The Australian Army’s current organisational structure is reminiscent of the fable of the rally driver who would not change his Cooper S Mini after he gave up racing and married. When the rally driver’s first child arrived, he retained the Mini as the family car on the assumption that he would eventually return to racing. A second child soon followed and the family could barely fit in the car. Yet the rally driver refused to dispose of his beloved racing vehicle. A third child duly arrived and the family found that it could not fit in the car at all. In order to resolve this dilemma, the rally driver, rather than recognise that he had the wrong car, insisted on undertaking two trips whenever it was necessary to transport his family.

Like the rally driver, the Australian Army also has ‘the wrong car’ and must change its approach to military organisation if it is to be an efficient 21st-century land force. With considerable investment in modern equipment and the important advances that the Hardening and Networking the Army initiative will bring, the land force cannot afford to retain an organisational structure that is designed for 20th-century, industrial-style armed conflict. Without significant and wide-ranging organisational reform, the emerging 21st-century Australian Army risks being squeezed into roles and situations for which it is neither designed nor suited.

Organisational redesign to meet the needs of future conflict is an imprecise art, but it is clear that the Army needs to develop an adaptable and agile structure over the next two decades. Such a structure would be capable of taking maximum advantage of emerging technologies while remaining true to the human character of war. The longer the Army delays change to its base organisation, the more obsolescent that organisation will gradually become.

Although predicting the future of war is an exercise fraught with difficulty, intellectual effort must be expended on it. In the 1990s, advocates of the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) argued in favour of a future conflict environment dominated by information technologies that recalled the spirit of Jomini rather than Clausewitz. Their approach was one of narrow science, without always considering the fundamental uncertainty at the heart of war as a basic human activity. However, one of the nuggets of great interest that emerged from RMA-style speculation was the concept of minimum-mass tactics. In broad terms, advocates of minimum-mass tactics argue that the age of the mass military formation has ended because detection and surveillance technologies have greatly enhanced the use of small teams of soldiers. In the future battlespace, small teams are likely to be capable of operating within a powerful information-technology network, which will permit greater situational awareness, decision superiority and tactical discretion in operations.

Early arguments in favour of minimum-mass tactics were, however, often exaggerated. For example, there was an unjustified belief that stand-off air strike would ameliorate the problem of close combat by land forces. This was an approach to combat that ran contrary to the entire history of warfare waged by armies, and one that has been exposed in the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2001. Nonetheless, although often exaggerated in its utility, the concept of minimum mass remains worthy of intellectual exploration within the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the Army particularly since it holds promise in the key area of future organisational design. The caveat is that the concept of minimum-mass tactics must not be removed from the context of realistic ground-combat conditions and must be seen within the contours of joint warfighting.

The Rise and Fall of Mass in Warfare

The adoption of minimum-mass tactics is not an argument for or against the use of advanced military technology. Rather, the concept of minimum mass is related to exploiting the physics of the modern battlespace. Mass may be defined as the ability to concentrate combat power at the decisive place and time. A salient lesson from military history from ancient to industrial warfare was that the combatant fielding the larger forces often won battles, campaigns and wars. As Napoleon once put it, victory usually went to the big battalions. A dominant theme in modern military history, particularly after warfighting became industrialised in the late 19th century, was the drive to outnumber and overwhelm an opponent with larger armies and bigger fleets. In World War II, quantity tended to overcome quality, particularly on the Eastern Front between 1943 and 1945 when the German and Soviet armies became locked in a war of mass and materiel.

Modern warfare, especially in the era of the two world wars between 1914 and 1945 was ultimately about a clash of industrial and materiel resources. During the Cold War from 1947 until 1989, mass continued to matter.

Indeed, until the coming of precision weapons in the late 1970s, it was the size of the Soviet and Warsaw Pact armies that convinced many Western observers in NATO that a Soviet-led mass attack on Western Europe could only be stopped by recourse to tactical nuclear weapons.

