It is inevitable that there will be more extreme weather events in Australia. However, Army has not yet considered how the regions affected by these events will overlap areas of large Army populations. For example, modelling[20] shows that in military locations in the north of Australia there will be a significant increase in the number of days when the wet bulb temperature exceeds 30°C (Figure 1).[21] The ASLCG points to the resulting extreme living difficulties that will confront members and their families posted to these locations in their efforts to conduct normal, everyday activities.[22] It is predicted that by 2050 some urban locations such as Darwin will experience between 66 and 129 more days over 35°C each year, as global average warming reaches between 2°C and 4°C (113 to 176 days per year in total).[23]

Figure 1. Days with wet bulb temperature above 30°C[24]

Image credit: Peter Aldhous, based on data from Probable Futures[25]

Extreme heat events are not the only problematic consequence of climate change. Modelling also predicts an increase in the annual likelihood of drought, exceeding 50 per cent in many geographic areas of Australia (Figure 2).[26] This situation will increase the impact of dust and exposure on equipment, decrease foliage and its stability, increase the likelihood of irreparable environmental damage to training areas, and threaten the viability of some training areas for continued heavy vehicle use, including manoeuvre-based activities. As identified by Palazzo, ‘platforms optimised for environmental conditions that no longer exist may have to be modified or scrapped’.[27] Finally, the same modelling indicates that almost all of Australia can expect increased rainfall should there be the one in 100 years storm in a world warmed by 3°C. Such an outcome would disrupt all ADF training activities in proximity.

Figure 2. Annual likelihood of extreme drought[28]

Image credit: Peter Aldhous, based on data from Probable Futures

Climate Change and Army

So far, aside from a few localised extreme weather events, Army has been lucky to avoid much of the worst of climate change; most has occurred away from Army’s major bases. However, already this century there have been two major floods affecting members posted to RAAF Base Amberley (and nine floods in the greater Ipswich area);[29] Townsville was flooded in 2019;[30] and road access between the Northern Territory and South Australian elements of 1 Brigade were cut during flooding in January 2022.[31] Between February and April 2022, Defence Housing Australia reported 565 flood-damaged properties in south-east Queensland and parts of coastal New South Wales,[32] and in April 2024 Holsworthy experienced extreme rainfall that closed training areas. Luck will soon run out. In the next decade (and beyond) Army can expect an increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events in major unit locations and training areas. Drought, floods fires and prologued heatwaves will have a direct impact on training, training outcomes, families and ultimately capability.

Training Area Availability

One of the more obvious consequences of climate change will be its effect on Army’s training areas and facilities. Major training areas including Mount Bundy, Bradshaw and High Range will be unavailable for longer periods due to inaccessibility, infrastructure damage, terrain alteration, or more frequent occasions where the temperature exceeds wet bulb globe restrictions.[33] Remediation of damaged infrastructure and terrain will close specific areas for lengthy periods. Live-fire ranges will face more frequent heat-related closure due to fire risk, resulting in increasing demand for the limited days available and prioritisation of use. Not only will there be constraints on a unit’s ability to train; an unstable planning and training environment will also emerge—one that that will be at the mercy of weather that is extreme, unpredictable and dangerous.

Adverse environmental effects will not be limited to the ADF’s better-known training areas. Bare bases, including Curtin and Scherger, and training areas near Katherine, will also be unusable for substantial periods. Joint and combined exercises conducted from these locations will face the prospect of cancellation or rescheduling, while exercises using the Shoalwater Bay Training Area will experience the immediate devastation of adverse weather and may also suffer disruption through coastal erosion, with obvious effects on capability and mobilisation readiness. The resultant diminution in individual and collective skills and proficiency will compromise Army’s capability until the deficiency can be remediated under more favourable weather conditions. These effects will be felt across almost all capabilities—for example, infantry minor tactics will be constrained to benign and controlled barracks environments, and drivers will be unable to exercise on varying and complex terrain. In addition, flying opportunities for drone operators will be impaired and limited; the range of locations and opportunities for amphibious landing will narrow; Army will experience dust exposure during equipment maintenance and repair, including technical equipment; there will be adverse flying conditions for rotary-wing medical evacuation; and there will be increased risk to field supplies, including fuel. The list goes on.