Since the late 20th century, the concentration on mass has declined principally for four reasons. First, in the wake of the end of the Cold War, the conventional power and high technology of the US military is largely unmatched by any other modern military. The 20th-century trend of matching symmetrical strength on the battlefield has been reversed, and gradually asymmetrical strategies such as insurgency, guerrilla warfare and terrorism have received more attention in military circles. In modern conflict characterised by the spectrum of peace, crisis and war, there are often no convenient targets for mass fires. Rather, civilians, aid agencies, refugees and combatants are frequently intertwined in an operational area.

This type of situation demands great discrimination in the use of force. Second, technological advances have made smaller weapon systems such as precision-guided missiles significantly more lethal. Most contemporary weapon systems possess sophisticated fire-control systems that enhance accuracy and destructive impact. In World War II, it took the Allied air forces 1000 bomber raids to destroy German cities. Today, precision firepower and Tomahawk cruise missiles are capable of demolishing selected urban targets with great accuracy. Hub-to-hub artillery pieces are being replaced by a variety of accurate weapons capable of precise applications of fire. In short, in the early 21st century, technological advances have made it no longer necessary to mass firepower in order to achieve tactical effects, as was the case during the era of the world wars in the 20th century.

Third, in an age of instant media images and electronic reporting, mass fires that produce mass effects—including large numbers of civilian casualties—are no longer acceptable or sustainable. Discrimination in targeting and restraint in inflicting destruction are required, and armies have become as concerned with how they fight as much as who they fight. The problems of collateral damage inflicted on both innocent civilians and their vital urban infrastructure have become areas of legitimate and pressing concern. Low-yield precise engagements are required far more often than mass saturation strikes. Modern armies cannot employ mass fires in an age in which the rehabilitation of an enemy and the reconstruction of his resources may be required as political imperatives.

Finally, in contemporary social conditions, armed forces are expensive to build and maintain. In particular, mass conscript armies have become not only unnecessary but also unaffordable. In post-industrial conditions, there has been a return to the small and highly trained professional forces that were the hallmark of pre-industrial limited warfare in 18th-century Europe, as practised by Frederick the Great of Prussia. Contemporary armies seek to become more highly trained and professional and in post-industrial societies must compete for scarce, high-quality manpower. In sum, the age of the great standing army supplied by conscripts as citizens in arms has passed. Small, professional armies are the norm in most of the modern West.

The combination of the above four factors raises serious questions about the value of relying on mass organisation in warfare. Mass has become a receding requirement and is losing its utility in an age when precision technology, low demography and postmodern social conditions call for a more discriminating and skilful form of warfare. The trend away from maximum numbers and indiscriminate firepower ushers in the possibility of, and indeed the need for, the adoption of realistic minimum-mass tactics.

Towards Minimum-Mass Tactics

Minimum-mass tactics may be defined as the use of multiple small teams in the battlespace, each capable of producing military effect both alone and in combination. Such tactical teams are characterised by a low electronic signature yet continue to possess an exponential combined-arms capability for battlespace effectiveness. Teams executing minimum-mass tactics require access to disengaged joint fires both from within and outside the battlespace.

The Importance of Small Signature

Since mass is gradually becoming redundant in military operations, teams engaged in minimum-mass tactics need to be small in order to survive detection in the electronic battlespace. Small teams have the advantage of emitting a low electronic signature while retaining combat agility. In modern combat conditions it is easier to hide and move a platoon rather than a battalion. It is also more effective to concentrate scarce military resources into smaller combat groups rather than larger, perhaps unwieldy, field formations.

Of course, there are some military contingencies—such as peace enforcement and urban operations—that continue to require relatively large numbers of troops to be deployed. It is arguable, however, that contemporary peace operations involve multiple government and non-government agencies as well as police. As a result, fewer troops may be required in the future. Similarly, the adage that urban operations require large numbers of infantry may be exaggerated. Urban operations require not infantry so much as multiple and effective combined-arms teams. The trend in both peacekeeping and urban operations now tends to be downwards, away from large numbers of troops.