Training System Disruption

With training areas less available, there will be inevitable consequences for the individual training system and the training continuum itself. Progressive training with substantial outdoor-based training objectives (such as officer training at the Royal Military College, Duntroon; and combat corps initial employment training) will require suspension and rescheduling. If this cannot be achieved before the notional graduation/march-out date, then Army will face the prospect of graduating officers and soldiers who have not completed the full suite of training outcomes. This will raise the spectre of Army having to deal with increased training deficiencies and backlogs. Shorter courses, such as some skills and promotion courses, will not be immune from the disruption and may face cancellation and rescheduling.

In the local unit environment, basic fitness assessments, combat fitness assessments, physical employment specification assessments and other readiness requirements will all face scheduling disruption. While these events require less planning and are simpler to reschedule than career and promotion courses, the condensed nature of many unit training programs will limit alternative opportunities for their conduct. The effects will be felt acutely in units with large proportions of service category 5 members,[34] who have limited parading opportunities. Additionally, members requiring reassessment, those returning from injury, or those who are unavailable on a scheduled event due to any of the myriad of life events, may not be able to achieve specific mandatory training outcomes in the timeframes normally specified. This situation may put at risk individual preparedness and eligibility for courses or promotion, and again, may compromise capability.

Career System Disruption

While climate-induced disruption to the conduct of courses and training will be problematic in itself, career managers will be confronted with the likely prospect of individuals not being fully qualified for posting or promotion when Army plans to post or promote them. While this issue is not foreign to career managers (who regularly face training deficiencies in their portfolios at an individual level), climate change disruption will result in entire cohorts who have not achieved the required criteria for posting or promotion.

Posting activities themselves will be disrupted by extreme weather events. Floods and extreme heat during the usual posting period of December/January, especially in locations such as Townsville, Ipswich or Darwin, are probable. This will have an obvious effect on those posting into and out of these locations, with a domino effect through the entire posting plot across the nation. Assuming that housing is not heavily affected by an extreme weather event (a large assumption), it could nevertheless take months for the posting plot and removals planning to recover, negatively influencing family schooling and spousal employment. If housing is affected, then the impact on individuals and their families, belongings and possessions will be substantial and may endure for lengthy periods. In these circumstances, the potential exists for negative mental health and wellbeing consequences to emerge for members and families. This topic is discussed further below.

With large portions of Army facing posting and promotion disruption, there will be a delay in the commencement of unit training programs, which will have an immediate effect on unit capability. This will include disruption to mission rehearsal exercises and certification. Further, where there is an ongoing overseas operation, disruption to force preparation, force generation, and rotation and redeployment cycles will occur. In some instances, unpopular short-notice extensions to deployments may be imposed, with the possibility that members will return to unit locations and to families dealing with the aftermath of a natural disaster in their absence.

Finally, not completing training, or not being promoted within an expected timeframe, will affect the placement of members on their respective trade pay scales. If courses are not conducted, or if specific training objectives cannot be met, individuals will not achieve the career progression milestones specified in the Manual of Army Employments for tier and grade advancement.[35] The consequences of being held back in training, promotion and salary are self-evident: not only would a member receive less salary, but also the impact on families, morale, and motivation may be irreconcilable for individuals who seek stability and career progression. Unless Army is able to develop some creative contingencies for climate change disruption, it will face pressure to reach a compromise on rigid longstanding progression policies. Measures in response may need to include climate-based retention contingencies.