Survivability and Single Effects

One of the problems in viewing minimum-mass tactics within the context of the RMA school of thought has been the fallibility of information networks. In a digital battlespace, highly networked teams are envisaged as sharing continuous battlespace awareness, thereby becoming capable of avoiding uncertainty and surprise. Yet a presumed ability to conduct operations through an immaculate battlespace overlooks the continued reality of fog and friction in warfare. Fog and friction might be reduced by technology but they can never be eliminated. Small-team operations using minimum-mass tactics must be able to survive the degradation or collapse of an electronic network. The best method of achieving this ability is by ensuring that each deployed team possesses an organic combined-arms capability for both mounted and dismounted combat. Each small-unit team must ultimately be capable of generating its own singular set of combat effects.

Networked Warfare and Combined Effects

While minimum-mass combat teams must be capable of executing singular effects, the combination of networked teams in the field remains the most effective way of applying combat power. Although networks are fallible, a network-centric or network-enabled approach to warfare exploits the tremendous advances in information volume and exchange that are now available to modern militaries. A networked force has great operational potential, and the employment of minimum-mass tactics assumes that a network approach enhances the combined effects of deployed teams. Such combined effects may be achieved by modular teams sharing situational awareness in order to speed their reaction times, by greater tactical agility in transitioning from task to task and by a greater capacity to call for indirect fires.

Decision Superiority and Professional Excellence

In their training, minimum-mass combat teams require an emphasis on perfecting small-team skills, and the ability to operate singularly. The adage should be ‘the network makes me better, but I do not rely on it. I can still achieve my task by myself when necessary’. Such a decentralised tactical approach requires an emphasis on achieving decision superiority through the combination of advanced combat skills, high small-unit morale and good leadership. The minimum-mass team requires guidance but not control from a network-centric approach to warfare. Acting semi-autonomously in the field, the aim should be for the small team to self-synchronise alongside other teams in order to meet different battlespace situations that might arise.

Special Forces and the Use of Minimum-Mass Tactics

Many military observers would argue that Australian Special Forces teams have already perfected the minimum-mass tactics described in this article. It is certainly true that small Special Forces teams epitomise the concept of small-unit warfare through the massing of effects rather than numbers. The question that arises is: should more of the Australian Army become Special Forces in character? This approach is not practical as a base structure for a modern land force. Military success cannot be achieved solely by the use of small, covert teams calling in disengaged fires. The Army continues to require a capacity for all arms warfare, and in this context minimum-mass tactics teams might operate using some Special Forces techniques but should retain a capability for heavier combat.

The only non–Special Force teams in the Army that have come close to adopting a minimum-mass tactical concept are cavalry units, whose troops often operate as miniature combined-arms teams. Australian cavalry have become used to operating independently with adaptability and agility. Cavalry units have, however, tended to be under-resourced, particularly in the vital and complementary area of dismounted warfare. Nonetheless, while mounted forces have often been either under-utilised or misemployed on operations, they represent a useful example of incipient minimum-mass tactical teams.

Towards Adopting Minimum-Mass Tactical Teams in the Australian Army

How should an ideal minimum-mass tactical team be composed? In the first place, such a team needs to be small yet still retain a capacity for combined arms action, including both dismounted and mounted warfare. A team’s approach to dismounted warfare needs to include the ability to patrol on foot and to close with and kill or capture the enemy. The team also requires the capability to remove physical obstacles, protect vehicles and conduct tactical surveillance.