Disruption to Families

It is not difficult to envisage the devastation that an extreme weather event will cause for families of military members, such as damage to homes and belongings. What are less obvious are the second-order effects. Suspension of schooling, damage to education facilities, or delays in arriving at a new schooling location will have an inevitable detrimental impact on children. Partners may experience greater difficulties in finding employment in an area affected by a weather event, or when they seek to transfer employment to a new location that has been affected. Housing availability will be reduced, which will result in limited options, increases in rental prices and/or dissatisfaction with defence housing. The Defence Member and Family Support agency and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs will need to provide more counselling and support services. Meanwhile, Defence will face increasing demand for services including access to emergency relief. While Defence has already demonstrated that it is able to respond and provide support in a limited capacity following isolated weather events, these services will need to be provided regularly, and at times concurrently, in different locations across Australia.

Retention Issues

So far this article has presented a bleak picture of the influence of climate change on training, career and family. For Army, perhaps the worst outcome is the potential repercussion regarding retention. Delayed or cancelled training opportunities, disrupted promotion and posting, and impacts on family may all culminate in negative sentiments towards Army, and members may respond by voluntarily separating from the military. Underlining all of these issues is the ongoing likelihood that Army will still be called on to support national disaster recovery efforts, despite recommendations in the DSR that this requirement is reduced or removed.[36] Individuals may find themselves serving in an Army that is struggling to adapt to climate change, and consumed by its consequences, rather than achieving the professional and personal outcomes they envisaged when they first joined.

Endnotes

[1] Albert Palazzo, ‘Climate Change and the Future Character of War’, Australian Army Journal 20, no. 1 (2024).

[2] ‘Understanding Climate Change’, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (website), at: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/policy/climate-science/understanding-climate-change (accessed 21 August 2024).

[3] Department of Defence, National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023), p. 41.

[4] Robert Glasser, ‘The ADF Will Have to Deal with the Consequences of Climate Change’, The Strategist, 28 April 2023, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-adf-will-have-to-deal-with-the-consequences-of-climate-change/. Glasser is optimistic that the choice of text was a product of bureaucratic editing rather than denial of the likelihood of climate impacts.

[5] Emma Storey, ‘“The great moral challenge”: The Ethics of Climate Change in the ADF’, The Forge, 18 November 2024, at: https://theforge.defence.gov.au/jamie-cullens-writing-competition-2024/great-moral-challenge-ethics-climate-change-adf.

[6] Elliot Parker, ‘Climate and Australia’s National Security’, The Forge, 16 November 2022, at: https://theforge.defence.gov.au/article/climate-and-australias-national-security.

[7] For example, Mike Copage, ‘Australia Should Work with NATO on Climate Change’, The Strategist, 10 July 2024, at: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australia-should-work-with-nato-on-climate-change/.

[8] Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, Food Fight: Climate Change, Food Crises & Regional Security (Canberra, June 2022), p. 4, at: https://www.aslcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ASLCG-Food-Fight-Report-June-2022-1.pdf.

[9] ‘Conflict and Climate’, United Nations Climate Change (website), 12 July 2022, at: https://unfccc.int/news/conflict-and-climate.

[10] ‘With Climate Crisis Generating Growing Threats to Global Peace, Security Council Must Ramp Up Efforts, Lessen Risk of Conflicts, Speakers Stress in Open Debate’, media release, United Nations (website), 13 June 2023, at: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15318.doc.htm.

[11] Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Implications of Climate Change for Australia’s National Security (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, May 2018), at: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Nationalsecurity/Final_Report.

[12] Ibid., p. 91.

[13] Amanda Gosling Clark, ‘Military Challenges from Climate Change’, Contemporary Issues in Air and Space Power 1, no. 1 (2023), at: https://ciasp.scholasticahq.com/article/88984-military-challenges-from-climate-change.

[14] Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, Too Hot to Handle: The Scorching Reality of Australia’s Climate-Security Failure (Canberra, May 2024), p. 1, at: https://www.aslcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ASLCG_TooHotTooHandle_2024R.pdf.

[15] Palazzo, ‘Climate Change and the Future Character of War’.

[16] Michael Evans, ‘Crutzen versus Clausewitz: The Debate on Climate Change and the Future of War’, Australian Journal of Defence and Strategic Studies 3, Number 1 (2021), at: https://www.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/research-publication/2021/AJDSS-v3-n1-interactive.pdf.

[17] Australian Security Leaders Climate Group (website), at: https://www.aslcg.org/ (accessed 21 August 2024).

[18] ‘Climate and Security Policy Centre’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute (website), at: https://www.aspi.org.au/program/climate-and-security-policy-centre (accessed 21 August 2024).

[19] Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, Too Hot to Handle, p. 4; and Jake Evans, ‘Climate Risks Ignored in National Defence Strategy, Former Defence Chief Says’, ABC News, 1 May 2024, at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-02/national-defence-strategy-ignored-climate-risks/103789018.

[20] Peter Aldhous, ‘Where Will Climate Change Hit Hardest? These Interactive Maps Offer a Telltale Glimpse’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (website), 28 February 2024, at: https://www.pnas.org/post/multimedia/interactive-climate-change-interactive-maps-offer-telltale-glimpse.

[21] At this temperature the work-to-rest ratio often becomes less than 50/50 (in scenarios involving heavy work), which is a ratio that may be untenable for both effective outdoor training and the conduct of operations by regional force surveillance units.

[22] Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, Too Hot to Handle, pp. 18–19.

[23] ‘Climate Heat Map of Australia’, Climate Council (website), at: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/heatmap/ (accessed 21 August 2024).

[24] In a world warmed by 3°C above the average temperature from 1850 to 1900. Aldhous, ‘Where Will Climate Change Hit Hardest?, ‘Deadly Heat and Humidity’ map.

[25] ‘Days above 32°C (90°F)’ (map), Probable Futures (website), at: https://probablefutures.org/maps/ (accessed 23 August 2024).

[26] Aldhous, ‘Where Will Climate Change Hit Hardest?’, ‘Devastating Droughts’ map.

[27] Palazzo, ‘Climate Change and the Future Character of War’.

[28] Aldhous, ‘Where Will Climate Change Hit Hardest?’.

[29] Phoenix Resilience, Feb–Mar 2022 Ipswich Flood Review (Ipswich City Council, 2022), p. 8, at: https://ipswich.infocouncil.biz/Open/2022/11/ESC_20221129_AGN_3103_AT_SUP_ExternalAttachments/ESC_20221129_AGN_3103_AT_SUP_Attachment_15104_1.PDF.

[30] National Emergency Management Agency, ‘Storms and floods, 2019: Queensland, January–February 2019’, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (website), at: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/2019-storms-and-floods-qld-townsville/.

[31] National Emergency Management Agency, ‘Storm—Severe Flooding from (Ex) Tropical Cyclone Tiffany: South Australia, 21 January – 3 February 2022’, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (website), at: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/flood-severe-flooding-from-ex-tropical-cyclone-tiffany-south-australia-2022/.

[32] Defence Housing Australia’, Defence Housing Australia Annual Report 2021–22 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2022), ‘Case Study—Supporting ADF Members during Emergencies’, at: https://www.transparency.gov.au/publications/defence/defence-housing-australia/defence-housing-australia-annual-report-2021-22/part-1---year-in-review/case-study---supporting-adf-members-during-emergencies.

[33] Australian Army, ArmySafe Manual, ‘S3BC4—Prevention and Management of Heat Casualties’, pp. 336–378, (internal document, 22 February 2022).

[34] Service Category 5 members, previously active reservists, are members who render effective service in ‘an enduring pattern of service’. See ‘ADF Pay and Conditions: ADF Total Workforce System’, Department of Defence (website), at: https://pay-conditions.defence.gov.au/adf-total-workforce-system.

[35] Australian Army, Manual of Army Employments (internal document).

[36] Defence Strategic Review, paras 5.3. to 5.5 and recommendations on p. 42.