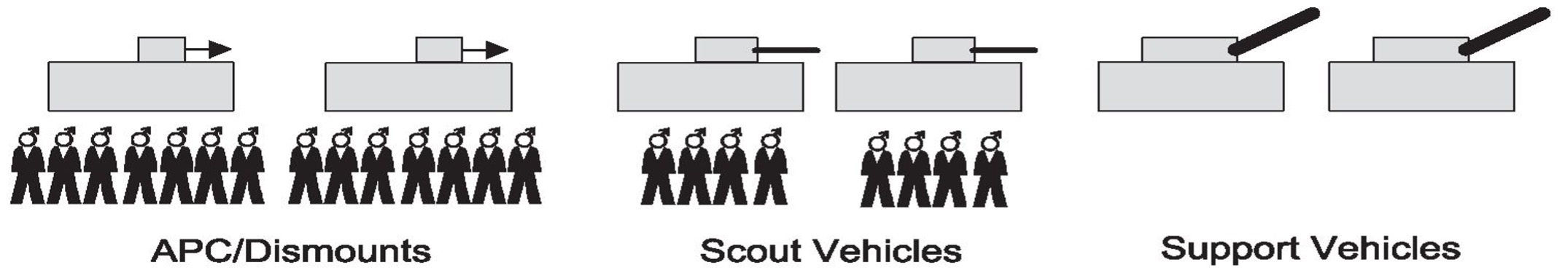

An effective minimum-mass tactical team needs armoured personnel carriers (APCs), armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) and scout vehicles. A pair of APCs would transport between six and eight dismounted soldiers in each vehicle. A pair of AFVs mounting cannon in order to destroy enemy vehicles, and neutralise bunkers and other entrenchments would be another essential component in any minimum-mass tactical team. An AFV should be protected against attack by enemy hand-held weapons, so permitting the vehicle to support dismounted troops in close fighting.

A minimum-mass tactical team based on two APCS, two AFVs and sixteen dismounted soldiers might be further enhanced by the inclusion of two lighter scout vehicles. A pair of scout vehicles armed with cannon and capable of carrying up to four soldiers adds flexibility and a reconnaissance capability to a tactical team.

In essence, then, the APCs with dismounted soldiers provide the minimum-mass teams with an infantry and scout capability; the scout vehicles would provide a cavalry and engineer capability; and the AFVs provide a tank and artillery effect. A minimummass team of six vehicles might be split into two three-vehicle patrols (one of each type of vehicle) in order to cover a wider area of territory. Such a six-vehicle team would have access to the electronic network and be able to upload and download data as required. The team vehicles would also have the ability to designate, compute and adjust disengaged fires from other teams or joint forces deployed in the field.

In the battlespace, future minimum-mass tactical teams will require headquarters and support elements. However, these need to be as small as possible and be located away from the battlespace, ideally on a sea base or on another sanctuary. Relevant aviation assets—including air lift capability and UAV reconnaissance—might be based away from the battlespace and be called forward only when required. Aviation would provide deep fires beyond the capability of the minimum-mass tactical teams. As there are no separate artillery units envisaged, the minimum-mass teams need to provide their own indirect fires or call for disengaged fires from joint assets, either air or naval. Moreover, the teams will be unsupported by separate field engineer units and must provide their own mobility and counter-mobility support. There are unlikely to be any separate vehicle-only armoured units, with all minimum-mass teams permanently grouped as mounted and dismounted combat teams.

The Modus Operandi of Minimum-Mass Tactical Teams

In warfighting operations, minimum-mass tactical teams can be deployed into a battlespace employing a version of ‘swarm’ tactics. Each tactical team can operate semi-independently, but remain close enough to each other in order to give mutual support through indirect fires and reinforcement. However, all teams would seek to avoid becoming a concentrated target by prevention of an established detectable pattern to a specific operation. The various tactical teams supported by aviation elements might superimpose their firepower over that of the ground units, or conduct independent operations in secondary sectors.

Figure 1. A Minimum-mass tactical Team

On contact with the enemy, team scout vehicles might attempt to use on-board sensors to designate targets for aviation fire support and other elements capable of providing disengaged fires. Dismounted soldiers and AFVs would in response try to close with and to defeat fixed adversaries. A minimum-mass tactical team outclassed in an engagement with an enemy force might seek to call for fires from other teams and call to be reinforced. In complex terrain, the various tactical teams need to possess sufficient combined-arms capability in order to operate without additional support.

In stability operations, minimum-mass tactical teams support other agencies through ‘presence patrolling’ and by establishing route and static defence of key communication nodes. Since members of the team patrol either mounted or dismounted, it is possible to adapt a force posture as required. Given the integral mobility of the teams, they can be task-organised for specific missions and be transported by air to their objectives.

The Australian Army and Minimum-Mass Tactics

Acceptance of a minimum-mass tactical approach within the Army will require a conscious movement beyond our present industrial-age corps organisation. The Army cannot continue to try to mould an industrial-age force structure into a postindustrial security environment. While it is necessary to retain the traditional functions of infantry, artillery, engineers and armour, these force elements need to be grouped not at battalion level but at a lower level, preferably that of minimum-mass tactical teams. The adoption of minimum-mass tactical organisation is not about an increase in soldier numbers, but rather is concerned with the most efficient use of troops. The number of battalions required should be replaced by a calculation based on how many minimum-mass teams the land force is capable of fielding.

If, in the future, the Army does not permanently organise its combat power into tactical teams, then the need will be to compensate for this deficiency by a focus on combined training and by emphasising professional development in training courses and officer training. If, for instance, the Army tried to splice together a minimum-mass team structure from current equipment, scout vehicles might have to be drawn from ASLAVs along with engineers, and APCs for the infantry. However, no infantry or engineer unit is currently mounted in ASLAV. The AFVs or support vehicles might be tanks, but the latter currently lack an indirect-fire capability. In terms of artillery, towed guns would, in minimum-mass conditions, have to be left behind. Moreover, self-propelled guns mounted on trucks lack the ability to close with and support the infantry. The Army’s bewildering array of different corps, vehicles, mobility and gun calibres means a long support train that conflicts with training requirements.

The Army needs to develop a team capability from scratch. Training and logistics need to become operations-led and serve the needs of the fighting soldier. There are considerable efficiencies in training if the land force was to prepare soldiers on the basis of a single building-block to train the entire Army, rather than cater for the peculiar requirements of each corps.

A transformed 21st-century Army involves the following six features. First, there should be a continued Special Forces organisation, but with 4 RAR concentrating less on company-level operations and far more on small-team operations. Second, the land force would benefit from an expanded cavalry regimental capability in order to create true minimum-mass teams. Such an approach requires the adequate provision of dismounted troops and mortars in order to conform to doctrinal requirements. Manpower and direct fire for dismounted troops might be drawn from reorganised infantry and artillery units. Ultimately, expanded and reinforced cavalry units might form the Army’s standard minimummass teams.

Third, armoured and mechanised infantry units can be reorganised into minimum-mass teams, with additional dismounted troops possibly drawn from engineer formations. In the future, armoured and mechanised formations, supplemented by current and future equipment, can form ‘heavy’ minimum-mass teams. A fourth measure is to develop light infantry, artillery and engineering elements into either Special Force–style formations or into ‘light’ minimum-mass teams that retain combined arms functions. Fifth, the Army’s aviation elements might reorganise themselves into a functional air–ground minimum-mass formation. Finally, the Army’s construction engineer capability could be expanded in order to support stability operations.

Conclusion

The Australian Army is currently organised for the last war, not the next. We need to appreciate that we do not require mass forces in the future and that our tactical organisation is designed for an obsolescent form of warfare, namely industrial-age warfare based on numbers of soldiers. Ultimately, the number of battalions we have is irrelevant if those battalions are organised incorrectly or are regularly broken up in order to meet the contingencies of real-world operations. The Army of the future must organise from the bottom up, structuring itself along minimum-mass lines in order to create an effective base-fighting element. The land force requires an available combined-arms capability at all times and it needs to train in expectation of likely combat conditions. Such an approach means that the Army needs to ‘organise as it will fight’.

The Australian Army has always held the belief that its small-unit teams are the foundation on which its professional reputation has been built. The fine performance of our individual soldiers and small teams in East Timor, Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere continues to justify this belief. Let us then build on the small-unit foundation as the basis of a 21st-century army and ensure that effective military teams employing minimum-mass tactics provide the way of the future.